This randomized clinical trial examines outcomes of participation in an individually designed single-patient multi-crossover (n-of-1) trial supported by a mobile app compared with usual care among patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain.

Key Points

Question

Does participation in an individually designed single-patient multi-crossover (n-of-1) trial improve pain-related or patient-engagement outcomes compared with usual care among patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain?

Findings

This randomized clinical trial found no significant difference in pain-related interference at 6-month follow-up between 108 patients randomized to an n-of-1 trial supported by a mobile app and 107 patients randomized to usual care. Medication-related shared decision making was significantly better in the n-of-1 group, and the n-of-1 participants were highly satisfied with the mobile app.

Meaning

In this study, n-of-1 trials supported by a mobile app were feasible and associated with a satisfactory user experience, but participation did not significantly improve pain interference.

Abstract

Importance

Individually designed single-patient multi-crossover (n-of-1) trials can facilitate tailoring of treatments directed at various conditions, including chronic musculoskeletal pain (CMSP) but are potentially burdensome, which may limit uptake in research and practice.

Objectives

To determine whether patients randomized to participate in an n-of-1 trial supported by a mobile health (mHealth) app would experience less pain and improved global health, adherence, satisfaction, and shared decision making compared with patients assigned to usual care.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This randomized clinical trial compared participation in an individualized, mHealth-supported n-of-1 trial vs usual care. The participating 215 patients had CMSP for at least 6 weeks, had a smartphone or tablet with a data plan, were enrolled in northern California from July 2014 through July 2016, and were followed for up to 1 year by 48 clinicians in academic, community, Veterans Affairs, and military settings.

Interventions

Intervention patients met with their clinicians and used a desktop interface to select treatments and trial parameters for an n-of-1 trial comparing 2 pain-management regimens. The mHealth app provided reminders to take designated treatments on assigned days and to upload responses to daily questions on pain and treatment-associated adverse effects. Control patients received care as usual.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was change in the PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) pain-related interference 8-item short-form scale (full scale range, 41-78) from baseline to 6 months. Secondary outcomes included patient-reported pain intensity, overall health, analgesic adherence, trust in clinician, satisfaction with care, medication-related shared decision making, and, for the n-of-1 group only, participant engagement and experience.

Results

Among 215 patients (108 randomized to the n-of-1 intervention and 107 to control), 102 (47%) were women, and the mean (SD) age was 55.5 (11.1) years. At the 6-month follow-up, pain interference was reduced in both groups, though there was no difference between the intervention and control groups (−1.36 points; 95% CI, −2.91 to 0.19 points; P = .09). There were no advantages in secondary outcomes for intervention patients vs control patients except for higher medication-related shared decision making at 6 months (between-group difference, 11.9 points; 95% CI, 2.6-21.2 points; P = .01). Among patients assigned to the n-of-1 group, 88% (n = 86) affirmed that the mHealth app could help people like them manage their pain.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this population of patients with CMSP, mHealth-supported n-of-1 trials were feasible and associated with a satisfactory user experience, but n-of-1 trial participation did not significantly improve pain interference at 6 months vs usual care.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02116621

Introduction

Individually designed single-patient multi-crossover (n-of-1) trials are experiments in which patients switch between 2 or more treatments.1 In contrast with parallel-group randomized clinical trials, which estimate average treatment effects in the population studied, the n-of-1 crossover design permits estimation of treatment effects for each individual participant.2,3 Additionally, n-of-1 trials are most appropriate for chronic stable diseases and for treatments with rapid onset and minimal carryover following treatment switching.4 Although used in diverse conditions,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 n-of-1 trials have not been widely adopted, in part because they have been perceived by clinicians and patients as requiring too much time and effort.13

Patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain (CMSP) are at high risk of physical disability, emotional distress, and work absenteeism.14,15,16 Analgesic medications are the traditional mainstay of CMSP treatment, but opioid-related concerns17 have prompted clinicians to consider alternatives.18,19 We hypothesized that participation in an n-of-1 trial might benefit patients with CMSP, either by steering patients toward more personally effective therapies or by expanding patient involvement in care.20

To assess the impact of n-of-1 trials as a decision-making and patient-engagement strategy in chronic pain, we conducted a randomized clinical trial, assigning patients with CMSP to participate in individually designed n-of-1 trials or to receive usual care. We hypothesized that n-of-1 trial participants would report improved outcomes.21 We also sought to determine whether use of a mobile health (mHealth) app would address barriers to n-of-1 trial participation and would be evaluated positively by patients.

Methods

Overview

As described elsewhere,22 the Personalized Research for Monitoring Pain Treatment study compared assignment to an mHealth-supported n-of-1 trial vs usual care in diverse primary care settings. The study sought to assess the possible benefits of participating in an n-of-1 trial, not to assess the superiority or inferiority of any particular treatment. Enrollment began in July 2014 and, in an effort to achieve the target sample of 244 patients, was extended from January 2016 to July 2016. Follow-up ended in May 2017. The primary study outcome was pain-related interference 6 months after study entry (full scale range, 41-78).

Setting and Participants

The study was conducted in northern California with recruitment at the University of California, Davis (UC Davis) Primary Care Network; UC Davis Family Medicine Clinic; UC Davis General Medicine Clinic; Veterans Affairs Northern California Health Care System; and David Grant Medical Center at Travis Air Force Base. Institutional review board approval, as well as written informed consent from all patients, was obtained at each site. The trial protocol for this study is available in Supplement 1.

Participating clinicians included 21 general internists, 21 family physicians, 2 Veterans Affairs pain specialty physicians practicing in close association with primary care, 1 nurse practitioner, 2 physician assistants, and 1 clinical pharmacist. Of the participating clinicians, 60% (n = 29) were recruited from UC Davis, the mean (SD) age was 44 (10) years; the mean (SD) time in practice was 12.5 (9.5) years, and 50% (n = 24) were female. Clinicians received a small participation incentive (ie, $100 gift card for each patient completing the 6-month follow-up). The median number of study patients per clinician was 3.

Every 6 months, information services personnel at participating sites generated a list of patients with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision musculoskeletal pain diagnosis who were under the care of an enrolled clinician. These patients (n = 10 867) were sent a letter describing the study and inviting them to contact research staff. Interested patients were screened by telephone, and English-speaking adults (18-75 years old) were potentially eligible if they had musculoskeletal pain for at least 6 weeks at the time of screening, had a smartphone or tablet (Android or iOS) with a data plan, and reported a score of 4 or higher out of 10 on at least 1 item of the 3-item pain, enjoyment, and general activity questionnaire.23

Patients were excluded if they had cancer treatment within the past 5 years, life expectancy less than 2 years, a serious psychiatric condition, evidence of drug or alcohol abuse, or had tried 5 or more analgesic medications and had to discontinue use owing to lack of effectiveness or poor tolerance. Ultimately, 215 patients participated in the study. Patients received participation incentives worth up to $150 for n-of-1 participants and $60 for usual care controls.

Randomization

The study statistician generated a randomization schedule using the R statistical package.24 Clinicians were notified of the patient’s group assignment 1 week prior to the visit, but neither patients nor research staff became aware of the patient’s allocation until the research assistant opened an opaque envelope in the clinician’s office at the baseline visit. Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio, blocked within clinician, with block sizes varying randomly from 4 to 6. All patients received a chronic pain self-management booklet produced by UC Davis.

Intervention

After administering baseline questionnaires, the research assistant accompanied the patient into the examination room to facilitate n-of-1 trial setup via a desktop interface. Based on the clinician’s judgment and the patient’s preferences, the clinician-patient dyad selected from 8 treatment categories: (1) acetaminophen; (2) any nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; (3) acetaminophen/codeine; (4) acetaminophen/hydrocodone; (5) acetaminophen/oxycodone; (6) tramadol; (7) complementary/alternative treatments such as massage, meditation, or physical exercise; or (8) current ongoing therapy (or no therapy). Short-acting opioids were included as options because they are in common use in primary care and because it was believed that some patients might benefit from eliminating them.25

Treatment regimens for comparison (eg, treatment A and treatment B) could be single agents (eg, acetaminophen) or combinations (eg, acetaminophen plus tramadol). Trials could be structured to compare treatments between categories (eg, acetaminophen vs acupuncture) or treatments within category (eg, massage vs yoga). Dyads also chose the duration of each treatment period (1 or 2 weeks), the number of paired comparisons (2, 3, or 4), and the start date. Trials could last 4, 6, 8, or 12 weeks.

Trial parameters were sent to the Trialist system (an open-source mobile app supported by a server-based back end developed by OpenmHealth.org) on the patient’s mobile device. The system randomly chose a balanced treatment sequence (eg, ABAB); alerted the patient when to begin each treatment; and sent a daily questionnaire covering pain on average, pain interference with enjoyment of life, and pain interference with daily activities (each self-assessed over the past 24 hours), as well as 5 potential adverse effects of treatment (drowsiness, fatigue, constipation, sleep problems, and cognitive impairment). To improve study adherence, study staff contacted patients by telephone or email for failing to start a trial as scheduled or for not completing at least 4 daily questionnaires per week (out of 7 expected).

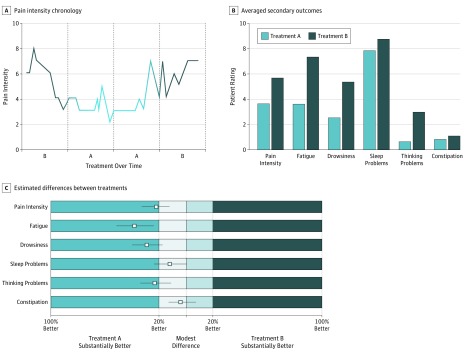

At trial completion, patients were asked to meet with their clinician for a results review visit to discuss the n-of-1 trial experience while addressing any new or ongoing clinical concerns. Each dyad was provided graphs depicting their n-of-1 trial results, which were generated by comparing outcomes between regimens (treatment A vs treatment B), first descriptively (Figure 1A and B) and then using Bayesian models yielding absolute differences with 95% credible intervals (Figure 1C) and probabilities of small, medium, and large effects. To aid in interpretation, physicians had access to online instructional videos. Patients unable to schedule a results review visit within 8 weeks of n-of-1 trial completion could review results by telephone or email.

Figure 1. Examples of Graphical Output Provided to Patients and Their Clinicians in the n-of-1 Arm During Results Review Visits.

Patients and clinicians were provided with 6 graphs during the results review visit; 3 are depicted here. The graphs were intended to be devoid of jargon and easily understood and interpreted by patients and clinicians. Clinicians were provided access to brief web-based training videos to assist them in interpreting the graphs for their patients. The patient in this example compared acetaminophen as treatment A (shown in light blue) with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug as treatment B (shown in dark blue). The graphs in panels B and C depict 6 patient-centered outcomes (pain intensity, fatigue, drowsiness, sleep problems, thinking problems, and constipation) comparing treatment A with treatment B. A, The daily ratings on a 0- to 10-point scale for pain intensity, which were entered into the Trialist app by the patient. Zero indicates no pain, and 10 the highest level of pain. Each data point indicates 1 day. B, The average of daily ratings on a 0-10 scale for each outcome. Zero designates the best outcome. C, The outcomes are shown as squares representing point estimates for relative improvement, with lines representing the 95% credible intervals, and color shading and labeling to facilitate decision making. The analysis in this panel was based on a Bayesian model that estimated the posterior distribution of the difference between symptom scores comparing treatment A with treatment B.

Control Condition

Patients assigned to the control group attended a baseline clinic visit where they completed assessments in the waiting room under the supervision of the study research assistant. Otherwise they received care as usual.

Outcomes and Follow-up

All study patients were expected to complete outcome assessments at baseline and at approximately 3, 6, and 12 months. The primary prespecified outcome was change in the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) pain-related interference 8-item short-form scale (full scale range, 41-78) from baseline to 6 months.26,27 We focused on the 6-month interval to allow time for patients to complete their n-of-1 trial, complete a results review visit, settle into a new therapeutic regimen based on trial results, and apply skills learned during the n-of-1 experience (eg, being aware of exacerbating and alleviating factors). We assessed this outcome as the mean difference between intervention and control groups. In an analysis that was not prespecified, we also assessed the difference in the proportion of patients achieving a 5-point improvement in PROMIS pain-related interference. A 5-point improvement represented a statistically significant change at the individual level given the measured reliability (0.95) and SD (5.8) in our sample.28,29

Secondary outcomes included pain interference at 3 and 12 months,30 as well as the following outcomes measured at 3, 6, and 12 months: pain intensity using the PROMIS 3a short form30; physical and mental global health using the 10-item PROMIS Global Health scale, version 1.0-1.131; analgesic adherence (with overuse and underuse scores) using 4 items from the Pain Medication in Primary Care Patient questionnaire32; patient-clinician relationship assessed using the 11-item Trust in Physician scale33; and satisfaction with pain care (with scores for satisfaction with information about pain and its treatment [5 items], medical care [5 items], and current pain medications [8 items]).34 Among patients who reported talking with the clinician “who prescribes your pain treatments” about “starting or stopping a prescription medication…in the last 12 months,” we also assessed medication-related shared decision making using a 3-item scale from the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey at 6 and 12 months.35,36

Patients’ n-of-1 Experiences

To characterize experiences of patients using the Trialist app, we asked intervention group patients to rate the helpfulness of the Trialist app along 5 dimensions, from 1 (extremely helpful) to 5 (not at all helpful). In addition, patients were asked “Do you believe the Trialist app could help people like you manage their pain (yes or no)?” We also asked patients to rate 10 statements from the System Usability Scale,37 from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). See Table 1 for specific wording.

Table 1. Trialist App Acceptability and Satisfaction Questionnaire Responses for n-of-1 Trial Patients.

| Characteristic | Patients Responding Affirmatively, No. (%) (n = 95)a |

|---|---|

| Helpfulness of the Trialist app | |

| Keeping track of your pain | 77 (81) |

| Working closely with clinician to achieve your treatment goals | 50 (54) |

| Identifying different pain triggers | 46 (49) |

| Noticing things that help your pain feel better | 55 (58) |

| Having more confidence in the pain management approach that you will follow going forward | 56 (60) |

| Trialist app usability/functionality | |

| I would like to use the Trialist app frequently | 63 (66) |

| I found the Trialist app unnecessarily complex | 2 (2) |

| I thought the Trialist app was easy to use | 93 (98) |

| I would need the support of a technical person to be able to use the Trialist app | 4 (4) |

| I found the various functions in the Trialist app were well integrated | 73 (77) |

| I thought there was too much inconsistency in the Trialist app | 6 (6) |

| I would imagine most people would learn to the Trialist app very quickly | 90 (95) |

| I found the Trialist app awkward to use | 3 (3) |

| I felt very confident using the Trialist app | 85 (89) |

| I needed to learn a lot of things before I could get going with the Trialist app | 3 (3) |

Percentages represent the proportion of affirmative responses, defined as “extremely or very helpful” and as “strongly agree” or “agree,” among patients completing an n-of-1 trial and who responded to the specific survey question. Item nonresponse ranged from 0 to 5 patients.

Statistical Analysis and Power

The primary analysis comparing n-of-1 vs usual care followed the intention-to-treat principle, accounting for all participants as randomized. The planned sample size of 244 was calculated based on the assumption of a minimally important difference of 0.4 SDs on the PROMIS pain-related interference scale.29 Assuming a 10% dropout rate, 122 patients in each group would provide 80% power to detect a 0.36-SD (3.6-point) difference in mean T scores (general population mean, 50; SD, 10) using a 2-group t test with 2-sided alpha equaling 0.05.

Outcomes were analyzed with longitudinal mixed effects Gaussian models combining baseline, 3-, 6-, and 12-month measurements using time, treatment, and a time-by-treatment interaction as fixed effects, and clinician and patient as random effects. Such models account properly for missing outcomes when the probability of missingness depends on the values of previous outcomes.38 Because Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey questions assessing medication-related shared decision making were applicable only to patients who had talked with their clinicians about starting or stopping treatment with a medication in the past 12 months, this outcome was assessed by comparing mean scale scores (with 95% CIs) for intervention and control patients at 6 and 12 months. We also conducted exploratory analyses examining interactions between the intervention and covariates including age, sex, race, ethnicity, marital status, education, employment status, study site, baseline opioid use, and CMSP pain category (eg, axial [ie, neck/back], extremity, other). All model assumptions were checked with standard regression diagnostics. Patients missing the primary outcome at 3, 6, and 12 months were similar demographically to those not missing the primary outcome, but they were less likely to be taking opioids at baseline and had slightly worse baseline health (eTable in Supplement 2). In regressions that adjusted for missingness, results were not substantially different than in the base case. All analyses were performed using R software, version 3.3.1 (R Foundation).

Results

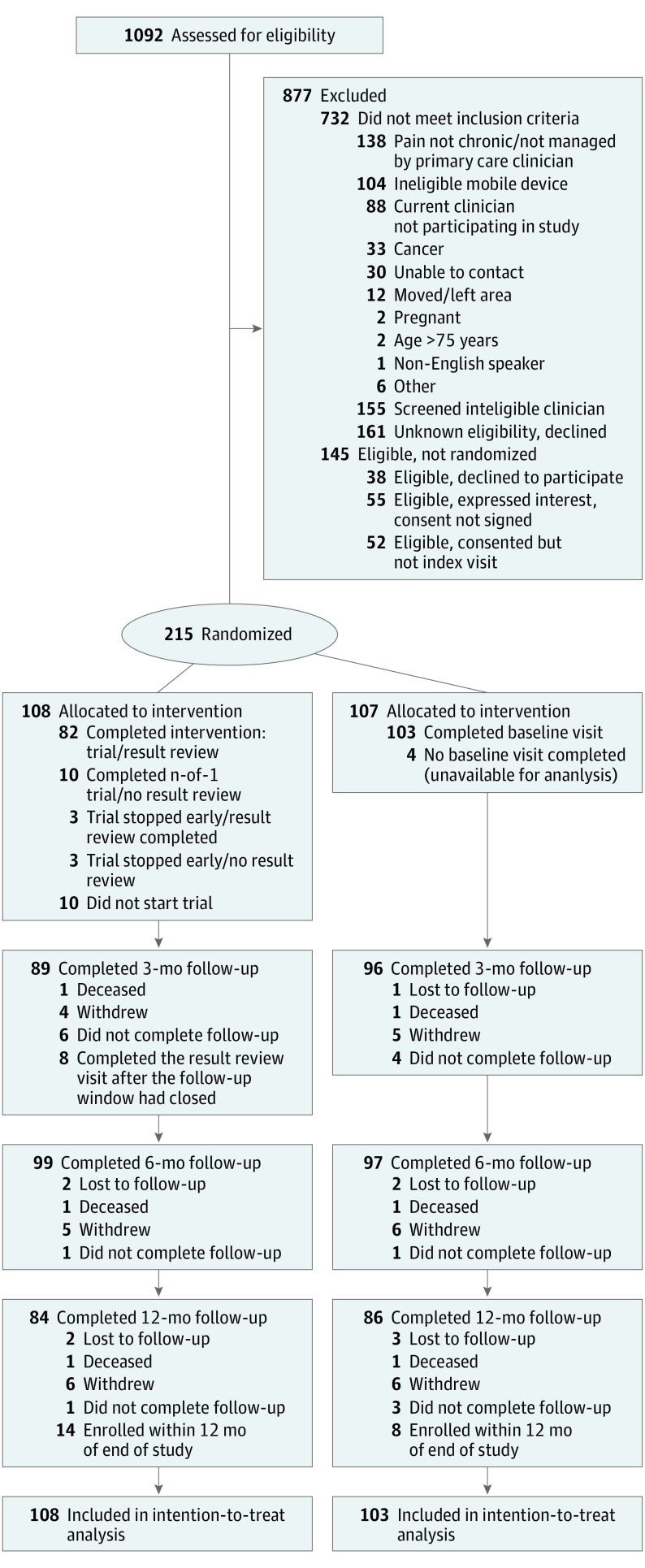

Of 1092 patients assessed for eligibility, 732 did not meet inclusion criteria, and 145 were eligible but not randomized (Figure 2). The remaining 215 patients were randomized, 108 to the intervention group and 107 to control, including 22 who were enrolled too late for follow-up past the 6-month mark and were therefore missing 12-month (secondary) outcomes. Among participants, mean (SD) age was 55.5 (11.1) years, 47% (n = 102) were women, 26% (n = 56) were nonwhite, 55% (n = 119) lacked a college degree, 52% (n = 112) were not currently working, and 45% (n = 86) were on opioids at baseline (Table 2). As expected in a population with CMSP, pain interference (overall mean [SD], 64.3 [5.8]), pain intensity (53.7 [5.2]), and global physical and mental health (41.6 [6.2] and 44.1 [8.6], respectively) were worse than US norms.27,30 Compared with controls, intervention patients had better global physical health and greater satisfaction with medical care, but otherwise there were no meaningful differences in baseline characteristics (Table 2).

Figure 2. Enrollment Flowchart for Personalized Research for Monitoring Pain Treatment Study Patient Recruitment and Enrollment.

Patients who no longer wished to continue in the study were classified as withdrew. Patients who could not be located were classified as lost to follow-up, while those missing data at a particular follow-up time point were classified as did not complete follow-up. Patients who had not completed the intervention before the 3-month window ended were classified as completed the results review visit after the follow-up window had closed. Patients enrolled at the end of the recruitment period and not followed beyond 6 months were classified as enrolled within 12 months of end of study.

Table 2. Baseline Characteristics of PREEMPT Study Participants by Treatment Group.

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 215) |

Intervention (n = 108) |

Control (n = 107) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, No. (%) | |||

| Male | 113 (53) | 58 (54) | 55 (51) |

| Female | 102 (47) | 50 (46) | 52 (49) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 55.5 (11.1) | 55.4 (10.8) | 55.6 (11.5) |

| Race, No. (%) | |||

| White | 155 (74) | 75 (69) | 80 (78) |

| Black or African American | 27 (13) | 12 (11) | 15 (15) |

| Asian | 12 (6) | 8 (7) | 4 (4) |

| Other | 17 (8) | 13 (12) | 4 (4) |

| Latino, No. (%) | 24 (11) | 16 (15) | 8 (8) |

| Marital status, No. (%) | |||

| Married or living with partner | 142 (67) | 75 (69) | 67 (65) |

| Widowed | 10 (5) | 5 (5) | 5 (5) |

| Divorced or separated | 43 (20) | 21 (19) | 22 (21) |

| Never married | 16 (8) | 7 (7) | 9 (9) |

| Education, No. (%) | |||

| High school diploma or less | 16 (7) | 6 (6) | 10 (9) |

| Some college and/or associate degree and/or vocational training | 103 (48) | 54 (50) | 49 (46) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 56 (26) | 23 (21) | 33 (31) |

| Master’s or doctoral or professional degree | 40 (19) | 25 (23) | 15 (14) |

| Employment, No. (%) | |||

| Full time (≥35 h/wk) | 85 (40) | 40 (37) | 45 (42) |

| Part time (<35 h/wk) | 18 (8) | 12 (11) | 6 (6) |

| Not employed or retired or unable to work | 112 (52) | 56 (52) | 56 (52) |

| Practice location, No. (%) | |||

| UC Davis and/or Primary Care Network | 110 (51) | 56 (52) | 54 (51) |

| VANCHCS or David Grant, Travis AFB | 105 (49) | 52 (48) | 53 (49) |

| Pain diagnosis, No. (%) | |||

| Axial | 90 (42) | 42 (39) | 48 (45) |

| Extremity | 84 (39) | 45 (42) | 39 (36) |

| Other or unknown | 41 (19) | 21 (19) | 20 (19) |

| PEG scorea | 6.0 (1.9) | 5.8 (2.0) | 6.1 (1.8) |

| Baseline opioid use, No. (%)b | 86 (45) | 41 (42) | 45 (48) |

| Primary and secondary outcome scores, mean (SD)c | |||

| Pain interferenced,e | 64.3 (5.8) | 64.0 (5.9) | 64.7 (5.8) |

| Pain intensityf | 53.7 (5.2) | 53.5 (5.4) | 53.8 (5.1) |

| Global physical healthg | 41.6 (6.2) | 42.5 (6.8) | 40.6 (5.5)h |

| Global mental healthi | 44.1 (8.6) | 44.9 (9.1) | 43.2 (7.9) |

| Analgesic adherence (overuse)j | 89.8 (12.9) | 90.2 (12.4) | 89.4 (13.4) |

| Analgesic adherence (underuse)k | 75.4 (23.4) | 75.2 (22.3) | 75.6 (24.6) |

| Trust in clinicianl | 76.1 (16.4) | 76.8 (15.8) | 75.3 (17.1) |

| Satisfaction with pain informationm | 50.6 (38.2) | 50.5 (38.8) | 50.7 (37.8) |

| Satisfaction with medical caren | 82.2 (17.7) | 84.7 (15.7) | 79.5 (19.2) h |

| Satisfaction with pain medicationo | 64.4 (22.8) | 65.2 (22.1) | 63.4 (23.6) |

| Medication-related shared decision-makingp | 74.6 (23.9) | 74.3 (23.8) | 75.0 (24.3) |

Abbreviations: AFB, air force base; PEG, pain, enjoyment, general activity; PREEMPT, Personalized Research for Monitoring Pain Treatment; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; UC Davis, University of California, Davis; VANCHCS, Veterans Affairs, Northern California Health Care System.

In contrast to other measures, which were obtained at the baseline visit, PEG scores were obtained at screening. Mean scores were clinically comparable and statistically nonsignificant (P = .31).

Baseline opioid use was assessed via medical record review among patients who provided permission for such review (n = 190 total; 97 in the intervention group and 93 in control).

All scales had a theoretical range of 0 to 100 except for PEG (range, 0-10); in all cases 0 was the best possible score.

Primary outcome.

PROMIS pain-interference scores in this sample ranged from 50.3 to 77.0. The possible range, based on the raw score to T-score conversion table in the PROMIS Pain Interference Scoring Manual (https://www.assessmentcenter.net/manuals.aspx), is 41.0 to 78.3. Higher scores indicate greater pain interference.

PROMIS pain intensity scores in this sample ranged from 40.5 to 69.4. Higher scores indicate greater pain intensity.

PROMIS global physical health scores in this sample ranged from 23.7 to 62.5. Higher scores indicate better physical health.

Mean differences between n-of-1 and control groups, P < .05.

PROMIS global mental health scores in this sample ranged from 21.3 to 63.6. Higher scores indicate better mental health.

Scores in this sample ranged from 37.5 to 100. Higher scores indicate greater adherence and less overuse of medication.

Scores in this sample ranged from 0 to 100. Higher scores indicate greater adherence and less underuse of medication.

Scores in this sample ranged from 20.5 to 100. Higher scores indicate greater trust.

Scores in this sample ranged from 0 to 100. Higher scores indicate greater satisfaction.

Scores in this sample ranged from 15 to 100. Higher scores indicate greater satisfaction.

Scores in this sample ranged from 0 to 100. Higher scores indicate greater satisfaction.

Medication-related shared decision-making scores, which were computed only for patients who reported discussing medications with their clinician in the past 12 mo, ranged from 0 to 100 in this sample. Higher scores indicate more shared decision making.

Among the 108 intervention patients, 98 initiated and 95 completed an n-of-1 trial. Completed trials ranged from 4 to 12 weeks (mode, 8 weeks). Of the treatment categories, 31% of patients incorporated acetaminophen, 57% a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, 24% tramadol, 26% incorporated an opioid (eg, codeine, hydrocodone, or oxycodone combination product), and 48% incorporated 1 or more nonpharmacologic, complementary, or alternative treatments (eg, exercise, physical therapy, tai chi, massage, acupuncture, mindfulness meditation). Results review visits were completed in person (n = 80), by mail (n = 13), or through an electronic patient portal (n = 2). Among patients finishing their n-of-1 trial, the median daily questionnaires completed was 71% (n = 95).

Primary Outcome

In the intention-to-treat analysis of the 6-month PROMIS pain-interference scale, patients in the intervention group improved slightly more than those in the control group, but there was no significant difference in change from baseline between the intervention and control groups (−1.36 points; 95% CI, −2.91 to 0.19 points; P = .09) (Table 3). Intervention patients were more likely than controls to register an improvement of 5 or more points in PROMIS pain interference at 6 months (34% [n = 37] vs 22% [n = 23]; P = .05).

Table 3. Change in Primary and Secondary Outcomes From Baseline and Between-Group Differences.

| Time of Observation, mo | Intervention | Control | Difference | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Estimate (95% CI) | No. | Estimate (95% CI) | No. | Estimate (95% CI) | Time Specific | Overall | |

| Pain-related interference | .21 | |||||||

| 3 | 89 | −2.70 (−3.83 to −1.57)a | 96 | −1.91 (−3.02 to −0.81)a | 185 | −0.79 (−2.37 to 0.80) | .33 | |

| 6 | 99 | −3.22 (−4.31 to −2.13)a | 97 | −1.85 (−2.96 to −0.75)b | 196 | −1.36 (−2.91 to 0.19) | .09 | |

| 12 | 84 | −2.67 (−3.82 to −1.52)a | 86 | −2.83 (−3.98 to −1.68)a | 170 | 0.16 (−1.47 to 1.79) | .85 | |

| Pain intensity | .06 | |||||||

| 3 | 89 | −1.60 (−2.67 to −0.54)b | 96 | −1.92 (−2.96 to −0.87)a | 185 | 0.31 (−1.18 to 1.81) | .68 | |

| 6 | 99 | −2.86 (−3.89 to −1.83)a | 97 | −1.46 (−2.50 to −0.41)b | 196 | −1.41 (−2.87 to 0.06) | .06 | |

| 12 | 84 | −3.00 (−4.08 to −1.91)a | 86 | −1.76 (−2.85 to −0.67)b | 170 | −1.24 (−2.77 to 0.30) | .12 | |

| Overall physical health | .86 | |||||||

| 3 | 88 | 0.73 (−0.21 to 1.67) | 96 | 0.44 (−0.48 to 1.35) | 184 | 0.30 (−1.01 to 1.61) | .66 | |

| 6 | 99 | 0.13 (−0.77 to 1.03) | 97 | 0.30 (−0.61 to 1.21) | 196 | −0.17 (−1.45 to 1.12) | .80 | |

| 12 | 84 | 0.16 (−0.79 to 1.12) | 86 | 0.42 (−0.53 to 1.37) | 170 | −0.26 (−1.61 to 1.09) | .71 | |

| Overall mental health | .35 | |||||||

| 3 | 88 | −0.35 (−1.71 to 1.00) | 96 | 0.30 (−1.02 to 1.63) | 184 | −0.66 (−2.55 to 1.24) | .50 | |

| 6 | 99 | 0.21 (−1.09 to 1.52) | 97 | −0.72 (−2.04 to 0.60) | 196 | 0.93 (−0.92 to 2.79) | .33 | |

| 12 | 84 | 0.36 (−1.01 to 1.74) | 86 | −0.39 (−1.76 to 0.98) | 170 | 0.76 (−1.19 to 2.70) | .45 | |

| Analgesic adherence (overuse) | .70 | |||||||

| 3 | 88 | 1.40 (−1.18 to 3.98) | 94 | 0.35 (−2.15 to 2.85) | 182 | 1.05 (−2.54 to 4.64) | .57 | |

| 6 | 94 | 1.77 (−0.75 to 4.30) | 92 | −0.13 (−2.64 to 2.39) | 186 | 1.90 (−1.66 to 5.47) | .30 | |

| 12 | 83 | 1.61 (−1.02 to 4.24) | 84 | 1.53 (−1.06 to 4.12) | 167 | 0.08 (−3.61 to 3.77) | .96 | |

| Analgesic adherence (underuse) | .20 | |||||||

| 3 | 88 | 2.53 (−2.46 to 7.52) | 94 | −1.71 (−6.56 to 3.15) | 182 | 4.24 (−2.73 to 11.20) | .23 | |

| 6 | 95 | 1.88 (−3.00 to 6.76) | 93 | −2.76 (−7.63 to 2.11) | 188 | 4.64 (−2.25 to 11.54) | .19 | |

| 12 | 83 | −3.53 (−8.62 to 1.56) | 84 | −1.62 (−6.66 to 3.42) | 167 | −1.91 (−9.07 to 5.26) | .60 | |

| Trust in clinician | .66 | |||||||

| 3 | 88 | −2.49 (−5.44 to 0.46)c | 96 | −4.25 (−7.13 to −1.36)b | 184 | 1.76 (−2.37 to 5.89) | .40 | |

| 6 | 99 | −2.30 (−5.14 to 0.54) | 96 | −4.84 (−7.73 to −1.96)c | 195 | 2.55 (−1.50 to 6.60) | .22 | |

| 12 | 84 | −4.00 (−7.00 to −0.99)b | 86 | −5.53 (−8.52 to −2.54)a | 170 | 1.53 (−2.70 to 5.77) | .48 | |

| Satisfaction with pain information | .44 | |||||||

| 3 | 89 | 4.41 (−3.18 to 12.00) | 96 | −3.36 (−10.84 to 4.11) | 185 | 7.77 (−2.87 to 18.42) | .15 | |

| 6 | 99 | 11.28 (3.95 to 18.61)b | 96 | 3.99 (−3.47 to 11.45) | 195 | 7.29 (−3.16 to 17.75) | .17 | |

| 12 | 84 | 9.02 (1.28 to 16.76)d | 86 | 4.89 (−2.84 to 12.63) | 170 | 4.13 (−6.81 to 15.07) | .46 | |

| Satisfaction with medical care | .58 | |||||||

| 3 | 88 | −4.00 (−7.56 to −0.44)d | 95 | −6.15 (−9.64 to −2.66)a | 183 | 2.15 (−2.84 to 7.13) | .40 | |

| 6 | 99 | −2.26 (−5.68 to 1.17) | 96 | −5.57 (−9.04 to −2.09)b | 195 | 3.31 (−1.57 to 8.19) | .18 | |

| 12 | 84 | −4.52 (−8.13 to −0.90)d | 86 | −5.51 (−9.12 to −1.91)b | 170 | 1.00 (−4.11 to 6.11) | .70 | |

| Satisfaction with pain medication | .73 | |||||||

| 3 | 88 | 1.46 (−2.93 to 5.86) | 92 | −0.34 (−4.73 to 4.05) | 180 | 1.81 (−4.41 to 8.02 | .57 | |

| 6 | 97 | −0.18 (−4.44 to 4.08) | 93 | 1.39 (−2.99 to 5.77) | 190 | −1.57 (−7.68 to 4.54) | .62 | |

| 12 | 83 | 0.77 (−3.72 to 5.25) | 84 | −0.34 (−4.87 to 4.19) | 167 | 1.11 (−5.27 to 7.48) | .73 | |

P < .001.

P < .01.

.05 < P < .10.

P < .05.

Secondary Outcomes

Table 3 and the eFigure in Supplement 2 detail outcomes for the intervention and control groups at 3, 6, and 12 months. For most outcomes, patients assigned to the n-of-1 group improved more or declined less than controls, but there were no statistically significant differences between the groups.

At the 6-month follow-up, more patients in the intervention group than control group reported that they had discussed starting or stopping treatment with a medication with the clinician who prescribed their pain treatments (57% [n = 62] vs 42% [n = 45]; P = .02). Among those so-reporting (n = 107), medication-related shared decision-making scores were higher among intervention patients than control patients (mean scale score, 79.6 vs 67.6; difference, 11.9; 95% CI, 2.6-21.2; P = .01). Results at 12 months were similar but not significant (74.8 vs 65.4; difference, 9.4; 95% CI, −0.15 to 19.0; P = .05).

Patients’ n-of-1 Trial Experiences

Among patients initiating an n-of-1 trial, 88% (n = 86) reported that they believed the Trialist app could help people like them manage their pain and 81% (n = 77) found it “extremely or very helpful” in keeping track of their pain (Table 1). Smaller majorities rated the app as helpful in working closely with their clinician, noticing things that made pain feel better, and having more confidence in the patient management approach going forward, while 49% (n = 46) found the app helpful in identifying pain triggers (Table 1). Results of the System Usability Scale suggested that the app was generally viewed as being easy to use (Table 1).

Sensitivity Analyses and Heterogeneity of Treatment Effects

Two sensitivity analyses were conducted. In the first, we performed a modified “as treated” analysis, reclassifying as controls the 10 patients assigned to the intervention group but who did not begin their n-of-1 trials. In the second, under the assumption that return of daily surveys would be correlated with adherence to the n-of-1 protocol, we assigned each patient in the intervention group a value between 0 and 100 to represent the percentage of daily outcome measurements they reported; control patients took on the value 0. Results of both sensitivity analyses were not materially different from those of the main analysis and are therefore not reported further. In addition, there were no more treatment-by-time-by-covariate interaction effects (P < .05) than would be expected by chance.

Safety

No trial-related adverse events were reported.

Discussion

This study addressed whether patients with CMSP who were randomized to an n-of-1 trial program would achieve better health outcomes and report better care experiences than those assigned to usual care. While patients in both groups improved from baseline with respect to the primary outcome of pain interference, there was no difference between the groups.

In this study, the primary outcome failed.39 However, 3 additional observations are pertinent. First, most findings favored n-of-1 participation. Second, more patients in the n-of-1 group than in the usual-care group achieved a 5-point improvement in pain interference, which represents a statistically significant change at the individual level.28 Third, medication-related shared decision making was better in the intervention group. There were more discussions about medication as well as higher-quality discussions. Enhanced patient engagement in care has been touted as a benefit of n-of-1 trials and may mediate effects on health.40 While none of these observations are by themselves practice changing, they do underscore the need for more research.

This study also adds important information about whether relatively unselected patients with chronic pain are willing to participate in and persist with n-of-1 trials. Most n-of-1 participants were diligent about providing daily symptom reports; patients found the mobile device app easy to use, and most patients found it helped them better manage their pain. Just 23% (n = 22) of completed n-of-1 trials statistically favored 1 treatment regimen over the other. However, even null n-of-1 trials could deliver useful information for decision making. While highlighting many challenges, our experience shows that n-of-1 trials are a potentially appealing vehicle for delivering precision medicine in office practice.41

Limitations

This evaluation incorporated a large n-of-1 series by historical standards,5 was conducted in diverse practices, used a strong randomized design, and emphasized patient-centered outcomes but was not without limitations. Patients were aware of the arm to which they were randomized; intervention patients received more attention than controls, and patients in the n-of-1 arm were aware of the pain-treatment regimens being compared. In the context of n-of-1 trials, lack of blinding is not always a limitation, depending on what one considers the active therapeutic ingredient. On the other hand, nearly all clinicians had patients in both arms, raising the prospect that clinicians might alter their communication style or medical decisions with 1 group based on experience with the other, biasing estimates toward the null. The study population was clinically heterogeneous. The number of study sites was limited, and all were from a single region. Although we received no clinician or patient reports of study-associated adverse events, the relatively small sample size and passive monitoring strategy may have missed n-of-1 trial–associated harms. Slow recruitment led to a 12% shortfall in anticipated enrollment and a 12-month (secondary) outcome missingness rate of 10%. Finally, even with mHealth support, n-of-1 trials place nontrivial demands on clinical practice, which may limit their uptake to enthusiasts.

Conclusions

In summary, clinicians and patients were willing to undertake mHealth-supported n-of-1 trials, but participation did not significantly improve the primary outcome of pain interference at 6 months. Nevertheless, n-of-1 trials may appeal to— and have value for—selected patients willing to join in clinician-guided self-experimentation. Additional research is needed to clarify which patients are most likely to benefit from participation in mHealth-supported n-of-1 trials and under what circumstances.

Trial Protocol.

eTable. Baseline characteristics for participants missing and not missing the primary outcome of pain interference at 3, 6, and 12 months follow-up.

eFigure. Comparison of intervention (N-of-1 trial) and control patients at 0, 3, 6, and 12 months from study entry.

References

- 1.Duan N, Kravitz RL, Schmid CH. Single-patient (n-of-1) trials: a pragmatic clinical decision methodology for patient-centered comparative effectiveness research. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(8)(suppl):S21-S28. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kravitz RL, Duan N, Braslow J. Evidence-based medicine, heterogeneity of treatment effects, and the trouble with averages. Milbank Q. 2004;82(4):661-687. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00327.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kent DM, Rothwell PM, Ioannidis JP, Altman DG, Hayward RA. Assessing and reporting heterogeneity in treatment effects in clinical trials: a proposal. Trials. 2010;11:85. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook DJ. Randomized trials in single subjects: the N of 1 study. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1996;32(3):363-367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gabler NB, Duan N, Vohra S, Kravitz RL. N-of-1 trials in the medical literature: a systematic review. Med Care. 2011;49(8):761-768. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318215d90d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaeschke R, Adachi J, Guyatt G, Keller J, Wong B. Clinical usefulness of amitriptyline in fibromyalgia: the results of 23 N-of-1 randomized controlled trials. J Rheumatol. 1991;18(3):447-451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li J, Gao W, Punja S, et al. Reporting quality of N-of-1 trials published between 1985 and 2013: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;76:57-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nikles CJ, Mitchell GK, Del Mar CB, Clavarino A, McNairn N. An n-of-1 trial service in clinical practice: testing the effectiveness of stimulants for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):2040-2046. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nikles CJ, Mitchell GK, Del Mar CB, McNairn N, Clavarino A. Long-term changes in management following n-of-1 trials of stimulants in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(11):985-989. doi: 10.1007/s00228-007-0361-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reitberg DP, Del Rio E, Weiss SL, Rebell G, Zaias N. Single-patient drug trial methodology for allergic rhinitis. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36(9):1366-1374. doi: 10.1345/aph.1C031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolfe B, Del Rio E, Weiss SL, et al. Validation of a single-patient drug trial methodology for personalized management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Manag Care Pharm. 2002;8(6):459-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zucker DR, Ruthazer R, Schmid CH, et al. Lessons learned combining N-of-1 trials to assess fibromyalgia therapies. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(10):2069-2077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kravitz RL, Duan N, Niedzinski EJ, Hay MC, Subramanian SK, Weisner TS. What ever happened to N-of-1 trials? Insiders’ perspectives and a look to the future. Milbank Q. 2008;86(4):533-555. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2008.00533.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langley P, Müller-Schwefe G, Nicolaou A, Liedgens H, Pergolizzi J, Varrassi G. The impact of pain on labor force participation, absenteeism and presenteeism in the European Union. J Med Econ. 2010;13(4):662-672. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2010.529379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rayner L, Hotopf M, Petkova H, Matcham F, Simpson A, McCracken LM. Depression in patients with chronic pain attending a specialised pain treatment centre: prevalence and impact on health care costs. Pain. 2016;157(7):1472-1479. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gureje O, Von Korff M, Simon GE, Gater R. Persistent pain and well-being: a World Health Organization study in primary care. JAMA. 1998;280(2):147-151. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, Hall K, Stein CM. Prescription of long-acting opioids and mortality in patients with chronic noncancer pain. JAMA. 2016;315(22):2415-2423. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-1645. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turk DC. The potential of treatment matching for subgroups of patients with chronic pain: lumping versus splitting. Clin J Pain. 2005;21(1):44-55. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200501000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clayman ML, Bylund CL, Chewning B, Makoul G. The impact of patient participation in health decisions within medical encounters: a systematic review. Med Decis Making. 2016;36(4):427-452. doi: 10.1177/0272989X15613530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henry SG, Bell RA, Fenton JJ, Kravitz RL. Goals of chronic pain management: do patients and primary care physicians agree and does it matter? Clin J Pain. 2017;33(11):955-961. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barr C, Marois M, Sim I, et al. The PREEMPT study—evaluating smartphone-assisted n-of-1 trials in patients with chronic pain: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:67. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0590-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krebs EE, Lorenz KA, Bair MJ, et al. Development and initial validation of the PEG, a three-item scale assessing pain intensity and interference. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(6):733-738. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0981-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun X, Ioannidis JP, Agoritsas T, Alba AC, Guyatt G. How to use a subgroup analysis: users’ guide to the medical literature. JAMA. 2014;311(4):405-411. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.285063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krebs EE, Gravely A, Nugent S, et al. Effect of opioid vs nonopioid medications on pain-related function in patients with chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain: the SPACE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(9):872-882. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kean J, Monahan PO, Kroenke K, et al. Comparative responsiveness of the PROMIS pain interference short forms, brief pain inventory, PEG, and SF-36 bodily pain subscale. Med Care. 2016;54(4):414-421. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amtmann D, Cook KF, Jensen MP, et al. Development of a PROMIS item bank to measure pain interference. Pain. 2010;150(1):173-182. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hays RD, Brodsky M, Johnston MF, Spritzer KL, Hui KK. Evaluating the statistical significance of health-related quality-of-life change in individual patients. Eval Health Prof. 2005;28(2):160-171. doi: 10.1177/0163278705275339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amtmann D, Kim J, Chung H, Askew RL, Park R, Cook KF. Minimally important differences for Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System pain interference for individuals with back pain. J Pain Res. 2016;9:251-255. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S93391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. ; PROMIS Cooperative Group . The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179-1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, Spritzer KL, Cella D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(7):873-880. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosser BA, McCracken LM, Velleman SC, Boichat C, Eccleston C. Concerns about medication and medication adherence in patients with chronic pain recruited from general practice. Pain. 2011;152(5):1201-1205. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.01.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thom DH, Ribisl KM, Stewart AL, Luke DA; Further validation and reliability testing of the Trust in Physician Scale. The Stanford Trust Study Physicians. Med Care. 1999;37(5):510-517. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199905000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evans CJ, Trudeau E, Mertzanis P, et al. Development and validation of the Pain Treatment Satisfaction Scale (PTSS): a patient satisfaction questionnaire for use in patients with chronic or acute pain. Pain. 2004;112(3):254-266. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems clinician and group surveys: supplemental items for adult surveys. Rockville, MD; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/surveys-guidance/item-sets/search.html. Accessed July 13, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hays RD, Berman LJ, Kanter MH, et al. Evaluating the psychometric properties of the CAHPS Patient-centered Medical Home survey. Clin Ther. 2014;36(5):689-696.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brooke J. SUS: A “quick and dirty” usability scale In: Jordan PW, Thomas BA, Weerdmeester I, McClelland IL, eds. Usability Evaluation in Industry. London: Taylor & Francis; 1996:189-194. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied Longitudinal Analysis. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pocock SJ, Stone GW. The primary outcome fails—what next? N Engl J Med. 2016;375(9):861-870. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1510064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaplan HC, Gabler NB. User Engagement, Training, and Support for Conducting N-of-1 Trials In: Kravitz RL, Duan N, eds. Design and Implementation of N-of-1 Trials: A User’s Guide. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Research and Quality; 2014:71-81. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kravitz RL. Personalized medicine without the “omics”. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(4):551. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2789-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol.

eTable. Baseline characteristics for participants missing and not missing the primary outcome of pain interference at 3, 6, and 12 months follow-up.

eFigure. Comparison of intervention (N-of-1 trial) and control patients at 0, 3, 6, and 12 months from study entry.