Key Points

Question

What is the association between preoperative proteinuria and postoperative acute kidney injury and 30-day unplanned readmission among patients with and without known renal dysfunction at the time of surgery?

Findings

In this population-based study of 153 767 patients with and without known preoperative renal dysfunction, preoperative proteinuria was an indicator of probable postoperative acute kidney injury and 30-day unplanned readmission independent of preoperative renal dysfunction.

Meaning

Identification and early intervention of patients at risk for postoperative acute kidney injury through preoperative urinalysis assessments may improve patient outcomes.

Abstract

Importance

Proteinuria indicates renal dysfunction and is a risk factor for morbidity among medical patients, but less is understood among surgical populations. There is a paucity of studies investigating how preoperative proteinuria is associated with surgical outcomes, including postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI) and readmission.

Objective

To assess preoperative urine protein levels as a biomarker for adverse surgical outcomes.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A retrospective, population-based study was conducted in a cohort of patients with and without known preoperative renal dysfunction undergoing elective inpatient surgery performed at 119 Veterans Affairs facilities from October 1, 2007, to September 30, 2014. Data analysis was conducted from April 4 to December 1, 2016. Preoperative dialysis, septic, cardiac, ophthalmology, transplantation, and urologic cases were excluded.

Exposures

Preoperative proteinuria as assessed by urinalysis using the closest value within 6 months of surgery: negative (0 mg/dL), trace (15-29 mg/dL), 1+ (30-100 mg/dL), 2+ (101-300 mg/dL), 3+ (301-1000 mg/dL), and 4+ (>1000 mg/dL).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcome was postoperative predischarge AKI and 30-day postdischarge unplanned readmission. Secondary outcomes included any 30-day postoperative outcome.

Results

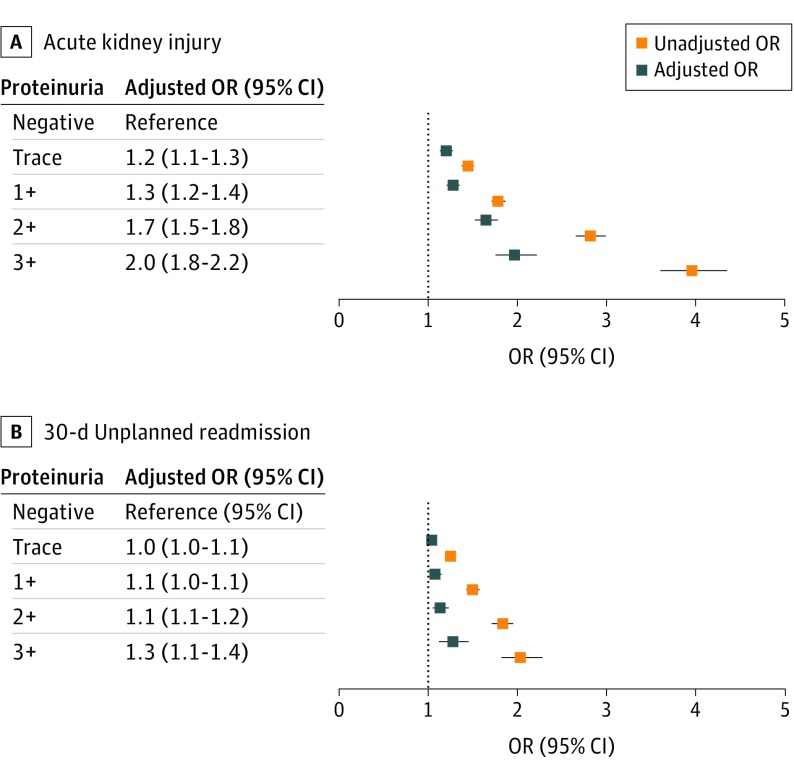

Of 346 676 surgeries, 153 767 met inclusion criteria, with the majority including orthopedic (37%), general (29%), and vascular procedures (14%). Evidence of proteinuria was shown in 43.8% of the population (trace: 20.6%, 1+: 16.0%, 2+: 5.5%, 3+: 1.6%) with 20.4%, 14.9%, 4.3%, and 0.9%, respectively, of the patients having a normal preoperative estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). In unadjusted analysis, preoperative proteinuria was significantly associated with postoperative AKI (negative: 8.6%, trace: 12%, 1+: 14.5%, 2+: 21.2%, 3+: 27.6%; P < .001) and readmission (9.3%, 11.3%, 13.3%, 15.8%, 17.5%, respectively, P < .001). After adjustment, preoperative proteinuria was associated with postoperative AKI in a dose-dependent relationship (trace: odds ratio [OR], 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1-1.3, to 3+: OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.8-2.2) and 30-day unplanned readmission (trace: OR, 1.0; 95% CI, 1.0-1.1, to 3+: OR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.1-1.4). Preoperative proteinuria was associated with AKI independent of eGFR.

Conclusions and Relevance

Proteinuria was associated with postoperative AKI and 30-day unplanned readmission independent of preoperative eGFR. Simple urine assessment for proteinuria may identify patients at higher risk of AKI and readmission to guide perioperative management.

This population-based study examines the outcomes of acute kidney injury and readmission in patients with preoperative proteinuria.

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is defined as functional injury or impairment relative to physiologic demand categorized into severity stages 1 to 3 associated with morbidity, mortality, and increased health care costs.1,2 Studies have shown that increasing AKI stage severity is associated with long-term mortality.3,4 Postoperative renal dysfunction and severity are associated with poor outcomes, including prolonged length of stay, 30- and 90-day mortality, and progression to end-stage renal disease within 1 year.4,5 The Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes task force identified preexisting renal insufficiency as the greatest risk for overall AKI and stressed early detection for potential prevention.1 Although predictors associated with postoperative AKI following noncardiac surgery have been identified,5,6,7 challenges remain to correctly and efficiently risk stratify patients. Preoperative renal insufficiency may be underreported because patients with diminished estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFR) without reported chronic kidney disease diagnoses experience poor outcomes, including surgical readmission.8

Renal function is traditionally measured using eGFR during preoperative risk assessment. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes suggests that new strategies are needed to better detect preoperative renal insufficiency to improve clinical outcomes, including the use of biomarkers to predict risk of AKI.1 Microalbuminuria, also known as proteinuria or urine protein, is a marker for renal dysfunction that can be measured using a random spot urinalysis or urine dipstick test.9,10 Traditionally, studies have used preoperative proteinuria assessments to predict postoperative outcomes in cardiac,11 urology,12 and transplant surgery13 given associations with cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality.14,15,16 However, there remains a paucity of studies investigating how preoperative proteinuria is associated with surgical outcomes apart from these subspecialties. We hypothesized that preoperative proteinuria is associated with the development of postoperative predischarge acute kidney injury and postdischarge 30-day unplanned readmission among patients with and without known renal dysfunction at the time of surgery.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study examining surgical outcomes among patients undergoing surgery performed at 119 Veterans Affairs facilities from October 1, 2007, through September 30, 2014. Data analysis was conducted from April 4 to December 1, 2016. Patients were considered eligible if they underwent elective, nonemergent surgery at a Veterans Affairs facility during the study period as defined by the Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Patients having inpatient surgery (length of stay ≥2 days) with evidence of at least 1 preoperative urinalysis result and both a preoperative and postoperative serum creatinine level result to assess AKI were selected. To evaluate postdischarge outcomes and reduce biases, patients were excluded from the analysis if they had evidence of preoperative dialysis or sepsis. Patients who died during the hospitalization were also excluded to assess patients at risk for readmission after discharge. In addition, patients experiencing cardiac, transplantation, and urology procedures had already been studied and were excluded given implicit pathophysiologic or related procedures (ie, cardiopulmonary bypass, renal transplantation, complete or partial nephrectomy) that may confound renal outcomes. Patients undergoing ophthalmology procedures were also excluded owing to small sample size. This study was reviewed and approved by the Veterans Affairs Central Institutional Review Board with a waiver of informed consent.

Data Sources and Variables

Data sources include the Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program 17 and the Veterans Affairs Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). Detailed surgical characteristics and outcomes for each surgical procedure were obtained from Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Additional demographic, pharmacy, laboratory, and postdischarge outcomes were obtained from administrative data from the Veterans Affairs electronic health care record stored within the CDW.

The main exposure of interest for this study was preoperative proteinuria as assessed by urinalysis results contained within the CDW laboratory data. Proteinuria was categorized as negative (0 mg/dL), trace (15-29 mg/dL), 1+ (30-100 mg/dL), 2+ (101-300 mg/dL), 3+ (301-1000 mg/dL), and 4+ (>1000 mg/dL). Preoperative urine microalbumin data were not included. For the purposes of this study, 3+ and 4+ levels were combined into one 3+ category. Only the chronologically closest laboratory results for eGFR, serum creatinine, and urine protein levels within 6 months prior to the surgery date of interest were included. Normal preoperative renal function was classified as a preoperative eGFR greater than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2.1 Chronic kidney disease was defined by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes (585.XX).

This cohort study assessed 2 main postoperative outcomes: postoperative predischarge AKI and 30-day postdischarge, unplanned readmission. Postoperative AKI was defined as a categorical variable according to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes work group, as any increase in postoperative serum creatinine of 0.3 mg/dL or more (to convert to micromoles per liter, multiply by 88.4) or a 50% increase from preoperative baseline serum creatinine level.1 Acute kidney injury severity was defined by stage for descriptive purposes as stage 1 (mild), 0.3 mg/dL or higher or a 50% increase in postoperative serum creatinine level from preoperative baseline; stage 2 (moderate), increase double from baseline; and stage 3 (severe), increase triple from baseline or increase from baseline serum creatinine level to 4.0 mg/dL or higher or initiation of renal replacement therapy.1 Unplanned readmissions were defined as inpatient admissions, excluding potentially planned procedures as identified by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services algorithm: bone marrow transplant, organ transplant, maintenance chemotherapy, rehabilitation, or a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services–identified potentially planned procedure.18 Potentially planned procedures were defined as unplanned if the primary diagnosis for admission was acute or related to a complication of care.18 Primary admission diagnosis codes were queried for all readmissions to further understand specific reasons for readmissions.

Additional outcomes included having any 30-day emergency department (ED) visit and renal recovery. Postdischarge ED visits within 30 days, like inpatient readmissions, were obtained from the CDW. Complete renal recovery at the time of discharge was defined as a postoperative serum creatinine level returned to less than 20% above baseline serum creatinine level or discharge serum creatinine level less than 2.0 mg/dL; partial renal recovery was defined as having a persistent increase in serum creatinine level more than 20% above baseline value without requiring renal replacement therapy/dialysis; no renal recovery was defined as a need for renal replacement therapy at the time of hospital discharge identified by ICD-9-CM diagnosis and procedure codes.19

Additional covariates gathered from the CDW included demographics (eg, race/ethnicity, sex, marital status), preoperative comorbidities, and operative characteristics collected by the Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program. All postoperative laboratory data were obtained for each patient and summarized as highest and lowest postoperative results during the hospitalization. Pharmacy data were obtained using CDW pharmacy domains. Preoperative medications were defined as active medications available the week prior to surgery according to outpatient medication documentation, with bowel preparation medications captured up to 45 days before surgery. Postoperative medications were limited to those given during inpatient administrations. Preoperative Veterans Affairs drug class coding identifiers were queried to account for any antibiotic, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, antihypertensive, diuretic, intravenous contrast, vasopressor, crystalloid or colloid, and total parenteral nutrition administered preadmission, preoperative inpatient, or postoperative until the time of discharge. Intraoperative medication administrations were not included in this study.

Statistical Analysis

Univariate and bivariate statistics were used to describe the overall population by the exposure, 5 levels of proteinuria, and each outcome of postoperative predischarge AKI and 30-day postdischarge readmission. χ2 Tests examined associations among categorical variables with differences among continuous variables evaluated using 2-sided t tests. Forward stepwise selection logistic regression was used to examine the association between each outcome and proteinuria as a categorical variable controlling for patient, procedure, and medication administration factors. Patients were then stratified into categories of normal or abnormal preoperative renal function, as defined by eGFR, and analyzed in similar fashion. Correlates of proteinuria (any vs none) were identified using logistic regression and Harrell ranking technique to identify and rank the relative contribution of variables to the model by calculating the difference between the χ2 for each variable and its degrees of freedom (χ2df).20 An α level of .05 identified statistically significant associations, and all analyses were completed with SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

The study cohort included 153 767 nonemergent surgeries from 134 765 patients in 119 Veterans Affairs facilities (eFigure in the Supplement). Of surgeries performed with a preoperative urinalysis result within 6 months available, levels of proteinuria were as follows: none, 86 631 (56.3%); trace, 31 738 (20.6%); 1+, 24 511 (16%); 2+, 8511 (5.5%); and 3+, 2376 (1.6%). The mean (SD) time prior to surgery from the most recent urinalysis was 30.9 (42.3) days (range, 0-180) and from serum creatinine level measurement was 9.3 (12.2) days (range, 0-129). The mean time from the most recent eGFR result was 13.2 (22.4) days (range, 0-180); only 10% of patients had their closest eGFR measured more than 29 days prior to surgery. Procedures involving patients missing a preoperative urinalysis (n = 114 486) were performed on healthier patients with less comorbidity than procedures included in our study (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Patient Characteristics

Patient characteristics were typical of a VA surgical population: mostly elderly white men with independent functional status, American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) class 3, and hypertension (eTable 1 in the Supplement). The most frequent surgical procedures were orthopedic (37.1%), general (28.8%), and vascular surgery (13.8%). Other specialty types included neurologic (8.1%), thoracic (6.6%), otolaryngology (2.3%), gynecology (1.4%), plastic (0.9%), podiatry (0.9%), and nonotolaryngologic oral surgery (0.2%). A total of 6920 (4.5%) surgeries were performed on 8592 patients with chronic kidney disease with a mean eGFR of 45.6 (19.5 mL/min/1.73 m2). Of 1329 (19.2%) surgeries performed on patients with chronic kidney disease, preoperative proteinuria prevalence increased monotonically over the 5 categories, with 2.5% of the patients having no proteinuria and up to 24.8% having 3+ proteinuria (P < .001).

The presence and level of proteinuria varied by patient characteristics and medical conditions, with higher preoperative urine protein levels among those patients of black race, partially or totally dependent functional status, prior ED visits or inpatient admissions within 6 months prior to surgery, ASA class 4, having a contaminated or infected wound classification, and a variety of medical conditions associated with impaired renal function (Table 1). Preoperative proteinuria was also associated with expected eGFR trends and elevated systolic blood pressure, as well as serum creatinine and serum urea nitrogen levels postoperatively (Table 2). Perioperative medication administrations are described in eTable 2 in the Supplement.

Table 1. Patient Demographics, Health Care Utilization, Preoperative Comorbidities, and Procedure Characteristics by Proteinuriaa.

| Characteristic | Procedures, No. (%) | Proteinuria, No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Trace | 1+ | 2+ | 3+ | ||

| Overall, No. | 153 767 | 86 571 | 31 676 | 24 603 | 8457 | 2460 |

| Surgical specialty, No. (%) | ||||||

| Orthopedic | 56 998 (37.1) | 35 850 (41.4) | 11 183 (35.3) | 7310 (29.8) | 2129 (25.0) | 526 (22.1) |

| General | 44 205 (28.8) | 21 554 (24.9) | 9756 (30.8) | 8917 (36.4) | 3147 (37.0) | 831 (35.0) |

| Peripheral vascular | 21 282 (13.8) | 10 935 (12.6) | 4206 (13.3) | 3815 (15.6) | 1728 (20.3) | 598 (25.2) |

| Neurosurgery | 12 534 (8.2) | 7822 (9.0) | 2642 (8.3) | 1524 (6.2) | 431 (5.1) | 115 (4.8) |

| Thoracic surgery | 10 089 (6.6) | 5831 (6.7) | 2096 (6.6) | 1505 (6.1) | 522 (6.1) | 135 (5.7) |

| Otolaryngology | 3504 (2.3) | 1895 (2.2) | 762 (2.4) | 572 (2.3) | 212 (2.5) | 63 (2.7) |

| Gynecology, plastic, podiatry, oral surgery | 5121 (3.3) | 2729 (3.2) | 1084 (3.4) | 864 (3.5) | 336 (4.0) | 108 (4.5) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 63.7 (11.3) | 62.9 (10.9) | 63.8 (11.7) | 65.2 (11.6) | 66.0 (10.9) | 64.9 (9.9) |

| Men | 143 288 (93.2) | 80 032 (92.4) | 29 563 (93.2) | 23 217 (94.7) | 8161 (95.9) | 2315 (97.4) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 118 761 (80.6) | 69 066 (83.5) | 23 647 (77.4) | 18 243 (77.4) | 6140 (74.8) | 1665 (72.3) |

| Black | 25 730 (17.5) | 12 035 (14.6) | 6323 (20.7) | 4896 (20.8) | 1897 (23.1) | 579 (25.1) |

| Other | 2850 (1.9) | 1612 (2.0) | 573 (1.9) | 439 (1.9) | 167 (2.0) | 59 (2.6) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 28.9 (14.6) | 29.1 (18.4) | 28.7 (6.8) | 28.4 (6.9) | 28.7 (7.1) | 29.0 (7.1) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 15 907 (10.4) | 8576 (9.9) | 3381 (10.7) | 2724 (11.1) | 977 (11.5) | 249 (10.5) |

| Married | 71 712 (46.7) | 41 799 (48.3) | 14 360 (45.3) | 10 912 (44.6) | 3654 (43.0) | 987 (41.5) |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 66 038 (43.0) | 36 190 (41.8) | 13 977 (44.1) | 10 855 (44.3) | 3876 (45.6) | 1140 (48.0) |

| Functional health status | ||||||

| Independent | 139 469 (90.7) | 81 402 (94.0) | 28 129 (88.7) | 20 854 (85.1) | 7101 (83.5) | 1983 (83.5) |

| Partially dependent | 12 155 (7.9) | 4616 (5.3) | 3022 (9.5) | 3036 (12.4) | 1139 (13.4) | 342 (14.4) |

| Totally dependent | 2103 (1.4) | 595 (0.7) | 579 (1.8) | 613 (2.5) | 267 (3.1) | 49 (2.1) |

| Health care utilization in 6 mo prior, mean (SD) | ||||||

| ED visits | 1.0 (1.9) | 0.8 (1.7) | 1.0 (2.1) | 1.3 (2.2) | 1.4 (2.3) | 1.5 (2.3) |

| Inpatient admissions | 0.9 (2.3) | 0.8 (2.1) | 1.1 (2.5) | 1.3 (2.6) | 1.4 (2.9) | 1.6 (2.8) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 6962 (4.5) | 2118 (2.5) | 1300 (4.1) | 1717 (7.0) | 1238 (14.6) | 589 (24.8) |

| ASA classification | ||||||

| 1-2 | 27 280 (17.7) | 18 892 (21.8) | 5028 (15.9) | 2698 (11.0) | 575 (6.8) | 87 (3.7) |

| 3 | 107 623 (70.0) | 59 449 (68.6) | 22 826 (72.0) | 17 507 (71.5) | 6114 (71.9) | 1727 (72.8) |

| 4-5 | 18 824 (12.2) | 8290 (9.6) | 3884 (12.2) | 4306 (17.5) | 1822 (21.4) | 562 (23.6) |

| Bleeding disorders | 9205 (6.0) | 4130 (4.8) | 2195 (6.9) | 1936 (7.9) | 736 (8.7) | 208 (8.8) |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| No or controlled by diet alone | 112 066 (72.9) | 67 833 (78.3) | 22 839 (72.0) | 15 986 (65.2) | 4473 (52.6) | 935 (39.4) |

| Oral agent dependent | 22 798 (14.8) | 11 608 (13.4) | 5020 (15.8) | 4172 (17.0) | 1556 (18.3) | 442 (18.6) |

| Insulin dependent | 18 903 (12.3) | 7190 (8.3) | 3879 (12.2) | 4353 (17.8) | 2482 (29.2) | 999 (42.1) |

| Dyspnea | ||||||

| No dyspnea | 132 889 (86.4) | 75 881 (87.6) | 27 295 (86.0) | 20 686 (84.4) | 7089 (83.3) | 1938 (81.6) |

| Minimal exertion | 19 318 (12.6) | 10 076 (11.6) | 4106 (12.9) | 3460 (14.1) | 1272 (15.0) | 404 (17.0) |

| At rest | 1558 (1.0) | 674 (0.8) | 336 (1.1) | 364 (1.5) | 150 (1.8) | 34 (1.4) |

| DNR status | 2406 (1.6) | 997 (1.2) | 517 (1.6) | 599 (2.4) | 233 (2.7) | 60 (2.5) |

| Alcohol use, >2 drinks/d (2 wk prior) | 12 440 (8.1) | 7287 (8.4) | 2435 (7.7) | 1950 (8.0) | 630 (7.4) | 138 (5.8) |

| Hemiplegia | 3862 (2.5) | 1740 (2.0) | 815 (2.6) | 847 (3.5) | 343 (4.0) | 117 (4.9) |

| Congestive heart failure | 1336 (0.9) | 444 (0.5) | 289 (0.9) | 342 (1.4) | 185 (2.2) | 76 (3.2) |

| History of transient ischemic attacks | 5845 (3.8) | 3072 (3.6) | 1228 (3.9) | 1009 (4.1) | 416 (4.9) | 120 (5.1) |

| Current smoker within 1 y | 51 385 (33.4) | 28 555 (33.0) | 10 664 (33.6) | 8424 (34.4) | 2864 (33.7) | 878 (37.0) |

| Corticosteroid use for chronic condition | 3822 (2.5) | 1880 (2.2) | 871 (2.7) | 773 (3.2) | 220 (2.6) | 78 (3.3) |

| Hypertension requiring medication | 108 289 (70.4) | 58 152 (67.1) | 22 900 (72.2) | 18 323 (74.8) | 6856 (80.6) | 2058 (86.6) |

| History of MI (6 mo prior) | 834 (0.5) | 319 (0.4) | 180 (0.6) | 206 (0.8) | 93 (1.1) | 36 (1.5) |

| Revascularization/amputation for PVD | 12 394 (8.1) | 5459 (6.3) | 2634 (8.3) | 2585 (10.6) | 1265 (14.9) | 451 (19.0) |

| Previous PTCA procedure | 14 117 (9.2) | 7365 (8.5) | 2965 (9.3) | 2490 (10.2) | 982 (11.5) | 315 (13.3) |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 14 386 (9.4) | 6896 (8.0) | 3103 (9.8) | 2767 (11.3) | 1240 (14.6) | 380 (16.0) |

Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); DNR, do not resuscitate; ED, emergency department; MI, myocardial infarction; PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; PVD, peripheral vascular disease.

All differences were significant at P < .001, determined with a χ2 test for categorical variables and a t test for continuous variables.

Table 2. Operative Characteristics and Postoperative Laboratory Dataa.

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedures | Proteinuria | |||||

| Negative | Trace | 1+ | 2+ | 3+ | ||

| Overall, No. | 153 767 | 86 571 | 31 676 | 24 603 | 8457 | 2460 |

| Work RVU, U | 20.1 (7.5) | 20.6 (7.2) | 19.9 (7.7) | 19.2 (8.0) | 18.6 (7.8) | 18.1 (7.9) |

| Total operation time, h | 2.7 (1.7) | 2.6 (1.6) | 2.6 (1.7) | 2.6 (1.7) | 2.5 (1.7) | 2.5 (1.7) |

| Length of postoperative surgical stay, d | 5.2 (4.0) | 5.0 (3.7) | 5.6 (4.2) | 6.0 (4.5) | 6.3 (4.7) | 6.2 (4.6) |

| Wound classification, No. (%) | ||||||

| Clean | 97 855 (63.6) | 59 639 (68.8) | 19 514 (61.5) | 13 190 (53.8) | 4289 (50.4) | 1223 (51.5) |

| Clean/contaminated | 41 338 (26.9) | 21 238 (24.5) | 9042 (28.5) | 7680 (31.3) | 2668 (31.4) | 710 (29.9) |

| Contaminated | 6833 (4.4) | 2793 (3.2) | 1477 (4.7) | 1698 (6.9) | 667 (7.8) | 198 (8.3) |

| Infected | 7729 (5.0) | 2959 (3.4) | 1703 (5.4) | 1937 (7.9) | 885 (10.4) | 245 (10.3) |

| Discharge destination, No. (%) | ||||||

| Community | 135 852 (88.4) | 77 623 (89.6) | 27 829 (87.7) | 21 222 (86.6) | 7189 (84.5) | 1989 (83.7) |

| Subacute care | 17 915 (11.7) | 9008 (10.4) | 3909 (12.3) | 3289 (13.4) | 1322 (15.5) | 387 (16.3) |

| Estimated intraoperative blood loss, mL | 337.4 (276.7) | 345.1 (259.5) | 340.0 (268.5) | 327.7 (283.7) | 322.3 (325.7) | 303.0 (266.0) |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate, mL/min/1.73 m2 | ||||||

| Highest | 79.3 (46.2) | 79.5 (46.3) | 81.1 (46.2) | 79.7 (46.2) | 74.1 (44.7) | 63.3 (42.3) |

| Lowest | 64.4 (39.2) | 65.4 (39.5) | 65.5 (39.2) | 63.1 (38.7) | 58.0 (37.2) | 49.4 (34.9) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | ||||||

| Highest | 151.7 (19.6) | 150.4 (18.9) | 152.5 (19.7) | 155.1 (20.3) | 161.0 (21.5) | 166.0 (22.4) |

| Lowest | 107.5 (14.8) | 106.7 (14.3) | 107.1 (14.9) | 107.8 (15.8) | 109.7 (16.7) | 113.1 (17.9) |

| White blood cell count, /μL | ||||||

| Highest | 11 600 (4500) | 8400 (3000) | 8200 (3200) | 8100 (3200) | 8200 (3000) | 8300 (3300) |

| Lowest | 8.3 (3.1) | 11.5 (4.2) | 11.7 (4.9) | 11.9 (5.0) | 12.0 (4.7) | 12.2 (6.0) |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | ||||||

| Highest | 1.1 (0.7) | 1.1 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.9) | 1.5 (1.0) | 1.9 (1.5) |

| Lowest | 0.9 (0.4) | 0.9 (0.4) | 0.9 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.7) | 1.4 (1.0) |

| Serum urea nitrogen, mg/dL | ||||||

| Highest | 17.5 (10.5) | 16.6 (9.1) | 17.9 (10.8) | 19.9 (12.9) | 24.4 (16.1) | 29.2 (18.3) |

| Lowest | 12.0 (6.9) | 11.5 (6.0) | 11.9 (7.0) | 13.0 (8.3) | 16.1 (11.1) | 20.0 (13.2) |

| Sodium, mEq/L | ||||||

| Highest | 138.4 (3.3) | 138.1 (3.2) | 138.5 (3.4) | 138.7 (3.6) | 139.1 (3.7) | 139.4 (3.8) |

| Lowest | 135.0 (3.4) | 134.9 (3.4) | 134.9 (3.4) | 134.9 (3.5) | 135.0 (3.6) | 135.1 (3.6) |

| Potassium, mEq/L | ||||||

| Highest | 3.7 (1.6) | 3.6 (1.6) | 3.8 (1.6) | 3.9 (1.5) | 4.0 (1.4) | 4.2 (1.4) |

| Lowest | 3.2 (1.4) | 3.2 (1.4) | 3.2 (1.4) | 3.3 (1.3) | 3.4 (1.2) | 3.5 (1.2) |

| International normalized ratio | ||||||

| Highest | 1.5 (0.8) | 1.5 (0.8) | 1.5 (0.8) | 1.5 (0.8) | 1.5 (0.8) | 1.5 (1.0) |

| Lowest | 1.1 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) |

Abbreviation: RVU, relative value unit.

SI conversion factors: To convert creatinine to millimoles per liter, multiply by 88.4; urea nitrogen to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.357; white blood cell count to ×109/L, multiply by 0.001; conversion of potassium and sodium to millimoles per liter is 1 to 1.

All differences were significant at P < .001, determined with a χ2 test for categorical variables and a t test for continuous variables.

Outcomes

Patients had a mean of 3.8 postoperative serum creatinine level readings during their postoperative stay (median, 3.0) and the mean time to peak postoperative creatinine level was 5.3 days (median, 2.0). Overall, 17 209 (11.2%) surgeries resulted in postoperative AKI prior to hospital discharge with the majority of patients (77.0%) having stage 1 injury (Table 3). Among AKI events, 15 477 (92.7%) patients achieved complete and 1139 (6.8%) achieved partial renal recovery, with 85 (0.5%) experiencing no renal recovery at the time of discharge. Complete renal recovery at the time of hospital discharge was achieved more often among patients without proteinuria and with less severe proteinuria (Table 3). Only 13.2% of patients in AKI stage 1 injury experienced no renal recovery compared with 16.7% in AKI stage 2 and 70.2% in AKI stage 3 (P < .01).

Table 3. In-Hospital Renal Outcomes and Postdischarge Outcomesa.

| Variable | Procedures, No. (%) | Proteinuria, % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Trace | 1+ | 2+ | 3+ | ||

| Overall, No. | 153 767 | 86 571 | 31 676 | 24 603 | 8457 | 2460 |

| In-hospital renal outcomes | ||||||

| AKI | 17 209 (11.2) | 7460 (8.6) | 3792 (12.0) | 3525 (14.4) | 1786 (21.0) | 646 (27.2) |

| Postoperative AKI stage | ||||||

| 1, mild | 13 250 (77.0) | 5318 (43.7) | 2585 (21.3) | 2461 (20.2) | 1303 (10.7) | 499 (4.1) |

| 2, moderate | 2620 (15.2) | 967 (47.5) | 967 (47.5) | 459 (22.6) | 379 (18.6) | 177 (8.7) |

| 3, severe | 1339 (7.8) | 496 (46.3) | 247 (23.1) | 228 (21.3) | 81 (7.6) | 19 (1.8) |

| Renal recoveryb | ||||||

| Complete | 15 477 (92.7) | 6345 (43.2) | 3221 (21.9) | 3016 (20.5) | 1538 (10.5) | 573 (3.9) |

| Partial | 1139 (6.8) | 375 (32.9) | 161 (14.1) | 309 (27.1) | 228 (20.0) | 67 (5.9) |

| None | 85 (0.5) | 27 (31.6) | 17 (19.5) | 20 (24.1) | 14 (16.4) | 7 (8.4) |

| Postdischarge outcomes | ||||||

| Any 30-d unplanned readmission | 16 665 (10.8) | 8067 (9.3) | 3587 (11.3) | 3258 (13.3) | 1343 (15.8) | 410 (17.3) |

| Any 30-d ED admission | 22 830 (14.8) | 12 213 (14.1) | 4739 (14.9) | 4023 (16.4) | 1415 (16.6) | 440 (18.5) |

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; ED, emergency department.

All differences were significant at P < .001, determined with a χ2 test for categorical variables and a t test for continuous variables.

Some data missing.

Regarding postdischarge outcomes, 16 665 (10.8%) surgeries resulted in an unplanned readmission and 22 830 (14.8%) in ED visits within 30 days after discharge. Readmission rates increased as preoperative proteinuria levels increased: 3+ proteinuria was associated with the highest readmission rate (17.3%) compared with 9.3% among patients with no proteinuria (P < .001). Postdischarge ED visits increased with increasing levels of preoperative proteinuria: 14.1% among patients with no proteinuria to 18.5% in those with 3+ proteinuria (P < .001). Patients with increasing proteinuria were also more likely to have any postoperative complication (negative, 8.9%; trace, 11.3%; 1+, 12.9%; 2+, 14.9%; and 3+, 15.4%; P < .01). Furthermore, patients who experienced postoperative AKI were more likely to have any complication compared with patients without postoperative AKI (22.3% vs 8.7%; P < .01). Patients with more severe AKI stages were associated with having any complication (stage 1, 2528 [19.1%], stage 2, 778 [29.7%], and stage 3, 581 [43.5%]; P < .01).

Multivariate Models of Postoperative AKI and Readmission

Models were adjusted for perioperative characteristics summarized in Tables 1 and 2 and eTable 2 in the Supplement. Preoperative proteinuria level was associated with postoperative predischarge AKI; trace proteinuria (odds ratio [OR], 1.4; 95% CI, 1.4-1.5; P < .001) up to 3+ (OR, 4.0; 95% CI, 3.6-4.4; P < .001) compared with no proteinuria. After adjustment, proteinuria remained independently associated with postoperative AKI in a dose-dependent fashion, with 3+ proteinuria having the highest association with AKI (OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.8-2.2; P < .001) (Figure 1). Model performance in predicting AKI improved when proteinuria was included with an improvement in R2 of 14.5% from 14.0% without proteinuria. Similarly, proteinuria was associated with 30-day unplanned readmission in both unadjusted and adjusted models in a dose-dependent association. Patients with 3+ proteinuria had the highest odds of readmission (OR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.1-1.4; P < .001) (Figure 1). Results were similar when patients missing a proteinuria assessment were included in the model with patients missing a proteinuria assessment having a slightly higher odds of both postoperative AKI (OR, 1.1; 95% CI, 1.1-1.1; P < .001) and readmission (OR, 1.0; 95% CI, 1.0-1.1; P = .001). After adjusting for preoperative proteinuria levels, odds of having any complication increased with AKI severity (stage 1: referent; stage 2: OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.6-1.9; stage 3: OR, 3.3; 95% CI, 3.0-3.6).

Figure 1. Unadjusted and Adjusted Odds Ratios (ORs) for Preoperative Proteinuria in Association With Acute Kidney Injury and 30-Day Unplanned Readmission.

A, Acute kidney injury. B, 30-Day unplanned readmission.

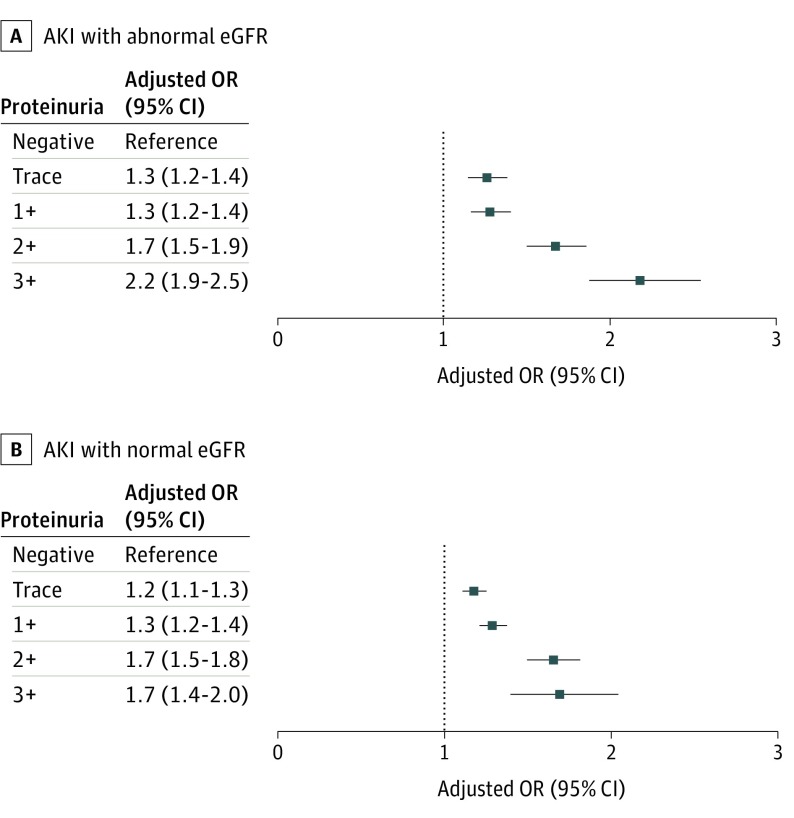

When stratified by preoperative renal insufficiency, patients with an abnormal eGFR (<60 mL/min/1.73 m2) were at increased odds of having AKI with or without proteinuria compared with patients with normal eGFR. Abnormal eGFR without proteinuria was independently associated with AKI (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.5-1.7; P < .001). The presence of proteinuria with an abnormal eGFR increased the odds of AKI in a dose-dependent relationship, with 3+ proteinuria having a 2.2-fold increase in odds of AKI (OR, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.9-2.5; P < .001) (Figure 2). Among patients with a normal eGFR at the time of surgery (eGFR>60 mL/min/1.73 m2), proteinuria was independently associated with increased odds of AKI in a dose-dependent association from trace (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1-1.3; P < .001) to 3+ proteinuria (OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.4-2.0; P < .001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Unadjusted and Adjusted Odds Ratios (ORs) of Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) by Preoperative Proteinuria Stratified by Preoperative Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR).

A, Abnormal eGFR. B, Normal eGFR.

Reasons for Readmission

Of 16 665 thirty-day postdischarge unplanned readmissions, common reasons for readmission overall were related to any wound (22.9%), mental health (22.2%), renal failure and electrolyte fluid disorder (22.1%), bleeding (19.7%), and gastrointestinal complication (14.8%) (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Preoperative proteinuria was associated with readmissions related to acute renal failure, anemia, cardiac arrhythmia, congestive heart failure exacerbation, peripheral vascular disease, urinary tract infection, and amputation-stump infection (P < .01).

Correlates of Preoperative Proteinuria

Many patient-level characteristics outlined in Tables 1 and 2 were associated with preoperative proteinuria. After adjustment, major correlates of having any preoperative proteinuria included diabetes (noninsulin dependent: OR 1.4; 95% CI, 1.35-1.44; insulin dependent: OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.9-2.0), black race (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.56-1.65), chronic kidney disease (OR, 2.2; 95% CI, 2.1-2.3), nonindependent functional status (partially dependent: OR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.57-1.71, totally dependent: OR 2.5; 95% CI, 2.22-2.72), and higher ASA class burden (class 3: OR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.3-1.7; class 4: OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.5-2.0; class 5: OR, 4.8; 95% CI, 2.4-9.9) (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Discussion

Our national study of a large veteran cohort found a dose-dependent association of preoperative proteinuria with adverse surgical outcomes, including postoperative predischarge AKI and 30-day postdischarge unplanned readmission. This association was present in patients with or without preoperative renal dysfunction. Proteinuria was associated with many patient characteristics; however, diabetes, black race, chronic kidney disease, dependent functional status, and higher ASA comorbidity burden were the most strongly correlated. Patients with preoperative proteinuria who were readmitted were more likely to experience medical complications that caused the readmission. Those without preoperative proteinuria who were readmitted were more likely to be readmitted for complications directly attributable to the surgery. Preoperative proteinuria as a biomarker can identify patients at higher risk of postoperative AKI and readmission, independent of baseline renal function as measured by eGFR.

Consistent with our study, preoperative renal insufficiency has been shown to be associated with adverse postoperative outcomes, including AKI and readmission.8,21 Mooney et al21 performed a meta-analysis of cardiac and vascular surgeries showing that preoperative renal insufficiency with an abnormal eGFR (<60 mL/min/1.73 m2) was associated with 30-day AKI and short- and long-term mortality. Preoperative renal insufficiency has been studied in a noncardiac, nontransplant surgery setting showing similar outcomes. Blitz and colleagues8 evaluated 39 989 patients with a heterogeneous case mix showing that preoperative renal insufficiency, measured by chronic kidney disease eGFR classifications, was associated with not only AKI, but also unplanned surgical readmissions. Our study supports these findings, suggesting that preoperative proteinuria is a predictor of postoperative AKI in a dose-dependent fashion independent of preoperative renal dysfunction. Model performance predicting AKI improved when preoperative proteinuria was included. Patients with normal preoperative renal function identified as having proteinuria were more likely to experience AKI than were patients with normal renal function without proteinuria.

Patients with diabetes, black race, chronic kidney disease, dependent functional status, and higher comorbidity burden should be screened for proteinuria with a urine dipstick urinalysis. However, with proteinuria having an estimated prevalence between 8% and 33% in the general population,22,23,24 preoperative urinalysis assessments for proteinuria may be beneficial among all surgical patients. Assessing preoperative urine dipstick analysis for proteinuria (96% sensitivity, 87% specificity10) regardless of baseline creatinine level or eGFR, may be a useful strategy for assessing the risk of postoperative AKI because proteinuria can manifest before changes in eGFR and serum creatinine level.

Because proteinuria is associated with renal dysfunction and cardiovascular disease, commonly mediated by hypertension and diabetes, it is not surprising that preoperative proteinuria was associated with readmissions related to reasons such as acute renal failure, anemia, cardiac arrhythmia, congestive heart failure exacerbation, peripheral vascular disease, and infection (eg, urinary tract infection). Understanding patients’ preoperative proteinuria status may prompt additional resource allocation and coordination at the time of discharge to mitigate readmissions for these specific reasons.

Renal literature indicates that most patients with less severe AKI experience full or complete recovery as seen in this study; however, AKI may not be transient, as studies have shown that AKI and its severity remain a predictor associated with progression to chronic kidney disease.19,25,26,27 We hypothesize that the paradox between preoperative proteinuria and AKI severity may be attributed to clinicians’ recognition of risk, avoidance of nephrotoxic medications, and aggressive intervention. Patients with normal preoperative renal function having as little as trace proteinuria developed postoperative AKI with partial to no renal recovery at the time of hospital discharge. These patients were also more likely to experience readmission than were patients without proteinuria. Although our study does not include long-term follow-up, patients with preoperative proteinuria may also be at risk of developing chronic kidney disease within 1 year of discharge according to a 2017 study by James et al.28 In that study, the investigators used the Alberta Kidney Disease Network database of 14 958 patients to understand predictors associated with chronic kidney disease among patients who experienced inpatient AKI. Patients who developed AKI having a baseline/prehospitalization eGFR greater than 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 with at least 2 outpatient serum creatinine measurements separated by at least 3 months between 30 days and 1 year after discharge were included. They found that renal recovery and preoperative proteinuria are predictors associated with developing chronic kidney disease within 1 year following discharge. Patients with increasing prehospitalization proteinuria, advanced age, higher stages of acute kidney injury, higher baseline/prehospitalization serum creatinine levels, and higher serum creatinine levels at discharge were significantly associated with developing chronic kidney disease in a dose-dependent fashion.

Identification and early intervention in patients at risk for AKI through preoperative urinalysis assessments may not only improve clinical outcomes, but also result in lower health care costs through fewer diagnostics tests, reduced lengths of stay, and potential mitigation of the risk of chronic kidney disease. Currently in the United States, patients undergoing elective surgery frequently receive preoperative evaluation with routine laboratory work consisting of a basic metabolic profile, a complete blood cell count, and coagulation assessment. Serum creatinine levels and eGFRs are provided within basic metabolic profiles in accordance with patient characteristics and normal reference ranges unique to calibration characteristics of the laboratory performing the analysis. Urine testing with a urinalysis is not the current standard of care and is selected on a clinician basis. Further investigations are warranted, including detailed cost-effectiveness analyses for preoperative urinalysis assessment.

Limitations

Our study found an association of preoperative proteinuria with adverse perioperative outcomes; however, it is not without limitations. The observational, retrospective design limits our ability to assign causation. Furthermore, the results of this study may be attributable to additional unmeasured residual confounders, despite rigorous controlling for available clinically and statistically significant confounders. Information was not available to understand granular detail surrounding the treatment for patients based on preoperative proteinuria or AKI severity. Modernized perioperative pathways, such as enhanced recovery after surgery, were not described within the Veterans Health Administration database used for this study and we assumed that patients were treated under traditional care pathways. Preoperative urine assessments are not routinely checked on all surgical patients, thereby contributing to selection bias of patients who had a urinalysis performed in the 6 months preceding surgery. Some preoperative proteinuria may reflect a transient process from conditions such as symptomatic congestive heart failure, dehydration, exercise, fever, or emotional stress not causing damage to the glomerular apparatus within the kidney.10 Furthermore, serum creatinine levels may vary by as much as 10% when assessed on a daily basis.1 Patients were included only if they survived until hospital discharge and therefore at risk for postdischarge readmission. Our study was unable to assess any associations between preoperative proteinuria and inpatient mortality. This study included a surgery demographic unique to a VA population and the results may not be generalizable to patient characteristics or specialties not represented.

Conclusions

Preoperative proteinuria was independently associated with postoperative AKI and 30-day postdischarge, unplanned readmission among patients with or without preoperative renal dysfunction. Preoperative proteinuria is a marker for perioperative AKI risk and readmission in this population. Identification and early intervention with patients at risk for AKI (eg, patients with diabetes, chronic kidney disease) through preoperative urinalysis assessments may improve patient outcomes by alerting care teams of excess risk despite normal eGFR. Future prospective studies are warranted to further understand how preoperative proteinuria affects perioperative outcomes.

eFigure. Study Population

eTable 1. Characteristics of Patients Missing Procedure Urinalysis Results compared to Analyzed Procedures

eTable 2. Perioperative Medication Administrations Associated with Preoperative Proteinuria and Outcomes

eTable 3. Readmission Reason by Preoperative Proteinuria

eTable 4. Correlates of Preoperative Proteinuria Ranked by Importance

References

- 1.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Group. Acute Kidney Injury (AKI). https://kdigo.org/guidelines/acute-kidney-injury/. Accessed February 15, 2017.

- 2.Goren O, Matot I. Perioperative acute kidney injury. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115(suppl 2):-. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bihorac A, Yavas S, Subbiah S, et al. . Long-term risk of mortality and acute kidney injury during hospitalization after major surgery. Ann Surg. 2009;249(5):851-858. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181a40a0b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korenkevych D, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, Thottakkara P, et al. . The pattern of longitudinal change in serum creatinine and 90-day mortality after major surgery. Ann Surg. 2016;263(6):1219-1227. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grams ME, Sang Y, Coresh J, et al. . Acute kidney injury after major surgery: a retrospective analysis of Veterans Health Administration data. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67(6):872-880. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.07.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kheterpal S, Tremper KK, Englesbe MJ, et al. . Predictors of postoperative acute renal failure after noncardiac surgery in patients with previously normal renal function. Anesthesiology. 2007;107(6):892-902. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000290588.29668.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kheterpal S, Tremper KK, Heung M, et al. . Development and validation of an acute kidney injury risk index for patients undergoing general surgery: results from a national data set. Anesthesiology. 2009;110(3):505-515. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181979440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blitz JD, Shoham MH, Fang Y, et al. . Preoperative renal insufficiency: underreporting and association with readmission and major postoperative morbidity in an academic medical center. Anesth Analg. 2016;123(6):1500-1515. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lameire N, Adam A, Becker CR, et al. ; CIN Consensus Working Panel . Baseline renal function screening. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(6A):21K-26K. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simerville JA, Maxted WC, Pahira JJ. Urinalysis: a comprehensive review. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71(6):1153-1162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang TM, Wu VC, Young GH, et al. ; National Taiwan University Hospital Study Group of Acute Renal Failure . Preoperative proteinuria predicts adverse renal outcomes after coronary artery bypass grafting. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(1):156-163. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010050553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bezinque A, Noyes SL, Kirmiz S, et al. . Prevalence of proteinuria and other abnormalities in urinalysis performed in the urology clinic. Urology. 2017;103:34-38. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2017.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan HC, Chen YJ, Lin JP, et al. . Proteinuria can predict prognosis after liver transplantation. BMC Surg. 2016;16(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s12893-016-0176-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hillege HL, Fidler V, Diercks GF, et al. ; Prevention of Renal and Vascular End Stage Disease (PREVEND) Study Group . Urinary albumin excretion predicts cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality in general population. Circulation. 2002;106(14):1777-1782. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000031732.78052.81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garg JP, Bakris GL. Microalbuminuria: marker of vascular dysfunction, risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Vasc Med. 2002;7(1):35-43. doi: 10.1191/1358863x02vm412ra [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klausen K, Borch-Johnsen K, Feldt-Rasmussen B, et al. . Very low levels of microalbuminuria are associated with increased risk of coronary heart disease and death independently of renal function, hypertension, and diabetes. Circulation. 2004;110(1):32-35. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133312.96477.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khuri SF, Daley J, Henderson W, et al. ; National VA Surgical Quality Improvement Program . The Department of Veterans Affairs’ NSQIP: the first national, validated, outcome-based, risk-adjusted, and peer-controlled program for the measurement and enhancement of the quality of surgical care. Ann Surg. 1998;228(4):491-507. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199810000-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horwitz LI, Partovian C, Lin Z, et al. . Development and use of an administrative claims measure for profiling hospital-wide performance on 30-day unplanned readmission. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(10)(suppl):S66-S75. doi: 10.7326/M13-3000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macedo E, Bouchard J, Mehta RL. Renal recovery following acute kidney injury. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2008;14(6):660-665. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e328317ee6e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrell FE., Jr Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis. New York, NY: Springer; 2001. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-3462-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mooney JF, Ranasinghe I, Chow CK, et al. . Preoperative estimates of glomerular filtration rate as predictors of outcome after surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(4):809-824. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318287b72c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim D, Lee DY, Cho SH, et al. . Diagnostic accuracy of urine dipstick for proteinuria in older outpatients. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2014;33(4):199-203. doi: 10.1016/j.krcp.2014.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomonaga Y, Risch L, Szucs TD, Ambühl PM. The prevalence of chronic kidney disease in a primary care setting: a Swiss cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e67848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White SL, Yu R, Craig JC, Polkinghorne KR, Atkins RC, Chadban SJ. Diagnostic accuracy of urine dipsticks for detection of albuminuria in the general community. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(1):19-28. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chawla LS, Amdur RL, Amodeo S, Kimmel PL, Palant CE. The severity of acute kidney injury predicts progression to chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2011;79(12):1361-1369. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chawla LS, Kimmel PL. Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease: an integrated clinical syndrome. Kidney Int. 2012;82(5):516-524. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chawla LS, Eggers PW, Star RA, Kimmel PL. Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease as interconnected syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(1):58-66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1214243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.James MT, Pannu N, Hemmelgarn BR, et al. . Derivation and external validation of prediction models for advanced chronic kidney disease following acute kidney injury. JAMA. 2017;318(18):1787-1797. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.16326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Study Population

eTable 1. Characteristics of Patients Missing Procedure Urinalysis Results compared to Analyzed Procedures

eTable 2. Perioperative Medication Administrations Associated with Preoperative Proteinuria and Outcomes

eTable 3. Readmission Reason by Preoperative Proteinuria

eTable 4. Correlates of Preoperative Proteinuria Ranked by Importance