Abstract

This Research Letter evaluates the amount of sugars found in cigarillos by brand.

In 2009, the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act banned characterizing flavors (primary recognizable flavors such as grape and vanilla), except menthol, in cigarettes. Flavors have been linked to higher tobacco initiation by youths.1 However, the legislation did not extend to other tobacco products such as cigarillos, which are thin, small cigars rolled in tobacco-based wrappers. Cigarillos are popular among youths and part of their appeal is the availability of various flavors.2 The flavor experience from tobacco products arises from the sensory integration of both smell and taste, the latter requiring dissolution and transport in saliva to receptors in the oral cavity. High-intensity sweeteners, routinely added in high amounts to smokeless tobacco products, exclusively activate the taste system.3,4 Many cigarillos are labeled as having a “sweet” flavor, and the perception of sweetness may also contribute to their appeal. This study determined levels of high-intensity sweeteners in wrappers and mouth-tips of cigarillos, where they would contact saliva, creating sweet taste.

Methods

Market sales data were used to identify the highest-selling US cigarillo flavors of 2016,5 which were categorized as (1) classic (such as original), (2) sweet, or (3) with characterizing flavor (such as grape or wine). For the purposes of the study, we purchased in July 2017 at least 1 cigarillo per flavor category from the 6 top selling US brands of 20165 and one brand popular with local youths.6

The tobacco filler was removed, the wrappers were cut into 2 unequal pieces (one-third the distance from the mouth-side), and the separate pieces (mouth-side, burn-side) and mouth tip (if present) were extracted using deionized water in duplicate. Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry4 was used to identify and quantify 12 sweeteners in the extracts (Figure 1). Relative sweetness was calculated by multiplying measured sweetener content by its sweetness factor (Figure 1), divided by the wrapper area, to yield (milligrams of sugar equivalents)/cm2 and compared with previously reported values for sugar-free candy, gum, and smokeless tobacco products.4 Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 7.01 for a 1-way analysis of variance with 3 Bonferroni posttests; P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

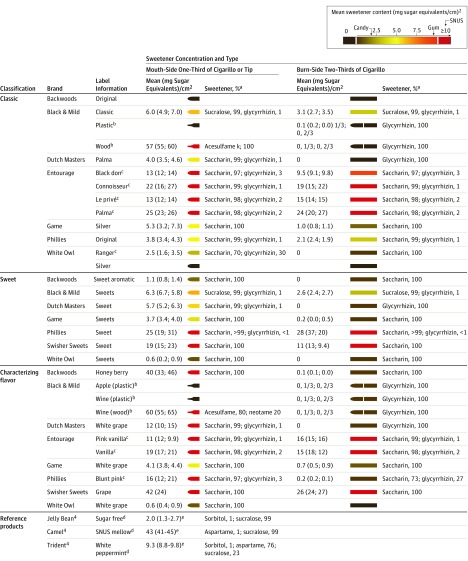

Figure 1. Brand, Label Information, and Mean Sweetness of Cigarillo Sections Categorized Into Classic, Sweet, and With Characterizing Flavor.

aSweeteners detected (sweetness factor vs table sugar): acesulfame K (200×), glycyrrhizin (50×), neotame (8000×), saccharin (400×), sucralose (600×). Sweeteners not detected in wrappers: aspartame (200×), sorbitol (0.55×); advantame (20 000×), glucose (0.7×), sodium cyclamate (30×), stevioside (300×), sucrose (1×). Spectra available4 except for glycyrrhizin (m/z 821 [M−H]−), neotame (m/z 380 [M+H]+), and advantame (m/z 458 [M−H]−).

bTip was extracted separately from the wrapper and both parts were tested.

cSlightly larger than other tested cigarillos, which were 103 to 112 mm long and 10 to 11 mm in diameter. Entourage was 135 mm long and 10 mm in diameter; White Owl Ranger, 160 mm and 12 mm; Phillies Blunt pink, 125 mm and 16 mm.

dCalculated as the sweetness content of the outer layer of the product corresponding to the average wrapper thickness (0.2 mm), divided by the surface area of that layer, to yield (mg sugar equivalents)/cm2.4

eValues reported as mean (95% CI).

Results

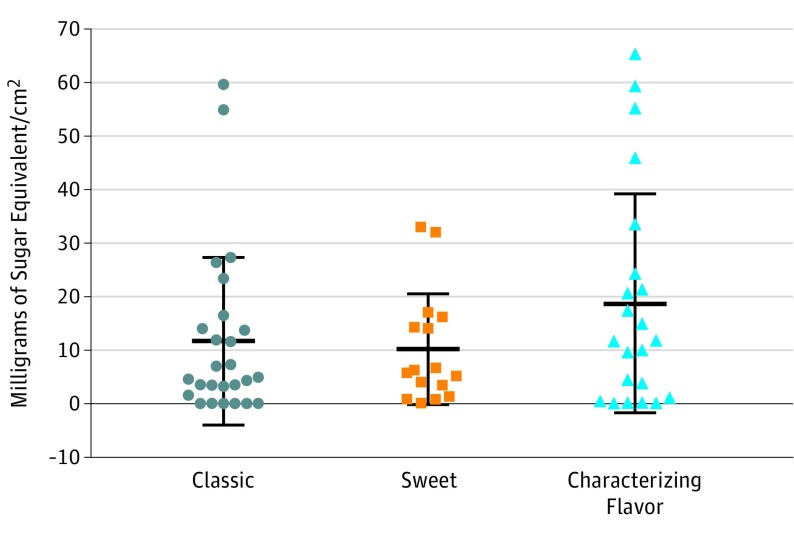

Thirty-one cigarillos (13 classic; 7 sweet; 11 with characterizing flavor; including 3 plastic-tipped and 2 wooden-tipped) were tested. Twenty-nine of these contained high-intensity sweeteners on the segment with saliva contact. The most prevalent sweeteners were saccharin in 22 and glycyrrhizin in 20 of the 31 cigarillos (Figure 1). Estimated sweetness intensities of cigarillo parts touching the mouth (mouth-side or tip) did not differ significantly among the classic type, which was 11.65 mg sugar-equivalents/cm2; sweet, 10.09 sugar-equivalents/cm2; and characterizing flavor, 18.62 sugar-equivalents/cm2 (P = .22; Bonferroni posttests: classic vs sweet, P > .99; classic vs characterizing flavor, P = .45; sweet vs characterizing flavor, P = .37; Figure 2). For 17 cigarillos, the sweetener was found mainly on the segment with saliva contact, but for 9 cigarillos the sweetener was distributed throughout the wrapper (Figure 1). Acesulfame K and neotame were only detected on the tips of the 2 wooden-tipped cigarillos (1 classic, 1 characterizing flavor), resulting in the highest sweetness rating for these 2 compared with all other cigarillos and reference products. In contrast, no sweetener was found on the tips of plastic-tipped cigarillos. Cigarillo segments with saliva contact were 74%, 45%, and 6% sweeter than the reference products, sugar-free candy (2.0 mg sugar-equivalents/cm2); gum (9.3 mg sugar-equivalents/cm2); and smokeless tobacco (43 mg sugar-equivalents/cm2) products, respectively (Figure 1).4

Figure 2. Statistical Comparison of Cigarillo Sections With Saliva Contact per Flavor Category.

The mean (SD) of measured sweetness ([mg sugar equivalents]/cm2)of cigarillo sections with saliva contact (mouth-side one-third or the tip) are shown for the 3 cigarillo flavor categories: classic, 11.65 (15.75); sweet, 10.09 (10.4); and characterizing flavor, 18.62 (20.6). No statistically relevant differences were found among the means (1-way analysis of variance, P = .22) or among Bonferroni multicomparison posttests (classic vs sweet, P > .99; classic vs characterizing flavor, P = .45; sweet vs characterizing flavor, P = .37).

Discussion

High-intensity sweeteners were commonly applied to the wrappers and wooden mouth-tips of cigarillos, whether labeled as classic, sweet, or characterizing flavor, at levels comparable with a smokeless tobacco product and a sugar-free candy and gum. Study limitations include possible underestimation of sweetener content by incomplete extraction, and nondetection of high molecular-weight sweeteners. Furthermore, the licorice-derived sweetener glycyrrhizin is a known additive to tobacco and may have migrated to the wrapper.

The placement of sweeteners on the mouth-side creates a sweet, pleasant taste and may reduce the aversive effects of smoking. As the US Food and Drug Administration considers expanding existing regulations on flavors to cigarillos, and state and local governments such as San Francisco implement flavored tobacco product bans, the definition of “characterizing flavor” should be expanded to include high-intensity sweeteners.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kong G, Bold KW, Simon P, Camenga DR, Cavallo DA, Krishnan-Sarin S. Reasons for cigarillo initiation and cigarillo manipulation methods among adolescents. Tob Regul Sci. 2017;3(2)(suppl 1):S48-S58. doi: 10.18001/TRS.3.2(Suppl1).6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosbrook K, Erythropel HC, DeWinter TM, et al. The effect of sucralose on flavor sweetness in electronic cigarettes varies between delivery devices. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0185334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miao S, Beach ES, Sommer TJ, Zimmerman JB, Jordt S-E. High-intensity sweeteners in alternative tobacco products. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(11):2169-2173. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giovenco DP, Spillane TE, Mauro CM, Martins SS. Cigarillo sales in legalized marijuana markets in the US. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;185:347-350. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kong G, Cavallo DA, Goldberg A, LaVallee H, Krishnan-Sarin S. Blunt use among adolescents and young adults: Informing cigar regulations. Tob Regul Sci. 2018;4(5):50-60. doi: 10.18001/TRS.4.5.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]