Abstract

A total of twenty-one soybean varieties were screened for their morphological characteristics followed by isoflavone content analysis by HPLC. The total isoflavone (TI) content was found within a wide range of 140.9–1048.6 μg/g of soy in different varieties. The highest isoflavone content was found in MAUS-2 followed by DS_2613 and lowest in Karunae (140.9 μg/g of soy). Various isoflavone forms were identified by LC–ESI+ MS. Significant differences in the isoflavone content were observed for all the aglycones and their glucoside conjugates as well as total daidzein, total genistein, total glycitein, and TI. A positive correlation between TI content and growth stages was found during the progression of seed development. An increase of 5.4-fold and 5.3-fold of TI concentration was observed for JS 335 and MAUS-2 respectively, from early to green mature (R5–R8) stage of bean development.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13197-018-3443-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Soybean cultivars, Isoflavones, Malonylglucosides, High performance liquid chromatography, Electrospray ion mass spectrophotometer

Introduction

Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) is an essential legume crop due to its high-quality protein, oil content, and also a rich source of various phytochemicals and folic acid (Barnes 2010). Considering its functionally rich bioactive health-promoting dietary components, soybean and its products gain significant interest by the global consumers (Wardhani et al. 2008; Panat et al. 2016). India stands fifth in soybean production in the world and sixth in terms of leading soybean consuming countries. Out of the total production, 10–12% is directly consumed and the rest is used for processing. Though India contributes to global soybean production, reports pertaining to soybean varieties with potential bioactives specifically isoflavones remain scarce. Isoflavonoids well known as phytoestrogens are a subclass of flavonoids of plant origin and their role in legume-rhizobial and legume-pathogen interactions is reported (Dixon 2004). Isoflavones are abundant in soybeans and soy-based products (Franke et al. 1994; Kuligowski et al. 2017). In soybean, the isoflavones (daidzein, genistein, and glycitein) are synthesized via the phenylpropanoid pathway and stored in the vacuole as glucosyl- and malonyl-glucose conjugates (Graham 1991). The isoflavones genistein and daidzein play a preventing role in breast cancer (He et al. 2015; Kaur and Badhan 2015), in alleviating the osteoporosis, menopausal symptoms, and cardiovascular disease (Cornwell et al. 2004; Isanga and Zhang 2008; Gil-Izquierdo et al. 2012). According to FDA, 25 g of soy protein per day included in the diet is capable of reducing blood cholesterol levels (FDA 1999). Several factors such as the genetic, the environmental, geographical location, storage and variety as well influence the isoflavone content in soybean seeds (Lee et al. 2003; Hasanah et al. 2010; Teekachunhatean et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2014). So there is a need to screen soybean varieties comprising a high bioactive profile of beans. Soybean varieties that have a high quantity of isoflavones are essential as they possess nutraceutical value and commercial significance. It is noted that, during post-harvest processing of soybeans and in manufacturing of various soy-based food products, some inevitable loss in isoflavones content occurs. If soybean varieties with higher levels of these bioactive are cultivated, there is a considerable scope to retain higher levels of such bioactives in products even upon processing that is beneficial to consumers health. In soybean isoflavones, such as genistein, daidzein and glycitein, are synthesized by a branch of the phenylpropanoid pathway (Yu and McGonigle 2005). Dietary isoflavones are mainly composed of 12 different chemical forms and classified into four groups. These groups include aglycone (genistein, daidzein and glycitein), β-glucosides (genistin, daidzin, and glycitin), acetylglucosides (6′-acetyl genistin, 6′-acetyl daidzin, and 6′-acetyl glycitin), malonylglucosides (6′-malonylgenistin, 6′-malonyl daidzin, and 6′-malonyylglycitin) (Kao and Chen 2006). Several epidemiological and intervention studies have shown an inverse relationship between consumption of soy foods and incidence of chronic diseases (Ikeda et al. 2006). The functional properties of soy isoflavones on immunity and oxidative stress were investigated (Ryan-Borchers et al. 2006) wherein, soymilk and supplemental isoflavones modulate B cell populations and appear to be shielding against DNA damage in postmenopausal women. Similarly, earlier studies reported that isoflavones from soybean influence the thyroid function in healthy adults and hypothyroid patients (Messina and Redmond 2006).

Earlier reports on isoflavone content of four commercially grown Indian varieties, demonstrated predominance of the malonylglucoside forms, followed by the glucosides, the aglycones, and the acetylglucosides (Sakthivelu et al. 2008; Devi et al. 2009). However, a comprehensive study on isoflavones content of more varieties of soybean is required as this would be helpful to select apposite soybean variety for greater health benefits for humans. In case of vegetable type soybean, fresh green beans are eaten shortly after they reach the green mature stage, which is considered a rich source of protein with acceptable taste (Shurtleff and Aoyagi 2009). As its cultivation is picking up, it is essential to find its isoflavones profile for wider acceptance from consumers. With this viewpoint, the aim of the present study was to screen 21 soybean varieties of Indian for isoflavone content. Apart from this, isoflavones in different growth stages of selected varieties were also profiled.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Authentic standards of daidzin, glycitin, genistin, daidzein, glycitein, genistein, trichloroacetic acid (TCA), dithiothreitol and mercaptoethanol were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich, Bangalore. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade methanol, acetonitrile, HCl and acetic acid were purchased from Rankem Laboratories (Mumbai, India). Deionized water from Milli-Q (Millipore Co., Bangalore, India) was used for all extraction and quantification purposes. All the chemicals were purchased from commercial sources (i.e., SRL chemicals and Rankem Chemical Laboratories, Bangalore) and glassware from Borosil, Mumbai, India.

Source of plant material

Certified Glycine max varieties were procured from Gandhi Krishi Vigyan Kendra (GKVK), University of Agricultural Sciences, Bangalore, Karnataka, India during 2012–2013 which were freshly harvested in the corresponding season (which were plotted in the same geographical location). Varieties include, twenty yellow type namely, NRC 76, MAUS 61, MACS 1184, RKS_45, MACS_450, NRC 77, KB 79 (Sneh), MACS_1039, KHSb-2, Bragg, DS 2410, MACS_1188, RKS_18, Hardee, MAUS-2, MAUS 417, MACS_1140, AMS_1, DS_2613 and JS 335 and one vegetable type named Karunae variety. All the varieties selected in the study were based on the planting location, variety dominance and seed maturity. The morphological characteristics of procured seeds were depicted in supplementary Fig. 1. Besides, the physical parameters of soybean seeds such as shape, coat color and luster, hilum color, seed weight (100 numbers), seed circumference as well as moisture content were documented. The moisture content was estimated as per the procedure of AOCS official methods (AOCS 2011).

All the twenty-one soybean varieties were surface sterilized with 0.1% sodium hypochlorite (v/v) for 20 min and rinsed four times with double-deionised water prior to analysis of isoflavones. Followed by analysis, the seeds of selective varieties were then imbibed in double-deionised water for 1 h and then sown in pots containing 6 kg of air-dried red silt loam (fine-silty) at 2-cm depth for germination. The seed growth stages from seed development to matured seeds, R5–R8 (50–88 days after flowering—DAF) were collected from selected varieties (Supplementary Table 1) for analyzing isoflavones content.

Isoflavones extraction and analysis

The soybean isoflavones were extracted using a minor modified method (Sakthivelu et al. 2008). Two grams of ground soybean seed with the seed coat was mixed with 2 mL of 0.1 N HCl and 10 mL of acetonitrile (ACN) in a 125 mL screw-top flask, stirred for 2 h at room temperature, and filtered through a Whatman no. 42 filter paper. The filtrate was dried in a vacuum rotary evaporator at a temperature below 30 °C and then redissolved in 10 mL of 80% HPLC grade methanol in distilled water. The redissolved sample was filtered through a 0.45 μm filter unit (Cameo 13 N syringe-filter, nylon) and then transferred to 1 mL vials.

HPLC Analysis

The High-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis was conducted following the method (Sakthivelu et al. 2008). The Shimadzu LC 20-AD HPLC equipped with a dual pump and a UV detector (model SPD-10A) was used to separate, identify, and quantify isoflavones.

Separation of isoflavones was achieved by a Bondapak C18 reversed phase HPLC column (150 mm × 4.6 mm and 5 μm internal diameter), and the samples were injected using a Rheodyne 7125 injector. A linear HPLC gradient was used with solvent A (0.1% glacial acetic acid and 5% acetonitrile in water) and solvent B (0.1% glacial acetic acid in acetonitrile). Succeeding the injection of 20 μL of the sample, solvent B was initiated from 10 to 14% B over 10 min, then increased to 20% over 2 min, maintained at 20% for 8 min continued to increase to 70% over 10 min, maintained at 70% for 3 min and then returned to 10% at the end of the 34 min running time. The flow rate of the solvent was 1 mL/min. The wavelength of the UV detector was set at 260 nm. Solvent ratios were expressed on a volume basis.

Standard solutions and calibration curves

Standards namely malonyl daidzin, malonyl genistin, malonyl glycitin, acetyl daidzin, acetyl genistin, and acetyl glycitin were isolated and purified using the modified method (Wang and Murphy 1994). The 12 reference compounds were chromatographed alone and in mixtures. All 12 isoflavones were identified by their retention times and co-chromatography with standard compounds, and the individual concentrations were calculated on the basis of each peak area. Calibration curves were obtained for each standard with high linearity (r > 0.995), by plotting the standard concentration as a function of the peak area obtained from HPLC analyses with 10 µL injections. Triplicate injections were analysed for each concentration of respective standard.

Identification and confirmation by Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrophotometer

Separation of isoflavones was achieved by a Sunfire C18 reversed phase HPLC column (250 mm × 4.6 mm and 5 μm internal diameter). The mobile phase for the separation of isoflavone extracts contains 0.1% formic acid (v/v) in water (Solvent A) and 0.1% formic acid (v/v) in acetonitrile (Solvent B). The linear gradient elution was from 10 to 35% of solvent B in 40 min with flow rate of 0.8 mL/min and wavelength for UV detection was 260 nm.

Identification and quantification of isoflavones extracts were done by using HPLC–MS system (Wu et al. 2004). This system consists of Waters Alliance 2695 HPLC equipped with a Q-TOF Ultima™ mass spectrometer and an auto-sampler coupled with photodiode array detector from Waters Corporation, Manchester, UK. The electrospray ion mass spectrophotometer (ESI–MS) interfaced were operated positive ion mode. The spectra were scanned within the mass range (m/z) of 200–600. Detection of MS was performed under collision energy level of 80%; needle voltage of 3.5 kV; the capillary temperature at 325 °C; helium as nebulizer at 40 psi and high-purity nitrogen (99.99%) as dry gas with flow rate of 8 L/min. Column compartment was set at 25 °C. The isolation width was set as 1.0 m/z. The calibration curves were plotted using a 1/x-weighted quadratic model for the regression of peak area ratio of analyte/internal standard acquired from UV and MS detector versus analyte concentration. Quality control (QC) samples were then prepared by diluting separate analyte stock solutions with diluent and spiking with the same amount of known internal standard. The concentrations of the QC and hydrolyzed soy samples were calculated from these linear equations.

Statistical analysis

Isoflavone analysis of each variety by HPLC was performed in triplicates with two extracts in each variety. The data were analyzed statistically by SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS Inc. South Wacker Drive, Chicago, USA) using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and the difference between the means of sample was analyzed by the least significant difference (LSD) test at a probability level of 0.05.

Results and discussion

Morphological characterization of soybean varieties

In the present investigation, the morphological characteristics of procured soybeans were documented prior to the analysis of isoflavones (Supplementary Fig. 1). Soybean varieties were classified on the basis of the qualitative characters such as shape, coat color and lusture, hilum color, 100 number of seeds weight and seed circumference respectively (Table 1). Seed shape of different varieties was varied from spherical, spherical-flattened and elongated-flattened. The coat color of seed varieties was grouped as yellow to green. Soy seed varieties differed in their seed coat luster and were classified from intermediate to shiny. The color of hilum in soybean varieties was assembled as green, yellow, brown, black, light brown and black.

Table 1.

Physical parameters of Glycine max varieties selected in the present study

| S. no | Sample name | Seed shape | Seed coat color | Seed coat lusture | Hilum color | Weight of 100 seeds(g)* | Seed circumference (cm3)* | Moisture content %* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Karunae | Spherical | Green | Intermediate | Green | 31.40 ± 0.24a | 0.667 ± 0.03a | 6.28 ± 0.08j |

| 2 | NRC 76 | Spherical | Yellow | Shiny | Black | 13.51 ± 0.13f | 0.118 ± 0.02e | 7.53 ± 0.09e |

| 3 | MAUS 61 | Spherical flattened | Yellow | Intermediate | Brown | 11.46 ± 0.18j | 0.10 ± 0.01f | 7.39 ± 0.06f |

| 4 | MACS 1184 | Spherical flattened | Dark yellow | Shiny | Light brown | 12.05 ± 0.12i | 0.10 ± 0.01f | 7.38 ± 0.05fg |

| 5 | RKS_45 | Spherical flattened | Yellow | Shiny | Black | 12.41 ± 0.22hi | 0.10 ± 0.01f | 7.49 ± 0.07e |

| 6 | MACS_450 | Spherical flattened | Yellow | Shiny | Black | 12.07 ± 0.16i | 0.11 ± 0.01e | 7.51 ± 0.10ef |

| 7 | NRC 77 | Spherical flattened | Yellow | Intermediate | Black | 14.17 ± 0.14ef | 0.12 ± 0.01d | 7.24 ± 0.09h |

| 8 | KB 79 | Spherical flattened | Dark yellow | Intermediate | Yellow | 12.94 ± 0.17g | 0.10 ± 0.02f | 6.01 ± 0.05k |

| 9 | MACS_ 1039 | Spherical flattened | White | Shiny | Brown | 12.46 ± 0.11h | 0.105 ± 0.01f | 7.90 ± 0.09c |

| 10 | KHSb- 2 | Spherical flattened | Dark yellow | Intermediate | Black | 10.96 ± 0.11k | 0.085 ± 0.003k | 7.72 ± 0.12d |

| 11 | Bragg | Spherical flattened | Dark yellow | Intermediate | Black | 15.01 ± 0.17d | 0.125 ± 0.02de | 8.38 ± 0.13a |

| 12 | DS 2410 | Elongated flattened | Yellow | Intermediate | Light black | 14.28 ± 0.23e | 0.13 ± 0.02c | 7.27 ± 0.09gh |

| 13 | MACS-_1188 | Elongated flattened | Yellow | Shiny | Black | 14.14 ± 0.12ef | 0.12 ± 0.02de | 7.70 ± 0.08d |

| 14 | RKS_18 | Elongated flattened | Yellow | Intermediate | Black | 11.75 ± 0.11j | 0.10 ± 0.01f | 8.05 ± 0.11b |

| 15 | Hardee | Elongated flattened | Dark yellow | Intermediate | Brown | 16.18 ± 0.18b | 0.145 ± 0.02b | 6.67 ± 0.07i |

| 16 | MAUS-2 | Elongated flattened | Dark yellow | Intermediate | Brown | 15.85 ± 0.14c | 0.13 ± 0.01cd | 7.78 ± 0.09d |

| 17 | MAUS 417 | Elongated flattened | Light yellow | Intermediate | Light brown | 13.18 ± 0.12g | 0.12 ± 0.01cd | 7.26 ± 0.06gh |

| 18 | MACS _1140 | Spherical | Yellow | Shiny | Black | 15.02 ± 0.13d | 0.13 ± 0.01bc | 7.91 ± 0.08c |

| 19 | AMS_1 | Spherical flattened | Yellow | Intermediate | Brown | 9.66 ± 0.08l | 0.085 ± 0.002k | 7.36 ± 0.07fg |

| 20 | DS_2613 | Spherical | Yellow | Shiny | Black | 13.98 ± 0.15ef | 0.12 ± 0.01d | 7.30 ± 0.06g |

| 21 | JS 335 | Spherical | Yellow | Shiny | Black | 14.88 ± 0.12d | 0.14 ± 0.01b | 7.82 ± 0.11cd |

*Means with different superscripts are significantly different from each other as analyzed by Duncan’s multiple range test at p ≤ 0.05. Each value represents the mean ± SD obtained from four independent measurements

In addition to this, the seed circumference (cm3) and weight of the 100 seeds (gm) were calculated. Highest seed circumference was observed for green type, Karunae (0.667 cm3) followed by Hardee (0.145 cm3) and lowest in KHSb-2 and AMS_1 (0.085 cm3). Significant variation in one hundred seeds weight was observed amongst the soybean varieties. Vegetable type Karunae has a highest seed weight (31.40 g) followed by Hardee (16.18 g) and the mean seed weight of the twenty varieties except vegetable type were 13.29 g. Moisture content generally declines in the mature seeds, however in the selected varieties the moisture content was high as in case of Bragg (8.38%) and the lowest in KB 79 (6.01%).

Soybean seeds when introduced for commercial cultivation, there might be the absence of consistency among seeds for different highlights even under the known arrangement of ecological conditions. As investigated by several studies, an attempt was performed in the present study to characterize the morphological and physical parameters in soybean varieties (Kumawat et al. 2015). The observations for seed size and weight especially for green vegetable type Karunae was in agreement with notes who documented wide range of characteristic features of soybeans (Shurtleff and Aoyagi 2009).

Isoflavone analysis

Screening of isoflavone contents in twenty-one soybean varieties was determined using HPLC (Table 2). A representative HPLC chromatogram of isoflavones and standards in soybean varieties was depicted (Figs. 1, 2). All the isoflavones (aglycones, glucosides, malonyl glucosides and acetyl glucosides) except glycitein were separated and identified successfully using the applied HPLC conditions.

Table 2.

Concentration of different forms of isoflavones from seed extracts of soybean varieties (micrograms per gram of dry weight)a

| Varietya | Daidzein family | Glycitein family | Genistein family | TI | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Din | MDin | ADin | Dein | TDein | Gly | MGlyn | AGlyn | Glyein | TGlyein | Gin | MGin | AGin | Gein | TGein | ||

| Karunae | 5.7f | 22.1h | 0.7f | 1.7h | 30.2h | 19.7c | 28.8bc | 0.1e | nd | 50.3bc | 8.6f | 50.6h | 0.4ef | 0.8f | 60.5h | 140.9h |

| NRC 76 | 17.1ef | 60.8fh | 2.3e | 4.4f | 84.8fh | 5.7f | 8.2f | 0.5de | nd | 14.4f | 21.7ef | 119.6fh | 0.3f | 3.7ef | 145.4fh | 244.7fh |

| MAUS 61 | 18.6ef | 73.4f | 1.4ef | 7.6ef | 101.1f | 6.7ef | 9.6ef | 0.6d | nd | 16.9e | 22.1ef | 141.2fh | 0.4ef | 4.3e | 168.1fh | 286.2f |

| MACS 1184 | 34.4e | 134.3ef | 4.2cd | 9.2ef | 182.2ef | 11.8e | 17.3e | 1.1cd | nd | 30.1de | 42.5de | 250.2f | 2.3d | 3.9ef | 299.0f | 511.4ef |

| RKS_45 | 42.8de | 164.6de | 3.4de | 11.8e | 222.6e | 22.8b | 32.6ab | 2.0c | nd | 57.7ab | 47.1d | 340.3ef | 0.9e | 7.2de | 395.6ef | 675.8e |

| MACS_450 | 63.9bc | 206.1cd | 5.5c | 11.6e | 287.3cd | 18.3cd | 25.7cd | 1.6cd | nd | 45.3cd | 59.4c | 409.7de | 4.2c | 12.4bc | 485.6de | 818.3d |

| NRC 77 | 72.2bc | 218.9bc | 7.7ab | 19.3b | 298.8c | 19.5c | 23.9de | 1.9cd | nd | 45.5cd | 65.4bc | 419.1e | 5.4bc | 12.5bc | 502.5d | 846.9cd |

| KB-79 | 44.5d | 223.8bc | 5.8bc | 16.1bc | 290cd | 17.2d | 25.7bc | 1.3cd | nd | 44.2cd | 56.4cd | 425.2b | 2.9cd | 9.7cd | 494.2de | 828.4cd |

| MACS 1039 | 67.6bc | 207.2cd | 5.6bc | 12.04de | 292.4cd | 21.9bc | 24.8d | 2.5b | nd | 49.2c | 62.6bc | 408.4de | 6.3ab | 13.6ab | 491.0de | 832.6cd |

| KHSb 2 | 54.8cd | 230.2b | 6.1bc | 17.8bc | 309.0bc | 24.0ab | 33.3a | 2.3bc | nd | 59.6ab | 63.6bc | 439.3cd | 7.1a | 6.9de | 517.0cd | 885.6cd |

| Bragg | 37.1e | 177.4de | 3.5de | 13.6d | 246.2de | 18.1cd | 25.8cd | 2.2bc | nd | 45.4cd | 52.9cd | 372.4ef | 1.1de | 11.0c | 432.8e | 724.3de |

| DS_2410 | 84.3d | 207.7cd | 6.2bc | 16.7bc | 314.9bc | 22.7b | 29.0b | 2.8ab | nd | 55.3ab | 76.7ab | 435.2cd | 6.6ab | 11.7bc | 530.4cd | 898.7c |

| MACS_1188 | 96.6a | 203.6cd | 3.2de | 15.3c | 318.6bc | 21.8bc | 29.5b | 2.7ab | nd | 54.3b | 68.6bc | 449.8c | 5.7bc | 13.4ab | 537.6cd | 910.5bc |

| RKS_18 | 90.8ab | 216.2bc | 6.5b | 18.5bc | 332.1b | 21.2bc | 26.1c | 2.2bc | nd | 49.8bc | 77.1ab | 470.8bc | 6.1ab | 11.9bc | 566.0bc | 948.1bc |

| Hardee | 36.4e | 141.2e | 5.4c | 12.9de | 195.9ef | 12.1de | 19.3de | 1.5cd | nd | 33.0de | 37.2cd | 281.4ef | 2.6d | 8.2d | 329.4ef | 558.2ef |

| MAUS-2 | 60.8bc | 266.4a | 8.5a | 23.5a | 359.3a | 26.6a | 32.8ab | 3.0a | nd | 62.4a | 87.0a | 518.1a | 6.8ab | 15.0a | 627.0a | 1048.6a |

| MAUS 417 | 91.9ab | 223.5bc | 4.7cd | 22.5ab | 342.7ab | 21.1bc | 27.7bc | 2.7ab | nd | 52.8bc | 69.4bc | 471.2bc | 6.0b | 10.3cd | 556.7c | 953.3b |

| MACS 1140 | 83.3b | 243.0ab | 2.4e | 19.4b | 348.3ab | 24.6ab | 30.2ab | 2.9ab | nd | 57.6ab | 70.6b | 474.1b | 5.9bc | 10.9cd | 561.4bc | 967.3ab |

| AMS_1 | 58.7c | 252.3ab | 7.4ab | 22.4ab | 340.8ab | 25.4ab | 31.4ab | 2.6ab | nd | 59.4ab | 81.7ab | 498.4ab | 6.4ab | 12.6bc | 599.2b | 999.4ab |

| DS_2613 | 49.3cd | 254.5ab | 6.9ab | 23.1a | 340.1ab | 21.0c | 28.4bc | 2.7ab | nd | 52.2bc | 82.4ab | 500.2ab | 6.5ab | 13b | 616.1ab | 1008.4ab |

| JS 335 | 38.6e | 212.8c | 3.9d | 15.0c | 270.4d | 15.7de | 23.3de | 0.5de | nd | 39.6d | 51.2cd | 382.0e | 1.1de | 9.3cd | 443.6de | 753.5de |

| Average | 54.7cd | 187.6d | 4.8cd | 14.9cd | 262.2de | 18.9cd | 25.4cd | 1.9cd | nd | 46.4cd | 57.3cd | 374.1ef | 4.0c | 9.6cd | 445.6de | 754.3de |

aDin daidzin, Mdin malonyl daidzin, Adin acetyl daidzin, Dein daidzein, TDin total daidzein, Glyn glycitin, Mglyn malonyl glycitin, Aglyn acetyl glycitin, Glyein glycitein, TGlyin total glycitein, Gin genistin, Mgin malonyl genistin, Agin acetyl genistin, Gein genistein, TGin total genistein, TI total isoflavone; nd not detected. Different letters are significant among cultivars (p < 0.05)

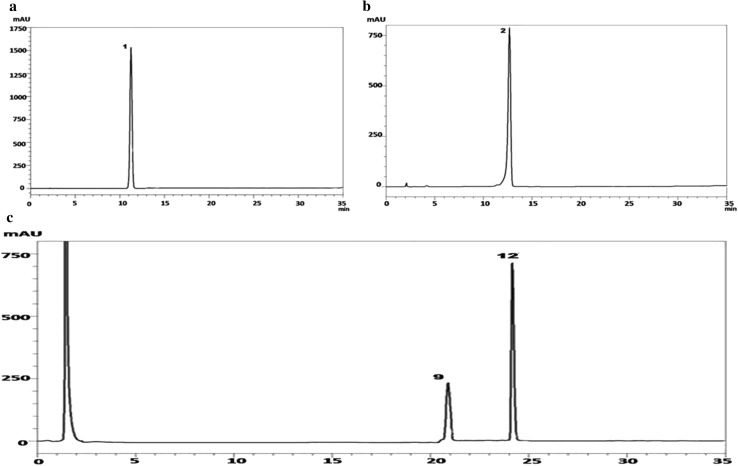

Fig. 1.

Representative HPLC chromatogram of isoflavones in soybean. 1, Daidzin; 2, glycitin; 3, genistin; 4, malonyldaidzin; 5, malonylglycitin; 6, acetyldaidzin; 7, acetylglycitin; 8, malonylgenistin; 9, daidzein; 10, glycitein; 11, acetylgenistin; 12, genistein

Fig. 2.

HPLC chromatogram of standard isoflavones A. 1, daidzin; B. 2, glycitin; C. 9, daidzein; 12, genistein

In the present study, the total isoflavone (TI) content was found within a wide range of 140.9–1048.6 μg/g of soy in different varieties. Of twenty-one soybean varieties, the highest isoflavone content was found in MAUS-2 (Table 2) followed by DS_2613 and lowest in Karunae (140.9 μg/g of soy). The average total isoflavone content of soybean varieties was 754.32 μg/g of soy and this is considerably lower than those reports achieved in Serbia (Malenčić et al. 2012). The vegetable-type soybean variety (Karunae) has the lowest TI content which, corresponds with the report (Mebrahtu et al. 2004).

The total isoflavone content in yellow soybean seeds is reported to be highest compared to black and green seed varieties (Kim et al. 2006; Kumar et al. 2010; Malenčić et al. 2012) and similar observations were found in the present investigation. Significant differences in the isoflavone content were observed for all the aglycones and their glucoside conjugates as well as total daidzein, total genistein, total glycitein, and total isoflavone (p < 0.05).

Among the isoflavone family, MAUS-2 variety contains the highest daidzein (359.3 μg/g of soy), glycitein (62.4 μg/g of soy) and genistein (627.0 μg/g of soy) respectively. Also, amid the three types of isoflavones derivatives, the level of genistein derivatives was highest followed by derivatives of daidzein and glycitein, which were 59, 36, and 5% of total isoflavone, respectively. In similar to other studies, of the 12 studied isoflavones, malonyl genistin content was the highest, followed by malonyl daidzin and genistin (Table 2), while genistein present at the lowest level (Sakthivelu et al. 2008). The isoflavone levels in the four isoflavone groups increased in the following order: malonylglucoside >glucoside >aglycone >acetylglucoside. Similarly, the 0.1% acetic acid based extraction followed by HPLC analysis revealed the presence of higher content of malonyl glucosides conjugate types compared to isoflavone types (Zhang et al. 2014). A significant correlation observed for malonylglucoside (r = 0.99, p = 0.001), TGin (r =0.99, p =0.001), and TDin (r = 0.91, p = 0.001) with total isoflavone content, whereas acetylglucoside and aglycone were not correlated extensively with the total isoflavone.

Numerous factors influence the isoflavone content in the soybean varieties: growth stage, planting location, variety, cropping year, climate, country of origin, and seed weight etc., and all factors might contribute for alteration in the isoflavone levels in soy varieties (Riedl et al. 2007; Sakthivelu et al. 2008; Saini et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2014). Similarly, major differences in the levels of individual isoflavones were observed within the three soybean cultivars viz., Hrvatica, Lea, Danica from Croatia, wherein, TI content ranged from 80.7 to 213.6 mg/100 g of soybean, with genistein as the most abundant isoflavone (Mujić et al. 2011).

In contrast, no significant difference for genistin levels was recorded within four Kansas soybean cultivars viz., KS4202, KS4302sp, KS4402sp, and KS 4702sp, however, a two and threefold difference for daidzin and glycitin, respectively were reported (Swanson et al. 2004). Especially seasonal fluctuations are periodical series and have an impact on the availability of active principles in various plants, especially glycosides, polyphenol, flavonoids, alkaloids etc. However, there is no general rule for the harvesting time for better yield of specific secondary metabolites (Soni et al. 2015).

Analysis of isoflavones during ontogeny in soybean

Selected soybean varieties such as JS 335 (popular, seed yield (2678 kg/ha), widely cultivated) and MAUS-2 (high isoflavone content) were germinated under greenhouse conditions. Seeds were collected during the seed growth stages specifically from seed development to maturity stage R5–R8 i.e. 55–80 DAF (Supplementary Table 1).

The duration of each stage for each variety was mentioned in supplementary Table 1 and growth development stages were depicted in the supplementary Fig. 2. For evaluation of significant changes in the individual as well as total isoflavone content during seed ontogeny, R5 (e), R6, R7 (m) and R8 reproductive stages were selected. A positive correlation between total isoflavone content and growth stages was found during the progression of seed development (Table 3). This is in agreement with the results of Kim & Chung, who observed an increase of TI content during the growth transition stage (R5- R8) (Kim and Chung 2007).

Table 3.

Ioflavone concentration in growth stages of selected varieties (micrograms per gram of dry weight)a

| Varietya | Growth stage | Daidzein family | Glycitein family | Genistein family | TI | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Din | MDin | ADin | Dein | TDein | Gly | MGlyn | AGlyn | Glyein | TGlyein | Gin | MGin | AGin | Gein | TGein | |||

| JS 335 | R5 (e) | 7.09d | 70.1e | 0.7e | 2.7e | 80.6e | 8.4e | 4.2e | 0.09d | nd | 12.6e | 9.3d | 39.1e | 0.2d | 1.7d | 50.2e | 138.4e |

| R 6 | 14.5c | 84.1de | 1.4de | 5.6cd | 105.6de | 16.3bc | 24.1bc | 0.2cd | nd | 40.6bc | 19.2c | 143.7cd | 0.4cd | 3.5c | 166.9d | 283.6d | |

| R7 (m) | 23.7bc | 130.6c | 2.41cd | 9.2bc | 165.9c | 14.8cd | 22.7c | 0.3c | nd | 37.8cd | 31.4bc | 234.4bc | 0.6c | 5.7bc | 272.2c | 462.5c | |

| R8 | 38.6b | 212.7ab | 3.9bc | 15.0b | 270.3ab | 15.6c | 23.3bc | 0.5bc | nd | 39.5c | 51.1b | 381.9b | 1.1bc | 9.3b | 443.5b | 753.5b | |

| MAUS-2 | R5 (e) | 11.3cd | 96.9d | 1.5d | 4.3d | 114.2d | 10.9d | 6.1d | 0.6bc | nd | 17.6d | 16.2cd | 49.8d | 1.2bc | 2.8cd | 70.3de | 196.3de |

| R 6 | 21.8bc | 125.6cd | 3.0c | 8.4c | 158.8cd | 29.8a | 34.7a | 1.0b | nd | 65.5a | 31.2bc | 185.9c | 2.4b | 5.3bc | 225.0cd | 376.4cd | |

| R7 (m) | 45.3ab | 198.8b | 6.3b | 17.5ab | 267.9b | 23.5b | 24.4b | 1.9a | nd | 49.8b | 64.9ab | 386.6b | 5.0ab | 11.2ab | 467.8ab | 780.5ab | |

| R8 | 60.8a | 266.4a | 8.5a | 23.5a | 359.2a | 26.6ab | 32.7ab | 2.9ab | nd | 62.3ab | 86.9a | 518.1a | 6.8a | 15.0a | 626.9a | 1048.6a | |

aDin daidzin, Mdin malonyl daidzin, Adin acetyl daidzin, Dein daidzein, TDin total daidzein, Glyn glycitin, Mglyn malonyl glycitin, Aglyn acetyl glycitin, Glyein glycitein, TGlyin total glycitein, Gin genistin, Mgin malonyl genistin, Agin acetyl genistin, Gein genistein, TGin total genistein, TI total isoflavone; nd not detected. Different letters are significant among cultivars (p < 0.05)

An increase of 5.4-fold (from 138.4 to 753.5 μg/g dry weight (DW) basis) and 5.3-fold (from 196.3 to 1048.6 μg/g DW) of total isoflavone concentration was observed for JS 335 and MAUS-2 respectively, from R5 to R8 stage. In the R5 (e) stage (beginning seed), MAUS-2 had the maximum total isoflavone (196.3 μg/g), total daidzein (67.2 μg/g), total glycitein (11.6 μg/g) and total genistein (117.3 μg/g). However, JS 335 had the lowest level of total isoflavone (138.4 μg/g), total daidzein, total glycitein and total genistein. The same trend was observed in the R6, R7 and until complete maturity where the level of most of the isoflavones forms was highest in MAUS-2 than JS 335.

The R6 and R7 stage seed of MAUS-2, showed a rise of 2.8 and 1.3 fold TI in comparison to R8 matured seed. A maximum percentage of different isoflavone forms were between R5 and R6 stages compared to R7 stage and complete maturity (R8).

The malonylglucoside concentration was highest at each stage. The malonyldaidzin content (70.1 and 96.9 μg/g) was higher than malonylgenistin (39.1 and 49.8 μg/g) in JS 335 and MAUS-2 respectively at the R5 stage. This trend was inverse during the transition of growth stage from R6 to R7 where maximum malonylgenistin content was observed. These results were consistent with the earlier findings (Kim et al. 2005; Kim and Chung 2007). In both the varieties, glycitin content was high at R6 stage, but subsequently decreased (Kim and Chung 2007). As in matured seeds, the major forms of conjugated isoflavones were malonylglucosides, followed by glucosides, acetylglucosides, and aglycones at all the stages. The concentration of total glycitein was more at the R6 stage than matured seed (R8 stage). However, during maturity, the total genistein content was predominant than total daidzein and glycitein content. Significant correlation of malonylglucoside, glucoside and total isoflavone contents were found with the growth stages. Conversely, a negative correlation was observed for the acetylglucosides and aglycone content. As suggested by earlier reports, this difference might be due to variation in temperature in the growth stage Kim and Chung (2007).

Isoflavones identification in soybean seeds using LC–MS

After quantification of isoflavones in twenty-one varieties by HPLC, various isoflavone forms were identified by Liquid Chromatography-Electrospray positive Mass spectrophotometer (LC–ESI+ MS). A representative chromatogram for MS was presented (Fig. 3). The retention time, m/z, [M + H] + and typical fragment ions for individual peaks confirmed the presence of isoflavone forms in the soybean seeds. By comparing the retention time and mass spectrum with corresponding standards, two aglycones (daidzein and genistein), three glucosides (daidzin, genistin, and glycitin) and its acetyl and malonyl derivatives were identified.

Fig. 3.

Representative HPLC chromatogram of isoflavones in seed extract of soybean and confirmation by MS. 1, Daidzin; 2, Glycitin; 3, Genistin; 4, malonyldaidzin; 5, malonylglycitin; 6, acetyldaidzin; 7, acetylglycitin; 8, malonylgenistin; 9, daidzein; 10, acetylgenistin; 11, genistein

Earlier studies also pointed out the principal isoflavone forms, glucosides and its malonate and acetate derivatives (Wang and Sporns 2000; Wu et al. 2004). Generally, for all glucoside forms, at the 7/4′ position of aglycones, the glucosyl group is substituted whereas in case of acetyl/malonyl derivatives, acetyl/malonyl group is coupled to the sugar moiety (6′′ position) (Wu et al. 2004). On this basis, the structures were confirmed by their molecular ions and specific fragment ions. The molecular ions, m/z 417.88, 447.95, 433.81 and fragments correspond to the peaks 1, 2 and 3 respectively (Fig. 3). The MS spectra for glycosides (a) daidzin, (b) glycitin and (c) genistin were illustrated in supplementary Fig. 3. The mass spectra for malonyl glycosides were depicted in Fig. 5 as (a) malonyl daidzin, (b) malonyl glycitin and (c) malonyl genistin. The molecular ions of malonylglycosides, m/z 503.60, 532.52, 519.54 (supplementary Fig. 4) correlated with the peak 4, 5 and 8 (Fig. 3). The spectra with molecular ions for acetyl glucosides m/z 460.83, 489.94, 475.82 (supplementary Fig. 5) corresponds with the peaks 6, 7 and 11 respectively (Fig. 3). In case of aglycones, the mass spectra with m/z 255.27 and 271.23 in supplementary Fig. 6 corresponds to peak 9 (daidzein) and peak 11 (genistein) where glycitein was not detected in the sample extracts (Fig. 3).

Our earlier results also showed the absence of aglycone, glycitein in the sample extracts (Sakthivelu et al. 2008). Also, from the present investigation, the 11 isoflavone forms (except glycitein) were confirmed in the twenty-one varieties using LC/MS and with purified standards, and similar observations were reported for 30 soybean varieties (Wu et al. 2004).

Conclusion

HPLC analysis of isoflavones in 21 soybean varieties of India and isoflavone forms characterization by LC–ESI+ MS showed noteworthy differences in the isoflavone content for all the aglycones and their glucoside conjugates as well as total daidzein, total genistein, total glycitein, and total isoflavone. The average total isoflavone content of soybean varieties was found to be 754.32 μg/g of soybean with the highest isoflavone content in MAUS-2 followed by DS_2613 and lowest in Karunae. Genistein derivatives were in high content followed by derivatives of daidzein and glycitein, which were 59, 36, and 5% of total isoflavone, respectively. A positive correlation of total isoflavone content and growth stages was found during the progression of seed development. The profiling of soybean isoflavone content aids in understanding the regulation of isoflavone biosynthesis for better crop resistance to disease and greater health benefits for humans. Overall, the present investigation demonstrated the superiority of certain soybean varieties and it will be having a wide range of applications in the food industry in terms of nutraceutical perspective.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgment

This work was financed under Project No. MLP 114/2012-2014 from Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, New Delhi, India. MKAD is thankful to CSIR, New Delhi for the senior research fellowship.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest, in terms of scientific, financial and personal.

References

- AOCS . Moisture content, Da 2a-48. In: Firestone, editor. Official methods and recommended practices of the American Oil Chemical Society. 3. Champaign, IL: AOCS Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes S. The biochemistry, chemistry and physiology of the isoflavones in soybeans and their food products. Lymphat Res Biol. 2010;8:89–98. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2009.0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell T, Cohick W, Raskin I. Dietary phytoestrogens and health. Phytochem. 2004;65:995–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devi MKA, Gondi M, Sakthivelu G, Giridhar P, Rajasekaran T, Ravishankar GA. Functional attributes of soybean seeds and products, with reference to isoflavone content and antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2009;114:771–776. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RA. Phytoestrogens. Ann Rev Plant Biol. 2004;55:225–261. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA (1999) FDA approves new health claim for soy protein and coronary heart disease. FDA Talk Paper http://www.Fda.gov/bbs/topics/ANSWERS/ANS00980.html. Accessed 26 Sept 2015

- Franke AA, Custer LJ, Cerna CM, Narala KK. Quantitation of phytoestrogens in legumes by HPLC. J Agric Food Chem. 1994;42:1905–1913. doi: 10.1021/jf00045a015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Izquierdo A, Penalvo JL, Gil JI, Medina S, Horcajada MN, Lafay S, Silberberg M, Llorach R, Zafrilla P, Garcia-Mora P. Soy isoflavones and cardiovascular disease epidemiological, clinical and-omics perspectives. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012;13:624–631. doi: 10.2174/138920112799857585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham TL. Flavonoid and isoflavonoid distribution in developing soybean seedling tissues and in seed and root exudates. Plant Physiol. 1991;95:594–603. doi: 10.1104/pp.95.2.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasanah Y, Nisa TC, Armidin H, Hanum H. Isoflavone content of soybean [Glycine max (L). Merr.] cultivars with different nitrogen sources and growing season under dry land conditions. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2010;122:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- He J, Wang S, Zhou M, Yu W, Zhang Y, He X. Phytoestrogens and risk of prostate cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:231–242. doi: 10.1186/s12957-015-0648-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda Y, Iki M, Morita A, Kajita E, Kagamimori S, Kagawa Y, Yoneshima H. Intake of fermented soybeans, natto, is associated with reduced bone loss in postmenopausal women: Japanese Population-Based Osteoporosis (JPOS) Study. J Nutr. 2006;136:323–1328. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.5.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isanga J, Zhang GN. Soybean bioactive components and their implications to health—a review. Food Rev Int. 2008;24:252–276. doi: 10.1080/87559120801926351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kao TH, Chen BH. Functional components in soybean cake and their effects on antioxidant activity. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:7544–7555. doi: 10.1021/jf061586x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur M, Badhan RK. Phytoestrogens modulate breast cancer resistance protein expression and function at the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;18:132–154. doi: 10.18433/J3P31K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Chung I. Change in isoflavone concentration of soybean (Glycine max L.) seeds at different growth stages. J Sci Food Agric. 2007;87:496–503. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2743. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Chen F, Wang X, Rajapakse NC. Effect of chitosan on the biological properties of sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:3696–3701. doi: 10.1021/jf0480804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SL, Berhow MA, Kim JT, Chi HY, Lee SJ, Chung IM. Evaluation of soya saponin, isoflavone, protein, lipid, and free sugar accumulation in developing soybean seeds. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:10003–10010. doi: 10.1021/jf062275p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuligowski M, Pawłowska K, Jasińska-Kuligowska I, Nowak J. Isoflavone composition, polyphenols content and antioxidative activity of soybean seeds during tempeh fermentation. CYTA J Food. 2017;15:27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Rani A, Dixit AK, Pratap D, Bhatnagar D. A comparative assessment of total phenolic content, ferric reducing-anti-oxidative power, free radical-scavenging activity, vitamin C and isoflavones content in soybean with varying seed coat colour. Food Res Int. 2010;43:323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2009.10.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumawat G, Singh G, Gireesh C, Shivakumar M, Arya M, Agarwal DK, Husain SM. Molecular characterization and genetic diversity analysis of soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) germplasm accessions in India. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2015;21:101–107. doi: 10.1007/s12298-014-0266-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MM, Gomez SL, Chang JS, Wey M, Wang RT, Hsing AW. Soy and isoflavone consumption in relation to prostate cancer risk in China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:665–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenčić D, Kevrešan S, Popović M, Štajner D, Popović B, Kiprovski B, Djurić S. Cholic acid changes defense response to oxidative stress in soybean induced by Aspergillus niger. Open Life Sci. 2012;7:132–137. [Google Scholar]

- Mebrahtu T, Mohamed A, Wang C, Andebrhan T. Analysis of isoflavone contents in vegetable soybeans. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2004;59:55–61. doi: 10.1007/s11130-004-0023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina M, Redmond G. Effects of soy protein and soybean isoflavones on thyroid function in healthy adults and hypothyroid patients: a review of the relevant literature. Thyroid. 2006;16:249–258. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.16.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujić I, Šertović E, Jokić S, Sarić Z, Alibabić V, Vidović S, Živković J. Isoflavone content and antioxidant properties of soybean seeds. Croatian J Food Sci Technol. 2011;3:16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Panat NA, Maurya DK, Ghaskadbi SS, Sandur SK. Troxerutin, a plant flavonoid, protects cells against oxidative stress induced cell death through radical scavenging mechanism. Food Chem. 2016;194:32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedl KM, Lee JH, Renita M, St Martin SK, Schwartz SJ, Vodovotz Y. Isoflavone profiles, phenol content, and antioxidant activity of soybean seeds as influenced by cultivar and growing location in Ohio. J Sci Food Agric. 2007;87:1197–1206. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan-Borchers TA, Park JS, Chew BP, McGuire MK, Fournier LR, Beerman KA. Soy isoflavones modulate immune function in healthy postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1118–1125. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.5.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saini RK, Devi MKA, Giridhar P, Ravishankar GA. Augmentation of major isoflavones in Glycine max L. through the elicitor-mediated approach. Acta Bot Croatica. 2013;72:311–322. doi: 10.2478/v10184-012-0023-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sakthivelu G, Devi MKA, Giridhar P, Rajasekaran T, Ravishankar G, Nikolova M, Angelov G, Todorova R, Kosturkova G. Isoflavone composition, phenol content, and antioxidant activity of soybean seeds from India and Bulgaria. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:2090–2095. doi: 10.1021/jf072939a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shurtleff W, Aoyagi A. History of Edamame, green vegetable soybeans, and vegetable-type soybeans (1275–2009): extensively annotated bibliography and source book. Lafayette, CA: Soyinfo Centre; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Soni U, Brar S, Gauttam VK. Effect of seasonal variation on secondary metabolites of medicinal plants. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2015;6:3654–3662. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson M, Stoll M, Schapaugh W, Takemoto L. Isoflavone content of Kansas Soybeans. Am J Undergrad Res. 2004;2:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Teekachunhatean S, Hanprasertpong N, Teekachunhatean T. Factors affecting isoflavone content in soybean seeds grown in Thailand. Int J Agric. 2013;2013:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Murphy PA. Isoflavone content in commercial soybean foods. J Agric Food Chem. 1994;42:1666–1673. doi: 10.1021/jf00044a016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Sporns P. MALDI-TOF MS analysis of isoflavones in soy products. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:5887–5892. doi: 10.1021/jf0008947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardhani DH, Vázquez JA, Pandiella SS. Kinetics of daidzin and genistin transformations and water absorption during soybean soaking at different temperatures. Food Chem. 2008;111:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.03.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Wang M, Sciarappa WJ, Simon JE. LC/UV/ESI-MS analysis of isoflavones in edamame and tofu soybeans. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:2763–2769. doi: 10.1021/jf035053p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu O, McGonigle B. Metabolic engineering of isoflavone biosynthesis. Adv Agron. 2005;86:147–190. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2113(05)86003-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Ge Y, Han F, Li B, Yan S, Sun J, Wang L. Isoflavone content of Soybean cultivars from maturity group 0 to VI grown in northern and southern China. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2014;91:1019–1028. doi: 10.1007/s11746-014-2440-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.