Abstract

Background

This is a synopsis of the registry report from the Australia and New Zealand islet and pancreas transplant registry. The full report is available at http://anziptr.org/reports/.

Methods

We report data for all solid organ pancreas transplant activity from inception in 1984 to end 2017. Islet-cell transplantation activity is reported elsewhere. Data analysis was performed using Stata software version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

From 1984 to 2017 a total of 809 solid organ pancreas transplants have been performed in Australia and New Zealand, in 790 individuals. In 2017, 52 people received a pancreas transplant. By center, this was; Auckland (4), Monash (17), and Westmead (31). In 2017, 51 transplants were simultaneous pancreas kidney, whereas 1 was pancreas after kidney, and none were pancreas transplant alone.

Conclusions

The number of pancreas transplants performed in Australia and New Zealand was slightly lower in 2017 but continues to increase over time.

WAITING LIST

Overview of Waiting List Activity

Definitions

Patients join the waiting list on the date they are referred to the transplanting center; however, this may occur some time before their kidneys fail. Patients are therefore classified as “under consideration” until they medically require a kidney pancreas transplant. Once they require a kidney pancreas transplant they are classified as “active” on the list while they remain medically fit. The “under consideration” classification also captures people recently referred to the transplant center, who are still undergoing assessment about their medical fitness for pancreas transplant. People are referred to a transplanting center when they are already on dialysis and become “active” on the list as soon as they are accepted as medically fit. People referred to a transplanting center when their kidneys still function, become active once their kidney disease progresses to such a level that dialysis is planned in the near future. Once active on the waiting list, patients are transplanted in order of their waiting time, by blood group.

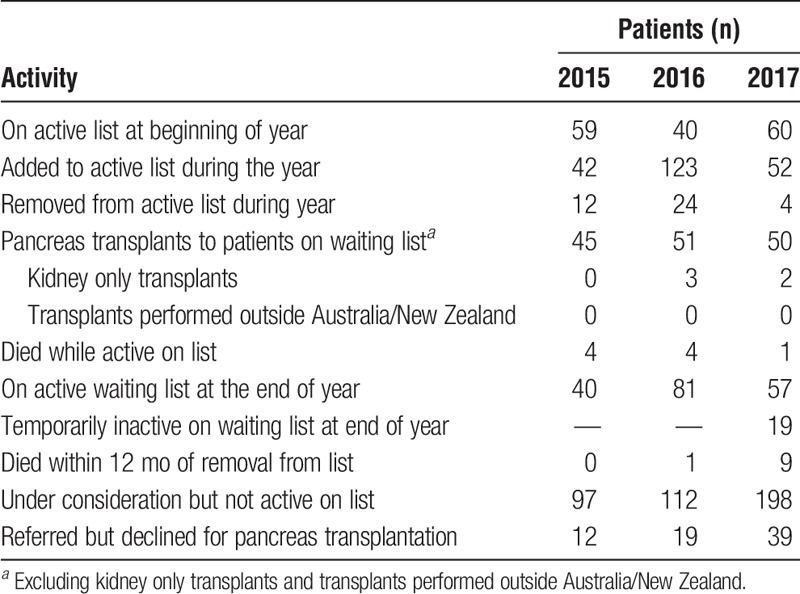

Patient Waiting List Flow

The patient waiting list activity in the last 3 years for Australia (Westmead and Monash Units) and New Zealand are shown in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. In Australia, although the number of transplants has increased over the last 3 years, the number of patients on the active waiting list has continued to increase.

TABLE 1.

Waiting list activity in Australia for the last 3 years

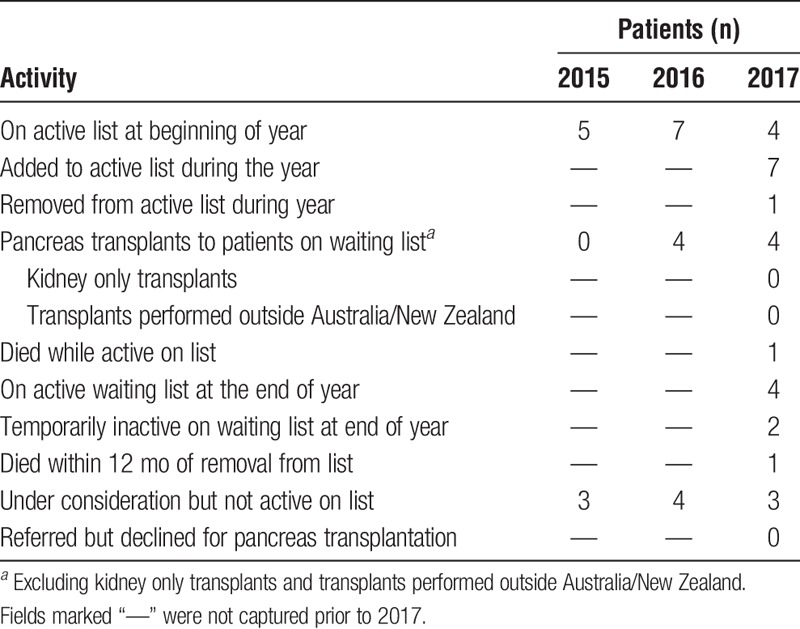

TABLE 2.

Waiting list activity in New Zealand for the last 3 years

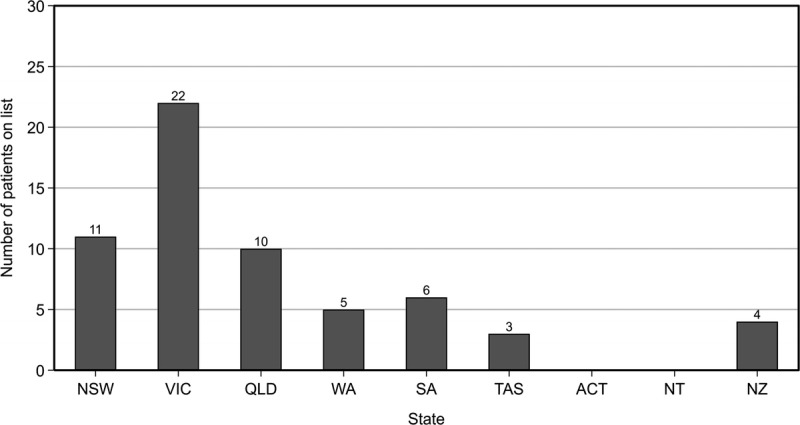

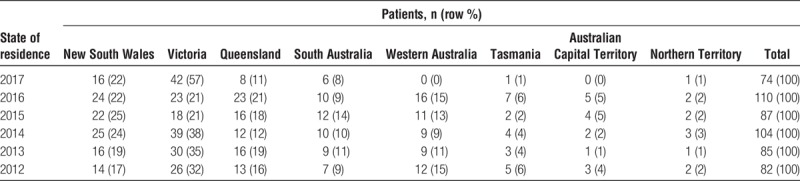

Distribution of Active Patients by State

Figure 1 and Table 3 show the state of residence for people active on the pancreas waiting list, by the pancreas transplanting center they were referred to (Australia only). For New Zealand data, there is no breakdown beyond that seen in Table 2.

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of people active on the waiting list by state/territory of residence as of December 2017.

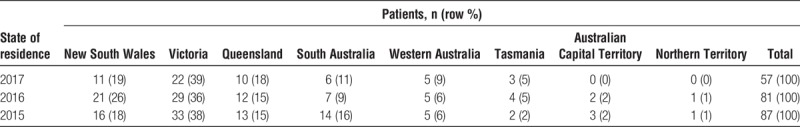

TABLE 3.

Patient state of residence for people active on the list, December 2017

New Referrals Received Over Time

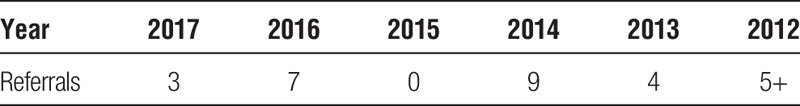

Tables 4 and 5 show the distribution of new referrals received by the transplanting units over time.

TABLE 4.

New referrals received by Westmead and Monash national pancreas units (Australia)

TABLE 5.

New referrals received by Auckland national pancreas transplant unit (New Zealand)

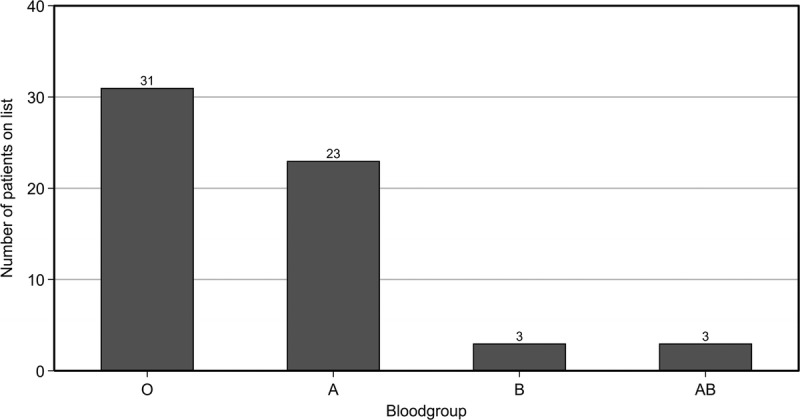

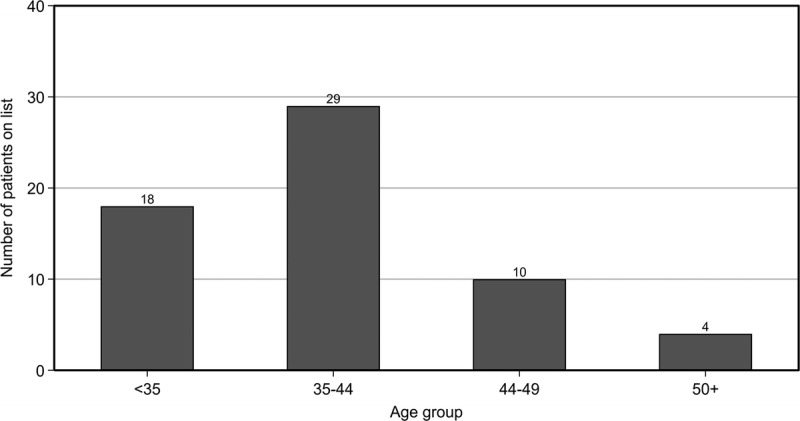

Patient Characteristics for Those Active on the List in 2016

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the distribution of other characteristics of those active on the waiting list in 2017, including the distribution of blood groups and patient ages.

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of people active on the list by their blood group as of December 2017.

FIGURE 3.

Distribution of people active on the list by their age as of December 2017.

PANCREAS TRANSPLANT RECIPIENTS

Pancreas Transplant Incidence

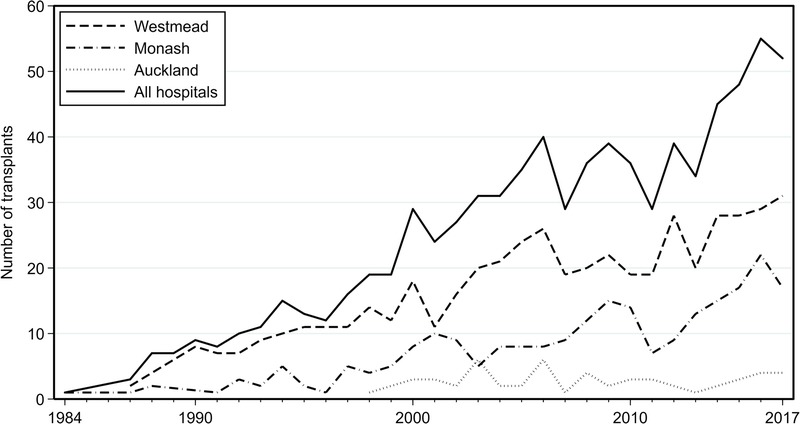

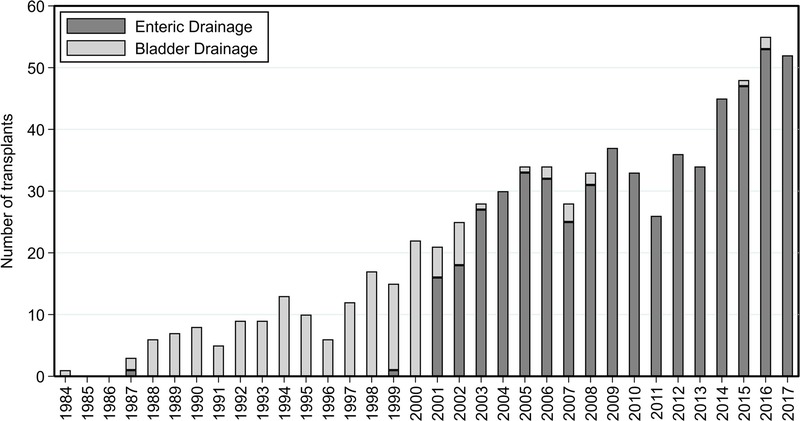

A total of 809 solid organ pancreas transplants have been performed in Australia and New Zealand (ANZ) from 1984-2017. Transplants have been performed in Westmead (511), Monash (238), Auckland (56), Royal Prince Alfred (1), Royal Melbourne Hospital (1), Queen Elizabeth Hospital (1), and Prince Henry (1). Figure 4 shows pancreas transplants over time. The number of transplants has substantially increased in the last decade compared with previous years.

FIGURE 4.

Incidence of pancreas transplants over time (1984 to 2017).

In 2017, 52 people received a pancreas transplant, by center this was; Auckland (4); Monash (17); Westmead (31). The number of transplants in 2017 increased by 5% compared to 2016.

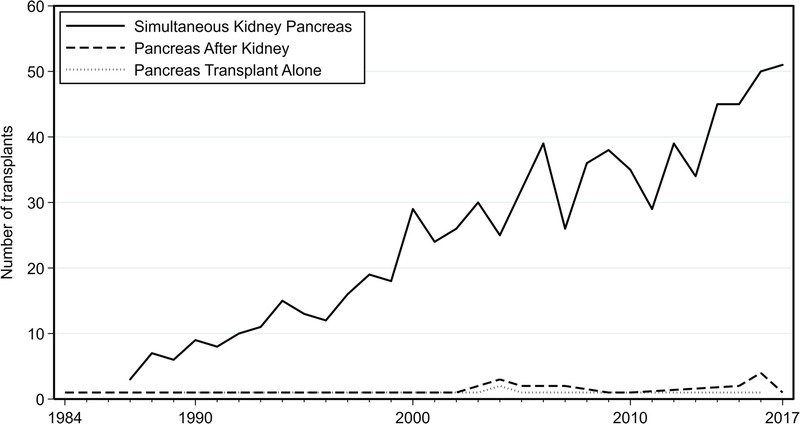

Not all pancreas transplant operations are undertaken with the same organs. Simultaneous pancreas-kidney (SPK) transplant is the most common operation, representing 99% of all pancreas transplants in Australia and New Zealand. From 52 transplants performed in 2017, 51 were SPK, 1 was pancreas after kidney (PAK), and none were pancreas transplant alone (PTA).

Pancreas after kidney operations are done for type 1 diabetic people who either had a first kidney transplant without a pancreas (most commonly from a living donor relative) and subsequently opt for a pancreas, or for people who underwent an SPK and have good kidney transplant function, but had a pancreas transplant failure, so need a further pancreas transplant. Pancreas transplant alone is a less common operation and occurs very rarely. On rarer occasions, a multiorgan transplant is undertaken which includes a pancreas transplant. There was 1 simultaneous pancreas, liver plus kidney transplant which was performed in 2005, 1 liver, pancreas plus intestine transplant in 2012, and 1 liver plus pancreas transplant in 2016. The distribution of operation types is shown in Figure 5, and the number of transplants by operation type is shown in Table 6.

FIGURE 5.

Pancreas transplants by type over time, Australia and New Zealand.

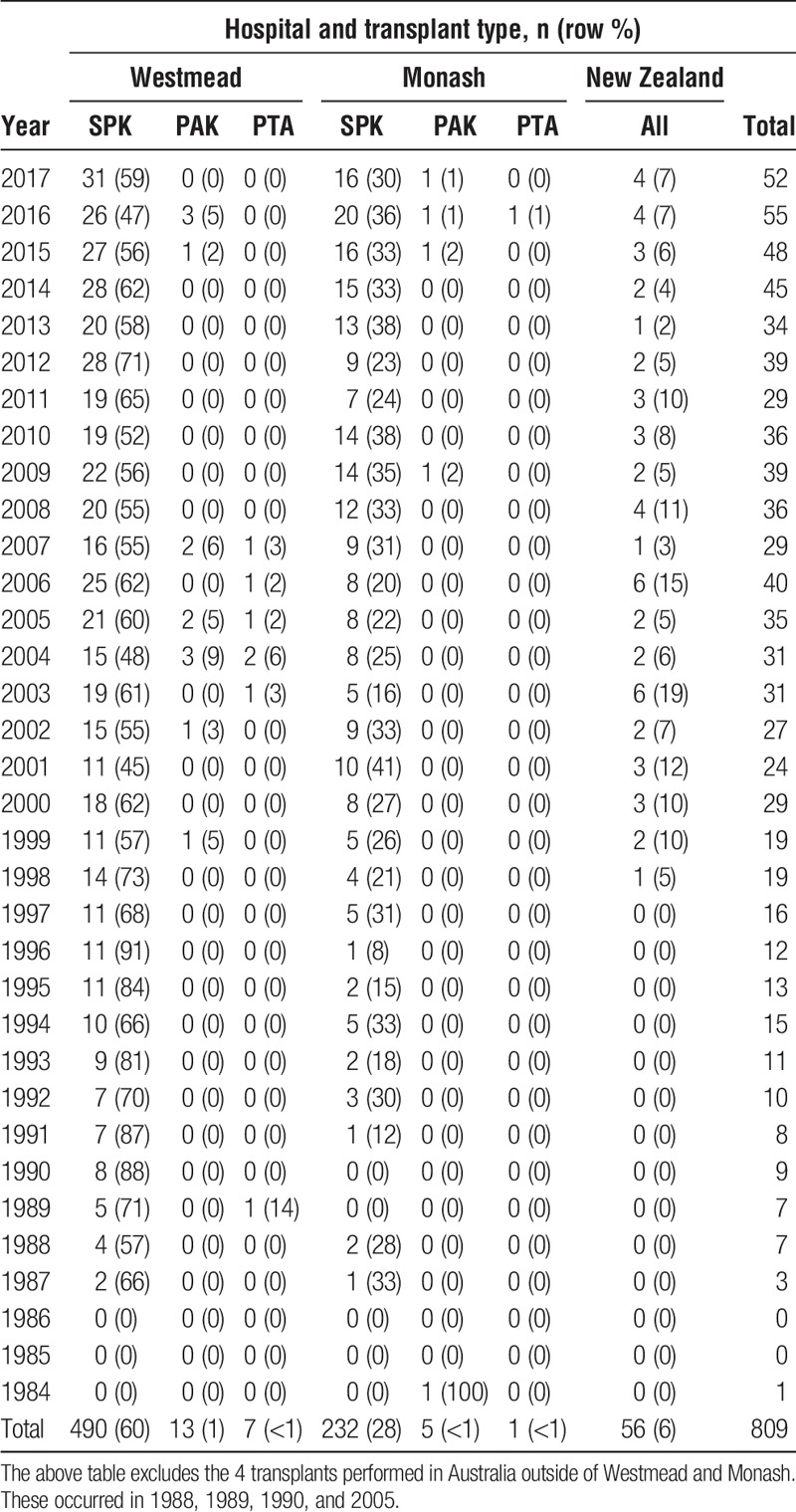

TABLE 6.

Pancreas transplant operations by center, over time

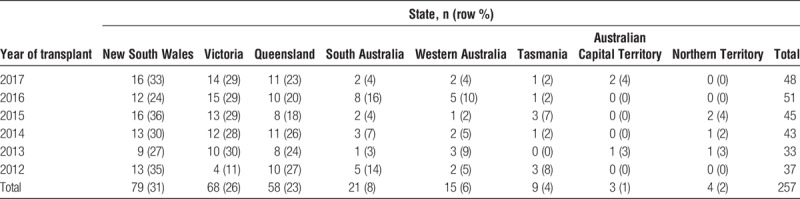

Patients Transplanted by State

The states of origin of the people receiving pancreas transplants are shown in Table 7. Numbers for New Zealand can be found in Table 6.

TABLE 7.

Distribution of state of residence of people receiving pancreas transplants in Australia over time

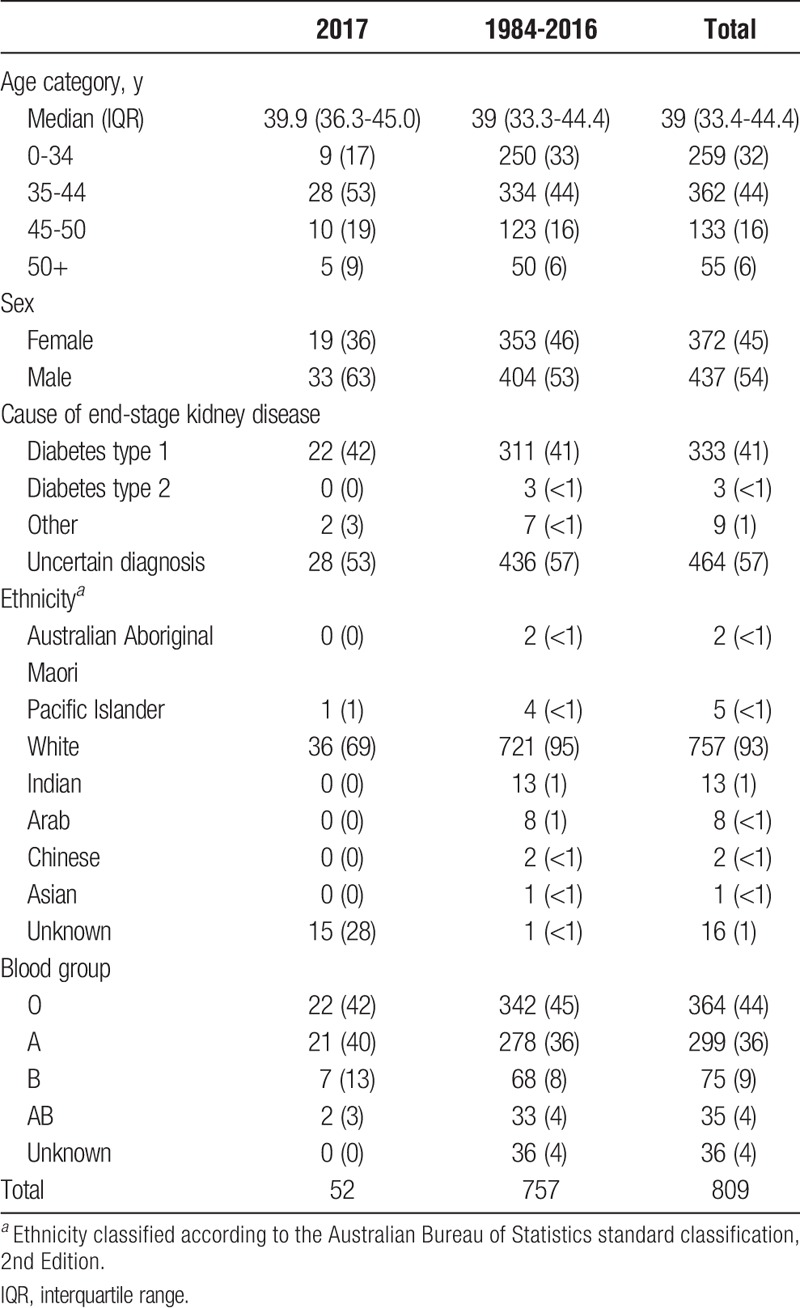

Demographics of New Pancreas Transplant Recipients

The characteristics of pancreas transplant recipients in 2017 and in previous years are shown in Table 8. The primary diagnosis causing end stage kidney disease of recipients during 2017 and historically was type I diabetes. The number of diabetic recipients with other cause of end stage kidney failure was small. The number of type II diabetics accepted for pancreas transplantation was also small, and none were transplanted in 2017.

TABLE 8.

Demographics and characteristics of pancreas transplant recipients

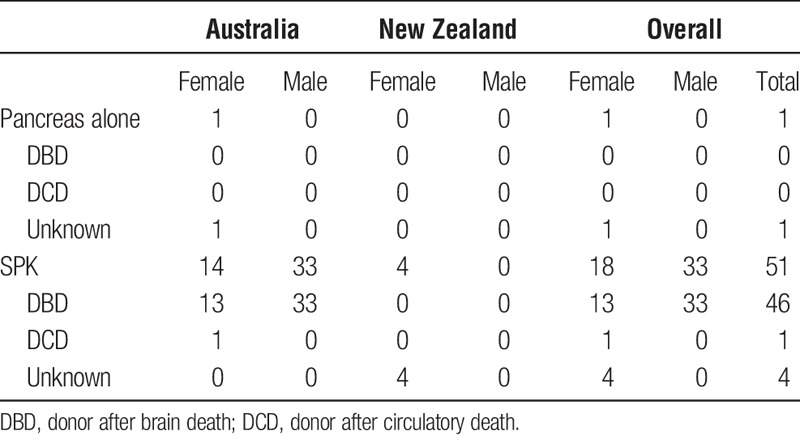

The type of pancreas transplants and the types of donors for transplants performed in 2017 is presented in Table 9, stratified by country and sex.

TABLE 9.

Cross-tabulation of pancreas transplant type and donor type by recipient country and sex

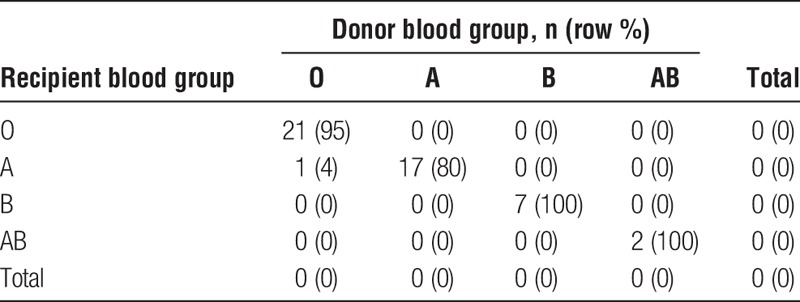

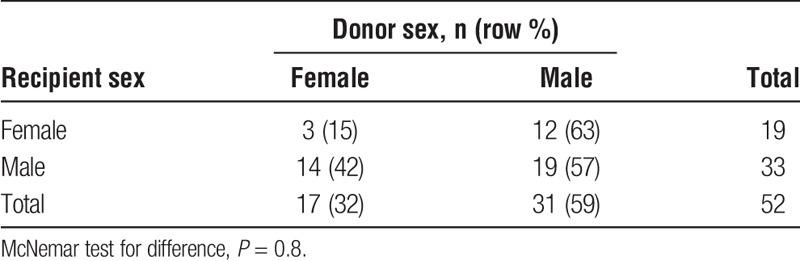

Balance of Donor and Recipient Characteristics in 2016

Cross tabulations of donor and recipient blood group and gender for people transplanted in 2017 are displayed in Table 10 and Table 11. These distributions remain similar to previous years.

TABLE 10.

Cross-tabulation of recipient and donor blood groups for 2016

TABLE 11.

Cross-tabulation of recipient and donor sex for 2016

Patient Survival

Patient survival is calculated from the date of transplantation until death. Patients still alive at the end of the follow-up period are censored. For people who had more than 1 transplant, their survival is calculated from the date of their first transplant. For these analyses, we had survival data for 790 patients, 19 of whom have received a second pancreas transplant, for a total of 809 pancreas transplants. Note that for the following survival plots survival proportion on the y-axes does not always start at zero; this is to better demonstrate some observed differences.

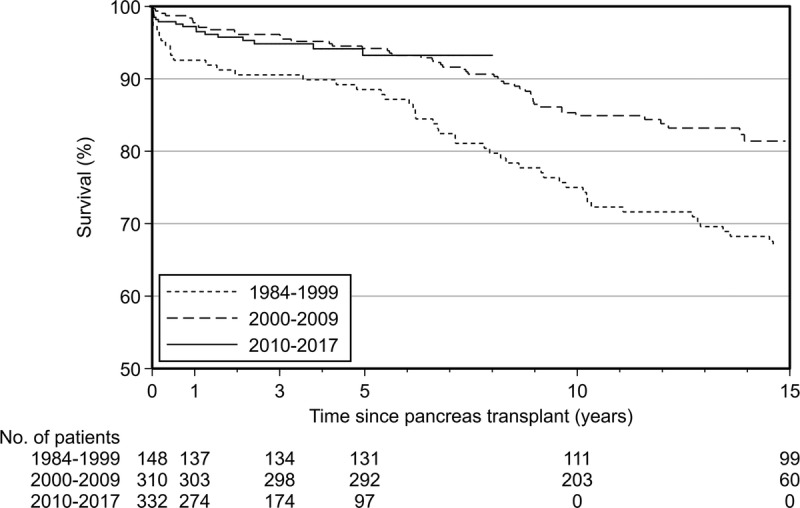

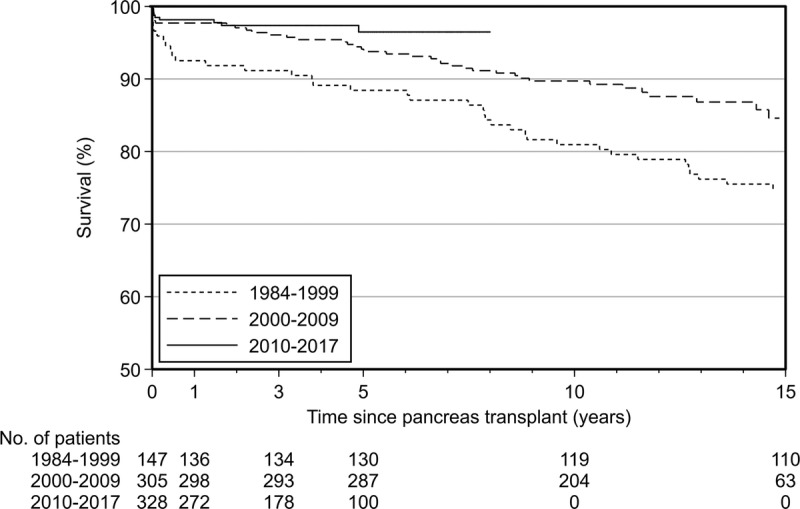

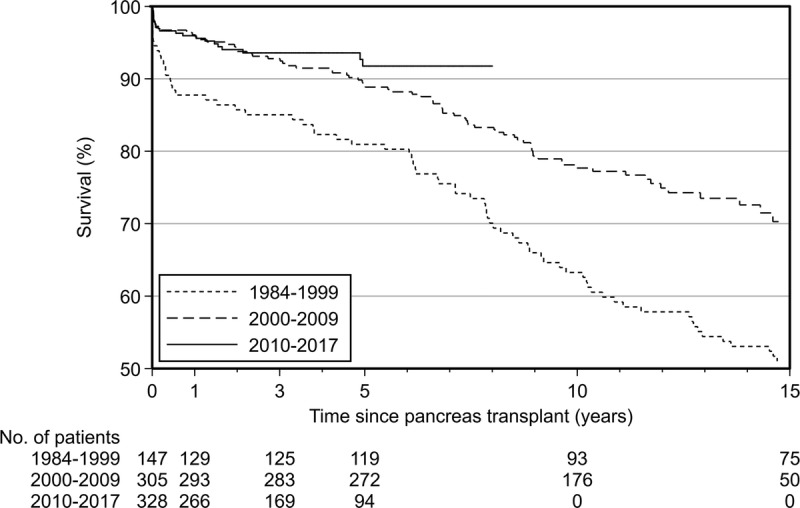

Patient survival by era of transplantation is shown in Figure 6. Survival has improved over time (P = 0.002). Survival at 1 year for people transplanted before 2000 was 92.6%; in recent years this has risen to 97.2%. Survival at 5 years was 88.5% for those transplanted before 2000, whereas for those transplanted in 2010 or later, 5-year survival was 93.2%.

FIGURE 6.

Patient survival by era of transplantation.

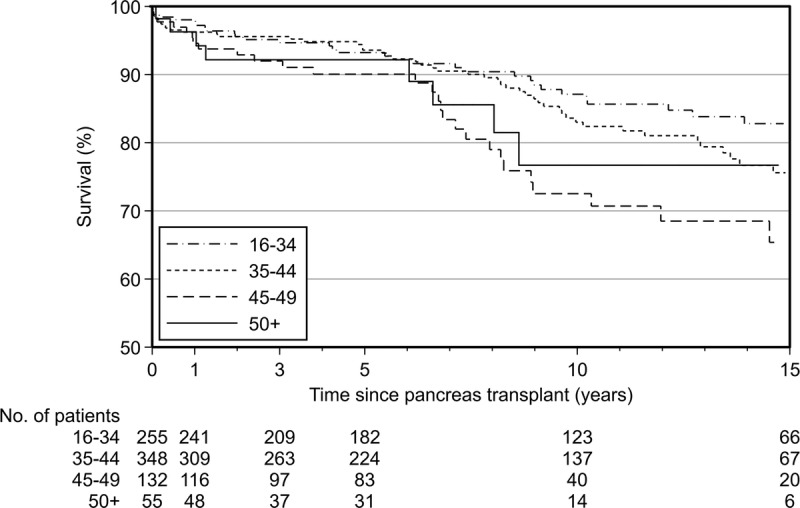

Patient survival by age at transplantation is shown in Figure 7. People that were older at the time of pancreas transplantation had poorer survival than those who were younger (P = 0.005). Survival at 1 year for recipients younger than 35 years was 98.0%, and for those aged 35 to 44 years was 96.2%, whereas for those aged 45 to 49 years was 94.6% and for those 50 or older was 96.3%. Five-year survival for those younger than 35 years was 93.3%, and for those aged 35 to 44 years was 93.6%, whereas for those aged 45 to 49 years was 90.1% and for those 50 years or older was 92.2%. The greater survival for the 50 years and older group suggests these recipients may be a more highly selected population.

FIGURE 7.

Patient survival by age at transplantation.

Pancreas Survival

Pancreas transplant survival was calculated from the time of transplant until the time of pancreas failure (defined as permanent return to insulin therapy or pancreatectomy). We calculated both pancreas failure including death with a functioning pancreas and pancreas failure censored for death with a functioning graft. For pancreas graft survival, we included all pancreas transplants undertaken, including those who had received a pancreas transplant twice (19 patients). At the time of this report, we had survival records for 809 pancreas transplants.

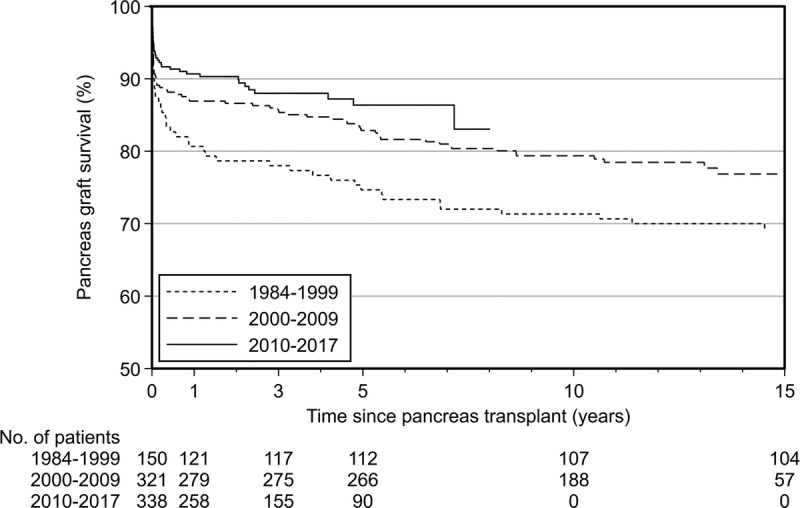

Survival of pancreas transplants has changed over time, as shown in Figure 8. Survival improved markedly over time (P = 0.02). For those transplanted prior to 2000, 1-year pancreas survival was 80.7%, and 5-year survival 74.7%. For those transplanted in 2010 or later, 1-year survival was 90.7% and 5-year survival 86.4%.

FIGURE 8.

Pancreas transplant survival over time (censored for death).

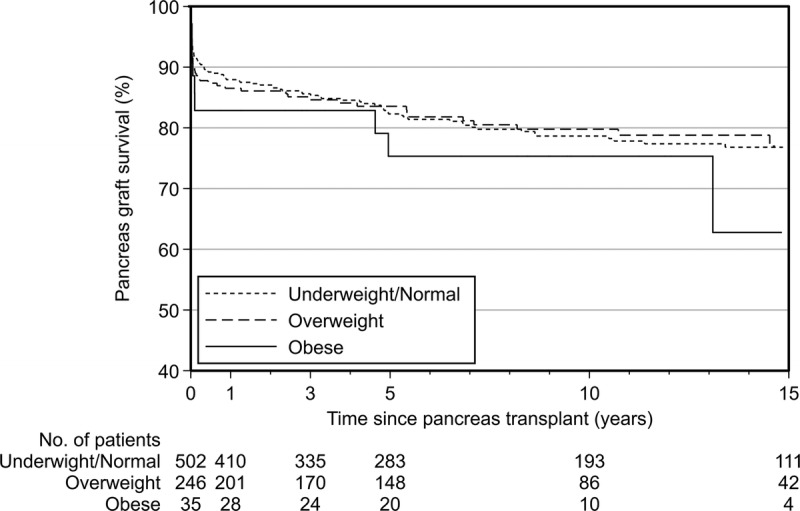

Pancreas survival by donor body mass index (BMI) is presented in Figure 9. Most donors (64%) were either underweight or normal (BMI <25). However, 31% were overweight (BMI 25-29) and 4% were obese (BMI 30+). Although Figure 9 suggests separation of survival curves, there was no statistical association between donor BMI and pancreas survival (P = 0.7). One-year pancreas survival was 87.9% for transplants where the donor was underweight/normal BMI, 86.5% for transplants where the donor was overweight, and 82.9% where the donor was obese.

FIGURE 9.

Pancreas survival censored for death with pancreas function, by donor BMI.

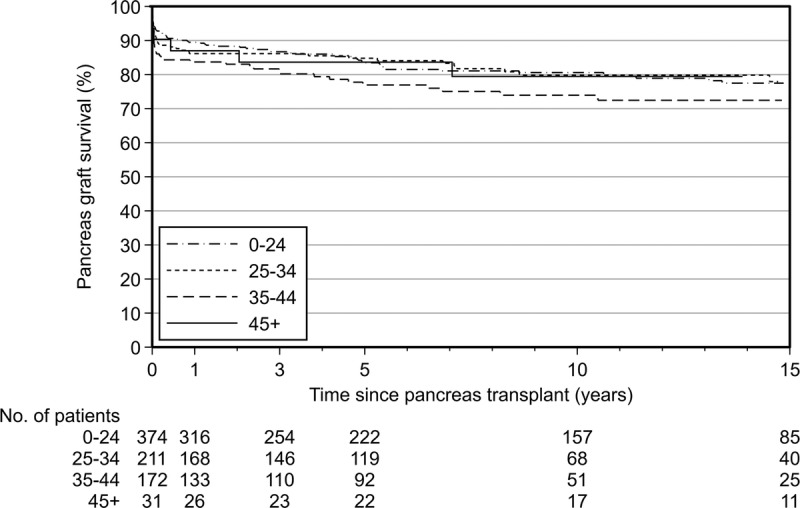

Pancreas survival by donor age is presented in Figure 10. The survival curves appear poorer for donors aged 35 to 44 years compared with those 45 and older, or younger donors, but this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.5). We can only hypothesize that any difference may be due to donors older than 45 years being a more highly selected group, compared to the donors aged 35 to 44 years. One-year pancreas survival was 89.5% for transplants from donors aged 0 to 24 years, 86.1% for donors aged 25 to 34 years, 83.7% for donors aged 35 to 44 years, and 87.0% for donors 45 years or older.

FIGURE 10.

Pancreas transplant survival, censored for death with function, by donor age.

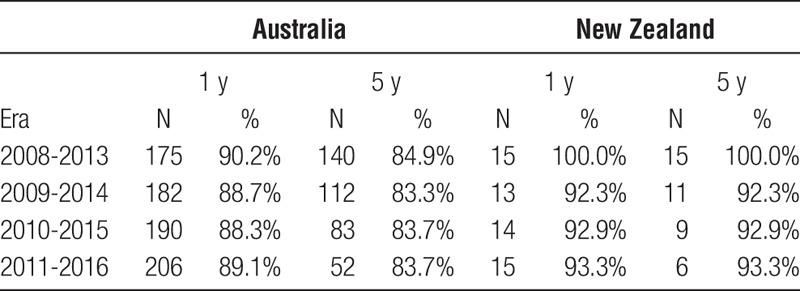

Pancreas graft survival at 1 and 5 years posttransplant, censored at death, and stratified by country and era of transplantation is presented in Table 12.

TABLE 12.

Pancreas graft survival at 1 and 5 years post transplant, censored at death, and stratified by country and era of transplantation

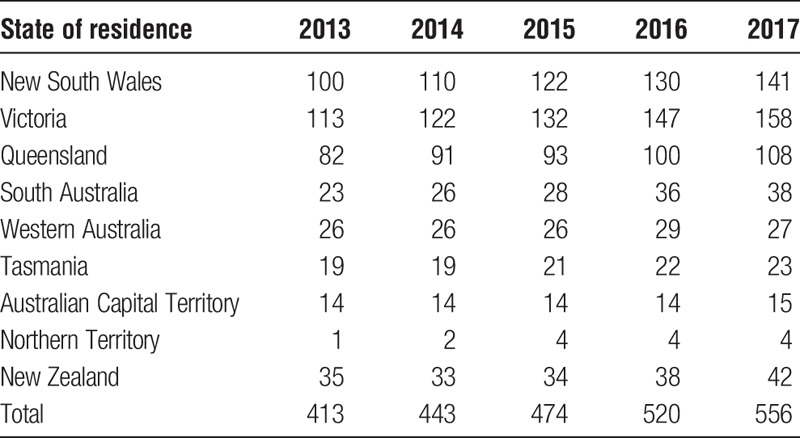

Prevalence of Functioning Pancreas Transplants

We calculated the point prevalence of people living in Australia and New Zealand who were alive with a functioning transplant on December 31, each year for the last 5 years (Table 13). The below numbers exclude people still alive, but whose pancreas transplant has failed. The number of functioning transplants is continuing to increase over time, as a consequence of the growing number of transplants, and their improved survival.

TABLE 13.

People alive with a functioning pancreas transplant in Australia and New Zealand by year and residence, at year's end

Kidney Transplant Survival

Kidney transplant survival was calculated for those who received SPK transplants, from the time of transplantation until the time of return to dialysis. We calculated both kidney failure including death with a functioning kidney and kidney failure censored for death with a functioning graft. For kidney graft survival, we included only SPK transplants and excluded PAK transplant recipients. We had survival records for 780 SPK transplant recipients.

Kidney survival improved over time, with longer survival for those transplanted in more recent years (P = 0.002). For those transplanted in 2000 or before, kidney transplant survival was 92.5% at 1 year and 88.4% at 5 years but was 98.2% at 1 year and 96.5% at 5 years for those transplanted in 2010 or later (Figure 11).

FIGURE 11.

Kidney transplant survival, censored for death, for SPK recipients over time.

The era effect was even stronger when considering kidney failure including death with kidney function (P < 0.001). For those transplanted before 2000, survival was 87.8% at 1 year and 81.0% at 5 years, but was 96.0% at 1 year and 91.8% at 5 years for those transplanted in 2010 or later (Figure 12).

FIGURE 12.

Kidney transplant survival, including death with a functioning kidney, for SPK recipients over time.

Pancreas Transplant Operative Data

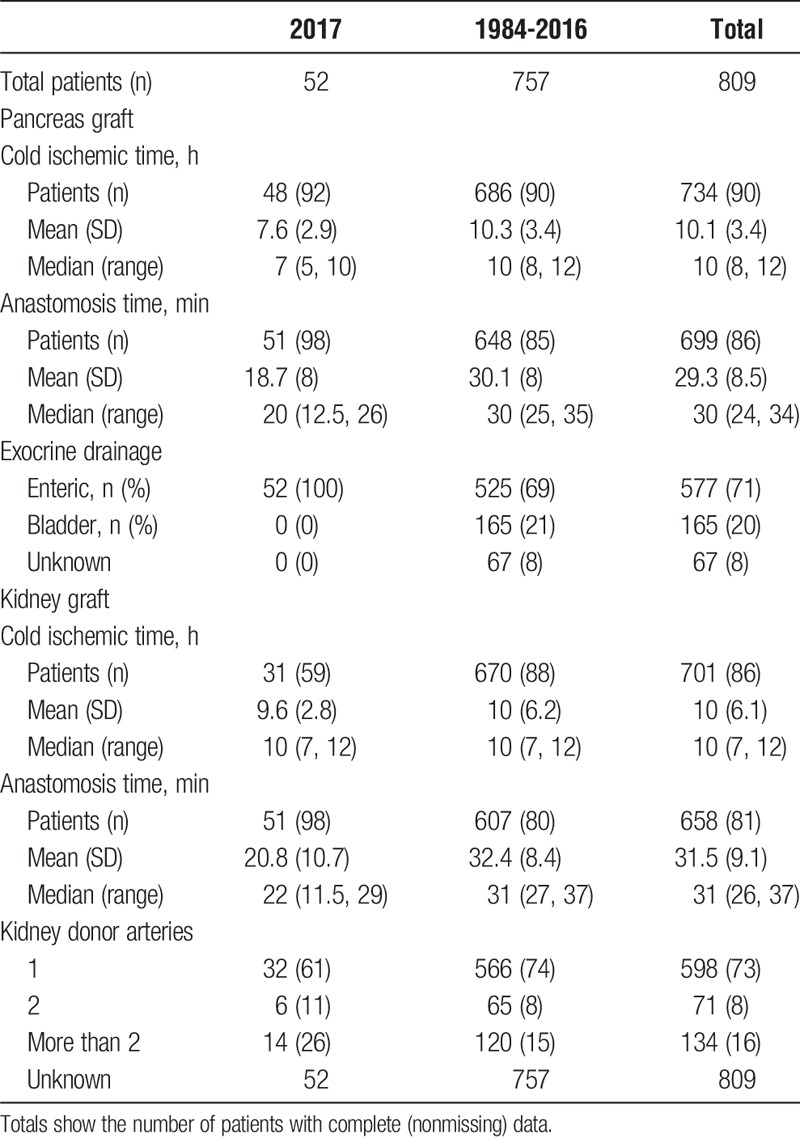

Characteristics of the pancreas transplant operations for 2017, previous years, and overall are shown in Table 14.

TABLE 14.

Descriptive characteristics of pancreas transplant operations

Surgical Technique

Exocrine drainage of the pancreas graft has changed over time. Enteric Drainage of the pancreas was first used in Australia and New Zealand during 2001. Figure 13 illustrates the number of transplants by pancreas duct management. Since 2001, most pancreas transplants have used enteric drainage of the pancreas duct.

FIGURE 13.

Change in management of exocrine drainage of the pancreas over time.

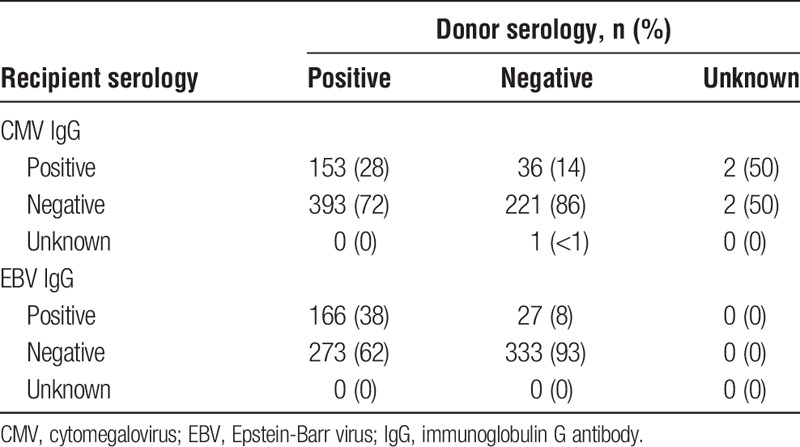

The cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) matching of donor-recipient pairs is shown in Table 15.

TABLE 15.

Infectious disease serology cross-tabulation of donor recipient pairs

PANCREAS DONORS

This section gives an overview of donors in 2017 and over time. Donor eligibility criteria guidelines are available in the TSANZ consensus statement,http://www.tsanz.com.au/organallocationprotocols/1 but briefly require donors to be over 25 kg, and up to the age of 45 years, without known diabetes mellitus or pancreatic trauma, or history of alcoholism or pancreatic trauma. Donation after circulatory death may be considered up to the age of 35 years. As these are guidelines, there may be occasions when there is minor deviation from these advised criteria.

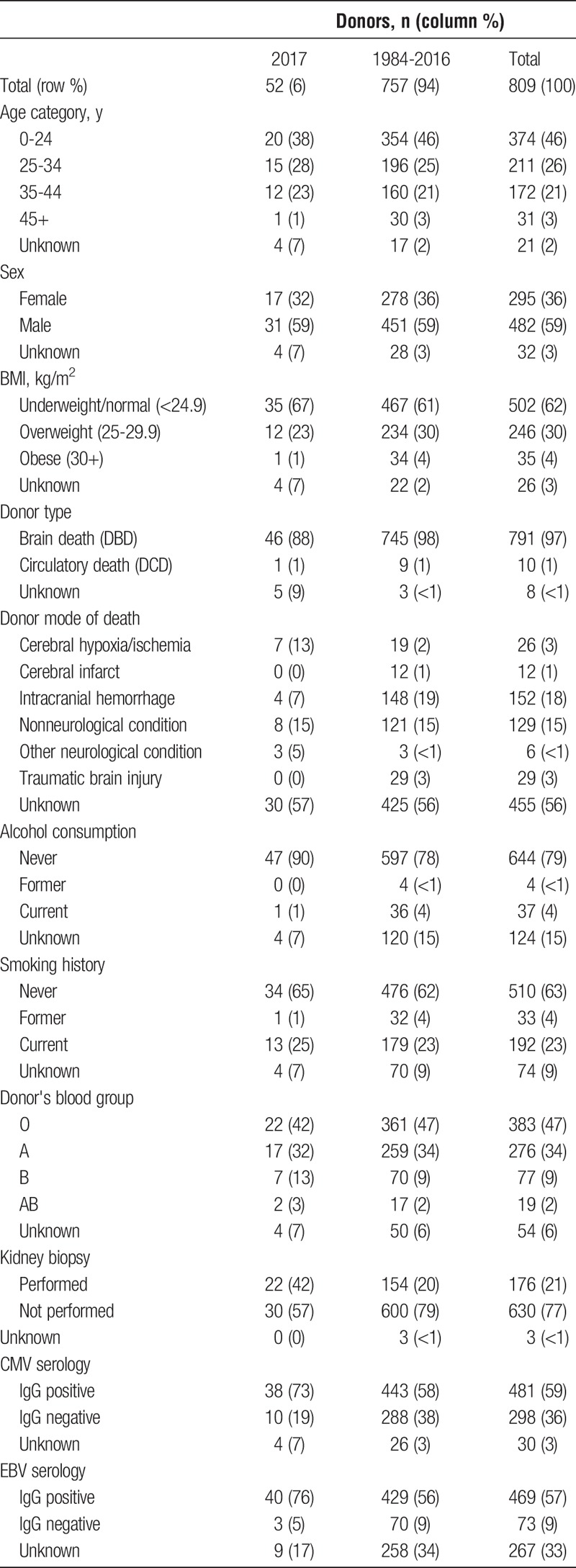

Donor BMI is perceived as impacting recipient outcomes. Obese donors are more likely to have fatty pancreas, which results in more difficult surgery and increased postoperative complications, and suboptimal insulin secretion. Alcohol consumption is defined by a history of consumption of more than 40 g/d. Table 16 describes pancreas donor characteristics in Australia and New Zealand to date.

TABLE 16.

Demographics and characteristics of pancreas transplant donors

Pancreas Donor Characteristics

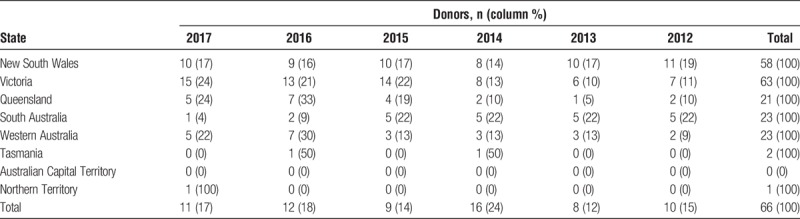

The distribution of donor states of origin is shown in Table 17.

TABLE 17.

Distribution of state of residence of pancreas donors in Australia over time

Donor and Recipient State/Territory

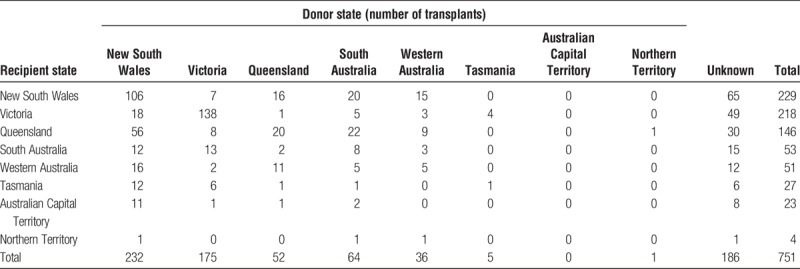

Table 18 shows the distribution of donor organs according to state of origin, cross-tabulated with the state of origin of the recipients who received those organs, for 2017, and from inception of the pancreas program. Note that these tables include Australian donors and recipients only.

TABLE 18.

Number of pancreas transplants by donor and recipient state of residence in Australia, all years

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of all Australia and New Zealand pancreas transplant collaborators; Prof Stephen Munn, Prof Peter Kerr, Prof John Kanellis, Mr Alan Saunder, Mr Roger Bell, Mr Ming Yii, Miss Nancy Suh, Mr Stephen Thwaites, Mr Michael Wu, Ms Tia Mark, Prof Philip O’Connell, Prof Jeremy Chapman, Dr Brian Nankivell, A/Prof Germaine Wong, Dr Natasha Rogers, Dr Brendan Ryan, Dr Lawrence Yuen, Prof Richard Allen, Ms Kathy Kable, Prof Wayne Hawthorne, Mr Abhijit Patekar.

Footnotes

Published online 6 September, 2018.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The registry is funded in part by a grant from the Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing.

The operation of this registry is legally mandated by the Australian Organ and Tissue Authority (OTA), hence institutional review board approval was not required.

A.C.W. is the registry executive officer. J.H. participated in the data analyst. P.R. is the transplant coordinator. W.R.M. is the data interpreter and article editor. H.L.P. is the data interpreter and article editor. H.P. is the data interpreter and article editor. P.J.K. is the biostatistics consultant.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: on behalf of Australia and New Zealand Pancreas Transplant collaborators

REFERENCE

- 1.(TSANZ) TTSoAaNZ. Clinical guidelines for organ transplantation from deceased donors. http://www.tsanz.com.au/organallocationprotocols/. Published 2017. Accessed June 4, 2018. [Google Scholar]