Abstract

This study uses American Board of Surgery data to assess the association between maintainence of certification in general surgery and loss-of-license actions after expiration of the initial 10-year certification among general surgeons.

Time-limited board certification was implemented to ensure that physicians maintain competence.1 Maintaining board certification typically requires examination preparation and compliance with other requirements; however, the evidence linking maintenance of certification with outcomes has been mixed.1,2,3,4,5

We hypothesized that maintaining certification might serve as an indicator of responsible professional behavior and be inversely related to loss-of-license actions by state medical boards.

Methods

General surgeons’ initial certification data were collected from the American Board of Surgery (surgeons with additional certifications were excluded) from 1976 through 2005. Disciplinary actions implemented by state medical licensing boards were obtained from the Disciplinary Action Notification System through the American Board of Medical Specialties from 1976 through 2016.

We analyzed loss-of-license actions after the expiration of the initial 10-year certification. Surgeons grant permission to use deidentified data for research purposes on enrollment in the certification program. The Pearl institutional review board determined this study was exempt.

Recertification status was categorized as on-time recertification (passed the recertification examination prior to expiration of the initial 10-year certification), lapsed recertification (passed the recertification examination after the expiration of the initial 10-year certification), and not recertified. We analyzed recertification status only at the expiration of the initial certification (ie, we did not analyze subsequent recertification cycles). However, loss-of-license actions were analyzed up to 30 years after expiration of the initial certification.

Surgeons with a disciplinary action within the first 10 years of initial certification were excluded in case an action caused them to lapse or not recertify. Surgeon characteristics included sex, graduation from a US or international medical school, and the number of attempts to pass both the general surgery written qualifying and oral certifying examinations for initial certification.

We used χ2 analyses to compare surgeon characteristics, incidence rates (IRs) to compare loss-of-license actions while accounting for exposure using 1000 person-years at risk, and Cox proportional regression (hazards ratios [HRs]) to compare the IRs with a 2-sided α level of .05. Lapsed recertification was treated as a time-dependent variable (the lapsed recertification group was treated as not recertified until they recertified). We used R statistical software version 3.5 and the survival and survminer packages (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

The sample included 15 500 surgeons (13 048 in the on-time recertification group, 1045 in the lapsed recertification group, and 1407 in the not recertified group; Table). Compared with surgeons in the on-time recertification group, surgeons in the lapsed recertification group were more likely to be male and those in the lapsed recertification or not recertified groups were more likely to be international medical graduates. Surgeons in the on-time recertification group required significantly fewer attempts to pass both the qualifying and certifying examinations than those in the lapsed recertification or not recertified groups.

Table. Demographic Characteristics and Loss-of-License Incidence Rates Among Surgeon Recertification Groups (N = 15 500)a.

| Characteristics | On-Time Recertification (n = 13 048) |

Lapsed Recertification (n = 1045)b |

Not Recertified (n = 1407) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, No. (%) | |||

| Male | 11 360 (87.1) | 965 (92.3) | 1235 (87.8) |

| Female | 1688 (12.9) | 80 (7.7) | 172 (12.2) |

| Location of medical school, No. (%) | |||

| United States | 10 992 (84.2) | 698 (66.8) | 904 (64.3) |

| International | 2056 (15.8) | 347 (33.2) | 503 (35.7) |

| Qualifying examination attempt, No. (%)c | |||

| Initial | 11 096 (85.0) | 781 (74.7) | 1033 (73.4) |

| >1 | 1796 (13.8) | 199 (19.0) | 282 (20.0) |

| Certifying examination attempt, No. (%)d | |||

| Initial | 10 446 (80.0) | 808 (77.3) | 1037 (73.7) |

| >1 | 2582 (19.8) | 237 (22.7) | 369 (26.2) |

| Person-years at risk | 196 356 | 18 027 | 29 531 |

| No. of loss-of-license actions | 188 | 46 | 47 |

| Loss-of-license actions, incidence rate (95% CI) per 1000 person-years | 0.96 (0.82-1.09) | 2.55 (1.81-3.29) | 1.59 (1.14-2.05) |

P < .001 for all comparisons based on χ2 analysis.

Treated as a time-dependent variable. This group had 3 incidents per 3423 person-years at risk prior to recertifying that were added to the incidents and person-years at risk for the not recertified group.

There were 92 missing records for the number of qualifying examination attempts.

There was 1 missing record for the number of certifying examination attempts.

Surgeons in the on-time recertification group had the lowest rate of loss-of-license actions (IR, 0.96 [95% CI, 0.82-1.09] per 1000 person-years) compared with surgeons in the lapsed recertification group (IR, 2.55 [95% CI, 1.81-3.29] per 1000 person-years) and surgeons in the not recertified group (IR, 1.59 [95% CI, 1.14-2.05] per 1000 person-years) (Table). The mean time for a lapsed surgeon to recertify was 3.28 years.

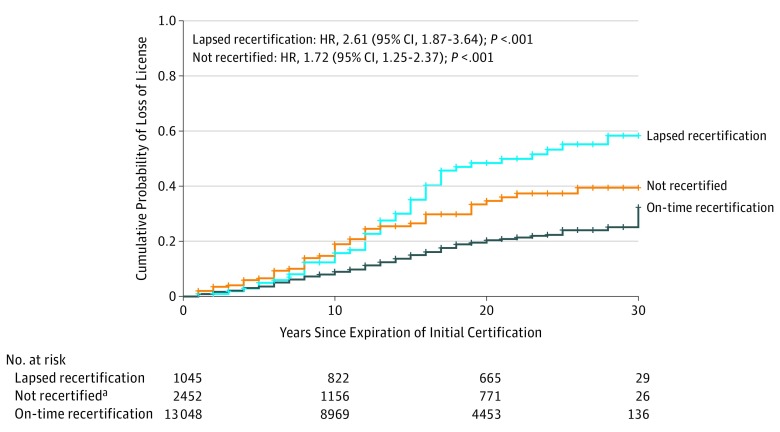

Surgeons in the lapsed recertification group (HR, 2.61 [95% CI, 1.87-3.64]; P < .001) or those in the not recertified group (HR, 1.72 [95% CI, 1.25-2.37]; P < .001) had a significantly higher incidence of licensure loss than surgeons in the on-time recertification group. Surgeons in the lapsed recertification group did not differ significantly from those in the not recertified group (HR, 1.31 [95% CI, 0.87-1.97]; P = .20). The Figure shows the cumulative incidence for loss-of-license actions by recertification status.

Figure. Cumulative Incidence of Loss-of-License Actions by Recertification Status.

The on-time recertification group was the reference group for significance testing in the Cox proportional hazards model. Proportionality assumption was tested using R software and was met for individual covariates and the model. HR indicates hazard ratio. The tick marks on the curves represent each 1-year discrete interval.

aThe not recertified group includes 2452 surgeons at time 0, including 1045 surgeons with lapsed recertification who eventually recertified and 1407 who did not recertify. As those with lapsed certificates recertified, they moved to the lapsed recertification group (treating lapsed recertification as a time-dependent variable).

Discussion

General surgeons in the on-time recertification group had the lowest incidence of loss-of-license actions, whereas surgeons in the lapsed recertification or not recertified groups had higher incidences of loss of license. Whether maintaining certification and disciplinary actions are causally related cannot be determined from these data because other characteristics of surgeons might also explain the observed differences (eg, solo-practice status).6 Whether failure to maintain continuous board certification is an indicator of the likelihood that surgeons will receive a severe licensure action requires further study.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.Lipner RS, Hess BJ, Phillips RL Jr. Specialty board certification in the United States: issues and evidence. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2013;33(suppl 1):S20-S35. doi: 10.1002/chp.21203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teirstein PS. Boarded to death—why maintenance of certification is bad for doctors and patients. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(2):106-108. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1407422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gray BM, Vandergrift JL, Johnston MM, et al. Association between imposition of a maintenance of certification requirement and ambulatory care-sensitive hospitalizations and health care costs. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2348-2357. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.12716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayes J, Jackson JL, McNutt GM, Hertz BJ, Ryan JJ, Pawlikowski SA. Association between physician time-unlimited vs time-limited internal medicine board certification and ambulatory patient care quality. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2358-2363. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holmboe ES, Wang Y, Meehan TP, et al. Association between maintenance of certification examination scores and quality of care for Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(13):1396-1403. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.13.1396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xierali IM, Rinaldo JC, Green LA, et al. Family physician participation in maintenance of certification. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(3):203-210. doi: 10.1370/afm.1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]