Abstract

The mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) regulate a variety of cellular processes. The three main MAPK cascades are the extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38 kinases. A typical MAPK cascade is composed of MAP3K-MAP2K-MAPK kinases that are held by scaffold proteins. Scaffolds function to assemble the protein tier and contribute to the specificity and efficacy of signal transmission. WD repeat domain 62 (WDR62) is a JNK scaffold protein, interacting with JNK, MKK7, and several MAP3Ks. The loss of WDR62 in human leads to microcephaly and pachygyria. Yet the role of WDR62 in cellular function is not fully studied. We used the CRISPR/Cas9 and short hairpin RNA approaches to establish a human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 with WDR62 loss of function and studied the consequence to JNK signaling. In growing cells, WDR62 is responsible for the basal expression of c-Jun. In stressed cells, WDR62 specifically mediates TNFα−dependent JNK activation through the association with both the adaptor protein, TNF receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2), and the MAP3K protein, mixed lineage kinase 3. TNFα-dependent JNK activation is mediated by WDR62 in HCT116 and HeLa cell lines as well. MDA-MB-231 WDR62-knockout cells display increased resistance to TNFα−induced cell death. Collectively, WDR62 coordinates the TNFα receptor signaling pathway to JNK activation through association with multiple kinases and the adaptor protein TRAF2.

INTRODUCTION

The mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) regulate a variety of cellular processes by transmission of extracellular signals to changes of gene expression in the nucleus. In a typical MAPK cascade, a hierarchal activation includes MAP3K, MAP2K, and MAPK proteins (Cargnello and Roux, 2011). The three main groups of MAPKs are the extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs), stress-activated protein kinases (SAPKs, also known as c-Jun N-terminal kinases, JNKs), and p38 kinases (Chen and Tan, 2000). A case in point is the JNK signaling pathway, for which several MAP3Ks have been described to activate the two MAP2Ks, MKK4 and MKK7, which activate the three isoforms of JNK 1–3. JNK1 and JNK2 are expressed ubiquitously, whereas JNK3 is expressed primarily in neuronal tissues, testes, and cardiomyocytes (Bode and Dong, 2007). The JNK pathway is activated by various stimuli, including inflammatory cytokines, heat shock, oxidative stress, osmotic stress, and UV irradiation (Ip and Davis, 1998). Once activated, JNK phosphorylates a variety of proteins on specific serine and threonine residues that are immediately followed by a proline residue, resulting in the regulation of diverse cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation, survival, and apoptosis (Bogoyevitch and Kobe, 2006). JNK has a dual role in the balance between proliferation and apoptosis, and the outcome of JNK activation depends on cellular context and the specific stimulus (Vleugel et al., 2006). The JNK signaling pathway is implicated in many pathophysiological conditions, such as cancer (Wagner and Nebreda, 2009), diabetes (Aguirre et al., 2000), autoimmune diseases (Schett et al., 2000; Roy et al., 2008), and neurodegenerative diseases (Borsello and Forloni, 2007). This makes JNK a therapeutic target for several diseases (Manning and Davis, 2003; Bogoyevitch, 2005; Yarza et al., 2015). However, given the complexity of the JNK signaling network and the fact that JNK functions in many different signaling events, direct inhibition of JNK may have serious adverse complications and side effects (Bubici and Papa, 2014). Therefore, a better understanding of specific JNK signaling pathway is required to design novel therapeutic targets.

A group of proteins that contribute to JNK specificity and signal efficacy are the scaffold proteins. These proteins are defined as molecules that are able to associate with at least two components of the MAPK tier. Scaffold proteins are relatively large platforms that assemble the proteins required for a specific pathway in the right place and in a timely manner (Shaw and Filbert, 2009). Several scaffold proteins have been described for the JNK pathway, including JNK interacting proteins (JIPs) (Whitmarsh, 2006), β-arrestin-2 (McDonald et al., 2000), Filamin (Marti et al., 1997), and JNK1-associated membrane protein (Kadoya et al., 2005). Previously, using the Ras recruitment system (Broder et al., 1998), we identified a novel JNK scaffold protein, WD repeat domain 62 (WDR62) (Wasserman et al., 2010). WDR62 associates with JNK, MKK7, and several MAP3Ks, such as mixed lineage kinase 2 (MLK2), mixed lineage kinase 3 (MLK3), sterile alpha motif and leucine zipper containing kinase AZK alpha (ZAKα), delta-like homologue 1 (DLK1), and transforming growth factor beta-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) (Wasserman et al., 2010; Cohen-Katsenelson et al., 2011, 2013; Hadad et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016), and therefore is considered a bona fide JNK-scaffold protein. However, the precise physiological role of WDR62 under normal and stress conditions is not completely understood. During interphase, WDR62 is predominantly localized in the cytoplasm, and it translocates to the spindle pole during mitosis (Nicholas et al., 2010). Interestingly, recessive mutations in WDR62 are associated with severe malformations in brain development such as microcephaly and pachygyria (Bilguvar et al., 2010; Nicholas et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2010). In WDR62 knockout mice, neural progenitor cells (NPCs) showed spindle instability, mitotic arrest, and cell death (Chen et al., 2014). In contrast, WDR62 perturbation had a much milder effect in nonneuronal cell lines such as HeLa. HeLa cells with WDR62 knockdown displayed a slight delay in mitotic progression. The duration of mitosis was prolonged, and some spindle orientation and integrity defects were observed (Bogoyevitch et al., 2012). However, cell proliferation and cell viability were not altered in these experiments, indicating a limited role for WDR62 in cell-cycle progression in nonneuronal tissues (Bogoyevitch et al., 2012). This is consistent with the fact that human patients with recessive mutation in WDR62 exhibit normal growth of all tissues except for the brain.

In this study, we examined the role of WDR62 in cellular signaling. The CRISPR/Cas9 and short hairpin RNA (shRNA) approaches were used to establish a human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 with either WDR62-knockout (WDR62-KO) or WDR62 knockdown (WDR62-KD) and to study the consequences in JNK signaling. We show that WDR62 specifically mediates tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα)-dependent JNK activation through association with TNF receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2) and MLK3.

RESULTS

Generation of MDA-MB-231 WDR62-KO cells

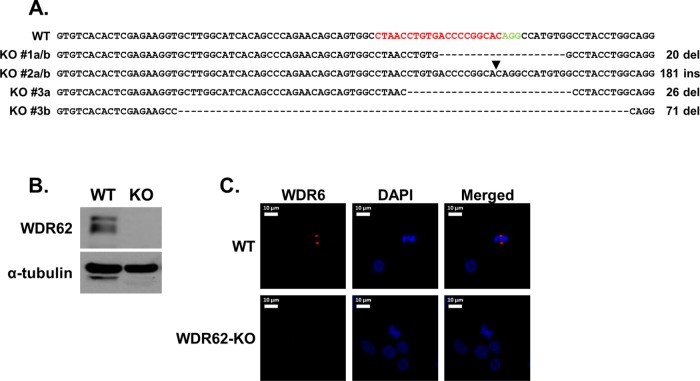

To generate MDA-MB-231 WDR62-KO cells, we employed the CRISPR/Cas9 approach using WDR62-specific guide RNA (gRNA) (Figure 1A) as described under Materials and Methods. Three KO-positive clones were identified, while one clone was initially characterized in more detail. Successful ablation of WDR62 expression was examined by Western blot, and frameshift mutation was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Figure 1, A and B). In addition, wild-type (WT) and WDR62-KO MDA-MB-231 cells were fixed and stained with antibody against WDR62. While the WT cells exhibited the expected pattern of WDR62 localization in the centrosomes of dividing cells, no staining was detected in the centrosomes of WDR62-KO dividing cells (Figure 1C). We next sought to examine how loss of WDR62 affects cell cycle, proliferation, and viability in MDA-MB-231 cells. Cell cycle analysis showed no difference in the cell distribution along the cell cycle between WT and WDR62-KO cells (Supplemental Figure 1, A and B). Similarly, no difference was observed in cell proliferation (Supplemental Figure 1C) or basal apoptosis rate (Supplemental Figure 1D) between WT and WDR62-KO cells.

FIGURE 1:

Generation of MDA-MB-231 WDR62-KO cells. (A) Sequence of exon 2 of WT WDR62 and three clones with WDR62-KO. The sequences a and b in each clone represents the two mutated alleles. The gRNA sequence that was used is shown in red and the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) is shown in green. Hyphens indicate deleted nucleotides; arrowhead indicates site of insertion. Clone #1 was selected for further characterization. (B) Western blot analysis of WDR62-KO clone #1 cells. WT and WDR62-KO MDA-MB-231 were immunoblotted using WDR62 antibody. The expression level of α-tubulin served as loading control. (C) WDR62 expression in MDA-MB-231 WT and WDR62-KO dividing cells: Cells were fixed and stained with anti-WDR62 polyclonal antibody (red) and DAPI (blue). Representative images of dividing cells are shown.

JNK activation in WT and WDR62-KO cells

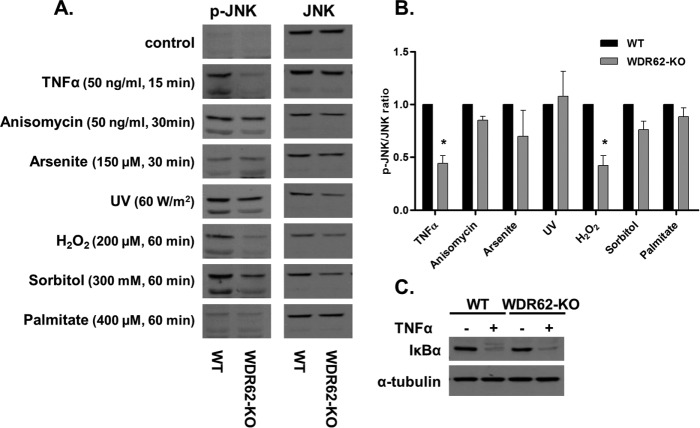

Next, we examined how WDR62 deficiency affects JNK activation in response to various stimuli. Wild-type and WDR62-KO cells were treated with known JNK-activating agents as indicated. Following treatments, cells were harvested, and whole-cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by Western blotting using phospho-JNK and total JNK antibodies (Figure 2). All treatments resulted in efficient JNK activation. The extent of JNK activation was similar in WT and WDR62-KO following treatment with anisomycin, arsenite, UV irradiation, osmotic stress, and palmitate. In contrast, JNK activity was strongly suppressed in WDR62-KO cells following treatment with TNFα and hydrogen peroxide as compared with WT cells. Thus, WDR62 expression is specifically required to link TNFα and hydrogen peroxide with JNK activation but not other stimuli. In a previous study, it was demonstrated that hydrogen peroxide–dependent JNK activation is mediated by the TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1) (Pantano et al., 2003). Thus, we decided to focus our study on TNFα signaling. The TNFR1 is known to activate simultaneously two signaling pathways: the JNK-AP-1 axis and the IKK-NFκB axis. To reveal whether WDR62-KO affected the latter as well, we examined IκBα degradation using Western blot analysis. In contrast to the reduced JNK activation in WDR62-KO cells, there was no difference in IκBα degradation following TNFα treatment (Figure 2C). Thus, we concluded that the loss of WDR62 expression affected the JNK-AP-1 axis specifically without affecting the TNFR-dependent IKK-NFκB signaling pathway.

FIGURE 2:

JNK activation in WT and WDR62-KO cells. (A) WT and WDR62-KO MDA-MB-231 cells were exposed to various stimuli as indicated. Following stimulation, cells were harvested and lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-phospho-JNK antibody. Total JNK antibody served as reference. (B) Densitometric quantification of the Western blot analysis shown in A. The ratio of p-JNK/JNK obtained with WT cells was determined as 1 while the ratio obtained with WDR62-KO was determined relatively. Data are expressed as mean ratio ± SEM from three independent experiments. *p ≤ 0.05. (C) WT and WDR62-KO cells were treated with TNFα (50 ng/ml) for 15 min. IκBα expression level was examined by Western blot. The expression level of α-tubulin served as loading control.

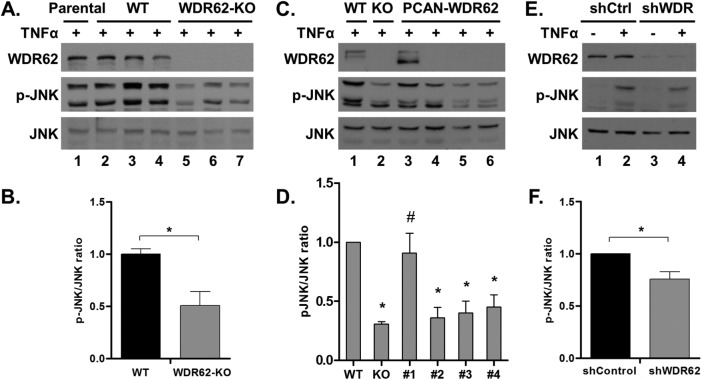

To rule out the possibility of CRISPR-related off-target effects or clonal heterogeneity, we repeated the TNFα experiment with the two additional WDR62-KO clones and compared them to three WT clones. JNK activation following TNFα treatment was significantly reduced in all three WDR62-KO clones as compared with WT cells counterparts (Figure 3, A and B). To further support the fact that WDR62 deficiency is responsible for suboptimal JNK activation by TNFα, WDR62 expression was reintroduced in WDR62-KO MDA-MB-231 cells. Toward this end, WDR62-KO cells were stably transfected with WDR62 expression plasmid. Cells were selected by G418, and since the overall expression of WDR62 in the transfected cells was very low (unpublished data), single-cell clones were isolated by limited dilution. We identified one clone with WDR62 expression similar to the parental cells. WT cells, WDR62-KO cells, this clone, and three other clones negative for WDR62 expression were treated with TNFα. JNK activation was fully restored in the WDR62-positive clone but not in the WDR62-negative clones (Figure 3, C and D). To strengthen the results obtained with the CRISPR/Cas9 derived WDR62-KO cells, we used a shRNA approach to knock down WDR62 expression. MDA-MB-231 cells were infected with either shControl or shWDR62 lentiviruses, followed by selection with puromycin. The extent of JNK activation in response to TNFα treatment was evaluated. Consistently, WDR62-KD MDA-MB-231 cells displayed a significant reduction in JNK activation following TNFα treatment (Figure 3, E and F). The difference in JNK activation was milder as compared with the CRISPR/Cas9 KO approach, which is expected due to the incomplete ablation of WDR62 expression using the shRNA approach (Figure 3, E and F). Collectively, the data suggest a significant role for WDR62 in mediating TNFα-dependent JNK activation in MDA-MB-231 cells.

FIGURE 3:

Validation of WDR62 role in TNFα signaling. (A, B) Parental MDA-MB-231 cells, three WT clones, and three WDR62-KO clones were treated with TNFα (50 ng/ml) for 15 min. Following stimulation, cells were harvested and subjected to Western blot and densitometric analysis with p-JNK and JNK antibodies. Results are expressed as the mean ratio ± SEM of the three clones from each group. *p ≤ 0.05 compared with WT cells. (C, D) WDR62-KO cells were stably transfected with empty vector or WDR62 expression plasmids. One WDR62-positive clone and three WDR62-negative clones were treated with TNFα (50 ng/ml) for 15 min and subjected to Western blot and densitometric analysis. WT and WDR62-KO cells were used as controls. *p ≤ 0.05 compared with WT, #p ≤ 0.05 compared with WDR62-KO cells. (E,F) MDA-MB-231 cells were infected with shControl or shWDR62 lentiviruses. Cells were treated with TNFα (50 ng/ml) for 15 min and subjected to Western blot and densitometric analysis. *p ≤ 0.05 compared with shControl cells. The ratio of p-JNK/JNK obtained with TNFα-treated WT cells was determined as 1 while the ratio obtained with other TNFα-treated cells was determined relatively to their appropriate WT control. Results are expressed as the mean ratio ± SEM of three to five independent experiments.

To generalize the finding that WDR62 mediates TNFα-dependent JNK activation, we tested the effect of WDR62 deficiency in two additional cell lines. To this end, we used the CRISPR/Cas9 approach to generate WDR62-KO in HCT116 (human colon cancer) and in HeLa cells (human cervical cancer). Three independent WDR62-KO clones as well as WT clones were isolated from each cell line. WDR62 deficiency was confirmed by Sanger sequencing and Western blotting analysis (Supplemental Figure 2, A and B, and Figure 3, A and B). Next, we examined the extent of JNK activation following TNFα treatment. JNK activation was significantly higher in the WT clones as compared with the WDR62 deficient clones in both HCT116 and HeLa cell lines (Supplemental Figures 2, B and C, and 3, B and C).

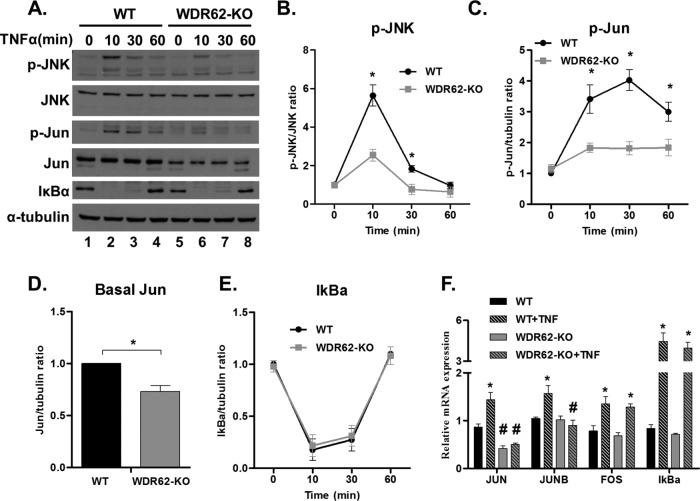

We next sought to examine the kinetics of TNFα induced JNK activation. Toward this end, WT and WDR62-KO MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with TNFα, and cell lysates were prepared at different times as indicated (Figure 4, A and B). This experiment revealed that JNK activation was significantly reduced in WDR62-KO cells during the first 30 min following TNFα stimulation. In addition, WDR62-KO cells failed to effectively phosphorylate c-Jun, the major JNK substrate (Figure 4, A and C). Interestingly, total c-Jun levels were lower in WDR62-KO unstimulated cells (Figure 4D). This could be due to chronic down-regulation of the JNK signaling pathway. As expected, there was no difference in IκBα degradation and recovery during all time points between WT and WDR62-KO cells (Figure 4E). To reveal the mode of regulation of c-Jun expression levels, we performed quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) on cDNA derived from mRNA of TNFα-treated cells (Figure 4F). Indeed, c-Jun and JunB, which are known JNK targets (Bogoyevitch and Kobe, 2006), were up-regulated following TNFα treatment in WT cells but not in WDR62-KO cells. This is consistent with the c-Jun expression levels shown by Western blot analysis (Figure 4, A and D). In contrast, c-Fos and IκBα transcription was up-regulated similarly following TNFα treatment (Figure 4F). The transcription of these genes is regulated by the ERK signaling pathway (Whitmarsh, 2007) and the IKK-NFκB axis (Scott et al., 1993), respectively. Collectively, WDR62 expression is responsible for the maintenance of c-Jun basal expression levels and the induction of c-Jun and JunB transcription following TNFα treatment.

FIGURE 4:

Time course of TNFα-induced JNK activation. (A–E) WT and WDR62-KO cells were treated with TNFα (50 ng/ml) for the indicated time points. Following stimulation, cells were harvested and subjected to Western blot analysis and densitometric analysis with the indicated antibodies. p-JNK level is expressed relative to total JNK (B); p-Jun, c-Jun, and IκBα levels are expressed relative to α-tubulin (C–E). The ratio of p-JNK/JNK, p-Jun/α-tubulin, c-Jun/α-tubulin, and IκBα/α-tubulin obtained with untreated WT cells was determined as 1, while the ratio obtained with all other samples was determined relatively. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *p ≤ 0.05 comparing between WT and WDR62-KO counterparts. (F) WT and WDR62-KO cells were treated with TNFα (50 ng/ml) for 30 min. Then, mRNA was extracted and the indicated genes were analyzed by qRT-PCR. The expression level of GAPDH gene was used to normalization. Results are expressed as the mean ratio ± SEM of three independent experiments. *p ≤ 0.05 comparing treated to untreated cells of the same genotype; #p ≤ 0.05 comparing between WT and WDR62-KO counterparts.

Interaction of WDR62 with key component of TNFα signaling

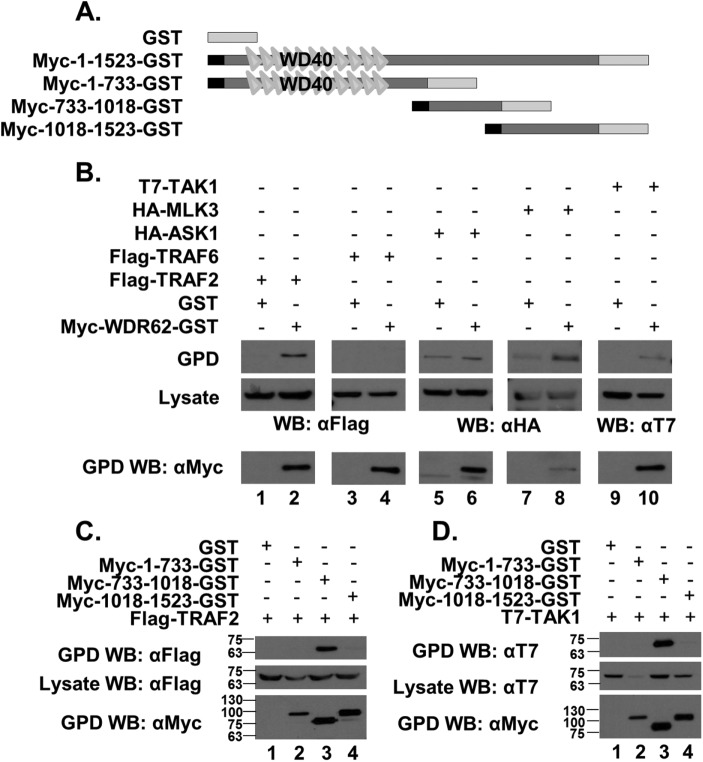

We next sought to reveal the mechanism by which WDR62 mediates TNFα-induced JNK activation. TNF receptor-associated factors (TRAFs) are adaptor proteins that couple the TNF receptor family to signaling pathways. TRAF2 plays a key role in JNK activation following stimulation with TNFα (Liu et al., 1996). To test whether WDR62 interacts with TRAF proteins, we cotransfected human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK-293) T cells with plasmids encoding GST or GST fused to WDR62 together with plasmids encoding either FLAG-TRAF2 or FLAG-TRAF6, which is another adaptor protein from the TRAF family (Xie, 2013). Twenty-four hours following transfection, cell lysates were prepared and subsequently incubated with glutathione-coated beads followed by extensive washes. Eluted proteins were resolved by SDS–PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting. Flag-TRAF2 efficiently precipitated with WDR62-GST but not with GST protein alone (Figure 5B, lanes 1 and 2). In contrast, no precipitated Flag-TRAF6 was observed with either GST or WDR62-GST (Figure 5B, lanes 3 and 4)

FIGURE 5:

Interaction of WDR62 with key component of TNFα signaling. (A) Schematic representation of the WDR62 fragments used in this experiment. The black square represents the Myc epitope-tag and the light-gray rectangle represents the GST tag. (B–D) HEK-293T cells were cotransfected with expression plasmids as indicated. Cell lysates were pulled down with glutathione beads, and eluted proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE, followed by Western blot with the appropriate antibodies as indicated. The expression level of transfected plasmids was determined by blotting the total cell lysate with the appropriate antibodies.

Identifying the potential MAP3K mediating WDR62 TNFα-dependent JNK activation

Previously, we have shown that WDR62 interacts with JNK, MKK7, and several MAP3K, including MLK3 (Wasserman et al., 2010; Cohen-Katsenelson et al., 2011, 2013; Hadad et al., 2015). Mainly three kinases have been described as putative MAP3Ks of the TNFα-induced JNK cascade: MLK3 (Brancho et al., 2005), apoptosis signal regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) (Nishitoh et al., 1998), and TAK1 (Shim et al., 2005). To examine which of these MAP3Ks mediate TNFα-related JNK activation via WDR62, we performed a GST pull-down assay using GST-tagged WDR62 together with HA-ASK1, HA-MLK3, or T7-TAK1. HA-MLK3 and T7-TAK1 proteins were efficiently precipitated specifically with WDR62-GST and not with GST protein. In contrast, no interaction was observed with HA-ASK1 protein (Figure 5B).

Previously we mapped MLK3 interaction with WDR62 to two association domains within WDR62, corresponding to amino acids 733–971 and amino acids 1031–1212 (Hadad et al., 2015). We next mapped the domain within WDR62 that interacts with TRAF2 and TAK1. To map TAK1 and TRAF2 association domains within WDR62, we performed the GST pull-down assay as above, with different GST-fused fragments of WDR62 (Figure 5A). Both TRAF2 (Figure 5C) and TAK1 (Figure 5D) were precipitated efficiently with the WDR62 fragment corresponding to 733–1018 amino acids. In contrast, TRAF2 and TAK1 did not interact with the WDR62 1018–1523 fragment that was previously shown to interact with MLK3 (Hadad et al., 2015). Collectively, the 733–1018 domain was shown to associate with the MAP3Ks; TAK1 and MLK3 and the TNFR1 adaptor protein TRAF2.

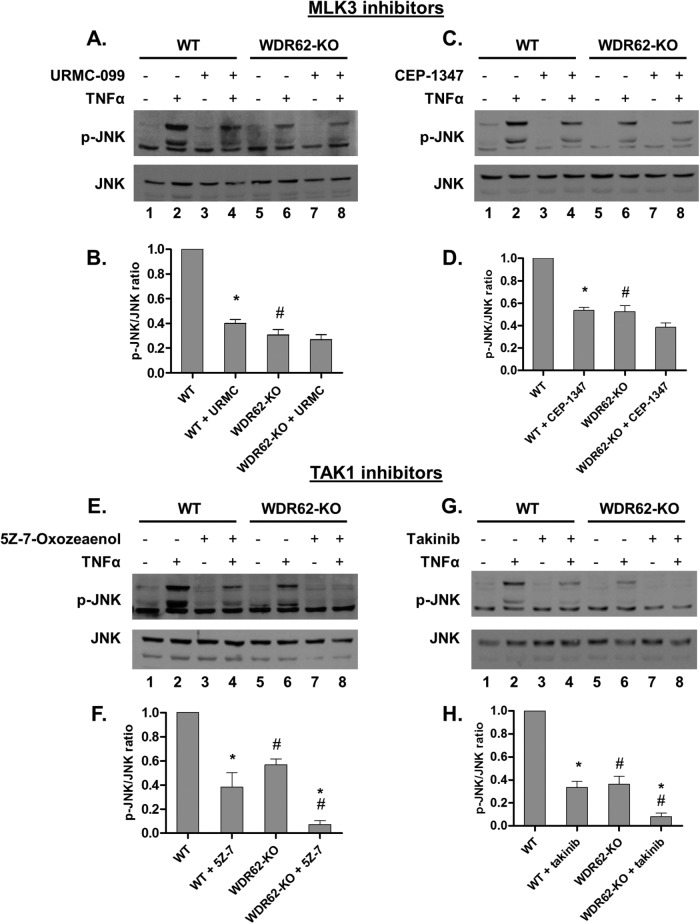

WDR62 mediates TNFα-induced JNK activation through MLK3

Next, we sought to determine whether WDR62 mediates TNFα-induced JNK activation through MLK3 or TAK1. Toward this end, we inhibited MLK3 using the specific inhibitors URMC-099 or CEP-1347, while TAK1 was inhibited using the specific inhibitors 5z-7-Oxozeaenol or takinib. We used concentrations of inhibitors sufficient to attenuate TNFα-induced JNK activation in MDA-MB-231 WT cells to the levels of WDR62-KO. Inhibitors were added to the medium 1 h prior to stimulation with TNFα (Figure 6). In WT cells, JNK activation following TNFα treatment was significantly lower following pretreatment with each of the four inhibitors used. In WDR62-KO cells, inhibition with both of the TAK1 inhibitors resulted in complete ablation of JNK activation. In contrast, MLK3 inhibitors had only a marginal effect on JNK activity in WDR62-KO cells following TNFα treatment. Collectively, these results suggest that WDR62 mediates TNFα-dependent JNK activation through MLK3.

FIGURE 6:

WDR62 mediates TNFα-induced JNK activation through MLK3. (A–D) WT and WDR62-KO cells were preincubated with the selective MLK3 inhibitors URMC-099 (100 nM) or CEP-1347 (50 nM) for 1 h and then treated with TNFα (50 ng/ml) for 15 min. (E–H) WT and WDR62-KO cells were preincubated with the selective TAK1 inhibitors 5Z-7-Oxozeaenol (20 nM) or takinib (2 µM) for 1 h then treated with TNFα (50 ng/ml) for 15 min. JNK activation was determined by Western blotting and densitometric analysis with p-JNK and JNK antibodies. The ratio of p-JNK/JNK obtained with TNFα-only treated WT cells was determined as 1 while the ratio obtained with all other treatments was determined relatively. Results are expressed as the mean ratio ± SEM of three independent experiments. *p ≤ 0.05, comparing pretreated to not pretreated cells of the same genotype; #p ≤ 0.05, comparing between WT and WDR62-KO counterparts.

Interaction of MLK3 and TRAF2 is independent of WDR62

TRAF2-MLK3 interaction is required for efficient TNFα-induced MLK3 activation (Sondarva et al., 2010). Since WDR62 interacts with both TRAF2 and MLK3, we were interested to study whether WDR62 mediates the association between TRAF2 and MLK3. To this end, we cotransfected HEK-293T with plasmids encoding HA-MLK3, Flag-TRAF2, and Myc-WDR62 as indicated in Supplemental Figure 4, followed by immunoprecipitation with the appropriate antibodies. TRAF2 was precipitated efficiently with MLK3 in the absence of WDR62 (Supplemental Figure 4A). Similarly, MLK3 was precipitated efficiently with TRAF2 in the absence of WDR62 (Supplemental Figure 4B), indicating that WDR62 does not directly mediate the association of MLK3 with TRAF2 but rather directs this association to JNK activation.

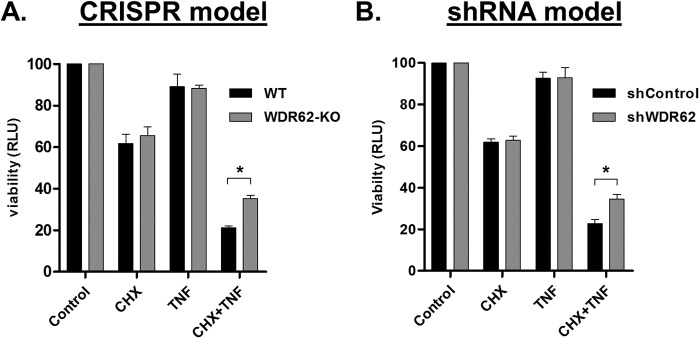

WDR62 mediates TNFα-induced apoptosis

One of the most studied aspects of TNFα is its ability to induce apoptosis depending on the cell tested. In most cell lines including MDA-MB-231, induction of TNFα-induced apoptosis requires inhibition of the anti-apoptotic NFκB pathway, usually by using translational inhibitors such as cycloheximide (CHX). JNK inhibitor, SP600125, has been shown to confer resistance to such induction of apoptosis, suggesting a proapoptotic role for JNK in TNFα-induced apoptosis (Won et al., 2010). To examine the role of WDR62 in this pathway, WT and WDR62-KO cells were treated with CHX and TNFα, and cell viability was determined. WDR62-KO cells were significantly more resistant to cotreatment with TNFα and CHX in comparison to WT cells (Figure 7A). Similar results were obtained with shWDR62-infected cells (Figure 7B). Collectively, WDR62 mediates TNFα-dependent apoptosis through activation of the proapoptotic JNK axis.

FIGURE 7:

WDR62-deficient cells are less sensitive to TNFα-induced apoptosis. (A) MDA-MB-231 WT and WDR62-KO cells; (B) MDA-MB-231 shRNA control and WDR62-KD cells were treated with CHX (10 µg/ml) and TNFα (50 ng/ml) for 24 h. Viability was assayed with CellTiter-Glo reagent. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. The viability obtained with control untreated cells was determined as 100, while the viability obtained with all other treatments was determined relatively. Results are expressed as the mean relative light unit (RLU) ± SEM of three independent experiments. *p ≤ 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Scaffold proteins are important functional components that contribute to signal specificity and efficacy (Shaw and Filbert, 2009). WDR62 is a JNK scaffold protein, interacting with JNK, MKK7 and several MAP3Ks (Wasserman et al., 2010; Cohen-Katsenelson et al., 2011, 2013; Hadad et al., 2015). The loss of WDR62 in neural progenitor cells results in cell death and reduced proliferation (Chen et al., 2014) leading to microcephaly and pachygyria (Bilguvar et al., 2010; Nicholas et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2010). Yet, the role of WDR62 in nonneuronal tissues was not determined. Here, we established MDA-MB-231 cells with WDR62-KO and studied how WDR62 loss affects cell growth and JNK signaling. Previously, it was shown that WDR62 knockdown in HeLa cells did not alter cell proliferation and viability (Bogoyevitch et al., 2012). In contrast, suppression of WDR62 promoted apoptosis and inhibited cell growth of gastric cancer cells by inducing cell-cycle arrest (Zeng et al., 2013). Our data in MDA-MB-231 cells show that WDR62 deficiency does not affect proliferation or cell-cycle distribution.

In MDA-MB-231 cell line, WDR62 deficiency dampened JNK activation following TNFα and hydrogen peroxide treatment, but did not result in reduced JNK activation following other stress inducers. TNFα treatment also induced lower JNK activation in HCT116 and HeLa cells that are WDR62-deficient. Interestingly, the expression level of c-Jun was lower in unstimulated MDA-MB-231 WDR62-KO cells as compared with WT cells. This might be due to lower basal JNK activity in WDR62-KO cells that are below the detection levels by standard methods. Alternatively, we cannot exclude the possibility that WDR62 affects gene expression in JNK-independent manner.

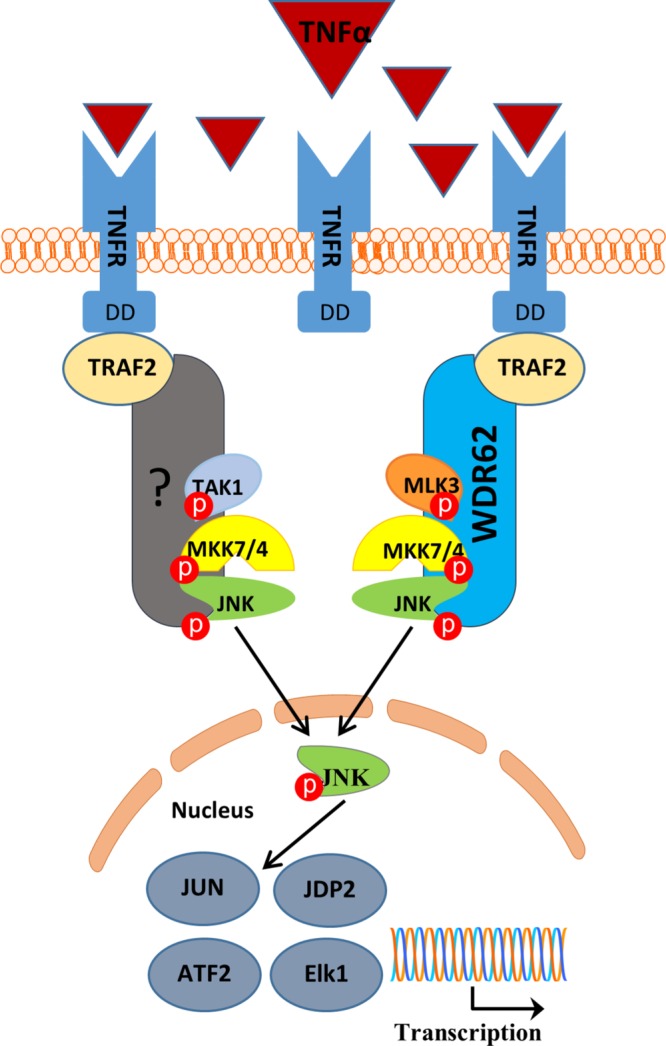

Upon binding of TNFα to the TNFR1, activation of caspase 8 promotes apoptosis while induction of the NFκB pathway leads to cell survival (Aggarwal, 2003). In addition, JNK activity is pro-apoptotic in the context of TNFα stimulation (Dhanasekaran and Reddy, 2008; Won et al., 2010). We demonstrate that the reduced response of WDR62-KO cells to TNFα is specific to the JNK pathway, but not to NFκB, and this results in reduced sensitivity to TNFα induced apoptosis. In previous studies, ASK1, TAK1 and MLK3 have been implicated in TNFα-related activation of JNK (Nishitoh et al., 1998; Brancho et al., 2005; Shim et al., 2005). We show that WDR62 may interact with both TAK1 and MLK3, but only the interaction with MLK3 is essential for JNK activation by TNFα. Our results are consistent with a previous study demonstrating that MLK3 deficiency in mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) causes selective reduction of TNFα-dependent JNK activation without affecting the NFκB pathway following TNFα treatment or JNK activation following other stimuli (Brancho et al., 2005).

Here we showed that WDR62 is connecting TNFR1 to JNK signaling specifically through TRAF2 but not TRAF6. TRAF6 participates in the activation of the IL-1R/JNK pathway (Wu and Arron, 2003). TRAF2 is an adaptor protein with a putative role in mediating the JNK pathway following stimulation with TNFα (Liu et al., 1996). Interestingly, both WDR62 and TRAF2 are localized to stress granules upon cellular stresses (Kim et al., 2005; Wasserman et al., 2010). Interaction of TRAF2 with MLK3 is essential for TNFα-induced activation of MLK3 and JNK (Sondarva et al., 2010). We mapped the interaction site of TRAF2 to amino acids 733-1018 domain of WDR62. TAK1 (Figure 5D) and MLK3 (Hadad et al., 2015) also showed interaction with this domain. It is not clear from our study whether all these interactions occur simultaneously or represent direct individual association with WDR62. Alternatively, a large protein complex can be formed through the association with a third protein yet to be identified. Overexpression of WDR62 did not affect association of MLK3 with TRAF2. MLK3 associates with WDR62 possibly through two domains therefore the formation of a tertiary complex is plausible. More experiments are required to reveal the precise mechanism by which WDR62 mediates the association of TRAF2-MLK3 with JNK activation.

This is the first study demonstrating the association of WDR62 scaffold protein with an adaptor protein that directly links the activation of the JNK signaling pathway to receptor activation. Interestingly, Filamin was also shown to connect the TNFR1 with the JNK signaling tier (Marti et al., 1997). It would be interesting to reveal the association of WDR62 with other adaptors proteins that connect JNK to additional cytokines and growth factor receptors. The association of adaptors with scaffold proteins becomes a common theme in signal transduction, for example in T-cells, GADS adaptor protein associates with additional adaptors such as Grb2 and SLP76 to link T-cell receptor signaling to various cell fates (Lugassy et al., 2015).

TNFα is an inflammatory cytokine that has been implicated in many human diseases such as diabetes (Hotamisligil and Spiegelman, 1994) and cancer (Balkwill, 2009). Progression of these diseases is related to chronic inflammation and it was suggested that TNFα has an important role in this link. JNK is a major signaling pathway that is activated by TNFα (Aggarwal, 2003). JNK activation by TNFα contributes to the molecular events that promote the pathophysiological conditions. For example, activation of JNK in insulin target tissues leads to serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 resulting in suppression of the insulin signaling (Hirosumi et al., 2002). In cancer, JNK activation promotes the proliferation, invasion and migration of tumor cells (Wagner and Nebreda, 2009). We demonstrated that WDR62 protein plays a role in JNK-dependent activation by TNFα and thus can serve as a new therapeutic target to uncouple the TNFα-JNK axis. The main reported function of TNFα in cell culture is to induce cell death, and indeed WDR62 depletion resulted in relative resistance to TNFα-induced apoptosis. However, more research in animal models needs to be performed in order to reveal the full potential of WDR62 as a regulator of the TNFα/MLK3/JNK pathway.

Collectively, this study suggests that WDR62 mediates part of TNFα-induced JNK activation through coordination of TRAF2/MLK3/MKK7/JNK (Figure 8). Another scaffold protein yet to be identified may be involved in mediating JNK activation specifically through TAK1. WDR62 does not participate in NFκB activation following TNFα or JNK activation following other stimuli. WDR62-KO cells display reduced activation of the proapoptotic pathway JNK and thus show increased resistance to TNFα-induced apoptosis.

FIGURE 8:

Schematic model for WDR62-mediated TNFα-dependent JNK activation. Following TNFα binding to TNF receptor, WDR62 recruits MLK3, MKK7, and JNK to TRAF2, allowing efficient activation of JNK by TNFα. Another scaffold protein mediating the TRAF2/TAK1/JNK axis is yet to be determined. Red circles represent phosphorylation.

MATERIALs AND METHODS

Reagents

The following reagents were used in our study: collagen (Roche, Indianapolis, IN; 11179179001), G418 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), recombinant human TNFα (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ; 300-01A), anisomycin (Fermentek, Jerusalem, Israel; AN), arsenite (Fluka, Ronkonkoma, NY; 71287). Sorbitol (S1876), sodium palmitate (P9767), puromycin (P7255), 5Z-7-Oxozeaenol (O9890), and cycloheximide (C7698) were all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). URMC-099 was purchased from AdooQ BioScience LLC (Irvine, CA; A14219). Takinib was purchased from MedChemExpress (Monmouth Junction, NJ; HY-103490). CEP-1347 was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK; 4924).

Antibodies

The following primary antibodies were used: anti-phospho-JNK polyclonal (Sigma-Aldrich; J4644), anti-JNK polyclonal (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA; #9252), and anti-JNK monoclonal (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; sc-7345). The polyclonal anti-JNK antibody was used in Figures 2A, 3, A and E, 4A, and 6, A and E. In these figures, p-JNK and JNK levels were assayed in duplicate blots. The monoclonal anti-JNK antibody was used in Figures 3C and 6, C and G, Supplemental Figure 2B, and Supplemental Figure 3B. In these figures, p-JNK and JNK levels were studied sequentially using the same blot. The following were also used: anti-α-tubulin monoclonal (Sigma-Aldrich; T9026), anti-c-Jun polyclonal (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; SC-1694), anti-phospho-c-Jun polyclonal (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; SC-822), anti IκBα (c21) polyclonal (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; SC-371), anti-Myc monoclonal (clone 9E10; Abcam), anti-HA monoclonal (clone 12CA5; Abcam), anti-Flag (M2) monoclonal (Sigma-Aldrich; F1804), and anti-T7 polyclonal (Abcam; ab9115). Anti-WDR62 (JBP5) polyclonal antibody was produced in our own laboratory, as described previously (Wasserman et al., 2010).

Plasmids

A 20-base-pair gRNA sequence (Figure 1A) targeting exon 2 of WDR62 was cloned into pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP(PX458) (Addgene plasmid #48138) according to the protocol of the Zhang laboratory (Broad Institute of Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University, Cambridge, MA) (Ran et al., 2013) to obtain pSpCas9-GFP-WDR62. WDR62 fragments fused to myc and glutathione S-transferase (GST) were cloned into the mammalian expression plasmid pcDNA3-AIRAP-GST-V3 (Stanhill et al., 2006) by replacing the AIRAP fragment with myc-tagged WDR62 fragments. The mammalian expression plasmid pcDNA 3XHA was used to express HA-MLK3 and HA-ASK1. The mammalian expression vector pCAN was used to express Myc-WDR62. The expression plasmids encoding for T7-TAK1 and HA-ASK1 were kindly provided by Alan Whitmarsh (Division of Molecular and Cellular Function, University of Manchester, UK). FLAG-TRAF2 and FLAG-TRAF6 were a kind gift from Ito Michihiko (Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kitasato University, Japan) and were previously described (Yasuda et al., 1999; Yamaguchi et al., 2009).

Cell culture and transfections

MDA-MB-231, HCT116, HeLa, and human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK-293T) cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 0.1 µg/ml streptomycin and grown at 37°C and 5% CO2. HEK-293T cells were transfected with the appropriate expression plasmids using the calcium phosphate method (Batard et al., 2001). The total amount of plasmid DNA was adjusted to 12 μg in a total volume of 1 ml. Cell culture medium was replaced with fresh medium 4–5 h posttransfection, and cells were harvested 24 h thereafter. MDA-MB-231, HCT116, and HeLa cells were transfected using lipofectamin 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA; 11668027) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To produce stable WDR62 expression in MDA-MB-231 WDR62-KO cells, G418 (800 µg/ml) was added to the medium 24 h following transfection for 4 wk. Single-cell clones of G418-resistant cells were isolated by limited dilution in 96-well plates. WDR62 expression of expanded colonies was determined by Western blot.

Generation of WDR62-KO cells

MDA-MB-231, HCT116, and HeLa cells were cotransfected with pSpCas9-GFP-WDR62 and pBabe-puro-myc. An empty pSpCas9-GFP vector was similarly transfected as a negative control. Following 24 h from transfection, cells were selected in the presence of puromycin (2 µg/ml) for 48 h. Single-cells clones of puromycin-resistant cells were isolated by limited dilution in 96-well plates. WDR62 expression of expanded colonies was measured by Western blot. Clones showing complete loss of WDR62 were further confirmed by Sanger sequencing of exon 2 of WDR62. The negative control puromycin-resistant cells were pooled and used as WT control.

Lentivirus production and generation of stable WDR62-KD MDA-MB-231 cells

WDR62-KD in MDA-MB-231 cells was obtained by infection with shRNA lentiviruses. MISSION shRNA specific for WDR62 was used (Sigma Aldrich; TRCN0000243235), while the shControlA plasmid (Santa Cruz; SC-108060) was used as control. HEK-293T cells were cotransfected with shWDR62 or shControlA together with vesicular stomatitis virus G (VSV-G) and ΔNRF (encoding the gag and pol genes) plasmids. Lentivirus-containing medium from HEK-293T-transfected cells was used directly to infect MDA-MB-231 cells. Infected cells were selected with puromycin (2 µg/ml) for 1 wk.

Cellular treatments

To lower the basal JNK activity, cells were serum starved in 0.2% FCS medium for 16 h prior to all cellular treatment except for the viability assay following cotreatment with CHX and TNFα in which cells were treated in complete medium. UV-C irradiation was performed using an 8-W bulb at 30 cm distance for 1 min. A UV radiometer was used to measure the exposure to UV light. The medium was removed prior to irradiation and returned immediately thereafter for 30 min followed by cell harvesting. To measure cell viability following treatment, CellTiter Glo reagent (Promega; G7570) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blot

Cells were lysed in whole cell extract (WCE) buffer (25 mM HEPES at pH 7.7, 0.3 M NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 20 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 0.1 mM Na2VO4, 100 μg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], Protease inhibitor cocktail 1:100; Sigma Aldrich, P8340). The lysates were separated by 10% SDS–PAGE followed by transfer to nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat dry milk and then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Proteins were detected using the corresponding horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich; anti-rabbit A0545, anti-mouse A0168). Densitometric analysis was performed using TotalLab (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) software.

GST pull-down assay

Transfected HEK-293T cells were lysed in WCE buffer. Glutathione-agarose beads (Sigma-Aldrich; G4510) were precleared with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (wt/vol). Then the beads were incubated with 400–600 µg of the protein extract for 1 h at 4°C. The beads were washed with WCE buffer, and the precipitated proteins were eluted using freshly made glutathione elution buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 20 mM l-glutathione (Sigma-Aldrich; G4251), 1 mM DTT, and 1 mM PMSF. Samples were subjected to Western blot analysis. Total lysates shown represent 10% of the lysate used for GST pull down.

Coimmunoprecipitation

Transfected HEK-293T cells were lysed in WCE buffer. Protein lysates (400–600 µg) were precleared with nonrelevant antibodies followed by incubation with protein-A Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare,Piscataway, NJ; 17-0780-01). Then the lysates were incubated overnight at 4°C with the relevant antibodies, followed by incubation with protein-A Sepharose beads for 1 h. The beads were washed with WCE buffer and the precipitated protein were eluted using SDS–PAGE sample buffer and then subjected to Western blot.

Immunofluorescence

MDA-MB-231 cells were grown on glass cover slips coated with collagen. Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 10 min and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min. Following incubation in blocking solution of 5% FCS in phosphate-buffered serum (PBS) for 30 min, cells were incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies mixture in 1% FCS in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Following three washes, cells were incubated with secondary fluorescent antibodies mixture prepared in PBS containing 2% BSA, 2% FCS, and 0.1% Tween-20. The cells were washed and stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma-Aldrich, D9542). Stained cells were mounted in fluoromount-G (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL, 0100-01). Images were acquired with a Zeiss LSM 700 upright confocal microscope.

Cell-cycle analysis

MDA-MB-231 cells were detached and resuspended in PBS. Cells were fixed by slowly adding the suspension to 70% ethanol. Following incubation on ice for 20 min, the cells were centrifuged and resuspended in a mixture containing 40 µg/ml propidium iodide (Invitrogen; p3566) and 10 µg/ml RNase (Sigma-Aldrich; R6148) for 30 min. Stained cells were analyzed by BD LSRFortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Annexin-V/7-aad apoptosis analysis

MDA-MB-231 cells were detached and resuspended in an annexin-V binding buffer (10 mM HEPES at pH 7.4, 140 mM NaCl, and 2.5 mM CaCl2) containing annexin-V conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Biolegend) and 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) (Biolegend). Following 15-min incubation at RT in the dark, samples were analyzed by BD LSRFortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

mRNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR

mRNA was isolated from MDA-MB-231 cells using a High Pure RNA Isolation Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Manheim, Germany; 11828665001) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized from 400 ng of purified mRNA using a iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA; #170-8891). Real-time PCR was performed using Rotor-Gene 6000TM (Corbett) equipment with SYBR-green mix (Bio-Rad; #172-5124). Serial dilutions of a standard sample were included for each gene to generate a standard curve. Values were normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression levels. The following primers were used:

JUN F: CTGCAAAGATGGAAACGACCTT;

JUN R: TCAGGGTCATGCTCTGTTTCAG;

JUNB F: ACAAACTCCTGAAACCGAGCC;

JUNB R: CGAGCCCTGACCAGAAAAGTA;

FOS F: CACTCCAAGCGGAGACAGAC;

FOS R: AGGTCATCAGGGATCTTGCAG;

IκBα F: CCCCTACACCTTGCCTGTG;

IκBα R: CACGTGTGGCCATTGTAGTTG;

GAPDH F: ATGGGGAAGGTGAAGGTCG; and

GAPDH R: GGGGTCATTGATGGCAACAATA;

Statistical analysis

Comparison between two means was performed by two-tailed t test. Comparison between several means was performed by one-way analysis of variation (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis. Comparison between two genotypes in different time points was performed by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni posttest analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software (La Jolla, CA).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Edith Suss-Tuby and Amir Grau for cell imaging and flow cytometry analysis, respectively. We thank Alan Whitmarsh for providing HA-ASK1 and T7-TAK1 expression plasmids, Ito Michihiko for providing FLAG-TRAF2 and FLAG-TRAF6 expression plasmids, and the members of the Aronheim lab for valuable comments. This study was partially supported by Israel Science Foundation grant no. 573/11 to A.A.

Abbreviations used:

- ASK1

apoptosis signal regulating kinase 1

- HEK-293

human embryonic kidney 293

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MLK3

mixed lineage kinase 3

- TAK1

transforming growth factor beta-activated kinase 1

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor α

- TRAF2

TNF receptor-associated factor 2

- WDR62

WD repeat domain 62.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E17-08-0504) on August 9, 2018.

REFERENCES

- Aggarwal BB. (2003). Signalling pathways of the TNF superfamily: a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Immunol , 745–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre V, Uchida T, Yenush L, Davis R, White MF. (2000). The c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase promotes insulin resistance during association with insulin receptor substrate-1 and phosphorylation of Ser(307). J Biol Chem , 9047–9054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkwill F. (2009). Tumour necrosis factor and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer , 361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batard P, Jordan M, Wurm F. (2001). Transfer of high copy number plasmid into mammalian cells by calcium phosphate transfection. Gene , 61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilguvar K, Ozturk AK, Louvi A, Kwan KY, Choi M, Tatli B, Yalnizoglu D, Tuysuz B, Caglayan AO, Gokben S, et al. (2010). Whole-exome sequencing identifies recessive WDR62 mutations in severe brain malformations. Nature , 207–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode AM, Dong Z. (2007). The functional contrariety of JNK. Mol Carcinog , 591–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogoyevitch MA. (2005). Therapeutic promise of JNK ATP-noncompetitive inhibitors. Trends Mol Med , 232–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogoyevitch MA, Kobe B. (2006). Uses for JNK: the many and varied substrates of the c-Jun N-terminal kinases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev , 1061–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogoyevitch MA, Yeap YY, Qu Z, Ngoei KR, Yip YY, Zhao TT, Heng JI, Ng DC. (2012). WD40-repeat protein 62 is a JNK-phosphorylated spindle pole protein required for spindle maintenance and timely mitotic progression. J Cell Sci , 5096–5109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsello T, Forloni G. (2007). JNK signalling: a possible target to prevent neurodegeneration. Curr Pharm Des , 1875–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brancho D, Ventura JJ, Jaeschke A, Doran B, Flavell RA, Davis RJ. (2005). Role of MLK3 in the regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascades. Mol Cell Biol , 3670–3681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broder YC, Katz S, Aronheim A. (1998). The ras recruitment system, a novel approach to the study of protein-protein interactions. Curr Biol , 1121–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubici C, Papa S. (2014). JNK signalling in cancer: in need of new, smarter therapeutic targets. Br J Pharmacol , 24–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cargnello M, Roux PP. (2011). Activation and function of the MAPKs and their substrates, the MAPK-activated protein kinases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev , 50–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JF, Zhang Y, Wilde J, Hansen KC, Lai F, Niswander L. (2014). Microcephaly disease gene Wdr62 regulates mitotic progression of embryonic neural stem cells and brain size. Nat Commun , 3885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YR, Tan TH. (2000). The c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway and apoptotic signaling (review). Int J Oncol , 651–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Katsenelson K, Wasserman T, Darlyuk-Saadon I, Rabner A, Glaser F, Aronheim A. (2013). Identification and analysis of a novel dimerization domain shared by various members of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) scaffold proteins. J Biol Chem , 7294–7304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Katsenelson K, Wasserman T, Khateb S, Whitmarsh AJ, Aronheim A. (2011). Docking interactions of the JNK scaffold protein WDR62. Biochem J , 381–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanasekaran DN, Reddy EP. (2008). JNK signaling in apoptosis. Oncogene , 6245–6251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadad M, Aviram S, Darlyuk-Saadon I, Cohen-Katsenelson K, Whitmarsh AJ, Aronheim A. (2015). The association of the JNK scaffold protein, WDR62, with the mixed lineage kinase 3, MLK3. MAP Kinase , 5307. [Google Scholar]

- Hirosumi J, Tuncman G, Chang L, Gorgun CZ, Uysal KT, Maeda K, Karin M, Hotamisligil GS. (2002). A central role for JNK in obesity and insulin resistance. Nature , 333–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotamisligil GS, Spiegelman BM. (1994). Tumor necrosis factor alpha: a key component of the obesity-diabetes link. Diabetes , 1271–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip YT, Davis RJ. (1998). Signal transduction by the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)–from inflammation to development. Curr Opin Cell Biol , 205–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadoya T, Khurana A, Tcherpakov M, Bromberg KD, Didier C, Broday L, Asahara T, Bhoumik A, Ronai Z. (2005). JAMP, a Jun N-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1)-associated membrane protein, regulates duration of JNK activity. Mol Cell Biol , 8619–8630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WJ, Back SH, Kim V, Ryu I, Jang SK. (2005). Sequestration of TRAF2 into stress granules interrupts tumor necrosis factor signaling under stress conditions. Mol Cell Biol , 2450–2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZG, Hsu H, Goeddel DV, Karin M. (1996). Dissection of TNF receptor 1 effector functions: JNK activation is not linked to apoptosis while NF-kappaB activation prevents cell death. Cell , 565–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugassy J, Corso J, Beach D, Petrik T, Oellerich T, Urlaub H, Yablonski D. (2015). Modulation of TCR responsiveness by the Grb2-family adaptor, Gads. Cell Signal , 125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning AM, Davis RJ. (2003). Targeting JNK for therapeutic benefit: from junk to gold? Nat Rev Drug Discov , 554–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti A, Luo Z, Cunningham C, Ohta Y, Hartwig J, Stossel TP, Kyriakis JM, Avruch J. (1997). Actin-binding protein-280 binds the stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK) activator SEK-1 and is required for tumor necrosis factor-alpha activation of SAPK in melanoma cells. J Biol Chem , 2620–2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald PH, Chow CW, Miller WE, Laporte SA, Field ME, Lin FT, Davis RJ, Lefkowitz RJ. (2000). Beta-arrestin 2: a receptor-regulated MAPK scaffold for the activation of JNK3. Science , 1574–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas AK, Khurshid M, Desir J, Carvalho OP, Cox JJ, Thornton G, Kausar R, Ansar M, Ahmad W, Verloes A, et al. (2010). WDR62 is associated with the spindle pole and is mutated in human microcephaly. Nat Genet , 1010–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishitoh H, Saitoh M, Mochida Y, Takeda K, Nakano H, Rothe M, Miyazono K, Ichijo H. (1998). ASK1 is essential for JNK/SAPK activation by TRAF2. Mol Cell , 389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantano C, Shrivastava P, McElhinney B, Janssen-Heininger Y. (2003). Hydrogen peroxide signaling through tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 leads to selective activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J Biol Chem , 44091–44096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran FA, Hsu PD, Wright J, Agarwala V, Scott DA, Zhang F. (2013). Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Protoc , 2281–2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy PK, Rashid F, Bragg J, Ibdah JA. (2008). Role of the JNK signal transduction pathway in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol , 200–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schett G, Tohidast-Akrad M, Smolen JS, Schmid BJ, Steiner CW, Bitzan P, Zenz P, Redlich K, Xu Q, Steiner G. (2000). Activation, differential localization, and regulation of the stress-activated protein kinases, extracellular signal-regulated kinase, c-JUN N-terminal kinase, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, in synovial tissue and cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum , 2501–2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott ML, Fujita T, Liou HC, Nolan GP, Baltimore D. (1993). The p65 subunit of NF-kappa B regulates I kappa B by two distinct mechanisms. Genes Dev , 1266–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw AS, Filbert EL. (2009). Scaffold proteins and immune-cell signalling. Nat Rev Immunol , 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim JH, Xiao C, Paschal AE, Bailey ST, Rao P, Hayden MS, Lee KY, Bussey C, Steckel M, Tanaka N, et al. (2005). TAK1, but not TAB1 or TAB2, plays an essential role in multiple signaling pathways in vivo. Genes Dev , 2668–2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sondarva G, Kundu CN, Mehrotra S, Mishra R, Rangasamy V, Sathyanarayana P, Ray RS, Rana B, Rana A. (2010). TRAF2-MLK3 interaction is essential for TNF-alpha-induced MLK3 activation. Cell Res , 89–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanhill A, Haynes CM, Zhang Y, Min G, Steele MC, Kalinina J, Martinez E, Pickart CM, Kong XP, Ron D. (2006). An arsenite-inducible 19S regulatory particle-associated protein adapts proteasomes to proteotoxicity. Mol Cell , 875–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vleugel MM, Greijer AE, Bos R, van der Wall E, van Diest PJ. (2006). c-Jun activation is associated with proliferation and angiogenesis in invasive breast cancer. Hum Pathol , 668–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EF, Nebreda AR. (2009). Signal integration by JNK and p38 MAPK pathways in cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer , 537–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman T, Katsenelson K, Daniliuc S, Hasin T, Choder M, Aronheim A. (2010). A novel c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-binding protein WDR62 is recruited to stress granules and mediates a nonclassical JNK activation. Mol Biol Cell , 117–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmarsh AJ. (2006). The JIP family of MAPK scaffold proteins. Biochem Soc Trans , 828–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmarsh AJ. (2007). Regulation of gene transcription by mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta , 1285–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won M, Park KA, Byun HS, Sohn KC, Kim YR, Jeon J, Hong JH, Park J, Seok JH, Kim JM, et al. (2010). Novel anti-apoptotic mechanism of A20 through targeting ASK1 to suppress TNF-induced JNK activation. Cell Death Differ , 1830–1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Arron JR. (2003). TRAF6, a molecular bridge spanning adaptive immunity, innate immunity and osteoimmunology. Bioessays , 1096–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie P. (2013). TRAF molecules in cell signaling and in human diseases. J Mol Signal , 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi T, Miyashita C, Koyano S, Kanda H, Yoshioka K, Shiba T, Takamatsu N, Ito M. (2009). JNK-binding protein 1 regulates NF-kappaB activation through TRAF2 and TAK1. Cell Biol Int , 364–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarza R, Vela S, Solas M, Ramirez MJ. (2015). c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling as a therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease. Front Pharmacol , 321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda J, Whitmarsh AJ, Cavanagh J, Sharma M, Davis RJ. (1999). The JIP group of mitogen-activated protein kinase scaffold proteins. Mol Cell Biol , 7245–7254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu TW, Mochida GH, Tischfield DJ, Sgaier SK, Flores-Sarnat L, Sergi CM, Topcu M, McDonald MT, Barry BJ, Felie JM, et al. (2010). Mutations in WDR62, encoding a centrosome-associated protein, cause microcephaly with simplified gyri and abnormal cortical architecture. Nat Genet , 1015–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng S, Tao Y, Huang J, Zhang S, Shen L, Yang H, Pei H, Zhong M, Zhang G, Liu T, et al. (2013). WD40 repeat-containing 62 overexpression as a novel indicator of poor prognosis for human gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer , 3752–3762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Yu J, Yang T, Xu D, Chi Z, Xia Y, Xu Z. (2016). A novel c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling complex involved in neuronal migration during brain development. J Biol Chem , 11466–11475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.