This randomized clinical trial reports that 5-year visual acuity results were similar in patients treated with panretinal photocoagulation and ranibizumab for proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Key Points

Question

What is the comparative efficacy and safety of intravitreous ranibizumab vs panretinal photocoagulation over 5 years for treatment of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 305 participants, although loss to follow-up was relatively high, visual acuity in most study eyes that completed follow-up was very good at 5 years, consistent with 2-year results. Severe vision loss or serious proliferative diabetic retinopathy complications were uncommon in either group; the ranibizumab group had lower rates of developing vision-impairing diabetic macular edema.

Meaning

These findings support either ranibizumab or panretinal photocoagulation as viable treatments for proliferative diabetic retinopathy; patient-specific factors, including anticipated visit compliance, cost, and frequency of visits, should be considered when choosing a treatment for patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Abstract

Importance

Ranibizumab is a viable treatment option for eyes with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) through 2 years. However, longer-term results are needed.

Objective

To evaluate efficacy and safety of 0.5-mg intravitreous ranibizumab vs panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) over 5 years for PDR.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network multicenter randomized clinical trial evaluated 394 study eyes with PDR enrolled February through December 2012. Analysis began in January 2018.

Interventions

Eyes were randomly assigned to receive intravitreous ranibizumab (n = 191) or PRP (n = 203). Frequency of ranibizumab was based on a protocol-specified retreatment algorithm. Diabetic macular edema could be managed with ranibizumab in either group.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Mean change in visual acuity (intention-to-treat analysis) was the main outcome. Secondary outcomes included peripheral visual field loss, development of vision-impairing diabetic macular edema, and ocular and systemic safety.

Results

The 5-year visit was completed by 184 of 277 participants (66% excluding deaths). Of 305 enrolled participants, the mean (SD) age was 52 (12) years, 135 (44%) were women, and 160 (52%) were white. For the ranibizumab and PRP groups, the mean (SD) number of injections over 5 years was 19.2 (10.9) and 5.4 (7.9), respectively; the mean (SD) change in visual acuity letter score was 3.1 (14.3) and 3.0 (10.5) letters, respectively (adjusted difference, 0.6; 95% CI, −2.3 to 3.5; P = .68); the mean visual acuity was 20/25 (approximate Snellen equivalent) in both groups at 5 years. The mean (SD) change in cumulative visual field total point score was −330 (645) vs −527 (635) dB in the ranibizumab (n = 41) and PRP (n = 38) groups, respectively (adjusted difference, 208 dB; 95% CI, 9-408). Vision-impairing diabetic macular edema developed in 27 and 53 eyes in the ranibizumab and PRP groups, respectively (cumulative probabilities: 22% vs 38%; hazard ratio, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.3-0.7). No statistically significant differences between groups in major systemic adverse event rates were identified.

Conclusions and Relevance

Although loss to follow-up was relatively high, visual acuity in most study eyes that completed follow-up was very good at 5 years and was similar in both groups. Severe vision loss or serious PDR complications were uncommon with PRP or ranibizumab; however, the ranibizumab group had lower rates of developing vision-impairing diabetic macular edema and less visual field loss. Patient-specific factors, including anticipated visit compliance, cost, and frequency of visits, should be considered when choosing treatment for patients with PDR. These findings support either anti–vascular endothelial growth factor therapy or PRP as viable treatments for patients with PDR.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01489189

Introduction

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) is the leading cause of blindness among working age adults in the United States, contributing 12 000 to 24 000 new cases each year.1,2 Panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) has been the standard treatment for patients with PDR since the 1970s. However, intravitreous anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) injections have emerged as an alternative to PRP for PDR management.3,4 Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network (DRCR.net) Protocol S results demonstrated that mean change in visual acuity (VA) at 2 years with ranibizumab was comparable with PRP and that ranibizumab treatment produced superior VA results over 2 years based on an area under the curve analysis, a lower incidence of vision-impairing diabetic macular edema (DME), fewer vitrectomies, and less peripheral visual field loss.4,5 Five-year results from the Protocol S cohort are reported herein.

Methods

The study took place between February 2012 and February 2018, and analysis began in January 2018. Study procedures and statistical methods, which were reported previously, are summarized. The protocol is available on the DRCR.net website6 and in Supplement 1. The statistical analysis plan is available in Supplement 2. The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki7 and was approved by multiple institutional review boards. Study participants provided written informed consent. An independent data and safety monitoring committee provided oversight.

Fifty-five US clinical sites enrolled 394 study eyes from 305 adults with PDR, no prior PRP, and best-corrected VA letter score of 24 or better (approximate Snellen equivalent 20/320 or better). Eyes with or without central-involved DME were eligible; 88 eyes (22%) at baseline had visual impairment (20/32 or worse) from DME based on optical coherence tomography results. Study eyes were randomly assigned 1:1 to 0.5-mg intravitreous ranibizumab (n = 191) or PRP (n = 203). Participants with 2 study eyes randomly received PRP in 1 eye and ranibizumab in the other.

Eyes in the ranibizumab group received a baseline injection and monthly injections through week 24, with deferral of injections allowed at weeks 16 and 20 if neovascularization (NV) had resolved based on investigator assessment. Beginning at 24 weeks, injections continued if NV improved or worsened but could be deferred if the investigator judged all NV to be resolved or NV became and remained stable after 2 consecutive injections. If NV subsequently worsened, injections were resumed. If an eye met protocol-specified failure or futility criteria, PRP was permitted. Eyes assigned to PRP were treated at baseline with either full PRP or PRP completed over several sittings. Additional PRP was performed if the size or amount of NV increased during follow-up. Vitrectomy for vitreous hemorrhage could not be performed for at least 8 weeks after onset, while vitrectomy for retinal detachment was at investigator discretion. Ranibizumab injections for DME were required in both groups at baseline and could be performed at investigator discretion thereafter.

The study originally required visits every 16 weeks in both groups through 3 years; participants in the ranibizumab group also had visits every 4 weeks during year 1 and every 4 to 16 weeks thereafter depending on treatment course. The study was amended on January 12, 2015, after all participants were enrolled to allow for assessment visits every 16 weeks in both groups and continued study injections and visits every 4 to 16 weeks through 5 years in the ranibizumab group based on the study retreatment algorithm. Among the 238 participants who had a visit after the institutional review board approved the protocol revision, 230 (97%) consented to continue the structured protocol through 5 years. Procedures performed at these visits and image and visual field grading were the same as previously reported.4 Participants were dropped from the study only if they died, declined future participation, or could not be located. Investigators, coordinators, and DRCR.net Coordinating Center staff were involved in locating participants who were lost to follow-up or unresponsive to scheduling attempts using telephone calls, certified letters, and a third-party search service to identify whether new contact information existed.

The main analysis consisted of a treatment group comparison of mean change in VA from baseline to 5 years, using analysis of covariance adjusting for baseline level and randomization stratification factors (laterality and baseline central subfield thickness [CST] on optical coherence tomography) with generalized estimating equations to account for the correlation between 2 study eyes of the same participant. All analyses were prespecified unless noted otherwise. The primary analysis followed intent-to-treat principle and included all randomized eyes. Multiple imputation using Markov chain Monte Carlo method was performed to impute missing visual acuities on the basis of treatment group assignment, laterality, all available VA data, and baseline CST. Outlying values were truncated to 3 SDs from the mean. Within-group means and percentages were calculated from observed data. Preplanned subgroup analyses were conducted by adding an interaction between subgroup and treatment. Visual field and CST data were imputed and analyzed similarly to VA outcomes. Secondary analyses and safety analyses were performed using binomial regression or Fisher exact test for binary outcomes, analysis of covariance for continuous outcomes, or marginal proportional hazards model for time-to-event outcomes. Z tests were performed to compare stratified model-based estimates when proportional hazards assumption failed. P values and 95% CIs were 2-sided. P less than .05 was considered statistically significant unless otherwise noted. For safety outcomes, a global P less than .01 from Fisher exact test performed including 3 groups (unilateral ranibizumab, unilateral prompt PRP, and bilateral) was considered statistically significant. All analyses used SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

The 5-year visit was completed for 240 study eyes (61%) in the ranibizumab and PRP groups (117 [69%] and 123 [65%] study eyes, excluding deaths, respectively) (Figure 1). The mean (SD) age was 52 (12) years, 135 (44%) were women, and 160 (52%) were white. Among participants who completed the 5-year visit (ie, completers), baseline characteristics appeared similar between treatment groups (eTable 1 in Supplement 3). However, eyes of completers had baseline VA approximately 5 letters (1 line) better than eyes of noncompleters, irrespective of treatment group. Among eyes of completers, 5 (5%) and 8 (7%) had high-risk PDR at the last visit compared with 7 (15%) and 5 (9%) among eyes of noncompleters in the ranibizumab and PRP groups, respectively. At the last completed visit, eyes of noncompleters in the ranibizumab (n = 74) and PRP (n = 80) groups had a mean (SD) change in VA of 3 (14) vs −4 (18) letters and CST of −56 (110) μm vs −8 (104) μm, respectively. Among the 240 completers, the median number of visits over 5 years was 43 in the unilateral ranibizumab group and 21 in the unilateral PRP group (eTable 1 in Supplement 3).

Figure 1. Completion of Follow-up.

aParticipants were not formally screened prior to obtaining informed consent.

bInformation was not collected on specific reasons for exclusion.

cParticipants with 2 eyes in the study had 1 eye randomly assigned to receive ranibizumab and 1 eye receive panretinal photocoagulation.

dTwo-year completed visits include those that occurred between 92 and 116 weeks.

eThree-year completed visits include those that occurred between 148 and 164 weeks.

fFour-year completed visits include those that occurred between 196 and 220 weeks.

gFive-year completed visits include those that occurred between 248 and 272 weeks.

PDR and DME Treatment

Ranibizumab Group

Among participants completing the 5-year visit, the mean (SD) number of injections for years 1 through 5 were 7.1 (2.2), 3.3 (2.9), 3.0 (2.8), 2.9 (2.7), and 2.9 (2.8), respectively (mean [SD] of 19.2 [10.9] cumulative injections over 5 years). A total of 2443 (98%) injections required by protocol for PDR treatment were administered. The number of eyes not receiving an injection within each year were 29 (25%), 32 (27%), 33 (28%), and 43 (37%) for years 2 through 5, respectively (eFigure 1 in Supplement 3). eTable 2 in Supplement 3 reports the number of injections for eyes with and without vision impairing central-involved DME at baseline. Focal/grid laser treatment was performed in 16 eyes (8%) through 5 years. Through 5 years, 26 eyes (14%) received PRP (2 eyes received PRP twice), 10 in the clinic and 18 with endolaser or an indirect laser delivery system during vitrectomy. Half of these 26 eyes initiated PRP after 2 years.

PRP Group

All eyes received PRP at baseline. Over 5 years, at least 1 additional PRP session was administered in 103 eyes (51%). Thirty-nine (38%) received the first supplemental PRP within 6 months of randomization; 25 (24%), 6 to 12 months; 28 (27%), 12 to 24 months; and 11 (11%), after 2 years. Among 92 eyes receiving additional PRP before 2 years, 20 (22%) also received at least 1 PRP session after 2 years. Among 5-year completers, 71 eyes (58%) received at least 1 study ranibizumab injection for DME through 5 years (43 at baseline and 28 during follow-up), for a mean (SD) cumulative total of 5.4 (7.9) injections over 5 years (eTable 2 in Supplement 3). Focal/grid laser treatment was performed in 26 eyes (13%) over 5 years.

Treatment Effect

Vision Outcomes

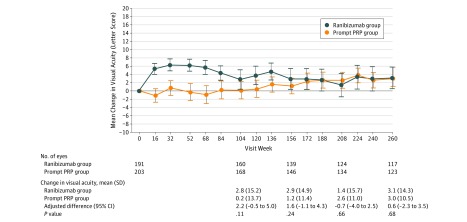

Visual acuity at the 5-year visit improved from baseline, with a mean (SD) of 3.1 (14.3) and 3.0 (10.5) letters in the ranibizumab and PRP groups, respectively (adjusted mean difference, 0.6 [95% CI, −2.3 to 3.5]; P = .68) (Table 1 and Figure 2), resulting in a mean VA (approximate Snellen equivalent) at 5 years of 20/25 in each group (compared with 20/32 at baseline). Results were similar when using alternative methods for handling missing data (eTable 3 in Supplement 3). Treatment group differences were not statistically significantly different for eyes either with or without DME at baseline (eTable 4 in Supplement 3). The mean (SD) change in VA area under the curve letter score over 5 years was 3.3 (9.5) in the ranibizumab group compared with 1.5 (7.5) in the PRP group (adjusted mean difference, 1.6 [95% CI, 0-3.2]; P = .05) (eFigure 2 in Supplement 3). Additional VA outcomes are shown in Table 1 and in eFigures 3, 4, 5, and 6 in Supplement 3. Exploration of 5 preplanned baseline subgroups (DME with decreased VA, DME regardless of VA, baseline VA, prior DME treatment history, and diabetic retinopathy severity) did not identify an interaction between any subgroups and treatment (eTable 5 in Supplement 3).

Table 1. Change in Visual Acuity (VA) at 5 Years.

| Variable | Ranibizumab Groupa | PRP Groupa | Adjusted Difference (95% CI)b | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 260-wk (5-y) Visit | ||||

| No. of eyes | 117 | 123 | NA | NA |

| VA Letter Score at Baseline | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 77 (12) | 78 (11) | NA | NA |

| Median (IQR) | 79 (75 to 85) | 80 (72 to 85) | NA | NA |

| Snellen equivalent, mean | 20/32 | 20/32 | NA | NA |

| VA Letter Score at 5 y | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 80 (16) | 81 (12) | NA | NA |

| Median (IQR) | 84 (78 to 89) | 84 (77 to 89) | NA | NA |

| Snellen equivalent, mean | 20/25 | 20/25 | NA | NA |

| Snellen equivalent, No. (%) | ||||

| ≥20/20 | 60 (51) | 66 (54) | NA | NA |

| 20/25 | 25 (21) | 18 (15) | NA | NA |

| 20/32 | 11 (9) | 15 (12) | NA | NA |

| 20/40 | 7 (6) | 9 (7) | NA | NA |

| 20/50 | 4 (3) | 5 (4) | NA | NA |

| 20/63 | 2 (2) | 3 (2) | NA | NA |

| 20/80 | 0 | 1 (<1) | NA | NA |

| 20/100 | 0 | 3 (2) | NA | NA |

| 20/125 | 0 | 1 (<1) | NA | NA |

| 20/160 | 2 (2) | 0 | NA | NA |

| ≤20/200 | 6 (5) | 2 (2) | NA | NA |

| Change in VA Letter Score at 5 y | ||||

| Mean (SD)c | 3.1 (14.3) | 3.0 (10.5) | 0.6 (−2.3 to 3.5) | .68d |

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (−2.0 to 10.0) | 3.0 (−3.0 to 8.0) | NA | NA |

| Letters improvement, No. (%)e | ||||

| ≥15 | 14 (26) | 13 (23) | 1 (−12 to 15) | .86 |

| ≥10 | 28 (52) | 23 (41) | 6 (−10 to 21) | .47 |

| Letters worsening, No. (%) | ||||

| ≥10 | 7 (6) | 11 (9) | −3 (−11 to 5) | .42 |

| ≥15 | 7 (6) | 7 (6) | −1 (−7 to 5) | .84 |

| Area Under the Curve for Change in VA Letter Score Over 5 y | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.3 (9.5) | 1.5 (7.5) | 1.6 (0 to 3.2) | .05 |

| Median (IQR) | 2.8 (−1.3 to 6.3) | 1.0 (−3.0 to 5.3) | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable; PRP, panretinal photocoagulation.

Observed data only, including participants who completed the 5-year visit.

Treatment group mean (SD) and median (IQR) are calculated from observed 5-year data. Differences (ranibizumab group minus PRP group), CIs, and 2-sided P values were obtained using of analysis of covariance for continuous outcomes and binomial regression for binary outcomes, with adjustment for baseline VA, laterality, baseline central subfield thickness, and correlation between 2 study eyes of the same participant, and multiple imputation for missing data unless otherwise specified. When binomial regression model failed to converge, covariates were removed from the model. Visual acuity change was truncated to 3 SD from the mean (−47 to 52) to minimize the effect of outliers (5 eyes for ranibizumab, all on the negative end). No imputation was performed for missing area under the curve for change in VA.

The mean (SD) change in VA letter score at 2 years among participants who completed the 5-year visit was 3.5 (14.6) vs 0.9 (12.1) for ranibizumab and PRP groups, respectively (eFigure 2 in Supplement 3).

P = .47 for comparing mean change in VA letter score at 5 years between treatment groups, with additional adjustment for potential baseline confounders, including age, duration of diabetes, hemoglobin A1c level, prior treatment for diabetic macular edema, and diabetic retinopathy severity on fundus photographs graded by the reading center.

Including 54 and 56 eyes in the ranibizumab and PRP groups, respectively, with baseline VA 20/32 or worse.

Figure 2. Mean Change in Visual Acuity From Baseline Over Time for the Overall Cohort.

Treatment group means are calculated from observed data for the overall cohort and are truncated to 3 SD from the mean to minimize the effect of outliers. Differences (ranibizumab group minus panretinal photocoagulation [PRP] group), CIs, and 2-sided P values were obtained by intention-to-treat analysis using of analysis of covariance, with adjustment for baseline visual acuity, laterality, baseline central subfield thickness, correlation between 2 study eyes of the same participant, and multiple imputation for missing data.

In an ancillary study, the mean (SD) change in cumulative visual field total point score from baseline, combining Humphrey visual field 30-2 and 60-4 test patterns, was −330 (645) dB vs −527 (635) dB in the ranibizumab (n = 41) and PRP (n = 38) groups, respectively (adjusted mean difference, 208 dB [95% CI, 9-408]; P = .04) (eTable 6 and eFigure 7 in Supplement 3) and a worsening between years 2 and 5 of 273 (539) dB and 97 (481) dB, respectively. No meaningful differences between groups in patient-centered outcomes as measured by the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire and the University of Alabama Birmingham Low Luminance Questionnaire were identified (eTable 7 in Supplement 3).

Diabetic Retinopathy, Macular Edema, and Related Conditions

At the 5-year visit, among eyes with baseline DME (n = 40), the mean (SD) CST decreased from baseline by 139 (157) μm and 59 (102) μm in the ranibizumab and PRP groups, respectively (adjusted mean difference, −31 [95% CI, −74 to 12]; P = .16); CST increased by 10% or more at 5 years in 2 (11%) and 4 eyes (18%), respectively. Eyes without baseline DME (n = 192) had a 22% vs 38% cumulative probability of developing vision-impairing DME by 5 years in the ranibizumab and PRP groups, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.4 [95% CI, 0.3-0.7]; P < .001) (eFigure 8 in Supplement 3); CST increased by 10% or more at 5 years in 5 (5%) and 14 (14%) eyes, respectively.

Among 90 eyes in the ranibizumab group that had gradable color fundus photographs at 5 years, 41 (46%) were improved from baseline by 2 or more steps in the Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale, including 30 (33%) with non-PDR, and 9 (10%) with complete resolution of diabetic retinopathy (Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study level 20 or better) on fundus photographs. Twenty-six of 90 eyes (29%) in the ranibizumab group and 28 of 93 eyes (30%) in the PRP group had NV visible on color photographs at 5 years (adjusted difference, −1% [95% CI, −14% to 12%]; P = .83), of which 4 and 7 eyes, respectively, had high-risk PDR.

Through 5 years, retinal detachment was identified on clinical examination in 12 and 30 eyes in the ranibizumab and PRP groups, respectively (cumulative probabilities, 7% vs 18%; hazard ratio, 0.4 [95% CI, 0.2-0.8]; P = .004) (eFigure 9 in Supplement 3), and 10 and 24 eyes, respectively, developed traction retinal detachments (Table 2). The retinal detachment involved the center of the macula in 2 and 9 eyes in the ranibizumab and PRP groups, respectively. Four eyes in the ranibizumab group and 11 in the PRP group received vitrectomy because of retinal detachment; no other procedures for retinal detachment were performed. Vitreous hemorrhage developed in 91 eyes in the ranibizumab group and 93 in the PRP group (cumulative probabilities, 58% vs 54%; adjusted difference, 4% [95% CI, −7% to 16%]; P = .47) (eFigure 10 in Supplement 3). Rates of neovascular glaucoma and iris NV were low in both groups (eFigures 11 and 12 in Supplement 3). Vitrectomy was performed in 21 and 39 eyes in the ranibizumab and PRP groups, respectively (cumulative probabilities, 15% vs 22%; hazard ratio, 0.5 [95% CI, 0.3-0.8]; P = .008); vitrectomy indications are listed in eTable 8 in Supplement 3.

Table 2. Change in Diabetic Retinopathy.

| Variable | No. (%) | Adjusted Difference, % (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ranibizumab Group | PRP Group | ||

| Diabetic Retinopathy on Fundus Photographs at 5 yb | |||

| No. of eyes | 90 | 93 | NA |

| Eyes without PDR (≤level 60) | 39 (43) | 34 (37) | NA |

| Eyes with regressed NV (level 61A) | 25 (28) | 31 (33) | NA |

| Eyes with active NV (≥level 61B) | 26 (29) | 28 (30) | NA |

| Eyes improving from PDR (≥level 61) to NPDR (≤level 53) | 30 (33) | NA | NA |

| Eyes without retinopathy (≤level 20) | 9 (10) | NA | NA |

| Eyes improving ≥2 steps in diabetic retinopathy severity on fundus photographs at 5 yc | 41 (46) | NA | NA |

| At Any Timed | |||

| No. of eyes | 191 | 203 | NA |

| Retinal detachment | |||

| Tractional retinal detachment | 10 (5) | 24 (12) | −7 (−12 to −2)e |

| Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment | 2 (1) | 1 (<1) | 1 (−1 to 2) |

| Unspecified retinal detachment | 3 (2) | 6 (3) | −1 (−4 to 2) |

| Any retinal detachment | 12 (6) | 30 (15) | −9 (−14 to −4)e |

| Retinal detachment that required for vitrectomy | 4 (2) | 11 (5) | −3 (−7 to 0) |

| Retinal detachment in the center of macula on clinical examination | 2 (1) | 9 (4) | −3 (−7 to 0) |

| Retinal detachment in the center of macula on clinical examination and VA ≤38 | 0 | 3 (1) | NA |

| Neovascular glaucoma | 6 (3) | 9 (4) | −2 (−6 to 2) |

| NV of the iris | 5 (3) | 3 (1) | 1 (−1 to 3)e |

| Vitreous hemorrhage | 91 (48) | 93 (46) | 2 (−6 to 11)e |

| Vitrectomy | 21 (11) | 39 (19) | −7 (−14 to −1)e |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; NPDR, nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy; NV, neovascularization; PDR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy; PRP, panretinal photocoagulation; VA, visual acuity.

No imputation was performed for missing data. Treatment group differences are estimated using binomial regression adjusting for the correlation between 2 study eyes of the same participant (unless otherwise specified).

Observed data only, including participants who had gradable fundus photograph at 5-year visit with baseline Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale level of 61B or worse (active neovascularization) as graded by the reading center.

Eyes graded by the reading center as receiving PRP (level 60) at follow-up are counted as not improving.

Adverse events were collected at any time during study follow-up.

Adjusted for baseline optical coherence tomography central subfield thickness and laterality and correlation between 2 study eyes of the same participant.

Injection-related endophthalmitis occurred in 1 of 4113 injections among 306 eyes receiving at least 1 injection (1 eye was in the ranibizumab group). Cataract extraction occurred in 31 (16%) and 38 eyes (19%) in the ranibizumab and PRP groups, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3. Systemic and Ocular Adverse Events of Interest Through 5 Years of Follow-up.

| Variable | No. (%) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants With 2 Study Eyes (1 in Each Group) | Ranibizumab Group | PRP Group | ||

| Systemic Adverse Eventsa,b | ||||

| No. of participants | 89 | 102 | 114c | NA |

| Vascular events defined by APTC criteria occurring at least once through 5 yd | ||||

| Nonfatal myocardial infarctione | 3 (3) | 6 (6) | 4 (4) | .64 |

| Nonfatal strokee | 3 (3) | 6 (6) | 7 (6) | .65 |

| Death due to potential vascular cause or unknown causef | 6 (7) | 7 (7) | 2 (2) | .13 |

| Any event | 12 (13) | 18 (18) | 12 (11) | .31 |

| Prespecified events occurring at least once through 5 y | ||||

| Death from any cause | 8 (9) | 13 (13) | 7 (6) | .24 |

| Hospitalization | 54 (61) | 66 (65) | 61 (54) | .24 |

| Serious adverse event | 56 (63) | 68 (67) | 63 (55) | .21 |

| Hypertension | 28 (31) | 38 (37) | 28 (25) | .13 |

| Ocular Adverse Eventsa,g | ||||

| No. of eyes | NA | 191 | 203 | NA |

| No. of injections | NA | 3132 | 981 | NA |

| Ocular adverse events occurring at least once through 5 y | ||||

| Endophthalmitis | NA | 1 (<1) | 0 | NA |

| Inflammationh | NA | 3 (2) | 10 (5) | .05 |

| Retinal tear | NA | 1 (<1) | 0 | NA |

| Cataract surgery | NA | 31 (16) | 38 (19) | .62 |

| Elevation in IOP (met any of the criteria)i | NA | 30 (16) | 36 (18) | .58 |

| Increase of IOP ≥10 mm Hg from baseline at any visit | NA | 17 (9) | 29 (14) | .10 |

| IOP ≥30 mm Hg at any visit | NA | 6 (3) | 11 (5) | .39 |

| Initiation of glaucoma medications at any visit | NA | 18 (9) | 21 (10) | .67 |

| Received glaucoma procedure at any visit | NA | 6 (3) | 4 (2) | .37 |

Abbreviations: APTC, Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration; IOP, intraocular pressure; NA, not applicable; PRP, panretinal photocoagulation.

Unless otherwise specified adverse events were collected at any time during study follow-up. Some events may have been reported more than once (ie, at multiple visits). Including participants/study eyes that experienced at least 1 adverse event of interest.

Systemic adverse events were classified as occurring in the unilateral PRP, unilateral ranibizumab, or bilateral treatment group, and Fisher exact test was performed to compare the 3 groups. If the overall test was significant (P < .01), pairwise between-group comparisons were performed, with P < .01 considered as evidence of a treatment group difference.

Among the 114 unilateral participants who were assigned to PRP group, 59 (52%) received at least 1 anti–vascular endothelial growth factor injection during follow-up.

Vascular events were defined according to the criteria of the APTC.

Defined as no death prior to outcome time point.

From any potential vascular or unknown cause.

P values are based on binomial regression adjusting for the correlation between 2 study eyes of the same participant.

Inflammation included the presence of inflammatory cells or flare in the anterior chamber, pseudohypopyon, chorioretinitis, choroiditis, pseudoendophthalmitis, iritis, uveitis, scleritis, and the presence of vitreal cells.

Elevated IOP was defined as an increase in IOP of 10 mm Hg or more from baseline at any visit, an IOP of 30 mm Hg or more at any visit, the initiation of medication to lower IOP that was not in use at baseline, or glaucoma surgery.

Systemic Adverse Events

Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration8 arteriothromboembolic events were reported in 12 of 89 participants (13%) with 2 study eyes; 18 of 102 participants (18%) and 12 of 114 participants (11%) with 1 study eye randomly assigned to ranibizumab or PRP, respectively (P = .31 using Fisher exact test including all 3 groups) (Table 3 and eFigure 13 in Supplement 3). No differences were identified with a P value less than .01 among these 3 groups for percentage of participants with serious adverse events, hospitalizations, deaths, or events in each MedDRA system organ class (except the system organ class Infections and Infestation, 39 [44%] in the bilateral group, 39 [38%] in the ranibizumab group, and 24 [21%] in the PRP group [P = .001]) (eTables 9 and 10 in Supplement 3).

Discussion

In this randomized clinical trial of intravitreous ranibizumab compared with PRP for treatment of individuals with PDR, VA at 5 years was good in both groups (approximate mean VA, 20/25), consistent with the 2-year data. No statistically significant differences were identified between the treatment groups in mean change in VA at 5 years or over 5 years. Patient-reported vision-related quality of life scores were similar between groups over 5 years, although more eyes in the PRP group developed vision-impairing DME compared with the ranibizumab group. More than half of the eyes in the PRP group received ranibizumab for DME treatment during the study. Results appeared similar irrespective of whether DME was present at baseline, suggesting PRP was not harmful to DME treatment in the presence of ranibizumab. These results should be considered in the context of only 60% of participants (66% excluding deaths) completing the 5-year visit.

Considering that PRP has been an effective treatment for PDR for more than 45 years, an important question for this trial was whether eyes in the ranibizumab group develop serious complications in the absence of PRP over 5 years. Overall, for participants completing the 5-year visit, few eyes in either group developed neovascular glaucoma or iris NV and the rates were similar between groups. Although the overall rate of retinal detachments, most of which were traction retinal detachments, was higher in the PRP group (15%) compared with the ranibizumab group (6%), most detachments did not progress to involve the center of the macula (4% vs 1%, respectively) and most of these eyes did not undergo vitrectomy (5% vs 2%, respectively), suggesting most tractional retinal detachments were not vision-threatening. Few eyes in either group had substantial VA loss (≥15 letters compared with baseline) at the 5-year visit (6% in both groups). As anticipated, the PRP group, on average, had more peripheral visual field loss from baseline through 2 years than the ranibizumab group. However, visual field loss, on average, progressed in both the PRP and ranibizumab groups from years 2 through 5, and the difference between groups diminished in this small substudy. The degree of this decline was unanticipated in the ranibizumab group. Further analysis of visual field seems warranted.

Almost half of the eyes in both groups developed any vitreous hemorrhage over 5 years, with 41% of the eyes in the PRP group with vitreous hemorrhage undergoing vitrectomy compared with 22% in the ranibizumab group. The decision to perform vitrectomy was made by an unmasked investigator, which could have biased the decision to proceed to vitrectomy in the PRP group. Also, eyes in the ranibizumab group with vitreous hemorrhage could receive ranibizumab to treat NV, whereas no anti-VEGF treatment was provided to eyes in the PRP group unless they had coexistent DME, leaving vitrectomy as the treatment option.

An additional important long-term consideration was whether eyes in the ranibizumab group would receive a decreasing frequency of injections while still maintaining VA during the study. During the first year, eyes in the ranibizumab group received a mean of 7 injections for either NV or DME. Each year thereafter, eyes in the ranibizumab group received an average of 3 injections. Although the overall number of injections was reduced from year 1, approximately 75% of eyes in the ranibizumab group still received at least 1 injection each year through 4 years, with 63% receiving at least 1 injection in year 5. With this reduction in treatment, mean VA change from baseline remained fairly constant between years 2 and 5. Additionally, rates of diabetic retinopathy improvement were maintained with 46% of the participants in the ranibizumab group showing reduction of 2 or more steps in Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale at 5 years.

Prior ocular studies on systemic safety of anti-VEGF with intravitreous anti-VEGF have reported inconsistent results. An interim 4-year data analysis from Protocol S suggested a potential increased risk for Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration events with ranibizumab (P = .10); however, rates of such events with ranibizumab were within the range of variability seen across studies.9 Furthermore, the 5-year data from Protocol S does not show statistically significant differences in Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration events between the treatment groups. The endophthalmitis rate was low, occurring in 0.02% of injections or 0.3% of eyes; no other ocular safety concerns were identified.

Limitations

Despite considerable efforts to retain participants, less than 65% of each group was followed up through 5 years. Thus, interpretation of the long-term results of this study must be made with caution. Retention rates were similar between the treatment groups. No evidence of major differences in most observable baseline factors between treatment groups for the completers or noncompleters were found, although completers, on average, had baseline VA of approximately 1 line better. Eyes of noncompleters in the ranibizumab group had more improvement in VA and optical coherence tomography CST at the last measured follow-up visit than eyes in the PRP group of noncompleters. However, based on the course of completers, greater improvement might be expected with longer follow-up of the noncompleters in the PRP group compared with the ranibizumab group. Although different methods for handling missing data produced similar results, outcomes for noncompleters are unknown, including risk of serious recurrent NV, hemorrhage, or traction retinal detachment, and potential biases cannot be quantified.

Conclusions

Although loss to follow-up was relatively high in this cohort, VA in most study eyes that completed follow-up was very good over 5 years. Severe vision loss or serious complications of PDR, such as neovascular glaucoma, iris NV, or macular traction retinal detachments, were uncommon with PRP or ranibizumab. Ranibizumab resulted in lower rates of development of vision-impairing DME and less visual field loss. There were no meaningful treatment group differences in patient-centered outcomes. Individual patient factors, such as anticipated potential for maintaining scheduled visits, number of visits, cost, and systemic health, should be considered when choosing a treatment for PDR. These findings support either ranibizumab or PRP as viable treatments for PDR.

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics by Treatment and 5-Year Visit Completion Status

eTable 2. Treatment for Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy and Diabetic Macular Edema

eTable 3. Treatment-group Comparison of Mean Change in Visual Acuity at 5 Years: Sensitivity Analysis

eTable 4. Change in Visual Acuity at 5 Years Stratified by Baseline DME Status

eTable 5. Change in Visual Acuity at 5 Years: Pre-planned Subgroup Analysis

eTable 6. Change in Visual Field Testing Data at 5 Years

eTable 7. Patient-centered Outcomes at 5 Years

eTable 8. Indications for Vitrectomy

eTable 9. Adverse Events Through 5 Years by System Organ Class

eTable 10. Infections and Infestations Events Through 5 Years

eFigure 1. Intravitreous Injection by Year (Ranibizumab Group Only)

eFigure 2. Mean Changes in Visual Acuity From Baseline Over Time for 5-Year Completers Only

eFigure 3. Changes in Visual Acuity From Baseline Over Time: ≥15 Letter Score Improvement (includes only eyes with baseline visual acuity 20/32 or worse)

eFigure 4. Changes in Visual Acuity From Baseline Over Time: ≥10 Letter Score Improvement (includes only eyes with baseline visual acuity 20/32 or worse)

eFigure 5. Changes in Visual Acuity From Baseline Over Time: ≥10 Letter Score Worsening for the Overall Cohort

eFigure 6. Changes in Visual Acuity From Baseline Over Time: ≥15 Letter Score Worsening for the Overall Cohort

eFigure 7. Changes in Cumulative Visual Field Total Point Score for the Overall Cohort

eFigure 8. Kaplan-Meier Plot for Development of Vision-Impairing DME Among Eyes Without Vision-Impairing DME at Baseline

eFigure 9. Kaplan-Meier Plot for Eyes with Retinal Detachment

eFigure 10. Kaplan-Meier Plot for Eyes with Vitreous Hemorrhage

eFigure 11. Kaplan-Meier Plot for Eyes with Neovascular Glaucoma

eFigure 12. Kaplan-Meier Plot for Eyes with Neovascularization of the Iris

eFigure 13. Kaplan-Meier Plot for Time to First Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration Arteriothromboembolic Event

References

- 1.National diabetes fact sheet, 2007. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/5613/cdc_5613_DS1.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2018.

- 2.The Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group Photocoagulation treatment of proliferative diabetic retinopathy: Clinical application of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (DRS) findings, DRS report number 8. Ophthalmology. 1981;88(7):583-600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sivaprasad S, Prevost AT, Vasconcelos JC, et al. ; CLARITY Study Group . Clinical efficacy of intravitreal aflibercept versus panretinal photocoagulation for best corrected visual acuity in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy at 52 weeks (CLARITY): a multicentre, single-blinded, randomised, controlled, phase 2b, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10085):2193-2203. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31193-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gross JG, Glassman AR, Jampol LM, et al. ; Writing Committee for the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Panretinal photocoagulation vs intravitreous ranibizumab for proliferative diabetic retinopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(20):2137-2146. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gross JG, Glassman AR. A novel treatment for proliferative diabetic retinopathy: anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(1):13-14. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.5079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network (DRCRnet) public web site. http://drcrnet.jaeb.org/ViewPage.aspx?PageName=Home. Accessed July 10, 2018.

- 7.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration Collaborative overview of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy--I: prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke by prolonged antiplatelet therapy in various categories of patients: Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration. BMJ. 1994;308(6921):81-106. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6921.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gross JG, Glassman AR, Klein MJ, et al. Interim safety data comparing ranibizumab with panretinal photocoagulation among participants with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(6):672-673. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.0969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics by Treatment and 5-Year Visit Completion Status

eTable 2. Treatment for Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy and Diabetic Macular Edema

eTable 3. Treatment-group Comparison of Mean Change in Visual Acuity at 5 Years: Sensitivity Analysis

eTable 4. Change in Visual Acuity at 5 Years Stratified by Baseline DME Status

eTable 5. Change in Visual Acuity at 5 Years: Pre-planned Subgroup Analysis

eTable 6. Change in Visual Field Testing Data at 5 Years

eTable 7. Patient-centered Outcomes at 5 Years

eTable 8. Indications for Vitrectomy

eTable 9. Adverse Events Through 5 Years by System Organ Class

eTable 10. Infections and Infestations Events Through 5 Years

eFigure 1. Intravitreous Injection by Year (Ranibizumab Group Only)

eFigure 2. Mean Changes in Visual Acuity From Baseline Over Time for 5-Year Completers Only

eFigure 3. Changes in Visual Acuity From Baseline Over Time: ≥15 Letter Score Improvement (includes only eyes with baseline visual acuity 20/32 or worse)

eFigure 4. Changes in Visual Acuity From Baseline Over Time: ≥10 Letter Score Improvement (includes only eyes with baseline visual acuity 20/32 or worse)

eFigure 5. Changes in Visual Acuity From Baseline Over Time: ≥10 Letter Score Worsening for the Overall Cohort

eFigure 6. Changes in Visual Acuity From Baseline Over Time: ≥15 Letter Score Worsening for the Overall Cohort

eFigure 7. Changes in Cumulative Visual Field Total Point Score for the Overall Cohort

eFigure 8. Kaplan-Meier Plot for Development of Vision-Impairing DME Among Eyes Without Vision-Impairing DME at Baseline

eFigure 9. Kaplan-Meier Plot for Eyes with Retinal Detachment

eFigure 10. Kaplan-Meier Plot for Eyes with Vitreous Hemorrhage

eFigure 11. Kaplan-Meier Plot for Eyes with Neovascular Glaucoma

eFigure 12. Kaplan-Meier Plot for Eyes with Neovascularization of the Iris

eFigure 13. Kaplan-Meier Plot for Time to First Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration Arteriothromboembolic Event