Abstract

This cohort study examines 57 Colombian patients with thyroid nodules classified as Bethesda categories V to VI who were treated with active surveillance.

The incidence of thyroid carcinoma is growing worldwide owing to overdiagnosis.1 Japanese authors have shown that active surveillance of patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma is possible.2 Some case series have recently been published in Western countries,3 but there are no reports from Latin America. The aim of this study is to report and describe a cohort of patients with thyroid nodules classified as Bethesda categories V to VI and who are under active surveillance.

Methods

This is a report of a prospective cohort from a head and neck cancer center in Medellín, Colombia. All patients were referred to the author as potential candidates for thyroidectomy. Local institutional review board authorization was provided, and written informed consent was waived due to the descriptive character of the study. All had thyroid nodules found in ultrasonographic imaging with fine-needle aspiration biopsy results classified as Bethesda categories V to VI. An active surveillance trial was proposed to patients with low-risk microcarcinoma (<1.5 cm, encapsulated, without evidence of lymph node metastasis) following Japanese and American recommendations2,3 (periodic evaluation with ultrasound, immediate consultation if clinical symptoms or lymph nodes appeared, centralized management of the disease, immediate surgery if a significant growth occurred, patient preference). Only patients who accepted the strategy are reported in this study. Data on age, sex, reason for an ultrasound examination, ultrasound risk by American Thyroid Association (ATA) classification, size of the nodule, reason to consider active surveillance and follow-up ultrasounds, and surgical decision were recorded prospectively. A Kaplan-Meier graph was built for stability of the nodule without any growth, without growth more than 3 mm, and need of operation.

Results

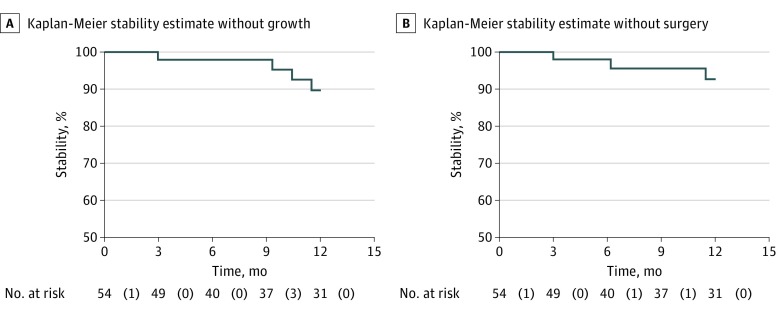

A total of 57 patients were analyzed since September 2013. Mean (SD) age was 51.9 (14.5) years (range, 24-85 years). Forty-eight (84%) of the 57 patients were women, and in 55 (96%) the nodule was incidentally discovered. Mean (SD) and median nodule size was 9.7 (4.3) mm and 9 mm (range, 3-26 mm), respectively. Only 9 of 57 (16%) nodules were classified as ATA low risk, whereas 36 (61%) nodules were classified as Bethesda category V. Of the 57 patients, 14 (25%) explicitly expressed the desire for surveillance, and in 36 (63%) patients the proposal of surveillance was based on a nodule size smaller than 1 cm. The median number of follow-up visits was 2 (range, 0-6). Median follow-up was 13.3 months (range, 0-54 months). Of 57 nodules, 16 (28%) grew a mean (SD) of 2 (1.3) mm, but only 2 (3.5%) grew more than 3 mm. Five of 57 (9%) patients underwent surgery (3 owing to nodule growth and 2 for other reasons). All of them had a papillary carcinoma treated with lobectomy. The overall stability rate without growth (Figure, A), without growth more than 3 mm, and without surgery (Figure, B) at 12 months was 90%, 98%, and 92.5%, respectively.

Figure. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves of Malignant and Suspicious Thyroid Nodules Under Active Surveillance.

A, Overall stability rate without growth. B, Overall stability rate without surgery. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of failures.

Discussion

Overdiagnosis in thyroid cancer is an important problem.4 As the number of incident cases increases, the possibility of harm related to treatment also increases. Most of the new cases are subcentimeter nodules incidentally found by an imaging test, which are biopsied and have high malignancy suspicion.1 Most of these nodules will not have any detrimental effect on survival, but today, such patients often undergo thyroidectomy. As an alternative, active surveillance protocols are safe in selected cases, avoiding the risks associated with surgery. There are studies on patients in Asia and the United States, but not in Latin America to our knowledge. Some authors have suggested that there are obstacles to surveillance, including physician responsibility (surgeons are not able to do it), physician reimbursement, and patient anxiety,5 that are frequent in developing countries, but these may be solved with education, new health policies, and training. Major barriers to implementation of surveillance of patients include home located in remote rural areas and lack of insurance, which together impede routine imaging and medical follow-up; patients’ low educational level, which impedes understanding of risks and benefits of surveillance; fear on the part of physicians of future legal actions; and resistance to change. This cohort study demonstrates that this approach is feasible in Latin America.

References

- 1.Davies L, Welch HG. Current thyroid cancer trends in the United States. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140(4):317-322. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ito Y, Miyauchi A, Oda H. Low-risk papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid: a review of active surveillance trials. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44(3):307-315. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2017.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tuttle RM, Fagin JA, Minkowitz G, et al. Natural history and tumor volume kinetics of papillary thyroid cancers during active surveillance. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143(10):1015-1020. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2017.1442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanabria A, Kowalski LP, Shah JP, et al. Growing incidence of thyroid carcinoma in recent years: Factors underlying overdiagnosis. Head Neck. 2018;40(4):855-866. doi: 10.1002/hed.25029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haymart MR, Miller DC, Hawley ST. Active surveillance for low-risk cancers—a viable solution to overtreatment? N Engl J Med. 2017;377(3):203-206. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1703787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]