Key Points

Question

What are risk factors for suicide attempt among US Army soldiers with no history of mental health diagnosis?

Findings

This longitudinal cohort study of 9650 enlisted soldiers with a documented suicide attempt and 153 528 control person-months found no history of mental health diagnosis in more than one-third of those who attempted suicide. Risk factors for attempt (sociodemographic, service related, physical health care, injury, subjection to crime, crime perpetration, and family violence) were similar regardless of previous diagnosis, although the strength of associations differed.

Meaning

This study suggests that personnel, medical, legal, and family services records may assist in identifying suicide attempt risk among soldiers with unrecognized mental health problems.

This longitudinal cohort study examines risk factors associated with attempted suicide among soldiers without a previous mental health diagnosis using administrative data from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers.

Abstract

Importance

The US Army suicide attempt rate increased sharply during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Although soldiers with a prior mental health diagnosis (MH-Dx) are known to be at risk, little is known about risk among those with no history of diagnosis.

Objective

To examine risk factors for suicide attempt among soldiers without a previous MH-Dx.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this retrospective longitudinal cohort study using administrative data from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS), person-month records were identified for all active-duty Regular Army enlisted soldiers who had a medically documented suicide attempt from January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2009 (n = 9650), and an equal-probability sample of control person-months (n = 153 528). Data analysis in our study was from September 16, 2017, to June 6, 2018. In a stratified sample, it was examined whether risk factors for suicide attempt varied by history of MH-Dx.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Suicide attempts were identified using Department of Defense Suicide Event Report records and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification E95 × diagnostic codes. Mental health diagnoses and related codes, as well as sociodemographic, service-related, physical health care, injury, subjection to crime, crime perpetration, and family violence variables, were constructed from Army personnel, medical, legal, and family services records.

Results

Among 9650 enlisted soldiers with a documented suicide attempt (74.8% male), 3507 (36.3%) did not have a previous MH-Dx. Among soldiers with no previous diagnosis, the highest adjusted odds of suicide attempt were for the following: female sex (odds ratio [OR], 2.6; 95% CI, 2.4-2.8), less than high school education (OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.8-2.0), first year of service (OR, 6.0; 95% CI, 4.7-7.7), previously deployed (OR, 2.4; 95% CI, 2.1-2.8), promotion delayed 2 months or less (OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.7-2.6), past-year demotion (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.3-1.8), 8 or more outpatient physical health care visits in the past 2 months (OR, 3.3; 95% CI, 2.9-3.8), past-month injury-related outpatient (OR, 3.0; 95% CI, 2.8-3.3) and inpatient (OR, 3.8; 95% CI, 2.3-6.3) health care visits, previous combat injury (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.0-2.4), subjection to minor violent crime (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.1-2.4), major violent crime perpetration (OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3-3.0), and family violence (OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.9-4.4). Most of these variables were also associated with suicide attempts among soldiers with a previous MH-Dx, although the strength of associations differed.

Conclusions and Relevance

Suicide attempt risk among soldiers with unrecognized mental health problems is a significant and important challenge. Administrative records from personnel, medical, legal, and family services systems can assist in identifying soldiers at risk.

Introduction

Rates of suicidal behavior in the US Army increased during the Afghanistan and Iraq wars.1,2,3 Among soldiers, as in the general population,4,5,6,7,8 mental disorders are consistent predictors of suicide attempt9,10,11,12,13 and death.3,14 However, only 60% of enlisted soldiers with a documented suicide attempt10 and less than 50% of soldiers who died by suicide3 actually received a prior mental health diagnosis (MH-Dx). Understanding risk in those outside the mental health care system15,16 is important for addressing the 40% of suicide attempts that occur among enlisted soldiers with no MH-Dx history.10 Risk factors for veteran suicide differ for those with and without documented psychiatric symptoms,15 but it is not known whether suicide attempt predictors in active-duty soldiers9,10 differ for those with and without an MH-Dx. Suicide attempts are more likely among enlisted soldiers who are female, younger, non-Hispanic white, less educated, in their first tour of duty (particularly the first 2 years of service), and never or previously deployed (vs currently deployed).10 Combat arms and combat medic occupations have elevated risk, whereas special forces soldiers have lower risk.16 Although findings are mixed regarding the association of marital status with military suicidal behaviors,2,10,11 recency of marriage beginning or ending may provide information about risk during marital transitions.17,18,19

Medical, legal, and family services records might help identify those at risk. Most civilians who die by suicide have contact with primary care providers in the year before death.20 Similarly, service members show high rates of outpatient health care use, frequently primary care, in the month before suicide or intentionally self-inflicted injury.21 Almost 97% of soldiers who died by suicide during 2004 to 2009 had a past-year non–mental health encounter, and almost 38% had a past-month encounter.22 Treatment for injuries may be particularly important.23 Recent injury-related hospitalization, including unintentional injury, predicts suicide among soldiers.24 Legal and family services encounters also provide opportunities because being subjected to crime, perpetrating crime,25,26,27,28,29 and family violence are associated with suicide risk.29,30,31,32,33,34 Using administrative data from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS),35 we examined a wide range of suicide attempt predictors among active-duty Regular Army enlisted soldiers with and without previous MH-Dx and the extent to which predictors differed by MH-Dx history.

Methods

Sample

This retrospective longitudinal cohort study used data from the Army STARRS Historical Administrative Data Study, which integrates 38 Army and Department of Defense (DoD) administrative data systems, including every system in which suicidal events are documented. The Historical Administrative Data Study includes individual-level person-month records for all soldiers on active duty from January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2009 (1.66 million soldiers).36 Data analysis in our study was from September 16, 2017, to June 6, 2018. This component of Army STARRS was approved by the institutional review boards of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (Bethesda, Maryland), Harvard Medical School (Boston, Massachusetts), University of Michigan Institute for Social Research (Ann Arbor), and University of California San Diego (La Jolla), which determined that the study did not constitute human participant research because it relied on deidentified secondary data; therefore, informed consent was not obtained.

The analytic sample was 9650 Regular Army enlisted soldiers who attempted suicide from 2004 through 2009 (excluding Army National Guard and Reserve), plus an equal-probability sample of 153 528 control person-months. Data were analyzed using a discrete-time survival framework with person-month as the unit of analysis.37 We reduced computational intensity by selecting an equal-probability 1:200 sample of control person-months stratified by sex, rank, time in service, deployment status (never, currently, or previously deployed), and historical time. Control person-months excluded all soldiers with a documented suicide attempt or other nonfatal suicidal event (eg, suicide ideation)1 and person-months in which a soldier died. Each control person-month was assigned a weight of 200 to adjust for undersampling.

Measures

Suicide Attempts

Soldiers who attempted suicide were identified using administrative records from the Department of Defense Suicide Event Report,38 a DoD-wide surveillance mechanism aggregating suicidal behavior information via a standardized form completed by medical providers, and from International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) E950 to E958 codes (self-inflicted poisoning or injury with suicidal intent) associated with health care encounters from military and civilian treatment facilities, combat operations, and aeromedical evacuations (eTable 1 in the Supplement). For soldiers with multiple suicide attempts, we selected the first attempt using a hierarchical classification scheme.1

Sociodemographic and Service-Related Characteristics

Administrative records were used for sociodemographic variables (sex, current age, race/ethnicity, education, and marital status) and service-related variables (age at Army entry, time in service, deployment status [never, currently, or previously], delayed promotion, demotion, and military occupation [combat arms, special forces, combat medic, or other]) (eTable 2 in the Supplement). We also calculated recency of marriage starting or ending (ie, divorced or widowed).

MH-Dx and Related Codes

Administrative medical records identified previous MH-Dx during Army service. The indicator variable combined all ICD-9-CM mental health diagnostic codes and mental health–related V codes (eg, stressors/adversities and marital problems), excluding postconcussion syndrome and tobacco use disorder (eTable 3 in the Supplement). This definition of MH-Dx detected all soldiers with and without documented, clinically significant mental health difficulties. In most cases, absence of MH-Dx indicates that significant symptoms were not reported or detected during routine medical care. It does not signify thorough assessment of mental disorders.

Physical Health Care Visits and Injuries

Administrative medical records identified number of days with an outpatient physical health care (OP-physical) visit in the previous 2 months, presence and recency of outpatient and inpatient visits for previous injury (OP-injury and IP-injury), and previous combat injury–related visits. Injury-related health care visits were identified using ICD-9-CM codes 800 to 999, codes in the 700s indicating musculoskeletal injuries,39 supplemental E codes, and injury and trauma codes from the 2050 North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Standardization Agreement.40 Administrative records suggest that these previous injuries were nonsuicidal.

Crime and Family Violence

We examined legal records indicating soldiers who were subjected to or perpetrated founded crimes for which the Army had sufficient evidence to warrant investigation (eTable 4 in the Supplement). Subjects of crime and perpetrators were hierarchically categorized by crime severity (major violent, minor violent, or nonviolent). We constructed a variable indicating whether soldiers were subjected to and/or perpetrated documented family violence (eg, physical, sexual, or emotional abuse of spouse or child) using legal records, the Army Central Registry (a family services data system capturing family violence–related events), and medical (ICD-9-CM) records (eTable 5 and eTable 6 in the Supplement), with details reported elsewhere.31 Consistent with previous work,31 the family violence indicator included founded or unfounded legal events and substantiated or unsubstantiated Army Central Registry events.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted using a statistical software program (SAS, version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc).41 After examining the association of MH-Dx history with suicide attempt in univariable and multivariable logistic regression models, the sample was stratified by soldiers with and without previous MH-Dx. Within each group, logistic regression analyses examined multivariable associations of sociodemographic and service-related characteristics with suicide attempt, followed by separate models evaluating incremental predictive associations of marriage start/end recency (replacing marital status in those models), physical health care use, injury, subjection to crime, crime perpetration, and family violence. Interactions were examined in separate multivariable models (adjusting for sociodemographic and service-related variables) to identify whether associations differed by MH-Dx history. Logistic regression coefficients were exponentiated to obtain odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs. Final model coefficients were used to generate a standardized risk estimate42 (ie, number of soldiers with an suicide attempt per 100 000 person-years) for each predictor category under the model assuming that other predictors were at their samplewide means. Because the suicide attempt rate increased during the Afghanistan and Iraq wars,1 each logistic regression equation controlled for calendar month and year. Coefficients of other predictors can consequently be interpreted as averaged within-month associations based on the assumption that associations of other predictors do not vary over time. Significance was evaluated using 2-sided tests and set at P < .05.

Results

Most of the weighted sample was male (86.3% [26 507 814 person-months]), younger than 30 years (68.4% [20 975 370 person-months]), of non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity (59.8% [18 358 008 person-months]), high school educated (76.5% [23 503 980 person-months]), and currently married (54.7% [16 814 774 person-months]) (eTable 7 in the Supplement). Among 9650 enlisted soldiers with a documented suicide attempt (74.8% male), more than one-third (3507 [36.3%]) had no previous MH-Dx. An MH-Dx history was associated with higher odds of suicide attempt (OR, 3.2; 95% CI, 3.1-3.3), which persisted after adjusting for sociodemographic and service-related variables (OR, 6.2; 95% CI, 5.9-6.5) (eTable 7 in the Supplement). When stratified by MH-Dx history, significant sociodemographic and service-related predictors were generally similar. In both groups, odds of suicide attempt were higher among soldiers who were female, younger, non-Hispanic white, less educated, in their first 4 years of service, never or previously deployed, and those with a delayed promotion, demotion, and combat arms or combat medic occupation. Associations of sex, education, age at Army entry, time in service, delayed promotion, demotion, and military occupation with suicide attempt differed by MH-Dx status (Table 1). Pairwise analyses found that ORs were generally larger among those with no previous MH-Dx. Female sex, less than high school education, delayed promotion, and past-year demotion increased odds of suicide attempt in both groups but significantly more so in soldiers without previous MH-Dx. Entering the Army before age 21 years was associated with suicide attempt in those without but not with MH-Dx history. While ORs were generally higher among soldiers with no previous MH-Dx, their standardized risk of suicide attempt was consistently lower in each predictor category (Table 1).

Table 1. Multivariable Associations of Sociodemographic and Service-Related Variables With Suicide Attempt Among Regular Army Enlisted Soldiers With and Without a History of Mental Health Diagnosisa.

| Variable | No Previous Mental Health Diagnosis (n = 103 525) | Any Previous Mental Health Diagnosis (n = 59 653) | Predictor by Mental Health Historyb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | SREc | OR (95% CI) | SREc | ||

| Sociodemographic Predictors | |||||

| Sex | χ21 = 128.1; P < .001 | ||||

| Male | 1 [Reference] | 177 | 1 [Reference] | 637 | |

| Female | 2.6 (2.4-2.8) | 459 | 1.4 (1.3-1.5) | 907 | |

| Statistics | χ21 = 502.4; P < .001 | χ21 = 118.3; P < .001 | |||

| Current age | χ25 = 1.1; P = .95 | ||||

| <21 | 1.4 (1.1-1.9) | 246 | 1.7 (1.5-2.1) | 984 | |

| 21-24 | 1.1 (0.9-1.5) | 191 | 1.4 (1.2-1.6) | 729 | |

| 25-29 | 1.1 (0.9-1.3) | 180 | 1.1 (1.0-1.2) | 583 | |

| 30-34 | 1 [Reference] | 169 | 1 [Reference] | 524 | |

| 35-39 | 0.9 (0.7-1.3) | 160 | 0.8 (0.7-1.0) | 433 | |

| ≥40 | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) | 150 | 0.8 (0.6-1.0) | 430 | |

| Statistics | χ25 = 16.8; P = .005 | χ25 = 61.8; P < .001 | |||

| Race/ethnicity | χ24 = 4.6; P = .33 | ||||

| White | 1 [Reference] | 229 | 1 [Reference] | 747 | |

| Black | 0.7 (0.7-0.8) | 164 | 0.7 (0.7-0.8) | 540 | |

| Hispanic | 0.8 (0.8-0.9) | 191 | 0.8 (0.8-0.9) | 620 | |

| Asian | 0.8 (0.6-0.9) | 220 | 0.8 (0.7-1.0) | 725 | |

| Other | 1.0 (0.7-1.3) | 171 | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) | 615 | |

| Statistics | χ24 = 51.0; P < .001 | χ24 = 88.6; P < .001 | |||

| Education | χ23 = 21.6; P < .001 | ||||

| <High schoold | 1.9 (1.8-2.0) | 358 | 1.4 (1.3-1.5) | 929 | |

| High school | 1 [Reference] | 180 | 1 [Reference] | 633 | |

| Some college | 0.7 (0.5-0.9) | 121 | 0.9 (0.7-1.0) | 553 | |

| ≥College degree | 0.8 (0.6-1.0) | 123 | 0.8 (0.7-1.0) | 453 | |

| Statistics | χ23 = 307.4; P < .001 | χ23 = 130.0; P < .001 | |||

| Marital status | χ22 = 2.5; P = .28 | ||||

| Never married | 0.9 (0.9-1.0) | 206 | 1.0 (1.0-1.1) | 691 | |

| Currently married | 1 [Reference] | 222 | 1 [Reference] | 686 | |

| Previously married | 0.8 (0.5-1.1) | 164 | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | 676 | |

| Statistics | χ22 = 5.5; P = .06 | χ22 = 0.3; P = .85 | |||

| Service-Related Predictors | |||||

| Age at Army entry, y | χ22 = 12.2; P = .002 | ||||

| <21 | 1.2 (1.0-1.3) | 221 | 0.9 (0.9-1.0) | 664 | |

| 21-24 | 1 [Reference] | 189 | 1 [Reference] | 720 | |

| ≥25 | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) | 189 | 1.1 (1.0-1.2) | 793 | |

| Statistics | χ22 = 6.7; P = .03 | χ22 = 5.3; P = .07 | |||

| Time in service, y | χ24 = 10.5; P = .03 | ||||

| 1 | 6.0 (4.7-7.7) | 446 | 5.2 (4.5-6.0) | 2942 | |

| 2 | 2.9 (2.3-3.6) | 217 | 2.5 (2.2-2.8) | 1388 | |

| 3-4 | 1.9 (1.6-2.3) | 132 | 1.7 (1.5-1.8) | 736 | |

| 5-10 | 1 [Reference] | 66 | 1 [Reference] | 412 | |

| >10 | 0.4 (0.3-0.6) | 27 | 0.5 (0.4-0.6) | 195 | |

| Statistics | χ24 = 352.7; P < .001 | χ24 = 634.9; P < .001 | |||

| Deployment status | χ22 = 3.7; P = .16 | ||||

| Never deployed | 1.9 (1.7-2.2) | 224 | 2.2 (2.0-2.4) | 737 | |

| Currently deployed | 1 [Reference] | 114 | 1 [Reference] | 337 | |

| Previously deployed | 2.4 (2.1-2.8) | 256 | 2.6 (2.4-2.8) | 855 | |

| Statistics | χ22 = 143.4; P < .001 | χ22 = 458.3; P < .001 | |||

| Delayed promotion | χ23 = 22.3; P < .001 | ||||

| Late promotion ≤2 mo | 2.1 (1.7-2.6) | 442 | 1.7 (1.5-2.0) | 1386 | |

| Late promotion >2 mo | 1.7 (1.4-2.0) | 350 | 1.3 (1.2-1.4) | 1086 | |

| On schedule promotion | 1 [Reference] | 215 | 1 [Reference] | 836 | |

| Not relevant because of ranke | 0.8 (0.7-1.0) | 172 | 0.7 (0.6-0.7) | 540 | |

| Statistics | χ23 = 100.8; P < .001 | χ23 = 228.9; P < .001 | |||

| Demotion | χ22 = 8.6; P = .01 | ||||

| Demoted in past year | 1.6 (1.3-1.8) | 443 | 1.4 (1.3-1.5) | 1234 | |

| Demoted before past year | 1.3 (1.0-1.6) | 265 | 1.1 (1.0-1.3) | 757 | |

| Never demoted | 1 [Reference] | 203 | 1 [Reference] | 629 | |

| Statistics | χ22 = 25.9; P < .001 | χ22 = 45.0; P < .001 | |||

| Military occupation | χ23 = 18.1; P < .001 | ||||

| Combat arms | 1.2 (1.1-1.3) | 233 | 1.2 (1.1-1.3) | 779 | |

| Special forces | 0.4 (0.2-0.8) | 67 | 0.6 (0.3-1.1) | 369 | |

| Combat medic | 1.4 (1.2-1.6) | 276 | 1.3 (1.2-1.5) | 848 | |

| Other | 1 [Reference] | 199 | 1 [Reference] | 648 | |

| Statistics | χ23 = 39.0; P < .001 | χ23 = 67.7; P < .001 | |||

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; SRE, standardized risk estimate.

The sample of Regular Army enlisted soldiers (9650 cases [153 528 control person-months]) is a subset of the total Regular Army sample (193 617 person-months) from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) Historical Administrative Data Study. Control person-months were assigned a weight of 200 to adjust for undersampling.

Each 2-way interaction was examined separately in a model that included all of the sociodemographic and service-related variables but not the other 2-way interactions.

The SREs (number of soldiers with a suicide attempt per 100 000 person-years) were calculated assuming that other predictors were at their samplewide means.

Includes General Education Development credential, home study diploma, occupational program certificate, correspondence school diploma, high school certificate of attendance, adult education diploma, and other nontraditional high school credentials.

Soldiers above the rank of E4 are not promoted on a set schedule.

Marriage recency was associated with suicide attempt in both groups. Soldiers in the first month after marriage had lower odds of suicide attempt than those not currently married (OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4-0.9 for no MH-Dx and OR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.3-0.6 for any MH-Dx), and those 4 to 12 months after marriage had higher odds (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.0-1.3 for no MH-Dx and OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1-1.3 for any MH-Dx). Odds were higher 2 to 3 months after marriage only among soldiers with no previous MH-Dx (OR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.1-1.6). The association of marriage recency with suicide attempt differed by MH-Dx status because the OR for 2 to 3 months was larger among soldiers without previous MH-Dx (χ21 = 8.9; P = .003). Recency of marriage ending was not associated with suicide attempt in either MH-Dx group (Table 2).

Table 2. Multivariable Associations of Marriage Start/End Recency With Suicide Attempt Among Regular Army Enlisted Soldiers With and Without a History of Mental Health Diagnosisa.

| Variableb | No Previous Mental Health Diagnosis (n = 103 525) | Any Previous Mental Health Diagnosis (n = 59 653) | Predictor by Mental Health Historyc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | SREd | OR (95% CI) | SREd | ||

| I. Marriage start recency, mo | χ24 = 11.9; P = .02 | ||||

| 1 | 0.6 (0.4-0.9) | 124 | 0.4 (0.3-0.6) | 282 | |

| 2-3 | 1.3 (1.1-1.6) | 278 | 0.9 (0.7-1.0) | 594 | |

| 4-12 | 1.2 (1.0-1.3) | 244 | 1.2 (1.1-1.3) | 836 | |

| >12 | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | 211 | 1.0 (0.9-1.0) | 666 | |

| Not currently marriede | 1 [Reference] | 206 | 1 [Reference] | 689 | |

| Statistics | χ24 = 20.4; P < .001 | χ24 = 42.0; P < .001 | |||

| II. Marriage end recency, mo | χ25 = 3.4; P = .64 | ||||

| 1 | 1.0 (0.2-4.0) | 195 | 0.9 (0.5-1.7) | 592 | |

| 2-3 | 0.5 (0.1-1.8) | 98 | 1.0 (0.7-1.6) | 700 | |

| 4-12 | 0.9 (0.4-1.6) | 182 | 1.0 (0.8-1.3) | 704 | |

| >12 | 0.9 (0.5-1.5) | 176 | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) | 673 | |

| Currently married | 1.1 (1.0-1.2) | 224 | 1.0 (0.9-1.0) | 691 | |

| Never married | 1 [Reference] | 206 | 1 [Reference] | 687 | |

| Statistics | χ25 = 6.1; P = .30 | χ25 = 0.6; P = .99 | |||

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; SRE, standardized risk estimate.

The sample of Regular Army enlisted soldiers (9650 cases [153 528 control person-months]) is a subset of the total Regular Army sample (193 617 person-months) from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) Historical Administrative Data Study. Control person-months were assigned a weight of 200 to adjust for undersampling.

Each predictor (I and II) was examined in a separate logistic regression model that adjusted for sociodemographics (sex, current age, race/ethnicity, and education) and service-related variables, including age at Army entry, time in service (1, 2, 3-4, 5-10, or >10 years), deployment status (never, currently, or previously deployed), delayed promotion, demotion, and military occupation (combat arms, special forces, combat medic, or other). Models also included a dummy predictor variable for calendar month and year to control for secular trends. The marital status variable used in other models was removed for these analyses.

Each 2-way interaction was examined separately in a model that included all of the sociodemographic and service-related variables but not the other 2-way interactions.

The SREs (number of soldiers with a suicide attempt per 100 000 person-years) were calculated assuming that other predictors were at their samplewide means.

Includes soldiers who were never married or previously married.

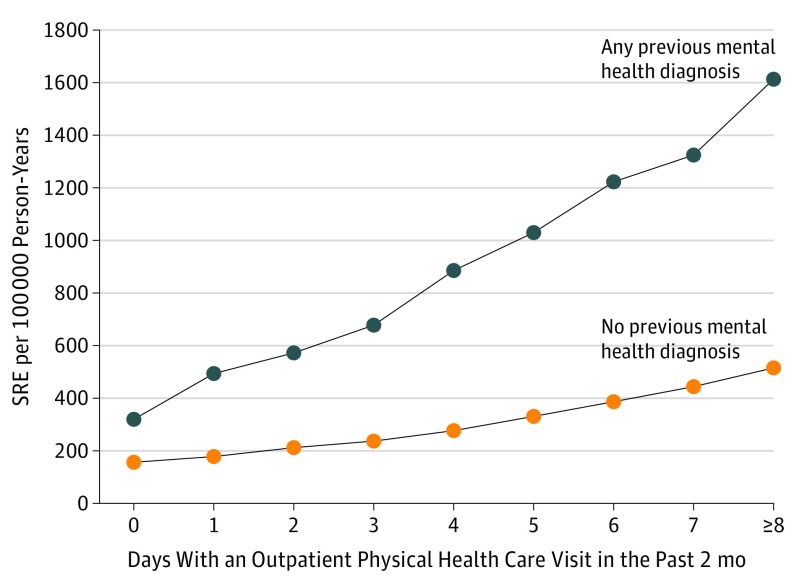

We examined physical health care visits in a series of separate adjusted models (Table 3 and Table 4). Among soldiers who attempted suicide, more than 72% of those without MH-Dx history and almost 87% of those with MH-Dx history had at least 1 OP-physical visit in the 2 months before their attempt. In both groups, odds of suicide attempt increased monotonically as visits increased. Among those with no previous MH-Dx, odds of attempt increased from 1 visit (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.0-1.3) to 8 or more visits (OR, 3.3; 95% CI, 2.9-3.8). Among those with a previous MH-Dx, odds of attempt increased from 1 visit (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.4-1.7) to 8 or more visits (OR, 5.1; 95% CI, 4.6-5.6). The association of OP-physical visits with suicide attempt differed by MH-Dx status (Table 3) because all ORs were significantly larger among soldiers with MH-Dx history (χ21 = 8.4-16.6; P ≤ .004 for all). The Figure shows the increase in standardized risk associated with OP-physical visits.

Table 3. Multivariable Associations of Outpatient Physical and Injury-Related Health Care Visits With Suicide Attempt Among Regular Army Enlisted Soldiers With and Without a History of Mental Health Diagnosisa.

| Variableb | No Previous Mental Health Diagnosis (n = 103 525) | Any Previous Mental Health Diagnosis (n = 59 653) | Predictor by Mental Health Historyc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | SREd | OR (95% CI) | SREd | ||

| I. Days with an outpatient physical health care visit in the past 2 mo | χ24 = 21.1; P < .001 | ||||

| 0 | 1 [Reference] | 155 | 1 [Reference] | 320 | |

| 1 | 1.2 (1.0-1.3) | 177 | 1.5 (1.4-1.7) | 494 | |

| 2-4 | 1.5 (1.4-1.6) | 231 | 2.1 (1.9-2.3) | 673 | |

| 5-7 | 2.4 (2.1-2.7) | 369 | 3.6 (3.3-4.0) | 1156 | |

| ≥8 | 3.3 (2.9-3.8) | 515 | 5.1 (4.6-5.6) | 1602 | |

| Statistics | χ24 = 427.9; P < .001 | χ24 = 1555.5; P < .001 | |||

| II. Previous injury-related health care visite | χ22 = 38.9; P < .001 | ||||

| Any inpatient visit for previous injury | 2.7 (2.1-3.4) | 409 | 3.1 (2.8-3.4) | 1562 | |

| Only outpatient visit for previous injury | 1.7 (1.6-1.8) | 269 | 1.4 (1.3-1.5) | 692 | |

| No visit for previous injury | 1 [Reference] | 153 | 1 [Reference] | 466 | |

| Statistics | χ22 = 232.3; P < .001 | χ22 = 527.8; P < .001 | |||

| III. Recency of last injury-related outpatient health care visit, moe | χ24 = 2.1; P = .71 | ||||

| 1 | 3.0 (2.8-3.3) | 426 | 3.0 (2.8-3.3) | 1182 | |

| 2 | 2.4 (2.1-2.7) | 337 | 2.6 (2.4-2.9) | 966 | |

| 3 | 2.2 (1.9-2.6) | 313 | 2.3 (2.0-2.6) | 864 | |

| ≥4 | 1.6 (1.5-1.8) | 233 | 1.7 (1.5-1.8) | 619 | |

| No outpatient visit for injury | 1 [Reference] | 139 | 1 [Reference] | 337 | |

| Statistics | χ24 = 658.1; P < .001 | χ24 = 836.8; P < .001 | |||

| IV. Recency of last injury-related inpatient health care visit, moe | χ24 = 11.3; P = .02 | ||||

| 1 | 3.8 (2.3-6.3) | 669 | 6.7 (5.7-7.8) | 3992 | |

| 2 | 2.4 (1.2-5.1) | 485 | 4.1 (3.2-5.1) | 2574 | |

| 3 | 1.6 (0.7-3.5) | 333 | 4.0 (3.1-5.0) | 2559 | |

| ≥4 | 1.6 (1.2-2.1) | 340 | 1.7 (1.5-1.8) | 1102 | |

| No inpatient visit for injury | 1 [Reference] | 208 | 1 [Reference] | 640 | |

| Statistics | χ24 = 41.5; P < .001 | χ24 = 899.0; P < .001 | |||

| V. Any previous combat injury | χ21 = 3.5; P = .06 | ||||

| Yes | 1.6 (1.0-2.4) | 337 | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) | 647 | |

| No | 1 [Reference] | 210 | 1 [Reference] | 689 | |

| Statistics | χ21 = 4.0; P = .047 | χ21 = 0.1; P = .72 | |||

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; SRE, standardized risk estimate.

The sample of Regular Army enlisted soldiers (9650 cases [153 528 control person-months]) is a subset of the total Regular Army sample (193 617 person-months) from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) Historical Administrative Data Study. Control person-months were assigned a weight of 200 to adjust for undersampling.

Each predictor (I-V) was examined in a separate logistic regression model that adjusted for sociodemographics (sex, current age, race/ethnicity, education, and marital status) and service-related variables, including age at Army entry, time in service (1, 2, 3-4, 5-10, or >10 years), deployment status (never, currently, or previously deployed), delayed promotion, demotion, and military occupation (combat arms, special forces, combat medic, or other). Models also included a dummy predictor variable for calendar month and year to control for secular trends.

Each 2-way interaction was examined separately in a model that included all of the sociodemographic and service-related variables but not the other 2-way interactions.

The SREs (number of soldiers with a suicide attempt per 100 000 person-years) were calculated assuming that other predictors were at their samplewide means.

These previous injuries were not suicide related according to information available in the administrative records.

Table 4. Multivariable Associations of Subjection to Crime, Crime Perpetration, and Family Violence With Suicide Attempt Among Regular Army Enlisted Soldiers With and Without a History of Mental Health Diagnosisa.

| Variableb | No Previous Mental Health Diagnosis (n = 103 525) | Any Previous Mental Health Diagnosis (n = 59 653) | Predictor by Mental Health Historyc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | SREd | OR (95% CI) | SREd | ||

| I. Subjection to crimee | χ23 = 2.2; P = .53 | ||||

| Major violent crime | 1.5 (1.0-2.2) | 307 | 1.7 (1.5-2.0) | 1175 | |

| Minor violent crime | 1.6 (1.1-2.4) | 342 | 1.3 (1.1-1.5) | 866 | |

| Nonviolent crime | 1.2 (0.9-1.4) | 240 | 1.1 (1.0-1.2) | 737 | |

| Not subjected to crime | 1 [Reference] | 208 | 1 [Reference] | 670 | |

| Statistics | χ23 = 12.1; P = .007 | χ23 = 71.8; P < .001 | |||

| II. Crime perpetratione | χ23 = 34.1; P < .001 | ||||

| Major violent crime | 2.0 (1.3-3.0) | 397 | 1.9 (1.7-2.2) | 1186 | |

| Minor violent crime | 1.8 (1.3-2.5) | 350 | 1.6 (1.4-1.8) | 1003 | |

| Nonviolent crime | 2.0 (1.8-2.3) | 396 | 1.4 (1.4-1.5) | 886 | |

| No crime perpetration | 1 [Reference] | 198 | 1 [Reference] | 608 | |

| Statistics | χ23 = 149.7; P < .001 | χ23 = 224.8; P < .001 | |||

| III. Family violencef | χ21 = 12.9; P < .001 | ||||

| Yes | 2.9 (1.9-4.4) | 607 | 1.5 (1.4-1.7) | 1052 | |

| No | 1 [Reference] | 210 | 1 [Reference] | 666 | |

| Statistics | χ21 = 24.1; P < .001 | χ21 = 85.4; P < .001 | |||

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; SRE, standardized risk estimate.

The sample of Regular Army enlisted soldiers (9650 cases [153 528 control person-months]) is a subset of the total Regular Army sample (193 617 person-months) from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) Historical Administrative Data Study. Control person-months were assigned a weight of 200 to adjust for undersampling.

Each predictor (I-III) was examined in a separate logistic regression model that adjusted for sociodemographics (sex, current age, race/ethnicity, education, and marital status) and service-related variables, including age at Army entry, time in service (1, 2, 3-4, 5-10, or >10 years), deployment status (never, currently, or previously deployed), delayed promotion, demotion, and military occupation (combat arms, special forces, combat medic, or other). Models also included a dummy predictor variable for calendar month and year to control for secular trends.

Each 2-way interaction was examined separately in a model that included all of the sociodemographic and service-related variables but not the other 2-way interactions.

The SREs (number of soldiers with a suicide attempt per 100 000 person-years) were calculated assuming that other predictors were at their samplewide means.

Includes only founded crimes. Categories are hierarchical and mutually exclusive such that soldiers were classified based on the most serious crime in their records (major violent crime > minor violent crime > nonviolent crime).

Includes any history of being subjected to or perpetrating family violence based on legal, Army Central Registry, or medical records.

Figure. Standardized Risk of Suicide Attempt by Number of Days With an Outpatient Physical Health Care Visit in the Past 2 Months Among Regular Army Enlisted Soldiers With and Without a History of Mental Health Diagnosis.

The sample of Regular Army enlisted soldiers (9650 cases [153 528 control person-months]) is a subset of the total Regular Army sample (193 617 person-months) from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) Historical Administrative Data Study. Control person-months were assigned a weight of 200 to adjust for undersampling. The standardized risk estimate (SRE) (number of soldiers with a suicide attempt per 100 000 person-years) was calculated assuming that other predictors were at their samplewide means. The SREs were calculated using a logistic regression analysis that adjusted for sociodemographics (sex, current age, race/ethnicity, education, and marital status) and service-related variables, including age at Army entry, time in service (1, 2, 3-4, 5-10, or >10 years), deployment status (never, currently, or previously deployed), delayed promotion, demotion, and military occupation (combat arms, special forces, combat medic, or other). The model also included a dummy predictor variable for calendar month and year to control for secular trends.

Among those with no previous MH-Dx, elevated odds of suicide attempt were associated with previous IP-injury (OR, 2.7; 95% CI, 2.1-3.4) and OP-injury (OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.6-1.8). Soldiers with a previous MH-Dx also had higher odds if they ever had an IP-injury (OR, 3.1; 95% CI, 2.8-3.4) or OP-injury (OR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.3-1.5). The association of injury-related health care visits with suicide attempt differed by MH-Dx status (Table 3) because the OR for OP-injury visit was larger among soldiers with an MH-Dx history (χ21 = 29.9; P < .001).

Odds of suicide attempt increased with recency of OP-injury and IP-injury in both MH-Dx groups. Among soldiers with no MH-Dx history, odds of attempt were highest for past-month OP-injury visit (OR, 3.0; 95% CI, 2.8-3.3) and lowest for a visit at least 4 months prior (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.5-1.8). This pattern was the same for soldiers with previous MH-Dx. Odds of attempt were similarly highest for past-month IP-injury among those without (OR, 3.8; 95% CI, 2.3-6.3) and with (OR, 6.7; 95% CI, 5.7-7.8) MH-Dx history. The association of IP-injury recency with suicide attempt differed by MH-Dx status (Table 3) because the ORs for 1 month (χ21 = 4.0; P = .047) and 3 months (χ21 = 5.3; P = .02) were larger among soldiers with previous MH-Dx. Combat injury was associated with increased odds of suicide attempt only among those with no MH-Dx history (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.0-2.4).

Subjection to crime, crime perpetration, and family violence were associated with suicide attempt in both MH-Dx groups. Relative to those who were not subjected to crime, soldiers without previous MH-Dx had higher odds of suicide attempt if they were subjected to a minor violent crime (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.1-2.4) but not other crimes. Soldiers with previous MH-Dx who were subjected to any category of crime had elevated odds of attempt ranging from major violent crime (OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.5-2.0) to nonviolent crime (OR, 1.1; 95% CI, 1.0-1.2). In both groups, perpetration in any crime category was associated with higher odds of suicide attempt, particularly major violent crime (OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3-3.0 for no MH-Dx and OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.7-2.2 for any MH-Dx). Family violence history was also associated with increased odds of suicide attempt in both groups (OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.9-4.4 for no MH-Dx and OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.4-1.7 for any MH-Dx). Associations of crime perpetration and family violence with suicide attempt differed by MH-Dx history, but being subjected to crime did not (Table 4). The ORs for nonviolent crime perpetration (χ21 = 33.9; P < .001) and family violence (χ21 = 12.9; P < .001) were higher among soldiers with no MH-Dx history. Additional descriptive data and nonstratified results are listed in eTables 8 through 14 in the Supplement.

Discussion

More than one-third of enlisted soldiers who attempted suicide had no MH-Dx history. It is likely that many of these soldiers had undetected mental disorders.5,43,44 Mental health problems may go undiagnosed because a soldier (1) did not perceive a need for treatment or did not seek help45; (2) was not assessed for mental health problems during medical evaluations; (3) did not report symptoms during postdeployment screening46; (4) screened positive but did not follow up on the referral47; or (5) screened positive and followed up, but the evaluation did not result in MH-Dx. Ensuring adequate functioning of programs to facilitate detection and treatment is essential and may be aided by improving mental health knowledge among soldiers48 and maximizing a culture of honest symptom reporting.49 Detection may be enhanced through expanded mental health screening in primary care, a universal access point to Army health care. Screening before basic training would benefit new soldiers because many enter the Army with a history of mental disorders and suicide ideation.50,51 In the present study, almost 60% of undiagnosed soldiers who attempted suicide were in their first year of service (vs about 21% of those with previous MH-Dx), suggesting that there was less time for problems to be detected and treated. This factor is noteworthy because, as in the general population,4 most transitions from ideation to attempt among soldiers occur within 1 year of ideation onset.11,50,52

It is possible that some of those with no previous MH-Dx who attempted suicide did not have a mental disorder. For those soldiers, it might be expected that acute stressors have a significant role in their suicide attempt. Some results support this idea: for example, delayed promotion, demotion, and family violence had stronger associations with suicide attempt among those without previous MH-Dx. However, this interpretation is complicated by the fact that previous injuries, particularly recent injuries, had a stronger association with suicide attempt among those with MH-Dx history. This may support a vulnerability-stress model of suicidal behavior,53 in which suicide attempt results from the interaction of stressors (eg, injuries) with the preexisting vulnerability/diathesis (eg, MH-Dx).

Sociodemographic and service-related predictors of suicide attempt were similar among soldiers in both MH-Dx groups, although ORs were generally larger in those with no MH-Dx history. In particular, being female increased odds of suicide attempt in both groups, but more so among soldiers without previous MH-Dx. Women with no MH-Dx history may be more likely to have undetected mental health problems or unreported exposure to violence or discrimination. Given the large proportion of first-year soldiers in the group without previous MH-Dx, it is possible that women face additional stressors and challenges in the initial months of service. Perhaps surprisingly, all soldiers had decreased suicide attempt risk in the first month after marriage and increased risk 4 to 12 months after marriage, highlighting how risk may change during transitions. The lack of findings associated with end of marriage may reflect the discrepancy between when the breakup began vs when it was administratively recorded.

Regardless of MH-Dx status, soldiers who attempted suicide were higher users of OP-physical health care than controls and more likely to have sustained an injury. More than 72% of suicide attempt cases with no previous MH-Dx had at least 1 OP-physical visit in the past 2 months. However, risk detection remains a challenge because soldiers in general access medical care at a high rate. Consistent with previous findings,24 suicide attempt risk was higher in both MH-Dx groups shortly after treatment for injuries, particularly inpatient-related injuries. Injuries can result in significant mental health morbidity, increasing risk of suicide attempts over time.54,55 Future research should examine whether injury type, repeated injuries, and other physical health problems56,57,58 are predictive of suicide attempts.

Increased suicide attempt risk associated with being subjected to crime, crime perpetration, and family violence is consistent with previous studies.25,26,27,28,30,31,32,33,34,59 Risk was particularly elevated among perpetrators in both MH-Dx groups and among soldiers with no previous MH-Dx who had documented family violence. These community access points offer opportunities for suicide risk assessment. Future research should examine number and recency of specific crimes, as well as interactions with sociodemographic and service-related characteristics (eg, sex and deployment history).26,27,29,31

Limitations

This study has noteworthy limitations. First, administrative records are limited to events that come to the Army’s attention and are subject to classification and coding errors. Unreported suicide attempts, mental disorders, and crimes/family violence (eg, sexual assault and spousal abuse) were not captured. Future analyses of Army STARRS survey data that are linked to respondents’ administrative records will allow for examination of undiagnosed mental disorders, subthreshold mental disorders, and undocumented stressful events among soldiers with no MH-Dx. Second, our injury variable may have captured injuries that were self-inflicted but unrecognized as such. Third, although the interaction tests adjusted for the main associations of other covariates, they did not adjust for other potential interactions. Fourth, our findings may not generalize to other periods or populations.

Conclusions

Interactions with medical, legal, and family services systems create assessment and prevention opportunities for soldiers with previously undetected suicide attempt risk. Machine learning models incorporating variables from disparate Army data systems can provide decision support tools to assist community service providers and clinicians in targeting interventions and deploying resources.59,60 Army STARRS has produced such algorithms to detect concentration of risk for suicide and other adverse outcomes within the health care61,62 and legal63,64,65 systems. The accuracy of these models can be further improved through the addition of self-report screening data.66 Findings also highlight the importance of strengthening mental health care embedded within primary care. Although one-third of soldiers who attempted suicide had no previous MH-Dx, most had an OP-physical visit in the weeks before their attempt. The Army has implemented mental screening and collaborative care programs in primary care settings to improve recognition and clinical management of mental disorders.67,68 Ensuring routine assessment of psychological distress and suicide risk during all encounters can help identify at-risk soldiers who are unknown to the mental health care system.

eTable 1. List and Brief Descriptions of Administrative Data Systems Included in the 2004-2009 Army STARRS Historical Administrative Data Study (HADS)

eTable 2. List of Military Occupational Specialties (MOS) in the 2004-2009 Army STARRS Historical Administrative Data Study (HADS) That Were Categorized as Combat Arms, Special Forces, and Combat Medic

eTable 3. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision–Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) Codes Used to Identify Mental Disorders

eTable 4. The National Corrections Reporting Program (NCRP) Offense Codes Used to Identify Categories of Criminal Perpetration and Victimization

eTable 5. List of Family Violence-Related Data Sources Included in the 2004-2009 Army STARRS Historical Administrative Data Study (HADS)

eTable 6. The National Corrections Reporting Program (NCRP) Offense Codes Used to Identify Family Violence

eTable 7. Multivariable Associations of Sociodemographic, Service-Related, and Mental Health Variables With Suicide Attempt in the Total Sample of Regular Army Enlisted Soldiers

eTable 8. Counts and Rates of Suicide Attempts by Sociodemographic and Service-Related Variables Among Regular Army Enlisted Soldiers With and Without a History of Mental Health Diagnosis

eTable 9. Multivariable Associations of Marriage Start/End Recency With Suicide Attempt in the Total Sample of Regular Army Enlisted Soldiers

eTable 10. Counts and Rates of Suicide Attempts by Marriage Start/End Recency Among Regular Army Enlisted Soldiers With and Without a History of Mental Health Diagnosis

eTable 11. Counts and Rates of Suicide Attempts by Marriage Start/End Recency Among Regular Army Enlisted Soldiers With and Without a History of Mental Health Diagnosis

eTable 12. Counts and Rates of Suicide Attempts by Outpatient Physical and Injury-Related Healthcare Visits Among Regular Army Enlisted Soldiers With and Without a History of Mental Health Diagnosis

eTable 13. Multivariable Associations of Crime Victimization/Perpetration and Family Violence With Suicide Attempt in the Total Sample of Regular Army Enlisted Soldiers

eTable 14. Counts and Rates of Suicide Attempts by Crime Victimization/Perpetration and Family Violence Among Regular Army Enlisted Soldiers With and Without a History of Mental Health Diagnosis

References

- 1.Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, Heeringa SG, et al. ; Army STARRS Collaborators . Nonfatal suicidal behaviors in U.S. Army administrative records, 2004-2009: results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Psychiatry. 2015;78(1):1-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoenbaum M, Kessler RC, Gilman SE, et al. ; Army STARRS Collaborators . Predictors of suicide and accident death in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS): results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):493-503. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black SA, Gallaway MS, Bell MR, Ritchie EC. Prevalence and risk factors associated with suicides of Army soldiers 2001-2009. Mil Psychol. 2011;23(4):433-451. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(7):617-626. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavanagh JT, Carson AJ, Sharpe M, Lawrie SM. Psychological autopsy studies of suicide: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2003;33(3):395-405. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702006943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Borges G, Nock M, Wang PS. Trends in suicide ideation, plans, gestures, and attempts in the United States, 1990-1992 to 2001-2003. JAMA. 2005;293(20):2487-2495. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petronis KR, Samuels JF, Moscicki EK, Anthony JC. An epidemiologic investigation of potential risk factors for suicide attempts. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1990;25(4):193-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris EC, Barraclough B. Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders: a meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:205-228. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.3.205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, Stein MB, et al. ; Army STARRS Collaborators . Risk factors, methods, and timing of suicide attempts among U.S. Army soldiers. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(7):741-749. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, Stein MB, et al. ; Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers Collaborators . Suicide attempts in the U.S. Army during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, 2004-2009. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(9):917-926. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nock MK, Stein MB, Heeringa SG, et al. ; Army STARRS Collaborators . Prevalence and correlates of suicidal behavior among soldiers: results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):514-522. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Millner AJ, Ursano RJ, Hwang I, et al. STARRS-LS Collaborators. Prior mental disorders and lifetime suicidal behaviors among US Army soldiers in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) [published online September 19, 2017]. Suicide Life Threat Behav. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skopp NA, Zhang Y, Smolenski DJ, Reger MA. Risk factors for self-directed violence in US soldiers: a case-control study. Psychiatry Res. 2016;245:194-199. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bachynski KE, Canham-Chervak M, Black SA, Dada EO, Millikan AM, Jones BH. Mental health risk factors for suicides in the US Army, 2007-8. Inj Prev. 2012;18(6):405-412. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2011-040112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Britton PC, Ilgen MA, Valenstein M, Knox K, Claassen CA, Conner KR. Differences between veteran suicides with and without psychiatric symptoms. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(suppl 1):S125-S130. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, Naifeh JA, et al. ; Army STARRS Collaborators . Suicide attempts in U.S. Army combat arms, special forces and combat medics. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):194. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1350-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stack S, Scourfield J. Recency of divorce, depression, and suicide risk. J Fam Issues. 2015;36(6):695-715. doi: 10.1177/0192513X13494824 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Batterham PJ, Fairweather-Schmidt AK, Butterworth P, Calear AL, Mackinnon AJ, Christensen H. Temporal effects of separation on suicidal thoughts and behaviours. Soc Sci Med. 2014;111:58-63. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen YC, Cunha JM, Williams TV. Time-varying associations of suicide with deployments, mental health conditions, and stressful life events among current and former US military personnel: a retrospective multivariate analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(11):1039-1048. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30304-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luoma JB, Martin CE, Pearson JL. Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: a review of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(6):909-916. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trofimovich L, Skopp NA, Luxton DD, Reger MA. Health care experiences prior to suicide and self-inflicted injury, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2001-2010. MSMR. 2012;19(2):2-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ribeiro JD, Gutierrez PM, Joiner TE, et al. Health care contact and suicide risk documentation prior to suicide death: results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). J Consult Clin Psychol. 2017;85(4):403-408. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryb GE, Soderstrom CA, Kufera JA, Dischinger P. Longitudinal study of suicide after traumatic injury. J Trauma. 2006;61(4):799-804. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000196763.14289.4e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bell NS, Harford TC, Amoroso PJ, Hollander IE, Kay AB. Prior health care utilization patterns and suicide among U.S. Army soldiers. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2010;40(4):407-415. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.4.407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LeBouthillier DM, McMillan KA, Thibodeau MA, Asmundson GJ. Types and number of traumas associated with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in PTSD: findings from a U.S. nationally representative sample. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(3):183-190. doi: 10.1002/jts.22010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Webb RT, Shaw J, Stevens H, Mortensen PB, Appleby L, Qin P. Suicide risk among violent and sexual criminal offenders. J Interpers Violence. 2012;27(17):3405-3424. doi: 10.1177/0886260512445387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Webb RT, Qin P, Stevens H, Mortensen PB, Appleby L, Shaw J. National study of suicide in all people with a criminal justice history. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(6):591-599. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stein DJ, Chiu WT, Hwang I, et al. Cross-national analysis of the associations between traumatic events and suicidal behavior: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10574. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooper J, Appleby L, Amos T. Life events preceding suicide by young people. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37(6):271-275. doi: 10.1007/s001270200019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Devries KM, Mak JY, Bacchus LJ, et al. Intimate partner violence and incident depressive symptoms and suicide attempts: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5):e1001439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ursano RJ, Stein MB, Herberman Mash HB, et al. Documented family violence and risk of suicide attempt among U.S. Army soldiers. Psychiatry Res. 2018;262:575-582. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.09.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Snarr JD, Slep AM, Heyman RE, Foran HM; United States Air Force Family Advocacy Program . Risk for suicidal ideation in the U.S. Air Force: an ecological perspective. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(5):600-612. doi: 10.1037/a0024631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cerulli C, Stephens B, Bossarte R. Examining the intersection between suicidal behaviors and intimate partner violence among a sample of males receiving services from the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Mens Health. 2014;8(5):440-443. doi: 10.1177/1557988314522828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Belik SL, Stein MB, Asmundson GJ, Sareen J. Relation between traumatic events and suicide attempts in Canadian military personnel. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(2):93-104. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ursano RJ, Colpe LJ, Heeringa SG, Kessler RC, Schoenbaum M, Stein MB; Army STARRS Collaborators . The Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Psychiatry. 2014;77(2):107-119. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2014.77.2.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kessler RC, Colpe LJ, Fullerton CS, et al. Design of the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2013;22(4):267-275. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Willett JB, Singer JD. Investigating onset, cessation, relapse, and recovery: why you should, and how you can, use discrete-time survival analysis to examine event occurrence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61(6):952-965. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.61.6.952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gahm GA, Reger MA, Kinn JT, Luxton DD, Skopp NA, Bush NE. Addressing the surveillance goal in the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: the Department of Defense Suicide Event Report. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(suppl 1):S24-S28. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hauret KG, Jones BH, Bullock SH, Canham-Chervak M, Canada S. Musculoskeletal injuries: description of an under-recognized injury problem among military personnel. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(1)(suppl):S61-S70. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amoroso PJ, Bell NS, Smith GS, Senier L, Pickett D. Viewpoint: a comparison of cause-of-injury coding in U.S. military and civilian hospitals. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(3)(suppl):164-173. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00176-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.SAS 9.4 Software [computer program]. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roalfe AK, Holder RL, Wilson S. Standardisation of rates using logistic regression: a comparison with the direct method. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:275. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Kessler RC. Mental disorders, comorbidity and suicidal behavior: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(8):868-876. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nock MK, Dempsey CL, Aliaga PA, et al. Psychological autopsy study comparing suicide decedents, suicide ideators, and propensity score matched controls: results from the Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Psychol Med. 2017;47(15):2663-2674. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717001179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Naifeh JA, Colpe LJ, Aliaga PA, et al. ; Army STARRS Collaborators . Barriers to initiating and continuing mental health treatment among soldiers in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Mil Med. 2016;181(9):1021-1032. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bliese PD, Wright KM, Adler AB, Thomas JL, Hoge CW. Timing of postcombat mental health assessments. Psychol Serv. 2007;4(3):141-148. doi: 10.1037/1541-1559.4.3.141 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoge CW, Grossman SH, Auchterlonie JL, Riviere LA, Milliken CS, Wilk JE. PTSD treatment for soldiers after combat deployment: low utilization of mental health care and reasons for dropout. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(8):997-1004. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomas JL, Adrian AL, Penix EA, Wilk JE, Adler AB. Mental health literacy in U.S. soldiers: knowledge of services and processes in the utilization of military mental health care. Mil Behav Health. 2016;4(2):92-99. doi: 10.1080/21635781.2016.1153541 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Warner CH, Appenzeller GN, Grieger T, et al. Importance of anonymity to encourage honest reporting in mental health screening after combat deployment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(10):1065-1071. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ursano RJ, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, et al. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal behavior among new soldiers in the U.S. Army: results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(1):3-12. doi: 10.1002/da.22317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosellini AJ, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, et al. Lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV mental disorders among new soldiers in the U.S. Army: results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(1):13-24. doi: 10.1002/da.22316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Millner AJ, Ursano RJ, Hwang I, et al. ; STARRS-LS Collaborators . Lifetime suicidal behaviors and career characteristics among U.S. Army soldiers: results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2018;48(2):230-250. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ingram RE, Luxton DD. Vulnerability-stress models In: Hankin BL, Abela JRZ, eds. Development of Psychopathology: A Vulnerability-Stress Perspective. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2005:32-46. doi: 10.4135/9781452231655.n2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grieger TA, Cozza SJ, Ursano RJ, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in battle-injured soldiers. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(10):1777-1783. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.10.1777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O’Donnell ML, Creamer M, Bryant RA, Schnyder U, Shalev A. Posttraumatic disorders following injury: an empirical and methodological review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2003;23(4):587-603. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(03)00036-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lund-Sørensen H, Benros ME, Madsen T, et al. A nationwide cohort study of the association between hospitalization with infection and risk of death by suicide. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(9):912-919. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Webb RT, Kontopantelis E, Doran T, Qin P, Creed F, Kapur N. Suicide risk in primary care patients with major physical diseases: a case-control study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(3):256-264. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ilgen MA, Kleinberg F, Ignacio RV, et al. Noncancer pain conditions and risk of suicide. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(7):692-697. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Elonheimo H, Sillanmäki L, Sourander A. Crime and mortality in a population-based nationwide 1981 birth cohort: results from the FinnCrime study. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2017;27(1):15-26. doi: 10.1002/cbm.1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kessler RC. The potential of predictive analytics to provide clinical decision support in depression treatment planning. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2018;31(1):32-39. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kessler RC, Warner CH, Ivany C, et al. ; Army STARRS Collaborators . Predicting suicides after psychiatric hospitalization in US Army soldiers: the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(1):49-57. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kessler RC, Stein MB, Petukhova MV, et al. ; Army STARRS Collaborators . Predicting suicides after outpatient mental health visits in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22(4):544-551. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rosellini AJ, Monahan J, Street AE, et al. Predicting sexual assault perpetration in the U.S. Army using administrative data. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(5):661-669. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.06.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rosellini AJ, Monahan J, Street AE, et al. Using administrative data to identify U.S. Army soldiers at high-risk of perpetrating minor violent crimes. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;84:128-136. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.09.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rosellini AJ, Monahan J, Street AE, et al. Predicting non-familial major physical violent crime perpetration in the US Army from administrative data. Psychol Med. 2016;46(2):303-316. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bernecker SL, Rosellini AJ, Nock MK, et al. Improving risk prediction accuracy for new soldiers in the U.S. Army by adding self-report survey data to administrative data. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):87. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1656-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wong EC, Jaycox LH, Ayer L, et al. Evaluating the Implementation of the Re-Engineering Systems of Primary Care Treatment in the Military (RESPECT-Mil). Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corp; 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Engel CC, Oxman T, Yamamoto C, et al. RESPECT-Mil: feasibility of a systems-level collaborative care approach to depression and post-traumatic stress disorder in military primary care. Mil Med. 2008;173(10):935-940. doi: 10.7205/MILMED.173.10.935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. List and Brief Descriptions of Administrative Data Systems Included in the 2004-2009 Army STARRS Historical Administrative Data Study (HADS)

eTable 2. List of Military Occupational Specialties (MOS) in the 2004-2009 Army STARRS Historical Administrative Data Study (HADS) That Were Categorized as Combat Arms, Special Forces, and Combat Medic

eTable 3. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision–Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) Codes Used to Identify Mental Disorders

eTable 4. The National Corrections Reporting Program (NCRP) Offense Codes Used to Identify Categories of Criminal Perpetration and Victimization

eTable 5. List of Family Violence-Related Data Sources Included in the 2004-2009 Army STARRS Historical Administrative Data Study (HADS)

eTable 6. The National Corrections Reporting Program (NCRP) Offense Codes Used to Identify Family Violence

eTable 7. Multivariable Associations of Sociodemographic, Service-Related, and Mental Health Variables With Suicide Attempt in the Total Sample of Regular Army Enlisted Soldiers

eTable 8. Counts and Rates of Suicide Attempts by Sociodemographic and Service-Related Variables Among Regular Army Enlisted Soldiers With and Without a History of Mental Health Diagnosis

eTable 9. Multivariable Associations of Marriage Start/End Recency With Suicide Attempt in the Total Sample of Regular Army Enlisted Soldiers

eTable 10. Counts and Rates of Suicide Attempts by Marriage Start/End Recency Among Regular Army Enlisted Soldiers With and Without a History of Mental Health Diagnosis

eTable 11. Counts and Rates of Suicide Attempts by Marriage Start/End Recency Among Regular Army Enlisted Soldiers With and Without a History of Mental Health Diagnosis

eTable 12. Counts and Rates of Suicide Attempts by Outpatient Physical and Injury-Related Healthcare Visits Among Regular Army Enlisted Soldiers With and Without a History of Mental Health Diagnosis

eTable 13. Multivariable Associations of Crime Victimization/Perpetration and Family Violence With Suicide Attempt in the Total Sample of Regular Army Enlisted Soldiers

eTable 14. Counts and Rates of Suicide Attempts by Crime Victimization/Perpetration and Family Violence Among Regular Army Enlisted Soldiers With and Without a History of Mental Health Diagnosis