Key Points

Question

Is formal mindfulness-based, stress-resilience training feasible for surgical interns at a tertiary academic center?

Findings

In this pilot randomized clinical trial of 21 surgical interns, an 8-week formal stress-resilience training course was found to be in demand and was practical, acceptable, and adaptable to this unique environment. The training was fully implemented and readily integrated into work and personal life by participants.

Meaning

Formal mindfulness-based stress-resilience training is feasible among academic surgery interns who find it to be acceptable and meaningful to their training experience.

Abstract

Importance

Among surgical trainees, burnout and distress are prevalent, but mindfulness has been shown to decrease the risk of depression, suicidal ideation, burnout, and overwhelming stress. In other high-stress populations, formal mindfulness training has been shown to improve mental health, yet this approach has not been tried in surgery.

Objective

To test the feasibility and acceptability of modified Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) training during surgical residency.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A pilot randomized clinical trial of modified MBSR vs an active control was conducted with 21 surgical interns in a residency training program at a tertiary academic medical center, from April 30, 2016, to December 2017.

Interventions

Weekly 2-hour, modified MBSR classes and 20 minutes of suggested daily home practice over an 8-week period.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Feasibility was assessed along 6 domains (demand, implementation, practicality, acceptability, adaptation, and integration), using focus groups, interviews, surveys, attendance, daily practice time, and subjective self-report of experience.

Results

Of the 21 residents included in the analysis, 13 were men (62%). Mean (SD [range]) age of the intervention group was 29.0 (2.4 [24-31]) years, and the mean (SD [range]) age of the control group was 27.4 (2.1 [27-33]) years. Formal stress-resilience training was feasible through cultivation of stakeholder support. Modified MBSR was acceptable as evidenced by no attrition; high attendance (12 of 96 absences [13%] in the intervention group and 11 of 72 absences [15%] in the control group); no significant difference in days per week practiced between groups; similar mean (SD) daily practice time between groups with significant differences only in week 1 (control, 28.15 [12.55] minutes; intervention, 15.47 [4.06] minutes; P = .02), week 2 (control, 23.89 [12.93] minutes; intervention, 12.61 [6.06] minutes; P = .03), and week 4 (control, 26.26 [13.12] minutes; intervention, 15.36 [6.13] minutes; P = .04); course satisfaction (based on interviews and focus group feedback); and posttraining-perceived credibility (control, 18.00 [4.24]; intervention, 20.00 [6.55]; P = .03). Mindfulness skills were integrated into personal and professional settings and the independent practice of mindfulness skills continued over 12 months of follow-up (mean days [SD] per week formal practice, 3 [1.0]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Formal MBSR training is feasible and acceptable to surgical interns at a tertiary academic center. Interns found the concepts and skills useful both personally and professionally and participation had no detrimental effect on their surgical training or patient care.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03141190

This randomized clinical trial evaluates the feasibility of formal mindfulness-based stress reduction training among surgical trainees.

Introduction

Experiencing joy in the practice of medicine is by no means guaranteed. Nonetheless, for many physicians, the unique bond with patients, the satisfaction of saving a life, and a profound sense of calling make the sacrifice and heartache worthwhile.1 In contrast, growing evidence of poor mental health and professional dissatisfaction suggests that the demands placed on many physicians are making joy and fulfillment harder to find. Mounting evidence shows that burnout, a metric for dissatisfaction and distress, is a growing problem within medicine.2 Burnout is a syndrome3 associated with worse physician performance,2,4,5 patient outcomes,6,7,8,9 and hospital economics.10,11,12 The quadruple aim of health care underscores that physician fulfillment is an important part of any sustainable reform12 and appropriately frames physician burnout and fulfillment as issues that affect everyone—not just individual clinicians.

Burnout is believed to arise from a mismatch between expectations and reality, with more than half of practicing physicians and trainees reported to experience this problem.2,13 Among general surgery residents, the prevalence of burnout is estimated at 69%14,15 and increases the odds of both overwhelming stress and distress symptoms.15 The association between overwhelming stress and burnout is concerning because extensive evidence links overwhelming stress to detrimental effects on learning, memory, decision making, and performance.16,17,18,19,20,21

A meta-analysis suggests that stress management/mindfulness interventions are effective at addressing burnout on the individual level.22 Small cohort studies and controlled trials have shown mindfulness-based interventions to be effective at reducing stress and burnout in medical students,23 primary care physicians,24 internists,25,26 and other health care professionals.27 In general surgery trainees, inherent mindfulness tendencies (shown to increase following mindfulness training),28,29 decrease the risk of burnout, overwhelming stress, and distress symptoms by 75% or more.15 This finding suggests that mindfulness tendencies may already be used, albeit unconsciously, to cope within the high-stress culture of surgery.

Mindfulness meditation training involves the cultivation of moment-to-moment awareness of thoughts, emotions, and sensations (also known as interoception),30,31 the development of nonreactivity in response to stimuli (also known as emotional regulation), and the enhancement of perspective-taking regarding oneself and others.32,33 The most scientifically studied form of mindfulness training is the secular Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn in the 1980s.34 Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction is formally offered through an 8-week, codified curriculum and has been shown to decrease stress and burnout,24,25 protect executive function,35,36 and enhance performance in multiple high-stress populations.28,37

Despite such evidence, mindfulness training among surgeons has only occasionally been suggested38 or informally pursued.39 In part, there is a seeming disconnect between surgical stoicism and indefatigability and mindfulness, which is often perceived as relaxation rather than a skill to enhance resilience. Moreover, the time pressures of surgical training make additional responsibilities and new curricula seem impossible.39,40

To systematically examine the feasibility of integrating formal mindfulness training into surgical internship at a tertiary academic center, we undertook the Mindful Surgeon pilot study. Three main questions guided our work and the findings are reported here. Is there a perceived need for formal stress-resilience training in surgery residency? Is mindfulness-based training a culturally acceptable option? Can academic surgical training accommodate the addition of a formal curriculum in mindfulness meditation without compromising training or patient care?

Methods

Settings and Participants

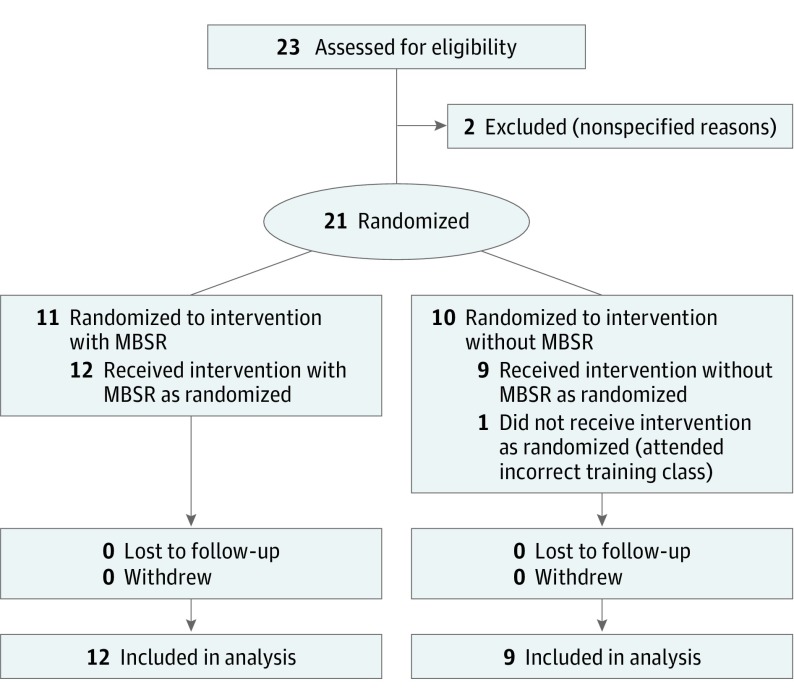

On April 30, 2016, we contacted the incoming class of surgical interns (n = 42) by email. Twenty-three categorical and preliminary interns (13 men and 10 women, drawn from general, plastic, oral-maxillofacial, urology, otolaryngology, ophthalmology, and orthopedic surgery, as well as neurosurgery) volunteered to participate in the study. A screening questionnaire was administered and reviewed for exclusion criteria (ie, previous experience with mindfulness practice, chronic inflammatory illness, current pregnancy). Two interns were withdrawn by their parent program because of class overlap with specialty-specific didactics (no remote-viewing option) and concern for compromised education. Final sample size was 21 (50%; 13 [62%] men, 8 [38%] women) (Figure). The study was completed in December 2017. The University of California, San Francisco, Institutional Review Board approved a pilot, longitudinal, randomized clinical trial to investigate the feasibility of modified MBSR for use by surgical interns. The protocol is available in Supplement 1. The participants provided written and oral informed consent; there was no financial compensation.

Figure. CONSORT Flow Diagram.

One participant randomized to the control group mistakenly attended the active intervention class and thereafter was included in that group. MBSR indicates Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction.

Intervention

Balancing for sex and subspecialty designation, we randomized participants to modified MBSR (n = 12) or an active control (n = 9) using third-party block randomization following described operationalized methods.41 We chose to use MBSR because it is secular, codified, and the most scientifically studied mindfulness-based intervention to date. The precise content of MBSR training has been described elsewhere.34 In response to the needs and concerns from trainees and leadership, some modifications to MBSR were made (Table 1). The instructor (J.M.) was formally trained in MBSR (by John Kabat-Zinn), had more than 10 000 hours of personal meditation practice, and more than 10 years of experience as an MBSR teacher. As in traditional MBSR, sessions focused on experiential training including formal (body awareness, yoga, and sitting meditation), and informal (walking meditation, transition breathing, momentary) mindfulness practices. Remaining time was filled with didactics and group activities embodying principles discussed in class. A 2- to 3-hour “mindfulness hike” replaced the traditional day-long silent retreat.

Table 1. Practical and Conceptual Modifications to Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction.

| Characteristic | Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction | Purpose of Modification | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modified | Traditional | ||

| Practical | |||

| Class No. | 8 Classes total; orientation and week 1 combined |

9 Classes total; orientation plus weeks 1-8 |

To use grand rounds summer hiatus, allow for mandatory boot-camp, but minimize missed grand rounds |

| Class duration | 2.0 h; Preserved in-class experiential time, shortened discussions and didactics, no break |

2.5 h; Emphasis on in-class experiential time, longer discussions and didactics, 10-min break |

To use natural time period of morning rounds, without violating work hours, nor infringing on education and operating room time |

| Retreat length | 2- to 3-h meditative hike in local nature preserve, offered weeks 6 and 7 | 7 h silent retreat at local meditation center, offered week 6 | To acknowledge lack of fresh air and exercise in residents’ lives and to accommodate complex days-off schedule |

| Daily formal practice time | 20 min daily | 45 min daily | To recognize minimal discretionary time in residents’ day, to respect time for other necessary personal activities but not compromise training effectiveness |

| Closure | Debrief dinner at 12-mo follow-up | Exit assessment | To preserve partial blinding of longitudinal study but still allow for feedback and reflection |

| Class size, No. | 9-12 | 15-40 | Incidental (result of enrollment) |

| Conceptual | |||

| Class content | Shorter group discussion and didactics | Meditation and relaxation 1.0-1.5 h, 10-min break, 10- to 20-min group discussion, 10- to 20-min didactics | To preserve in-class experiential component and yet respect need for shortened class duration |

| Emphasis | Building a skill set for stress resilience in medicine | Creating a tool for life-long learning about one’s self and the world, which enhances health broadly | To emphasize the necessity for explicit training to promote individual well-being in residency and future practice |

| Contextualization | Specific application of concepts and skills to professional situations (ie, mindful communication with nurses and consults, breathing techniques for operating room stress and mindful walking on rounds) | Broader application of concepts and skills to interpersonal interactions of every kind | To explicitly address the most common and recurrent sources of perceived stress in surgery and provide specific for management, and frame routines as opportunities to habitualize informal practices |

| Expectation | Daily practice is a matter of ritual and discipline; it may be partly or largely informal due to reality of daily obligations | Daily practice is hard work but gentle persistent reorientation toward a committed formal practice is the goal | To recognize the tremendous daily burden of resident obligations and to reinforce that “a little mindfulness is better than none at all” |

The active control group had similar protected class time, home practice requirements, and retreat-hike format.42,43,44 A shared reading and listening model, emphasizing external attention,45 was used in weekly discussion of articles on topics, such as perseverance, complications, honesty, and death, exploring self-care and the ethos of surgery, in each of these contexts. Daily practice comprised any self-determined self-care activity, and the retreat hike focused on the relaxing properties of nature. For both arms, multiple outcomes measures were assessed at baseline (before the start of internship), post intervention, and at 12-month follow-up.

Measuring Feasibility

To evaluate feasibility, we focused on 6 dimensions—demand, implementation, practicality, acceptability, adaptation, and integration—as proposed in a published review of feasibility studies funded through the National Cancer Institute.46 These dimensions represent a framework that can be used to comprehensively evaluate the feasibility of a given intervention. For each domain in which focus groups and key interviews were used, 2 of us (C.C.L., A.O.H., or A.D.) performed content analysis of notes and audio recordings, established categories of concepts and themes, and extracted example quotations.

Demand was operationalized as the perceived need for formalized skills to cope with stress and distress in surgical residency and evaluated by comparing stress and distress (ie, mental illness and alcohol misuse) in surgery residents with published norms from age-matched peers. Moreover, in the design phase of the Mindful Surgeon program, we held a focus group with 8 laboratory residents (after postgraduate year 3) to discuss perceptions of need, timing, and intervention content.

Implementation was operationalized as the manner in which our intervention could be fully executed within the unique culture of surgery and was evaluated by assessing interest and perceived barriers through key informant interviews with chairs and program directors from all 8 surgical departments involved in the study. Established concepts and themes served as guides for program adaptation. In addition, the study principal investigator (C.C.L.) observed weekly classes to document content delivered.

Practicality was operationalized as the costs (time and money) associated with the program and evaluated by analyzing notes from multiple strategic planning meetings with administrative, residency program, and site directors. Changes required to provide protected time for intern participation were monitored. Class attendance was taken. Frequency and duration of daily home practice were recorded via text message. Cost was evaluated by creating a cost report for personnel, space, and materials.

Acceptability was operationalized as perceived appropriateness and subjective satisfaction and evaluated with the Credibility and Expectancy Questionnaire (CEQ),45,47 which measures confidence in an intervention as a combination of cognitive credibility and affective expectancy. The CEQ comprises 6 questions rated on a scale of 0 to 10 or 0% to 100%. The first 3 questions evaluate rationale credibility and the last 3 measure treatment expectancy. Participants completed the CEQ at week 2 (after course introduction) and after week 8 (at course completion). Satisfaction was evaluated through in-class discussions and at a debriefing focus group held at study’s end.

Adaptation was operationalized as modifications made to MBSR to accommodate the unique demands and culture of surgical training and evaluated by recording changes made to traditional MBSR during planning meetings with our instructor. Meetings focused on accommodating surgery-specific scheduling and stressors while maintaining the potency of MBSR. The resultant curriculum was outlined before intervention and any changes were noted following each class.

Integration was operationalized as participant use of training skills outside of class and during follow-up and assessed by evaluating postintervention long-term practice through biweekly texts soliciting time spent and type of practices used. Both in class and during the debrief focus group, we asked for any available examples of incorporating skills personally and professionally.

Statistical Analysis

Daily practice time per week and days per week practiced were examined to evaluate the ability of interns to accommodate daily home practice and the association between effort (intervention) and practice frequency and magnitude. Data are reported as group means (SD), comparing the number of days and time per day for each week of the study. Differences between groups at each week were evaluated by 2-sample, independent t tests, and P values were calculated with α level set at <.05. All calculations were done using Excel 2016 (Microsoft Inc).

Results

Participants

The intervention group (n = 12), aged 24 to 31 years, included 5 women (42%). The control group (n = 9), aged 27 to 33 years, included 3 women (33%) (Table 2).

Table 2. Characteristics of Study Sample.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention (n = 12) | Control (n = 9) | |

| Demographics | ||

| Sex | ||

| Male | 7 (58) | 6 (67) |

| Female | 5 (42) | 3 (33) |

| Race | ||

| White | 7 (58) | 4 (44 |

| Black | 0 | 1 (11) |

| Asian | 5 (42) | 4 (44) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 29.0 (2.4) | 27.4 (2.1) |

| Subspecialty | ||

| General surgery | ||

| Categorical | 4 (33) | 1 (11) |

| Preliminary | 1 (8) | 1 (11) |

| Urology | 1 (8) | 1 (11) |

| Otolaryngology | 1 (8) | 1 (11) |

| Neurosurgery | 1 (8) | 0 |

| OMFS | 1 (8) | 2 (22) |

| Plastics | 1 (8) | 1 (11) |

| Ophthalmology | 1 (8) | 1 (11) |

| Orthopedics | 1 (8) | 1 (11) |

Abbreviation: OMFS, oral and maxillofacial surgery.

Feasibility Outcomes

Demand

Local and national surveys demonstrate 2 to 5 times higher burnout, stress, and distress symptoms in surgery residents than in the general population.15 Focus group discussion revealed a perceived need for stress-resilience training during surgical residency. Content analysis of quotations revealed recurrent themes of anger as a culturally encouraged coping strategy, the experience of highly distressing affective and behavioral changes, and an early experience of disillusionment in the absence of adequate coping skills (Table 3).

Table 3. Example Quotations: Demand and Implementation.

| Focus Group: Anger and Disillusionmenta | Key Informant Interviews: Perceived Need and Barriersb |

|---|---|

| “Right now we use anger as a coping mechanism. It’s a very temporary fix, it ultimately doesn’t help anyone. I think that anger and shortness are learned behaviors—learned culturally…in surgery.” | “We know we’re delivering excellent surgeons, but I worry that they are (not nice people)…” |

| “You notice that you start responding to the same stresses differently than you used to. You don’t necessarily like the person you’re becoming. For example, the ED calls you and you are immediately mad at them. And they haven’t done anything half of the time. And then you look back and you say: “That’s not who I am; I don’t want to be that way.” | “I see it; the change in them. I've watched so many come through. They start bright-eyed and helpful, then something happens. It's in the third year, their eyes get dull.” |

| “You feel like such a rock star when you get accepted into surgical residency, but 6 mo into your intern year, you realize how hard this is, how much you don’t know, and that you signed up for 7 more years of this.” | “Any off-service activity for the study interns should be scheduled when they have no service obligations and their absence won't be noticed. I'm not sure when that would be, maybe never.” |

Abbreviation: ED, emergency department.

Focus group consisted of 8 laboratory residents (after postgraduate year 3).

Key informant interviews were conducted by the principal investigator with chairs and program directors from all 8 surgical departments contributing interns to the study.

Implementation

Key informant interviews with 5 program directors and 4 surgery chairs revealed uniform recognition of high burnout and distress among residents and variable interest in intervention. Themes included concern for diminished professionalism and resident well-being, the need for dissemination of evidence supporting MBSR, and trepidation regarding costs related to protected time (Table 3). Although recognition of need was universal, the perceived challenges of scheduling, disrupted patient care, and value kept several departments from full participation. In response to these perceived hurdles, specific scheduling and coverage concerns were elicited from directors, administrators, and chiefs and were specifically addressed in strategic planning meetings. Regarding value, grand rounds laden with evidence of MBSR efficacy48 and feasibility (particularly in the military)49 were widely presented. No adverse patient events were reported in association with study participation. No classes were cancelled or truncated and all parts of the planned curriculum were delivered.

Practicality

Through strategic planning, we capitalized on weekly time established for surgical education (per American College of Graduate Medical Education standards), which is also the day for late-start operations and grand rounds at our institution. As such, class did not affect operative experience, but precluded participants from attending morning rounds. Coordinating coverage with service chiefs and minimizing adjacent nightshifts made protected time possible. Twice, on services with 1 intern in a critical role, moonlighters were used for coverage. Regarding grand rounds, an established 8-week summer hiatus was used for 3 intern boot-camp sessions followed by 5 weeks of class. The remaining 3 weeks of class overlapped with grand rounds, which were made available online for trial participants to view at their convenience.

There was no attrition from the control or intervention group. Absences, 12 of 96 (13%) in the intervention group and 11 of 72 (15%) in the control group, were primarily due to service commitments (unstable patient status), previously scheduled vacations, or personal emergencies, with 1 absence in each group due to oversleeping. Nine participants (75%) from the intervention group and 4 individuals (44%) from the control group attended the voluntary retreat hike. Control participants had statistically significant longer daily practice time than the intervention group during 3 weeks and no significant difference in days per week of practice. Otherwise, both groups practiced similar duration and frequency on a weekly basis (eTable in Supplement 2).

Monetary costs consisted of an MBSR instructor and course materials ($4300); use of a moonlighter twice, for 2 hours (total, $400); and course materials, which included yoga mats and continental breakfast ($20/participant total). A room on campus was provided without charge.

Acceptability

Participants indicated similar levels of treatment expectancy and rationale credibility, as assessed by the CEQ. At week 2, expectancy was 10.28 (7.05) and 14.33 (4.21) (P = .18) and credibility was 17.28 (6.49) and 18.92 (4.87) (P = .53), respectively, for the control and intervention groups. Week 8 expectancy was 11.78 (6.00) and 18.21 (6.19) (P = .41) and credibility was 18.00 (4.24) and 20.00 (6.55) (P = .03, respectively).

Intervention participant comments during class and at the debriefing focus group revealed an overall high level of satisfaction (Table 4). Themes included greater self-awareness and self-regulation, enhanced focus in the operating room or on-service, and improved interactions with patients and colleagues.

Table 4. Example Quotations: Satisfaction and Integration.

| In Class Reflectiona | Debrief Focus Groupb |

|---|---|

| Intervention Participants | |

| “I thought I would be learning a relaxation technique, but it is not relaxation. I didn't believe in this when you first explained it. I thought it was sort of ridiculous, but it has changed me. Practicing is work, but feels like a gift to myself, not like work at all. It is way more than relaxing—it's changed how I think, how I see things, how things affect me. Before I go into the OR to speak to the chief, especially if I have to say something that I know will upset him, I breath and focus and I am clearer, explain better, am not nervous.” | “Once I learned how to access ‘being in the moment,’ I started using this in the OR through an awareness of my body: realizing I was holding my breath, clenching my stomach, and I would just breathe. It brought everything back into focus. Now I try to do this every time.” |

| “I am being more purposeful and present with patients, families, and work. I wrote orders to pronounce a 32-year-old dead. I was able to be in that experience, with them, and be okay.” | “I loved learning mindful communication. This was so useful. Realizing I don’t need to confront people or fight with them over anything really. Dropping it and moving on becomes so easy and light.” |

| “I can't believe how rich life is. It's amazing I didn't see this before; like I was living in the fog. I use these techniques…when I'm walking the halls in the hospital. I am more patient and present with the med students. It affects how I interact with patients. For some of the miserable ones, I share what I’ve learned [in class].” | “I learned how to control my heart rate. I would monitor it with my watch. Then I realized that I could do this when I was stressed and I would become calm.” |

| “Mindfulness has changed how I approach pages. I recognize that my reaction is just an emotion and not the reality. Twenty percent of the time that works, and it’s getting even better.” | “I use the breathing everywhere: scrubbing into the OR, stepping off the elevator, when I first get in my car at the end of the day. It resets everything and I can focus.” |

| Control Participants | |

| “I’ve only been an intern two months and already had patients die. I know it affects me, that I care, but it gets harder to feel it. I don’t know where that goes.” | “Having an established group to check-in with, especially in those first months was really great. It didn’t feel like we were getting skills exactly, but it felt like a community.” |

| “It’s helpful to have the assignment of self-care every day—makes it easier to do something that probably I should do all the time, anyway.” | “It gave me friends outside my (primary program) cohort. More comrades throughout the hospitals. I’d walk out of a hard encounter and I’d see [a classmate]. One code-word [from the readings] and they got it.” |

| “I really like this discussion (about patients with chronic illness and feelings of frustration and fatigue). I’ve been on [X service] and we see patients like this a lot. It’s hard to sympathize sometimes; sometimes they’re so mean. I’m like, “What about me? I’m just trying to help you!” It makes me not like them—which seems less embarrassing to admit now.” | “Dr X (the control class instructor) was so great. I came for him, because he cared about us so much. He obviously thought a lot about these articles and the discussions and really cared about us being strong and taking care of ourselves. He cared about us as individuals. My [nonstudy] cohort didn’t have that and I think it makes a difference.” |

Abbreviation: OR, operating room.

In-class reflections of 12 intervention participants were solicited by intervention instructor at weeks 4 and 8.

Debrief focus group with 8 intervention participants was held with the principal investigator following 12-month assessment.

Adaptation and Integration

The original MBSR program format was modified, practically and conceptually, to accommodate the concerns of residents, program directors, and chairs revealed during the planning phases of the study (Table 1). On a daily basis, participants used informal practices (eg, mindful walking, scrubbing, eating, or short breathing exercises) with greater frequency than formal practice (eg, sitting meditation or body scan) at work and at home (Table 4). Practice was variably maintained a mean of 3 (.0) days per week in the follow-up year. Practice times ranged from 5 to 20 minutes, longitudinally, but 5 of 12 participants (42%) occasionally meditated for 45 minutes on days off.

Discussion

This pilot randomized clinical trial demonstrates that formal mindfulness-based training is feasible and acceptable for surgical interns at a tertiary academic medical center. To address burnout and distress in medicine, institutional change is necessary. Nonetheless, such changes will take time to identify and creativity to implement. Meanwhile, individual resilience training can mitigate overwhelming stress and enhance clinicians’ ability to guide these changes.50 As with any fundamental skill-set, early nurturing increases lasting effect, yet the question remains: Why bother? It would be easier to provide a mindfulness smartphone app or an online course. To our knowledge, there has been only 1 randomized clinical trial to date comparing formal mindfulness training with a smartphone app.51 Findings suggest that smartphone apps may transiently increase self-compassion, but formal training affects perceived stress and burnout. These findings concur with those from studies of online mindfulness training, which have not been found to be as effective as formal, in-person, training.39 In line with this outcome, deeper examination of the mechanisms of mindfulness training suggests that the good feelings cultivated by popularized attention training are only a fraction of what mindfulness can deliver.52,53,54 The more complex skills of interoception, emotional regulation, and perspective taking, typically taught through formal training, appear to yield neurologic and cognitive changes that can enhance compassion, self-regulation, executive function, and performance.32,52,54 If these results occur, then the value of investing in formal mindfulness training is obvious. Nevertheless, before we can test for such benefits among surgeons, formal training must be deemed feasible. Our pilot study shows it to be so.

Our first finding, that demand for formal stress-resilience training exists within surgery, is supported by national data showing higher burnout, stress, and distress in general surgery trainees compared with age-matched peers. Moreover, at our institution, focus group and key interview content analysis revealed recurrent themes and concepts indicating undesirable affective and behavioral changes during residency and the desire for training to mitigate this process. Evidence supporting the value of formal cognitive training to enhance psychological well-being and/or performance comes from the military,54,55 professional sports,56,57 and, more recently, surgery.58 Although training and practice are central pillars of surgery, the explicit desire for cognitive skills training is arguably new, and therefore worth demonstrating.

Our second finding that formal mindfulness-based training is feasible during surgical internship is supported by the reasonable cost and high attendance, satisfaction, rate of home practice, and degree of integration by participants. These results reflect both the participants’ positive experience and extensive preparatory work. Building consensus and collaboration allowed us to capitalize on established infrastructure (eg, education days, late-start operations, and coverage by midlevel clinicians), which minimized conflicts and made protected participation possible.

Our third and perhaps most significant finding is that MBSR was satisfying for surgical interns, as evidenced by high attendance, committed daily practice, and subjective satisfaction. Although the control group mean daily practice time was significantly higher during 3 early weeks of the course, it is worth noting that mindfulness practice is effortful,52 but control practice was relaxation. Despite the effort required, the intervention group was not deterred from practicing, even if the mean duration of daily practice was occasionally shorter. In addition, perceived logical credibility was not significantly different between groups before or after the intervention, but the expectation of efficacy was significantly higher for the intervention group at training’s end. This finding suggests that, although the control practice may have been relaxing and enjoyable, stress resilience may not have been a perceived byproduct, whereas it was in the effortful intervention.

Our fourth finding, that mindfulness skills can be effectively integrated into surgical training, is supported by the extent to which interns used mindfulness skills independently during the course and thereafter. Despite the apparent discord between conservative surgical culture and mindfulness meditation, participants expressed gratitude for the skills that they acquired and remarked how training changed their ability to manage the high-stress aspects of residency—both personal and professional. In addition, without external encouragement or incentive, participants continued to use both the formal and informal skills during the following year, suggesting that the creation of enduring healthy habits is possible.

Limitations

This study has limitations, most notably the small sample comprising volunteers at a single institution with its unique issues and resources. However, our goal was to demonstrate feasibility and identify the resources and organizational factors required. Further work remains to obtain statistical power, expand to other specialties, and compare the efficacy of formal training with easier interventions with other formats, such as smartphone apps and online modules.

Conclusions

Although the value of formal mindfulness training has been established in other settings and populations, it remains unproven in surgery. Nevertheless, there is a growing body of literature regarding the need and desire for institutionally supported, individually focused interventions to address stress and burnout, and mindfulness-based interventions are promising in this regard.10,22,25,59Although the efficacy of formal mindfulness training remains to be proven in surgery, our study demonstrates that the necessary foundations of feasibility and acceptability are in place. With this in mind, we may find that the latest American College of Graduate Medical Education requirement for specific programming to improve resident well-being is a challenge that we can meet.

Protocol

eTable. Mean Daily Practice Time and Mean Practice Days per Week

References

- 1.Zwack J, Schweitzer J. If every fifth physician is affected by burnout, what about the other four? resilience strategies of experienced physicians. Acad Med. 2013;88(3):-. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318281696b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balch CM, Copeland E. Stress and burnout among surgical oncologists: a call for personal wellness and a supportive workplace environment. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(11):3029-3032. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9588-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheepers RA, Boerebach BC, Arah OA, Heineman MJ, Lombarts KM. A systematic review of the impact of physicians’ occupational well-being on the quality of patient care. Int J Behav Med. 2015;22(6):683-698. doi: 10.1007/s12529-015-9473-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haas JS, Cook EF, Puopolo AL, Burstin HR, Cleary PD, Brennan TA. Is the professional satisfaction of general internists associated with patient satisfaction? J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(2):122-128. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.02219.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DiMatteo MR, Sherbourne CD, Hays RD, et al. Physicians’ characteristics influence patients’ adherence to medical treatment: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Health Psychol. 1993;12(2):93-102. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.12.2.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Del Canale S, Louis DZ, Maio V, et al. The relationship between physician empathy and disease complications: an empirical study of primary care physicians and their diabetic patients in Parma, Italy. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1243-1249. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182628fbf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinsky CA, Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Tutty M, Shanafelt TD. Professional satisfaction and the career plans of US physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(11):1625-1635. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dyrbye LN, Trockel M, Frank E, et al. Development of a research agenda to identify evidence-based strategies to improve physician wellness and reduce burnout. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(10):743-744. doi: 10.7326/M16-2956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shirley ED, Sanders JO. Patient satisfaction: Implications and predictors of success. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(10):e69. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-576. doi: 10.1370/afm.1713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell J, Prochazka AV, Yamashita T, Gopal R. Predictors of persistent burnout in internal medicine residents: a prospective cohort study. Acad Med. 2010;85(10):1630-1634. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181f0c4e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elmore LC, Jeffe DB, Jin L, Awad MM, Turnbull IR. National survey of burnout among US general surgery residents. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223(3):440-451. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lebares CC, Guvva EV, Ascher NL, O’Sullivan PS, Harris HW, Epel ES. Burnout and stress among US surgery residents: psychological distress and resilience. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(1):80-90. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liston C, McEwen BS, Casey BJ. Psychosocial stress reversibly disrupts prefrontal processing and attentional control. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(3):912-917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807041106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karlamangla AS, Singer BH, McEwen BS, Rowe JW, Seeman TE. Allostatic load as a predictor of functional decline. MacArthur studies of successful aging. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(7):696-710. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00399-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McEwen BS. In pursuit of resilience: stress, epigenetics, and brain plasticity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016;1373(1):56-64. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eskildsen A, Andersen LP, Pedersen AD, Vandborg SK, Andersen JH. Work-related stress is associated with impaired neuropsychological test performance: a clinical cross-sectional study. Stress. 2015;18(2):198-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arora S, Sevdalis N, Aggarwal R, Sirimanna P, Darzi A, Kneebone R. Stress impairs psychomotor performance in novice laparoscopic surgeons. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(10):2588-2593. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1013-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wetzel CM, Kneebone RL, Woloshynowych M, et al. The effects of stress on surgical performance. Am J Surg. 2006;191(1):5-10. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.08.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-2281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Dijk N, Hooft L, Wieringa-de Waard M. What are the barriers to residents’ practicing evidence-based medicine? a systematic review. Acad Med. 2010;85(7):1163-1170. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d4152f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, et al. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1284-1293. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527-533. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amutio A, Martínez-Taboada C, Delgado LC, Hermosilla D, Mozaz MJ. Acceptability and effectiveness of a long-term educational intervention to reduce physicians’ stress-related conditions. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2015;35(4):255-260. doi: 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lo K, Waterland J, Todd P, et al. Group interventions to promote mental health in health professional education: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2018;23(2):413-447. doi: 10.1007/s10459-017-9770-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flook L, Goldberg SB, Pinger L, Bonus K, Davidson RJ. Mindfulness for teachers: a pilot study to assess effects on stress, burnout and teaching efficacy. Mind Brain Educ. 2013;7(3):182-195. doi: 10.1111/mbe.12026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobs TL, Epel ES, Lin J, et al. Intensive meditation training, immune cell telomerase activity, and psychological mediators. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(5):664-681. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kok BE, Singer T. Phenomenological fingerprints of four meditations: differential state changes in affect, mind-wandering, meta-cognition, and interoception before and after daily practice across 9 months of training. Mindfulness (N Y). 2017;8(1):218-231. doi: 10.1007/s12671-016-0594-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson DC, Thom NJ, Stanley EA, et al. Modifying resilience mechanisms in at-risk individuals: a controlled study of mindfulness training in Marines preparing for deployment. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(8):844-853. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13040502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hölzel BK, Lazar SW, Gard T, Schuman-Olivier Z, Vago DR, Ott U. How does mindfulness meditation work? proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6(6):537-559. doi: 10.1177/1745691611419671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ricard M, Lutz A, Davidson RJ. Mind of the meditator. Sci Am. 2014;311(5):38-45. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1114-38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kabat-Zinn J. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness New York: Bantam Books; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jha AP, Stanley EA, Kiyonaga A, Wong L, Gelfand L. Examining the protective effects of mindfulness training on working memory capacity and affective experience. Emotion. 2010;10(1):54-64. doi: 10.1037/a0018438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: a meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57(1):35-43. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seppälä EM, Nitschke JB, Tudorascu DL, et al. Breathing-based meditation decreases posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in US military veterans: a randomized controlled longitudinal study. J Trauma Stress. 2014;27(4):397-405. doi: 10.1002/jts.21936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fernando A, Consedine N, Hill AG. Mindfulness for surgeons. ANZ J Surg. 2014;84(10):722-724. doi: 10.1111/ans.12695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldhagen BE, Kingsolver K, Stinnett SS, Rosdahl JA. Stress and burnout in residents: impact of mindfulness-based resilience training. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015;6:525-532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ames SE, Cowan JB, Kenter K, Emery S, Halsey D. Burnout in orthopaedic surgeons: a challenge for leaders, learners and colleagues: AOA critical issues. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(14):e78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parker MJ, Manan A, Duffett M. Rapid, easy, and cheap randomization: prospective evaluation in a study cohort. Trials. 2012;13:90. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Finucane A, Mercer SW. An exploratory mixed methods study of the acceptability and effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for patients with active depression and anxiety in primary care. BMC Psychiatry. 2006;6:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-6-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MacCoon DG, Imel ZE, Rosenkranz MA, et al. The validation of an active control intervention for Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). Behav Res Ther. 2012;50(1):3-12. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davidson RJ, Kaszniak AW. Conceptual and methodological issues in research on mindfulness and meditation. Am Psychol. 2015;70(7):581-592. doi: 10.1037/a0039512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allen M, Dietz M, Blair KS, et al. Cognitive-affective neural plasticity following active-controlled mindfulness intervention. J Neurosci. 2012;32(44):15601-15610. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2957-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bowen DJ, Kreuter M, Spring B, et al. How we design feasibility studies. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(5):452-457. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Devilly GJ, Borkovec TD. Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2000;31(2):73-86. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7916(00)00012-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hölzel BK, Carmody J, Evans KC, et al. Stress reduction correlates with structural changes in the amygdala. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2010;5(1):11-17. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cornum R, Matthews MD, Seligman ME. Comprehensive soldier fitness: building resilience in a challenging institutional context. Am Psychol. 2011;66(1):4-9. doi: 10.1037/a0021420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kok BE, Singer T. Effects of contemplative dyads on engagement and perceived social connectedness over 9 months of mental training: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(2):126-134. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mistretta EG, Davis MC, Temkit M, Lorenz C, Darby B, Stonnington CM. Resilience training for work-related stress among health care workers: results of a randomized clinical trial comparing in-person and smartphone-delivered interventions. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60(6):559-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tang YY, Hölzel BK, Posner MI. The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(4):213-225. doi: 10.1038/nrn3916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rahl HA, Lindsay EK, Pacilio LE, Brown KW, Creswell JD. Brief mindfulness meditation training reduces mind wandering: the critical role of acceptance. Emotion. 2017;17(2):224-230. doi: 10.1037/emo0000250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lindsay EK, Young S, Smyth JM, Brown KW, Creswell JD. Acceptance lowers stress reactivity: dismantling mindfulness training in a randomized controlled trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;87:63-73. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deuster PA, OʼConnor FG. Human performance optimization: culture change and paradigm shift. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29(11)(suppl 11):S52-S56. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000001118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deuster PA, Schoomaker E. Mindfulness: a fundamental skill for performance sustainment and enhancement. J Spec Oper Med. 2015;15(1):93-99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wagstaff CR. Emotion regulation and sport performance. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2014;36(4):401-412. doi: 10.1123/jsep.2013-0257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stefanidis D, Anton NE, Howley LD, et al. Effectiveness of a comprehensive mental skills curriculum in enhancing surgical performance: results of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Surg. 2017;213(2):318-324. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):195-205. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Protocol

eTable. Mean Daily Practice Time and Mean Practice Days per Week