This cohort study using data from the US National Cancer Database assesses the patterns of use and the effectiveness of adjuvant endocrine therapy for hormone receptor–positive breast cancer in men.

Key Points

Question

What are the US national patterns of use and benefits associated with adjuvant endocrine therapy in men with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer?

Findings

In this cohort study of 10 173 men with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer, adjuvant endocrine therapy was underused among eligible men (67%) despite an overall survival benefit (7% at 10 years) associated with its use.

Meaning

Because adjuvant endocrine therapy is associated with improved overall survival among men with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer, further efforts are needed to improve use of this therapy in eligible males.

Abstract

Importance

Although adjuvant endocrine therapy confers a survival benefit among females with hormone receptor (HR)–positive breast cancer, the effectiveness of this treatment among males with HR-positive breast cancer has not been rigorously investigated.

Objective

To investigate trends, patterns of use, and effectiveness of adjuvant endocrine therapy among men with HR-positive breast cancer.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study identified patients in the National Cancer Database with breast cancer who had received treatment from 2004 through 2014. Inclusion criteria for the primary study cohort were males at least 18 years old with nonmetastatic HR-positive invasive breast cancer who underwent surgery with or without adjuvant endocrine therapy. A cohort of female patients was also identified using the same inclusion criteria for comparative analyses by sex. Data analysis was conducted from October 1, 2017, to December 15, 2017.

Exposures

Receipt of adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Patterns of adjuvant endocrine therapy use were assessed using multivariable logistic regression analyses. Association between adjuvant endocrine therapy use and overall survival was assessed using propensity score-weighted multivariable Cox regression models.

Results

The primary study cohort comprised 10 173 men with HR-positive breast cancer (mean [interquartile range] age, 66 [57-75] years). The comparative cohort comprised 961 676 women with HR-positive breast cancer (mean [interquartile range] age, 62 [52-72] years). The median follow-up for the male cohort was 49.6 months (range, 0.1-142.5 months). Men presented more frequently than women with HR-positive disease (94.0% vs 84.3%, P < .001). However, eligible men were less likely than women to receive adjuvant endocrine therapy (67.3% vs 79.0%; OR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.58-0.63; P < .001). Treatment at academic facilities (odds ratio, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.02-1.25; P = .02) and receipt of adjuvant radiotherapy (odds ratio, 2.83; 95% CI, 2.55-3.15; P < .001) or chemotherapy (odds ratio, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.07-1.34; P < .001) were statistically significantly associated with adjuvant endocrine therapy use in men. A propensity score-weighted analysis indicated that relative to no use, adjuvant endocrine therapy use in men was associated with improved overall survival (hazard ratio, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.63-0.77; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

There is a sex disparate underuse of adjuvant endocrine therapy among men with HR-positive breast cancer despite the use of this treatment being associated with improved overall survival. Further research and interventions may be warranted to bridge gaps in care in this population.

Introduction

Male breast cancer is a rare malignant neoplasm that accounts for approximately 1% of all newly diagnosed breast cancers.1 Because of a paucity of research, therapeutic strategies for male breast cancer are commonly extrapolated from those used to treat female breast cancer.2

An example of such extrapolation is the use of adjuvant endocrine therapy (AET) among males with hormone receptor (HR)–positive breast cancer. Although evidence from randomized trials convincingly demonstrates an overall survival (OS) benefit with the use of AET for females with HR-positive breast cancer,3,4 studies assessing the efficacy of AET in males are limited to small retrospective single-institution studies.5,6,7,8 Although guidelines recommend AET for male patients with HR-positive disease on the strength of data accumulated among female patients,2 it remains unclear whether AET confers a similar benefit in both sexes.

To investigate further, we performed a retrospective observational cohort study using the National Cancer Database9 to assess trends, patterns of care, and efficacy associated with AET use among men with HR-positive breast cancer.

Methods

Inclusion criteria (eFigure 1 in the Supplement) for the male cohort consisted of patients in the National Cancer Database who were at least 18 years old with pathologic stage I through III HR-positive (defined as being positive for estrogen or progesterone receptors) invasive breast carcinoma that was treated with either lumpectomy or mastectomy from 2004 through 2014. A cohort of female patients was identified from the database for comparative analyses using the same inclusion criteria.

The male cohort was dichotomized for primary analyses into no AET and AET cohorts. Concordance with guideline-based care was assessed at patient and hospital levels. Hospitals were considered concordant with guideline-based care if 80% or more of males with HR-positive breast cancer treated at the facility received AET. This study was deemed exempt from review by the University of Pennsylvania institutional review board in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act given the use of a deidentified data set. As such, the need for written informed consent by participants was waived.

Patient baseline characteristics were compared using χ2 tests. A multivariable logistic regression model was fitted using stepwise selection and a univariable inclusion criterion of P < .10 to assess the independent effects of covariates on the likelihood of receipt of AET. Overall survival was defined as the time from diagnosis until death or until the last follow-up. Variables trending toward significance (P < .10) using a univariable analysis were included in a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model to assess the independent effect of receipt of AET on OS. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier methods, and log-rank tests were used to compare OS between cohorts. Propensity score adjustment using inverse probability of treatment weighting with robust variance estimation10 was used to further adjust for potential measured confounding. Covariate balance following propensity score weighting was assessed using standardized differences of means. Survival analyses were then repeated using the inverse probability of treatment weighting model.

Subgroup analyses were performed to assess the benefit of AET among various patient cohorts. The Bonferroni method11 was applied to account for multiple testing in the subgroup analysis. All tests were 2 tailed, and a 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed from October 1, 2017, to December 15, 2017, using R, version 3.3.2 (R Foundation).

Results

Among the 10 173 men identified with HR-positive breast cancer, 3326 men (32.7%) did not receive AET and 6847 men (67.3%) received AET (Table 1). The median age of the cohort was 66 years (interquartile range, 57-75 years), and the median follow-up time was 49.6 months (range, 0.1-142.5 months). Complete baseline characteristics are provided in eTable 1 in the Supplement.

Table 1. Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Primary Male Cohorta.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | P Valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without AET | With AET | Total | ||

| Total | 3326 (32.7) | 6847 (67.3) | 10 173 (100) | |

| Age, y | ||||

| 18-49 | 379 (11.3) | 795 (11.6) | 1174 (11.5) | <.001 |

| 50-69 | 1487 (44.7) | 3401 (49.7) | 4888 (48.0) | |

| ≥70 | 1460 (43.9) | 2651 (38.7) | 4111 (40.4) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 2694 (81.0) | 5737 (83.8) | 8431 (82.9) | .003 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 380 (11.4) | 704 (10.3) | 1084 (10.6) | |

| Hispanic | 117 (3.5) | 185 (2.7) | 302 (3.0) | |

| Other | 135 (4.0) | 221 (3.2) | 356 (3.5) | |

| Charlson-Deyo comorbidity score | ||||

| 0 | 2571 (77.3) | 5364 (78.3) | 7935 (78.0) | .28 |

| 1 | 569 (17.1) | 1147 (16.8) | 1716 (16.9) | |

| 2 | 186 (5.6) | 336 (4.9) | 522 (5.1) | |

| Pathologic stage | ||||

| I | 1421 (42.7) | 2756 (40.2) | 4177 (41.0) | .009 |

| II | 1371 (41.2) | 3041 (44.4) | 4412 (43.4) | |

| III | 534 (16.0) | 1050 (15.3) | 1584 (15.6) | |

Abbreviation: AET, adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Only select characteristics are given herein. All examined characteristics are provided in eTable 1 in the Supplement.

χ2 Test.

Relative to the 1 141 648 women included in the present study, men were statistically significantly more likely to present with HR-positive breast cancer (94.0% vs 84.3%; P < .001 determined by χ2 test), higher grade disease (eg, grade 3, 31.8% vs 28.3%; P < .001 determined by χ2 test), and higher pathologic stage (eg, stage III, 15.4% vs 9.2%; P < .001 determined by χ2 test) (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Despite presenting more often with HR-positive disease, men were less likely than women to receive AET (67.3% vs 78.9%; odds ratio [OR], 0.61; 95% CI, 0.58-0.63; P < .001).

Concordance rates for AET use increased from 53.6% in 2004 to 73.9% in 2014 at the patient level, and from 43.9% in 2004 to 63.0% in 2014 at the hospital level (P < .001) (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). The results of a multivariable analysis (eTable 3 in the Supplement) indicated that the odds of AET use were increased with treatment at academic vs nonacademic facilities (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.02-1.25; P = .02) and with receipt of adjuvant radiotherapy (OR, 2.83; 95% CI, 2.55-3.15; P < .001) or chemotherapy (OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.07-1.34; P < .001).

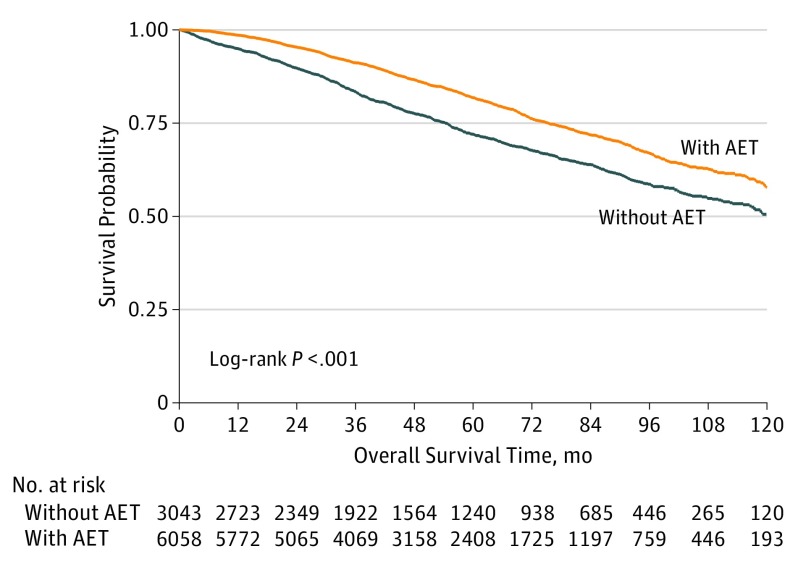

The multivariable analysis results (Table 2 and eTable 4 in the Supplement) indicated that AET use was associated with improved OS (hazard ratio, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.65-0.79; P < .001). The median OS was 11.0 years (interquartile range, 6.3 years to not reached) in the AET cohort and 10.3 years (interquartile range, 4.5 years to not reached) in the cohort without AET, corresponding to a 5-year OS estimate of 81.8% in the AET cohort vs 72.0% in the cohort without AET and a 10-year OS estimate of 57.8% in the AET cohort vs 50.6% in the cohort without AET (Figure).

Table 2. Factors Associated With Overall Survivala.

| Factor | Multivariable | |

|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Adjuvant endocrine treatmentb | ||

| None | 1 [Reference] | <.001 |

| Yes | 0.72 (0.65-0.79) | |

| Facility type | ||

| Nonacademic | 1 [Reference] | <.001 |

| Academic | 0.81 (0.73-0.91) | |

| Unknown | Omitted | |

| Pathologic stage | ||

| I | 1 [Reference] | |

| II | 1.07 (0.90-1.27) | .43 |

| III | 1.88 (1.52-2.34) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weighting.

Only selected factors are given herein; full information is provided in eTable 4 in the Supplement.

IPTW hazard ratio for the primary outcome of interest alone, 0.70 (95% CI, 0.63-0.77); P < .001.

Figure. Overall Survival of Patients With or Without Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy (AET).

The propensity score–weighted multivariable analysis indicated that AET use remained associated with improved OS (inverse probability of treatment weighting hazard ratio, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.63-0.77; P < .001). For the subgroup analysis (eFigure 3 in the Supplement), a statistically significant OS benefit for AET use persisted in all groups except for patients with pathologic stage III disease.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first cancer registry-based investigation examining the effectiveness of AET for male breast cancer. We showed an association between AET use and improved OS among males with nonmetastatic HR-positive breast cancer. This association was present in various subgroups stratified by age, nodal status, disease stage, and receipt of adjuvant therapy.

Our findings suggested an underuse of AET because approximately 33% of eligible male patients did not receive this potentially life-saving treatment. Moreover, eligible men received AET less frequently than women did, indicating sex disparity in care. Such underuse may be explained by the lack of evidence-based guidelines for males,2 poor tolerability of AET in males,12 and a lack of awareness regarding male breast cancer management. Although AET use increased from 2004 through 2014, overall guideline-concordant use at the end of the study period remained suboptimal.

The use of AET in men was strongly associated with treatment facility characteristics, such as academic status, and with receipt of adjuvant radiotherapy or chemotherapy. This finding suggests that men receiving multiple therapies as part of a multidisciplinary care team were more likely to receive AET, corroborating prior work that indicates increased guideline-concordant care within multidisciplinary settings.13,14 Academic facilities may be more experienced in treating male breast cancer because of an increased likelihood of seeing patients with rare diseases and may, therefore, be more likely to recommend guideline-based care with AET.

We showed a 7.2% 10-year absolute OS benefit associated with AET use. The magnitude of this benefit is the same as the 10-year OS benefit noted on the Early Breast Cancer Trialists meta-analysis comparing 5 years of adjuvant tamoxifen use with observation in female patients.3 Although we are unable to assess the length of adherence to AET in our study, it is conceivable that a considerable proportion of patients did not receive 5 years of AET based on reported premature discontinuation rates of approximately 25% in males.15 This potential medication nonadherence makes the OS benefit in our study even more impressive, and finding ways to improve the duration of medication adherence may further increase the survival benefit of AET.

Limitations

A limitation of our study is the selection bias that is inherent to retrospective studies. To minimize this bias, we performed propensity score-weighted analyses adjusting for a wide range of measured confounders. However, we were unable to account for other important factors, such as endocrine therapy type, sequence, duration of prescription and medication adherence, and toxicity that may have contributed to outcomes.

Conclusions

In summary, we showed an underuse of AET among men with HR-positive breast cancer from 2004 through 2014 despite AET use being associated with improved OS. There was also sex disparate use of AET, with a higher percentage of women than men receiving AET even though males more commonly presented with HR-positive disease. Further research on male breast cancer is warranted to optimize therapeutic strategies and to minimize disparate care.

eFigure 1. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Diagram

eFigure 2a. Percentage of Patients Receiving Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy by Year (P for trend <.001)

eFigure 2b. Hospital-Level Guideline Concordance of Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy by Year (P for trend <.001)

eFigure 3. Subgroup Analyses of Overall Survival

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics, Male Cohort (Complete Table)

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics, Male Versus Female Cohorts

eTable 3. Factors Associated With Receipt of Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy

eTable 4. Factors Associated With Overall Survival (Complete Table)

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(1):-. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korde LA, Zujewski JA, Kamin L, et al. Multidisciplinary meeting on male breast cancer: summary and research recommendations. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(12):2114-2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies C, Godwin J, Gray R, et al. ; Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) . Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):771-784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dowsett M, Forbes JF, et al. ; Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) . Aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen in early breast cancer. Lancet. 2015;386(10001):1341-1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ribeiro G, Swindell R. Adjuvant tamoxifen for male breast cancer (MBC). Br J Cancer. 1992;65(2):252-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giordano SH, Perkins GH, Broglio K, et al. Adjuvant systemic therapy for male breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104(11):2359-2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goss PE, Reid C, Pintilie M, Lim R, Miller N. Male breast carcinoma: a review of 229 patients who presented to the Princess Margaret Hospital during 40 years: 1955-1996. Cancer. 1999;85(3):629-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eggemann H, Ignatov A, Smith BJ, et al. Adjuvant therapy with tamoxifen compared to aromatase inhibitors for 257 male breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137(2):465-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American College of Surgeons. National Cancer Data Base. https://www.facs.org/quality%20programs/cancer/ncdb. Accessed November 23, 2017.

- 10.Austin PC. The performance of different propensity score methods for estimating marginal hazard ratios. Stat Med. 2013;32(16):2837-2849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bristol DR. p-value adjustments for subgroup analyses. J Biopharm Stat. 1997;7(2):313-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anelli TFM, Anelli A, Tran KN, Lebwohl DE, Borgen PI. Tamoxifen administration is associated with a high rate of treatment-limiting symptoms in male breast cancer patients. Cancer. 1994;74(1):74-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levine RA, Chawla B, Bergeron S, Wasvary H. Multidisciplinary management of colorectal cancer enhances access to multimodal therapy and compliance with National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27(11):1531-1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly SL, Jackson JE, Hickey BE, Szallasi FG, Bond CA. Multidisciplinary clinic care improves adherence to best practice in head and neck cancer. Am J Otolaryngol. 2013;34(1):57-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Visram H, Kanji F, Dent SF. Endocrine therapy for male breast cancer: rates of toxicity and adherence. Curr Oncol. 2010;17(5):17-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Diagram

eFigure 2a. Percentage of Patients Receiving Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy by Year (P for trend <.001)

eFigure 2b. Hospital-Level Guideline Concordance of Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy by Year (P for trend <.001)

eFigure 3. Subgroup Analyses of Overall Survival

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics, Male Cohort (Complete Table)

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics, Male Versus Female Cohorts

eTable 3. Factors Associated With Receipt of Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy

eTable 4. Factors Associated With Overall Survival (Complete Table)