Abstract

This study evaluated the applicability of isomaltulose as a sucrose substitute in the osmotic extraction of Prunus mume fruit juice. Isomaltulose (20 mM) significantly reduced the uptake of a fluorescent tracer—2-[N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diaxol-4-yl) amino]-2-deoxyglucose. Juice extracted by isomaltulose had similar pH and titratable acidity values to those of the other sugars. Citric and malic acids were the main organic acids in the extracted juices. The radical-scavenging ability of the plum juice extracted by isomaltulose was significantly higher than in juices extracted by other sugars (p < 0.05) and polyphenols content of the juice was also significantly higher than those of other sugars. The blood glucose level of P. mume juice extracted by fructose or isomaltulose was increased slowly compared to the juice extracted by sucrose. Therefore, the use of isomaltulose or an isomaltulose mixture in the manufacture of P. mume juice will help maintain health by reducing sugar intake.

Keywords: Isomaltulose, Prunus mume, Osmotic extraction, Blood glucose

Introduction

Prunus mume produces a fruit, commonly known as Maesil in Korea, which is popular in Eastern Asia owing to its flavor and aroma, as well as its nutritional and therapeutic qualities. Prunus mume Sieb. et Zucc., a member of the Rosaceae family, is the most popular fruit tree in Korea, China, and Japan (Choi and Koh, 2017). The fruit is used to make plum pickle, sauce, juice, and liquor in these countries. Prunus mume and its products are widely consumed because of their health benefits, and are considered as natural remedies for many diseases (Sacilik et al., 2006).

Osmotic extraction using sugar is a traditional method that has been used to process plum products for many years. This method relies on the principle that soluble components can be liberated from fruit by osmotic pressure generated by the addition of sucrose (Ko and Yang, 2009). Osmotic extraction has attracted attention as a pre-drying or extraction process that can saves energy and improves food quality (Sereno et al., 2001).

The consumption of juice extracted from P. mume fruit is steadily increasing as consumers seek its health benefits. However, sucrose, which is used for the osmotic extraction, is recognized as a highly carcinogenic and diabetes-inducing sugar (Mardis, 2001; Xiao et al., 2018). To solve these problems, substitute sweeteners should be used instead of sucrose. Isomaltulose (6-O-α-d-glucopyranosyl-d-fructose) is a noncarcinogenic sweetener with a low glycemic index that could fulfil customers’ requirements (Marta et al., 2008). Isomaltulose has a similar taste and appearance to sucrose, but is approximately half as sweet. Absorption and release of monosaccharides by isomaltulose after ingestion proceed slowly. Blood glucose and insulin levels are elevated more slowly and maximum blood glucose level is also reached gradually (Lina et al., 2002).

It is important to understand the changes in the components of P. mume juice that has been osmotically extracted using isomaltulose instead of sucrose, because this may affect the quality of the product. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to evaluate the applicability of isomaltulose as a substitute for sucrose in the osmotic extraction of juice from P. mume fruits. We were particularly interested in the effects of isomaltulose on the efficiency of osmotic extraction and the quality of the product. We also assessed the health benefits of juice prepared by extraction using isomaltulose by measuring blood glucose changes following ingestion of the juice.

Materials and methods

Materials

We purchased P. mume fruits from retail stores in Seoul, South Korea. Fruit itself of uniform mass (10–12 ± 1.0 g) were subjected to osmotic extraction. The sugars for osmotic extraction (sucrose, isomaltulose, and fructose,) were obtained from Neo Cremar Co. Ltd. (Seoul, Korea). Folin–Ciocalteu phenol reagent, 2,2-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl hydrate (DPPH), 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS), and 2-[N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diaxol-4-yl) amino]-2-deoxyglucose (2-NBDG) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Other chemicals used in the analysis were high-purity grade.

Osmotic extraction

The fruits were washed with tap water and drained. Five portions of fruit (500 g each) were respectively placed in five 2-L glass bottles and mixed with 500 g of sucrose, fructose, isomaltulose, a mixture of fructose and isomaltulose (1:1, 250 g each), or a mixture of sucrose and isomaltulose (1:1, 250 g each). The mixtures of fruit and sugar were stored for up to 90 days at 15 °C. We used a mixing ratio of sugar to fruit that is widely used in juice production by osmotic extraction (Ko and Yang, 2009). After osmotic extraction, the extracts were filtered through cloth, and the filtrate was used for the experiments.

Analytical methods

The browning index of the juice was calculated by measuring the absorbance at 420 nm using a spectrophotometer (Spectronic Instruments, Rochester, NY, USA). The soluble solid content of the juice was measured using a 60/70 refractometer (Bellingham and Stanley Ltd., Tunbridge Wells, UK) and expressed as Brix. The pH of the juice was determined using an Orion 3-Star pH meter (Thermo Scientific, Beverly, MA, USA). The juice was titrated with 0.1 M NaOH to pH 8.3 to measure the titratable acidity, which was calculated as a percentage of citric acid. The total polyphenols content was determined by the Folin–Ciocalteu method (Singleton et al., 1999) on a microscale level using gallic acid as the standard.

Measurement of organic acids content

The organic acids content was measured through a slightly modified version of the method described by Jayabalan et al. (2007). The diluted juices were supplied to a Sep-Pak C18 cartridge (Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA) and filtered through a 0.45-μm membrane syringe filter (Millipore, USA, Bedford, MA, USA). A 10-μL sample of each filtrate was injected into an Agilent 1100 high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a diode array detector. An YMC Triart C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm; YMC Co. Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) was used at 28 °C; the mobile phase comprised a mixture of 20 mM potassium dihydrogen phosphate (pH 2.4) and methanol (97:3), and the flow rate was 1.0 mL/min. Detection was carried out at 220 nm, and the organic acids were quantified from standard curves.

2-NBDG uptake measurements

Male Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats (Central Lab. Animal Inc., Seoul, Korea) weighing 250–300 g were used for all experiments. After fasting for 18 h, the rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg). A 9-cm section of each rat’s jejunum was identified according to the procedure described elsewhere (Ahnen et al., 1986) and collected. Each isolated jejunum was divided into 1.5-cm segments.

Briefly, the tissue fragments were soaked in the test solutions and incubated for 45 min with a standard buffer containing various concentrations of 2-NBDG plus 220 mM mannitol, 25 mM Na2SO4, 2 mM K2HPO4, 1.5 mM CaSO4·2H2O, 1 mM MgSO4·7H2O, and 0.5 mM KH2PO4 at pH 7.4 in the dark at room temperature. After incubation, the specimens were washed thoroughly three times with cold standard buffer to remove any 2-NBDG remaining on the surface. Each specimen was then pulverized with a metal bead cell disruptor. The samples were then centrifuged and the supernatants were extracted. The fluorescence intensity of each supernatant was measured to determine the amount of 2-NBDG, which is a sensitive probe used to monitor glucose uptake in intestinal cells. Each sample had three replicates. The fluorescence intensity of cellular 2-NBDG in each well was measured with a fluorescence microplate reader (Molecular Devices, USA) with fluorescent filters (excitation wavelength: 488 nm; emission wavelength: 542 nm) (Xu et al., 2012).

Radical-scavenging activity and oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)

The ability of each juice sample to scavenge DPPH was determined by the method described by Quang et al. (2003), and the ability of each juice sample to scavenge ABTS was determined by the method described by Wang and Xiong (2005). All tests were performed in triplicate.

Male SD rats (Central Lab. Animal Inc., Seoul, Korea) weighing 130–150 g were used for the OGTTs. Oral glucose tolerance tests were conducted to evaluate the effects of plum juice on the changes of blood glucose. Briefly, after fasting for 15 h, plum juice (2 g per kg of body weight) was administrated to the fasted animals, and blood samples were periodically collected from the tail vein of each rat. Blood glucose levels were measured with a Super Glucocard II glucose analyzer (ARKRAY Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The protocol for the animal tests was approved by the Korea University Animal Care Committee (KUIACUC-2018-7).

Statistical analysis

The data obtained from three repeated experiments are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan’s multiple range test using an SPSS statistical package (SPSS Inc., IL, USA).

Results and discussion

Effect of isomaltulose on glucose and sucrose absorption

Figure 1 shows glucose absorption when 0, 5, 10, and 20 mM isomaltulose was added to 20 mM 2-NBDG. The absorption of 2-NBDG was inversely proportional to the isomaltulose concentration. In particular, the addition of 20 mM isomaltulose caused a significant decrease in 2-NBDG uptake, compared to the absence of isomaltulose (p < 0.05). This result supports the observation that isomaltulose causes a gradual increase in blood glucose without any adverse effects (Kawai et al., 1989). Isomaltulose might also inhibit the increase in blood glucose due to other carbohydrates, such as glucose, sucrose, and dextrin (Kashimura et al., 2008).

Fig. 1.

Effect of isomaltulose on glucose and sucrose absorption. The absorption rate of glucose in the intestinal segments was measured after 40 min of incubation with standard buffer. Error bars represent the standard deviation of triplicate measurements. The letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05)

Kashimura et al. (2003) reported that the consumption of a mixture of isomaltulose and sucrose reduces the increase in blood glucose concentration compared with the digestion of sucrose alone. However, it is unclear whether the inhibition of sucrose digestion in the presence of isomaltulose is due to the inhibition of sucrase activity by isomaltulose. When glucose is produced by sucrase–isomaltulase (EC 3.2.1.10), it interferes with the absorption of 2-NBDG. The level of 2-NBDG uptake was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in the presence of isomaltulose than in its absence. This result indicates that 2-NBDG was absorbed instead of glucose because the degradation of sucrose was inhibited in the presence of isomaltulose. Kashimura and Nagai (2007) also demonstrated the inhibitory effect of isomaltulose on the degradation of sucrose by antagonizing the enzyme that hydrolyzes sucrose in isolated segments of intestine. They also reported that disaccharides with an α-1,6-glucosyl bond competitively inhibit intestinal α-glucosidases and may reduce the rate of hydrolysis of sucrose and other α-glucosyl-linked saccharides.

Changes of the soluble solids content, browning index, pH, and titratable acidity during osmotic extraction

The soluble solids content, browning index, pH, and titratable acidity significantly affect the taste and quality of osmotically extracted fruit juice. The soluble solids content values for the juices extracted from P. mume fruits are shown in Fig. 2. The soluble solids content increased up to 15 days and changed insignificantly thereafter. The soluble solids content values of the fructose- and sucrose-extracted juices were higher than those of the other sugar-extracted juices.

Fig. 2.

Changes in soluble solids content, browning index, pH, and titratable acidity during osmotic extraction with various sweeteners. The osmotically extracted juices were passed through filter paper, and the filtrates were analyzed. Error bars represent the standard deviation of triplicate measurements. The letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05)

pH also increased sharply up to 15 days, and the increase was slight thereafter. The pH of P. mume fruit is between 2.5 and 3.0 (Cha et al., 1999). There was no significant difference in pH among the osmotically extracted juices after 90 days. That is, the pH of all extracted juices was approximately 2.7–3.0. The sugars used for osmotic extraction did not influence the pH of the juice from P. mume fruits. However, the titratable acidity of the juice extracted by fructose was significantly lower than that of the other juices. The titratable acidity values of the juices extracted from P. mume fruits were similar to those reported previously, except when fructose was used for extraction (Ko and Yang, 2009).

The color of the fruit extract or juice is generally recognized as an important quality indicator. The extract or juice from P. mume fruits is often colorless to reddish-brown when the packaged product is stored. The browning index of the juices extracted from P. mume fruit is presented in Fig. 2. The browning index was significantly higher in the juices extracted by isomaltulose than in the other juices. The browning index of sugar-extracted juice tended to be lower when the juice was extracted by reducing sugars (fructose, isomaltulose, or a mixture containing isomaltulose).

Changes in the organic acid composition, polyphenols content, and radical-scavenging activities of the plum juices

Prunus mume fruit contain organic acids and active components with radical-scavenging activity (Quang et al., 2003). The characteristic acidity of P. mume fruits is caused by organic acids including citric and malic acids. The predominant organic acid in P. mume juice is citric acid, followed by small amounts of oxalic and malic acids. Chou (1993) studied the organic acids in P. mume juices of various origins and ages, and reported differences among them. We found that citric and malic acids were the predominant organic acids in the osmotically extracted P. mume fruit juices (Table 1). The juice extracted by fructose had a higher content of malic acid than the other osmotically extracted juices. The citric acid in P. mume fruits has various health benefits (Kubo et al., 2005; Shirasaka et al., 2005).

Table 1.

Comparison of the organic acid content of juice that was osmotically extracted from Prunus mume fruits

| Organic acid | Sucrose | Fructose | Isomaltulose | Fructose/isomaltulose | Sucrose/isomaltulose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxalic acid | 0.30 ± 0.09ns | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 0.32 ± 0.03 |

| Citric acid | 25.85 ± 6.63a | 16.76 ± 0.75b | 22.95 ± 0.58a | 22.60 ± 0.27a | 22.58 ± 0.10a |

| Malic acid | 22.98 ± 5.22b | 30.59 ± 2.38a | 18.30 ± 1.30b | 20.12 ± 0.93b | 12.30 ± 2.06c |

| Succinic acid | ND | 2.99 ± 0.67c | ND | 4.02 ± 0.01a | 3.85 ± 0.10b |

| Fumaric acid | ND | 0.04 ± 0.01 | ND | 0.05 ± 0.01 | ND |

ND not detected

The superscripted letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05)

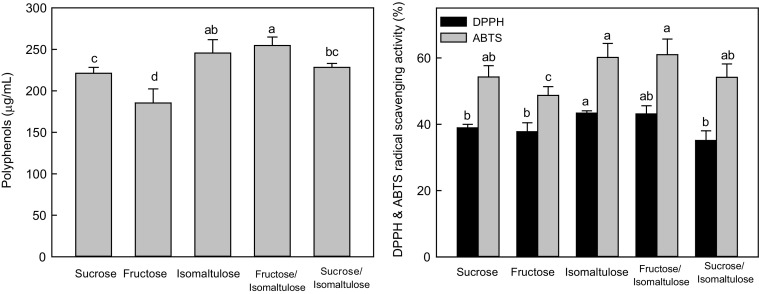

Figure 3 shows the polyphenols content and radical-scavenging activity of the plum juices prepared by osmotic extraction. The polyphenols content was significantly higher in fruit juice extracted by isomaltulose than in juice extracted by sucrose (p < 0.05). Radical-scavenging activity followed a similar pattern to that of polyphenols content. When isomaltulose was used, the radical-scavenging ability of P. mume juice was significantly higher than it of the juices extracted by the other sugars (p < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Changes of polyphenols contents and radical-scavenging activities of plum juices prepared with various sweeteners. Error bars represent the standard deviation of triplicate measurements. The letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05)

In plants, many antioxidant polyphenols exist in a form that is covalently bonded to insoluble polymers (Niwa et al., 1988). If this bonding is weak, osmotic extraction can liberate and activate low-molecular-weight natural antioxidants in plants. Nunez-Mancilla et al. (2013) reported that total antioxidant activity decreased in all the osmotically treated strawberries examined compared with fresh samples. Because antioxidants are liberated at the time of osmotic extraction, the radical-scavenging ability of the juice tends to increase. The use of isomaltulose in the production of plum juice will be beneficial to health because it increases the radical-scavenging ability compared with other sugars (Matsuda el al., 2003).

Changes in blood glucose levels and area under the curve (AUC) values following oral administration of plum juice

Plum juice contains a large amount of sugar, so it is likely to increase blood sugar levels. To solve this problem, alternative sweeteners are used in the preparation of plum juice. Figure 4 shows the changes in blood glucose levels following the consumption of plum juice prepared by osmotic extraction with the various sugars. For some of the juices, the highest glucose levels were observed at 30 min after ingestion. However, when plum juice extracted by fructose/isomaltulose or sucrose/isomaltulose was consumed, the highest blood sugar levels were observed at 1 h after ingestion. The blood glucose levels tended to increase somewhat later when plum juice made with fructose or isomaltulose was ingested.

Fig. 4.

Changes in blood glucose levels and area under the curve (AUC) values following oral administration of plum juice. After fasting for 15 h, plum juice (2 g per kg of body weight) was administrated to Sprague–Dawley rats, and the blood glucose levels were determined. Error bars represent the standard error of triplicate measurements. The letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05)

The highest glucose level was obtained at 30 min after ingesting the juice of plum prepared with sugar. However, in the case of ingestion of plum juice made with fructose or isomaltulose, the highest blood sugar level was observed at 1 h after ingestion. The blood glucose level tended to increase somewhat later in the case of ingestion of plum juice made with fructose or isomaltulose. Isomaltulose is a noncariogenic sweetener that is slowly released into the blood. The physicochemical properties of isomaltulose, which is approximately half as sweet as sucrose, make it to be a good substitute for sucrose in most sweet foods (de Oliva-Neto and Menao, 2009; Peinado et al., 2012).

Juice extracted by isomaltulose had similar pH and titratable acidity values to juices extracted by other sugars, but the solid content was low (36.0–43.9 brix) and the browning index (0.42–0.72) tended to increase. Despite these differences in the characteristics of the extracted plum juice, the juice prepared by isomaltulose exhibited higher radical-scavenging ability and caused less change in blood sugar levels than plum juice extracted by other sugars. Therefore, manufacture of plum juice using isomaltulose or an isomaltulose mixture will help promote health by reducing sugar intake.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahnen DJ, Singleton JR, Hoops TC, Kloppel TM. Posttranslational processing of secretory component in the rat jejunum by a brush-border metalloprotease. J. Clin. Invest. 1986;77:1841–1848. doi: 10.1172/JCI112510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha H, Hwang J, Park J, Park Y, Jo J. Changes in chemical composition of Mume (Prunus mume Sieb. et Zucc) fruits during maturation. Korean J. Postharvest Sci. Technol. 1999;6:481–487. [Google Scholar]

- Choi B, Koh E. Changes in the antioxidant capacity and phenolic compounds of maesil extract during one-year fermentation. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2017;26:89–95. doi: 10.1007/s10068-017-0012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou C. Investigation of the fruit characteristics of Japanese apricot or mei (Prunus mume Seib. et Zucc.) in Taiwan. Mem. Coll. Agric. Natl. Taiwan Univ. 1993;33:31–44. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliva-Neto P, Menao PTP. Isomaltulose production from Sucrose by Protaminobacter rubrum immobilized in calcium alginate. Bioresour. Technol. 2009;100:4252–4256. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayabalan R, Marimuthu S, Swaminathan K. Changes in content of organic acids and tea polyphenols during kombucha tea fermentation. Food Chem. 2007;102:392–398. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.05.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kashimura J, Nagai Y. Inhibitory effect of palatinose on glucose absorption in everted rat gut. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. (Tokyo) 2007;53:87–89. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.53.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashimura J, Nagai Y, Goda T. Inhibitory action of palatinose and its hydrogenated derivatives on the hydrolysis of alpha-glucosylsaccharides in the small intestine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008;56:5892–5895. doi: 10.1021/jf7035824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashimura J, Nagai Y, Shimizu T, Ebashi T. New findings of palatinose function. Proc. Res. Soc. Jpn. Sugar Refin. Technol. 2003;51:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kawai K, Yoshikawa H, Murayama Y, Okuda Y, Yamashita K. Usefulness of palatinose as a caloric sweetener for diabetic-patients. Horm. Metab. Res. 1989;21:338–340. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1009230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko M-S, Yang J-B. Antimicrobial activities of extracts of Prunus mume by sugar. Korean J. Food Preserv. 2009;16:759–764. [Google Scholar]

- Kubo M, Yamazaki M, Matsuda H, Gato N, Kotani T. Effect of fruit-juice concentrate of Japanese apricot (Prunus mume SEIB. et ZUCC) on improving blood fluidity. Nat. Med. 2005;59:22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lina B, Jonker D, Kozianowski G. Isomaltulose (Palatinose®): a review of biological and toxicological studies. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2002;40:1375–1381. doi: 10.1016/S0278-6915(02)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardis AL. Current knowledge of the health effects of sugar intake. Fam. Econ. Nutr. Rev. 2001;13:87–91. [Google Scholar]

- Marta N, Funes LL, Saura D, Micol V. An update on alternative sweeteners. Int. Sugar J. 2008;110:425–429. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda H, Morikawa T, Ishiwada T, Managi H, Kagawa M, Higashi Y, Yoshikawa M. Medicinal flowers. VIII. Radical scavenging constituents from the flowers of Prunus mume: Structure of prunose III. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 2003;51:440–443. doi: 10.1248/cpb.51.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa Y, Kanoh T, Kasama T, Negishi M. Activation of antioxidant activity in natural medicinal products by heating, brewing and lipophilization—a new drug delivery system. Drugs Exp. Clin. Res. 1988;14:361–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez-Mancilla Y, Perez-Won M, Uribe E, Vega-Galvez A, Di Scala K. Osmotic dehydration under high hydrostatic pressure: Effects on antioxidant activity, total phenolics compounds, vitamin C and colour of strawberry (Fragaria vesca) LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2013;52:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2012.02.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peinado I, Rosa E, Heredia A, Andres A. Rheological characteristics of healthy sugar substituted spreadable strawberry product. J. Food Eng. 2012;113:365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2012.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quang DN, Hashimoto T, Nukada M, Yamamoto I, Tanaka M, Asakawa Y. Antioxidant activity of curtisians I-L from the inedible mushroom Paxillus curtisii. Planta Med. 2003;69:1063–1066. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-45159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacilik K, Elicin AK, Unal G. Drying kinetics of Uryani plum in a convective hot-air dryer. J. Food Eng. 2006;76:362–368. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2005.05.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sereno A, Moreira R, Martinez E. Mass transfer coefficients during osmotic dehydration of apple in single and combined aqueous solutions of sugar and salt. J. Food Eng. 2001;47:43–49. doi: 10.1016/S0260-8774(00)00098-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasaka N, Takasaki R, Yoshizumi H. Changes in lyoniresinol content and antioxidative activity of pickled Ume during the seasoning process. J. Jpn. Soc. Food Sci. 2005;52:495–498. doi: 10.3136/nskkk.52.495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton VL, Orthofer R, Lamuela-Raventos RM. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. Oxid. Antioxid. Pt A. 1999;299:152–178. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(99)99017-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LL, Xiong YL. Inhibition of lipid oxidation in cooked beef patties by hydrolyzed potato protein is related to its reducing and radical scavenging ability. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005;53:9186–9192. doi: 10.1021/jf051213g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J, Huang X, Alkhers N, Alzamil H, Alzoubi S, Wu TT, Castillo DA, Campbell F, Davis J, Herzog K. Candida albicans and early childhood caries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Caries Res. 2018;52:102–112. doi: 10.1159/000481833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu TY, Guo LL, Wang P, Song J, Le YY, Viollet B, Miao CY. Chronic exposure to nicotine enhances insulin sensitivity through alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-STAT3 Pathway. PLoS One. 2012;7:1–12. doi: 10.1371/annotation/82b96c01-6435-4856-80a6-0176b1986e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]