Abstract

Background

Fertility is a complex trait that has a major impact on the development of the buffalo industry. Genome-wide association study (GWAS) has increased the ability to detect genes influencing complex traits, and many important genes related to reproductive traits have been identified in ruminants. However, reproductive traits are influenced by many factors. The development of the follicle is one of the most important internal processes affecting fertility. Genes found by GWAS to be associated with follicular development may directly affect fertility. The present study combined GWAS and RNA-seq of follicular granulosa cells to identify important genes which may affect fertility in the buffalo.

Results

The 90 K Affymetrix Axiom Buffalo SNP Array was used to identify the SNPs, genomic regions, and genes that were associated with reproductive traits. A total of 40 suggestive loci (related to 28 genes) were identified to be associated with six reproductive traits (first, second and third calving age, calving interval, the number of services per conception and open days). Interestingly, the mRNA expressions of 25 of these genes were also observed in buffalo follicular granulosa cells. The IGFBP7 gene showed high level of expression during whole antral follicle growth. The knockdown of IGFBP7 in buffalo granulosa cells promoted cell apoptosis and hindered cell proliferation, and increased the production of progesterone and estradiol. Furthermore, a notable signal was detected at 2.3–2.7 Mb on the equivalent of bovine chromosome 5 associated with age at second calving, calving interval, and open days.

Conclusions

The genes associated with buffalo reproductive traits in this study may have effect on fertility by regulating of follicular growth. These results may have important implications for improving buffalo breeding programs through application of genomic information.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12864-018-5208-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Follicle, GWAS, Gene expression, IGFBP7, Reproduction

Background

Buffalo is a mono-ovular species, during whose oestrus period, generally only one follicle matures and ovulates resulting in a major reduction in fertility, which restricts the development of the buffalo industry. Reproductive traits are quantitative traits influenced by many factors. With the application of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) for mapping genes for complex traits in domestic animals (e.g., pig, cattle and sheep), many important genes related to quantitative traits have been identified [1, 2]. However, only two GWAS have been performed for buffalo reproductive traits so far [3, 4]. In our previous study, nine significant (P < 0.001) SNPs associated with buffalo reproductive traits were identified by using the BovineSNP50 BeadChip from cattle [3]. With a significance threshold of P < 10− 4, 12 markers associated with four reproductive traits (age at first calving, calving interval, number of services per conception, and open days) of Murrah buffalo were detected by using a buffalo SNP chip array (Axiom ® Buffalo Genotyping Array 90 K Affymetrix) [4]. Mutations detected by GWAS were generally located in intergenic regions [5]. Whether these mutations affect target traits through specific pathways are unknown.

A thorough understanding of the biology of reproductive traits will be beneficial to the further development of buffalo breeding programs. Genetic variations are expected to alter gene expression leading to changes in the abundance of one or multiple proteins in turn affecting the phenotype of traits [6, 7]. Next generation sequencing (NGS) technology has been developed for the analysis of mRNA expression, and it has also been used for determining candidate genes which regulate reproductive performance of cattle [8] and buffalo [9]. Integrating GWAS and RNA-seq to detect important genes associated with target traits has been reported to provide new insight into the identity of causal genes and mutations and how they may influence the trait [10–13]. Up to now no reports related to buffalo reproductive traits with the integrated techniques have been available.

The manipulation of reproduction often relies on the regulation of follicle development during oestrous cycles. The process of folliculogenesis includes primordial follicle recruitment, followed by granulosa cell (GC) proliferation, and differentiation, and antral or preovulatory follicle formation [14, 15]. Every step of the folliculogenesis process is crucial for efficient fertility. In cattle, ovulation of large prolonged dominant follicles was reported to have resulted in a decrease in fertility [16], which was thought to be attributed to a reduction in fertilization rates or early embryo survival. Furthermore, oogenesis and folliculogenesis are inextricably linked, and the growth of oocytes are interdependent on that of the granulosa cells in the follicle [17]. The genes related to follicle development are therefore speculated to be important genes affecting the reproductive performance.

The 90 K commercial buffalo SNP chip, as an appropriate available tool [18], was applied to genotype 462 Italian Mediterranean buffaloes with 1424 lactations in this study. We therefore integrated GWAS results with our previous RNA-seq results [9] to identify the key genes affecting follicular development of buffalo. Our results lay the foundation for the understanding the genetic mechanism of buffalo reproduction.

Results

Genome-wide association study

Forty top suggestive (P < 10− 4) markers were observed (Table 1), 3 to 10 of which, were associated with the different traits. According to the cattle genome reference (Bos taurus UMD3.1 assembly), the SNPs of AX-85092311, AX-85128429, and AX-85136537 were found within genes (TBCB, NDUFS2 and TRHDE). The remainders were aligned to intergenic regions (SESN3, GPATCH4, IQGAP3, COL23A1, CADM2, FSTL4, BRINP2, KCNMA1, MEF2D, IGFBP7, NUFIP2, DIAPH3, CDH10, THRB, KYNU, CSGALNACT1, ZNF503, TRHDE, HYAL4, KRR1, MTPN, PELI2, SOX21, GMDS, PRDM5 and LMO4), which were spread over 17 chromosomes. Interestingly, the SNP of AX-85178307 was associated with TCA and SCA, and another SNP AX-85127260 was associated with TCA and CI, which is in line with the correlations observed between traits.

Table 1.

Genes near to the most suggestive SNPs (P < 0.0001) for six reproductive traits

| Traits | SNP ID | Chr | Position(bp) | Within Gene | Nearst Gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCA | AX-85104022 | 15 | 15,493,494 | – | SESN3 |

| AX-85147160 | 15 | 15,464,584 | – | SESN3 | |

| AX-85066093 | 3 | 14,263,986 | – | GPATCH4 | |

| SCA | AX-85115405 | 3 | 14,360,109 | – | IQGAP3 |

| AX-85098201 | 7 | 40,737,269 | – | COL23A1 | |

| AX-85077363 | 1 | 31,982,649 | – | CADM2 | |

| AX-85041155 | 1 | 31,452,080 | – | CADM2 | |

| AX-85178307 | 7 | 46,586,723 | – | FSTL4 | |

| TCA | AX-85178307 | 7 | 46,586,723 | – | FSTL4 |

| AX-85097354 | 16 | 59,785,310 | – | BRINP2 | |

| AX-85109602 | 28 | 32,271,813 | – | KCNMA1 | |

| AX-85092311 | 18 | 46,969,939 | TBCB | – | |

| AX-85115405 | 3 | 14,360,109 | – | MEF2D | |

| AX-85160204 | 6 | 74,395,035 | – | IGFBP7 | |

| AX-85115163 | 19 | 21,212,867 | – | NUFIP2 | |

| AX-85128429 | 3 | 8,311,409 | NDUFS2 | – | |

| AX-85127260 | 28 | 32,296,913 | – | KCNMA1 | |

| AX-85060416 | 12 | 3,071,256 | – | DIAPH3 | |

| NSC | AX-85122558 | 2 | 54,971,771 | – | KYNU |

| AX-85080363 | 20 | 48,102,049 | – | CDH10 | |

| AX-85149823 | 27 | 41,131,140 | – | THRB | |

| AX-85080722 | 2 | 55,117,009 | – | KYNU | |

| AX-85118378 | 27 | 37,743,905 | – | CSGALNACT1 | |

| AX-85069249 | 28 | 32,035,318 | – | ZNF503 | |

| AX-85069116 | 20 | 47,969,440 | – | CDH10 | |

| OD | AX-85166811 | 5 | 2,459,053 | – | TRHDE |

| AX-85107057 | 5 | 2,430,266 | – | TRHDE | |

| AX-85107924 | 5 | 2,493,145 | – | TRHDE | |

| AX-85078259 | 5 | 2,531,719 | – | TRHDE | |

| AX-85136537 | 5 | 2,378,071 | TRHDE | – | |

| AX-85092056 | 5 | 2,670,570 | – | TRHDE | |

| AX-85058327 | 4 | 89,251,931 | – | HYAL4 | |

| AX-85129886 | 5 | 5,220,162 | – | KRR1 | |

| AX-85080072 | 4 | 100,837,591 | – | MTPN | |

| CI | AX-85097797 | 10 | 69,031,255 | – | PELI2 |

| AX-85056150 | 12 | 70,335,740 | – | SOX21 | |

| AX-85091977 | 23 | 51,462,571 | – | GMDS | |

| AX-85082041 | 6 | 5,090,318 | – | PRDM5 | |

| AX-85127260 | 28 | 32,296,913 | – | KCNMA1 | |

| AX-85154020 | 3 | 56,690,373 | – | LMO4 |

FCA Age at first calving, SCA Age at second calving, TCA Age at third calving, CI Calving interval, NSC The number of artificial insemination, OD The open days. Chr and Position were obtained based on the cattle genome (Bos taurus UMD3.1 assembly)

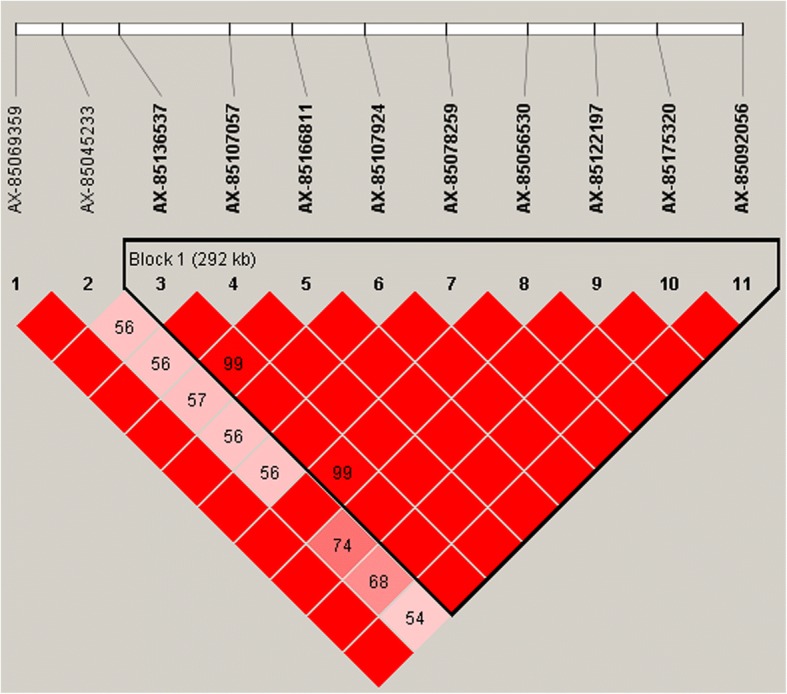

Linkage disequilibrium and haplotype associations

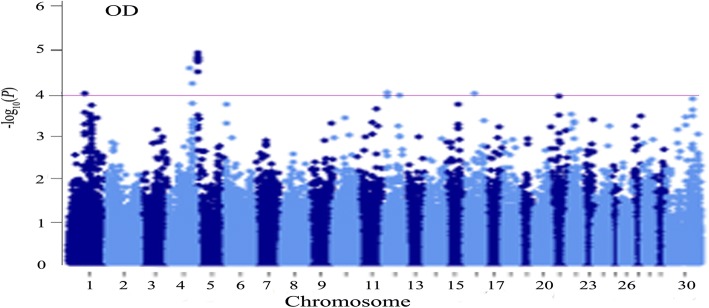

A particularly significant genomic region located at the equivalent 2.3–2.7 Mb of BTA5 (Bos taurus UMD 3.1 assembly), including six suggestive (P < 10− 4) SNPs, was identified to be associated with OD trait based on the GWAS results (Fig. 1). LD analysis indicated that a block (about 292 kb) was related to the above region (Fig. 2). Nine markers were in this block and they were in high LD, and most of them located in the TRHDE gene.

Fig. 1.

Manhattan plot for GWAS of open days in buffalo. OD, open days; x-axis, physical positions of SNPs by chromosome based on Bos taurus UMD3.1 genome assembly; y-axis, −log10 (P-values)

Fig. 2.

Linkage disequilibrium pattern for 11 SNPs, which have significant effects on OD by GWAS between 2 - 3Mbp on BTA5. Linkage disequilibrium block is presented in a triangle box based on LD (squared correlation coefficient, r2)

Four common haplotypes (CCGCATTAT, TTATGCCGC, TTATGCTAC, and CCGCACTAT) were inferred, and ten haplotype blocks were identified based on these four haplotypes. The analysis of relationship between haplotype blocks and buffalo reproductive traits revealed that haplotype blocks had significant effects on SCA (P < 0.05), CI (P < 0.001) and OD (P = 0.001). The multiple comparative analyses of the relationship between haplotype blocks and the three traits were shown in Additional file 1: Table S1, S2, and S3. The haplotype block (CCGCACTAT, TTATGCTAC) was associated with less second calving days, the haplotype block (CCGCATTAT, CCGCACTAT) was associated with the shortest calving interval, and the haplotype block (CCGCACTAT, CCGCACTAT) was associated with least open days.

Potential genes identified by combining RNA-seq with GWAS

According to the RNA-seq results, 25 of 28 genes identified by GWAS were found to be expressed in buffalo follicular GCs (Table 2). The highest expression was found in IGFBP7 during whole follicle growth in GCs, followed by NDUFS2, TBCB, MTPN, and GMDS. It is worth mentioning that the expression of the CSGALNACT1 gene decreased gradually with the increase in follicular diameter, and was differentially expressed (FDR < 0.05) between small and large follicles (< 5 mm and > 8 mm in diameter).

Table 2.

The expression level of genes associated with buffalo reproduction traits identified by GWAS during four stages of buffalo follicle growth

| Gene | Length (bp) | RPKM* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 5 mm | 5~ 8 mm | 8~ 12 mm | > 12 mm | ||

| IGFBP7 | 1107 | 723.49 | 840.17 | 965.37 | 883.67 |

| NDUFS2 | 1601 | 215.46 | 254.71 | 317.72 | 322.20 |

| TBCB | 994 | 76.32 | 75.14 | 81.12 | 93.92 |

| MTPN | 2844 | 28.63 | 67.29 | 40.74 | 15.93 |

| GMDS | 1845 | 27.68 | 23.66 | 36.08 | 33.39 |

| ZNF503 | 3514 | 21.09 | 20.43 | 25.47 | 15.84 |

| LMO4 | 5219 | 15.44 | 31.11 | 35.43 | 23.79 |

| GPATCH4 | 1830 | 10.96 | 8.31 | 8.36 | 9.72 |

| KRR1 | 1258 | 7.67 | 20.06 | 9.86 | 4.39 |

| MEF2D | 5716 | 7.62 | 10.25 | 10.50 | 11.03 |

| DIAPH3 | 4580 | 7.57 | 10.44 | 6.95 | 3.13 |

| NUFIP2 | 3406 | 7.41 | 12.83 | 6.21 | 4.13 |

| KYNU | 2273 | 4.20 | 4.49 | 7.27 | 4.51 |

| CSGALNACT1 # | 3199 | 3.53a | 0.87ab | 0.42b | 0.37b |

| IQGAP3 | 5860 | 3.51 | 4.93 | 3.85 | 1.71 |

| PRDM5 | 6373 | 3.38 | 3.92 | 2.40 | 1.66 |

| PELI2 | 5697 | 3.23 | 3.79 | 3.61 | 1.42 |

| SESN3 | 7235 | 2.14 | 5.73 | 2.46 | 1.42 |

| THRB | 6346 | 1.89 | 1.65 | 2.55 | 2.12 |

| CADM2 | 3342 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.04 | – |

| FSTL4 | 8110 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.12 |

| KCNMA1 | 2401 | 0.03 | 0.06 | – | – |

| COL23A1 | 2333 | – | – | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| SOX21 | 3417 | – | 0.02 | – | – |

| CDH10 | 3174 | – | 0.09 | – | 0.07 |

*RPKM Reads per kb per million reads. #CSGALNACT1: significanty differentially expressed gene (FDR < 0.05). The different superscript letters showed significant level

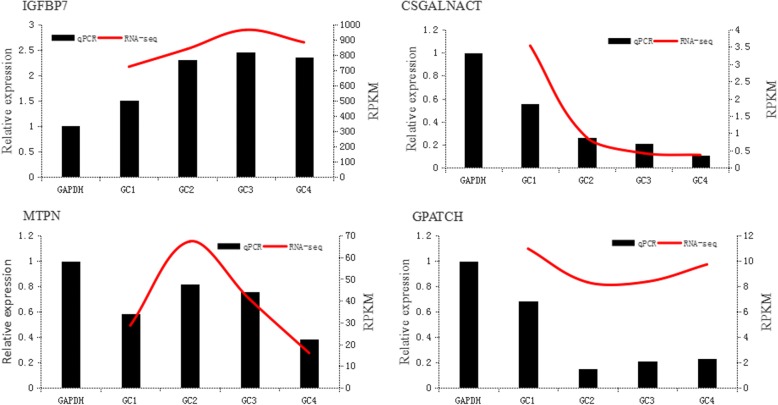

Four genes (IGFBP7, CSGALNACT, MTPN, and GPATCH) with high expression level according to RNA-seq were selected for q-PCR validation. The expression patterns of these selected genes at four stages obtained by q-PCR were basically consistent with RPKM values obtained by RNA-seq (Fig. 3). IGFBP7 was highly expressed during follicular development, so we chose this gene for subsequent functional verification.

Fig. 3.

Expression of selected genes mRNA in buffalo granulosa cells detected by q-PCR compared with RNA-seq

Knockdown of IGFBP7 affects cell growth

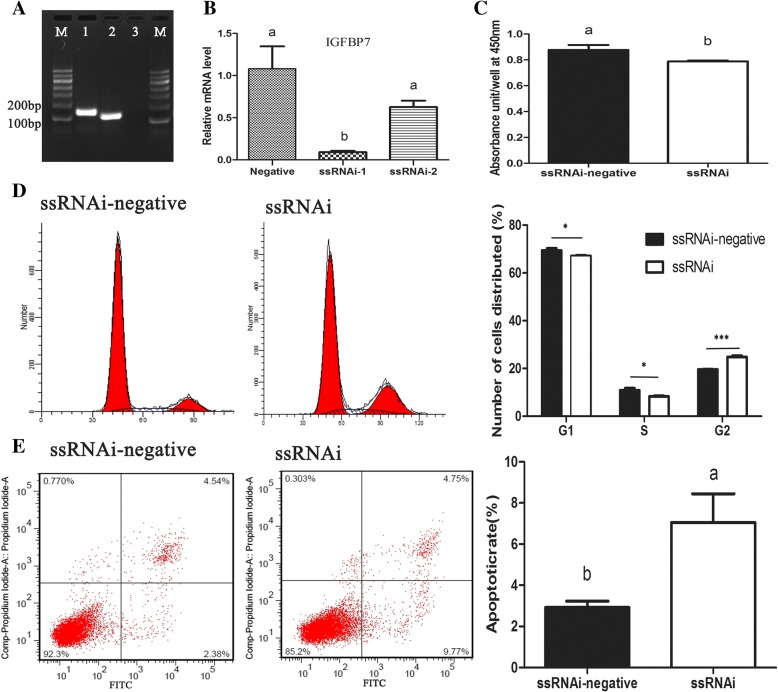

To investigate whether IGFBP7 plays a role in the development of buffalo GCs, two recombinant RNAi vectors were constructed. Both RNAi vectors were effective in knocking down IGFBP7 in buffalo GCs. The ssRNAi-1 vector had a better effect (98%) compared with ssRNAi-2 (Fig. 4b). Therefore, recombinant ssRNAi-1 vector was used for subsequent experiments.

Fig. 4.

Apoptosis, proliferation and cycle analysis of buffalo granulosa cells (GCs) after transfection with IGFBP7 ssRNAi. a Expression of IGFBP7in buffalo GCs detected by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Line 1 and 2 correspond to IGFBP7 and GADPH. b The mRNA expression level of IGFBP7 after transfection with IGFBP7 ssRNAi. c Analysis of buffalo GCs proliferation after knockdown of IGFBP7 with the absorbance at 450 nm. d and e showed analysis of cycles and apoptosis of buffalo granulosa cells after transfection with IGFBP7 ssRNAi, respectively. The values in each bar represents the mean ± SEM (n = 3). The different superscripts and the symbol of * on bars showed significant level (P < 0.05)

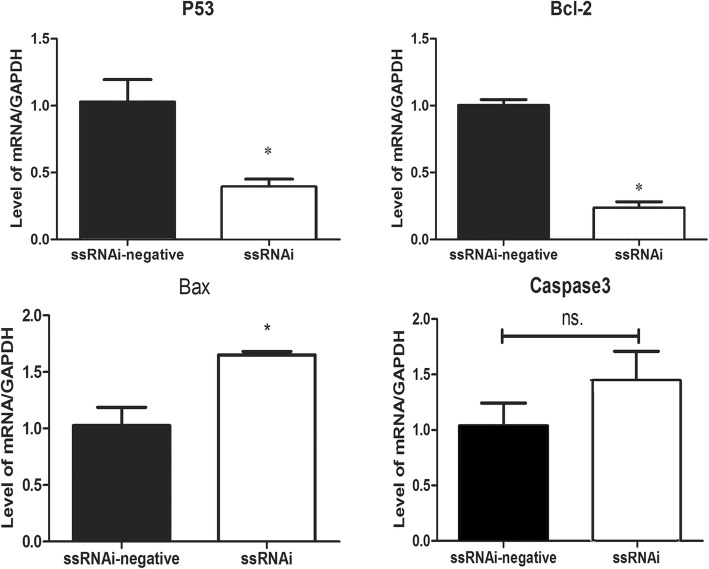

The knockdown of IGFBP7 led to the arrest of the cell cycle and the increase in the proportion of early apoptotic cells. The percentage of GCs in G2 phase was significantly (P < 0.05) increased and the portions of GCs in the G1 and S phase were decreased (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4d). The IGFBP7 silencing resulted in the significant increase in the number of apoptotic cells, compared with that of the control vector (7.5 ± 3.2 vs 2.9 ± 0.5, P = 0.003) (Fig. 4e). The results of apoptosis were also confirmed by detecting mRNA expression of BCL2, BAX, and CASPASE3 after IGFBP7 knockdown (Fig. 5). The knockdown of IGFBP7 also suppressed buffalo GCs proliferation. The absorbance at 450 nm in ssRNAi transfected cells was higher than that of control group (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 5.

Effects on different apoptotic factors after knockdown of IGFBP7 in buffalo GCs. The mRNA expression of each apoptotic related genes was presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). The symbol of * on bars showed significant level (P < 0.05). n.s. means none-significant

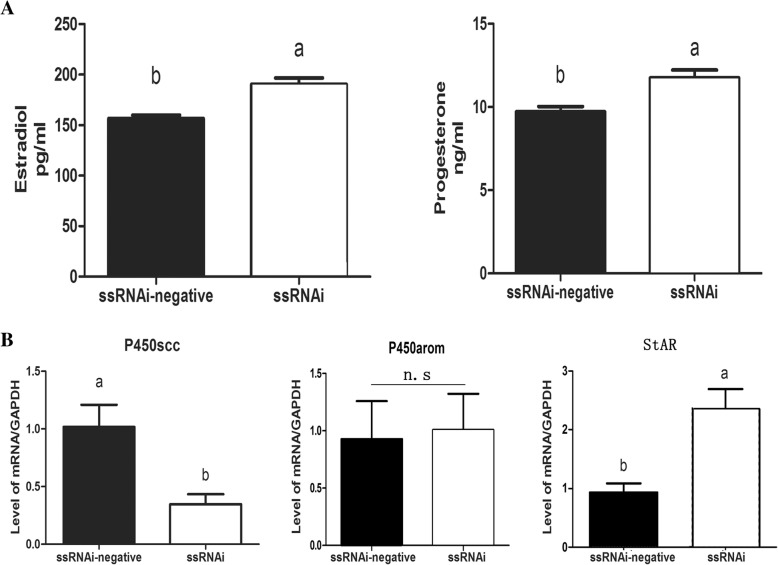

Knockdown of IGFBP7 increased basal progesterone and E2 production

The production of progesterone and E2 increased (P < 0.05) by knockdown of IGFBP7 in buffalo GCs cultured for 48 h after transfection (Fig. 6a). Furthermore, IGFBP7 silencing increased the mRNA expression of STAR and decreased the mRNA expression of CYP11A1 while no significant change in mRNA expression of CYP21A2 was observed (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

Production of progesterone and E2 and the expression level of related genes after knockdown of IGFBP7 in buffalo GCs. a Detection of progesterone and E2 secretion by ELISA Kit. b Analysis of mRNA expression level of hormone related genes. The values in each bar represents the mean ± SEM (n = 3). The different superscripts on bars showed significant level (P < 0.05). n.s. means none-significant

Discussion

In a previous study, 12 significant (P < 10− 4) SNPs associated with four reproductive traits were identified by GWAS in Murrah buffalo [4]. Nonetheless, these 12 significantly associated SNPs were not detected in the present study. Furthermore, a recent study showed more than 150 SNPs were associated with indicator traits of sexual precocity [19], however, none of them are identified in this study. Many reports indicated that GWAS has some limitations [20, 21], therefore, the functional verification analysis of significant SNPs detected by GWAS remains to be conducted. In a previous study, integrating sequence-based GWAS and RNA-seq provided novel insights into the genetic basis of mastitis and milk production in dairy cattle [10]. In the present study, we used GWAS to detect key genes associated with buffalo reproductive traits, and the results of RNA-seq were used to explore the changes in the expression of these key genes during the development of follicles. The expression of 25 out of 28 genes associated with buffalo reproductive traits was also detected in buffalo follicular GCs by RNA-seq, indicating that these genes may have affected the fertility by being directly through the regulation of buffalo follicle growth.

Hormones play an essential role in animal reproductive performance, and hormones and antibiotics have been applied as treatments in animal reproduction studies [22]. In the present study, five notable genes related to hormonal regulation were identified: TRHDE [23] for thyrotropin, KCNMA1 [24], TBCB [25] and CDH10 [26] for prostrate hormones, and THRB [27] for thyroid hormones. Thyroid dysfunction is associated with anovulation, abortion, and infertility in women and experimental animals [28]. Prostaglandin concentration is abnormally high in human ejaculates, and the prostate has specific dependence on androgen stimulation [29]. Thyroid hormones play a key role in seasonal cycles of body weight and reproduction [30]. Coincidentally, buffalo is also a seasonal estrus species. Furthermore, the mutation of THRB was reported to be significantly associated with thyroid hormone resistance (THR) [27]. KCNMA1 gene can enhance erectile strength and sexual behavior [31]. TRHDE encoding a thyrotropin releasing enzyme was reported to be associated with a variety of phenotypes including growth traits in Ujumqin sheep [23], the adaptation of goats to hot arid environments [32] and rheumatoid arthritis [33] in GWAS studies. According to the RNA-seq results, the expression of these hormone-related genes is low in buffalo granulosa cells, but we cannot ignore the impact of these genes because low levels of hormone may be highly effective in the regulation of follicle growth [34]. It is reasonable to assume that genes involved in hormonal regulation could be associated with buffalo fertility, and that these markers may have high utilization value for buffalo breeding.

Buffalo reproductive traits are controlled by polygenes, and many genes of small effects can produce synergistic effects on a pathway. Function based analysis can be used to detect the combined effects of these genes. In the present study, five important genes, NDUFS2, GMDS, KYNU, HYAL4, and CSGALNACT1, were classified into metabolic pathways. Metabolism is one of the most basic processes in the body, and plays a crucial role in ensuring the normal performance of various life activities. These genes may affect the reproductive performance of buffalo by regulating glucose, lipid, protein, and nucleic acid metabolism. Extensive information has previously been obtained about genes involved in metabolic pathways affecting animal fertility [35]. Among these genes, the CSGALNACT1 gene, which is required for normal cartilage development [36], was found to be significantly down-regulated by comparing buffalo follicles with diameter < 5 mm and > 8 mm in the present study. Based on it, we hypothesize that CSGALNACT1 gene has effect on the growth of buffalo follicles by changing the level of expression to regulate glucose metabolism.

In our previous study, CADM2 (cell adhesion molecule 2) was found to be associated with buffalo reproductive performance by using the BovineSNP50 BeadChip [3]. One SNP located at about 143 kb of the upstream bovine CADM2 was associated with days from first calving to conception and calving interval in days from first to second calving. In the present study, another SNP AX-85077363 located downstream of the bovine CADM2 gene was identified to be associated with SCA trait. However, the expression of CADM2 was only detected in early follicular GCs. We speculate that the two sites nearby the CADM2 gene may interact with other significant SNPs or genes to influence buffalo reproductive performance.

ZNF503, KRR1, and MTPN are other target genes associated with buffalo reproductive traits identified in this study. ZNF503, also known as Nolz-1, which promotes mammary epithelial cell proliferation and enhances cell invasion [37], plays an important role in embryogenesis [38]. KRR1 was reported to be associated with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in European cohorts [39]. MTPN plays an essential role in cell and skeletal muscle growth [40], and it is related to antigen recognition which is a key process in immune response [41]. These three genes were highly expressed in buffalo GCs with follicular diameter 5 ~ 12 mm, suggesting that they may have participated in dominant follicle selection.

IGFBP7 shares sequence homology with follistatin [42] which is originally considered as an inhibitor of FSH secretion [43, 44] and plays a crucial role in folliculogenesis and ovarian function [45, 46]. The expression of IGFBP7 was also identified in the GCs of the large antral follicles of porcine ovary [47] and bovine corpus luteum [48]. Therefore, we speculate that IGFBP7 may participate in the regulation of follicle development and ovulation. In the present study, our RNA-seq results showed that IGFBP7 is highly expressed in GCs of buffalo antral follicles. Moreover, the knockdown of IGFBP7 in buffalo GCs affected the number of apoptotic cells, cell cycles, cell proliferation, and the production of estrogen and progesterone. These observations indicate that IGFBP7 may be involved in the regulation of follicle development.

Conclusions

This is the first attempt combining GWAS and RNA-seq to explore genetic mechanism of buffalo reproductive performance. A total of 25 important genes were identified to be associated with buffalo reproductive performance, and they may affect the buffalo reproductive traits through the regulation of follicle development. The study expands the knowledge of the genetic basis of buffalo fertility, and it may also benefit future research on improving buffalo breeding programs.

Materials and methods

Animal and data collection

The data and samples used for GWAS were obtained from the Italian Buffalo Breeders Association, which is responsible for the buffalo production program in Italy.

The data analysis was based on 1424 lactations of 462 Italian Mediterranean buffaloes born in 2000–2011 in four Italian farms. Six reproductive traits were examined including first calving age (FCA), second calving age (SCA), third calving age (TCA), calving interval (CI), number of services per conception (NSC), and open days (OD).

The trait FCA is defined as the days from the birth to first calving of the buffalo; SCA is defined as the days from birth to second calving of the buffalo; and the days between the third calving and the birth of buffalo is defined as TCA. The CI is defined as the days between consecutive events. The trait NSC refers to the times of artificial insemination (AI) that is required for each buffalo to conceive. The OD is defined as the days from calving to the next conception.

Data structure is important as they underpin GWAS results. The descriptive statistics of phenotypes of buffalo reproductive traits are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of studied reproduction traits

| Traits | Records | Mean | SD | Max | Min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCA | 483 | 1015.44 | 157.08 | 1769 | 574 |

| SCA | 398 | 1491.70 | 208.64 | 2317 | 797 |

| TCA | 230 | 1908.86 | 255.79 | 3071 | 1185 |

| CI | 891 | 431.55 | 75.67 | 657 | 235 |

| NSC | 1110 | 2.27 | 0.68 | 6 | 1 |

| OD | 1008 | 120.04 | 61.58 | 270 | 40 |

SD Standard deviation, FCA Age at first calving, SCA Age at second calving, TCA Age at third calving, CI Calving interval, NSC The number of artificial insemination, OD Open days

Genotyping and quality control

Genomic DNA was isolated from the blood leucocytes of Italian buffalo using a standard phenol-chloroform extraction protocol and the DNA was genotyped using the 90 K Axiom Buffalo SNP Array at Delta Genomics (Edmonton AB, Canada). Sample quality control used animal call rates > 97%. For single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), thresholds were set as SNPs call rates > 95%, minor allele frequency (MAF) > 0.05 and Hardy - Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) test P-value < 10− 6. Unmapped SNPs were eliminated and markers present on the Y chromosome were removed. After quality control, 62,747 SNPs and 462 buffaloes were used for subsequent analyses.

Genome wide association study

The association study was performed using a ridge regression BLUP (rrBLUP) model in both PLINK and R software.

Where y is the vector of reproductive traits, X is a vector of coded SNP genotypes, which is assigned to − 1, 0, or 1 for genotypes AA, AB, and BB, respectively. Β is the SNP effect; u is the vector of the polygenic effects, and e is the vector of random residuals. u and e are assumed to be subject to the normal distribution, [u ~(0,Kσu2)] and [e ~ (0, Iσe2)], where K is the genomic relationship matrix based on pedigree information, σu2 is the genetic variance, I is an identify matrix, σe2 is the residual variance. The number of potential markers was too small after Bonferroni correction (0.05/62747 = 7.97 × 10− 7), resulting in very low statistical power. Therefore, we used suggestive P value (P < 0.0001) as the threshold in this analysis.

Haplotype analyses

The linkage disequilibrium (LD) between markers was calculated as squared correlation coefficient (r2) of alleles using Haploview 4.2 software. The distances of pairwise SNPs less than 500 kb were used to draw the LD figure. Haplotype blocks were constructed by using PHASE software, and the association between each haplotype block and six reproductive traits were estimated with Bonferroni t test in R. We used suggestive P value (P < 0.05) as threshold for considering candidate haplotype blocks affecting buffalo reproductive traits.

Identification of SNP location

Two available buffalo genome sequences on the NCBI platform are not displayed on chromosomes and genes are not annotated (UMD CASPUR WB 2.0; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly/GCF_000471725.1/). Cattle and buffalo have been reported to be closely related, sharing homology in chromosome banding and gene mapping [49, 50]. It has also been confirmed that the bovine genome is a useful source of markers for buffalo genome mapping [51, 52], three available buffalo GWAS were constructed using the cattle genome reference [4, 18, 53]. In the present study, the SNP location was identified using the cattle genome sequence.

Gene expression in buffalo follicular GCs

The normal development of follicles directly affects buffalo reproductive performance. We speculated that key genes associated with reproductive performance identified by GWAS may be involved in the regulation of follicular development. Therefore, we integrated GWAS results with our previous RNA-seq results [9] to explore the expression of key genes in buffalo GCs during follicular development. The expressions of significant genes identified by GWAS were obtained by RNA-seq.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (q-PCR) validation

Ovaries were collected from a local abattoir in Wuhan, China, from nonpregnant buffaloes. The ovaries with lutealized and large cystic follicles were detected and discarded. The largest follicles from normal ovaries were collected. Follicles were graded into 4 categories according to their diameters, namely, diameter < 5 mm, 5 ~ 8 mm, 8 ~ 12 mm and > 12 mm, and morphological appearance was used to assess the developmental stages of the follicles. GCs were collected from the follicles after grading and each category included 10 follicles. Single-stranded cDNA was obtained from 1 μg total RNA isolated from each of the groups. Primers (Additional file 1: Table S4) for q-PCR were designed using Primer Premier 5.0 software and synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanhai) Co. Ltd. q-PCR was performed on LightCycler 480II (Roche), using a SYBR Green-based PCR assay. A reaction system consists of a small aliquot of the cDNA (100 ng), 10 μL PCR master mix (TaKaRa, Japan), 2 μL of primers (1 μL of each forward and reverse primer, 10 pmol/μL), and 7 μL ddH2O. The q-PCR was run as follows: 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, annealing temperatures for 30 s (the annealing temperature for each gene was shown in Additional file 1: Table S4), and 72 °C for 30 s in 96-well optical reaction plate. The expression levels of the tested genes were determined by CT values and the final expression for each gene was normalized against the value of GAPDH. The analyses were conducted with three biological replicates.

Functional verification by RNA interference technique.

Isolation and culture of buffalo granulosa cells were described in our previous study [54]. Two ssRNAi vectors (Additional file 1: Table S5) of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 (IGFBP7) were constructed according to the coding sequence (Accession number: XM_006058372). These two plasmids and another negative control plasmid were named ssRNAi-1, ssRNAi-2, and ssRNAi-negative, respectively. The method of transfection was described in our previous study [54].

After transfection with plasmid, the mRNA expression of IGFBP7, apoptosis related genes, and hormone synthesis related genes were detected by q-PCR which was described above. AnnexinV-FITC/PI kit (KGA107, Kaiji Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) was used to measure the apoptosis of GCs according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cell cycle detection was also performed using flow cytometry and the excitation wavelength was 488 nm according to the manufacturer’s protocol of cell cycle detection kit (KGA512, Kaiji Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China). The analysis of cell proliferation was performed using the Cell Counting Kit (catalogue number: ck04) with absorbance wavelength being 450 nm. Moreover, the cell culture medium was collected and the production of estrogen and progesterone was measured using a Bovine ELISA Kit (catalogue number: JYM0045Bo and JYM0056Bo, respectively) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Additional file

Table S1. Multiple Comparative Analysis of the relationship between Buffalo Haplotype block and SCA Trait. Table S2. Multiple Comparative Analysis of the relationship between Buffalo Haplotype block and CI Trait. Table S3. Multiple Comparative Analysis of the relationship between Buffalo Haplotype block and OD Trait. Table S4. Primers used for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Table S5. siRNA description. (DOC 64 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the field staff and other participants in our study.

Funding

This work financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31772602 and 31772604) and the earmarked fund for Modern Agro-industry Technology Research System (CARS-37-04B).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CI

Calving interval

- FCA

First calving age

- GC

Granulosa cell

- GWAS

Genome-wide association study

- HWE

Hardy - Weinberg equilibrium

- LD

Linkage disequilibrium

- MAF

Minor allele frequency

- NGS

Next generation sequencing

- NSC

Number of services per conception

- OD

Open days

- q-PCR

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- SCA

Second calving age

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- TCA

Third calving age

Authors’ contributions

J Li carried out most data analysis and gene verification experiments, and drafted the manuscript. J Liu performed the genome SNP scans and genotype analysis. GC contributed to sample preparation and collection of reproductive trait records. GP contributed to analysis of data, and assisted in revising manuscript. CZ helped to interpret the raw data and revise manuscript. ZW contributed to genotype analysis and revise manuscript. CM assisted in critical revisions of manuscript. BG contributed to collection of reproductive trait records, and assisted in critical revisions of manuscript. AS contributed to sample preparation. GH assisted in revising manuscript. AL contributed to sample preparation, experimental design and data analysis, and assisted in writing and revising manuscript. LY contributed to design the experiments and coordinate the project, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval

The Scientific Ethics Committee of Huazhong Agricultural University approved the experimental design and animal treatments for the present study (permit number HZAUBU-2015-007), and all experimental protocols were conducted in accordance with the guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jun Li, Email: huosu2014@163.com.

Jiajia Liu, Email: jjl1223@126.com.

Giuseppe Campanile, Email: giucampa@unina.it.

Graham Plastow, Email: plastow@ualberta.ca.

Chunyan Zhang, Email: chunyan3@ualberta.ca.

Zhiquan Wang, Email: zhiquan.w@gmail.com.

Martino Cassandro, Email: martino.cassandro@unipd.it.

Bianca Gasparrini, Email: bgasparr@unina.it.

Angela Salzano, Email: Angela.salzano@unina.it.

Guohua Hua, Email: huaguohua09@gmail.com.

Aixin Liang, Email: lax.pipi@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Liguo Yang, Email: liguoyang2006@163.com.

References

- 1.Jiang L, Liu J, Sun D, Ma P, Ding X, Yu Y, Zhang Q. Genome wide association studies for milk production traits in Chinese Holstein population. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goddard ME, Hayes BJ. Mapping genes for complex traits in domestic animals and their use in breeding programmes. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(6):381–391. doi: 10.1038/nrg2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song LJ, Wu JF, Yang Guo L, Zhang SJ, Wu JJ. Investigation of transferability of BovineSNP50 BeadChip from cattle to;water buffalo for genome wide association study. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40(2):743–750. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2175-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Camargo GM, Aspilcueta-Borquis RR, Fortes MR, Porto-Neto R, Cardoso DF, Santos DJ, Lehnert SA, Reverter A, Moore SS, Tonhati H. Prospecting major genes in dairy buffaloes. BMC Genomics. 2015;16(1):872. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1986-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leiserson MD, Eldridge JV, Ramachandran S, Raphael BJ. Network analysis of GWAS data. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2013;23(6):602–610. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Musunuru K, Strong A, Frank-Kamenetsky M, Lee NE, Ahfeldt T, Sachs KV, Li X, Li H, Kuperwasser N, Ruda VM. From noncoding variant to phenotype via SORT1 at the 1p13 cholesterol locus. Nature. 2010;466(7307):714–719. doi: 10.1038/nature09266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lappalainen T, Sammeth M, Friedlander MR, t Hoen PA, Monlong J, Rivas MA, Gonzalez-Porta M, Kurbatova N, Griebel T, Ferreira PG, et al. Transcriptome and genome sequencing uncovers functional variation in humans. Nature. 2013;501(7468):506–511. doi: 10.1038/nature12531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sirard MA, Fournier É, Dufort I, Gilbert I, Robert C. 77 Transcriptome profiling in oocytes-embryo and granulosa cells from bovine. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2016;29(1):146–146.

- 9.Li J, Li Z, Liu S, Zia R, Liang A, Yang L. Transcriptome studies of granulosa cells at different stages of ovarian follicular development in buffalo. Anim Reprod Sci. 2017;187:181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang L, Sahana G, Su G, Yu Y, Zhang S, Lund MS, Sã Rensen P. Integrating sequence-based GWAS and RNA-Seq provides novel insights into the genetic basis of mastitis and Milk production in dairy cattle. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45560. doi: 10.1038/srep45560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calabrese Gina M., Mesner Larry D., Stains Joseph P., Tommasini Steven M., Horowitz Mark C., Rosen Clifford J., Farber Charles R. Integrating GWAS and Co-expression Network Data Identifies Bone Mineral Density Genes SPTBN1 and MARK3 and an Osteoblast Functional Module. Cell Systems. 2017;4(1):46-59.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calabrese G, Bennett BJ, Orozco L, Kang HM, Eskin E, Dombret C, De Backer O, Lusis AJ, Farber CR. Systems genetic analysis of osteoblast-lineage cells. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(12):e1003150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J, Liu X, Yang J, Wang H, Jiang J, Liu L, He S, Ding X, Liu J, Zhang Q. Targeted resequencing of GWAS loci reveals novel genetic variants for milk production traits. BMC Genomics. 2014;15(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao H, Qi YU. Primordial follicle assembly and development. J Reprod Med. 2007;16(6):453–456.

- 15.Ginther OJ, Beg MA, Donadeu FX, Bergfelt DR. Mechanism of follicle deviation in monovular farm species. Anim Reprod Sci. 2003;78(3–4):239–257. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4320(03)00093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Austin EJ, Mihm M, Ryan MP, Williams DH, Roche JF. Effect of duration of dominance of the ovulatory follicle on onset of estrus and fertility in heifers. J Anim Sci. 1999;77(8):2219–2226. doi: 10.2527/1999.7782219x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scaramuzzi RJ, Baird DT, Campbell BK, Driancourt MA, Dupont J, Fortune JE, Gilchrist RB, Martin GB, McNatty KP, McNeilly AS, et al. Regulation of folliculogenesis and the determination of ovulation rate in ruminants. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2011;23(3):444–467. doi: 10.1071/RD09161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu JJ, Liang AX, Campanile G, Plastow G, Zhang C, Wang Z, Salzano A, Gasparrini B, Cassandro M, Yang LG. Genome-wide association studies to identify quantitative trait loci affecting milk production traits in water buffalo. J Dairy Sci. 2018;101(1):433–444. doi: 10.3168/jds.2017-13246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Natalia I, Bermal CR, Nascimento TAP, Braga MAF, Oliveira SRMD, Mortati DM, Braga BA, Fernando B, Roberto C. Genome-wide association study for Indicator traits of sexual precocity in Nellore cattle. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0159502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearson Thomas A. How to Interpret a Genome-wide Association Study. JAMA. 2008;299(11):1335. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.11.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCarthy MI, Hirschhorn JN. Genome-wide association studies: potential next steps on a genetic journey. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(R2):R156–R165. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Refsdal AO. To treat or not to treat: a proper use of hormones and antibiotics. Anim Reprod Sci. 2000;60(60–61):109–119. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4320(00)00094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Z, Ma X, Xuan J, Wang H, Yuan Z, Wu M, Liu R, Zhu C, Wei C, Zhao F. Identification of MEF2B and TRHDE gene polymorphisms related to growth traits in a new Ujumqin sheep population. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khaitan D, Sankpal UT, Weksler B, Meister EA, Romero IA, Couraud PO, Ningaraj SN. Role of KCNMA1 gene in breast cancer invasion and metastasis to brain. BMC Cancer. 2009;9(1):258. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng L, Zhang SD, Yuen HF, Mccrudden CM, Wen Q, Chan KW, Hang FK. Identification of TWIST-interacting genes in prostate cancer. Sci China Life Sci. 2017;60(4):386–396. doi: 10.1007/s11427-016-0262-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.An CH, Je EM, Yoo NJ, Lee SH. Frameshift mutations of cadherin genes DCHS2, CDH10 and CDH24 genes in gastric and colorectal cancers with high microsatellite instability. Pathol Oncol Res. 2015;21(1):181–185. doi: 10.1007/s12253-014-9804-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Işık E, Beck PP, Campi I, Özon A, Alikaşifoğlu A, Gönç N, Kandemir N. Thyroid hormone resistance: a novel mutation in thyroid hormone receptor beta (THRB) gene - case report. Turk J Pediatr. 2013;55(3):322–7. [PubMed]

- 28.Rodriguez-Castelãn J, Anaya-Hernãndez A, Mendez-Tepepa M, Martinez-Gomez M, Castelãn F, Cuevas-Romero E. Distribution of thyroid hormone and thyrotropin receptors in reproductive tissues of adult female rabbits. Endocr Res Commun. 2016;42(1):59–70. doi: 10.1080/07435800.2016.1182185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mann T. Secretory function of the prostate, seminal vesicle and other male accessory organs of reproduction. J Reprod Fertil. 1974;37(1):179–188. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0370179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barrett P, Ebling FJP, Schuhler S, Wilson D, Ross AW, Warner A, Jethwa P, Boelen A, Visser TJ, Ozanne DM. Hypothalamic thyroid hormone catabolism acts as a gatekeeper for the seasonal control of body weight and reproduction. Endocrinology. 2007;148(8):3608–3617. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christ GJ, Andersson KE, Williams K, Zhao W, D'Agostino R, Jr, Kaplan J, Aboushwareb T, Yoo J, Calenda G, Davies KP, et al. Smooth-muscle-specific gene transfer with the human maxi-k channel improves erectile function and enhances sexual behavior in atherosclerotic cynomolgus monkeys. Eur Urol. 2009;56(6):1055–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim ES, Elbeltagy AR, Aboul-Naga AM, Rischkowsky B, Sayre B, Mwacharo JM, Rothschild MF. Multiple genomic signatures of selection in goats and sheep indigenous to a hot arid environment. Heredity (Edinb) 2016;116(3):255–264. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2015.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freudenberg Jan, Lee Hye-Soon, Han Bok-Ghee, Shin Hyoung Do, Kang Young Mo, Sung Yoon-Kyoung, Shim Seung-Cheol, Choi Chan-Bum, Lee Annette T., Gregersen Peter K., Bae Sang-Cheol. Genome-wide association study of rheumatoid arthritis in Koreans: Population-specific loci as well as overlap with European susceptibility loci. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2011;63(4):884–893. doi: 10.1002/art.30235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gibbons John R., Wiltbank Milo C., Ginther O.J. Relationship between Follicular Development and the Decline in the Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Surge in Heifers. Biology of Reproduction. 1999;60(1):72–77. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod60.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morfeld Kari A., Brown Janine L. Ovarian acyclicity in zoo African elephants (Loxodonta africana) is associated with high body condition scores and elevated serum insulin and leptin. Reproduction, Fertility and Development. 2016;28(5):640. doi: 10.1071/RD14140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watanabe Y, Takeuchi K, Onaga SH, Sato M, Tsujita M, Abe M, Natsume R, Li M, Furuichi T, Saeki M. Chondroitin sulfate N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-1 is required for normal cartilage development. Biochem J. 2010;432(Pt 1):47–55. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shahi P, Slorach EM, Wang CY, Chou J, Lu A, Ruderisch A, Werb Z. The transcriptional repressor ZNF503/Zeppo2 promotes mammary epithelial cell proliferation and enhances cell invasion. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(6):3803–3813. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.611202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang SL, Liu YC, Chen SY, Huang TH, Liu PT, Liu FC. Identification of two evolutionarily conserved 5′ cis-elements involved in regulating spatiotemporal expression of Nolz-1 during mouse embryogenesis. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Day FR, Hinds DA, Tung JY, Stolk L, Styrkarsdottir U, Saxena R, Bjonnes A, Broer L, Dunger DB, Halldorsson BV, et al. Causal mechanisms and balancing selection inferred from genetic associations with polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8464. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Makina SO, Muchadeyi FC, van Marle-Koster E, Taylor JF, Makgahlela ML, Maiwashe A. Genome-wide scan for selection signatures in six cattle breeds in South Africa. Genet Sel Evol. 2015;47(1):92. doi: 10.1186/s12711-015-0173-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang L, Wang Y. Molecular characterization, expression patterns and subcellular localization of Myotrophin (MTPN) gene in porcine skeletal muscle. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39(3):2733–2738. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kato MV. A secreted tumor-suppressor, mac25, with activin-binding activity. Mol Med. 2000;6(2):126–135. doi: 10.1007/BF03401780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ueno N, Ling N, Ying SY, Esch F, Shimasaki S, Guillemin R. Isolation and partial characterization of follistatin: a single-chain Mr 35,000 monomeric protein that inhibits the release of follicle-stimulating hormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84(23):8282–8286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.23.8282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robertson DM, Klein R, de Vos FL, Mclachlan RI, Wettenhall RE, Hearn MT, Burger HG, de Kretser DM. The isolation of polypeptides with FSH suppressing activity from bovine follicular fluid which are structurally different to inhibin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;149(2):744–749. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(87)90430-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jorgez CJ, Klysik M, Jamin SP, Behringer RR, Matzuk MM. Granulosa cell-specific inactivation of follistatin causes female fertility defects. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18(4):953–967. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muttukrishna S, Tannetta D, Groome N, Sargent I. Activin and follistatin in female reproduction. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;225(1–2):45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wandji S.-A. Messenger Ribonucleic Acids for MAC25 and Connective Tissue Growth Factor (CTGF) Are Inversely Regulated during Folliculogenesis and Early Luteogenesis. Endocrinology. 2000;141(7):2648–2657. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.7.7576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Casey OM, Fitzpatrick R, Mcinerney JO, Morris DG, Powell R, Sreenan JM. Analysis of gene expression in the bovine corpus luteum through generation and characterisation of 960 ESTs. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Struct Expr. 2004;1679(1):10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meo GPD, Perucatti A, Schibler L, Incarnato D, Ferrara L, Cribiu EP, Iannuzzi L. Thirteen type I loci from HSA4q, HSA6p, HSA7q and HSA12q were comparatively FISH-mapped in four river buffalo and sheep chromosomes. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2000;90(1–2):102–105. doi: 10.1159/000015642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Di MG, Perucatti A, Uboldi C, Roperto S, Incarnato D, Roperto F, Williams J, Eggen A, Ferretti L, Iannuzzi L. Comparative mapping of the fragile histidine triad (FHIT) gene in cattle, river buffalo, sheep and goat by FISH and assignment to BTA22 by RH-mapping: a comparison with HSA3. Anim Genet. 2005;36(4):363–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2005.01319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ianella P, Venancio LP, Stafuzza NB, Miziara MN, Agarwala R, Schäffer AA, Riggs PK, Womack JE, Amaral ME. First radiation hybrid map of the river buffalo X chromosome (BBUX) and comparison with BTAX. Anim Genet. 2010;39(2):196–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2007.01696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tantia MS, Galvão SR, Caetano AR, Paola M, Miziara MN, Aravind KM, Boby M, Pardha SG, Satish K, Aparna P. A first generation whole genome RH map of the river buffalo with comparison to domestic cattle. BMC Genomics. 2008;9(1):631. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.El-Halawany N, Abdel-Shafy H, Shawky AEMA, Abdel-Latif MA, Al-Tohamy AFM, El-Moneim OMA. Genome-wide association study for milk production in Egyptian buffalo. Int Symp Anim Funct Gen. 2017;2017:10–16. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Riaz H, Dong P, Shahzad M, Yang L. Constitutive and follicle-stimulating hormone-induced action of somatostatin receptor-2 on regulation of apoptosis and steroidogenesis in bovine granulosa cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;141(1):150–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Multiple Comparative Analysis of the relationship between Buffalo Haplotype block and SCA Trait. Table S2. Multiple Comparative Analysis of the relationship between Buffalo Haplotype block and CI Trait. Table S3. Multiple Comparative Analysis of the relationship between Buffalo Haplotype block and OD Trait. Table S4. Primers used for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Table S5. siRNA description. (DOC 64 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.