This randomized clinical trial compares treatment with everolimus plus exemestane vs everolimus or capecitabine monotherapy for estrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer.

Key Points

Question

What is the estimated clinical benefit of everolimus plus exemestane vs everolimus or capecitabine monotherapies for endocrine therapy–resistant, estrogen receptor–positive advanced breast cancer?

Findings

This randomized clinical trial of 309 patients found a progression-free survival (PFS) benefit for everolimus plus exemestane over everolimus alone and a numerical PFS difference favoring capecitabine over combination therapy (note that imbalances among baseline parameters and potential informative censoring might have contributed to the PFS outcomes observed with capecitabine). No new safety signals were observed with the combination regimen.

Meaning

Everolimus plus exemestane combination therapy offers an efficacy benefit vs everolimus alone, but the efficacy difference between combination therapy and capecitabine alone is still uncertain.

Abstract

Importance

Everolimus plus exemestane and capecitabine are approved second-line therapies for advanced breast cancer.

Objective

A postapproval commitment to health authorities to estimate the clinical benefit of everolimus plus exemestane vs everolimus or capecitabine monotherapy for estrogen receptor–positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative advanced breast cancer.

Design

Open-label, randomized, phase 2 trial of treatment effects in postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer that had progressed during treatment with nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitors.

Interventions

Patients were randomized to 3 treatment regimens: (1) everolimus (10 mg/d) plus exemestane (25 mg/d); (2) everolimus alone (10 mg/d); and (3) capecitabine alone (1250 mg/m2 twice daily).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Estimated hazard ratios (HRs) of progression-free survival (PFS) for everolimus plus exemestane vs everolimus alone (primary objective) or capecitabine alone (key secondary objective). Safety was a secondary objective. No formal statistical comparisons were planned.

Results

A total of 309 postmenopausal women were enrolled, median age, 61 years (range, 32-88 years). Of these, 104 received everolimus plus exemestane; 103, everolimus alone; and 102, capecitabine alone. Median follow-up from randomization to the analysis cutoff (June 1, 2017) was 37.6 months. Estimated HR of PFS was 0.74 (90% CI, 0.57-0.97) for the primary objective of everolimus plus exemestane vs everolimus alone and 1.26 (90% CI, 0.96-1.66) for everolimus plus exemestane vs capecitabine alone. Between treatment arms, potential informative censoring was noted, and a stratified multivariate Cox regression model was used to account for imbalances in baseline characteristics; a consistent HR was observed for everolimus plus exemestane vs everolimus (0.73; 90% CI, 0.56-0.97), but the HR was closer to 1 for everolimus plus exemestane vs capecitabine (1.15; 90% CI, 0.86-1.52). Grade 3 to 4 adverse events were more frequent with capecitabine (74%; n = 75) vs everolimus plus exemestane (70%; n = 73) or everolimus alone (59%; n = 61). Serious adverse events were more frequent with everolimus plus exemestane (36%; n = 37) vs everolimus alone (29%; n = 30) or capecitabine (29%; n = 30).

Conclusions and Relevance

These findings suggest that everolimus plus exemestane combination therapy offers a PFS benefit vs everolimus alone, and they support continued use of this therapy in this setting. A numerical PFS difference with capecitabine vs everolimus plus exemestane should be interpreted cautiously owing to imbalances among baseline characteristics and potential informative censoring.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01783444

Introduction

In the phase 3 BOLERO-2 study,1,2 everolimus plus exemestane significantly improved median progression-free survival (PFS) vs placebo plus exemestane (7.8 vs 3.2 months, hazard ratio [HR] 0.45, 95% CI, 0.38-0.54) in patients whose hormone receptor (HR)-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative, advanced breast cancer had progressed while the patient was undergoing treatment with a nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor, leading to the approval of this combination.1,2

Capecitabine is indicated with docetaxel for patients when anthracycline-containing chemotherapy has failed and as a monotherapy for patients when taxanes and anthracycline-containing chemotherapy have failed or for whom further anthracycline-containing therapy is not indicated.3,4 In the clinical practice setting, capecitabine is often given as the first chemotherapeutic agent for patients with estrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancer that has progressed during antiestrogen therapy. The RIBBON-1 study reported that capecitabine had a median PFS of 6.2 months.5 A small phase 2 study showed that everolimus alone had some clinical activity (median PFS 3.5 months).6 To our knowledge, everolimus alone has not been evaluated vs everolimus plus exemestane in a clinical practice setting. Given the different safety profiles of capecitabine and everolimus plus exemestane, that they are distinct classes of therapeutic agent, and the limited data available for everolimus monotherapy, evaluation of these treatments in a randomized clinical setting was warranted.

BOLERO-6 was conducted to fulfill postapproval regulatory commitments to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) to estimate treatment benefit with everolimus plus exemestane vs everolimus alone or capecitabine alone in patients with ER-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer that progressed during treatment with a nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

BOLERO-6 was an open-label, phase 2, randomized clinical trial conducted at 83 medical centers across 18 countries (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). The combined trial protocol and statistical analysis plan are provided in Supplement 2. Patients were enrolled between March 4, 2013, and November 24, 2014. All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment. Study conduct adhered to Good Clinical Practice guidelines, local regulations, and the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the institutional review boards, independent ethics committee, and/or research ethics boards at each study center.

Participants

Patients were postmenopausal women with ER-positive, HER2-negative metastatic or recurrent breast cancer, or locally advanced breast cancer not amenable to curative surgery or radiotherapy, whose disease had recurred or progressed during treatment with letrozole or anastrozole. Patients were required to have measurable disease per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST, version 1.1) or bone lesions (lytic or mixed), and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 to 2. Patients who received more than 1 prior line of chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer, prior treatment with exemestane or inhibitors of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), or protein kinase B, or with known hypersensitivity to mTOR inhibitors, capecitabine (or any of its components), or fluorouracil, were excluded. Further eligibility criteria are provided in eMethods in Supplement 1.

Procedures

The primary objective was to estimate the HR of PFS for everolimus plus exemestane vs everolimus alone. The primary end point was PFS, defined as the time from randomization to first documented progression or death due to any cause. The key secondary objective was to estimate the HR of PFS for everolimus plus exemestane vs capecitabine. Additional secondary end points included overall survival (OS), overall response rate (ORR), clinical benefit rate (CBR), and safety.

Tumors were investigator-assessed per RECIST, version 1.1 with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging at screening and every 6 weeks after randomization until disease progression, loss to follow-up, withdrawal of consent, or investigator decision.

Safety was assessed by adverse event (AE) frequency, graded per the CTCAE (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events), version 4.0. Patients were followed up for safety up to 30 days after receiving the last dose of study treatment. The first antineoplastic therapy initiated after discontinuation of the study treatment was recorded in the patients’ electronic case report form.

Patients were randomized 1:1:1 to receive 1 of the following treatments: (1) oral everolimus, 10 mg/d (two 5-mg tablets) plus oral exemestane (25 mg/d); (2) oral everolimus alone (10 mg/d); or (3) oral capecitabine alone (1250 mg/m2 twice daily for 14 days of a 21-day cycle). Randomization was stratified by visceral disease status. Randomization procedures are detailed in eMethods in Supplement 1.

Patients received treatment until disease progression, unacceptable toxic effects, withdrawal of consent, or investigator decision. Patients randomized to everolimus plus exemestane who discontinued either treatment for reasons other than disease progression could continue receiving the combination partner as a monotherapy. Dose adjustments were permitted (eMethods in Supplement 1).

Statistical Analysis

Efficacy was analyzed in all randomized patients (full analysis set). Safety was analyzed in all patients who received 1 or more doses of study treatment, and 1 or more postbaseline safety assessments (safety set).

The BOLERO-6 trial was designed to provide estimates of treatment effect and not powered to perform statistical comparisons between study arms. A Cox regression model stratified by visceral disease status was used to estimate the HR of PFS and OS. Accompanying 90% CIs were preplanned to align with the sample size calculation, which was based on the precision of the estimate (width of the 90% CI of the HR) (eMethods in Supplement 1); 95% CIs are provided in eTables 4-5 in Supplement 1. Additional stratified multivariate Cox regression models of PFS and OS were adjusted on treatment on the following prognostic and baseline covariates where imbalances between arms were observed: bone-only lesions at baseline (yes vs no); prior chemotherapy use (yes vs no); ECOG performance status (0 vs 1-2); organs involved (2 vs 1, and ≥3 vs 1); race (white vs nonwhite); age (<65 vs ≥65 years).

Median PFS and median OS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and presented with 90% CIs. The PFS was censored at the date of the last adequate tumor assessment for the following reasons: no PFS event was observed by the analysis cutoff; loss to follow-up; consent withdrawal; adequate assessment no longer available; documentation of an event after 2 or more missing tumor assessments; initiation of a new anticancer therapy. The OS was censored at the date of last contact if no death was observed by the analysis cutoff or if the patient was lost to follow-up. The ORR and CBR were estimated using the Clopper-Pearson method and presented with 90% CIs. Time to treatment failure (TTF) defined as the time from randomization to progression, discontinuation of treatment for other reasons than protocol deviation or administrative problems, or death, whichever occurred first, was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method and stratified Cox model to estimate the HRs.

An interim PFS analysis was conducted to allow early termination of the everolimus monotherapy arm in the event of far inferior efficacy vs everolimus plus exemestane (eMethods in Supplement 1). Confidence intervals were not adjusted for this interim PFS analysis.

Results

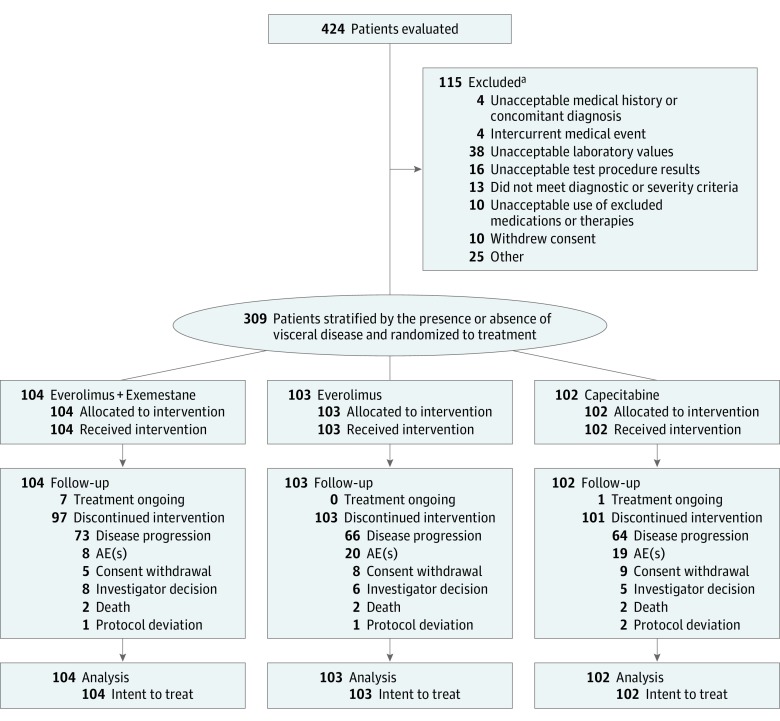

A total of 309 patients were randomized to receive everolimus plus exemestane (n = 104), everolimus alone (n = 103), or capecitabine alone (n = 102) (Figure 1). Overall, median patient age was 61 years (range, 32-88 years). Baseline characteristics are summarized in eTable 2 in Supplement 1. A larger proportion of patients in the capecitabine arm vs the everolimus plus exemestane and everolimus alone arms were white (n = 91, 89% vs n = 78, 75% and n = 85, 83%, respectively), younger than 65 years (n = 69, 68% vs n = 65, 63% and n = 64, 62%), had ECOG performance status of 0 (n = 57, 56% vs n = 54, 52% and n = 48, 47%), or had bone-only metastases (n = 24, 24% vs n = 13, 13% and n = 16, 16%), while fewer patients in the capecitabine arm had 3 or more metastatic sites (n = 45, 44% vs n = 52, 50% and n = 47, 46%).

Figure 1. Study Enrollment Flow Diagram.

Discontinued intervention is defined as the primary reason for treatment discontinuation. AE indicates adverse event.

aSome patients had multiple reasons for study exclusion.

Median follow-up from randomization to the analysis cutoff (June 1, 2017) was 37.6 months. At the analysis cutoff, treatment was ongoing in 7 patients in the everolimus plus exemestane arm (7%) and 1 patient in the capecitabine arm (1%). Median exposure was 27.5 weeks with everolimus plus exemestane, 20.0 weeks with everolimus, and 26.7 weeks with capecitabine. Median relative dose intensities of everolimus and exemestane in the combination arm were 0.92 and 1.00, respectively. Median relative dose intensities of everolimus and capecitabine in the monotherapy arms were 0.98 and 0.78, respectively.

Primary reasons for treatment discontinuation across the 3 arms were disease progression (n = 203, 66%) and AEs (n = 47, 15%) (Figure 1). Discontinuations owing to disease progression were more frequent with everolimus plus exemestane (n = 73, 70%) vs everolimus alone (n = 66, 64%) and capecitabine (n = 64, 63%). Discontinuations owing to AEs were more frequent with everolimus alone (n = 20, 19%) and capecitabine (n = 19, 19%) vs everolimus plus exemestane (n = 8, 8%). Eight patients receiving everolimus plus exemestane discontinued everolimus owing to AEs, resulting in 17% of patients (n = 18) reporting an AE leading to discontinuation for 1 or more of the study treatments in the combination arm.

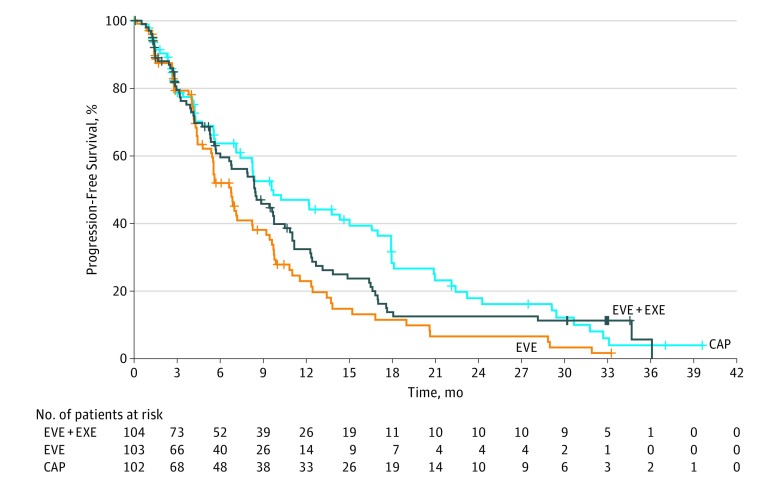

There were 154 PFS events between the everolimus plus exemestane (n = 80) and everolimus alone (n = 74) arms. In the primary analysis, median PFS was 8.4 months with everolimus plus exemestane vs 6.8 months with everolimus alone, corresponding to an estimated 26% reduction of risk of disease progression or death (HR, 0.74; 90% CI, 0.57-0.97) (Figure 2). A stratified multivariate Cox regression model was used to account for baseline imbalances in patient characteristics and adjusted for known prognostic factors; a consistent HR was observed (0.73; 90% CI, 0.56-0.97). Compared with the everolimus plus exemestane arm, censoring was more frequent in the everolimus arm, especially for initiating new antineoplastic therapies (n = 19, 18% vs n = 9, 9%). Median TTF, considering all reasons for stopping treatment as an event, was 5.8 months with everolimus plus exemestane vs 4.2 months with everolimus alone (HR, 0.66; 90% CI, 0.52-0.84).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Curves of Progression-free Survival for Everolimus Plus Exemestane vs Everolimus Alone and Capecitabine Alone.

CAP indicates capecitabine; EVE, everolimus; EXE, exemestane; HR, hazard ratio.

There were 148 PFS events between the everolimus plus exemestane (n = 80) and capecitabine (n = 68) arms. Median PFS was 8.4 months with everolimus plus exemestane vs 9.6 months with capecitabine (HR, 1.26; 90% CI, 0.96-1.66) (Figure 2). Compared with the everolimus plus exemestane arm, censoring was more frequent in the capecitabine arm (n = 34, 33% vs n = 24, 23%), especially for initiating new antineoplastic therapies (n = 20, 20% vs n = 9, 9%). Among patients censored owing to initiating antineoplastic therapies in the capecitabine arm, 65% discontinued treatment for safety reasons (n = 13 of 20). Median TTF was 5.8 months with everolimus plus exemestane vs 6.2 months with capecitabine (HR, 1.03; 90% CI, 0.81-1.31). A stratified multivariate Cox regression model of PFS, adjusted on prognostic factors and baseline characteristics where imbalances between arms were observed, produced an HR closer to 1 for everolimus plus exemestane vs capecitabine (HR, 1.15; 90% CI, 0.86-1.52).

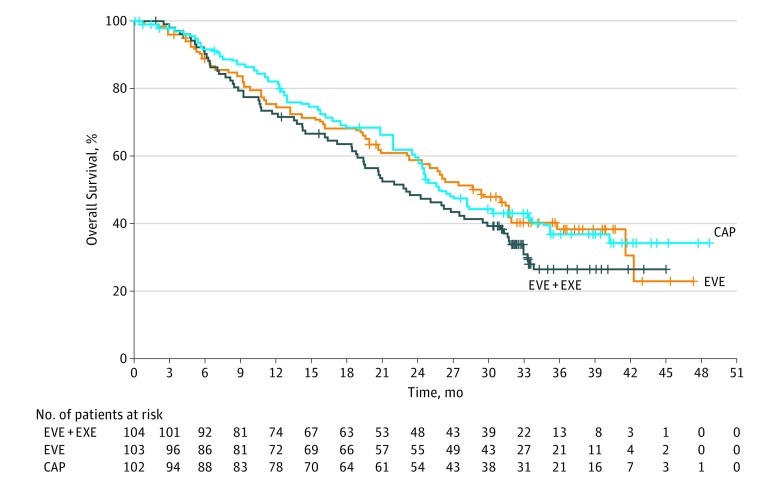

Median OS was 23.1 months with everolimus plus exemestane vs 29.3 months with everolimus alone (HR, 1.27; 90% CI, 0.95-1.70) and 25.6 months with capecitabine (HR, 1.33; 90% CI, 0.99-1.79) (Figure 3). A stratified multivariate Cox regression model, adjusted on prognostic factors and baseline characteristics where imbalances between arms were observed, produced an HR of 1.27 (90% CI, 0.94-1.70) for everolimus plus exemestane vs everolimus alone and an HR closer to 1 for everolimus plus exemestane vs capecitabine (HR, 1.19; 90% CI, 0.88-1.62). On treatment discontinuation, antineoplastic therapies were initiated by 81 patients (78%) receiving everolimus plus exemestane and 83 patients (81%) receiving everolimus alone, with capecitabine the most common therapy that was given first in each arm (n = 20; 19% each). Eighty-one patients (79%) receiving capecitabine also initiated antineoplastic therapies, with everolimus plus exemestane the most common therapy that was given first (n = 12, 12%) (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). The ORR and CBR are detailed in eTable 4 in Supplement 1.

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier Curves of Overall Survival for Everolimus Plus Exemestane vs Everolimus Alone and Capecitabine Alone.

CAP indicates capecitabine; EVE, everolimus; EXE, exemestane; HR, hazard ratio.

All patients were assessed for safety, and dose interruptions and reductions are detailed in eTable 6 in Supplement 1. All-grade and grade 3 to 4 AEs regardless of causality are listed in the Table. The most common all-grade AEs were stomatitis with everolimus plus exemestane (n = 51, 49%) and everolimus alone (n = 47, 46%), and palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia (PPE) syndrome (n = 62, 61%) and diarrhea (n = 55, 54%) with capecitabine. The most common grade 3 to 4 AEs were anemia with everolimus plus exemestane (n = 13, 13%), elevated γ-glutamyl transferase with everolimus alone (n = 12, 12%), and PPE syndrome with capecitabine (n = 28, 27%). Serious AEs regardless of causality are detailed in eTable 7 in Supplement 1; the most common were pneumonia with everolimus plus exemestane (n = 8, 8%), pneumonia and acute kidney injury with everolimus alone (n = 4, 4% each), and deep vein thrombosis (n = 4, 4%) with capecitabine. The AEs leading to study drug discontinuation regardless of causality are detailed in eTable 8 in Supplement 1; the most common were pneumonitis with everolimus plus exemestane (n = 3, 3%) and everolimus alone (n = 5, 5%) and PPE syndrome with capecitabine (n = 5, 5%).

Table. Adverse Events Regardless of Causalitya.

| Adverse Event | Patients, No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Everolimus + Exemestane (n = 104) | Everolimus (n = 103) | Capecitabine (n = 102) | ||||

| Any Grade | Grade 3-4 | Any Grade | Grade 3-4 | Any Grade | Grade 3-4 | |

| Total | 104 (100) | 73 (70) | 101 (98) | 61 (59) | 102 (100) | 75 (74) |

| Stomatitis | 51 (49) | 9 (9) | 47 (46) | 5 (5) | 25 (25) | 7 (7) |

| Fatigue | 39 (38) | 8 (8) | 32 (31) | 3 (3) | 36 (35) | 8 (8) |

| Diarrhea | 36 (35) | 5 (5) | 34 (33) | 3 (3) | 55 (54) | 8 (8) |

| Anemia | 33 (32) | 13 (13) | 26 (25) | 10 (10) | 22 (22) | 7 (7) |

| Elevated γ-GGT | 16 (15) | 9 (9) | 16 (16) | 12 (12) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Elevated AST | 16 (15) | 7 (7) | 14 (14) | 8 (8) | 9 (9) | 1 (1) |

| Hypertension | 15 (14) | 6 (6) | 8 (8) | 2 (2) | 5 (5) | 3 (3) |

| Hyperglycemia | 13 (13) | 4 (4) | 18 (17) | 8 (8) | 8 (8) | 1 (1) |

| Pneumonia | 11 (11) | 7 (7) | 9 (9) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) |

| Neutropenia | 4 (4) | 0 | 4 (4) | 2 (2) | 15 (15) | 6 (6) |

| PPE syndrome | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 0 | 62 (61) | 28 (27) |

Abbreviations: AST, aspartate aminotransferase; γ-GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; PPE, palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia.

Reported are grade 3 to 4 adverse events with higher than 5% incidence in any of the treatment arms. Some patients have more than 1 adverse event.

Overall, 188 patients died during the study: 71 in the everolimus plus exemestane arm, 59 in the everolimus arm, and 58 in the capecitabine arm, with disease progression the most common reason in each arm. Sixteen of these deaths occurred during treatment (≤30 days after end of treatment): 9 in the everolimus plus exemestane arm, 5 in the everolimus alone arm, and 2 in the capecitabine arm. Disease progression was the most common reason for death in the everolimus plus exemestane arm (n = 6); AEs were the most common reason in the monotherapy arms: acute kidney injury, cardiorespiratory arrest, and respiratory failure—1 event each—in the everolimus monotherapy arm; and cerebrovascular accident and septic shock—1 event each—in the capecitabine monotherapy arm (eTable 9 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

This was an open-label, phase 2 study conducted to fulfill a postapproval regulatory commitment to the US FDA and EMA. Median PFS with everolimus plus exemestane in patients with ER-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer was 8.4 months (90% CI, 6.6-9.7 months), consistent with that reported in the BOLERO-2 study (7.8 months).1 It was also numerically longer than that with everolimus alone in this study (6.8 months; 90% CI, 5.5-7.2 months), corresponding to an estimated 26% reduction of risk of disease progression or death (HR, 0.74; 90% CI, 0.57-0.97). Median PFS with everolimus alone was numerically longer than that reported in a small phase 2 study (3.5 months; 95% CI, 1.9-5.5 months),6 although this outcome was observed in just 19 patients.

A numerical PFS difference in favor of capecitabine (median 9.6 months; 90% CI, 8.3-15.1 months) vs everolimus plus exemestane should be interpreted cautiously because the capecitabine outcome was inconsistent with previous capecitabine studies (PFS range, 4.1-7.9 months).5,7,8,9,10 The PFS difference between the 2 arms might also be attributed to informative censoring in the context of an open-label study as well as imbalances in prognostic factors and baseline characteristics. More patients were censored owing to initiating antineoplastic therapies who received capecitabine (20%) than everolimus plus exemestane (9%). Such patients may not have the same PFS prognosis as those censored for other reasons and thus could bias the PFS estimate. The TTF was found to be similar between everolimus plus exemestane and capecitabine (HR, 1.03; 90% CI, 0.81-1.31), supporting the assumption of informative censoring in the PFS analysis favoring the capecitabine arm.

The median OS observed with everolimus plus exemestane (23.1 months; 90% CI, 19.5-28.0 months; 95% CI, 18.9-29.5 months) was inconsistent with the BOLERO-2 study (31.0 months; 95% CI, 28.0-34.6 months),11 with a similar median follow-up time (approximately 4 years). A random effect due to the small sample size in this study (n = 104 vs n = 485 in BOLERO-2) cannot be ruled out. Another contributing factor may have been different patterns of antineoplastic therapies initiated between the 2 studies after treatment discontinuation; however, any analysis is limited by documentation of only the first-line antineoplastic therapy initiated by patients in both studies. In BOLERO-2, more patients had an ECOG performance status of 0, and fewer had 3 or more metastatic sites than in the present study, although these factors were not found to have influenced the results. Median OS with everolimus plus exemestane was also numerically shorter vs everolimus alone (29.3 months; 90% CI, 24.3-31.8 months) and capecitabine (25.6 months; 90% CI, 23.8-33.4 months) in the present study. While no clear reasons were apparent to explain the discrepancy between the PFS and OS results with everolimus plus exemestane vs everolimus alone, the median OS with capecitabine in the present study was consistent with previous capecitabine studies (18.6-29.4 months).5,7,8,9,10 These results should also be interpreted cautiously because there were some potential imbalances in baseline characteristics that may have been influential.

Regarding safety, incidences of AEs and on-treatment deaths due to AEs (ie, AE-related deaths occurring up to 30 days after the end of treatment) were comparable among the 3 treatment arms. Stomatitis and the related AE of mouth ulceration were more common with everolimus plus exemestane and everolimus alone than with capecitabine, although stomatitis is a class effect1 of mTOR inhibitors,12,13 and everolimus-associated stomatitis has been well documented.2,12,14,15 The incidence and severity of stomatitis would likely be lower using current practices because BOLERO-6 was designed prior to the results of the SWISH study,16 which supported initiation of topical treatment with dexamethasone mouthwash when starting everolimus treatment. The safety profile of everolimus plus exemestane was therefore consistent with BOLERO-2,1 and no new safety signals were observed; the overall benefit-risk profile of this combination remains unchanged. Everolimus in combination with other endocrine therapies also demonstrated a similar safety profile and no new safety signals.17,18,19,20 The incidence of PPE syndrome observed in the capecitabine arm was consistent with previous studies of capecitabine monotherapy.7,8,9,10

Limitations

This was not a phase 3 confirmatory study, and any interpretation of the results must consider the limited sample size and open-label design. Insights are required from other studies comparing endocrine therapy and targeted therapy combinations with capecitabine for ER-positive advanced breast cancer, such as the ongoing phase 3 PEARL study (NCT02028507).

Conclusions

The treatment landscape for HR-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer now includes cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors and endocrine therapy combinations. However, with the optimal sequence of endocrine agents following first-line endocrine therapy still uncertain, postapproval studies continue to provide valuable insights. The results of the present study suggest that mTOR inhibitor and endocrine therapy combinations remain important for aromatase inhibitor–refractory disease. Safety and PFS with everolimus plus exemestane in this study were consistent with BOLERO-2 and are now supported by real-world evidence.21,22,23 The PFS with capecitabine in this study was inconsistent with historical data, while real-world data are also lacking. Both PFS and OS for everolimus plus exemestane vs capecitabine may have been confounded by baseline imbalances favoring capecitabine and by informative censoring. The unchanged benefit-risk profile shown by everolimus plus exemestane in this study therefore supports retention of this combination as an option for patients with advanced breast cancer.

eMethods. Study Design and Participants, Procedures, Sample Size Calculation, Interim Analysis

eTable 1. BOLERO-6 Recruitment Sites

eTable 2. Baseline Patient Demographics and Disease Characteristics

eTable 3. First-Line Antineoplastic Therapies Initiated Following Treatment Discontinuation

eTable 4. Efficacy Analysis, Per Local Investigator Review (Full Analysis Set)

eTable 5. Analysis of OS, Per Local Investigator Review (Full Analysis Set)

eTable 6. Dose Interruptions and Reductions

eTable 7. Serious Adverse Events (≥1.5% Incidence in Any Arm), Regardless of Causality

eTable 8. Adverse Events Leading to Treatment Discontinuation (≥1.5% Incidence in Any Arm), Regardless of Causality

eTable 9. Summary of Deaths

eReferences.

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

References

- 1.Baselga J, Campone M, Piccart M, et al. Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(6):1367-1374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yardley DA, Noguchi S, Pritchard KI, et al. Everolimus plus exemestane in postmenopausal patients with HR(+) breast cancer: BOLERO-2 final progression-free survival analysis. Adv Ther. 2013;30(10):870-884. doi: 10.1007/s12325-013-0060-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardoso F, Costa A, Senkus E, et al. 3rd ESO-ESMO international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC 3). Breast. 2017;31:244-259. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2016.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN guidelines): breast cancer; V1. 2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx. Accessed May 11, 2018.

- 5.Robert NJ, Diéras V, Glaspy J, et al. RIBBON-1: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial of chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab for first-line treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative, locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(10):1252-1260. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.0982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellard SL, Clemons M, Gelmon KA, et al. Randomized phase II study comparing two schedules of everolimus in patients with recurrent/metastatic breast cancer: NCIC Clinical Trials Group IND.163. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(27):4536-4541. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.3033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Shaughnessy JA, Kaufmann M, Siedentopf F, et al. Capecitabine monotherapy: review of studies in first-line HER-2-negative metastatic breast cancer. Oncologist. 2012;17(4):476-484. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stockler MR, Harvey VJ, Francis PA, et al. Capecitabine versus classical cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil as first-line chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(34):4498-4504. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.9101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaufmann M, Maass N, Costa SD, et al. ; GBG-39 Trialists . First-line therapy with moderate dose capecitabine in metastatic breast cancer is safe and active: results of the MONICA trial. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(18):3184-3191. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harbeck N, Saupe S, Jäger E, et al. ; PELICAN Investigators . A randomized phase III study evaluating pegylated liposomal doxorubicin versus capecitabine as first-line therapy for metastatic breast cancer: results of the PELICAN study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;161(1):63-72. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-4033-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piccart M, Hortobagyi GN, Campone M, et al. Everolimus plus exemestane for hormone-receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2-negative advanced breast cancer: overall survival results from BOLERO-2. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(12):2357-2362. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rugo HS, Pritchard KI, Gnant M, et al. Incidence and time course of everolimus-related adverse events in postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer: insights from BOLERO-2. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(4):808-815. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Divers J, O’Shaughnessy J. Stomatitis associated with use of mTOR inhibitors: implications for patients with invasive breast cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19(4):468-474. doi: 10.1188/15.CJON.468-474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rugo HS, Hortobagyi GN, Yao J, et al. Meta-analysis of stomatitis in clinical studies of everolimus: incidence and relationship with efficacy. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(3):519-525. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shameem R, Lacouture M, Wu S. Incidence and risk of high-grade stomatitis with mTOR inhibitors in cancer patients. Cancer Invest. 2015;33(3):70-77. doi: 10.3109/07357907.2014.1001893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rugo HS, Seneviratne L, Beck JT, et al. Prevention of everolimus-related stomatitis in women with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer using dexamethasone mouthwash (SWISH): a single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(5):654-662. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30109-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmid P, Zaiss M, Harper-Wynne C, et al. MANTA: a randomized phase II study of fulvestrant in combination with the dual mTOR inhibitor AZD2014 or everolimus or fulvestrant alone in estrogen receptor-positive advanced or metastatic breast cancer [abstract GS2-07]. Presented at San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; December 5-9, 2017; San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bachelot T, Bourgier C, Cropet C, et al. Randomized phase II trial of everolimus in combination with tamoxifen in patients with hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative metastatic breast cancer with prior exposure to aromatase inhibitors: a GINECO study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(22):2718-2724. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.0708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baselga J, Semiglazov V, van Dam P, et al. Phase II randomized study of neoadjuvant everolimus plus letrozole compared with placebo plus letrozole in patients with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(16):2630-2637. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.8391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kornblum N, Manola J, Klein P, et al. PrECOG 0102: a randomized, double-blind, phase II trial of fulvestrant plus everolimus or placebo in post-menopausal women with hormone receptor (HR)-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer (MBC) resistant to aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy [abstract S1-02]. Presented at: San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; December 6-10, 2016; San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lousberg L, Jerusalem G. Safety, efficacy, and patient acceptability of everolimus in the treatment of breast cancer. Breast Cancer (Auckl). 2017;10:239-252. doi: 10.4137/BCBCR.S12443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jerusalem G, Mariani G, Ciruelos EM, et al. Safety of everolimus plus exemestane in patients with hormone-receptor-positive, HER2-negative locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer progressing on prior non-steroidal aromatase inhibitors: primary results of a phase IIIb, open-label, single-arm, expanded-access multicenter trial (BALLET). Ann Oncol. 2016;27(9):1719-1725. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steger G, Bartsch R, Pfeiler G, et al. Efficacy and safety of everolimus plus exemestane in HR+, HER2– advanced breast cancer progressing on/after prior endocrine therapy, in routine clinical practice: second interim analysis from STEPAUT. Cancer Res 2017;77(4 Supplement):[Abstract P4-22-20]. Presented at: San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; December 6-10, 2016; San Antonio, Texas. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Study Design and Participants, Procedures, Sample Size Calculation, Interim Analysis

eTable 1. BOLERO-6 Recruitment Sites

eTable 2. Baseline Patient Demographics and Disease Characteristics

eTable 3. First-Line Antineoplastic Therapies Initiated Following Treatment Discontinuation

eTable 4. Efficacy Analysis, Per Local Investigator Review (Full Analysis Set)

eTable 5. Analysis of OS, Per Local Investigator Review (Full Analysis Set)

eTable 6. Dose Interruptions and Reductions

eTable 7. Serious Adverse Events (≥1.5% Incidence in Any Arm), Regardless of Causality

eTable 8. Adverse Events Leading to Treatment Discontinuation (≥1.5% Incidence in Any Arm), Regardless of Causality

eTable 9. Summary of Deaths

eReferences.

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan