Key Points

Question

Can residential lead hazards be reduced to prevent childhood lead poisoning and associated neurobehavioral deficits?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 355 pregnant women and their children, a comprehensive residential intervention reduced dust lead loadings and, among non-Hispanic black children, blood lead concentrations but did not substantively improve neurobehavioral outcomes.

Meaning

Reducing residential lead exposures and, among those at higher risk of lead poisoning, blood lead concentrations is possible without elevating childhood body lead burden.

Abstract

Importance

Childhood lead exposure is associated with neurobehavioral deficits. The effect of a residential lead hazard intervention on blood lead concentrations and neurobehavioral development remains unknown.

Objective

To determine whether a comprehensive residential lead-exposure reduction intervention completed during pregnancy could decrease residential dust lead loadings, prevent elevated blood lead concentrations, and improve childhood neurobehavioral outcomes.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This longitudinal, community-based randomized clinical trial of pregnant women and their children, the Health Outcomes and Measures of the Environment (HOME) Study, was conducted between March 1, 2003, and January 31, 2006. Pregnant women attending 1 of 9 prenatal care clinics affiliated with 3 hospitals in the Cincinnati, Ohio, metropolitan area were recruited. Of the 1263 eligible women, 468 (37.0%) agreed to participate and 355 women (75.8%) were randomized in this intention-to-treat analysis. Participants were randomly assigned to receive 1 of 2 interventions designed to reduce residential lead or injury hazards. Follow-up on children took place at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 8 years of age. Data analysis was performed from September 2, 2017, to May 6, 2018.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Residential dust lead loadings were measured at baseline and when children were 1 and 2 years of age. At 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 8 years of age, the children’s blood lead concentrations as well as behavior, cognition, and executive functions were assessed.

Results

Of the 355 women randomized, 174 (49.0%) were assigned to the intervention group (mean [SD] age at delivery, 30.1 (5.5) years; 119 [68.3%] self-identified as non-Hispanic white) and 181 (50.9%) to the control group (mean [SD] age at delivery, 29.2 [5.7] years; 123 [67.9%] self-identified as non-Hispanic white). The intervention reduced the dust lead loadings for the floor (24%; 95% CI, –43% to 1%), windowsill (40%; 95% CI, –60% to –11%), and window trough (47%; 95% CI, –68% to –10%) surfaces. The intervention did not statistically significantly reduce childhood blood lead concentrations (–6%; 95% CI, –17% to 6%; P = .29). Neurobehavioral test scores were not statistically different between children in the intervention group than those in the control group except for a reduction in anxiety scores in the intervention group (β = –1.6; 95% CI, –3.2 to –0.1; P = .04).

Conclusions and Relevance

Residential lead exposures, as well as blood lead concentrations in non-Hispanic black children, were reduced through a comprehensive lead-hazard intervention without elevating the lead body burden. However, this decrease did not result in substantive neurobehavioral improvements in children.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00129324

This randomized clinical trial examines the potential neurobehavioral outcomes for children of lead-reduction efforts conducted in their home during their mothers’ pregnancy.

Introduction

Childhood blood lead concentrations, even those below the current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reference level of 5 μg/dL (to convert to micromoles per liter, multiply by 0.0483), are associated with cognitive impairments and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and with criminal arrests in adults.1,2,3,4 More than 3% of children in the United States have blood lead concentrations greater than 5 μg/dL.5 The burden of lead poisoning is disproportionately borne by non-Hispanic black children, who are more than twice as likely as non-Hispanic white children to have elevated blood lead concentrations.6,7 Despite dramatic reductions in blood lead levels from regulations that limit lead in gasoline, paint, and drinking water, many children continue to be exposed to residential lead hazards. More than 23 million US housing units, most of which were built before 1978, have at least 1 lead-based paint hazard.8,9 In addition, children may face lead exposure from water supply pipes and occupational take-home exposure from their parents.7

Effective interventions are needed to prevent childhood lead poisoning.2,3,10 Previous randomized clinical trials indicated that, with the exception of frequent professional cleaning, blood lead concentrations are not significantly reduced through simple interventions such as residential dust control.11 Moreover, home renovation activities that disturb lead paint (eg, dry sanding) may increase children’s lead exposure.12,13 A randomized clinical trial of young children with high blood lead concentrations (ie, 20-44 μg/dL) found that oral chelation therapy (dimercaptosuccinic acid) transiently reduced children’s blood lead concentrations but did not produce cognitive or behavioral benefits.14,15 To date, no randomized trials have tested the effect of a comprehensive, primary prevention intervention on residential lead exposures, blood lead concentrations, and neurobehavioral outcomes in children.

The purpose of this randomized clinical trial of pregnant women and their children (the Health Outcomes and Measures of the Environment [HOME] Study),16 was to test whether a comprehensive residential intervention could reduce lead exposures, prevent elevated childhood blood lead concentrations, and improve neurobehavioral outcomes in children, who were followed from delivery until 8 years of age.

Methods

The institutional review boards of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, participating hospitals and clinics, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention approved the HOME Study. During a face-to-face prenatal visit, prospective participants were informed about the trial by research assistants, who followed a checklist to ensure the study protocol was properly explained. Participating women provided written informed consent for themselves and their children. The trial protocol was registered on August 11, 2005 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00129324) and is available in Supplement 1. Data analysis was performed from September 2, 2017, to May 6, 2018.

Participant Recruitment and Intervention Assignment

Between March 1, 2003, and January 31, 2006, we recruited pregnant women into the HOME Study. We identified pregnant women who lived in the Cincinnati, Ohio, metropolitan area and attended 1 of 9 prenatal practices (University Obstetrics Clinic, University of Cincinnati Midwives, University of Cincinnati Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mercy Anderson Prenatal Clinical, Mt. Auburn Obstetrics and Gynecological Association, Dr Lum Practice, Walter T. Bowers, Good Samaritan Hospital Obstetrics Clinic, and Neighborhood Health Care) affiliated with 3 hospitals (University of Cincinnati Medical Center, Christ Hospital, and Mercy Anderson Hospital). Eligibility criteria included a mean (SD) gestation of 16 (3) weeks; 18 years of age or older; residence in a house built in or before 1978; not living in a mobile or trailer home; HIV-negative status; not taking medications for seizures or thyroid disorders; plan to continue prenatal care and to deliver at the participating clinics and hospitals; plan to live in the greater Cincinnati area for the next year; English fluency; and no diagnosis of diabetes, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or cancer that requires radiation treatment or chemotherapy. To target children at increased risk of lead exposure, we enrolled women living in homes built before 1978 and oversampled women who self-identified as non-Hispanic black (approximately 30%).6,7 We stratified enrollment so that approximately 50% (actual, 50%) of women were from urban, 30% (actual, 38%) from suburban, and 20% (actual, 12%) from rural areas.9

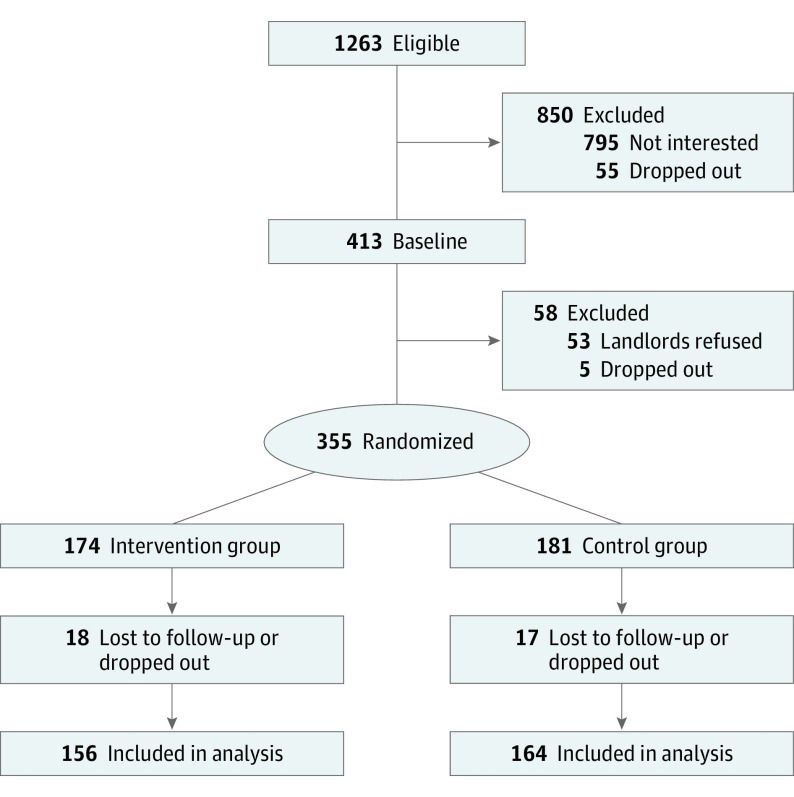

Of the 1263 eligible women, 468 (37.0%) agreed to participate (Figure 1). Sixty women (12.8%) dropped out during the run-in period, and 53 women (11.3%) were unable to participate because their landlords refused to participate. Using random number generation, we assigned the remaining 355 women (75.8%) in blocks of 10 to receive 1 of 2 interventions designed to reduce either residential lead hazards (intervention group [n = 174]) or injury hazards (control group [n = 181]) according to the home’s urban, suburban, or rural setting. We sealed the assignment codes in radio-opaque envelopes until the research assistants confirmed each participant’s eligibility.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of Participant Recruitment and Randomization .

Included in the analysis were participants who had at least 1 follow-up blood lead concentration measurement or neurobehavioral assessment at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 8 years of age.

Residential Intervention

By 32 weeks’ gestation and before delivery, the intervention group received a combination of interventions to reduce exposure to residential lead hazards. We identified the sources of exposure in the residences by quantifying the levels of lead in paint, dust, water, and soil samples with K-shell x-ray fluorescence and other previously described methods.17 These interventions included covering bare lead-contaminated soil with groundcover, installing a tap-water filter if the lead concentration in drinking water exceeded 2 μg/L, repairing and repainting peeling or deteriorating lead-based paint, creating smooth and cleanable floors and windows, installing window trough liners, replacing windows that have lead-based paint or show more than 10% deterioration, and undertaking extensive dust control and cleanup.

After these interventions were completed, we tested the floors, interior windowsills, and window troughs in the residences of the intervention group and, if necessary, ordered additional cleaning to ensure the dust lead loadings were less than 5 μg/sq ft for floors, 50 μg/sq ft for interior windowsills, and 400 μg/sq ft for window troughs, which were lower than the US regulatory standards at the time of under 40 μg/sq ft for floors, less than 250 μg/sq ft for interior windowsills, and less than 400 μg/sq ft for window troughs18,19 (to convert to square meter, multiply by 0.09). If a family moved before the child was 23 months of age, we attempted to implement the intervention in the new residence. Women assigned to the control group received injury prevention devices or residential modifications before their children were 6 months of age. Details of the injury hazard intervention were previously published.20

Dust Lead Measurements

We measured floor, interior windowsill, and window trough dust lead loadings before randomization (approximately 20 weeks’ gestation) and when the children were 1 and 2 years of age. We collected dust from floors, windowsills, and window troughs in the main activity room, child’s bedroom, and kitchen using wipes that were lot-tested for lead contamination. The 3 samples for each surface area were analyzed as a single composite. Floor dust was collected in a 1–sq ft area (to convert to square meter, multiply by 0.09); carpeted and noncarpeted surfaces were analyzed as separate composite samples, and the mean was calculated if both carpeted and noncarpeted surfaces were present. Dust samples from windowsills were taken before samples from window troughs. A rectangular area of the windowsill and the window trough was marked with tape and measured before sampling using a wipe. We attempted to take samples from the same floor area or window at each visit. After collection, lead loadings were quantified using flame atomic absorption spectrometry or graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry.

Blood Lead Concentrations

We collected whole blood from women at 16 and 26 weeks’ gestation and shortly before or within 48 hours of delivery as well as from children at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 8 years of age. We used collection materials prescreened for lead contamination. Blood samples were stored at –80°C until they were shipped on dry ice to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention laboratories for analysis. Blood lead concentrations were quantified using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry.21 All batches included reagent blanks and quality control samples (coefficient of variation, <3.5%).

Neurobehavioral Outcomes

We serially assessed children’s neurobehavior from 1 to 8 years of age (eTable 1 and eMethods in Supplement 2).22 We administered the Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition, a parent-reported questionnaire, to assess behavioral problems at 2, 3, 4, 5, and 8 years of age.23 We used the Bayley Scales of Infant Development, Second Edition, to assess children’s mental (cognition and language) and psychomotor (gross and fine motor) development at 1, 2, and 3 years of age.24 Parents completed the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function, a parent-reported measure of their children’s executive functions at 3, 4, 5, and 8 years of age. We assessed 2 additional executive function domains, inattention and impulsivity, by administering the Conners’ Continuous Performance Test at 5 and 8 years of age. Finally, to evaluate children’s cognitive abilities, we administered the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, Third Edition, at 5 years of age and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition, at 8 years of age.25,26

Higher scores in Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition; Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function; and Conners’ Continuous Performance Test indicate worse behaviors, whereas higher scores in Bayley Scales of Infant Development, Second Edition; Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, Third Edition; and Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition indicate better performance. One of us (K.Y.) was trained to validly and reliably administer these instruments.

Baseline Factors

We assessed maternal sociodemographic factors using standardized interviews and abstracted data on infant sex, birth weight, and gestational age from medical records. We measured maternal IQ using the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (mean [SD] score, 100 [15], with higher scores indicating better performance).27

Sample Size Calculation

We estimated that we had 80% power to detect a 3.4-point difference in IQ with 180 children per group using previously published associations between blood lead concentrations and IQ1 and assuming a 3.4-μg/dL difference in blood lead concentrations (ie, approximately 40%) between the intervention and control groups.

Statistical Analysis

In this intention-to-treat analysis, we used χ2 and unpaired, 2-tailed t tests to compare baseline sociodemographic characteristics, blood lead concentrations, and baseline dust lead loadings between intervention and control groups. We used a linear mixed model with a 5-knot restricted cubic polynomial spline for child age to examine blood lead concentration trajectories from 1 to 8 years of age by intervention status because concentrations increased from 1 to 2 years of age and then decreased. We used linear regression with generalized estimating equations to estimate the differences between intervention and control groups in repeated dust lead loadings (ln-transformed), childhood blood lead concentrations (ln-transformed), and neurobehavioral test scores. To account for age-associated changes in concentrations, we adjusted the concentration models for child age at testing. We also estimated the relative risk of having elevated blood lead concentrations (>2.5 μg/dL or >5 μg/dL) at any follow-up visit using modified Poisson regression.28 All statistical analyses were conducted with SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Because of the racial disparities in lead exposure,6,7 we conducted secondary analyses stratified by maternal race/ethnicity. We evaluated whether intervention effects differed by maternal race/ethnicity (denoted as child race/ethnicity) using product interaction terms between intervention status and race/ethnicity. We did not examine women who self-identified their race/ethnicity as “other” because of the small sample size and heterogeneous nature of this category. We conducted a per protocol analysis including families who lived at their baseline residence until the child turned 3 years of age. We also adjusted our blood lead models for baseline dust lead loadings. Finally, we estimated the sampling and intervention effects on dust lead loadings (eAppendix in Supplement 2).

Results

Randomization and Retention

Of the 355 women randomized, 174 (49.0%) were assigned to the intervention group and 181 (50.9%) to the control group. Of the women in the intervention group, 119 (68.3%) self-identified as non-Hispanic white and 44 (25.3%) as non-Hispanic black with a mean (SD) age at delivery of 30.1 (5.5) years. Of the women in the control group, 123 (67.9%) self-identified as non-Hispanic white and 45 (24.8%) as non-Hispanic black with a mean (SD) age at delivery of 29.2 (5.7) years. Children were predominantly non-Hispanic white (242 [68.2%]) and male (166 [46.8%]). Baseline participant characteristics did not significantly differ between the intervention and control groups (Table).

Table. Continuous and Categorical Covariates at Baseline for Intervention and Control Groupsa.

| Covariate | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention Group (n = 174) | Control Group (n = 181) | |

| Maternal race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 119 (68.3) | 123 (67.9) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 44 (25.3) | 45 (24.8) |

| Other | 11 (6.3) | 13 (7.1) |

| Marital status (married or living as married) | 124 (71.2) | 128 (70.7) |

| Maternal educational level | ||

| ≤High school diploma | 36 (20.7) | 31 (17.1) |

| Some college | 37 (21.3) | 52 (28.7) |

| Bachelor’s/graduate degree | 101 (58.0) | 98 (54.1) |

| Maternal residence area | ||

| Urban | 104 (59.8) | 102 (56.3) |

| Suburban | 69 (39.7) | 67 (37.0) |

| Rural | 8 (4.6) | 5 (2.7) |

| Maternal age at delivery, y | ||

| No. | 166 | 177 |

| Mean (SD) | 30.1 (5.5) | 29.2 (5.7) |

| Maternal depression symptoms (BDI) | ||

| No. | 174 | 180 |

| Mean (SD) | 9.1 (6.8) | 9.7 (7.0) |

| Household income, thousands, US $ | ||

| No. | 173 | 178 |

| Mean (SD) | 67 (44) | 60 (41) |

| GM pregnancy blood lead, μg/dL | ||

| No. | 167 | 171 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.7 (1.5) | 0.7 (1.5) |

| GM baseline floor dust lead loading, μg/sq ft | ||

| No. | 169 | 181 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.5 (4.8) | 1.9 (4.9) |

| GM baseline windowsill dust lead loading, μg/sq ft | ||

| No. | 169 | 181 |

| Mean (SD) | 28 (8.5) | 33 (9.7) |

| GM baseline window trough dust lead loading, μg/sq ft | ||

| No. | 166 | 177 |

| Mean (SD) | 574 (14) | 510 (17) |

| Maternal full-scale IQ (WASI) | ||

| No. | 146/155 | |

| Mean (SD) | 108 (15) | 109 (13) |

| Child sex, male, No. (%) | 89 (51.1) | 77 (42.5) |

| Infant birth weight, kg | ||

| No. | 166 | 177 |

| Mean (SD) | 3.4 (5.9) | 3.3 (6.3) |

| Infant gestational age at delivery, wk | ||

| No. | 166 | 177 |

| Mean (SD) | 39.0 (1.5) | 39.0 (2.0) |

Abbreviations: BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; GM, geometric mean; WASI, Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (mean [SD] score, 100 [15], with higher scores indicating better performance). SI conversion factors: To convert blood lead level to micromoles per liter, multiply by 0.0483; dust lead loading to square meter, multiply by 0.09.

P > .05 for all differences between intervention and control groups.

Baseline dust lead loadings for floor (mean [SD], 1.5 [4.8] μg/sq ft vs 1.9 [4.9] μg/sq ft), windowsill (mean [SD], 28 [8.5] μg/sq ft vs 33 [9.7] μg/sq ft), and window trough (mean [SD], 574 [14] μg/sq ft vs 510 [17] μg/sq ft) were not significantly different between the intervention and control groups (all P > .20; Table). A total of 315 children (intervention: 155; control: 160) completed at least 1 follow-up visit; 297 children (94.3%; intervention: 144; control: 153) were aged 1 year, 267 (84.8%; intervention: 133; control: 134) aged 2 years, 247 (78.4%; intervention: 121; control: 126) aged 3 years, 170 (53.9%; intervention: 80; control: 90) aged 4 years, 186 (59.0%; intervention: 89; control: 97) aged 5 years, and 199 (63.2%; intervention: 98; control: 101) aged 8 years. We did not identify any adverse events associated with the intervention. In the control group, 1 child sustained a head injury from a stair gate we installed and another child had a blood lead concentration of 28 μg/dL.

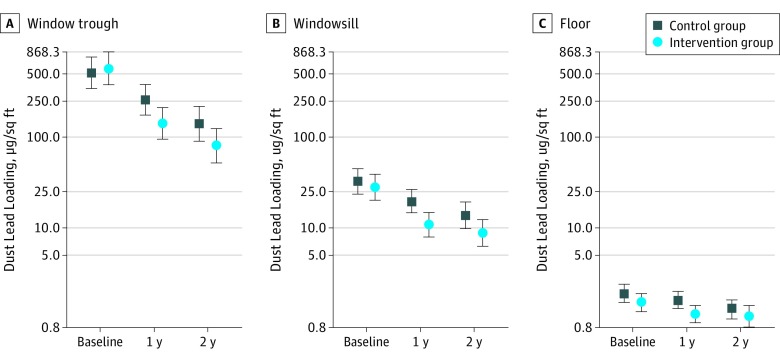

Dust Lead Loadings

Dust lead loadings at 1 and 2 years of age were lower in the intervention group than the control group (Figure 2; eTable 2 in Supplement 2). Floor (−24%; 95% CI, –43 to 1), windowsill (−40%; 95% CI, –60 to –11), and window trough (−47%; 95% CI, –68 to –10) dust lead loadings were lower in residences of the intervention group compared with residences of the control group. Geometric mean dust lead loadings did not rise between 1 and 2 years of age in either the intervention or control group. Reductions in floor dust lead loadings caused by the intervention were greater in the residences of non-Hispanic blacks than of non-Hispanic whites (intervention × race/ethnicity P = .09), but windowsill or window trough dust lead loading reductions were not (intervention × race/ethnicity P > .20) (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Figure 2. Geometric Mean Dust Lead Loading on Window Trough, Windowsill, and Floor at Baseline and at Child Ages 1 and 2 Years.

Error bars represent the 95% CI of the geometric mean. There were 350 children at baseline, and 314 children (559 repeats) at 1 and 2 years of age. To convert dust lead loading to square meter, multiply by 0.09.

Blood Lead Concentrations

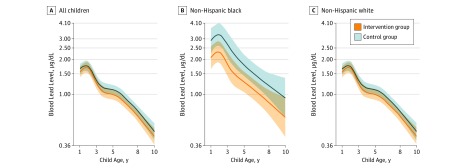

Blood lead concentrations from 1 to 8 years of age were not significantly lower among children in the intervention group compared with children in the control group (–6%; 95% CI, –17 to 6; P = .29) (Figure 3; eTable 3 in Supplement 2). However, race/ethnicity modified the intervention effect (intervention × race/ethnicity P = .03). Among non-Hispanic black children, blood lead concentrations were 31% lower (95% CI, –50 to –5; P = .02) among the intervention group than the control group. In contrast, the effect of the intervention was null among non-Hispanic white children (–2%; 95% CI, –14 to 12; P = .79). Children in the intervention group had no substantial decrease in risk of having blood lead concentrations greater than 2.5 μg/dL or 5 μg/dL at 1 to 8 years of age (eTable 4 in Supplement 2). The effect of preventing blood lead concentrations greater than 2.5 μg/dL was stronger among non-Hispanic black children (relative risk [RR], 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4-1.0) than among non-Hispanic white children (RR, 1.0; 95% CI, 0.5-1.9; race/ethnicity × intervention P = .06). Few children (4 in the control group and 2 in the intervention group) had blood lead concentrations greater than 10 μg/dL (RR, 0.05; 95% CI, 0.08-3.50).

Figure 3. Geometric Mean Childhood Blood Lead Concentrations Between 1 and 8 Years of Age Stratified by Race/Ethnicity .

Blood lead concentrations were measured in venous whole-blood samples collected from children at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 8 years of age. There were 315 total children (1165 repeated measures), 226 children born to non-Hispanic white women (843 repeats), and 69 children born to non-Hispanic black women (255 repeats). No significant differences were found in blood lead concentrations across the intervention and control arms among all children (P = .20). Among children of non-Hispanic black women, levels were significantly lower in the intervention group than in the control group (P = .02), but no significant differences were found in the children of non-Hispanic white women (P = .29; intervention × race/ethnicity P = .03). Age-specific geometric mean blood lead concentrations were derived from a mixed model that included intervention arm, a 5-knot restricted cubic polynomial spline for age, and intervention × age interaction terms. Shading indicates 95% CIs. Blood lead level is reported in micrograms per deciliter (to convert to micromoles per liter, multiply by 0.0483).

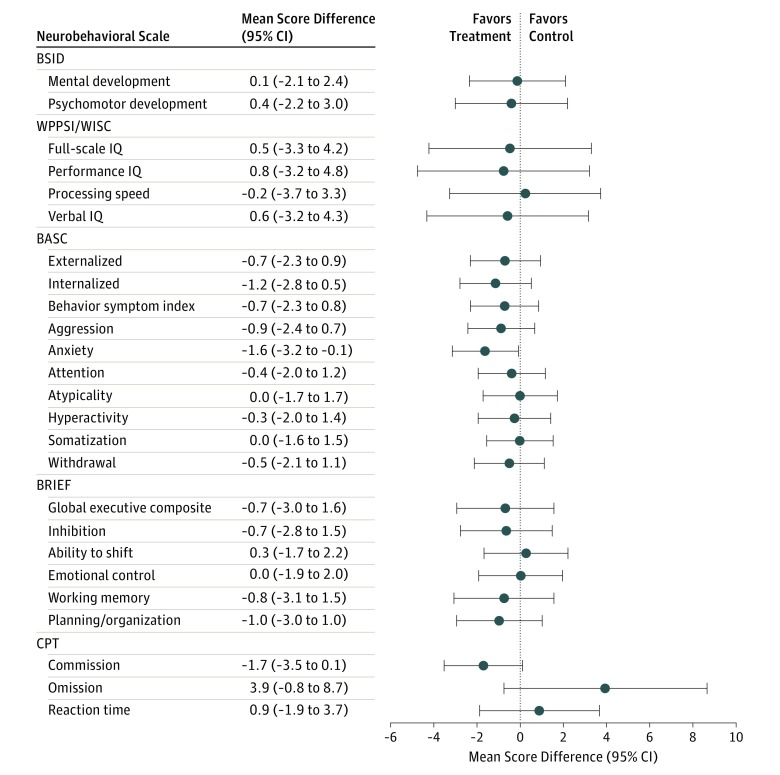

Neurobehavioral Outcomes

In general, children in the intervention group had statistically insignificant slightly lower behavioral problem scores, higher IQ scores, and better executive function than children in the control group; most average differences in neurobehavioral scores were less than 1 point, with some exceptions. (Figure 4; eTable 5 in Supplement 2). Notably, children in the intervention group had less parent-reported anxiety than children in the control group (β = –1.6; 95% CI, –3.2 to –0.1; P = .04). We observed little evidence that race/ethnicity modified the intervention effect on neurobehavior (eTable 5 in Supplement 2). However, the intervention effect on verbal IQ scores appeared beneficial among non-Hispanic white children (difference: 4.2; 95% CI, 0.2-8.2) but not among non-Hispanic black children (difference: −6.8; 95% CI, −14 to 0.3) (intervention × race/ethnicity P < .01).

Figure 4. Mean Differences in Neurobehavioral Test Scores at 1 to 8 Years of Age.

Score differences and robust 95% CIs were derived from a linear regression with generalized estimating equations that account for the repeated outcome measures. BASC indicates Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition (scores at 2, 3, 4, 5, and 8 years of age; n = 290; 1051 repeats); BRIEF, Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (scores at 3, 4, 5, and 8 years of age; n = 270; 777 repeats); BSID, Bayley Scales of Infant Development, Second Edition (scores at 1, 2, and 3 years of age; n = 302; 783 repeats); CPT, Conners’ Continuous Performance Test (scores at 5 and 8 years of age; n = 215; 316 repeats); WPPSI/WISC, Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, Third Edition/Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition (IQ scores at 5 and 8 years of age; n = 225; 374 repeats). A negative coefficient on the BSID, WPPSI, and WISC scales indicates that children in the treatment group had higher (ie, better) scores than children in the control group. The mean (SD) score in the normalization sample for BSID was 100 (15); BASC, 50 (10); WPPSI/WISC, 100 (15); BRIEF, 50 (10); and CPT, 50 (10).

In our per protocol analysis, 295 families (83.1%) remained in the same residence until the children were 3 years of age, and we observed stronger and statistically significant effects of the intervention on dust lead loadings (29%-60% decrease) and blood lead concentrations (–14%; 95% CI, –24 to –2; eTables 6 and 7 in Supplement 2). The effect of the intervention on neurobehavior was unchanged (eTable 8 in Supplement 2). The pattern of results was not meaningfully changed when we adjusted for baseline dust lead loadings (eTable 9 in Supplement 2). Between the baseline visit and visits at 1 and 2 years of age, the intervention caused significant decreases in windowsill and window trough dust lead loadings but not in floor dust lead loadings (eTable 10 in Supplement 2).

Discussion

We conducted a randomized clinical trial to determine whether reducing residential lead hazards could prevent elevated blood lead concentrations and lead-associated neurobehavioral deficits in children with low-level lead exposures typical in many children who live in urban areas in the United States.29 The intervention we implemented reduced residential dust lead loadings and caused small but statistically nonsignificant reductions in childhood blood lead concentrations; these reductions were substantially greater among non-Hispanic black children, who were more heavily exposed, than non-Hispanic white children. Neurobehavioral outcomes were generally better among children in the intervention group than those in the control group, but the effects were modest and most were not statistically significant. Only anxiety scores, which were previously associated with higher blood lead concentrations,30 were significantly lower among children in the intervention group.

The intervention reduced residential dust lead contamination, historically one of the most important sources of childhood lead exposure, over the children’s first 2 years of life.31,32 Previous studies showed that lead-contaminated house dust, even at levels below the US Environmental Protection Agency standards, was associated with increased blood lead concentrations.32,33 Improper residential renovation and repair may increase childhood blood lead concentrations,12,13 but this intervention was able to achieve floor dust lead loadings below 5 μg/sq ft, window sill lead loadings below 50 μg/sq ft, and window trough dust lead loadings below 400 μg/sq ft as well as reduce dust lead loadings for at least 2 years without increasing the children’s blood lead concentrations. Thus, effectively reducing residential lead hazards is possible without elevating lead exposure.

One reason that this intervention did not substantially reduce blood lead concentrations in all children may be the relatively low-level lead exposure in this cohort. This hypothesis is supported by our secondary analysis examining racial/ethnic subgroups. The intervention substantially lowered blood lead concentrations of non-Hispanic black children, who lived in homes with higher baseline residential dust lead loadings, had higher blood lead concentrations, and had greater intervention-induced decreases in floor dust lead loadings, compared with non-Hispanic white children. Thus, the intervention may have been insufficient to meaningfully reduce childhood blood lead concentrations when residential lead exposures were low but other sources of exposure (eg, other homes, diet) were present.7 In addition, the intervention may have had a greater effect on non-Hispanic black children who may absorb lead more efficiently than non-Hispanic white children do, as lead mimics calcium.31,34

The intervention’s lack of a protective effect on children’s neurobehavior is likely the result of modest reductions in blood lead concentrations accompanying the intervention, which were insufficient to substantially improve neurobehavioral function. However, given the well-documented adverse effects of lead on children’s neurodevelopment, even at low levels, efforts to prevent and minimize lead exposure are still necessary.1,2,3 Race/ethnicity modified the effect of the intervention on verbal IQ scores, but we did not observe consistent evidence that race/ethnicity modified the effect on neurobehavioral outcomes, despite larger decreases in blood lead concentrations among non-Hispanic black children.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of the HOME Study was the longitudinal follow-up, which allowed us to determine that the intervention’s effects on blood lead concentrations and neurobehavior were stable over the first 8 years of a child’s life. In addition, the study enabled us to assess multiple domains of children’s neurobehavior, including many domains that were previously associated with lead exposure.35

This study had several limitations. First, we did not implement the intervention among children with higher residential lead exposure who likely have greater lead-associated neurobehavioral decrements. Second, because of the modest number of non-Hispanic blacks in the study, we could not precisely estimate the intervention effect on this group. Third, we did not try to reduce nonresidential sources of lead exposure, which would have been difficult given the myriad sources. Fourth, baseline factors were equally distributed between the intervention and control groups, but we cannot exclude the possibility that unmeasured factors (eg, maternal bone lead concentrations) varied across the 2 arms.36 Finally, it is possible that the anxiety results are spurious as we made numerous comparisons.

These findings should be generalizable to children living in pre-1978 residences in other Midwestern cities, given that blood lead concentrations of study participants are similar to levels of children in the United States during the study period.37 However, this intervention may be more effective among high-risk populations, such as non-Hispanic black communities in older housing.

Conclusions

The results of this study appear to demonstrate that low-level lead exposure can be prevented. The comprehensive primary prevention intervention provided to participants significantly reduced dust lead levels and, among heavily exposed children, blood lead concentrations. In addition, we found that much lower dust lead levels than previously believed possible can be achieved. This finding offers clinicians and public health practitioners with an opportunity to prevent childhood lead exposure and is directly relevant to a recent court order38 mandating the US Environmental Protection Agency to promulgate a lower residential dust lead standard. Finally, minimizing lead exposure may not be sufficient to prevent lead-associated neurobehavioral deficits, and eliminating residential lead exposures may be necessary to prevent adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Trial Protocol

eMethods. Description of Neurobehavioral Test Administration in the HOME Study

eTable 1. Description of Neurobehavioral Tests Administered to Children or Parents from Ages 1 to 8 Years Among HOME Study Participants

eTable 2. Geometric Mean (GM) Dust Lead Loadings (μg/ft2) on Floors, Windowsills, and Window Troughs at Baseline and Child Age 1 and 2 Years According to Residential Lead Hazard Reduction Intervention Among All Children and Stratified by Maternal Race (The HOME Study; Cincinnati, OH)a,b,c,d

eTable 3. Geometric Mean Blood Lead Concentrations (μg/dL) From Age 1 to 8 Years of Age According to Residential Lead Hazard Reduction Intervention Among All Children and Stratified by Maternal Race (The HOME Study; Cincinnati, OH)

eTable 4. Relative Risk of Having Blood Lead Concentrations >2.5 μg/dL or >5 μg/dL From Ages 1 to 8 Years of Age According to Residential Lead Hazard Reduction Intervention Among All Children and Stratified by Maternal Race (The HOME Study; Cincinnati, OH)

eTable 5. Difference in Neurobehavioral Test Scores From Age 1 to 8 Years of Age According to In-Home Lead Hazard Reduction Intervention Among All Children and Stratified by Maternal Race (The HOME Study; Cincinnati, OH)a

eTable 6. Percent Difference in Dust Lead Loadings (μg/ft2) on Floor, Windowsill, and Window Trough Surfaces According to In-Home Lead Hazard Reduction Intervention at Child Ages 1 and 2 Years: Per-Protocol Analysis (The HOME Study; Cincinnati, OH)a,b

eTable 7. Percent Difference in Childhood Blood Lead Concentrations From Age 1-8 Years According to In-Home Lead Hazard Reduction Intervention Among All Children and Stratified by Maternal Race: Per-Protocol Analysis (The HOME Study; Cincinnati, OH)a,b,c

eTable 8. Difference in Neurobehavioral Test Scores From Age 1 to 8 Years of Age According to In-Home Lead Hazard Reduction Intervention Among All Children and Stratified by Maternal Race: Per-Protocol Analysis (The HOME Study; Cincinnati, OH).a,b

eTable 9. Adjusted Percent Differences in Blood Lead Concentrations (μg/dL) From Age 1 to 8 Years of Age According to Residential Lead Hazard Reduction Intervention Among All Children and Stratified by Maternal Race (The HOME Study; Cincinnati, OH)

eTable 10. Percent Change in Dust Lead Loadings Due to Intervention Effect After Accounting for Sampling Effect (The HOME Study; Cincinnati, OH)

eAppendix. Sampling and Intervention Effects on Household Dust Lead Loadings

References

- 1.Lanphear BP, Hornung R, Khoury J, et al. . Low-level environmental lead exposure and children’s intellectual function: an international pooled analysis. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(7):894-899. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braun JM, Kahn RS, Froehlich T, Auinger P, Lanphear BP. Exposures to environmental toxicants and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in U.S. children. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(12):1904-1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright JP, Dietrich KN, Ris MD, et al. . Association of prenatal and childhood blood lead concentrations with criminal arrests in early adulthood. PLoS Med. 2008;5(5):e101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Toxicology Program. NTP Monograph: Health Effects of Low-Level Lead. US Department of Health and Human Services. https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/ohat/lead/final/monographhealtheffectslowlevellead_newissn_508.pdf. Published June 2012. Accessed November 1, 2017.

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC’s national surveillance data (1997-2015). https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/data/national.htm. Accessed October 6, 2017.

- 6.Raymond J, Wheeler W, Brown MJ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Lead screening and prevalence of blood lead levels in children aged 1-2 years–Child Blood Lead Surveillance System, United States, 2002-2010 and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 1999-2010. MMWR Suppl. 2014;63(2):36-42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levin R, Brown MJ, Kashtock ME, et al. . Lead exposures in U.S. children, 2008: implications for prevention. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(10):1285-1293. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Department of Housing and Urban Development; American Health Homes Survey. Washington, DC: US Department of Housing and Urban Development. Office of Healthy Homes and Lead Hazard Control; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs DE, Clickner RP, Zhou JY, et al. . The prevalence of lead-based paint hazards in U.S. housing. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(10):A599-A606. doi: 10.1289/ehp.021100599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazumdar M, Bellinger DC, Gregas M, Abanilla K, Bacic J, Needleman HL. Low-level environmental lead exposure in childhood and adult intellectual function: a follow-up study. Environ Health. 2011;10(1):24-30. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-10-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haynes E, Lanphear BP, Tohn E, Farr N, Rhoads GG. The effect of interior lead hazard controls on children’s blood lead concentrations: a systematic evaluation. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(1):103-107. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spanier AJ, Wilson S, Ho M, Hornung R, Lanphear BP. The contribution of housing renovation to children’s blood lead levels: a cohort study. Environ Health. 2013;12:72-79. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-12-72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reissman DB, Matte TD, Gurnitz KL, Kaufmann RB, Leighton J. Is home renovation or repair a risk factor for exposure to lead among children residing in New York City? J Urban Health. 2002;79(4):502-511. doi: 10.1093/jurban/79.4.502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogan WJ, Dietrich KN, Ware JH, et al. ; Treatment of Lead-Exposed Children Trial Group . The effect of chelation therapy with succimer on neuropsychological development in children exposed to lead. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(19):1421-1426. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105103441902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dietrich KN, Ware JH, Salganik M, et al. ; Treatment of Lead-Exposed Children Clinical Trial Group . Effect of chelation therapy on the neuropsychological and behavioral development of lead-exposed children after school entry. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):19-26. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braun JM, Kalloo G, Chen A, et al. . Cohort profile: the Health Outcomes and Measures of the Environment (HOME) study. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(1):24-33. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Department of Housing and Urban Development. Evaluation and Control of Lead-Based Paint Hazards in Housing. Washington, DC: US Department of Housing and Urban Development; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Environmental Protection Agency. Lead; identification of dangerous levels of lead; final rule. 40 CFR Part 745, §66. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2001-01-05/pdf/01-84.pdf. Published January 5, 2001. Accessed November 1, 2017.

- 19.US Department of Housing and Urban Development; Revised dust-lead action levels for risk assessment and clearance; clearance of porch floors. Policy Guidance Number 2017-01. https://www.hud.gov/sites/documents/PMS17_PGI-2017-01REV1.PDF. Published February 16, 2017. Accessed November 1, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phelan KJ, Khoury J, Xu Y, Liddy S, Hornung R, Lanphear BP. A randomized controlled trial of home injury hazard reduction: the HOME injury study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(4):339-345. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones DR, Jarrett JM, Tevis DS, et al. . Analysis of whole human blood for Pb, Cd, Hg, Se, and Mn by ICP-DRC-MS for biomonitoring and acute exposures. Talanta. 2017;162:114-122. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2016.09.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dietrich KN, Eskenazi B, Schantz S, et al. . Principles and practices of neurodevelopmental assessment in children: lessons learned from the Centers for Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(10):1437-1446. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW. Behavior Assessment System for Children. Bloomington, MN: Pearson; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development. 2nd ed San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wechsler D. Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence. 3rd ed San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-IV. 3rd ed San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702-706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsoi MF, Cheung CL, Cheung TT, Cheung BM. Continual decrease in blood lead level in Americans: United States National Health Nutrition and Examination Survey 1999-2014. Am J Med. 2016;129(11):1213-1218. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.05.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu J, Liu X, Wang W, et al. . Blood lead concentrations and children’s behavioral and emotional problems: a cohort study. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(8):737-745. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lanphear BP, Hornung R, Ho M, Howard CR, Eberly S, Knauf K. Environmental lead exposure during early childhood[published correction appears in J Pediatr. 2002;140(4):4–70.]. J Pediatr. 2002;140(1): 40-47. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.120513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lanphear BP, Matte TD, Rogers J, et al. . The contribution of lead-contaminated house dust and residential soil to children’s blood lead levels. A pooled analysis of 12 epidemiologic studies. Environ Res. 1998;79(1):51-68. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1998.3859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dixon SL, Gaitens JM, Jacobs DE, et al. . Exposure of U.S. children to residential dust lead, 1999-2004: II. The contribution of lead-contaminated dust to children’s blood lead levels. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(3):468-474. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haynes EN, Kalkwarf HJ, Hornung R, Wenstrup R, Dietrich K, Lanphear BP. Vitamin D receptor Fok1 polymorphism and blood lead concentration in children. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111(13):1665-1669. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bellinger DC. Very low lead exposures and children’s neurodevelopment. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20(2):172-177. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3282f4f97b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Téllez-Rojo MM, Hernández-Avila M, Lamadrid-Figueroa H, et al. . Impact of bone lead and bone resorption on plasma and whole blood lead levels during pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(7):668-678. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Blood lead levels in children aged 1-5 years - United States, 1999-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(13):245-248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Review of the dust-lead hazard standards and the definition of lead based paint. Fed Regist. 2018;83(127):30889-30901. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eMethods. Description of Neurobehavioral Test Administration in the HOME Study

eTable 1. Description of Neurobehavioral Tests Administered to Children or Parents from Ages 1 to 8 Years Among HOME Study Participants

eTable 2. Geometric Mean (GM) Dust Lead Loadings (μg/ft2) on Floors, Windowsills, and Window Troughs at Baseline and Child Age 1 and 2 Years According to Residential Lead Hazard Reduction Intervention Among All Children and Stratified by Maternal Race (The HOME Study; Cincinnati, OH)a,b,c,d

eTable 3. Geometric Mean Blood Lead Concentrations (μg/dL) From Age 1 to 8 Years of Age According to Residential Lead Hazard Reduction Intervention Among All Children and Stratified by Maternal Race (The HOME Study; Cincinnati, OH)

eTable 4. Relative Risk of Having Blood Lead Concentrations >2.5 μg/dL or >5 μg/dL From Ages 1 to 8 Years of Age According to Residential Lead Hazard Reduction Intervention Among All Children and Stratified by Maternal Race (The HOME Study; Cincinnati, OH)

eTable 5. Difference in Neurobehavioral Test Scores From Age 1 to 8 Years of Age According to In-Home Lead Hazard Reduction Intervention Among All Children and Stratified by Maternal Race (The HOME Study; Cincinnati, OH)a

eTable 6. Percent Difference in Dust Lead Loadings (μg/ft2) on Floor, Windowsill, and Window Trough Surfaces According to In-Home Lead Hazard Reduction Intervention at Child Ages 1 and 2 Years: Per-Protocol Analysis (The HOME Study; Cincinnati, OH)a,b

eTable 7. Percent Difference in Childhood Blood Lead Concentrations From Age 1-8 Years According to In-Home Lead Hazard Reduction Intervention Among All Children and Stratified by Maternal Race: Per-Protocol Analysis (The HOME Study; Cincinnati, OH)a,b,c

eTable 8. Difference in Neurobehavioral Test Scores From Age 1 to 8 Years of Age According to In-Home Lead Hazard Reduction Intervention Among All Children and Stratified by Maternal Race: Per-Protocol Analysis (The HOME Study; Cincinnati, OH).a,b

eTable 9. Adjusted Percent Differences in Blood Lead Concentrations (μg/dL) From Age 1 to 8 Years of Age According to Residential Lead Hazard Reduction Intervention Among All Children and Stratified by Maternal Race (The HOME Study; Cincinnati, OH)

eTable 10. Percent Change in Dust Lead Loadings Due to Intervention Effect After Accounting for Sampling Effect (The HOME Study; Cincinnati, OH)

eAppendix. Sampling and Intervention Effects on Household Dust Lead Loadings