Abstract

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy was used to analyze the changes of secondary structure of myofibrillar proteins in short-term storage of battered and deep-fried pork slices. These changes were combined with low-field NMR analysis results to analyze the correlation between secondary structure and dynamic changes of water content. The results showed that the number of α-helix and β-sheet decreased by 22.90 and 16.54% respectively, and the orderly structure changed to the disorder structure. The correlation results show that NMR spin–spin relaxation time (T21) has a high negative correlation with α-helix, β-sheet, and has a high positive correlation with irregular curl and β-turn. The population of immobile water (P22) has a very high positive correlation with α-helix, β-sheet, and has a relatively high negative correlation with irregular curl and β-turn. The immobilized water plays an important role in maintaining the secondary structure.

Keywords: FTIR, LF-NMR, Secondary structure, Correlation analysis

Introduction

FTIR is a rapid, sensitive and non-waste generating technique that can be widely used in the detection of small molecules, complexes, cell and tissue analysis (Berthomieu and Hienerwadel, 2009). Over the past few decades, FTIR has been considered as an effective tool for the analysis of food chemistry. It has been used to analyze food ingredients (Jung, 2008), meat processing (Zając et al., 2017), identification of protein types and functions (Ishiguro et al., 2006), and so on. Fourier is also a powerful tool for protein secondary structure analysis.

Currently, some researchers applied low-field NMR (LF-NMR) to analyze the dynamic distribution of moisture. Some have done T2 relaxation time and water-related researches (Hullberg and Bertram, 2005; Renou et al., 2003). These studies were mainly on the dryness of meat products (Sørland et al., 2004), the composition of meat (Aursand, 2009), the quality of pork processing (Li et al., 2012), and the effect of fatty acids on moisture distribution during cooked (Miklos et al., 2014). However, quantitative determination for water states by LF-NMR is still not published. The industrialization of traditional food is an important in modern food industry, in which cooked meat products is as a fundamental and important component. Nevertheless, the changes in protein structure in cooked meat during storage were still not explored in depth. Meersman et al. (2002) studied the changes of myoglobin spatial structure. Promeyrat et al. (2010) evaluated protein aggregation in cooked meat.

Battered and deep-fried pork slices (BFS) is a traditional Chinese food. Rapidly decrease of meat tenderness caused by the loss of moisture and protein denaturation during storage was the main limiting factor for its industrialization. Denatured of protein may affect the state of the binding moisture, therefore change the tenderness of meat. There is a correlation between dynamic distribution of moisture and the protein structure. The loss of moisture affects the spatial structure of the protein (Zhiyun et al., 2006). At present, there are almost no relevant studies about protein structure changes by using the correlation between the dynamic distribution of moisture and protein structure in the cooked meat. In this work, the dynamic changes of moisture and the protein secondary structures during the process of storage were analyzed in detail. In this way, it helps to understand the mechanism of meat tenderness reduction during storage process. In turn, the edible period of traditional food BAF can be extended.

Materials and methods

Material

Starch, food grade, Heilongjiang Ruyi Starch Food Co., Ltd; Corn Germ Oil, food grade, Shanghai Kerry Food Industry Co., Ltd; Fresh pork tenderloin purchased from Beijing Hualian Supermarket; NaCl, analytical pure, Tianjin Kemiou Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd; EGTA, analytical pure, Biotechnology (Shanghai) Co., Ltd; HCl, analytical pure, Tianjin DaMao Chemical Reagent Factory; MgCl2, analytical pure, Tianjin Damao Chemical Reagent Factory.

Equipment

NM120-Analyst Shanghai New Mai Electronics Technology Co., Ltd; VD53 Vacuum Drying Box Germany Binder Company; DH-2000R High Speed Refrigerated Centrifuge Shanghai Deyang Yibang Instrument Co., Ltd; Frontier FT-IR Spectrometer Perkin Elmer, USA.; EF-101 type stainless steel single-cylinder electric blast furnace, China Ltd, Guangzhou, China.

BFS slices preparation

The preparation process of BFS slices is based on the method of Guo et al. (2016) with a slight modification. Pork tenderloin samples were cut into 5 mm in thickness and 8 cm square slices, mixed well with starch for further frying. Frying was carried out with a laboratory scale deep-fat fryer with electronic temperature controller. Corn germ oil was renewed every day. Battered pork slices were fried at 170 ± 2 °C for 150 s, then the fried samples were strained for 1 min to remove surface oil.

Sample extraction

The prepared 1000 g BFS was de-paste and was randomly divided into groups of 200 g each, store at 0–40 °C for 12 h, sampling once every 2 h. When sampling, use a sampler with a diameter of 2.0 cm on each BFS to take an average of three points on the diagonal. After the samples were taken, they were removed the paste from the outside and mixed until ready for use. Each level was repeated five times.

MP preparation

MP was prepared according to the method of Park et al. (2007) with slightly modification. Protein concentration of the myofibril pellet was measured by the procedure reported by Biuret (Kong et al., 2013), which used bovine serum albumin as the standard. The purified MP isolate was stored in a tightly capped bottle at − 20 °C, and are analysed within 1 day.

Preparation of sample for FTIR

The prepared MP was dissolved in phosphate buffer of 10 mmoL/L (pH 7), after stored for 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 h, make the protein final mass volume fraction 2%. The protein solution was placed in 6 cm dish pre-frozen at − 80 °C 4 h, Then placed in a freeze dryer dehydration, resulting myofibril freeze-dried protein powder stored at 0–40 °C for 12 h. The MP stored for 0 h after just frying were used as blank controls.

Data processing

The scanning range of FTIR is 4000–400 cm−1 with a resolution of 1 cm−1. The S/N ratio is 180,000:1 (dB).The amide I band of the infrared spectrum of the reaction system was processed by second-order derivative, Fourier self-deconvolution and spectral line fitting to deduce the change of protein secondary structure. Protein structures were analyzed by infrared spectroscopy according to Byler method (Gerasimowicz et al., 1986). The peak at 1600–1700 cm−1, belonging to the amide I band absorption peak, was analyzed by Peak Fit 4.12 software. After correcting the baseline and deconvolution, the second derivative fit until the residual was minimal. The percentage was calculated on the secondary structure of each sub-peak area. Repeat three times for each level.

LF-NMR

Operating parameters were set as following, Magnet temperature 32 °C, proton resonance frequency 22.3 MHz, the value of τ (the time between the 90° pulse and the 180° pulse) 200 μs, the analog gain 20, the repetition interval TW 1800 ms. The S/N ratio is 40:1 (dB). Lateral relaxation time T2 was measured using the CPMG sequence. The resulting exponential decay pattern was inverted using the NMR analysis application software from Shanghai Newmark Electronic Technology Co. Ltd. The discrete and continuous type of T2 spectrum, and the corresponding data was used for analyzed by SAS9.01 (SAS USA). Repeat five times for each level.

Results and discussion

Dynamic analysis of water content by LF-NMR

The T2 relaxation time and peak area of MP in the BFS are shown in the Table 1. Under different temperature conditions, T22 has the longest relaxation time of 82.61–101.83 ms and P2 results showed that P22 is the highest from 87.17 to 89.18%. This indicated that the main form of water in BFS was immobilized water. It can be seen that the relative moisture content of deep-bound water (P21) in the meat samples did not change significantly with storage temperature (Table 1). P21 was related to the structure of MP. The size of P21 mainly was related to the ability of MP to bind water. With the increasing degree of protein denaturation, the binding force of bound water decreased, and the P21 reduced from 3.22 to 3.09%, a decrease of 4.04%.

Table 1.

Effects of temperature on spin–spin relaxation times T2 and populations of BFS after 12 h storage

| Time (h) | 0 °C | 10 °C | 20 °C | 30 °C | 40 °C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T21 (ms) | Control | 4.21 ± 0.19 | ||||

| 2 | 3.71 ± 0.13Aa | 4.17 ± 0.33Ab | 3.47 ± 0.22Aa | 3.39 ± 0.16Aa | 4.45 ± 0.27Ab | |

| 4 | 3.94 ± 0.45Aab | 4.28 ± 0.26Ab | 3.72 ± 0.17Aa | 4.3 ± 0.19Ab | 4.21 ± 0.29Ab | |

| 6 | 3.77 ± 0.38Aab | 4.26 ± 0.11Ac | 3.81 ± 0.42Aab | 3.28 ± 0.24Aa | 4.03 ± 0.33Ab | |

| 8 | 4.21 ± 0.29Ab | 4.07 ± 0.32Aa | 4.25 ± 0.31Ab | 3.9 ± 0.22Aa | 4.35 ± 0.12Ab | |

| 10 | 4.05 ± 0.42Ab | 4.31 ± 0.14Ac | 3.54 ± 0.18Aa | 3.93 ± 0.35Ab | 4.48 ± 0.30Ac | |

| 12 | 4.14 ± 0.37Aa | 4.11 ± 0.39Aa | 4.39 ± 0.12Ab | 4.29 ± 0.17Ab | 4.74 ± 0.18Ab | |

| P21 area percentage (%) | Control | 3.22 ± 0.00 | ||||

| 2 | 3.11 ± 0.00Aa | 3.23 ± 0.00Ba | 3.03 ± 0.00Aa | 3.09 ± 0.00Aa | 3.12 ± 0.00Aa | |

| 4 | 3.03 ± 0.00Aa | 3.05 ± 0.01Aa | 3.02 ± 0.00Aa | 3.1 ± 0.00Aa | 2.97 ± 0.00Aa | |

| 6 | 2.96 ± 0.00Aa | 2.92 ± 0.01Aa | 2.95 ± 0.00Aa | 2.93 ± 0.00Aa | 3.01 ± 0.00Aa | |

| 8 | 3.00 ± 0.00Aa | 2.97 ± 0.00Aa | 3.05 ± 0.00Aa | 3.06 ± 0.00Aa | 3.11 ± 0.00Aa | |

| 10 | 3.15 ± 0.00Aab | 3.26 ± 0.00Bb | 3.15 ± 0.00ABab | 3.08 ± 0.00Aa | 3.09 ± 0.00Aa | |

| 12 | 3.09 ± 0.00Aa | 3.10 ± 0.00ABa | 3.29 ± 0.01Bb | 3.29 ± 0.00Bb | 3.03 ± 0.01Aa | |

| Control | 86.45 ± 5.75 | |||||

| T22 (ms) | 2 | 80.71 ± 4.42Aa | 88.39 ± 4.91Ab | 88.91 ± 3.56bA | 89.14 ± 6.18Ab | 98.91 ± 7.43BCc |

| 4 | 79.75 ± 3.79Aa | 94.34 ± 3.57Bc | 88.91 ± 3.90Ab | 88.39 ± 4.93Ab | 89.11 ± 5.27Ab | |

| 6 | 79.11 ± 7.43Aa | 95.28 ± 5.24Bc | 88.91 ± 5.29Ab | 88.39 ± 7.28Ab | 91.27 ± 9.04Abc | |

| 8 | 82.67 ± 3.79Aa | 97.33 ± 6.62Bc | 93.52 ± 9.94ABb | 93.01 ± 5.57ABb | 96.7 ± 8.73Bc | |

| 10 | 81.77 ± 4.95Aa | 102.05 ± 7.03Cc | 91.37 ± 8.86ABb | 104.34 ± 3.61ABc | 99.05 ± 9.22BCc | |

| 12 | 82.61 ± 5.25Aa | 99.67 ± 6.11BCb | 95.77 ± 4.38Bb | 102.73 ± 4.89ABc | 101.83 ± 3.76Cc | |

| P22 area percentage (%) | Control | 89.18 ± 0.00 | ||||

| 2 | 91.84 ± 0.00Cd | 90.77 ± 0.00Cc | 89.76 ± 0.00Cb | 89.93 ± 0.00BCb | 88.59 ± 0.00Ba | |

| 4 | 91.12 ± 0.00Bb | 90.03 ± 0.00Bab | 89.71 ± 0.00Ca | 90.46 ± 0.00Cb | 89.64 ± 0.01Ca | |

| 6 | 91.07 ± 0.00Cc | 89.43 ± 0.00ABa | 89.48 ± 0.00Ba | 89.23 ± 0.01Ba | 89.87 ± 0.00Cb | |

| 8 | 90.02 ± 0.01Bc | 90.49 ± 0.00Cc | 88.09 ± 0.00Aa | 88.17 ± 0.00Ba | 88.64 ± 0.00Bb | |

| 10 | 89.61 ± 0.00ABb | 89.04 ± 0.00ABb | 89.13 ± 0.00Bb | 87.88 ± 0.00Aa | 87.29 ± 0.00Aa | |

| 12 | 88.45 ± 0.00Aab | 88.72 ± 0.01Ab | 88.09 ± 0.00Ab | 87.41 ± 0.00Aa | 87.17 ± 0.00Aa | |

| T23 (ms) | Control | 149.33 ± 2.74 | ||||

| 2 | 108.57 ± 3.22Ab | 138.1 ± 9.76Cc | 132.1 ± 7.85Cc | 78.09 ± 4.46Aa | 134.12 ± 3.75ABc | |

| 4 | 138.09 ± 9.32Bc | 138.09 ± 7.04Cc | 120.57 ± 5.38ABab | 108.57 ± 8.64BCa | 129.75 ± 3.87Ab | |

| 6 | 102.81 ± 3.24Aa | 119.86 ± 4.09ABb | 129.1 ± 6.07Bbc | 120.11 ± 5.37Cb | 130.91 ± 5.11Ac | |

| 8 | 132.1 ± 4.03Bc | 111.8 ± 3.88Ab | 91.83 ± 2.03Aa | 94.43 ± 9.94Ba | 135.61 ± 3.27ABc | |

| 10 | 103.04 ± 7.71Aa | 126.1 ± 2.54Bc | 114.57 ± 7.90ABb | 133.02 ± 6.17CDc | 140.77 ± 0.00Bd | |

| 12 | 109.35 ± 5.29Aa | 108.77 ± 8.33Aa | 120.97 ± 4.38ABb | 147.13 ± 8.62Dc | 153.12 ± 4.98Cc | |

| P23 area percentage (%) | Control | 6.61 ± 0.00 | ||||

| 2 | 5.05 ± 0.01Aa | 6.00 ± 0.00Aab | 7.21 ± 0.00Ac | 6.98 ± 0.00Aab | 8.29 ± 0.00Bb | |

| 4 | 5.85 ± 0.00ABa | 6.92 ± 0.00Aab | 7.27 ± 0.00Ab | 6.44 ± 0.00Aa | 7.39 ± 0.00Aa | |

| 6 | 5.97 ± 0.00Aa | 7.65 ± 0.00Bb | 7.57 ± 0.00Ab | 7.84 ± 0.00Bab | 7.12 ± 0.00Aab | |

| 8 | 6.98 ± 0.00ABa | 6.54 ± 0.00Ab | 8.86 ± 0.00Bb | 8.77 ± 0.00CCa | 8.25 ± 0.00Bab | |

| 10 | 7.24 ± 0.00Ba | 7.70 ± 0.00Bab | 7.72 ± 0.00Aab | 9.04 ± 0.00Cb | 9.62 ± 0.00Cc | |

| 12 | 8.46 ± 0.00Ca | 8.18 ± 0.00Ba | 8.62 ± 0.00Bb | 9.30 ± 0.00Cc | 9.8 ± 0.00Cc | |

aDifferent lower case letters within same row data indicate significant indicate significant differences at 0.05 level, values are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 5)

bControl: freshly fried finished BFS of 0 h

As seen in Table 1, there was a negative correlation between P22 and moisture loss. The results indicated that immobilized water could easily be affected by muscle tissue structure and functional properties, which was consistent with the finding of Chen et al. (2015). With the increase of temperature, T21 increased gradually, from 4.21 ms in 0 h to 4.74 ms in 12 h, the binding force of protein to water became weaken, the degree of freedom of bound water increased significantly. Temperature had a significant effect on the relaxation time of combined water (p < 0.05). Immobilized water peak delay (T22) significantly affected by temperature, T22 rose significantly from 86.45% in 0 h to 101.83% in 12 h, an increase of 17.79% (p < 0.05). The peak delay of immobilized water was gradually prolonged, and the degree of freedom of water increased gradually, which indicated that the immobilized water was significantly affected by protein oxidation. The most obvious change occurs in the mass transfer of water, and the combination with protein becomes loose. The relative moisture content (P23) of meat slices stored at 30 and 40 °C increased significantly, and the temperature affected significantly, P23 significantly from 6.61% in 0 h to 9.8% in 12 h, an increase of 48.26% (p < 0.05). The results showed that the immobilized water, as the oxidation intensifies, was converted to free water. The immobilized water loss may accelerate the oxidation of protein in the meat.

Analysis of secondary structure of MP by FTIR

The secondary structure of a protein refers to the way in which protein molecules are coiled and folded in a certain direction on the basis of the primary structure (Bolotina et al., 1980), and the secondary structure forms a local spatial conformation under the action of hydrogen bonds in the molecule. It mainly includes α-helix, β-sheet, corner, and random curl. FTIR could reveal the amino groups in protein molecule, amide I band (H–O–H bending vibration and C–O stretching vibration), amide II band (N–H bending), amide III band (C–O, C–O–C vibration), C–C vibration and C–O–O glycosidic bond vibrational bands in protein ring structures (Barth, 2007). The main secondary structure bands are shown in Table 2 (Lodha and Netraval, 2005; Monsoor, 2005; Schmidt et al., 2005).

Table 2.

Amide I frequency and assignment of protein

| Frequency (cm) | Assignment | Frequency (cm) | Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1615–1637 | β-sheet | 1637–1645 | No rules curl |

| 1682–1700 | β-sheet | 1664–1681 | β-turn |

| 1646–1664 | Alpha-helix |

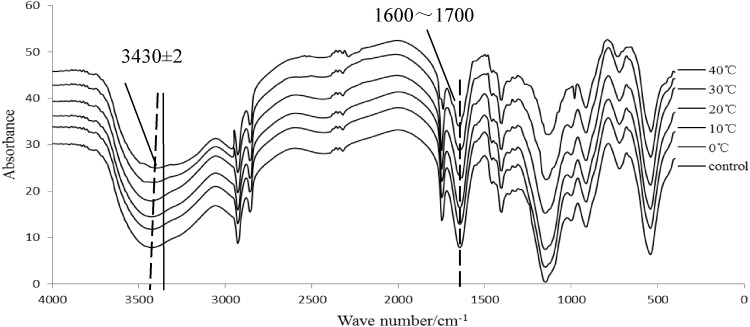

The infrared spectrum of BFS during short-term storage is shown in Fig. 1, The 3430 cm−1 absorption peak position migration occurred, from 0 to 40 °C absorption peak migration − 2 cm−1. It shows that the temperature increases, the O–H group in the protein molecule has a weakening of stretching vibration. The band of 1600–1700 cm−1 is amide I band. It can be seen from the Fig. 1 that the absorption peak stretching vibration was weakened at this time. Quantitative and qualitative analysis deserve further investigation for the main secondary structure.

Fig. 1.

FTIR spectra of myofibrillar during short-time storage

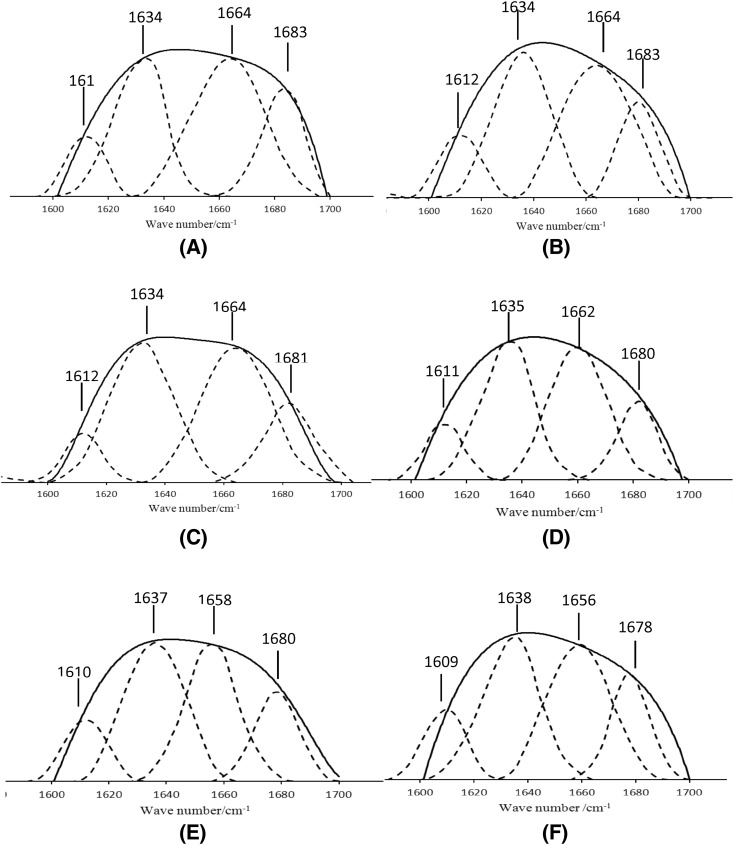

The peak shapes of the amide I and amide II bands were unaffected by the protein side chain structure in FTIR analysis. They were affected by the secondary structure of the protein backbone (Carbonaro et al., 2000). Deconvolution, second-order derivative fitting method was applied to determine the secondary structure changes. The quantitative results of the major secondary structures are shown in Table 3. As shown in Fig. 2, there is no significant change in each band at 0–10 °C. The results indicated that protein oxidation degree was lower at lower temperature, while the secondary structure of MP changed significantly when the temperature increased to 20 °C. Compared to the fresh frying group, the peak of 1612 cm−1 migrated with the increase of temperature during storage. The peak of 1612 cm−1 migrated − 2 cm−1 when stored at 30 °C for 12 h and − 3 cm−1 when stored at 40 °C for 12 h. The results show that MP molecules between the side chains increased vibration, protein molecular polymerization, and the occurrence of intermolecular connections (Jackson and Mantsch, 1992). The results are consistent with the previous electrophoresis studies. Under high temperature conditions, myosin peptide chain disulfide-based displayed polymerization, the tertiary structure changed to form a macromolecular polymer, and the side chain vibration increased. The peak located at 1634 cm−1 20 °C migration + 1 cm−1, 40 °C migration + 4 cm−1, indicating that the MP are unfolded, the β-sheet is reduced to a random coil. From the quantitative changes in Table 3, the number of β-sheet at 40 °C decreased by 16.54%, the trend is irregular structure. When the temperature was 20 °C, the peak at 1664 cm−1 migrated to − 6 cm−1 and the peak at 1664 cm−1 migrated − 8 cm−1 at 40 °C showed that the hydrogen bond stretching vibration of the peptide chain was weakened, α-helix to random coil structure transition. At 40 °C, the content of α-helix decreased by 22.90% compared with the complete frying. At the same time the peak of 1683 cm−1 migrated − 5 cm−1. The temperature changes may lead to the β-sheet structure changed, which tends to be β-turn structure. The number of β-turn increased by 15.88% and more ordered structure transformed into β-turn. The number of irregular curls increased from the initial 8.14 to 15.72%, an increase of 93.12%, indicating that the main structure of the temperature increasing protein α-helix, β-sheet changes, increased protein denaturation, protein ordered structure to the disorderly structure. During storage, the secondary structure of the protein changes most α-helix. Results indicated that α-helix plays an important role in maintaining the secondary structure of MP.

Table 3.

Changes of secondary structure of MP during short-term storage

| % | Control | Temperature (°C) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | ||

| Alpha-helix | 31.96 ± 0.87a | 31.74 ± 0.64a | 31.14 ± 1.15a | 29.33 ± 1.22ab | 27.37 ± 0.96b | 24.64 ± 0.88c |

| β-sheet | 36.81 ± 1.04a | 35.87 ± 1.12a | 35.68 ± 0.93a | 34.31 ± 0.79ab | 32.28 ± 1.02b | 30.72 ± 0.75c |

| No rules curl | 8.14 ± 0.76a | 8.63 ± 0.53a | 9.22 ± 0.57ab | 12.54 ± 0.68b | 15.24 ± 0.49c | 15.72 ± 1.06d |

| β-turn | 23.23 ± 0.77a | 23.78 ± 0.39a | 23.96 ± 0.84a | 23.82 ± 0.81a | 25.11 ± 1.13b | 26.92 ± 0.93c |

aValues with different superscripts within the same line are significantly different (p < 0.05), as determined by the Duncan’s test

bValues are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 5)

Fig. 2.

Amide I band curve fitting map. (A) Control, (B) 0 °C, (C) 10 °C, (D) 20 °C, (E) 30 °C, (F) 40 °C

Correlation analysis between LF-NMR and FTIR

The results of LF-NMR experiment show that when the temperature is higher than 30 °C, the oxidation of protein aggravates and the particle size decreases. At this time, T22 prolongs and P22 decreases. Combined with the FTIR results that during the storage process, with the increase of temperature, the T21 delay gradually lengthens and the P21 decreases, with the increase of the degree of freedom of binding water, the binding of protein becomes loose. At this time, intramolecular and intermolecular hydrogen bonds formed by the binding of the O–H group in the water with the C=O in the amino acid become weak in the infrared spectrum, and the structure of the MP changes. This shows that the immobilized water loss significantly, The binding between MP and water becomes loose. Therefore, it can be inferred that MP affect the degree of binding to water because of secondary structure changes during short-term storage. It is speculated that MP α-helix, β-sheet structure is more conducive to protein binding to water than β-turn and irregular curly structure.

Using Pearson Correlation Coefficient Method to Analyze the Correlation between LF-NMR and FTIR. When R > 0, the two variables are positively correlated, and when R < 0, the two variables are negatively correlated. When |R| = 1, it means that the two variables are completely linearly related, they are functional relationships. When R = 0, the radio correlation between the two variables is represented. In the correlation analysis, the significance is generally divided into three levels: |R| < 0.4 is a low linear correlation; 0.4 ≤ |R| < 0.7 is a significant correlation; 0.7 ≤ |R| < 1 is a highly linear correlation. The correlation coefficient method was used to analyze the correlation between T2 and FTIR, and the results are shown in the following Table 4. As can be seen from the table, there is a high correlation between T2 and the secondary structure of MP. Such as T2 was negatively correlated with α-helix and β-sheet; while between T2 and α-helix and β-turn has a positive correlation. Further analysis suggests that T21 may have a significant effect on α-helix, β-sheet, irregular curl and β-turn. There was a significant correlation between T22, T23 and secondary structure. As can be seen from the characteristic peak area, there is no obvious correlation between P21 and secondary structure, and the effect of bound water loss on secondary structure is insignificant. There was a high correlation between P22 and P23 and secondary structures. P22 had a very high positive correlation with α-helix and β-sheet, but a relatively high negative correlation with irregular curl and β-turn. In contrast to P22, P23 has a very high negative correlation with α-helix and β-sheet, and a relatively high positive correlation with random coil and β-turn. The results show that the more content of flow water is, the more α-helix, β-sheet structure content is, while the less content of random structure. Free water content is higher, the less α-helix, β-sheet structure. Therefore, it is further verified that the decrease of P22 and the loss of easily flowing water are the main causes of random coil curl and β-turn increase, which is immobilized water plays an important role in maintaining the secondary structure of MP. These are consistent with the previous experimental results.

Table 4.

T2 and FTIR correlation analysis

| α-Helix | β-sheet | No rules curl | β-turn | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T21 (ms) | − 0.89* | − 0.84* | 0.79* | 0.85* |

| P21 area (%) | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.11 | − 0.42 |

| T22 (ms) | − 0.75* | − 0.75* | 0.79* | 0.67 |

| P22 area (%) | 0.94* | 0.98* | − 0.96* | − 0.88* |

| T23 (ms) | − 0.60 | − 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.53 |

| P23 area (%) | − 0.84* | − 0.89* | 0.85* | 0.83* |

The “*” in the table indicates R > 0.7, significant p < 0.01

Acknowledgements

Heilongjiang Bayi Agricultural University Dr. research fund.

References

- Aursand IG. Low-field NMR and MRI studies of fish muscle: effects of raw material quality and processing. Doctoral Theses at Ntnu (2009)

- Barth A. Infrared spectroscopy of proteins. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta. 2007;1767:1073–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthomieu C, Hienerwadel R. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. Photosynth Res. 2009;101:157. doi: 10.1007/s11120-009-9439-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolotina IA, Chekhov VO, Viu L, Finkel’Shteĭn AV, Ptitsyn OB. Determination of the secondary structure of proteins from their circular dichroism spectra. I. Protein reference spectra for alpha-, beta- and irregular structures. Molekuliarnaia Biologiia. 1980;14:891–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonaro M, Grant G, Cappelloni M, Pusztai A. Perspectives into factors limiting in vivo digestion of legume proteins: antinutritional compounds or storage proteins? J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000;48:742–749. doi: 10.1021/jf991005m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Zhou GH, Zhang WG. Effects of high oxygen packaging on tenderness and water holding capacity of pork through protein oxidation. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2015;8:2287–2297. doi: 10.1007/s11947-015-1566-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerasimowicz WV, Byler DM, Susi H. Resolution-enhanced FT-IR spectra of soil constituents: humic acid. Appl. Spectrosc. 1986;40:504–506. doi: 10.1366/0003702864508953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Wang R, Yang M. Moisture dynamic change studies of battered and fried pork slices during short-term storage. Food Sci. 2016;37:268–273. [Google Scholar]

- Hullberg A, Bertram HC. Relationships between sensory perception and water distribution determined by low-field NMR T2 relaxation in processed pork—impact of tumbling and RN–allele. Meat Sci. 2005;69:709–720. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro T, Ono T, Wada T, Tsukamoto C, Kono Y. Changes in soybean phytate content as a result of field growing conditions and influence on tofu texture. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2006;70:874–880. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M, Mantsch HH. Bio-analytical applications of fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 1992;11:206–210. doi: 10.1016/0165-9936(92)80044-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jung C. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy as a tool to study structural properties of cytochromes P450 (CYPs) Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008;392:1031–1058. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-2216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong B, Guo Y, Xia X, Liu Q, Li Y, Chen HS. Cryoprotectants reduce protein oxidation and structure deterioration induced by freeze-thaw cycles in common carp (Cyprinus carpio) surimi. Food Biophysics. 2013;8:104–111. doi: 10.1007/s11483-012-9281-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Liu D, Zhou G, Xu X, Qi J, Shi P, Xia T. Meat quality and cooking attributes of thawed pork with different low field NMR T21. Meat Sci. 2012;92:79. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodha P, Netravali AN. Thermal and mechanical properties of environment-friendly ‘green’ plastics from stearic acid modified-soy protein isolate. Ind. Crops Sprod. 2005;21:49–64. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2003.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meersman F, Smeller L, Heremans K. Comparative fourier transform infrared spectroscopy study of cold-, pressure-, and heat-induced unfolding and aggregation of myoglobin. Biophys. J. 2002;82:2635. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75605-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklos R, Mora-Gallego H, Larsen FH, Serra X, Cheong LZ, Xu X, Arnau J, Lametsch R. Influence of lipid type on water and fat mobility in fermented sausages studied by low-field NMR. Meat Sci. 2014;96:617–622. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2013.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsoor MA. Effect of drying methods on the functional properties of soy hull pectin. Carbohydr. Polym. 2005;61:362–367. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2005.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park D, Xiong YL, Alderton AL. Concentration effects of hydroxyl radical oxidizing systems on biochemical properties of porcine muscle myofibrillar protein. Food Chem. 2007;101:1239–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.03.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Promeyrat A, Gatellier P, Lebret B, Kajak-Siemaszko K, Aubry L, Santé-Lhoutellier V. Evaluation of protein aggregation in cooked meat. Food Chem. 2010;121:412–417. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.12.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Renou JP, Foucat L, Bonny JM. Magnetic resonance imaging studies of water interactions in meat. Food Chem. 2003;82:35–39. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(02)00582-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt V, Giacomelli C, Soldi V. Thermal stability of films formed by soy protein isolate–sodium dodecyl sulfate. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2005;87:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2004.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sørland GH, Larsen PM, Lundby F, Rudi AP, Guiheneuf T. Determination of total fat and moisture content in meat using low field NMR. Meat Scince. 2004;66:543. doi: 10.1016/S0309-1740(03)00157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Bertram HC, Kohler A, Böcker U, Ofstad R, Andersen HJ. Influence of aging and salting on protein secondary structures and water distribution in uncooked and cooked pork. A combined FT-IR microspectroscopy and 1H NMR relaxometry study. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:8589–8597. doi: 10.1021/jf061576w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zając A, Dymińska L, Lorenc J, Hanuza J. Fourier transform infrared and raman spectroscopy studies of the time-dependent changes in chicken meat as a tool for recording spoilage processes. Food Anal. Methods. 2017;10:640–648. doi: 10.1007/s12161-016-0636-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]