Significance

Protected areas (PAs) are the cornerstone of conservation yet face funding inadequacies that undermine their effectiveness. Using the conservation needs of lions as a proxy for those of wildlife more generally, we compiled a dataset of funding in Africa’s PAs with lions and estimated a minimum target for conserving the species and managing PAs effectively. PAs with lions require $1.2 to $2.4 billion or $1,000 to $2,000/km2 annually, yet receive just $381 million or $200/km2 (median) annually. Nearly all PAs with lions are inadequately funded; deficits total $0.9 to $2.1 billion. Governments and donors must urgently and significantly invest in PAs to prevent further declines of lions and other wildlife and to capture the economic, social, and environmental benefits that healthy PAs can confer.

Keywords: budget, comanagement, conservation effectiveness, deficit, funding need

Abstract

Protected areas (PAs) play an important role in conserving biodiversity and providing ecosystem services, yet their effectiveness is undermined by funding shortfalls. Using lions (Panthera leo) as a proxy for PA health, we assessed available funding relative to budget requirements for PAs in Africa’s savannahs. We compiled a dataset of 2015 funding for 282 state-owned PAs with lions. We applied three methods to estimate the minimum funding required for effective conservation of lions, and calculated deficits. We estimated minimum required funding as $978/km2 per year based on the cost of effectively managing lions in nine reserves by the African Parks Network; $1,271/km2 based on modeled costs of managing lions at ≥50% carrying capacity across diverse conditions in 115 PAs; and $2,030/km2 based on Packer et al.’s [Packer et al. (2013) Ecol Lett 16:635–641] cost of managing lions in 22 unfenced PAs. PAs with lions require a total of $1.2 to $2.4 billion annually, or ∼$1,000 to 2,000/km2, yet received only $381 million annually, or a median of $200/km2. Ninety-six percent of range countries had funding deficits in at least one PA, with 88 to 94% of PAs with lions funded insufficiently. In funding-deficit PAs, available funding satisfied just 10 to 20% of PA requirements on average, and deficits total $0.9 to $2.1 billion. African governments and the international community need to increase the funding available for management by three to six times if PAs are to effectively conserve lions and other species and provide vital ecological and economic benefits to neighboring communities.

Protected areas (PAs) are the foundation of international efforts to secure biodiversity (1, 2). PAs play a critical role in conserving high-priority species, including the African lion (Panthera leo), one of the most iconic symbols of Africa and a proxy for ecological health (3, 4). At least 56% of lion range falls within PAs, and the species reaches its highest population densities in PAs with high prey densities and where lion populations are well-managed and protected from primary threats (3, 5). Shortfalls in funding, combined with mounting human pressures, have weakened the management capacity in most African PAs and contributed to rapid declines in numbers of lions, their prey, and other species (6–9). Lion numbers have decreased by 43% in just two decades, to as few as 23,000 to 35,000 wild individuals (8, 10). If managed optimally, Africa’s PAs could theoretically support three to four times more wild lions than the current continental total, which would secure the ecosystems that lions encompass and allow for conservation gains for many other species (3).

Investing more financial resources into Africa’s PAs would not only strengthen the conservation of lions and their ecosystems, but also generate social and economic benefits for Africa and the world at large. Africa’s PAs encompass species and areas of natural heritage that are of great symbolic and cultural significance both within Africa and elsewhere, perhaps most notably in the West (4, 11, 12). PAs also support and supply vital ecosystem services to African countries (13–15) and bolster and diversify rural and national economies via nature-based tourism (9, 16–18). Visitation to parks and reserves has been increasing in Africa to the extent that, in Southern Africa, for instance, ecotourism generates as much revenue as farming, forestry, and fishing combined (19, 20).

However, Africa’s PAs are often underfunded and receive less international support than their global value merits or than is required to unlock their economic or ecological potential. While many African governments spend proportionally more on PA networks relative to their economic means than countries in other parts of the world (21), rapidly declining wildlife populations and the poaching crisis in Africa indicate that such expenditures are insufficient to protect wildlife (22). In addition, funding levels are widely divergent among African countries, with a handful of countries investing sufficiently, while the majority invests far less than is required for the effective functioning of PAs (23). Continent-wide funding of PAs is so low that most African countries risk losing the majority of their remaining wildlife resources before they have chance to benefit from them in economic terms (11). As PAs become depleted and ecologically degraded, benefits from tourism earnings decrease relative to those from conversion of the land to agriculture or development, making PAs increasingly difficult to justify in economic and political terms (24, 25). As a result, many PAs have already been downsized, downgraded, or degazetted (9, 26).

Investment in PAs must clearly be increased, but by how much is unclear. Budgets are notoriously challenging to track due to some state wildlife authorities’ unwillingness to make their budgets available publicly and the variations in accounting methodologies between countries (27). Reputable estimates for African PA budgets are valuable but are now 10 to 34 y out of date due to the rapidly increasing and diversifying anthropogenic pressures on PAs (23, 28–30). A reassessment of the costs of maintaining Africa’s PAs amid current threats is urgently needed.

Lions are a useful species for assessing funding requirements for PAs. The species is listed as vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List (31) and is affected by a wide range of threats, including habitat loss, prey depletion, retaliatory killing by people, and targeted poaching, which also drive declines in many other wildlife species. Hence, their conservation status is emblematic of the human pressures facing wildlife more generally in Africa (10). Because lions are a keystone and umbrella species, adequate investment to secure their future is likely to protect numerous other species, as well as preserve ecosystem function and safeguard the long-term viability of Africa’s PAs (4, 32).

Here, we report on the funding available for Africa’s PAs with lions and use three different methods to estimate the minimum amount required for effective conservation of the species. We also explore associations among funding, management capacity, and PA characteristics to identify the patterns and magnitude of financial shortfalls. This work provides a minimum financial target for conserving lions and, more broadly, for securing prey populations and the ecological and economic services offered by PAs on which people and biodiversity depend.

Results

We collected funding data for 282 PAs covering 1.2 million square kilometers in 23 of 27 African lion-range countries (see Methods for information on data availability). Africa’s PAs with lions receive a minimum of $381 million in total funding annually (Table 1). Annual funding varied widely among individual PAs, from $6/km2 to $17,449/km2, with a median of $200/km2. When PAs were aggregated at a national scale, PAs in Cameroon received the lowest investment (median of $21/km2), while PAs in four other countries (Angola, Niger, South Sudan, and Senegal) also received less than $50/km2 in total funding (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Even Tanzania, which supports ∼40% of the global lion population, and most of the other countries that contain at least 1,000 lions (Zambia, Central African Republic, Mozambique, Botswana, and Zimbabwe; ref. 8), suffer from severe underresourcing, with median budgets of less than $300/km2 (Table 1). Some countries, like Tanzania, are characterized by relatively higher budgets for national parks but lower budgets for other types of PAs, which comprise the majority of the protected estate. At the other end of the spectrum, three countries showed budgets above $1,600/km2 (Kenya, Rwanda, and South Africa; Table 1). Regional funding was marginally higher in East Africa (median of $265/km2) than in Southern ($200/km2) or West-Central Africa (262/km2; SI Appendix, Table S1).

Table 1.

Management funding and estimated minimum need for effective lion conservation in PAs with lions, aggregated by country

| Rank | Country (ISO code) | Region | Total funding | State funding | Donor funding | Minimum required funding,* $mil | PAs with lions, n | Lion PA total area, km2 | |||||

| Median, $/km2 | Total, $mil | Median, $/km2 | Total, $mil | Median, $/km2 | Total, $mil | African Parks Network | Our study | Packer et al. (5) | |||||

| 1 | South Africa (ZAF) | Southern | 3,014† | 57.59† | 3,014 | 57.59 | No data | No data | 28.09 | 36.51 | 58.31 | 9 | 28,725 |

| 2 | Rwanda (RWA) | East | 2,206 | 2.25 | 245 | 0.25 | 1,960 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.30 | 2.07 | 1 | 1,020 |

| 3 | Kenya (KEN) | East | 1,688 | 59.61 | 1,435 | 51.95 | 82 | 7.66 | 35.39 | 46.00 | 73.47 | 20 | 36,190 |

| 4 | Chad (TCD) | West-Central | 753† | 2.29† | No data | No data | 753 | 2.29 | 2.98 | 3.87 | 6.18 | 1 | 3,043 |

| 5 | Malawi (MWI) | Southern | 690 | 2.79 | 6 | 0.04 | 681 | 2.75 | 4.44 | 5.77 | 9.22 | 4 | 4,540 |

| 6 | Benin (BEN) | West-Central | 557 | 6.27 | 54 | 0.80 | 498 | 5.46 | 12.54 | 16.30 | 26.03 | 6 | 12,822 |

| 7 | Uganda (UGA) | East | 418 | 5.50 | 332 | 2.96 | 85 | 2.54 | 9.66 | 12.56 | 20.05 | 9 | 9,879 |

| 8 | Burkina Faso (BFA) | West-Central | 370 | 3.37 | 207 | 1.62 | 164 | 1.75 | 10.46 | 13.60 | 21.72 | 13 | 10,700 |

| 9 | Zimbabwe (ZWE) | Southern | 241 | 16.06 | 235 | 10.32 | 1 or 272‡ | 5.75 | 42.94 | 55.80 | 89.12 | 22 | 43,903 |

| 10 | Botswana (BWA) | Southern | 200 | 42.46 | 189 | 39.26 | 11 | 3.20 | 203.16 | 264.03 | 421.69 | 49 | 207,731 |

| 11 | Tanzania (TAZ) | East | 176 | 85.74 | 41 | 62.24 | 54 | 23.50 | 173.27 | 225.18 | 359.64 | 37 | 177,164 |

| 12 | Namibia (NAM) | Southern | 166 | 17.07 | 0 | 13.29 | 35 | 3.78 | 63.34 | 82.31 | 131.47 | 10 | 64,763 |

| 13 | Mozambique (MOZ) | Southern | 135 | 24.09 | 4 | 1.87 | 121 | 22.22 | 114.56 | 148.88 | 237.79 | 21 | 117,138 |

| 14 | Central African Republic (CAF) | West-Central | 128 | 3.66 | 29 | 0.27 | 84 | 3.39 | 8.80 | 11.44 | 18.27 | 4 | 8,999 |

| 15 | Democratic Republic of the Congo (COD) | West-Central | 116 | 11.19 | 0 | 0.00§ | 116 | 11.19 | 47.70 | 61.99 | 99.01 | 5 | 48,771 |

| 16 | Zambia (ZMB) | Southern | 116 | 23.88 | 70 | 10.88 | 46 | 13.00 | 151.94 | 197.46 | 315.38 | 35 | 155,361 |

| 17 | Nigeria (NGA) | West-Central | 103 | 0.58 | 58 | 0.37 | 45 | 0.21 | 6.47 | 8.41 | 13.42 | 2 | 6,613 |

| 18 | Ethiopia (ETH) | East | 63 | 6.80 | 45 | 2.21 | 35 | 4.59 | 47.78 | 62.09 | 99.17 | 17 | 48,852 |

| 19 | Senegal (SEN) | West-Central | 47 | 0.39 | 31 | 0.26 | 16 | 0.13 | 8.05 | 10.47 | 16.72 | 1 | 8,234 |

| 20 | South Sudan (SSD) | East | 45 | 2.94 | 9 | 0.60 | 4 | 2.34 | 73.35 | 95.32 | 152.24 | 9 | 74,996 |

| 21 | Niger (NER) | West-Central | 43 | 0.11 | 26 | 0.06 | 17 | 0.04 | 2.93 | 3.81 | 6.09 | 2 | 3,000 |

| 22 | Angola (AGO) | Southern | 34 | 2.66 | ∼0¶ | ∼0.00¶ | 34 | 2.66 | 76.76 | 99.75 | 159.32 | 1 | 78,484 |

| 23 | Cameroon (CMR) | West-Central | 21 | 3.42 | 12 | 0.38 | 9 | 3.04 | 47.57 | 61.82 | 98.74 | 4 | 48,642 |

| All countries | 200 | 380.72 | 104 | 257.21 | 55 | 123.50 | 1173.18 | 1524.65 | 2435.13 | 282 | 1,199,570 | ||

Countries are ranked from highest to lowest average (median) total available funding among PAs. Minimum required funding was estimated using three different methods of calculating the minimum funding requirement for effective lion conservation. ISO, International Organization for Standardization; $mil, million dollars.

Minimum funding requirement based on each method: African Parks Network, $978/km2; our study, $1,271/km2; and Packer et al. (5), $2,030/km2.

Represents an underestimation, as South Africa estimates did not include donor data and Chad did not include state data.

Median does not accurately represent the right-skewed distribution of donor funding in Zimbabwe, where 50% of 22 PAs received <$1/km2 and 50% received a median of $272/km2.

State contributions for the Democratic Republic of the Congo totaled ∼$3,000.

Data were not available, but experts indicated that state budgets were close to $0/km2.

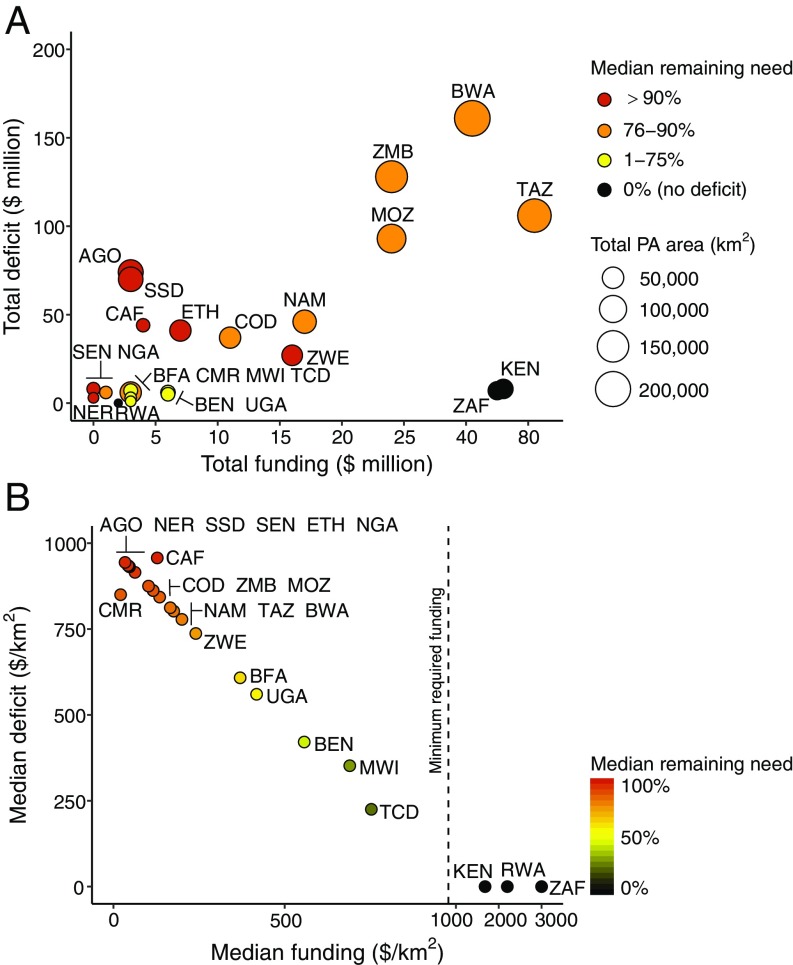

Fig. 1.

The most underfunded countries for lion conservation, in terms of total available (A) and median available (B) funding and remaining shortfalls for effective conservation of Africa’s protected areas (PAs) with lions. Median remaining need represents the average percentage of funding needed to meet the estimated required minimum. Minimum required funding and deficits represent lower-end estimates based on the African Parks Network method ($978/km2). See Tables 1 and 2 for the number of deficit PAs in each country, country rankings, and International Organization for Standardization country codes.

Three independent methods estimated that an annual minimum funding requirement of ∼$1,000 to $2,000/km2 is necessary, on average, for PAs to effectively conserve lions. African Parks Network spent a mean of $978/km2 (SD, $773/km2) per year (range, $497 to 1,833/km2). Our study model determined a higher threshold of $1,271/km2 for effective PAs (95% CI, $457 to $2,423/km2) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 and Table S2). Packer et al.’s (5) inflation-adjusted estimate represented the highest requirement at $2,030/km2.

These estimates predict that Africa’s PAs with lions require a total of at least $1.2 to $2.4 billion annually to conserve lions effectively (Table 1). Among countries, total funding requirements generally varied with the number of PAs and the number of PAs with lions; for example, from as low as $1 million in Rwanda (n = 1 PA with lions) and $3 million in Niger (n = 2) and Chad (n = 1), to as high as $173 million in Tanzania (n = 37) and $203 million in Botswana (n = 49), based on the African Parks Network method (Table 1).

In comparing available funding with required funding for effective conservation, we estimated a total annual deficit ranging from $0.9 to $2.1 billion across all assessed PAs (SI Appendix, Table S3). Funding deficits existed in 88% (African Parks Network) to 94% [Packer et al. (5)] of PAs with lions (Fig. 2). Of 23 countries assessed, 22 (96%) had at least one PA with deficit, and PAs in only three countries were funded above minimum funding requirements on average [Kenya, South Africa, and Rwanda (Rwanda was the only country without PA deficit; however, as stated earlier, Rwanda has n = 1 PA with lions) Fig. 1B, Table 2, and SI Appendix, Table S4]. As expected, the highest total deficits occurred in countries with the most and largest PAs with lions: in Botswana (n = 49 PAs with lions), Zambia (n = 35), Tanzania (n = 37), and Mozambique (n = 21) (Fig. 1A). In ranking countries by median deficit per square kilometer, the highest deficits occurred in the Central African Republic ($944 to $2,009/km2; n = 4) and Angola ($944 to $1,996/km2; n = 1), where only 1 to 2% and 2 to 3% of funding needs were met on average, respectively (Fig. 1B and Table 2).

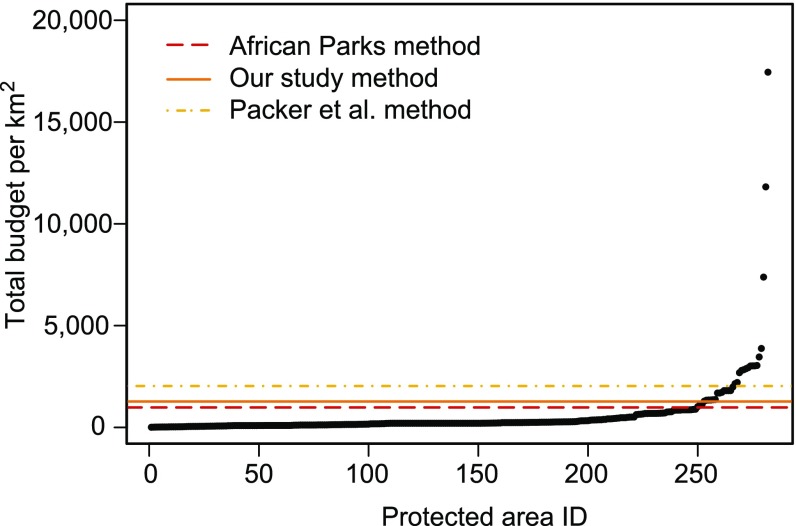

Fig. 2.

Annual funding ($/km2) for 282 African PAs with lions (black circles) compared with minimum required need as estimated by the African Parks Network method ($978/km2), our study method ($1,271/km2), and the Packer et al. (5) method ($2,030/km2). Of the 282 PAs, 249 (88%), 252 (89%), and 266 (94%) failed to meet the minimum benchmarks of the African Parks Network, our study, and Packer et al. methods, respectively.

Table 2.

The most underfunded countries for protected area (PA) management and lion conservation

| African Parks Network | Our study | Packer et al. (5) | ||||||||

| Rank | Country (ISO code) | Median deficit, $/km2 | Median remaining need,* % | PAs with deficit,† % | Median deficit, $/km2 | Median remaining need,* % | PAs with deficit,† % | Median deficit, $/km2 | Median remaining need,* % | PAs with deficit,† % |

| 1 | Central African Republic (CAF) | 957 | 98 | 100 | 1,250 | 98 | 75 | 2,009 | 99 | 100 |

| 2 | Angola (AGO) | 944 | 97 | 100 | 1,237 | 97 | 100 | 1,996 | 98 | 100 |

| 3 | Niger (NER) | 935 | 96 | 100 | 1,228 | 97 | 100 | 1,987 | 98 | 100 |

| 4 | South Sudan (SSD) | 933 | 95 | 100 | 1,226 | 96 | 100 | 1,985 | 98 | 100 |

| 5 | Senegal (SEN) | 931 | 95 | 100 | 1,224 | 96 | 100 | 1,983 | 98 | 100 |

| 6 | Ethiopia (ETH) | 915 | 94 | 94 | 1,208 | 95 | 94 | 1,967 | 97 | 100 |

| 7 | Nigeria (NGA) | 875 | 89 | 100 | 1,168 | 92 | 100 | 1,927 | 95 | 100 |

| 8 | Zambia (ZMB) | 862 | 88 | 100 | 1,155 | 91 | 100 | 1,914 | 94 | 100 |

| 9 | Democratic Republic of the Congo (COD) | 862 | 88 | 100 | 1,155 | 91 | 100 | 1,914 | 94 | 100 |

| 10 | Cameroon (CMR) | 850 | 87 | 75 | 1,143 | 90 | 100 | 1,902 | 94 | 100 |

| 11 | Mozambique (MOZ) | 843 | 86 | 86 | 1,136 | 89 | 90 | 1,895 | 93 | 95 |

| 12 | Namibia (NAM) | 812 | 83 | 100 | 1,105 | 87 | 100 | 1,864 | 92 | 100 |

| 13 | Tanzania (TAZ) | 802 | 82 | 92 | 1,095 | 86 | 95 | 1,854 | 91 | 95 |

| 14 | Botswana (BWA) | 778 | 80 | 100 | 1,071 | 84 | 100 | 1,830 | 90 | 100 |

| 15 | Zimbabwe (ZWE) | 737 | 75 | 100 | 1,030 | 81 | 100 | 1,789 | 88 | 100 |

| 16 | Burkina Faso (BFA) | 608 | 62 | 100 | 901 | 71 | 100 | 1,660 | 82 | 100 |

| 17 | Uganda (UGA) | 560 | 57 | 89 | 853 | 67 | 89 | 1,612 | 79 | 89 |

| 18 | Benin (BEN) | 421 | 43 | 100 | 714 | 56 | 100 | 1,473 | 73 | 100 |

| 19 | Malawi (MWI) | 352 | 29 | 50 | 581 | 46 | 75 | 1,340 | 66 | 75 |

| 20 | Chad (TCD) | 225 | 23 | 100 | 518 | 41 | 100 | 1,277 | 63 | 100 |

| 21 | South Africa (ZAF) | 0 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 22 |

| 22 | Kenya (KEN) | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 343 | 17 | 85 |

| No deficit | Rwanda (RWA) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All countries | 778 | 80 | 93 | 1,071 | 84 | 94 | 1,830 | 90 | 95 | |

Countries are ranked from highest to lowest median deficit among PAs with lions, as estimated by the African Parks Network method, the approach with the lowest minimum funding requirement ($978/km2). More detail on PA deficits in countries that contain very few PAs with deficits (e.g., Kenya and South Africa) can be found in SI Appendix, Table S4, which shows median deficits by country calculated using only PAs with deficits. ISO, International Organization for Standardization.

Median percent of unmet minimum required funding relative to total available funding by PA.

See Table 1 for total number of PAs with lions in each country.

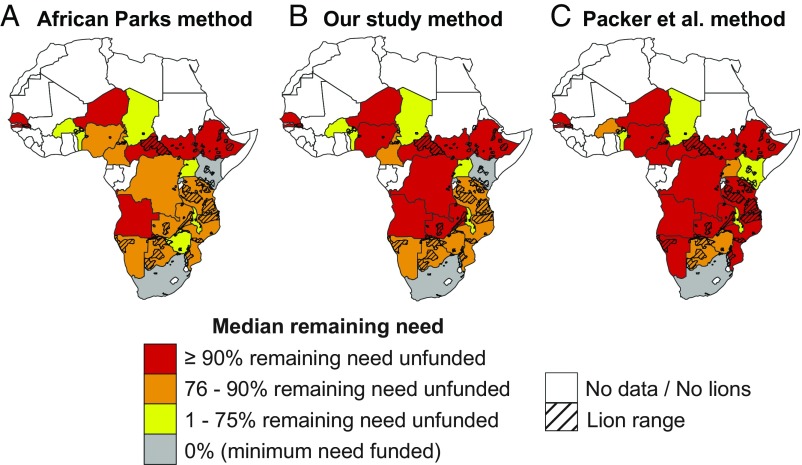

In PAs with deficits, just 10 to 20% of funding requirements were available on average (SI Appendix, Table S4). Funding shortfalls were widespread and extensive: 27 to 59% of countries in deficit showed shortages of >90% of required funding on average (Fig. 3). The vast majority of countries (87%) reported lower average available funding per square kilometer across all PAs than even the lowest $978/km2 amount estimated as necessary for effective conservation of lions (Table 1). Only three of all countries assessed (South Africa, Rwanda, and Kenya) showed average funding levels higher than the minimum needed (Table 1), and even in these relatively well-funded countries, a significant proportion of PAs showed deficits (2 of 13 PAs in South Africa and up to 17 of 20 PAs in Kenya; Fig. 1 and Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Average funding shortfalls for lion conservation in PAs in 23 of 27 lion-range countries. Median remaining need represents the average (median) funding shortfall in PAs, calculated by comparing available funding for PA management to the required funding to effectively conserve lions. Minimum funding requirements were based on three estimation methods: (A) African Parks Network ($978/km2 per year), (B) our study method ($1,271/km2), and (C) Packer et al. (5) method ($2,030/km2). We note that “0% (minimum need funded)” does not imply that all PAs for that country are adequately funded, as PA budgets vary significantly within countries. For example, despite Kenya achieving median funding need, at least 40% of PAs in that country are not sufficiently funded. All assessed countries, except Rwanda, showed at least one PA with deficit. See Table 2 and SI Appendix, Table S4 for more details on median deficit and the number of PAs with funding shortfalls in each country.

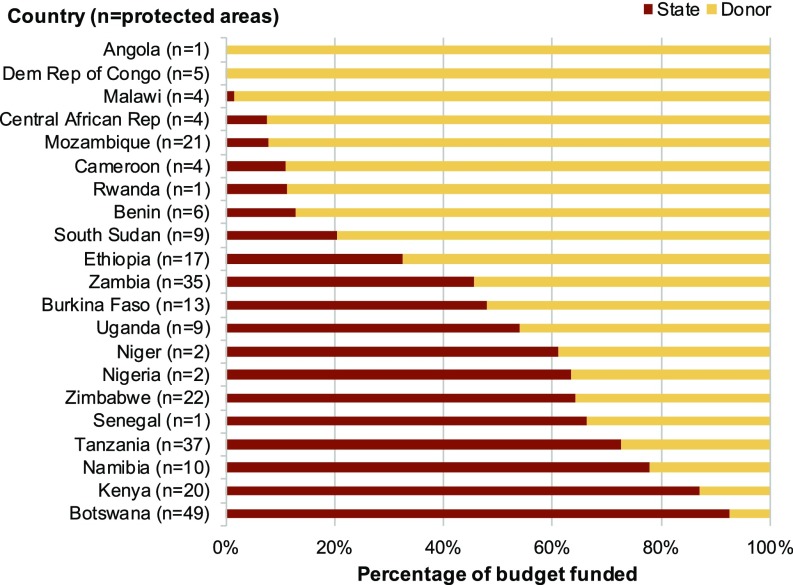

State funding was twice as large as donor support (Table 1). State funding per unit area was more than three times as high in Southern Africa than in other regions, whereas donor funding per unit area was higher in West-Central Africa than in other regions (SI Appendix, Table S1). Accordingly, several countries in Southern Africa (Botswana and Namibia) and East Africa (Kenya and Tanzania) were especially reliant on state support, while several countries in West-Central Africa (Democratic Republic of the Congo and Central African Republic) and Southern Africa (Angola and Malawi) were largely reliant on donor contributions (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Proportion of state versus donor contributions to management funding in 272 of Africa’s PAs with lions. Data excludes South Africa and Chad, for which data were not available on donor and state contributions, respectively.

Higher funding per square kilometer was associated with smaller-sized, fully fenced PAs that contained rhinos, supported active tourism, were part of a Transfrontier Conservation Area (TFCA), were jointly managed by a nonprofit organization, and were located in a country with lower corruption (model fit R2 = 0.98; SI Appendix, Fig. S2 and Table S5). Donor contributions were higher in smaller, fully fenced PAs of IUCN category I or II that supported active tourism, were comanaged by a nonprofit partner, and were located in countries with lower gross domestic product (GDP) (R2 = 0.91; SI Appendix, Tables S6 and S7). Greater state funding was associated with smaller PAs that contained rhinos, were part of a TFCA and IUCN category I or II located in East Africa and in countries with higher GDP, and were not comanaged by a nonprofit (R2 = 0.91; SI Appendix, Table S8).

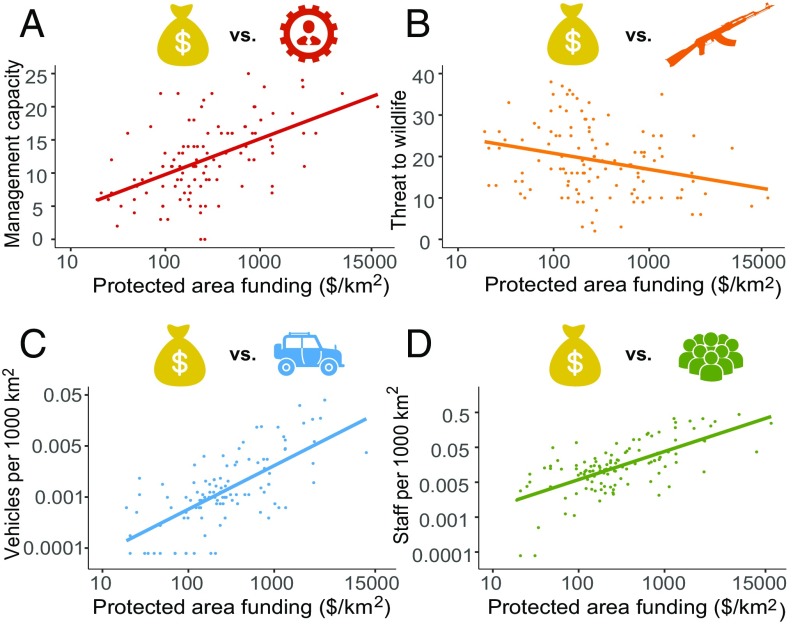

Among PAs, higher funding per square kilometer was associated with higher management capacity (r = 0.54, P < 0.001; Fig. 5A), lower threat to wildlife (r = −0.28, P = 0.001; Fig. 5B), and the availability of more patrol vehicles and staff (r = 0.71 and r = 0.67, respectively, both P < 0.001; Fig. 5 C and D). In turn, greater management capacity was associated with a lower threat to wildlife (r = −0.28, P = 0.003) and more staff and vehicles (r = 0.42 and r = 0.44, respectively, both P < 0.001).

Fig. 5.

Associations between funding in 125 of Africa’s PAs with lions and management capacity (A), threats to wildlife (B), vehicles available for patrols (C), and number of staff (D). The 125 PAs are a subset of the 282 state-owned PAs for which both funding and the relevant data were available. Lines indicate the directionality of Pearson correlations.

Discussion

Our findings reveal major deficits in the management funding of Africa’s PAs with lions. For PAs to achieve baseline effective conservation of lions (which reflects effective management more generally), overall funding must be increased by three to six times to meet minimum need—that is, adding $0.9 to $2.1 billion to supplement the $381 million of total annual funding already available. Existing funding is highly skewed, with a minority of PAs funded above minimum required levels, while the majority of PAs and countries receive a fraction of the funding needed to conserve lion populations and broader ecosystems effectively. In some countries (e.g., Zimbabwe), although moderate funding from the state is available, substantial proportions are tied up for salaries, leaving modest amounts for operations. Unless action is taken to increase resources for most PAs in African savannahs, lions and many other species are likely to suffer continued steep declines in number and distribution, with serious ecological and economic ramifications. Countries with some of the largest PA networks, such as Botswana, Tanzania, and Zambia, experience some of the largest deficits despite strong political commitments to conservation. This presents an opportunity for additional donor support for conservation efforts in these countries, given the impressive contribution of land for conservation, the difficulty associated with securing such vast areas, and the significance of these areas for the conservation of a wide range of species valued worldwide.

Our results are consistent with prior studies in highlighting the importance of management budgets for effective conservation of African wildlife. Inadequate PA funding in part leads to the wildlife population declines observed in many of Africa’s PAs and helps explain the severity of declines in charismatic species such as rhinos, elephants, and, increasingly, lions (3, 5, 10, 33–35). Our finding that lower funding was associated with greater threats to wildlife suggests that management funding does not scale with the degree of threat and that threats are exacerbated in the absence of adequate funding. Adequate budgets are required to develop and maintain infrastructure; to purchase and maintain vehicles and other equipment; and to train, deploy, and motivate staff (2, 36). In the absence of sufficient funding (and even with adequate funding in circumstances of weak PA governance and management), field staff can become ineffective. In the worst cases, poorly paid or unmotivated staff can actually contribute to wildlife declines due to the social and financial gains that can be derived from engaging in illegal activities such as poaching (37).

Efforts are drastically needed to raise the management budgets of PAs to $1,000 to 2,000/km2 to effectively conserve lions and their broader ecosystems. The African Parks Network method ($978/km2) represented the tried-and-true costs of managing stable and increasing lion populations in nine effective PAs with varying management conditions. African Parks have proven highly effective in the field and also at fundraising, due in part to their commitment to financial accountability. The African Parks Network method may yield the lowest estimates of budget requirements because their budgets are less likely to be affected by leakages to corruption or inefficiencies than those of some state wildlife authorities. Channeling an elevated proportion of funding to PAs through accountable nongovernmental organization (NGO) partners engaged in collaborative management partnerships represents one potential means of reducing loss of donor funding to corruption (38). Efforts to build the capacity of PA authorities to manage finances transparently are also important. Our study method ($1,271/km2) considered a broader spectrum of management conditions across 115 PAs with lions and identified the funding threshold that best predicted PAs maintaining lion populations at ≥50% of carrying capacity. Packer et al.’s (5) method ($2,030/km2) represented the high-end costs associated with managing unfenced, free-roaming lion populations. Collectively, these estimates represent a gradient of real-world management conditions and costs for effectively conserving lions. Although estimates are higher than prior (and now outdated) estimates of required funding, such as $174 to 424/km2 for forest parks in Central Africa in 2004 (29) and $459/km2 for parks Africa-wide in 1984 (28), our estimates approximate the $1,010/km2 estimated need for managing tigers in Asia (39) [all figures in 2015 US dollars (USD)].

We emphasize that the two higher-end estimates ($1,271/km2 and $2,030/km2, or $1.2 to $2.4 billion total annually across all PAs with lions) are the minimum amounts necessary under current conditions to manage lion populations at half of the potential population size. However, 50% of carrying capacity is a low benchmark for conservation effectiveness, particularly for lions, which have such great ecological and economic value. In addition, some of the PAs with lions at 50% of estimated carrying capacity are suffering ongoing declines (10) such that even larger budgets may be required to manage stable or growing populations of lions and their prey and yield long-term security for the species.

Additional Considerations.

We caution that our study does not provide insights into the requirements for the management of individual PAs, which likely vary significantly with the extent of threat and the geographic location, habitat type, and degree of remoteness. Large PAs are likely to benefit from economies of scale, as certain infrastructure developments are necessary regardless of the size of an area and because larger areas will be more insulated from threats than smaller areas. Similarly, costs are likely to be higher in countries in which corruption causes funding to be squandered (40). Additionally, in PAs where there is little or no infrastructure, such as the newly gazetted Luengue-Luiana and Mavinga national parks in Angola, the required capital investment would be significantly greater than the operational costs used in our calculations. If PAs were to receive the increase in funding that we recommend, all wildlife species would benefit; with that said, our estimates may not reflect the additional funding potentially needed to conserve rhinos due to the high prices obtained by illegal wildlife traders for their horns and the vigor with which poachers pursue them (41–43).

The costs of managing Africa’s PAs and conserving species such as lions are likely to grow with time. Pressure on wildlife due to poaching for body parts for the illegal wildlife trade is severe, with an increasing range of species being affected (including lions), which makes PA management more difficult and expensive (3, 43). The human population is growing faster in Africa than in other parts of the world, which will increase pressure for land and natural resources contained within PAs (44, 45). Conversely, costs could be reduced by increasing the involvement of neighboring communities in PA management and decision making, thereby increasing their engagement and sense of ownership (12, 16, 46).

Funding Protected Areas for Africa’s Future.

Greater investment in Africa’s PAs is urgently needed, and is likely to yield significant social, economic, and ecological benefits. PAs provide essential ecosystem services via the provisioning of clean water and other natural resources (13–15), which can reduce poverty, promote human health, and improve the well-being of rural communities (47, 48). Wildlife-based tourism in PAs has significant potential to act as a vehicle for sustainable economic development and job creation in many African countries, particularly in rural areas with few alternatives (7). The tourism industry already generates $34 billion of revenue in Sub-Saharan Africa and creates nearly 6 million jobs (49, 50). Lions represent a key aspect of this success and are one of the most popular attractions to visitors of Africa’s PAs (51). Tourism revenue represents a crucial means for African countries to diversify economies and reduce reliance on finite resources such as minerals, and on agriculture and livestock, which are vulnerable to climate change (52). The potential social and economic benefits associated with functioning PA networks build a strong case for the investment of general development aid funding to augment the traditional conservation-focused funding in PA management. An allocation of just 2% of the $51 billion allocated to development in Africa would likely cover the deficits facing PAs from a lion-conservation perspective (53). Such investments to PAs should be normalized as part of the international development financial portfolio to support maturing tourism economies and protect the environmental services provided by PAs to people’s health and general well-being. These benefits would increase if care were taken to maximize the extent to which benefits from tourism and PAs accrue to communities. Potential approaches include providing communities with part or complete ownership of concessions within PAs and, when funding permits, the use of performance payments (54, 55), taking care to avoid elite capture. Similarly, developed countries could consider debt-for-nature schemes, in which debt alleviation is provided in return for PA investment by the host nation (56). Creative donor investment could assist many African countries to optimize the commercial viability of their PAs, especially in PAs with high deficits (Fig. 1) and for which state funding is in short supply (Fig. 4).

Over recent years, increasing effort has promoted community-based conservation areas outside of PAs, which are essential for maintaining landscape connectivity and intact ranges of far-roaming species such as lions. However, while such investments are essential, we urge the conservation and donor community to ensure that sufficient focus is given to the management and protection of PAs to maintain the backbone of conserved landscapes. PAs should not be assumed to be adequately protected by virtue of their legal status. In addition to funding needs, improving the effectiveness with which existing funds are used is also essential. This means avoiding corruption and seeking options to provide long-term, drip-feed funding for PAs, rather than the large, nonrecurrent funding packages commonly provided by multilateral funding agencies (11). To this end, collaborative management partnerships between NGOs and state wildlife authorities (such as those practiced by African Parks) are of potentially high value and should be a funding priority (38).

Conclusion

PAs in Africa are facing a funding shortfall of at least $0.9 billion and up to $2.1 billion for effective conservation of lions. Without significant increases in the amount of funding, PAs will not be able to fulfill the ecological, economic, or social objectives for which they were established. The current budget deficit facing Africa’s PAs is surmountable but currently represents a great risk that lions and many other wildlife species will continue to decline in number and ultimately disappear from the majority of PAs in lion range (10). Such losses would mean that many African countries would lose their most iconic wildlife species before benefitting significantly from them.

Methods

Our methods comprised four main steps. First, we compiled a database of available funding in PAs with lions, which to our knowledge represents the most comprehensive and up-to-date database of its kind. Second, we applied three methods to estimate different thresholds of minimum funding required for effective conservation of lions. Third, we used required funding estimates to calculate deficits in PAs for which available funding did not meet need. Fourth, we addressed the patterns and importance of funding for conservation by examining associations between funding and PA characteristics and management resources.

Available Funding.

We gathered data on the total funding available for management of PAs. Our study focused on state-owned PAs containing lions and located within lion range in Africa (SI Appendix, Appendix 1). Total funding comprised state funding (contributed by the PA country government) and donor funding (contributed by nonstate groups, including nonprofit organizations, charitable foundations, and bi- and multilateral agencies). Management funding included costs related to staff, law enforcement, maintenance of infrastructure and roads, habitat management, and engagement with adjacent communities. Sources (see SI Appendix, Appendix 2 for details) broadly included (i) expert surveys (see ref. 3 for methods), (ii) wildlife authorities, (iii) 50 nonprofit organizations involved in PA management, (iv) private hunting companies, and (v) major donors involved in PA management, such as foundations, nonprofit organizations, and multilateral government agencies. We obtained both state and donor funding data from 282 state-owned PAs with lions in 23 countries, except for Chad, for which we were not able to obtain state data, and South Africa, for which we could not comprehensively capture donor contributions [however, state budgets for PAs in South Africa are substantially higher than in other countries and sufficient for effective lion management (3)]. We emphasize the major challenges associated with obtaining budget data and that our estimates of donor support are likely underestimates (SI Appendix, Appendix 3). Nonetheless, we are confident that our estimates are of the correct order of magnitude and constitute the most up-to-date and accurate data available.

From each source, we gathered information on the PA and the years over which funding was spent, tracking whether funds were channeled to other organizations to avoid double counting resources. We primarily obtained budget data for the fiscal year spanning 2015 to 2016, but in rare cases in which data were not otherwise available, we included data from several years before (no earlier than 2009) or after (2017). All financial data (and numbers reported in this paper) were converted to USD at the average exchange rate from the year of origin (57) and scaled to USD in 2015 to account for inflation (58). To comply with requests for anonymity from our informants and reduce the vulnerability of poorly funded PAs (exposure to funding levels could make them a target for threats such as poaching), we report results on individual PA data without mentioning PAs by name and present aggregated PA data at the country level. However, upon request, we will provide data to researchers or conservationists who demonstrate constructive ideas for further analysis. We calculated PA average funding (including funding requirements and deficits) using medians to prevent misrepresentation due to a minority of highly funded PAs. All statistical analyses were done using R (59).

Minimum Funding Requirements and Deficits.

We applied three methods to consider a range of cost estimates of the minimum funding required for effective lion conservation:

-

i)

African Parks Network method: We acquired data on management budgets for each PA managed by the African Parks Network, a nonprofit organization delegated management responsibility by state wildlife authorities for nine PAs as of 2015. Since both lions and prey species were stable or increasing in all nine PAs (3), we assumed that the levels of management investment were adequate for effective lion conservation. We calculated the minimum funding requirement as the amount that African Parks Network spent in 2015 on capital investments plus operating costs associated with management in each of their PAs. Capital investments included buildings, roads, airstrips, fencing, vehicles, aircraft, office equipment, furniture, tools, radio communications equipment, and other fixed assets.

-

ii)

Our study method: We used logistic regression to determine the minimum funding level that best predicted PA effectiveness for 115 PAs for which we had funding and lion population data. We defined effective PAs as PAs where lions occurred at ≥50% of estimated carrying capacity (3). Lion biomass is strongly correlated with prey biomass (60), which in turn, is dictated primarily by rainfall and soil (61–63). We estimated the potential carrying capacity for lions in each PA based on the following equation (64):

where ungulate biomass was estimated based on local rainfall (calculated by cold cloud duration) and soil characteristics (cation exchange capacity). We acquired data on potential carrying capacity for lions at each PA (64) and paired these with data on lion population estimates from ref. 3. Using effectiveness as a predictor variable and total funding [USD per square kilometer ($/km2)] as a required response variable from a pool of 35 candidate variables (SI Appendix, Table S1), we built a multivariate model to predict PA effectiveness. We then identified the funding threshold that best discriminated effective from noneffective PAs (see SI Appendix, Appendix 4 for details).

-

i)

Packer et al. (5) method: We applied Packer et al.’s finding based on 22 PAs that $2,000/km2 of operational costs is required to maintain lions in unfenced PA at ≥50% carrying capacity, representing the high-end costs of managing free-roaming lions. Expert surveys indicated that most of the PAs in our dataset were unfenced (72%). We adjusted Packer et al.’s estimate to USD in the year 2015.

Using these estimates of required funding, we calculated funding needs and deficits (in USD) for each PA and then aggregated PAs by country. PA funding need was calculated as the minimum funding requirement ($/km2) multiplied by PA area (km2). PA funding deficit was calculated as the funding need minus available funding (positive deficits indicate greater need than available funding, and deficits were minimized at $0, since our approach aimed to assess baseline funding adequacy). PA funding deficit per area ($/km2) was calculated as PA deficit divided by PA area. Country totals for funding need and deficit were calculated by summing PA need and deficit, respectively, for PAs in each country. When calculating budget deficits on a national and continental level, budget surpluses that occurred in a minority of PAs were not carried over to other PAs to reduce overall estimated deficit, but were treated as zero deficit, reflecting the fact that such surpluses are generally not transferred to other PAs.

PA Characteristics.

We used a linear regression framework to assess what PA characteristics were associated with higher total, state, and donor funding (see SI Appendix, Appendix 4 for details). For this analysis, we used a subset of 128 PAs for which we had expert information from surveys. We assessed 36 variables (derived from a range of sources, including published papers, publicly available datasets, and expert surveys) relating to governance, socioeconomic, management, and ecological characteristics for each PA (SI Appendix, Table S9).

Management Factors.

Expert surveys also collected information on how funding was associated with management resources and threats to wildlife. Experts were asked to provide information (see ref. 3 for details) on (i) the number of vehicles and rangers available for management; (ii) a rating of different aspects of management capacity on a scale of 1 to 5, which we summed to generate an overall management capacity score; and (iii) a rating of the severity of 11 specific threats to wildlife on a scale of 1 to 5, which we summed to generate an overall threat to wildlife score. We calculated Pearson correlations to examine relationships among total funding, management resources (vehicles and staff), management capacity, and threats to wildlife. As normality is a critical assumption in correlation analysis, total funding, vehicle, and staff data were log-transformed to address the right skew in the data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at the state wildlife agencies and nonprofit and donor organizations who generously provided information. We thank Elizabeth Schultz, Timothy Hodgetts, Richard Davies, Craig Packer, Kelsey Farson, Justin Brashares, and members of the Brashares laboratory at University of California, Berkeley for providing feedback that improved the manuscript. Panthera provided funding to support the study. J.R.B.M. was supported in part by National Science Foundation Coupled Human and Natural Systems Grant 115057. L.C. was funded by the US Agency for International Development.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1805048115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bruner AG, Gullison RE, Rice RE, da Fonseca GAB. Effectiveness of parks in protecting tropical biodiversity. Science. 2001;291:125–128. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5501.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hilborn R, et al. Effective enforcement in a conservation area. Science. 2006;314:1266. doi: 10.1126/science.1132780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindsey PA, et al. The performance of African protected areas for lions and their prey. Biol Conserv. 2017;209:137–149. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macdonald EA, et al. Conservation inequality and the charismatic cat: Felis felicis. Glob Ecol Conserv. 2015;3:851–866. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Packer C, et al. Conserving large carnivores: Dollars and fence. Ecol Lett. 2013;16:635–641. doi: 10.1111/ele.12091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craigie ID, et al. Large mammal population declines in Africa’s protected areas. Biol Conserv. 2010;143:2221–2228. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindsey PA, et al. Underperformance of African protected area networks and the case for new conservation models: Insights from Zambia. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riggio J, et al. The size of savannah Africa: A lion’s (Panthera leo) view. Biodivers Conserv. 2013;22:17–35. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson JE, Dudley N, Segan DB, Hockings M. The performance and potential of protected areas. Nature. 2014;515:67–73. doi: 10.1038/nature13947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauer H, et al. Lion (Panthera leo) populations are declining rapidly across Africa, except in intensively managed areas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:14894–14899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500664112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindsey PA, Balme GA, Funston PJ, Henschel PH, Hunter LTB. Life after Cecil: Channelling global outrage into funding for conservation in Africa. Conserv Lett. 2016;9:296–301. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Infield M. Cultural values: A forgotten strategy for building community support for protected areas in Africa. Conserv Biol. 2001;15:800–802. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Zyl H. 2015. The economic value and potential of protected areas in Ethiopia. Report for the Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority under the Sustainable Development of the Protected Areas System of Ethiopia Programme (Independent Economic Researchers, Cape Town, South Africa)

- 14.Egoh B, Reyers B, Rouget M, Bode M, Richardson DM. Spatial congruence between biodiversity and ecosystem services in South Africa. Biol Conserv. 2009;142:553–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Jaarsveld AS, et al. Measuring conditions and trends in ecosystem services at multiple scales: The Southern African Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (SAfMA) experience. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360:425–441. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rylance A, Spenceley A. Reducing economic leakages from tourism: A value chain assessment of the tourism industry in Kasane, Botswana. Dev South Afr. 2017;34:295–313. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gössling S. Ecotourism: A means to safeguard biodiversity and ecosystem functions? Ecol Econ. 1999;29:303–320. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snyman SL. The role of tourism employment in poverty reduction and community perceptions of conservation and tourism in southern Africa. J Sustain Tour. 2012;20:395–416. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balmford A, et al. A global perspective on trends in nature-based tourism. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scholes RJ, Biggs R. Ecosystem Services in Southern Africa: A Regional Assessment. Council for Scientific and Industrial Research; Pretoria, South Africa: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindsey PA, et al. Relative efforts of countries to conserve world’s megafauna. Glob Ecol Conserv. 2017;10:243–252. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pringle RM. Upgrading protected areas to conserve wild biodiversity. Nature. 2017;546:91–99. doi: 10.1038/nature22902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mansourian S, Dudley N. 2008. Public funds to protected areas (WWF International, Gland, Switzerland)

- 24.Kideghesho J, Rija A, Mwamende K, Selemani I. Emerging issues and challenges in conservation of biodiversity in the rangelands of Tanzania. Nat Conserv. 2013;6:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norton-Griffiths M, Southey C. The opportunity costs of biodiversity conservation in Kenya. Ecol Econ. 1995;12:125–139. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mascia MB, et al. Protected area downgrading, downsizing, and degazettement (PADDD) in Africa, Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean, 1900-2010. Biol Conserv. 2014;169:355–361. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilkie D, Carpenter JF, Zhang Q. The under-financing of protected areas in the Congo Basin: So many parks and so little willingness-to-pay. Biodivers Conserv. 2001;10:691–709. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bell RHV, Clarke JE. Funding and financial control. In: Bell R, McShane-Caluzi E, editors. Conservation and Wildlife Management in Africa. U.S. Peace Corps; Washington, DC: 1984. pp. 545–555. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blom A. An estimate of the costs of an effective system of protected areas in the Niger Delta–Congo Basin forest region. Biodivers Conserv. 2004;13:2661–2678. [Google Scholar]

- 30.James AN, Green MJBB, Paine JR. 1999 A global review of protected area budgets and staff (World Conservation, Cambridge, UK). Available at https://www.cbd.int/financial/expenditure/g-spendingglobal-wcmc.pdf. Accessed January 3, 2018.

- 31.Bauer H, Packer C, Funston PJ, Henschel PH, Nowell K. 2016 doi: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T15951A107265605.en. Panthera leo. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016 , e.T15951A115130419. Available at . . Accessed January 3, 2018. [DOI]

- 32.Ripple WJ, et al. Status and ecological effects of the world’s largest carnivores. Science. 2014;343:1241484. doi: 10.1126/science.1241484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henschel PH, et al. Determinants of distribution patterns and management needs in a critically endangered lion Panthera leo population. Front Ecol Evol. 2016;4:110. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leader-Williams N, Albon SD, Berry P. Illegal exploitation of black rhinoceros and elephant populations: Patterns of decline, law enforcement and patrol effort in Luangwa Valley, Zambia. J Appl Ecol. 1990;27:1055–1087. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geldmann J, et al. A global analysis of management capacity and ecological outcomes in terrestrial protected areas. Conserv Lett. 2018;11:e12434. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jachmann H. Monitoring law-enforcement performance in nine protected areas in Ghana. Biol Conserv. 2008;141:89–99. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindsey PA, et al. Dynamics and underlying causes of illegal bushmeat trade in Zimbabwe. Oryx. 2011;45:84–95. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baghai M, et al. Models for the collaborative management of Africa’s protected areas. Biol Conserv. 2018;218:73–82. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walston J, et al. Bringing the tiger back from the brink-the six percent solution. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:1–4. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.MacKinnon J, Aveling C, Olivier R, Murray M, Carlo P. 2015 Larger than elephants: Inputs for the design of an EU strategic approach to wildlife conservation in Africa (Publications Office of the European Union, Brussels). Available at https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/sites/devco/files/eu-wildlife-strategy-africa-synthesis-2015_en_0.pdf. Accessed January 3, 2018.

- 41.Wasser SK, et al. Genetic assignment of large seizures of elephant ivory reveals Africa’s major poaching hotspots. Science. 2015;349:84–87. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Biggs D, Courchamp F, Martin R, Possingham HP. Legal trade of Africa’s Rhino horns. Science. 2013;339:1038–1039. doi: 10.1126/science.1229998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams VL, Loveridge AJ, Newton DJ, Macdonald DW. Questionnaire survey of the pan-African trade in lion body parts. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0187060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bradshaw CJA, Brook BW. Human population reduction is not a quick fix for environmental problems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:16610–16615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410465111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gerland P, et al. World population stabilization unlikely this century. Science. 2014;346:234–237. doi: 10.1126/science.1257469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Naughton-Treves L, Holland MB, Brandon K. The role of protected areas in conserving biodiversity and sustaining local livelihoods. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 2005;30:219–252. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Naughton-Treves L, Alix-Garcia J, Chapman CA. Lessons about parks and poverty from a decade of forest loss and economic growth around Kibale National Park, Uganda. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:13919–13924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013332108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferraro PJ, Hanauer MM, Sims KRE. Conditions associated with protected area success in conservation and poverty reduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:13913–13918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011529108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.UNWTO 2014 Towards measuring the economic value of wildlife watching tourism in Africa (World Tourism Organization, Madrid). Available at sdt.unwto.org/content/unwto-briefing-wildlife-watching-tourism-africa. Accessed January 3, 2018.

- 50.WTTC 2015 Travel and tourism, the economic impact: Sub-Saharan Africa 2015 (World Travel & Tourism Council, London). Available at https://www.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/economic%20impact%20research/regional%202015/subsaharanafrica2015.pdf. Accessed January 3, 2018.

- 51.Lindsey PA, Alexander R, Mills MGL, Romañach S, Woodroffe R. Wildlife viewing preferences of visitors to protected areas in South Africa: Implications for the role of ecotourism in conservation. J Ecotour. 2007;6:19–33. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trade and Development Board 2017 Economic development in Africa Report 2017: Tourism for transformative and inclusive growth (United Nations, New York). Available at unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/aldcafrica2017_en.pdf. Accessed January 3, 2018.

- 53.OECD 2017 Development aid at a glance: Statistics by region. 2. Africa. (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, Paris). Available at www.oecd.org/dac/stats/documentupload/Africa-Development-Aid-at-a-Glance.pdf. Accessed January 3, 2018.

- 54.Ferraro PJ, Kiss A. Direct payments to conserve biodiversity. Science. 2002;298:1718–1719. doi: 10.1126/science.1078104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lapeyre R, Laurans Y. Contractual arrangements for financing and managing African protected areas: Insights from three case studies. Parks. 2017;23:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thapa B. Debt-for-nature swaps: An overview. Int J Sustain Dev World Ecol. 1998;5:249–262. [Google Scholar]

- 57.OANDA 2017 Average exchange rates. Available at https://www.oanda.com/fx-for-business/historical-rates. Accessed July 1, 2017.

- 58.US Bureau of Labor Statistics 2017 CPI inflation calculator (US Bureau of Labor Statistics,Washington, DC). Available at https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm. Accessed July 1, 2017.

- 59.R Core Team 2017 R: A Language and environment for statistical computing, v.3.5.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna). Available at www.r-project.org. Accessed January 3, 2018.

- 60.Hayward MW, O’Brien J, Kerley GIH. Carrying capacity of large African predators: Predictions and tests. Biol Conserv. 2007;139:219–229. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Coe MJ, Cumming DH, Phillipson J. Biomass and production of large African herbivores in relation to rainfall and primary production. Oecologia. 1976;22:341–354. doi: 10.1007/BF00345312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.East R. Rainfall, soil nutrient status and biomass of large African savanna mammals. Afr J Ecol. 1984;22:245–270. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fritz H, Duncan P. On the carrying capacity for large ungulates of African savanna ecosystems. Proc Biol Sci. 1994;256:77–82. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1994.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Loveridge AJ, Canney S. 2009. Report on the lion distribution and conservation modelling project: Final report (Born Free Foundation, Horsham, UK), p 58.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.