Key Points

Question

What is the effect of a one-time, group-administered behavioral treatment on urinary incontinence in older women?

Findings

In this multisite randomized clinical trial among 463 women 55 years or older, group-administered behavioral treatment showed statistically significant but clinically modest improvements at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months compared with control for urinary incontinence and all secondary outcomes except pelvic floor muscle strength. The incremental cost to achieve a treatment success was $723 at 3 months; group-administered behavioral treatment dominated at 12 months.

Meaning

Group-administered behavioral treatment may be a promising first approach to enhancing access to noninvasive behavioral treatment for women with urinary incontinence.

This multisite randomized clinical trial compares the effectiveness, cost, and cost-effectiveness of group-administered behavioral treatment vs no treatment for urinary incontinence in older women.

Abstract

Importance

Urinary incontinence (UI) guidelines recommend behavioral interventions as first-line treatment using individualized approaches. A one-time, group-administered behavioral treatment (GBT) could enhance access to behavioral treatment.

Objective

To compare the effectiveness, cost, and cost-effectiveness of GBT with no treatment for UI in older women.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Multisite randomized clinical trial (the Group Learning Achieves Decreased Incidents of Lower Urinary Symptoms [GLADIOLUS] study), conducted from July 7, 2014, to December 31, 2016. The setting was outpatient practices at 3 academic medical centers. Community-dwelling women 55 years or older with UI were recruited by mail and screened for eligibility, including a score of 3 or higher on the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Short Form (ICIQ-SF), symptoms of at least 3 months’ duration, and absence of medical conditions or treatments that could affect continence status. Of 2171 mail respondents, 1125 were invited for clinical screening; 463 were eligible and randomized; 398 completed the 12-month study.

Interventions

The GBT group received a one-time 2-hour bladder health class, supported by written materials and an audio CD.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Outcomes were measured at in-person visits (at 3 and 12 months) and by mail or telephone (at 6 and 9 months). The primary outcome was the change in the ICIQ-SF score. Secondary outcome measures assessed UI severity, quality of life, perceptions of improvement, pelvic floor muscle strength, and costs. Evaluators were masked to group assignment.

Results

Participants (232 in the GBT group and 231 in the control group) were aged 55 to 91 years (mean [SD] age, 64 [7] years), and 46.2% (214 of 463) were African American. In intent-to-treat analyses, the ICIQ-SF scores for GBT were consistently lower than control across all time points but did not achieve the projected 3-point difference. At 3 months, the difference in differences was 0.96 points (95% CI, −1.51 to −0.41 points), which was statistically significant but clinically modest. The mean (SE) treatment effects at 6, 9, and 12 months were 1.36 (0.32), 2.13 (0.33), and 1.77 (0.31), respectively. Significant group differences were found at all time points in favor of GBT on all secondary outcomes except pelvic floor muscle strength. The incremental cost to achieve a treatment success was $723 at 3 months; GBT dominated at 12 months.

Conclusions and Relevance

The GLADIOLUS study shows that a novel one-time GBT program is modestly effective and cost-effective for reducing UI frequency, severity, and bother and improving quality of life. Group-administered behavioral treatment is a promising first-line approach to enhancing access to noninvasive behavioral treatment for older women with UI.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02001714

Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI) is a prevalent condition that diminishes quality of life among older women at tremendous social and economic cost.1,2 Although there are several options available for treating UI, behavioral interventions are recommended by most evidence-based guidelines as first-line approach for treating urgency, stress, and mixed UI.3 Behavioral treatments can be delivered individually or in groups. Although individualized behavioral treatment programs have been studied extensively, demonstrating safety and effectiveness in patients with UI,1 these programs are sometimes met with resistance because they usually require multiple in-person visits and specialized health care professionals to teach and maintain the techniques.

For decades, pelvic floor muscle (PFM) training has been integrated into education and fitness classes to promote pelvic health during pregnancy and the postpartum period and to prevent future symptoms.4,5,6 Group modalities have also been used to deliver PFM training as a treatment for symptomatic women using general fitness programs or specific pelvic fitness classes.7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 Most of these programs focus on building PFM strength and involve multiple sessions across weeks or months. Less common are programs that take a broader behavioral approach, teaching women about bladder function, toileting techniques, bladder training, or behavioral strategies for bladder control, as well as programs that convey these skills in a classroom setting rather than in an exercise class.17,18,19,20,21,22

Although research on such bladder health classes is limited, early work shows that they can be effective for preventing UI in older women18,19,20 and demonstrates encouraging results for decreasing UI symptoms and micturition frequency.21,22 The objective of the Group Learning Achieves Decreased Incidents of Lower Urinary Symptoms (GLADIOLUS) study (trial protocol in Supplement 1), conducted from July 7, 2014, to December 31, 2016, was to evaluate the effectiveness, cost, and cost-effectiveness of a single 2-hour bladder health class to deliver an evidence-based behavioral treatment program supplemented with materials to guide home practice for older women with urgency, stress, or mixed UI. We hypothesized that group-administered behavioral treatment (GBT) would produce larger improvements in UI compared with no treatment.

Methods

This study was a randomized clinical trial conducted at 3 academic medical centers (University of Alabama at Birmingham; University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; and University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia). It was approved by the institutional review boards at the coordinating center (Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak, Michigan) and each site. All participants provided written informed consent.

Recruitment

We recruited potential participants by mailed letters of invitation to specific populations in the geographical areas surrounding the 3 sites. We purchased mailing lists of women 55 years or older living in targeted counties or communities from InfoUSA, Inc of Omaha, Nebraska.23 Mailing lists were customized for distribution to each of the 3 areas using variables that included zip codes, counties, radius, and race/ethnicity. Interested individuals could mail back a return portion of the recruitment letter or call a toll-free number.

Evaluation and Baseline Assessment

Women who responded to the letter of invitation were initially prescreened by telephone at the coordinating center and then referred to the appropriate research site for full screening and evaluation. This comprised a detailed medical and UI history and baseline questionnaires, including the primary outcome measure (the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Short Form [ICIQ-SF]24) and secondary outcome measures (the Medical, Epidemiologic and Social Aspects of Aging Urinary Incontinence Questionnaire [MESA]25 and the Incontinence Quality of Life Questionnaire [I-QOL]).26 Pelvic examination was conducted to identify pelvic organ prolapse and test PFM strength using the digital test by Brink et al.27 Participants were tested for cognitive impairment using the Mini-Cog28 and for ambulation status using the Timed Up & Go test,29 and a dipstick urinalysis was performed to detect infection and hematuria. Baseline tests included a quantitative cough stress test,30 3-day voiding diary,31 and a 24-hour pad test.32 Inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in the Box.

Box. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

Inclusion Criteria

Female

Age ≥55 years

Ability to read and understand English

Score of ≥3 on the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Short Form, with frequency of leakage a score of ≥1 (“about once a week or less often”) on item 1 and volume of urine loss a score of ≥2 (“a small amount”) on item 2

Self-reported urgency, stress, or mixed incontinence

Symptoms ≥3-month duration

Timed Up & Go test ≤20 seconds

No cognitive impairment (Mini-Cog)

Willingness to undergo pelvic examination

Signed informed consent form

Exclusion Criteria

Nonambulatory (participant confined to bed or wheelchair)

History of bladder, renal, or uterine cancer

Unstable medical condition (as determined by principal investigator)

Daily pelvic pain >3-month duration

Known history of neurological or end-stage diseases (eg, stroke, Parkinson disease, multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, spinal cord tumor or trauma, spina bifida, or symptomatic herniated disk)

Previous treatment for urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse

Current medication for incontinence or overactive bladder

Currently using a vaginal pessary

Other urinary conditions or procedures that may affect continence status (eg, urethral diverticula, previous augmentation cystoplasty or artificial urinary sphincter, or implanted nerve stimulators for urinary symptoms)

Pelvic organ prolapse past the introitus

Evidence of urinary tract infection by dipstick urinalysis

History of ≥2 urinary tract infections within the past year or >1 urinary tract infection within the past 6 months

Postvoid residual urine volume ≥150 mL

Randomization

Eligible women were randomized using a 1:1 ratio to either the GBT group or no treatment (control group). Randomization was carried out separately at each site using a random sequence of block sizes of 2, 4, 6, and 8, with a random assignment of 2 arms within each block to conceal allocation. The randomization scheme was developed by the coordinating center, and the research sites were not aware of the methods used to assign groups.

Intervention

The control group did not receive treatment. However, they were informed that they could receive the GBT class and materials or be referred to an incontinence specialist at the end of the study (12 months).

The GBT was modeled after previously successful randomized clinical trials on prevention of UI18,19 but focused instead on treatment of women with UI.22 This 2-hour bladder health and self-management session, with slide presentations and a booklet, included the following elements: anatomy of the lower urinary tract; bladder and PFM function; anatomic and physiologic basis for continence; types, causes, and effect of UI on quality of life; PFM identification and exercise; bladder training; instruction in evidence-based behavioral strategies, including active PFM contraction during activities that precipitate stress UI and urge suppression strategies18,19,22,33; and coaching to facilitate incorporation of the strategies into their personal routines. After the class, participants were given materials for home use, including a booklet summarizing the bladder health class, a magnet that served as a reminder to continue adherence, an audio CD with a PFM exercise session, and an individualized voiding interval prescription based on their baseline 3-day voiding diary.

To ensure competent and standardized delivery of the treatment, interventionists received a 1-day training. They were certified after role-play demonstrations of the critical components of the intervention. To further ensure consistency of the GBT protocol, all GBT sessions were recorded, and random samples of 11% were reviewed by one of us (T.L.G.) who was not a research site investigator.

Outcome Measures and Evaluation Periods

The primary outcome measure was the change in score on the ICIQ-SF,24 a fully validated 4-item questionnaire (correlated with the 24-hour pad test [r = 0.68] and the Patient Global Impression of Improvement [PGI-I]34 [r = 0.79]). Secondary outcome measures included a 3-day voiding diary, the quantitative cough stress test, the 24-hour pad test, the MESA (15 items, with test-retest reliability of 0.89 and agreement with clinician assessment of 87%), the PFM digital assessment by Brink et al,27 the I-QOL (22 items, with an internal consistency of 0.87-0.93 and a reproducibility intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.80-0.91), and the PGI-I. All participants were evaluated at in-person visits at 3 and 12 months by evaluators (D.K.N. and other nonauthors) who were masked to group assignment and by mail or telephone at 6 and 9 months. Adverse events (AEs) were also assessed at each time point.

Costs and cost-effectiveness were assessed from the payer, participant, and societal perspectives. Payer costs were calculated by summing intervention materials (local rates) and labor (market value).35 Participant-incurred costs for incontinence management (eg, absorbent products and laundry) were estimated by self-reported resource use on the Incontinence Resource Use Questionnaire (IRUQ) and self-reported travel distance to the GBT class and were multiplied by the nationally generalizable unit cost (in 2017 US dollars).36 Indirect costs included participant time to attend the group session (age- and sex-specific wage rates).37

Statistical Analysis

Sample size determination was based on detecting a difference of 3 points in our primary outcome measure, the ICIQ-SF score, with a minimally important difference identified as 2.5 points.38 Based on the literature, we estimated the SD for the control population to be 6.8. We set the significance level to .05 and power at 90% for 2-sided comparison using a 2-sample t test. We also assumed a 25% dropout rate at 3 months and a 35% dropout rate at 12 months. Based on this power analysis, we projected a target sample size of at least 165 completed participants for each group.

This was an intent-to-treat analysis with all randomized participants included. Missing data remained missing and were not replaced. Normally distributed continuous variables are reported as mean (SD) values. Nonnormally distributed variables are reported as median values (interquartile ranges).

The primary outcome, the ICIQ-SF score, was analyzed using a repeated-measures analysis with a dummy variable for the treatment group; dummy variables for 3, 6, 9, and 12 months (baseline as reference); and the treatment × time interaction term as independent variables. The unstructured (5 × 5) covariance matrix was used for the residuals. The point estimates of the regression coefficients and their covariance matrices were used to construct inferences for 3 estimates of interest (namely, the baseline to 3-month difference for each group and the difference between the 2 groups). Both covariate-adjusted analysis and covariate-unadjusted analysis were performed. Given the balance of covariates between the 2 groups, the adjusted and unadjusted results were similar. The unadjusted results are reported. A maximum likelihood approach was used to construct point and interval estimates. The scores at each time point were also examined with Wilcoxon rank sum tests to assess the robustness of the results to the deviation from normality assumption. The analyses using the mean and median values were similar.

Secondary outcome scores were examined at each time point with Wilcoxon rank sum tests for the continuous variables and with Pearson χ2 tests for the individual categorical questions if appropriate (expected frequencies >5 in 80% of cells). Fisher exact tests were used otherwise. Using Pearson χ2 tests, we examined AEs and serious AEs (SAEs) separately.

Within-trial per capita costs from the payer, participant, and societal perspectives were compared between groups using Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios were estimated as the incremental cost divided by the incremental number of successes for GBT compared with control, with success defined as (1) a 70% reduction in UI episode frequency39 and (2) a 3-point decrease in the ICIQ-SF score from baseline. In total, 10 000 bootstrap samples were drawn to construct 95% bias-corrected CIs.

Results

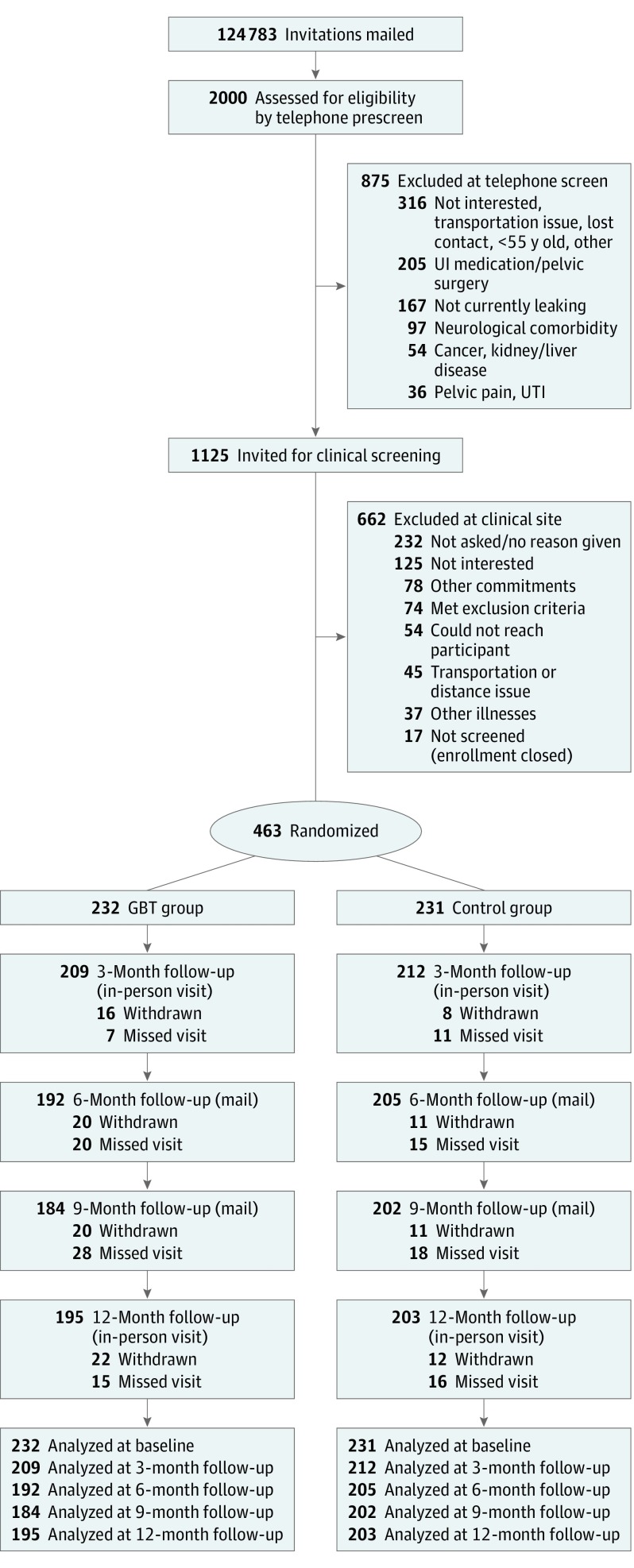

A total of 463 participants were enrolled from 2171 initial mail respondents; 232 were randomized to GBT and 231 to control. Thirty-four of 463 participants (7.3%) withdrew, 22 in GBT (9.5%) and 12 (5.2%) in control (Figure 1); 398 completed the 12-month study.

Figure 1. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Diagram.

GBT indicates group-administered behavioral treatment; UI, urinary incontinence; and UTI, urinary tract infection.

Characteristics of the Sample

The demographic characteristics of the 2 groups were not significantly different. Ages ranged from 55 to 91 years (mean [SD] age, 64 [7] years), and African Americans comprised 46.2% (214 of 463) (Table 1). No significant differences were found between the 2 groups for all baseline values on primary and secondary outcome measures.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Sample.

| Variable | GBT (n = 232) | Control (n = 231) | Statistic | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 64 (7) | 65 (8) | t = 1.60 | .11 |

| Median (range) | 62 (55-91) | 63 (55-87) | ||

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||

| White | 115 (49.6) | 121 (52.4) | χ2 = 3.55 | .73 |

| African American | 113 (48.7) | 101 (43.7) | ||

| Hispanic | 2 (0.9) | 3 (1.3) | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2 (0.9) | 4 (1.7) | ||

| Native American | 0 | 1 (0.4) | ||

| No response or unknown | 0 | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Education, No. (%) | ||||

| <High school graduate | 6 (2.6) | 5 (2.2) | χ2 = 2.26 | .81 |

| High school diploma/GED | 25 (10.8) | 29 (12.6) | ||

| Some college | 80 (34.5) | 71 (30.7) | ||

| Bachelor degree | 57 (24.6) | 68 (29.4) | ||

| Graduate degree | 64 (27.6) | 58 (25.1) | ||

| Employment, No. (%) | ||||

| Full-time | 76 (32.8) | 62 (26.8) | χ2 = 2.62 | .62 |

| Part-time | 26 (11.2) | 23 (10.0) | ||

| Unemployed | 17 (7.3) | 18 (7.8) | ||

| Retired | 100 (43.1) | 112 (48.5) | ||

| Disabled | 13 (5.6) | 16 (6.9) | ||

| Annual household income, $, No. (%) | ||||

| <10 000-25 000 | 47 (20.3) | 52 (22.5) | χ2 = 4.21 | .52 |

| 25 001-50 000 | 60 (25.9) | 68 (29.4) | ||

| 50 001-100 000 | 71 (30.6) | 57 (24.7) | ||

| >100 000 | 37 (15.9) | 30 (13.0) | ||

| No response or unknown | 17 (7.3) | 24 (10.4) | ||

| Living with partner or spouse, No. (%) | 106 (45.7) | 97 (42.0) | χ2 = 0.64 | .42 |

| Medical history, No. (%) | ||||

| BMI ≥30 | 128 (55.2) | 112 (48.5) | χ2 = 2.07 | .15 |

| Previous hysterectomy | 76 (32.8) | 57 (24.7) | χ2 = 3.69 | .06 |

| Ever pregnant | 209 (90.1) | 200 (86.6) | χ2 = 1.38 | .24 |

| Cigarette smoking | 27 (11.6) | 20 (8.7) | χ2 = 1.16 | .28 |

| Arthritis | 135 (58.2) | 145 (62.8) | χ2 = 0.91 | .34 |

| Diabetes | 45 (19.4) | 36 (15.6) | χ2 = 1.21 | .27 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); GBT, group-administered behavioral treatment; GED, general equivalency diploma.

Primary Outcome

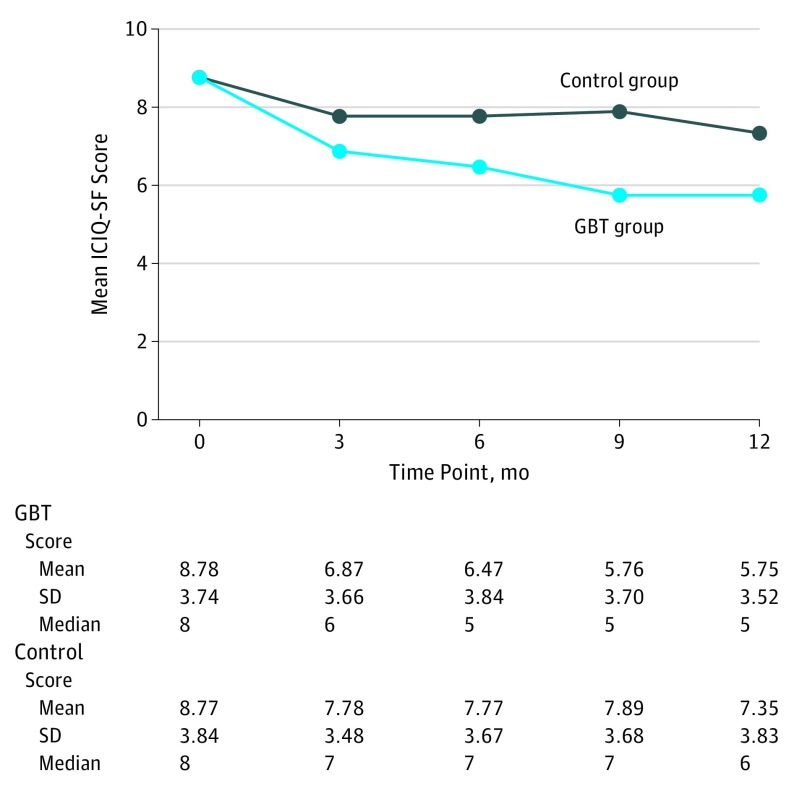

Figure 2 shows the descriptive statistics and change across 5 time points on the ICIQ-SF by treatment group. The overall F score for the treatment × time interaction term was significant (F4460 = 11.62, P < .001). At 3 months, there was a mean 1.94-point reduction (95% CI, −2.33 to −1.55 points) in the GBT group and a mean 0.98-point reduction (95% CI, −1.37 to −0.59 points) in the control group. Therefore, the difference in differences was 0.96 points (95% CI, −1.51 to −0.41 points), which was statistically significant but clinically modest.

Figure 2. Changes in the ICIQ-SF Scores Over Time by Treatment Group.

GBT indicates group-administered behavioral treatment; ICIQ-SF, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Short Form (score range, 0-21; higher scores indicate greater severity of urinary incontinence).

As shown in Figure 2, the ICIQ-SF scores for the GBT group were consistently lower compared with the control group across all time points. For example, the mean (SE) treatment effects at 6, 9, and 12 months were 1.36 (0.32), 2.13 (0.33), and 1.77 (0.31), respectively.

The median score reductions on the ICIQ-SF were 1 point greater for the GBT group than for the control group at 3 months, 2 points greater at 6 and 9 months, and 1 point greater at 12 months, not achieving the projected 3-point difference. Few women, 4.1% (8 of 196) in the GBT group and 1.5% (3 of 203) in the control group, were totally dry (defined as 0 on the ICIQ-SF). Percentage changes in UI episodes based on the 3-day voiding diary were 41.1% for the GBT group vs 5.7% for the control group (P < .001), and the percentages of women who were considered successful (a 70% reduction in UI episode frequency) were 35.3% (65 of 184) in the GBT group vs 22.1% (42 of 190) in the control group (P = .005).

Secondary Outcomes

All secondary outcome measures (Table 2) except PFM strength showed significantly greater improvements in the GBT group than in the control group. For the 3-day voiding diary, the median number of daily voids and UI episodes per day were significantly lower for the GBT group than for the control group at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months. For the 24-hour pad test, the change in urine volume loss was a significantly greater reduction for the GBT group than for the control group at 3 and 12 months. The MESA urge and stress symptom scores were significantly lower for the GBT group than for the control group at 3 and 12 months. For the I-QOL, the GBT group had significantly higher median scores on quality of life compared with the control group at 3 and 12 months. Similarly, for the PGI-I, the GBT group had a significantly greater proportion of women reporting that they were “much better” or “very much better” compared with the control group at 3 and 12 months. Likewise, only 9.7% (19 of 196) of GBT respondents compared with 71.9% (146 of 203) of control respondents reported no change or worse. Regarding patient satisfaction (GBT participants only), 55.9% (118 of 211) and 61.2% (120 of 195), respectively, were “completely satisfied” at 3 months and 6 months, and only 4.7% (10 of 211) and 4.6% (9 of 195) were either “not at all satisfied” or “dissatisfied.” There were no significant differences between the groups at 3 and 12 months on the PFM digital assessment for strength.27

Table 2. Secondary and Cost Outcomes.

| Variable | Baseline | 3-mo Follow-up | 12-mo Follow-up | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBT | Control | P Value | GBT | Control | P Value | GBT | Control | P Value | |

| Measure | |||||||||

| 3-Day voiding diary, median (IQR) | |||||||||

| No. of daily voids | 7.3 (6.0-9.3) |

7.7 (6.3-9.3) |

.12 | 6.3 (5.3-7.3) |

7.7 (6.0-9.0) |

<.001 | 5.3 (5.0-6.7) |

6.7 (5.3-8.3) |

<.001 |

| No. of UI episodes per day | 1.3 (0.7-2.7) |

1.3 (0.3-2.0) |

.12 | 0.7 (0.0-1.3) |

1.0 (0.3-2.0) |

.01 | 0.3 (0.0-1.3) |

0.8 (0.3-2.0) |

<.001 |

| Quantitative cough stress test, % (No./total No.) positive | 46.6 (108/232) |

48.1 (111/231) |

.75 | 31.1 (65/209) |

47.6 (101/212) |

<.001 | 26.3 (51/194) |

42.3 (85/201 |

<.001 |

| 24-Hour pad test, median (IQR), g | 3.8 (0.9-12.8) |

4.8 (1.4-19.7) |

.08 | 2.3 (0.5-7.3) |

4.2 (1.2-17.9) |

.002 | 1.9 (0.5-5.3) |

3.7 (1.0-17.7) |

<.001 |

| MESA score, median (IQR), % | |||||||||

| Urge | 33 (22-50) |

39 (22-56) |

.22 | 28 (17-39) |

33 (17-50) |

<.001 | 20 (11-33) |

28 (17-50) |

<.001 |

| Stress | 44 (30-59) | 44 (30-59) |

.83 | 33 (19-52) |

41 (26-56) |

<.001 | 26 (11-41) |

41 (22-56) |

<.001 |

| PFM digital assessment27 | |||||||||

| Pressure, % (No./total No.) scoring 4 to 6 out of 6 | 49.3 (111/225) |

48.0 (109/227) |

.78 | 52.0 (106/204) |

54.3 (113/208) |

.63 | 56.3 (108/192) |

52.5 (104/198) |

.46 |

| Displacement, % (No./total No.) scoring 4 or 5 out of 5 | 9.7 (22/226) |

11.8 (27/229) |

.45 | 10.8 (22/204) |

14.8 (31/210) |

.23 | 17.3 (33/191) |

11.5 (23/200) |

.10 |

| Duration, median (IQR), s | 4 (2-6) |

4 (2-6) |

.91 | 4 (3-7) |

5 (3-7) |

.66 | 6 (3-8) |

5 (3-8) |

.09 |

| I-QOL score, median (IQR) | 77 (63-88) |

76 (64-88) |

.98 | 86 (77-93) |

83 (68-90) |

<.001 | 92 (83-97) |

85 (72-92) |

<.001 |

| PGI-I, % (No./total No.) much better/very much better | NA | NA | NA | 46.9 (99/211) |

8.1 (17/211) |

<.001 | 64.3 (126/196) |

11.3 (23/203) |

<.001 |

| Patient satisfaction, % (No./total No.) completely/somewhat satisfied | NA | NA | NA | 95.3 (201/211) |

NA | NA | 95.4 (187/196) |

NA | NA |

| Mean per Capita Costs, $ | |||||||||

| Payer costsa | NA | NA | NA | 37.29 | 1.21 | <.001 | 37.29 | 1.21 | <.001 |

| Participant costs | NA | NA | NA | 66.47 | 78.66 | <.001 | 204.92 | 282.78 | <.001 |

| UI management | NA | NA | NA | 50.24 | 78.66 | .003 | 188.69 | 282.78 | .003 |

| Transportation | NA | NA | NA | 16.23 | 0 | <.001 | 16.23 | 0 | <.001 |

| Indirect costs | NA | NA | NA | 59.26 | 0 | <.001 | 59.26 | 0 | <.001 |

| Societal costs totalb | NA | NA | NA | 163.02 | 79.87 | <.001 | 301.47 | 283.99 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: GBT, group-administered behavioral treatment; I-QOL, Incontinence Quality of Life Questionnaire (score range, 0-110; higher scores indicate higher incontinence-specific quality of life); IQR, interquartile range; MESA, Medical, Epidemiologic and Social Aspects of Aging Urinary Incontinence Questionnaire (score range, 0-100; higher scores indicate greater symptom severity); NA, not applicable; PFM, pelvic floor muscle; PGI-I, Patient Global Impression of Improvement; UI, urinary incontinence.

Payer costs include staff labor, intervention materials, and supplies.

Societal costs are the sum of payer, participant, and indirect costs.

Costs and Cost-effectiveness

The GBT group accrued higher payer and societal costs per participant compared with the control group at 3 and 12 months (Table 2 and eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Participant costs, a subset of societal cost, were lower for the GBT group than for the control group at 3 and 12 months because of the lower costs of UI management. The incremental cost per treatment success for the GBT group vs the control group was low at the 3-month evaluation for both the 3-point reduction in the ICIQ-SF score and the 70% reduction in UI episode frequency ($723 and $637, respectively) and was lower at the longer time horizon of 6 months ($268 and $224, respectively), and the GBT group dominated at 12 months (both more effective and less costly by $21 and $17, respectively).

AEs and SAEs

No evidence was found for any differences in frequency of AEs and SAEs between groups. None of the SAEs were attributed to the study. Details are listed in eTable 2 in Supplement 2.

Discussion

This multisite randomized clinical trial in a racially/ethnically diverse sample demonstrated that a one-time GBT session was safe and cost-effective for reducing UI frequency, severity, and bother and improving quality of life for older women with UI when provided by trained interventionists. Improvements in the primary outcome measure were smaller than anticipated, as were the modest between-group differences, which, despite being statistically significant, did not reach the anticipated 3-point difference between groups. This can probably be attributed to the less intensive nature of the single-session group intervention compared with multiple visits to a health professional for individualized behavioral treatment or pharmaceutical or surgical treatment. In addition, the control group underwent the same baseline and follow-up assessments, including history taking, physical examination, 3-day voiding diary, 24-hour pad test, and questionnaires about their symptoms. It is possible that interacting with the research staff or completing the 3-day voiding diary or questionnaires could have enhanced their awareness of bladder symptoms and habits, resulting in increased vigilance and symptom improvements.

Although improvements were modest in magnitude, an overall pattern was seen of significant between-group differences in improvement in UI episodes per day, the quantitative cough stress test, the 24-hour pad test, MESA scores, the I-QOL score, and the PGI-I. A minimally important difference of 2.5 on the ICIQ-SF38 was demonstrated at 9 and 12 months in the GBT group but not in the control group.

This trial showed that health professionals can be trained to master and deliver an evidence-based behavioral treatment program to groups of older community-dwelling women. This noninvasive and inexpensive intervention could be implemented safely in a range of nonmedical settings. It may not represent a definitive intervention for all older women, but it could provide a safe and useful first-line approach that would be of benefit for many. If not fully successful, then the participants would be more informed about bladder problems and can seek other treatment options. In this sense, it could be the first step in a broader strategy to begin with the least invasive therapy and progress as needed to more intensive or invasive treatments.

Because this standardized GBT protocol has been successfully used to prevent UI among continent older women living in the community,18,19 GBT community outreach programs could be considered not only for prevention but also for treatment of UI. One of the future areas to explore is to identify continent women who have a high potential for future UI using the recently developed Continence Index questionnaire,40 which, if successful, would avoid significant investment of time and effort in preventing UI in women who are at low to no risk of developing UI.

Furthermore, although PFM identification and training are an important component of GBT, it does not appear that all women require digital palpation of the PFM to learn the skill needed to achieve improvement, a similar finding in an earlier prevention study.18 Knowledge of strategic and timely use of the PFM may be the essential components of bladder health education.

Cost-effectiveness analyses showed that GBT was a cost-effective method to improve UI symptoms. It incurred low costs and resulted in sustained improvement in UI associated with decreased costs for UI management through 12 months. The cost-effectiveness ratios observed in this trial were low and similar to estimates in other behavioral incontinence interventions41 through 6 months, and the GBT group dominated the control group at 12 months, with lower cost and higher effectiveness.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this study was the recruitment approach. Using mass mailing, we were able to intentionally include zip codes that enhanced inclusion of African American participants, comprising 46.2% of the sample. Another goal of recruiting by mass mailing was to optimize generalizability by offering the opportunity of participation to community-dwelling women who may not have interacted previously with a health care professional for treatment of bladder problems. We recognize that, in seeking a sample broader than the usual clinical population, we might include women whose symptoms were milder.

This trial has some limitations. First, participants and interventionists were not masked to group assignment, a common challenge to studies of behavioral interventions, which require active participation in the self-management strategies. However, the individuals conducting the outcome evaluations were masked to group assignment. Second, the participants were a volunteer sample and thus may not represent the overall population of older women with UI. Third, the primary and some secondary outcomes were based on participant self-report to assess changes in their condition. However, we strategically included more objective measures, such as the quantitative cough stress test and the 24-hour pad test, to complement the validated self-report measures, providing a more comprehensive assessment of outcomes.

Conclusions

The GLADIOLUS study shows that a novel one-time GBT program is a safe and modestly effective first-line approach for reducing UI frequency, severity, and bother and improving quality of life for older women in the community. With its low cost and ease of administration, GBT is a promising first approach to enhancing access to noninvasive behavioral treatment for UI.

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Cost-Effectiveness Outcomes

eTable 2. Incidence of Adverse Events and Serious Adverse Events

References

- 1.Dumoulin C, Adewuyi T, Booth J, et al. Adult conservative management In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Wagg A, Wein A, eds. Incontinence: 6th International Consultation on Incontinence. Bristol, UK: ICI-ICS (International Continence Society); 2017:1443-1628. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coyne KS, Wein A, Nicholson S, Kvasz M, Chen CI, Milsom I. Economic burden of urgency urinary incontinence in the United States: a systematic review. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20(2):130-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qaseem A, Dallas P, Forciea MA, Starkey M, Denberg TD, Shekelle P; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians . Nonsurgical management of urinary incontinence in women: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(6):429-440. doi: 10.7326/M13-2410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bø K, Haakstad LA. Is pelvic floor muscle training effective when taught in a general fitness class in pregnancy? a randomised controlled trial. Physiotherapy. 2011;97(3):190-195. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2010.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pelaez M, Gonzalez-Cerron S, Montejo R, Barakat R. Pelvic floor muscle training included in a pregnancy exercise program is effective in primary prevention of urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Neurourol Urodyn. 2014;33(1):67-71. doi: 10.1002/nau.22381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hilde G, Stær-Jensen J, Siafarikas F, Ellström Engh M, Bø K. Postpartum pelvic floor muscle training and urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial [published correction appears in Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(3):639]. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(6):1231-1238. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alves FK, Riccetto C, Adami DB, et al. A pelvic floor muscle training program in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Maturitas. 2015;81(2):300-305. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dugan SA, Lavender MD, Hebert-Beirne J, Brubaker L. A pelvic floor fitness program for older women with urinary symptoms: a feasibility study. PM R. 2013;5(8):672-676. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill L, Fereday-Smith J, Credgington C, et al. Bladders behaving badly, a randomized controlled trial of group versus individual interventions in the management of female urinary incontinence. J Assoc Chart Physio Women’s Health. 2007;101:30-36. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pereira VS, Correia GN, Driusso P. Individual and group pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment in female stress urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled pilot study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;159(2):465-471. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamb SE, Pepper J, Lall R, et al. Group treatments for sensitive health care problems: a randomised controlled trial of group versus individual physiotherapy sessions for female urinary incontinence. BMC Womens Health. 2009;9:26. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-9-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bø K, Hagen RH, Kvarstein B, Jorgensen J, Larsen S. Pelvic floor muscle exercise for the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence, III: effects of two different degrees of pelvic floor muscle exercises. Neurourol Urodyn. 1990;9:489-502. doi: 10.1002/nau.1930090505 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Felicíssimo MF, Carneiro MM, Saleme CS, Pinto RZ, da Fonseca AM, da Silva-Filho AL. Intensive supervised versus unsupervised pelvic floor muscle training for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a randomized comparative trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(7):835-840. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1125-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Oliveira Camargo F, Rodrigues AM, Arruda RM, Ferreira Sartori MG, Girão MJ, Castro RA. Pelvic floor muscle training in female stress urinary incontinence: comparison between group training and individual treatment using PERFECT assessment scheme. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(12):1455-1462. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-0971-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim H, Yoshida H, Suzuki T. The effects of multidimensional exercise treatment on community-dwelling elderly Japanese women with stress, urge, and mixed urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(10):1165-1172. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janssen CC, Lagro-Janssen AL, Felling AJ. The effects of physiotherapy for female urinary incontinence: individual compared with group treatment. BJU Int. 2001;87(3):201-206. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02040.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tak EC, van Hespen A, van Dommelen P, Hopman-Rock M. Does improved functional performance help to reduce urinary incontinence in institutionalized older women? a multicenter randomized clinical trial. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12:51. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-12-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diokno AC, Sampselle CM, Herzog AR, et al. Prevention of urinary incontinence by behavioral modification program: a randomized, controlled trial among older women in the community. J Urol. 2004;171(3):1165-1171. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000111503.73803.c2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sampselle CM, Newman DK, Miller JM, et al. A randomized controlled trial to compare 2 scalable interventions for lower urinary tract symptom prevention: main outcomes of the TULIP study. J Urol. 2017;197(6):1480-1486. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.12.099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tannenbaum C, Agnew R, Benedetti A, Thomas D, van den Heuvel E. Effectiveness of continence promotion for older women via community organisations: a cluster randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2013;3(12):e004135. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McFall SL, Yerkes AM, Cowan LD. Outcomes of a small group educational intervention for urinary incontinence: health-related quality of life. J Aging Health. 2000;12(3):301-317. doi: 10.1177/089826430001200302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diokno AC, Ocampo MS Jr, Ibrahim IA, Karl CR, Lajiness MJ, Hall SA. Group session teaching of behavioral modification program (BMP) for urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial among incontinent women. Int Urol Nephrol. 2010;42(2):375-381. doi: 10.1007/s11255-009-9626-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Messer KL, Herzog AR, Seng JS, et al. Evaluation of a mass mailing recruitment strategy to obtain a community sample of women for a clinical trial of an incontinence prevention intervention. Int Urol Nephrol. 2006;38(2):255-261. doi: 10.1007/s11255-006-0018-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Avery K, Donovan J, Peters TJ, Shaw C, Gotoh M, Abrams P. ICIQ: a brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2004;23(4):322-330. doi: 10.1002/nau.20041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diokno AC, Dimaculangan RR, Lim EU, Steinert BW. Office based criteria for predicting type II stress incontinence without further evaluation studies. J Urol. 1999;161(4):1263-1267. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)61652-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patrick DL, Martin ML, Bushnell DM, Yalcin I, Wagner TH, Buesching DP. Quality of life of women with urinary incontinence: further development of the Incontinence Quality of Life Instrument (I-QOL) [published correction appears in Urology. 1999;53(5):1072]. Urology. 1999;53(1):71-76. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(98)00454-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brink CA, Wells TJ, Sampselle CM, Taillie ER, Mayer R. A digital test for pelvic muscle strength in women with urinary incontinence. Nurs Res. 1994;43(6):352-356. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199411000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borson S, Scanlan JM, Watanabe J, Tu SP, Lessig M. Simplifying detection of cognitive impairment: comparison of the Mini-Cog and Mini-Mental State Examination in a multiethnic sample. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(5):871-874. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53269.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shumway-Cook A, Brauer S, Woollacott M. Predicting the probability for falls in community-dwelling older adults using the Timed Up & Go Test. Phys Ther. 2000;80(9):896-903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller JM, Ashton-Miller JA, Delancey JO. Quantification of cough-related urine loss using the paper towel test. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91(5, pt 1):705-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Locher JL, Goode PS, Roth DL, Worrell RL, Burgio KL. Reliability assessment of the bladder diary for urinary incontinence in older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(1):M32-M35. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.1.M32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lose G, Jørgensen L, Thunedborg P. 24-Hour home pad weighing test versus 1-hour ward test in the assessment of mild stress incontinence. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1989;68(3):211-215. doi: 10.3109/00016348909020991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burgio KL, Locher JL, Goode PS, et al. Behavioral vs drug treatment for urge urinary incontinence in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280(23):1995-2000. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.23.1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yalcin I, Bump RC. Validation of two global impression questionnaires for incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(1):98-101. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor May 2016 national occupational employment and wages estimates, United States. https://www.bls.gov/oes/2016/may/oes_nat.htm. Last modified March 31, 2017. Accessed January 2017.

- 36.Subak L, Van Den Eeden S, Thom D, Creasman JM, Brown JS; Reproductive Risks for Incontinence Study at Kaiser Research Group . Urinary incontinence in women: Direct costs of routine care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(6):596.e1-596.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor Table 3: median usual weekly earnings of full-time wage and salary workers by age, race, Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, and sex, not seasonally adjusted. https://www.bls.gov/webapps/legacy/cpswktab3.htm. Last modified September 16, 2015. Accessed January 2017.

- 38.Nyström E, Sjöström M, Stenlund H, Samuelsson E. ICIQ symptom and quality of life instruments measure clinically relevant improvements in women with stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2015;34(8):747-751. doi: 10.1002/nau.22657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yalcin I, Peng G, Viktrup L, Bump RC. Reductions in stress urinary incontinence episodes: what is clinically important for women? Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29(3):344-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diokno AC, Ogunyemi T, Siadat MR, Arslanturk S, Killinger KA. Continence Index: a new screening questionnaire to predict the probability of future incontinence in older women in the community. Int Urol Nephrol. 2015;47(7):1091-1097. doi: 10.1007/s11255-015-1006-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wagner TH, Moore KH, Subak LL, deWatcher S, Dudding T. Economics of urinary and fecal incontinence and prolapse In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Wagg A, Wein A, eds. Incontinence: 6th International Consultation on Incontinence. Bristol, UK: ICI-ICS (International Continence Society); 2017:2479-2511. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Cost-Effectiveness Outcomes

eTable 2. Incidence of Adverse Events and Serious Adverse Events