Key Points

Question

Are functional variants in Bcl2-associated anthanogene (BAG) found in individuals of African ancestry with dilated cardiomyopathy, and are they associated with specific outcomes?

Findings

This cohort study demonstrates the presence of unique genetic variants in BAG3 found almost exclusively in African American individuals that are associated with a nearly 2-fold greater risk of having an adverse cardiovascular outcome. In addition, this study assesses the pathogenicity of genetic variants and their association with protein levels in the human heart.

Meaning

Per this analysis, mutations in BAG3 may play an important role in cardiovascular pathobiology in individuals of African ancestry.

This study combined secondary analysis of 5 cohorts with murine modeling to assess the association of Bcl2-associated anthanogene 3 (BAG3) genetic variants with outcomes in individuals of African ancestry with dilated cardiomyopathy.

Abstract

Importance

The prevalence of nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is greater in individuals of African ancestry than in individuals of European ancestry. However, little is known about whether the difference in prevalence or outcomes is associated with functional genetic variants.

Objective

We hypothesized that Bcl2-associated anthanogene 3 (BAG3) genetic variants were associated with outcomes in individuals of African ancestry with DCM.

Design

This multicohort study of the BAG3 genotype in patients of African ancestry with dilated cardiomyopathy uses DNA obtained from African American individuals enrolled in 3 clinical studies: the Genetic Risk Assessment of African Americans With Heart Failure (GRAHF) study; the Intervention in Myocarditis and Acute Cardiomyopathy Trial-2 (IMAC-2) study; and the Genetic Risk Assessment of Cardiac Events (GRACE) study. Samples of DNA were also acquired from the left ventricular myocardium of patients of African ancestry who underwent heart transplant at the University of Colorado and University of Pittsburgh.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary end points were the prevalence of BAG3 mutations in African American individuals and event-free survival in participants harboring functional BAG3 mutations.

Results

Four BAG3 genetic variants were identified; these were expressed in 42 of 402 African American individuals (10.4%) with nonischemic heart failure and 9 of 107 African American individuals (8.4%) with ischemic heart failure but were not present in a reference population of European ancestry (P < .001). The variants included 2 nonsynonymous single-nucleotide variants; 1 three-nucleotide in-frame insertion; and 2 single-nucleotide variants that were linked in cis. The presence of BAG3 variants was associated with a nearly 2-fold (hazard ratio, 1.97 [95% CI, 1.19-3.24]; P = .01) increase in cardiac events in carriers compared with noncarriers. Transfection of transformed adult human ventricular myocytes with plasmids expressing the 4 variants demonstrated that each variant caused an increase in apoptosis and a decrease in autophagy when samples were subjected to the stress of hypoxia-reoxygenation.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study demonstrates that genetic variants in BAG3 found almost exclusively in individuals of African ancestry were not causative of disease but were associated with a negative outcome in patients with a dilated cardiomyopathy through modulation of the function of BAG3. The results emphasize the importance of biological differences in causing phenotypic variance across diverse patient populations, the need to include diverse populations in genetic cohorts, and the importance of determining the pathogenicity of genetic variants.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) secondary to dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) affects an estimated 2.5 million Americans 20 years or older.1 The epidemiology of DCM differs by race and ethnicity, with American individuals of African ancestry having the highest incidence and prevalence of HF and a preponderance of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (IDC).2,3 This contrasts with American individuals of European ancestry, who most commonly have DCM secondary to ischemic heart disease.4,5,6,7 Consistent with the epidemiology of IDC in American individuals of African ancestry, IDC is far more common and the age at which the disease is first recognized is substantially lower in sub-Saharan Africa than in the United States or in Europe.8,9

The increased prevalence of DCM in US people of African ancestry has been attributed to a diverse set of medical and sociologic factors, including neighborhood,10 and a higher burden of cardiovascular risk factors, including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cholesterol, smoking status, and ventricular hypertrophy.11 Several observations, however, suggest that the increased incidence of IDC may also be attributed to genetic risk factors. For example, HF hot spots are found in geographic regions across sub-Saharan Africa.12 The presence of hypertension does not correlate strongly with DCM in sub-Saharan African individuals.13 Truncating variants in TTN, the gene most commonly associated with DCM,14 are more prevalent in women of African ancestry with postpartum cardiomyopathy than in women of European ancestry with postpartum cardiomyopathy.15

Genetic variants in more than 40 genes have been linked with DCM. One such gene encodes Bcl-2–associated athanogene 3 (BAG3), an evolutionarily conserved protein that is expressed predominantly in the heart and skeletal muscle and in many cancers.16 The BAG3 protein has pleotropic effects in the heart17,18 and has emerged as a major DCM locus.19 Several observations suggest that BAG3 mutations might be prevalent in African American individuals.20 The Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) shows marked differences between the allele frequency of BAG3 variants found commonly in individuals of African ancestry when compared with the allele frequency of BAG3 variants in individuals of European ancestry.21

To investigate whether BAG3 variants contribute to either the increased prevalence or the clinical outcomes of IDC in African American individuals, we sequenced BAG3 in DNA samples obtained from participants who were enrolled in 1 of 3 clinical trials.

Methods

The primary objective of this study was to determine via a retrospective analysis whether genetic variants in BAG3 found in individuals of African ancestry were associated with either the prevalence of the disease or disease outcome in patients with heart failure because of reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). The study began with an exploratory assessment of BAG3 variants in patients enrolled in the Genetic Risk Assessment of African Americans With Heart Failure (GRAHF) trial. Subsequent analysis in African American individuals who participated in 2 additional HFrEF trials provided a larger population with which to evaluate the study end points. A secondary objective of the study was to determine the pathogenicity of the variants that were identified.

Patients

Genomic DNA was obtained from 509 African American individuals with DCM enrolled in 3 independent US studies: 342 patients from the GRAHF trial22,23,24,25; 109 patients from the Intervention in Myocarditis and Acute Cardiomyopathy Trial-2 (IMAC-2) study26; and 58 patients from the Genetic Risk Assessment of Cardiac Events (GRACE) study.27,28 Patients were excluded from analysis if they had acute myocarditis, peripartum cardiomyopathy, or any potentially reversible cause for DCM.29 Patients in the GRAHF and IMAC-2 studies were followed up to an end point of death or HF hospitalization adjudicated by an end point committee. Participants in the GRACE study were followed up to the end point of heart transplant or death. Samples of DNA were also acquired from the left ventricular (LV) myocardium of participants of African ancestry who underwent heart transplantation at the University of Colorado (n = 15) or at the University of Pittsburgh (n = 31). Nonfailing human heart tissue that could not be used for transplant served as nonfailing control samples.30

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients (or appropriate family members) who contributed DNA or tissue to the aforementioned study repositories. The study protocols were approved by the institutional review board at each of the participating institutions.

We used 3 reference populations. First, we sequenced DNA from individuals of African ancestry with ischemic cardiomyopathy who were enrolled in the GRAHF, IMAC-2, and GRACE studies (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Second, we obtained BAG3 sequence data from a cohort of 359 individuals of European ancestry with both familial and sporadic DCM, collected at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, from clinics throughout the United States.31 Third, population genetic data from gnomAD were accessed online, including data from 123 136 exome sequences and 15 496 whole-genome sequences from unrelated individuals. Of these, 7509 whole genomes and 55 860 exomes are from individuals of non-Finnish European ancestry, and 4368 whole genomes and 7652 exome sequences are from individuals of African ancestry.21

DNA Sequencing and Analyses

The DNA samples from the GRAHF trial were sequenced in the Genetics Resources Core Facility at the McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, as described in detail in the eMethods in the Supplement. Targeted genotyping was performed to confirm the results of the GRAHF cohort and to identify single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) in each of the subsequent cohorts using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)–specific reagents (eMethods in the Supplement). The SNVs were chosen for confirmatory genotyping and functional analysis if they (1) had an allele frequency of more than 0.005 in the GRAHF study, (2) were nonsynonymous, and (3) were more common in participants of African ancestry than in those of European ancestry. To determine whether 2 BAG3 SNVs in the same sample were arranged in cis, the BAG3 locus was amplified, cloned into a plasmid, and subjected to Sanger sequencing, as described in the eMethods and eFigure 1 in the Supplement.

Western Blot Analysis and Quantitative PCR of Human Heart Tissue

Protein levels of BAG3 in human failing heart were quantified by Western blot and messenger RNA (mRNA) BAG3 levels were determined by quantitative PCR. This approach has been described previously32 and in the eMethods in the Supplement.

Measurement of Autophagy and Apoptosis in AC16 Cells

Autophagy was measured in transformed human ventricular cells (AC16) that were transfected with plasmids containing either wild-type BAG3 or a BAG3 variant (eTable 2 in the Supplement) and cotransfected with the adenovirus-red fluorescent protein-green fluorescent protein-microtubule–associated protein 1A/1B light chain 3 (Adv-RFP-GFP-LC3) reporter construct, as described in detail in the eMethods in the Supplement and in previous studies.18,33 In a second group of experiments, cells were stained for apoptosis with Annexin-V (Dead Cell Apoptosis kit with AnnexinV Alexa fluoro 488 and propidium iodide; Thermofisher Scientific) and propidium iodide, as described previously34 and in the eMethods in the Supplement.

Measurement of Autophagy in Adult Myocytes Isolated From cBAG3+/− Mice

Cardiac myocytes were isolated from the septum and left ventricular (LV) free wall of male mice aged 10 to 12 weeks who were heterozygotic for the murine version of the constitutive (c) deletion of BAG3 (cBAG3+/−). These cells were infected with an adenovirus containing BAG3wild-type or BAG3p.P63A+P380S, a BAG3 variant having 2 heterozygous SNVs that result in substitution of an alanine for a proline at amino acid 63 and substitution of a serine for a proline at amino acid 380 and an autophagy reporter construct, as described previously18,33 and in the eMethods in the Supplement.

Physiological Associations of a BAG3 Mutation on Left Ventricular Function in cBAG3 + − Mice

To confirm the pathogenicity of the p.P63A+P380S variant in vivo, we generated an adeno-associated virus serotype 9–BAG3p.P63A+P380S and injected 1 × 1012 particles into the retroorbital plexus of cBAG3+/− and cBAG3+/+ mice, as described previously.33,35 Control mice were injected with preparations that included adeno-associated virus 9–green fluorescent protein and adeno-associated virus 9–BAG3wild-type. Mice were examined on follow-up with echocardiography for 6 weeks, as described previously and in the eMethods in the Supplement.36

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted based on stratification or partitioning by BAG3 SNV (SNV vs no SNV), ischemia (ischemic patients vs nonischemic patients), and the concomitant interaction. Continuous variables were assessed using the t test or analysis of variance as appropriate, and categorical variables were assessed using χ2 or Fisher exact tests. For the time-to-event analyses, an event was defined as death, transplant, or HF-associated hospitalization. Survival was assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method; the resulting curves were assessed using the log-rank test. Hazard ratios were estimated using Cox proportional-hazards models. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Statistical significance was defined as P < .05. All reported P values are 2-sided.

Results

BAG3 Genetic Variants

Sanger sequencing of the GRAHF study cohort revealed 18 variants (eTable 3 in the Supplement), 8 of which were synonymous. Four SNVs met the criteria for inclusion in this study: p.Pro63Ala (10:121429369 C/G; rs133031999); p.His83Gln (10:151331972; rs151331972); Pro380Ser (10:121436204 C/T; rs144692954); and Ala479Val (10:121436502 C/T, rs34656239). We also identified a 3-nucleotide in-frame insertion that added an alanine to the protein at position 160 (p.Ala160dup;10:121429647 A/AGCG).

A total of 51 participants carried a BAG3 SNV (10%), and 458 did not (90.0%); this included 42 of 402 individuals (10.4%) with nonischemic heart failure and 9 of 107 individuals (8.4%) with ischemic heart failure. The characteristic demographics of the human cohorts with HF with and without the 4 identified BAG3 variants were not different, as shown in eTable 4 in the Supplement. Briefly, 30 of 51 individuals with BAG3 variants (59%) were male, as were 280 of those without BAG3 variants (61.1%); mean (SD) ages of those with and without the variants were 55.6 (13.4) years and 54.5 (13.6) years, respectively.

Every individual who harbored the p.Pro63Ala variant also carried the p.Pro380Ser variant, and the corresponding allele frequencies for these 2 SNVs in gnomAD were almost identical, suggesting that the 2 SNVs were linked. This was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). The linked SNVs are designated as p.Pro63Ala+Pro380Ser. As seen in eFigure 2 in the Supplement, the amino acids (His83, Ala160, Pro380, and Ala479) affected in the BAG3 variants are highly conserved across mammals.

The prevalence of the 4 BAG3 variants in the 402 patients with IDC in the cohorts from the GRAHF, IMAC-2, and GRACE studies (n = 42; 10.4%) was not greater than the prevalence of the 4 variants in patients with ischemic HF (n = 9 of 107; 8.41%) when adjusted for multiple alleles (Table). Similarly, the proportion of patients in these 3 cohorts with 1 of the 4 BAG3 variants was not significantly different than the proportion of patients of African ancestry with a BAG3 variant in the sum of the corresponding gnomAD data set for each variant (9.06%). In contrast, the proportion of patients in the 3 cohorts who harbored a BAG3 variant (10%) was significantly higher than the prevalence of the 4 BAG3 variants among more than 60 000 individuals of European ancestry in the gnomAD European data set (0.02%; P < .001) and was significantly greater than that of a reference population (collected at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital) of 359 individuals with European ancestry and IDC, of whom 0 individuals had BAG3 variants (P < .001).

Table. Frequency of BAG3 Mutation by Pathology and Data Source.

| Patients per Study Cohort and Pathology Type | No./Total No. (%) | Prevalence, % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients With Variant 63/380a | Patients With Ala160dup | Patients With His83Gln | Patients With Ala479V | Unadjustedc | Adjusted for Multiple Allelesd | |

| GRAHF | ||||||

| Nonischemic | 4/255 (1.6) | 18/249 (7.2) | 9/246 (3.7) | 4/255 (1.6) | 14.0 | 11.4 |

| Ischemic | 0/87 | 6/87 (6.90) | 2/87 (2.3) | 0/87 | 9.2 | 9.2 |

| GRACE | ||||||

| Nonischemic | 1/88 (1.1) | 5/89 (5.6) | 0/89 | 1/88 (1.1) | 7.9 | 7.9 |

| Ischemic | 0/20 | 0/20 | 1/20 (5.0) | 0/19 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| IMAC-2 | ||||||

| Nonischemic | 0/58 | 3/58 (5.2) | 2/58 (3.5) | 1/58 (1.7) | 10.3 | 10.3 |

| All studies | ||||||

| Nonischemic | 5/401 (1.3) | 26/396 (6.6) | 11/393 (2.8) | 6/401 (1.5) | 12.1 | 10.5 |

| Ischemic | 0/107 | 6/107 (5.6) | 3/107 (2.8) | 0/106 | 8.4 | 8.4 |

| Total | 5/508 (0.98) | 32/503 (6.4) | 14/500 (2.8) | 6/507 (1.2) | 11.3 | 10.0 |

| European American reference datae | ||||||

| Nonischemic | 0/359 | 0/359 | 0/359 | 0/359 | 0 | 0 |

| gnomAD population data | ||||||

| Individuals of African ancestry | 263/12 015 (2.19) |

627/11 682 (5.4) |

250/12 015 (2.1) |

76/12 019 (0.63) |

10.3 | 9.1 |

| Individuals of European ancestry | 9/63 271 (0.01) |

0/62 112 | 5/63 345 (0.01) |

0/63 354 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

Abbreviations: gnomAD, the Genome Aggregation Database; GRACE, Genetic Risk Assessment of Cardiac Events; GRAHF, the Genetic Risk Assessment of African Americans With Heart Failure; IMAC-2, Myocarditis and Acute Cardiomyopathy Trial-2.

63/380 is the double heterozygous p.Pro63Ala+p.Pro380Ser BAG3 variant in which both variants are linked in cis.

The percentage of individuals with a given SNV was calculated as the number of individuals with the SNV divided by the number sequenced; not all individuals could be sequenced for every SNV, so the denominator varied by SNV and cohort.

Calculated as the sum of 4 percentages.

Calculated as the total number of individuals with 1 or more SNV, divided by the total number of individuals in that cohort.

These reference data are from the Brigham and Women’s Hospital data set.

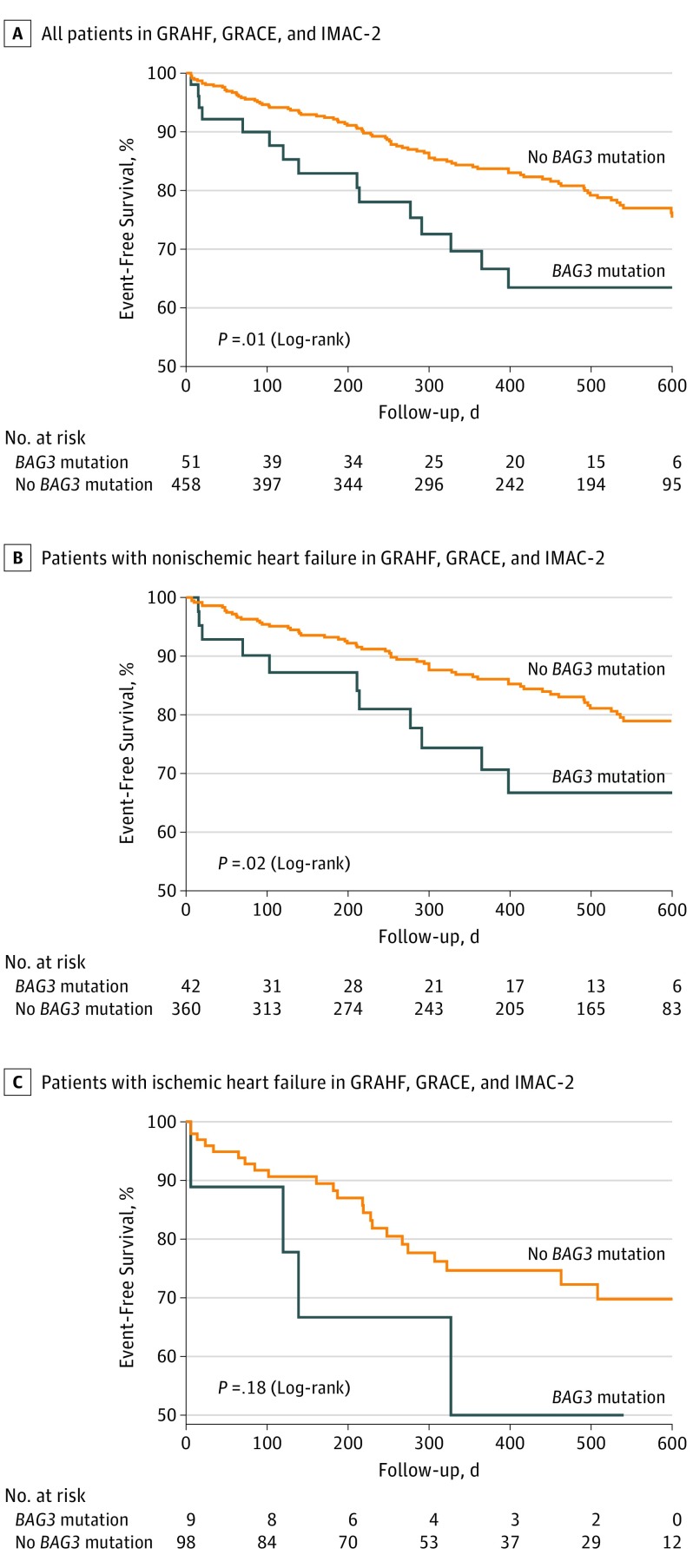

Association of BAG3 Variants With Heart Failure Outcomes

We next sought to determine whether the presence of any 1 of the 4 BAG3 variants was associated with a worse outcome, as reflected by the combined outcome variable of an HF hospitalization, heart transplant, or death. As seen in Figure 1A, when compared with patients with HF with either ischemic or nonischemic disease who did not carry 1 of the 4 BAG3 variants (n = 458), patients who had a BAG3 variant (n = 51) had a significantly (83 events in 458 patients [18.1%] vs 15 events in 51 patients [29.4%]; P = .01) higher incidence of an adverse event. Similarly, individuals with nonischemic HF who carried a BAG3 variant had a worse outcome compared with patients with nonischemic disease who did not have a BAG3 variant (Figure 1B; 11 events in 42 patients [26.1%]; P = .02). In patients with ischemic HF and a BAG3 SNV, outcomes were not significantly worse (Figure 1C); 4 of the 98 patients without a mutation experienced an event (4.1%), while 4 of the 9 patients with a mutation had an event (44.4%; P = .18).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Curves Showing Event-Free Survival in Patients With or Without a BAG3 Genetic Variant.

Kaplan-Meier curves show event-free survival in all patients (A), patients with nonischemic heart failure (B), and patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (C), with or without a BAG3 variant. GRACE indicates the Genetic Risk Assessment of Cardiac Events trial; GRAHF, the Genetic Risk Assessment of African Americans With Heart Failure trial; IMAC-2, Myocarditis and Acute Cardiomyopathy Trial-2.

Using a 2-variable Cox proportional hazard analysis (BAG3 variant and ischemic HF), we determined that the risk of a carrier of 1 of the 4 BAG3 variants having an adverse event was 1.97 times higher than for an individual with HF who did not have a BAG3 variant (hazard ratio, 1.97 [95% CI, 1.19-3.24]; P = .01), and that the risk of an individual with ischemic HF having an adverse event was 1.76 times higher than the risk of an individual with nonischemic HF (hazard ratio, 1.76 [95% CI, 1.18-2.60]; P = .01). Based on additional modeling using a 3-term Cox proportional hazard analysis (BAG3 variant, ischemic HF, and the interaction between these 2 variables), the interaction between the BAG3 variant and ischemic HF variables was not statistically significant.

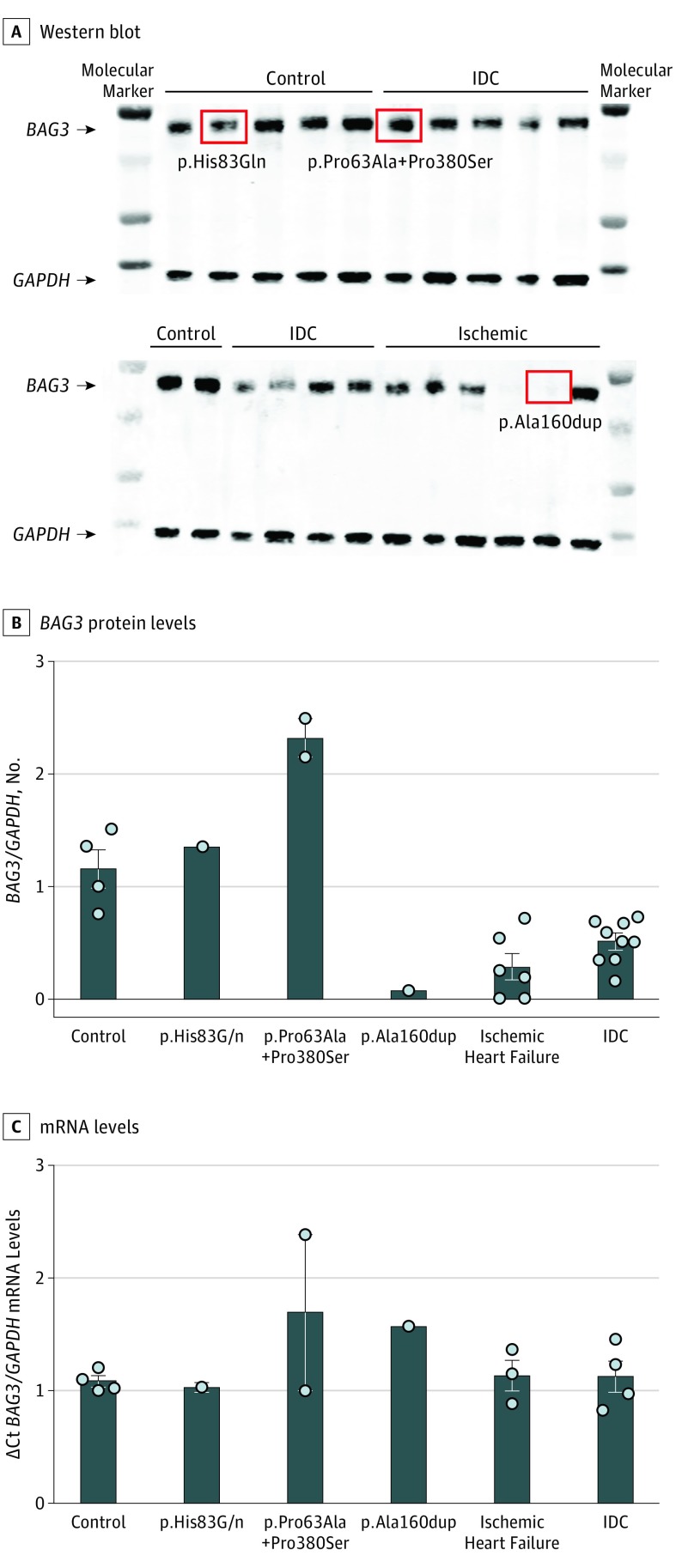

BAG3 Levels in Failing Human Heart

Western blot analysis of BAG3 protein levels and quantitative PCR to quantify BAG3 mRNA were performed in failing human hearts from participants of African ancestry and nonfailing hearts from control participants of African ancestry (cohorts from the University of Colorado and University of Pittsburgh). As we reported previously in a cohort of individuals of largely European ancestry,32 BAG3 levels were significantly reduced in hearts extracted from transplant recipients who had IDC (n = 23; P = .001) or ischemic HF (n = 16; P < .001) compared with control participants with nonfailing hearts (n = 4; Figure 2A and B). By contrast, BAG3 mRNA levels from the hearts of patients with IDC (n = 18) and from the hearts of patients with ischemic DCM (n = 13) were not different from those of control participants (n = 4; Figure 2C). The levels of BAG3 protein were higher than normal in the 2 hearts of patients with p.Pro63Ala+Pro380Ser variants and were unchanged in the heart of the patient with a p.His83Gln variant. By contrast, the level of BAG3 protein in the heart of a patient harboring the p.Ala160dup variant was comparable with levels seen in the patients without BAG3 variants.

Figure 2. Levels of BAG3 Protein and Messenger RNA (mRNA) in Failing Human Hearts.

A, A representative Western blot of protein isolated from human hearts with severe left ventricular dysfunction secondary to idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (IDC; n = 23) or ischemic heart disease (n = 16), contrasted with control participants with nonfailing hearts (n = 4). Samples obtained from hearts that were found to carry a BAG3 variant are indicated by the red squares. The unlabeled lanes represent molecular weight markers. B, Quantification of multiple Western blots. C, Quantification of quantitative polymerase chain reaction assessment of mRNA levels in a subset of the same hearts (non-IDC, n = 13; IDC, n = 18; and nonfailing human hearts from control participants, n = 4). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) served as an internal control for both the Western blot and the quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

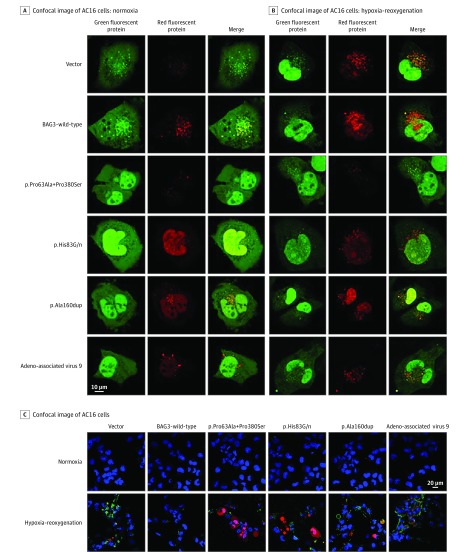

Pathogenicity of BAG3 Variants

We next undertook studies to assess the association of BAG3 variants with the 2 primary actions of BAG3 protein in the cell: autophagy and apoptosis. As seen in Figure 3A and eFigure 3 in the Supplement, when AC16 cells were transfected with either the empty plasmid or with wild-type BAG3, there was a significant increase in autophagy in response to hypoxia-reoxygenation; however, the autophagy response to hypoxia-reoxygenation was significantly diminished in AC16 cells that overexpress each of the 4 BAG3 variants, because there was no significant increase in the LC3 reporter construct (Figure 3A and eFigure 3 in the Supplement). In addition, after hypoxia-reoxygenation, cells transfected with BAG3 variants showed significantly more Annexin-V–positive cells than did cells transfected with a plasmid expressing wild-type BAG3 (Figure 3B and eFigure 3 in the Supplement). Thus, by contrast with wild-type BAG3, the BAG3 variants were unable to impede hypoxia-induced apoptosis. To demonstrate that the measurement of autophagy in the presence of the different BAG3 variants was not compromised by variable levels of expression of each variant, the plasmids containing wild-type BAG3 and each BAG3 variant were transduced into AC16 cells. Each BAG3 variant was tagged with myc, which allowed endogenous BAG3 to be separated from transduced BAG3 by assessing the levels of myc. The levels of myc appeared comparable across all plasmids (eFigure 4 in the Supplement).

Figure 3. Confocal Images of Autophagy Flux and Apoptosis in AC16 Cells.

Representative confocal images from AC16 cells that were transfected with an empty plasmid or one containing wild-type BAG3 or c.187C→G+c.1138C→T (p.Pro63Ala + p.Pro380Ser), c.249C→A (p.His83Gln), c.474_476dupGGC (p.Ala160dup), or c.1436C→T (p.Ala479Val) and then cotransfected with adenovirus-red fluorescent protein-green fluorescent protein-microtubule–-associated protein 1A/1B light chain 3. A, Red puncta represent increased LC3 in autophagolysosomes in which green fluorescent protein has been quenched by the increased acidity after lysosomal-autophagasome fusion. B, Hypoxia-reoxygenation increased autophagy in cells with empty vectors or wild-type BAG3, as seen by an increase in yellow-red LC3 puncta; expression of any BAG3 variants resulted in impaired autophagy response and a diminished increase in total LC3 puncta compared with wild-type BAG3. C, A representative confocal image of AC16 cells stained with Annexin-V (green) and propidium iodide (red) to distinguish apoptotic cells (green), late apoptotic and necrotic cells (red), and nonviable cells (green and red). Few apoptotic cells are seen in AC16 cells transfected with wild-type BAG3; there was a marked increase in apoptotic cells in the presence of an empty vector or any BAG3 variant.

Because AC16 cells are transformed and thus might not adequately represent cardiac myocytes, we confirmed these findings using adult myocytes isolated from cBAG3+/− mice. When lysosome-autophagosome fusion was inhibited by the addition of bafilomycin A1, there was a marked increase in total LC3 reporter construct in cBAG3+/− myocytes transfected with Adenovirus-BAG3wild-type (Adv-BAG3wild-type; eFigure 5 in the Supplement), suggesting that autophagy was occurring. By contrast, transfection with Adv-BAG3P63A+P380S had no significant effect on LC3 reporter construct levels, suggesting that the variant could not support autophagy. In the heterozygous BAG3 knockout mouse, autophagasome production is so low that blockade of autophagasome-lysosome fusion is associated with little change in the abundance of LC3, whereas restitution of normal BAG3 levels increases the amount of autophagy.

When the adult cBAG3+/− myocytes were stained for apoptosis, there were significantly fewer apoptotic cells when the cells were infected with Adv-BAG3wild-type than when the cells were infected with either Adv-null (an empty vector) or Adv-BAG3p.P380A+P380S (eFigure 6 in the Supplement). By contrast with AC16 cells, we did not use hypoxia and reoxygenation to induce apoptosis in the cBAG3+/− cells, because under the culture conditions used, the loss of a single BAG3 allele led to a marked intolerance to even modest amounts of hypoxia, thereby making it difficult to find live cells after this process was initiated.

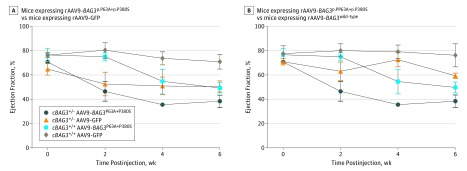

To further confirm the findings in AC16 cells, we administered adeno-associated virus 9 (rAAV9)-BAG3wild-type or rAAV9-green fluorescent protein (GFP) by retroorbital injection to cBAG3+/− mice aged 8 to 10 weeks. As shown in Figure 4A, infection with rAAV9-BAG3wild-type did not alter the ejection fraction (EF) of mice homozygous for cBAG3 (n = 3) with a normal complement of BAG3 (mean [SD] EF, 76.3% [9.5%]) compared with mice transfected with rAAV9-GFP (71.0% [6.1%]). However, consistent with results in AC16 cells, administration of rAAV9-BAG3p.P63A+p.P380S significantly (P = .05) reduced the EF (mean [SD] EF, 49.7% [4.4%]) compared with the outcomes of AAV9-GFP or AAV9-BAG3wild-type, suggesting that the p.P63A+p.P380S variant has a dominant-negative effect. By contrast, in mice with haploinsufficiency of BAG3, mice with wild-type BAG3 (n = 4) improved left ventricular function (mean [SD] function, 59.4% [2.2%]) when compared with mice in the rAAV9-GFP group (n = 4; 50.5% [4.6%]). Consistent with results in mice with a full complement of BAG3, infection with rAAV9-BAG3p.P63A+p.P380S reduced the EF in mice who were heterozygous for cBAG3 (n = 4; mean [SD] EF, 38.6% [5.1%]; P = .05) compared with mice who were heterozygous for cBAG3 who were infected with rAAV9-BAG3wild-type. In aggregate, these results were consistent with the observations in AC16 cells. Furthermore, these results could not be explained by differences in the level of BAG3 expression that were comparable across all groups (eFigure 7 in the Supplement).

Figure 4. Hemodynamic Effects of Infection With rAAV9-BAG3 vs rAAV9-BAG3p.P63A+P380S in Mice With BAG3 Haploinsufficiency (cBAG3+/−) or in Nontransgenic Wild-Type Mice (cBAG3+/+).

cBAG3+/− mice aged 4 to 6 weeks received either a retro-orbital injection of 1x1012 particles of adeno-associated virus 9 (rAAV9)–BAG3p.P63A+P380S, rAAV9-green fluorescence protein (GFP) or rAAV9-BAG3wild-type and were then given echocardiograms every other week. In the same experiment, 6-week-old cBAG3+/+ mice received an injection of either rAAV9-BAG3p.P63A+P380S, rAAV9-GFP, or rAAV9-BAG3wild-type. After 6 weeks, left ventricular myocardium was harvested for subsequent analysis. A, A comparison of serial measures of left ventricular ejection fraction by echocardiogram in mice infected with the rAAV9-BAG3p.P63A+P380S (cBAG3+/+: n = 4; cBAG3+/−: n = 3) with mice infected with rAAV9-GFP (cBAG3+/+: n = 8; cBAG3+/−: n = 4) shows statistical significant differences at 2, 4, and 6 weeks (P = .01). B, A comparison of mice infected with the rAAV9-BAG3p.P63A+P380S (cBAG3+/+: n = 4; cBAG3+/−: n = 3) with mice expressing rAAV9-BAG3wild-type (cBAG3+/+: n = 4; cBAG3+/−: n = 5) shows statistically significant differences at 4 and 6 weeks (P = .05).

Discussion

BAG3 is an evolutionarily conserved protein that is expressed largely in the heart and the skeletal muscle.37 Its importance lies in its regulation of important cellular functions, including protein quality control, apoptosis, and excitation/contraction coupling.17 Genetic variants in BAG3, including deletions, truncations, and SNVs, have met the criteria for causation of familial DCM.38 The levels of BAG3 are reduced in families with DCM and BAG3 truncations or deletions32,39 and individuals with nonfamilial end-stage HF.32,39 The levels of BAG3 are also reduced in mice with haploinsufficiency of BAG318 and in animal models of LV dysfunction.17,35 In the present study, we identified a group of relatively common genetic variants (presented in more than 1% of individuals); 2 nonsynonymous SNVs, a 3-nucleotide in-frame insertion, and 2 linked SNVs. The 4 variants were found equally in African American individuals with nonischemic DCM and ischemic DCM, as well as in African American individuals without known cardiovascular disease. However, these variants were largely absent in individuals of European ancestry with or without HF. Most importantly, the presence of any 1 of the 4 variants was associated with a nearly 2-fold increase in the risk of death or HF hospitalization. Thus, while they were not a disease-initiating factor, these variants were significantly associated with modified response to disease.

Although it is axiomatic that large deletions or truncations of a protein will significantly alter the protein’s function, the physiologic effect of SNVs is often far less obvious. That the 4 variants have functional significance in the heart was demonstrated by the fact that each altered both autophagy and apoptosis when transfected into AC16 cells. The relevance of the changes in the AC16 cells was supported by the finding that the variant that combines p.Pro63Ala with p.Pro380Ser was unable to support LV function in mice with haploinsufficiency of BAG3 as evidenced by a significant decrease in the EF in adult myocytes isolated from cBAG3+/+ and cBAG3+/- mice that were infected with rAAV9-BAG3p.P63A+p.P380S. Fang et al40 have recently shown that when a human SNV (E455K) is knocked into mice, the resulting progeny have a loss of BAG3 function and develop dilated cardiomyopathy; however, they only found this phenotype in mice with homozygosity.

Interestingly, the 4 variants identified in this study were annotated by ClinVar41 as benign (p.Pro63Ala), benign or likely benign (p.Ala160dup; p.Pro380Ser), or with indeterminate pathogenicity (p.His83Gln and p.Ala479Val). The finding that each of these is pathogenic when evaluated in a biologic system emphasizes the lack of specificity of in silico pathogenicity prediction algorithms and the use of enhanced software and computational predictions in determining pathogenicity and providing annotation for SNVs.42

The variants identified in the present study have not been recognized previously in cohorts of probands with familial DCM. This is likely because of the paucity of African American individuals in genetic studies of HF. For example, in 4 studies20,38,43,44 that identified BAG3 variants in independent index cases with familial DCM, fewer than 16 participants in aggregate were identified as individuals of African ancestry. In a large exome-wide array-based association study, investigators identified a BAG3 locus (c.451T→C, p.Cys151Arg) that conferred a reduced risk of DCM. Although we found the same variant in this study population, the variant is very common in populations of European ancestry (0.2163 allele frequency) and African ancestry (0.03 allele frequency) and therefore did not meet the criteria for inclusion in the present analysis.31 The absence of racial/ethnic minority participants in genetic studies is an important disparity in cardiovascular research that needs to be addressed.45

Conclusions

In conclusion, unique variants in BAG3 found almost exclusively in individuals of African descent were not associated with the onset of DCM but were associated with a negative influence on the phenotypic response to the development of DCM and worse outcomes of patients with both ischemic and nonischemic disease. This study raises several points that are relevant to our understanding of the genetics of HF. First, biological differences should be considered along with environmental and social factors as important in understanding phenotypic differences across diverse patient populations.46 Second, we cannot fully understand population-based differences without enhancing the diversity of the populations that are included in genomic studies.45,47,48 Third, evidence supporting pathogenicity of these SNVs would be strengthened by a prospective study and an understanding of possible familial recurrence and/or segregation. Finally, in the era of big data, it is important to sometimes take a reductionist approach until such time as computer algorithms have the same efficacy as biological measurements for ascertaining the functional effects of SNVs.

eMethods.

eTable 1. Primers used for BAG3 exon sequencing.

eTable 2. Primers used for generation of BAG3 variant plasmids.

eTable 3. Sequencing results.

eTable 4. Patient Demographics.

eReferences.

eFigure 1. Determination of linked variants.

eFigure 2. Conservation of BAG3 variant sites.

eFigure 3. Quantification of autophagy and apoptotic cell death in AC16 cells with BAG3 variant expression.

eFigure 4. Plasmid expression in AC16 cells.

eFigure 5. Autophagy in adult ventricular cardiomyocytes expressing P63A + P380S BAG3 expression.

eFigure 6. Apoptotic cell death in adult ventricular cardiomyocytes expressing P63A + P380S BAG3 expression.

eFigure 7. BAG3 protein levels in BAG3+/+ and cBAG3+/- mice transduced with AAV9-GFP or AAV9-BAG3p.P63A+P380S.

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. ; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(10):e146-e603. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yancy CW. Heart failure in African Americans: a cardiovascular enigma. J Card Fail. 2000;6(3):183-186. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2000.17610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loehr LR, Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Folsom AR, Chambless LE. Heart failure incidence and survival (from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study). Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(7):1016-1022. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.11.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Echols MR, Felker GM, Thomas KL, et al. Racial differences in the characteristics of patients admitted for acute decompensated heart failure and their relation to outcomes: results from the OPTIME-CHF trial. J Card Fail. 2006;12(9):684-688. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bahrami H, Kronmal R, Bluemke DA, et al. Differences in the incidence of congestive heart failure by ethnicity: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(19):2138-2145. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.19.2138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dries DL, Exner DV, Gersh BJ, Cooper HA, Carson PE, Domanski MJ. Racial differences in the outcome of left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(8):609-616. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902253400804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeboah J, Rodriguez CJ, Stacey B, et al. Prognosis of individuals with asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation. 2012;126(23):2713-2719. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.112201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sliwa K, Wilkinson D, Hansen C, et al. Spectrum of heart disease and risk factors in a black urban population in South Africa (the Heart of Soweto study): a cohort study. Lancet. 2008;371(9616):915-922. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60417-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bibbins-Domingo K, Pletcher MJ, Lin F, et al. Racial differences in incident heart failure among young adults. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(12):1179-1190. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosamond W, Johnson A. Is home where the heart is? the role of neighborhood in heart failure risk. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(1):e004455. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.004455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carnethon MR, Pu J, Howard G, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology; and Stroke Council . Cardiovascular health in African Americans: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;136(21):e393-e423. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Damasceno A, Mayosi BM, Sani M, et al. The causes, treatment, and outcome of acute heart failure in 1006 Africans from 9 countries. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1386-1394. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ntusi NB, Mayosi BM. Epidemiology of heart failure in sub-Saharan Africa. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2009;7(2):169-180. doi: 10.1586/14779072.7.2.169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herman DS, Lam L, Taylor MR, et al. Truncations of titin causing dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(7):619-628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ware JS, Seidman JG, Arany Z. Shared genetic predisposition in peripartum and dilated cardiomyopathies. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(26):2601-2602. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1602671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Behl C. Breaking BAG: the co-chaperone BAG3 in health and disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2016;37(8):672-688. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2016.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knezevic T, Myers VD, Gordon J, et al. BAG3: a new player in the heart failure paradigm. Heart Fail Rev. 2015;20(4):423-434. doi: 10.1007/s10741-015-9487-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Myers VD, Tomar D, Madesh M, et al. Haplo-insufficiency of Bcl2-associated athanogene 3 in mice results in progressive left ventricular dysfunction, β-adrenergic insensitivity, and increased apoptosis. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(9):6319-6326. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franaszczyk M, Bilinska ZT, Sobieszczańska-Małek M, et al. The BAG3 gene variants in Polish patients with dilated cardiomyopathy: four novel mutations and a genotype-phenotype correlation. J Transl Med. 2014;12:192. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-12-192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chami N, Tadros R, Lemarbre F, et al. Nonsense mutations in BAG3 are associated with early-onset dilated cardiomyopathy in French Canadians. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30(12):1655-1661. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.09.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, et al. ; Exome Aggregation Consortium . Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536(7616):285-291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor AL, Ziesche S, Yancy C, et al. ; African-American Heart Failure Trial Investigators . Combination of isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine in blacks with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(20):2049-2057. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNamara DM, Tam SW, Sabolinski ML, et al. Aldosterone synthase promoter polymorphism predicts outcome in African Americans with heart failure: results from the A-HeFT Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(6):1277-1282. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McNamara DM, Tam SW, Sabolinski ML, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (NOS3) polymorphisms in African Americans with heart failure: results from the A-HeFT trial. J Card Fail. 2009;15(3):191-198. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2008.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McNamara DM, Taylor AL, Tam SW, et al. G-protein beta-3 subunit genotype predicts enhanced benefit of fixed-dose isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine: results of A-HeFT. JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2(6):551-557. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2014.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNamara DM, Starling RC, Cooper LT, et al. ; IMAC Investigators . Clinical and demographic predictors of outcomes in recent onset dilated cardiomyopathy: results of the IMAC (Intervention in Myocarditis and Acute Cardiomyopathy)-2 study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(11):1112-1118. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.05.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McNamara DM, Holubkov R, Janosko K, et al. Pharmacogenetic interactions between beta-blocker therapy and the angiotensin-converting enzyme deletion polymorphism in patients with congestive heart failure. Circulation. 2001;103(12):1644-1648. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.12.1644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McNamara DM, Holubkov R, Postava L, et al. Pharmacogenetic interactions between angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy and the angiotensin-converting enzyme deletion polymorphism in patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(10):2019-2026. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNamara DM, Holubkov R, Starling RC, et al. Controlled trial of intravenous immune globulin in recent-onset dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2001;103(18):2254-2259. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.18.2254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bristow MR, Minobe WA, Raynolds MV, et al. Reduced beta 1 receptor messenger RNA abundance in the failing human heart. J Clin Invest. 1993;92(6):2737-2745. doi: 10.1172/JCI116891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Esslinger U, Garnier S, Korniat A, et al. Exome-wide association study reveals novel susceptibility genes to sporadic dilated cardiomyopathy. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0172995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feldman AM, Begay RL, Knezevic T, et al. Decreased levels of BAG3 in a family with a rare variant and in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Cell Physiol. 2014;229(11):1697-1702. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Su F, Myers VD, Knezevic T, et al. Bcl-2-associated athanogene 3 protects the heart from ischemia/reperfusion injury. JCI Insight. 2016;1(19):e90931. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.90931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dong Z, Shanmughapriya S, Tomar D, et al. Mitochondrial ca2+ uniporter is a mitochondrial luminal redox sensor that augments MCU channel activity. Mol Cell. 2017;65(6):1014-1028.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.01.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knezevic T, Myers VD, Su F, et al. Adeno-associated virus serotype 9 - driven expression of bag3 improves left ventricular function in murine hearts with left ventricular dysfunction secondary to a myocardial infarction. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2016;1(7):647-656. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2016.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li X, Chan TO, Myers V, et al. Controlled and cardiac-restricted overexpression of the arginine vasopressin V1A receptor causes reversible left ventricular dysfunction through Gαq-mediated cell signaling. Circulation. 2011;124(5):572-581. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.021352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Behl C. BAG3 and friends: co-chaperones in selective autophagy during aging and disease. Autophagy. 2011;7(7):795-798. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.7.15844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Norton N, Li D, Rieder MJ, et al. Genome-wide studies of copy number variation and exome sequencing identify rare variants in BAG3 as a cause of dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(3):273-282. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toro R, Pérez-Serra A, Campuzano O, et al. Familial dilated cardiomyopathy caused by a novel frameshift in the BAG3 gene. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0158730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fang X, Bogomolovas J, Wu T, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in co-chaperone BAG3 destabilize small HSPs and cause cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(8):3189-3200. doi: 10.1172/JCI94310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Riley GR, et al. ClinVar: public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D980-D985. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mueller SC, Backes C, Haas J, et al. ; INHERITANCE Study Group . Pathogenicity prediction of non-synonymous single nucleotide variants in dilated cardiomyopathy. Brief Bioinform. 2015;16(5):769-779. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbu054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Villard E, Perret C, Gary F, et al. ; Cardiogenics Consortium . A genome-wide association study identifies two loci associated with heart failure due to dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(9):1065-1076. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Franceschelli S, Rosati A, Lerose R, De Nicola S, Turco MC, Pascale M. Bag3 gene expression is regulated by heat shock factor 1. J Cell Physiol. 2008;215(3):575-577. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gerhard GS, Fisher SG, Feldman AM. Genetic testing for inherited cardiac diseases in underserved populations of non-European ancestry: double disparity. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(4):273-274. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.5345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor AL. Racial differences and racial disparities: the distinction matters. Circulation. 2015;131(10):848-850. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dellefave-Castillo LM, Puckelwartz MJ, McNally EM. Reducing racial/ethnic disparities in cardiovascular genetic testing. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(4):277-279. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.5382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Landry LG, Rehm HL. Association of racial/ethnic categories with the ability of genetic tests to detect a cause of cardiomyopathy. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(4):341-345. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.5333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods.

eTable 1. Primers used for BAG3 exon sequencing.

eTable 2. Primers used for generation of BAG3 variant plasmids.

eTable 3. Sequencing results.

eTable 4. Patient Demographics.

eReferences.

eFigure 1. Determination of linked variants.

eFigure 2. Conservation of BAG3 variant sites.

eFigure 3. Quantification of autophagy and apoptotic cell death in AC16 cells with BAG3 variant expression.

eFigure 4. Plasmid expression in AC16 cells.

eFigure 5. Autophagy in adult ventricular cardiomyocytes expressing P63A + P380S BAG3 expression.

eFigure 6. Apoptotic cell death in adult ventricular cardiomyocytes expressing P63A + P380S BAG3 expression.

eFigure 7. BAG3 protein levels in BAG3+/+ and cBAG3+/- mice transduced with AAV9-GFP or AAV9-BAG3p.P63A+P380S.