Key Points

Question

Are there factors that may mediate the higher incidence of hypertension among black adults compared with white adults?

Findings

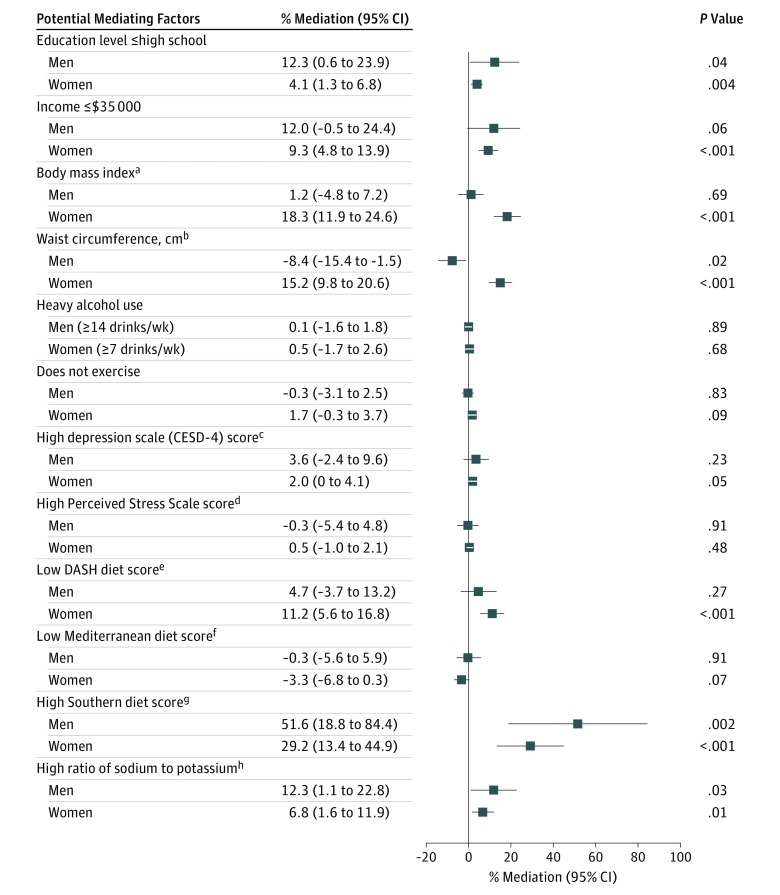

In this mediation analysis that included 6897 adults who participated in a follow-up visit 9.4 years (median) later, the largest statistical mediator of the difference in hypertension incidence between black and white participants was the Southern dietary pattern, accounting for 51.6% of the excess risk among black men and 29.2% of the excess risk among black women.

Meaning

These findings may provide insights into the sources of racial disparities in hypertension incidence.

Abstract

Importance

The high prevalence of hypertension among the US black population is a major contributor to disparities in life expectancy; however, the causes for higher incidence of hypertension among black adults are unknown.

Objective

To evaluate potential factors associated with higher risk of incident hypertension among black adults.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Prospective cohort study of black and white adults selected from a longitudinal cohort study of 30 239 participants as not having hypertension at baseline (2003-2007) and participating in a follow-up visit 9.4 years (median) later.

Exposures

There were 12 clinical and social factors, including score for the Southern diet (range, −4.5 to 8.2; higher values reflect higher level of adherence to the dietary pattern), including higher fried and related food intake.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Incident hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg, or use of antihypertensive medications) at the follow-up visit.

Results

Of 6897 participants (mean [SD] age, 62 [8] years; 26% were black adults; and 55% were women), 46% of black participants and 33% of white participants developed hypertension. Black men had an adjusted mean Southern diet score of 0.81 (95% CI, 0.72 to 0.90); white men, −0.26 (95% CI, −0.31 to −0.21); black women, 0.27 (95% CI, 0.20 to 0.33); and white women, −0.57 (95% CI, −0.61 to −0.54). The Southern diet score was significantly associated with incident hypertension for men (odds ratio [OR], 1.16 per 1 SD [95% CI, 1.06 to 1.27]; incidence of 32.4% at the 25th percentile and 36.1% at the 75th percentile; difference, 3.7% [95% CI, 1.4% to 6.2%]) and women (OR, 1.17 per 1 SD [95% CI, 1.08 to 1.28]; incidence of 31.0% at the 25th percentile and 34.8% at the 75th percentile; difference, 3.8% [95% CI, 1.5% to 5.8%]). The Southern dietary pattern was the largest mediating factor for differences in the incidence of hypertension, accounting for 51.6% (95% CI, 18.8% to 84.4%) of the excess risk among black men and 29.2% (95% CI, 13.4% to 44.9%) of the excess risk among black women. Among black men, a higher dietary ratio of sodium to potassium and an education level of high school graduate or less each mediated 12.3% of the excess risk of incident hypertension. Among black women, higher body mass index mediated 18.3% of the excess risk; a larger waist, 15.2%; less adherence to the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension diet, 11.2%; income level of $35 000 or less, 9.3%; higher dietary ratio of sodium to potassium, 6.8%; and an education level of high school graduate or less, 4.1%.

Conclusions and Relevance

In a mediation analysis comparing incident hypertension among black adults vs white adults in the United States, key factors statistically mediating the racial difference for both men and women included Southern diet score, dietary ratio of sodium to potassium, and education level. Among women, waist circumference and body mass index also were key factors.

This cohort study of black and white adults investigates demographic, physical, and lifestyle factors that might account for differences in incidence of hypertension in black vs white US adults.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease, including stroke, is the largest contributor to the mortality difference between the black and white populations in the United States, accounting for 34% of the difference in years of life lost in data from the National Health Interview Survey between 1986 to 1994; hypertension was the single largest contributor, accounting for 15% of the disparity.1

Even among individuals aged 8 to 17 years, data from the 1999-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey showed a higher prevalence of hypertension among black children than white children.2 The higher risk of developing hypertension among black adults persists to an age older than 75 years, with a higher incidence of hypertension from 2000 to 2007 among older black adults in both the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis,3 and from 2003 to 2016 in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) cohort.4

The reasons for the difference in the incidence and prevalence of hypertension between the black and white populations remain unknown,5 and a better understanding of these reasons could guide efforts to prevent hypertension and reduce the difference in mortality between the black and white populations. Mediation analysis of a US national cohort of black and white participants was used to identify factors associated with the higher incidence of hypertension among black participants.

Methods

REGARDS is a longitudinal cohort study of 30 239 black and white participants aged 45 years or older who were recruited between 2003 and 2007. With the goal of understanding racial differences in incident hypertension, inclusion in the current study was limited to the subset of participants with normal blood pressure levels at baseline and with hypertension status available at follow-up. Study eligibility included self-reported black or white race (by selection from categories used by the US Census), with exclusion of individuals reporting being either Hispanic or Latino.

At baseline, the cardiovascular disease risk profile of participants was assessed via a telephone interview and via an in-person examination that included blood pressure measurement, venipuncture, measures of adiposity (height, weight, and waist circumference), and electrocardiography. A similar assessment was performed at a follow-up visit that occurred a median of 9.4 years later between 2013 and 2016. Details of the study methods are provided elsewhere.4,6 All participants provided written informed consent and the study was approved by all participating institutional review boards.

At both the baseline and follow-up visits, blood pressure was assessed as the mean of 2 measures taken after the participant had been seated for 5 minutes. Participants without hypertension (systolic blood pressure <140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg, and self-report of not taking antihypertensive medications) at baseline were included in the analysis. Among those with normal blood pressure levels at baseline, incident hypertension was defined similarly at the second assessment.

Potential Mediating Factors

The selected potential mediating factors had either evidence of a racial difference in the prevalence, level of the risk factor, or evidence of an association with hypertension (with a suggestion of a racial difference in the prevalence or level). Mediation analysis7 was performed separately for men and women to assess the association of the 12 potential mediating factors (1 at a time) with the racial difference in the development of hypertension (a description of each potential mediating factor appears in Table 1).

Table 1. Description of Potential Mediating Factors Measured at Baseline.

| Potential Mediating Factor | Reporting Source | Classificationa |

|---|---|---|

| Education level ≤high school | No. of grades completed reported to the interviewer | Dichotomized as high school graduate or less vs some college or more |

| Income ≤$35 000 | Family income reported by selected categories to the interviewer | Dichotomized as ≤$35 000 vs >$35 000 |

| Body mass indexb | Height and weight measured at in home visit | Continuous variable with range from 11.5 to 59.9; higher scores are associated with greater adiposity |

| Waist circumference | Measured at home using a tape measure positioned midway between the lowest rib and the iliac crest with the participant standing | Continuous variable with range from 48.3 to 183.5 cm; higher scores represent larger waist circumference |

| Heavy alcohol use | NIAAA classification based on self-reported No. of drinks per wk to the interviewer | Dichotomized as having vs not having ≥7 drinks/wk for women and ≥14 drinks/wk for men |

| Does not exercise | No. of times per wk of exercise enough to sweat reported to the interviewer | Dichotomized as none vs some |

| High depression scale score | Interviewer-administered CESD-48 | Continuous variable with range from 0 to 12; higher scores represent more depressive symptoms |

| High Perceived Stress Scale score | Interviewer-administered Perceived Stress Scale9 | Continuous variable with range from 0 to 16; higher scores reflect more perceived stress |

| Low DASH diet score10 | Assessed using data from the self-administered Block Food Frequency questionnaire11 | Continuous variable (original score subtracted from 38) with range from 0 to 29; higher scores reflect being less compliant with the DASH diet |

| Low Mediterranean diet score12 | Assessed using data from the self-administered Block Food Frequency questionnaire11 | Continuous variable (original score subtracted from 9) with range from 0 to 9; higher scores reflect being less compliant with the Mediterranean diet |

| High Southern diet score13 | Assessed using data from the self-administered Block Food Frequency questionnaire11 | Continuous variable with range from −4.5 to 8.2; higher scores represent greater compliance with the Southern diet |

| High ratio of sodium to potassium | Calculated from food nutrient mapping using data from the self-administered Block Food Frequency questionnaire11 | Continuous variable with range from 0.3 to 2.5; higher scores represent a greater intake of sodium relative to potassium |

Abbreviations: CESD-4, 4-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension; NIAAA, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

All mediating factors have been defined or rescaled so that higher values are presumed to be associated with a higher risk of hypertension.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

An exploratory mediation analysis also was performed for an additional 9 factors assessed only at the follow-up visit. To increase comparability between the potential mediating factors, some variables were “inverted” so higher values for all variables are hypothesized to be inversely associated with the risk of incident hypertension. Similarly, dichotomous factors were defined so the presence of the factor was associated with higher hypothesized risk of incident hypertension (such as income ≤$35 000).

Analysis

Mediation analysis provides an approach to estimate the proportion of an association (in this study, the association of race with incident hypertension) that is attributable to potential mediating factors (in this study, the 12 potential mediating factors). This approach estimates what proportion of the association between race and incident hypertension might be attributable to racial differences in potential mediating factors (an indirect effect), with the remaining proportion as the direct association of race.

This study focused on the identification of factors that mediate the association of race with incident hypertension by (1) having a differential prevalence or level in black and white participants and (2) being associated with the incidence of hypertension. The analysis was implemented using the difference in coefficients,14 in which the change in the logistic regression β coefficient associated with race (adjusted for the covariates of age and baseline systolic blood pressure) was assessed with subsequent adjustment for potential mediating factors. The analysis was performed in 3 stages.

Stage 1: Assessment of Racial Differences in the Prevalence of Each Potential Mediating Factor

The association of race with each risk factor was assessed by first calculating the age-adjusted least-squares estimate of the mean risk factor level by race. Dichotomous factors were coded as 0 or 1, so the mean for these variables is equivalent to the proportion with the trait. The least-squares means (and 95% CIs) are reported for both white and black participants along with the difference between these mean scores (and 95% CIs) to assess the racial differences.

Stage 2: Assessment of the Association of Potential Mediating Factors With Incident Hypertension

The association of mediating factors with incident hypertension was assessed by calculating the odds ratios (ORs) and using logistic regression to adjust for age group (45-54, 55-64, 65-74, and ≥75 years) and baseline systolic blood pressure level. To facilitate the interpretation of the magnitude of associations between the mediating factors, the ORs were provided for presence vs absence of the dichotomous factors and for a standard deviation difference in the continuous factors.

For dichotomous factors, the proportion of the population with incident hypertension for those with vs without the factor was calculated from the same logistic model and the absolute difference was calculated as the difference in these proportions. The 95% CIs for both the proportion and the difference was calculated using bootstrap methods with 1000 replications.

For continuous factors, a similar approach was used to calculate the proportion with incident hypertension for those at the 25th and 75th percentile of the distribution, and the absolute difference in these proportions for this interquartile range (again with bootstrap estimates for the 95% CIs).

Stage 3: Assessment of the Magnitude of the Mediation of the Difference Between Black and White Participants in Risk of Incident Hypertension by Each of the Potential Mediating Factors

The magnitude of the mediation of the racial difference in the risk of developing hypertension was assessed as the difference in the β coefficient for race in 2 logistic models predicting incident hypertension after (1) adjusting for age group and baseline systolic blood pressure and (2) further adjusting for each of the potential mediating factors individually. The 95% CIs for the difference in the race β coefficient between the 2 models were calculated using bootstrap methods with 1000 replications.

Additional Details About the Analyses

It is also possible for the association of race and incident hypertension to be mediated if a factor has a differential strength of association among black and white participants (ie, race × potential mediating factor interaction); however, this mechanism for mediation was beyond the scope of this study.

Because the racial difference in the level of a particular risk factor may not be consistent among men and women, the analyses were stratified by sex. For example, black women have a higher body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) than white women; however, there is a much smaller racial difference among men.

Approximately 16% of the cohort died and an additional 24% withdrew from the study during the follow-up period, opening the possibility of attrition bias affecting the study results. To assess the potential magnitude of attrition bias, the analyses were repeated using inverse probability weighting.15 The inverse probability weighting approach models the lost participants by assigning heavier weights to observed individuals who are similar to those who die or withdraw.

Because the goal of the study was to understand the higher prevalence of mediating factors among survivors, analyses of the individuals retained in the study may be more informative; however, the inverse probability weighting findings also are included. Post hoc analyses also were performed stratifying on baseline age of younger or older than 60 years to assess age as an effect modifier of the difference between black and white participants in the incidence of hypertension.

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) and significance was defined by a 2-sided α = .05.

Results

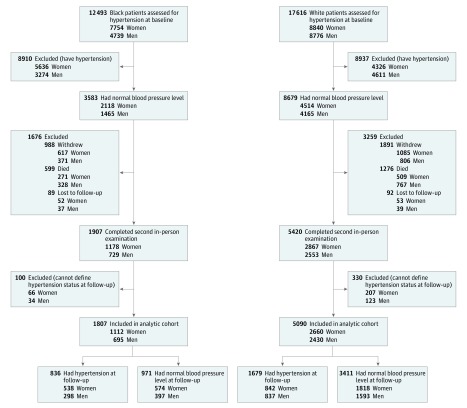

The flow of the participants from inclusion in the baseline cohort (12 262 participants with normal blood pressure levels) to inclusion in the analytic cohort (6897 who participated in the second examination; mean [SD] age, 62 [8] years; 26% were black adults; and 55% were women) appears in Figure 1. The individuals who were excluded for death or study withdrawal were older compared with those included in the analysis (mean [SD] age of 64.4 [8.4] vs 61.7 [10.6] years, respectively) and more likely male (47% vs 45%), black (33% vs 26%), to have incomes of $35 000 or below (42% vs 29%), and an education level of high school graduate or less (40% vs 26%).

Figure 1. Flow of Participants From Baseline to the Analytic Cohort and Hypertensive Status at the Follow-up Visit.

There were 130 participants excluded due to data anomalies. More than half of the study participants had hypertension at baseline and were excluded from the analysis. During the approximate 10-year follow-up, approximately 24% of the participants withdrew from the study (reflecting a 97.1% annual retention rate) and 13% to 14% died. Of those completing the second in-person examination, hypertension status could be assessed in approximately 95% of participants.

The characteristics of the participants included in the analysis appear in Table 2. Black participants were younger (approximately 60 vs 63 years), had an education level of high school graduate or less, had an income level of $35 000 or less, and had a higher prevalence of most factors potentially associated with incident hypertension compared with white participants.

Table 2. Participant Characteristics by Sex and Race.

| Potential Mediating Factor | Men | Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (n = 2430) | Black (n = 695) | White (n = 2660) | Black (n = 1112) | |

| Age, mean (SD) [range], y | 62.9 (8.3) [45 to 88] | 60.9 (8.2) [45 to 83] | 62.9 (8.3) [45 to 88] | 60.6 (8.4) [45 to 87] |

| Education level ≤high school, No. (%) | 467 (19.2) | 257 (37.0) | 683 (25.7) | 373 (33.5) |

| Income ≤$35 000, No./total No. (%) | 460/2234 (20.6) | 245/637 (38.5) | 790/2275 (34.7) | 471/993 (47.4) |

| Body mass indexa | ||||

| Total No. | 2426 | 693 | 2656 | 1106 |

| Mean (SD) | 27.5 (4.2) | 27.9 (5.0) | 26.9 (5.4) | 30.3 (6.2) |

| Waist circumference, cmb | ||||

| Total No. | 2427 | 694 | 2641 | 1105 |

| Mean (SD) | 97.2 (11.4) | 96.0 (13.3) | 85.1 (14.0) | 91.9 (14.4) |

| Heavy alcohol use, No./total No. (%)c | 109/2398 (4.5) | 26/677 (3.8) | 141/2631 (5.4) | 24/1088 (2.2) |

| Does not exercise, No./total No. (%) | 493/2405 (20.5) | 171/687 (24.9) | 757/2621 (28.9) | 369/1100 (33.5) |

| Depression scale (CESD-4) scored | ||||

| Total No. | 2410 | 689 | 2644 | 1097 |

| Median (IQR) | 0 (0 to 0) | 0 (0 to 1.0) | 0 (0 to 1.0) | 0 (0 to 2.0) |

| Perceived Stress Scale score, median (IQR)e | 2.0 (0 to 4.0) | 2.0 (0 to 4.0) | 3.0 (1.0 to 5.0) | 3.0 (1.0 to 6.0) |

| DASH diet scoref | ||||

| Total No. | 2067 | 422 | 2345 | 750 |

| Mean (SD) | 13.4 (4.3) | 14.9 (4.3) | 12.9 (4.3) | 14.5 (4.3) |

| Mediterranean diet scoreg | ||||

| Total No. | 2043 | 411 | 2322 | 735 |

| Mean (SD) | 4.5 (1.7) | 4.2 (1.7) | 4.6 (1.7) | 4.5 (1.8) |

| Southern diet scoreh | ||||

| Total No. | 2067 | 422 | 2345 | 750 |

| Mean (SD) | −0.3 (0.9) | 0.8 (1.2) | −0.6 (0.8) | 0.2 (1.0) |

| Ratio of sodium to potassiumi | ||||

| Total No. | 2067 | 422 | 2345 | 750 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.9 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.3) | 0.8 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.3) |

Abbreviations: CESD-4, 4-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale; DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension; IQR, interquartile range.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Range from 11.5 to 59.9; higher scores are associated with greater adiposity.

Range from 48.3 to 183.5; higher scores represent larger waist circumference.

Defined according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism as ≥7 drinks per week in women or ≥14 drinks per week in men.

Range from 0 to 12; higher scores represent more depressive symptoms.

Range from 0 to 16; higher scores represent more perceived stress.

Original score subtracted from 38; range from 0 to 29; higher scores reflect being less compliant with the diet.

Original score subtracted from 9; range from 0 to 9; higher scores reflect being less compliant with the diet.

Range from −4.5 to 8.2; higher scores reflect being more compliant with the diet.

Range from 0.3 to 2.5; higher scores represent a greater intake of sodium relative to potassium.

The incidence of hypertension during the median 9.4-year follow-up was 46% (95% CI, 44%-49%) among black participants and 33% (95% CI, 32%-34%) among white participants. At baseline, the mean systolic blood pressure level was 117 mm Hg (SD, 12 mm Hg) in women and 120 mm Hg (SD, 10 mm Hg) in men and the mean diastolic blood pressure level was 73 mm Hg (SD, 8 mm Hg) in women and 74 mm Hg (SD, 7 mm Hg) in men. With inclusion at baseline limited to those without hypertension, no participants were taking an antihypertensive medication.

At the follow-up visit, the mean systolic blood pressure level was 120 mm Hg (SD, 14 mm Hg) in women and 122 mm Hg (SD, 13 mm Hg) in men and the mean diastolic blood pressure was 72 mm Hg (SD, 8 mm Hg) in women and 73 mm Hg (SD, 8 mm Hg) in men; and 32.6% of women and 30.8% of men were taking an antihypertensive medication. After adjustment for age group and baseline systolic blood pressure, the OR of incident hypertension for black participants compared with white participants was 1.35 (95% CI, 1.12-1.61) for men and 1.73 (95% CI, 1.49-2.01) for women.

Mediating Factors Among Men

The age-adjusted least-squares mean for the Southern dietary pattern was −0.26 (95% CI, −0.31 to −0.21) among white men vs 0.81 (95% CI, 0.72 to 0.90) among black men; the age-adjusted difference in means was −1.07 (95% CI, −1.17 to −0.97) (Table 3). There also was a significant association between the Southern diet and the risk of incident hypertension (adjusted OR, 1.16 [95% CI, 1.06 to 1.27]; incidence proportion at the 25th percentile of diet score, 32.4% [95% CI, 29.9% to 34.9%] and at the 75th percentile of diet score, 36.1% [95% CI, 33.8% to 38.3%]; absolute risk difference, 3.7% [95% CI, 1.4% to 6.2%]). The Southern dietary pattern was the largest mediating factor for differences in the incidence of hypertension, accounting for 51.6% (95% CI, 18.8% to 84.4%) of the higher risk of incident hypertension among black men (Figure 2).

Table 3. Association of Risk Factors With Hypertension Among Men.

| Potential Mediating Factor | Sample Size | Age-Adjusted Least-Squares Mean (95% CI)a | Age-Adjusted Difference Between White and Black Participants (95% CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI)b | Adjusted Incidence Proportion (95% CI) | Absolute Risk Difference in Incidence (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Black | White Men | Black Men | Factor Absent or 25th Percentile of Factor | Factor Present or 75th Percentile of Factor | ||||

| Education level ≤high school | 2430 | 695 | 0.20 (0.18 to 0.22) | 0.38 (0.35 to 0.42) | −0.18 (−0.22 to −0.15) | 1.22 (1.02 to 1.47)c | 34.0 (32.0 to 35.9) | 38.7 (34.6 to 42.4) | 4.6 (0.1 to 8.8) |

| Income ≤$35 000 | 2234 | 637 | 0.23 (0.21 to 0.25) | 0.42 (0.39 to 0.46) | −0.19 (−0.23 to −0.15) | 1.20 (1.00 to 1.45)c | 34.3 (32.2 to 36.4) | 38.6 (34.7 to 42.6) | 4.3 (0 to 8.9) |

| Body mass indexd | 2426 | 693 | 27.3 (27.1 to 27.6) | 27.6 (27.2 to 27.9) | −0.3 (−0.7 to 0.1) | 1.22 (1.13 to 1.32)e | 32.1 (30.5 to 35.0) | 37.3 (35.8 to 40.3) | 5.2 (3.2 to 7.7) |

| Waist circumference, cm | 2427 | 694 | 96.8 (96.3 to 97.4) | 95.7 (94.8 to 96.6) | 1.2 (0.1 to 2.2) | 1.18 (1.09 to 1.27)e | 32.5 (30.5 to 34.6) | 36.9 (34.9 to 39.2) | 4.4 (2.3 to 9.2) |

| Heavy alcohol usef | 2398 | 677 | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.05) | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.05) | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.03) | 0.97 (0.67 to 1.40)c | 34.8 (33.0 to 36.8) | 34.1 (26.4 to 42.7) | −0.8 (−8.6 to 7.9) |

| Does not exercise | 2405 | 687 | 0.20 (0.18 to 0.22) | 0.24 (0.21 to 0.28) | −0.04 (−0.08 to 0) | 0.98 (0.81 to 1.18)c | 35.0 (32.9 to 36.9) | 34.5 (30.8 to 38.1) | −0.5 (−4.5 to 3.7) |

| Depression scale score (CESD-4)g | 2410 | 689 | 0.57 (0.51 to 0.64) | 0.91 (0.80 to 1.03) | −0.34 (−0.47 to −0.21) | 1.05 (0.97 to 1.13)e | 34.6 (32.2 to 36.5) | 34.3 (33.2 to 37.1) | 0.7 (−0.4 to 1.9) |

| Perceived Stress Scale scoreh | 2430 | 695 | 2.40 (2.28 to 2.51) | 2.86 (2.66 to 3.05) | −0.46 (−0.69 to −0.23) | 1.00 (0.92 to 1.08)e | 35.2 (32.5 to 37.6) | 35.0 (32.9 to 37.0) | −0.2 (−2.8 to 2.5) |

| DASH diet scorei | 2067 | 422 | 13.3 (13.1 to 13.6) | 14.7 (14.3 to 15.1) | −1.4 (−1.8 to −0.9) | 1.05 (0.96 to 1.15)e | 33.5 (30.9 to 36.3) | 35.3 (35.3 to 37.8) | 1.8 (−1.2 to 4.6) |

| Mediterranean diet scorej | 2043 | 411 | 4.47 (4.38 to 4.56) | 4.19 (4.02 to 4.36) | 0.28 (0.09 to 0.48) | 1.01 (0.92 to 1.10)e | 34.1 (31.7 to 36.7) | 34.3 (34.3 to 37.0) | 0.2 (−3.1 to 3.3) |

| Southern diet scorek | 2067 | 422 | −0.26 (−0.31 to −0.21) | 0.81 (0.72 to 0.90) | −1.07 (−1.17 to −0.97) | 1.16 (1.06 to 1.27)e | 32.4 (29.9 to 34.9) | 36.1 (33.8 to 38.3) | 3.7 (1.4 to 6.2) |

| Ratio of sodium to potassiuml | 2067 | 422 | 0.89 (0.87 to 0.98) | 0.98 (0.95 to 1.00) | −0.09 (−0.12 to −0.06) | 1.11 (1.01 to 1.20)e | 32.9 (30.4 to 35.5) | 35.8 (33.5 to 38.2) | 2.9 (0.4 to 5.5) |

Abbreviations: CESD-4, 4-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension.

For dichotomous variables, the data have been scored 0 for “no” and 1 for “yes”; therefore, the mean is equivalent to the proportion.

Adjusted for age, race, and baseline systolic blood pressure for the risk factor of incident hypertension. For example, data on education were available on 2430 white participants and 695 black participants. The age-adjusted estimate of the proportion with an education level ≤high school was 20% for white participants (95% CI, 18% to 22%) and 38% for black participants (95% CI, 35% to 42%), which differed by 18% (95% CI, 15% to 22%). The odds of developing hypertension during follow-up was 1.22-times higher for those with an education level ≤high school (relative to those with >high school education level); 38.7% (95% CI, 34.6% to 42.4%) of those with an education level ≤high school developed hypertension vs 34.0% (95% CI, 32.0% to 35.9%) of those with >high school education level developed hypertension, which differed by 4.6% (95% CI, 0.1% to 8.8%).

Expressed as the difference in a dichotomous predictor.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Expressed for a 1-SD difference in a continuous predictor.

Defined according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism as ≥7 drinks per week in women or ≥14 drinks per week in men.

Range from 0 to 12; higher scores represent more depressive symptoms.

Range from 0 to 16; higher scores present more perceived stress.

Original score subtracted from 38; range from 0 to 29; higher scores reflect being less compliant with the diet.

Original score subtracted from 9; range from 0 to 9; higher scores reflect being less compliant with the diet.

Range from −4.5 to 8.2; higher scores reflect being more compliant with the diet.

Range from 0.3 to 2.5; higher scores represent a greater intake of sodium relative to potassium.

Figure 2. Percentage of Mediation for the Excess Risk of Incident Hypertension in Black Men and Women.

A 0% mediation means none of the association between race and incident hypertension is attributable to the factor (eg, the entire association between race and incident hypertension is a direct effect), whereas 100% means that race is fully mediated by the factor (eg, the total association is an indirect association with the mediating factor). There was a negative mediation for some factors (eg, for waist circumference in men). This implies that adjustment for this factor resulted in an exacerbation of the risk difference for incident hypertension with adjustment for this factor.

aCalculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

bFor men, higher waist circumference was positively associated with the risk of incident hypertension (odds ratio, 1.18 [95% CI, 1.09-1.27]; incidence proportions at 25th percentile of waist circumference of 32.5% [95% CI, 30.5%-35.0%] and at the 75th percentile of waist circumference of 36.9% [95% CI, 34.9%-39.2%]; and an absolute difference 4.4% [95% CI, 2.3%-9.2%]), but white men had a larger waist than black men; therefore, the estimated difference between black and white adults became larger when adjusted for waist circumference.

cThe 4-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CESD-4) was used; higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms.

dHigher scores reflect more perceived stress.

eLower scores indicate less adherence to the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet.

fLower scores indicate less adherence to the Mediterranean diet.

gHigher scores indicate more adherence to the Southern diet.

hHigher scores indicate a greater intake of sodium relative to potassium.

The age-adjusted prevalence of an education level of high school or less was 20% (95% CI, 18% to 22%) for white men and 38% (95% CI, 35% to 42%) for black men, and had an age-adjusted difference of 18% (95% CI, 15% to 22%). In addition, a high school education or less was significantly associated with incident hypertension (adjusted OR, 1.22 [95% CI, 1.02 to 1.47]). The incidence proportion for those without a high school degree was 34.0% (95% CI, 32.0% to 35.9%) and was 38.7% (95% CI, 34.6% to 42.4%) for those with a high school degree (absolute risk difference, 4.6% [95% CI, 0.1% to 8.8%]) and accounted for 12.3% (95% CI, 0.6% to 23.9%) of the excess risk of hypertension among black men.

The age-adjusted mean dietary ratio of sodium to potassium intake was 0.89 (95% CI, 0.87 to 0.98) for white men and 0.98 (95% CI, 0.95 to 1.00) for black men (age-adjusted difference, −0.09 [95% CI, −0.12 to −0.06]). The ratio of sodium to potassium also was associated with incident hypertension (OR, 1.11 [95% CI, 1.01 to 1.20]; incidence proportion at 25th percentile, 32.9% [95% CI, 30.4% to 35.5%] and the 75th percentile, 35.8% [95% CI, 33.5% to 38.2%]; absolute risk difference, 2.9% [95% CI, 0.4% to 5.5%]). Together, these accounted for 12.3% (95% CI, 1.1% to 22.8%) of the excess risk of hypertension among black men.

Higher BMI was related to the risk of incident hypertension (Table 3), but because the mean BMI was similar among black and white men, it was not a mediating factor for the excess risk of hypertension among black men (Figure 2). A larger waist circumference was related to risk of incident hypertension, but white men had larger waist circumferences than black men, so adjustment for waist circumference significantly increased the risk of incident hypertension among black men by 8.4% (95% CI, 1.5% to 15.4%). The Perceived Stress Scale score and less adherence to the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet were not significantly associated with incident hypertension (Table 3), and thus did not mediate the risk of incident hypertension among black men. Less adherence to the Mediterranean diet was more prevalent among white men than black men, but was not significantly associated with the risk of incident hypertension. Prevalence of heavier alcohol use did not differ between white men and black men and was not associated with incident hypertension.

Mediating Factors Among Women

A larger number of factors mediated the higher risk for hypertension among black women compared with white women (Table 4 and Figure 2). Similar to men, the single largest mediating factor was the Southern dietary pattern; the age-adjusted mean dietary score was −0.57 (95% CI, −0.61 to −0.54) among white women and 0.27 (95% CI, 0.20 to 0.33) among black women and the age-adjusted difference in means was −0.84 (95% CI, −0.91 to −0.77). The Southern diet score was significantly associated with incident hypertension (adjusted OR, 1.17 [95% CI, 1.08 to 1.28]; incidence proportion at the 25th percentile of diet score, 31.0% [95% CI, 28.8% to 33.2%], and at the 75th percentile, 34.8% [95% CI, 32.5% to 36.8%]; absolute risk difference, 3.8% [95% CI, 1.5% to 5.8%]), and accounted for 29.2% (95% CI, 13.4% to 44.9%) of the risk of hypertension among black women.

Table 4. Association of Risk Factors With Hypertension Among Women.

| Sample Size | Age-Adjusted Least-Squares Mean (95% CI)a | Difference Between White and Black Participants (95% CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI)b | Adjusted Proportion (95% CI) | Absolute Risk Difference in Incidence (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Black | White Women | Black Women | Factor Absent or 25th Percentile of Factor | Factor Present or 75th Percentile of Factor | ||||

| Education level ≤high school | 2660 | 1112 | 0.27 (0.25 to 0.29) | 0.35 (0.32 to 0.38) | −0.08 (−0.12 to −0.05) | 1.40 (1.20 to 1.64)c | 32.4 (30.4 to 34.3) | 40.1 (36.9 to 43.4) | 7.7 (4.2 to 11.2) |

| Income ≤$35 000 | 2275 | 993 | 0.40 (0.38 to 0.43) | 0.54 (0.51 to 0.57) | −0.13 (−0.17 to −0.10) | 1.52 (1.30 to 1.79)c | 31.0 (28.7 to 33.3) | 40.6 (40.6 to 37.6) | 9.7 (5.9 to 13.3) |

| Body mass indexd | 2656 | 1106 | 26.7 (26.5 to 27.0) | 30.0 (29.7 to 30.4) | −3.3 (−3.8 to −2.9) | 1.25 (1.16 to 1.35)e | 30.8 (27.7 to 32.9) | 37.0 (34.9 to 39.2) | 6.2 (4.1 to 8.4) |

| Waist circumference, cm | 2641 | 1105 | 85.0 (84.3 to 85.6) | 91.9 (91.0 to 92.8) | −6.9 (−8.0 to −5.8) | 1.25 (1.16 to 1.34)e | 30.7 (28.7 to 32.9) | 37.7 (35.3 to 39.8) | 7.0 (4.5 to 9.2) |

| Heavy alcohol usef | 2631 | 1088 | 0.05 (0.04 to 0.06) | 0.02 (0.01 to 0.03) | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.05) | 0.93 (0.65 to 1.32)c | 34.3 (32.6 to 36.2) | 32.7 (25.8 to 40.4) | −1.6 (−8.9 to 6.0) |

| Does not exercise | 2621 | 1100 | 0.29 (0.27 to 0.31) | 0.33 (0.30 to 0.36) | −0.05 (−0.08 to −0.01) | 1.31 (1.12 to 1.53)c | 32.6 (30.6 to 34.6) | 38.8 (35.8 to 41.8) | 6.2 (2.9 to 9.6) |

| Depression scale (CESD-4) scoreg | 2644 | 1097 | 0.98 (0.89 to 1.06) | 1.17 (1.05 to 1.30) | −0.20 (−0.35 to −0.04) | 1.12 (1.04 to 1.20)e | 33.1 (31.2 to 35.2) | 34.4 (32.6 to 36.2) | 1.3 (0.5 to 2.1) |

| Perceived Stress Scale scoreh | 2660 | 1112 | 3.18 (3.05 to 3.30) | 3.44 (3.26 to 3.61) | −0.26 (−0.48 to −0.05) | 1.03 (0.96 to 1.10)e | 34.0 (31.9 to 36.3) | 34.9 (32.9 to 36.9) | 0.9 (−1.6 to 3.3) |

| DASH diet scorei | 2345 | 750 | 12.9 (12.7 to 13.1) | 14.4 (14.1 to 14.8) | −1.5 (−1.9 to −1.1) | 1.20 (1.11 to 1.30)e | 29.9 (27.6 to 32.3) | 35.4 (33.1 to 37.8) | 5.5 (3.3 to 8.1) |

| Mediterranean diet scorej | 2322 | 735 | 4.62 (4.54 to 4.70) | 4.51 (4.38 to 4.64) | 0.11 (−0.04 to 0.27) | 1.17 (1.08 to 1.30)e | 29.6 (27.1 to 31.9) | 35.6 (33.3 to 38.1) | 6.0 (3.2 to 9.1) |

| Southern diet scorek | 2345 | 750 | −0.57 (−0.61 to −0.54) | 0.27 (0.20 to 0.33) | −0.84 (−0.91 to −0.77) | 1.17 (1.08 to 1.28)e | 31.0 (28.8 to 33.2) | 34.8 (32.5 to 36.8) | 3.8 (1.5 to 5.8) |

| Ratio of sodium to potassiuml | 2345 | 750 | 0.81 (0.79 to 0.82) | 0.88 (0.86 to 0.90) | −0.08 (−0.10 to −0.06) | 1.13 (1.04 to 1.22)e | 31.1 (29.1 to 33.5) | 34.5 (32.2 to 36.8) | 3.3 (1.1 to 5.5) |

Abbreviations: CESD-4, 4-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension.

For dichotomous variables, the data have been scored 0 for “no” and 1 for “yes”; therefore, the mean is equivalent to the proportion.

Adjusted for age, race, and baseline systolic blood pressure for the risk factor of incident hypertension. For example, data on education were available on 2430 white participants and 695 black participants. The age-adjusted estimate of the proportion with an education level ≤high school was 20% for white participants (95% CI, 18% to 22%) and 38% for black participants (95% CI, 35% to 42%), which differed by 18% (95% CI, 15% to 22%). The odds of developing hypertension during follow-up was 1.22-times higher for those with an education level ≤high school (relative to those with >high school education level); 38.7% (95% CI, 34.6% to 42.4%) of those with an education level ≤high school developed hypertension vs 34.0% (95% CI, 32.0% to 35.9%) of those with >high school education level developed hypertension, which differed by 4.6% (95% CI, 0.1% to 8.8%).

Expressed as the difference in a dichotomous predictor.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Expressed for a 1-SD difference in a continuous predictor.

Defined according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism as ≥7 drinks per week in women or ≥14 drinks per week in men.

Range from 0 to 12; higher scores represent more depressive symptoms.

Range from 0 to 16; higher scores present more perceived stress.

Original score subtracted from 38; range from 0 to 29; higher scores reflect being less compliant with the diet.

Original score subtracted from 9; range from 0 to 9; higher scores reflect being less compliant with the diet.

Range from −4.5 to 8.2; higher scores reflect being more compliant with the diet.

Range from 0.3 to 2.5; higher scores represent a greater intake of sodium relative to potassium.

Black women had a higher mean BMI and larger waist circumferences than white women, and both waist circumference and BMI had a significant association with incident hypertension. Among black women, BMI was the second largest mediating factor for hypertension and accounted for 18.3% (95% CI, 11.9% to 24.6%) of the risk and larger waist circumference was the third largest mediating factor and accounted for 15.2% (95% CI, 9.8% to 20.6%) of the risk. Other factors mediating the excess risk of hypertension among black women included less adherence to the DASH diet (11.2%), income of $35 000 or less (9.3%), higher dietary ratio of sodium to potassium (6.8%), and education level of high school or less (4.1%).

The Perceived Stress Scale score did not attenuate the higher risk of hypertension among black women because of a lack of association with the risk of incident hypertension (Figure 2 and Table 4). Less adherence with the Mediterranean diet was associated with risk of incident hypertension but did not differ between black and white women.

Exploratory, Sensitivity, and Post Hoc Analyses

Exploratory mediation analysis of 9 factors assessed only at follow-up suggested that low mobility may be a significant mediator in men and low-quality neighborhood score may be a significant mediator in both men and women (eTables 1 through 4 and the eFigure in Supplement 1). A sensitivity analysis using inverse probability weighting provided nearly identical results as the primary analysis, with a correlation coefficient of 0.99 for the primary analysis (additional information appears in Supplement 1).

The post hoc analyses assessing effect modification of the mediation by age suggested a stronger association between dietary measures and the increased risk of hypertension among black participants at younger ages, with only modest effect modification by age for the other factors (eTables 5, 6, and 7 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

A high intake of the Southern diet was the largest mediator of the difference between black and white participants in the incidence of hypertension for both men and women. The Southern diet, defined previously in the REGARDS study,13 includes high intake of fried foods, organ meats, processed meats, egg and egg dishes, added fats, high-fat dairy foods, sugar-sweetened beverages, and bread. In other research, this dietary pattern was associated with increased risk of incident stroke,13 coronary heart disease,16 end-stage renal disease and chronic kidney disease,17 sepsis,18 cancer mortality,19 and cognitive decline.20 The Southern diet also has been shown to be a large mediating factor for the difference in stroke risk between black and white individuals.13

Among both men and women, a high dietary ratio of sodium to potassium was a significant mediating factor. Among women, less adherence to the DASH diet was a significant mediating factor. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute high blood pressure education program concluded randomized clinical trial evidence shows a delay or prevention of hypertension with dietary interventions including reduced sodium intake, maintenance of adequate intake of potassium, and consumption of a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products, and a diet reduced in saturated and total fat.21 The American Heart Association also has issued a scientific statement with evidence that dietary interventions can prevent or delay the development of hypertension.22

An education level of high school or less was a statistically significant mediating factor of incident hypertension among both men and women. Low educational attainment is associated with poorer health outcomes,23 shorter life expectancy,24 and higher systolic blood pressure and incidence of hypertension.25,26,27,28,29,30 Low education level may be linked with hypertension through mechanisms including higher job-related and family-related stress and poorer diet.31 A low-quality neighborhood score was the only other significant mediator of the difference between black and white participants in incident hypertension for both men and women.

The findings herein identified more mediating factors of the racial difference in incident hypertension in women than men. This may be partially attributable to an observed stronger association of race with incident hypertension among women than men that would provide greater statistical power to detect mediating factors.

For both men and women, higher BMI and greater waist circumference were associated with incident hypertension. However, neither BMI nor waist circumference was higher for black men than white men, and thus neither of these factors mediated the risk of incident hypertension for men. In contrast, black women had higher BMI and greater waist circumference than white women, and both BMI and waist circumference provided statistically significant mediation.

Among men, a higher BMI was associated with incident hypertension but did not differ in the prevalence of hypertension between black and white men. Interventions to lower BMI would benefit both black and white adults; however, based on the findings of this study, lowering BMI would not be expected to reduce the racial disparity in hypertension.

For other mediating factors, there were significant differences in the prevalence of the exposure for black and white participants, but no association with incident hypertension. For women, the other mediating factors included stress. For men, the other mediating factors included depressive symptoms, stress, and low DASH diet score. Findings suggest that an intervention aimed at these factors may not reduce incident hypertension among either the black or white populations.

The greatest strengths of this research are that the large REGARDS cohort was well characterized at 2 time points separated by approximately 10 years, and that a systematic assessment of risk factors for hypertension was carried out. Although the representativeness of the study population generally has a smaller effect on the assessment of associations than the estimation of the population prevalence of conditions, the REGARDS cohort oversampled residents of the 8-state southeastern stroke belt region of the United States.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, approximately half of the REGARDS cohort did not have a follow-up visit, 16% had died, and 24% either withdrew from follow-up or declined the visit. Initially, competing cause models32 had been considered to account for those who died; however, with the focus of this study on the etiologic effects, the use of these models would have been inappropriate.33 Use of inverse probability weighting analysis15 to account for differential attrition from the study was evaluated, and had little effect on the results. Second, as in all clinical research, measurement error and misclassification of the potential meditating factors occurs. Such misclassification would generally lead to underestimation of the effects of potential mediating factors,34 so the reported estimates of the mediating effects could be underestimates.

Conclusions

In a mediation analysis comparing incident hypertension among black adults vs white adults in the United States, key factors statistically mediating the racial difference for both men and women included Southern diet score, dietary ratio of sodium to potassium, and education level. Among women, waist circumference and BMI also were key factors.

eAnalysis 1. Exploratory mediation analysis of 9 factors measured only at follow‐up

eAnalysis 2. Sensitivity analysis comparing unweighted mediation analysis (in manuscript) to analysis using inverse probability weighted to account for attrition bias

eMethods. Details of scoring for dietary scales

eTable 1. Description of potential mediating factors measured only at follow‐up

eTable 2. Participant characteristics by gender and race

eTable 3. Mediation analysis for men for factors measured only at follow‐up

eTable 4. Mediation analysis for women for factors measured only at follow‐up

eTable 5. Comparison of mediation estimates using the unweighted approach presented in the manuscript and in the supplemental material with estimates using inverse probability weighting to account for potential attrition bias

eTable 6. Mediation analysis for men stratified by age for factors proving significant in pooled analysis

eTable 7. Mediation analysis for women stratified by age for factors proving significant in pooled analysis

eFigure. Percent mediation (with 95% confidence interval) of the excess risk of incident hypertension in blacks for men (red) and women (blue) for factors measured only at follow‐up

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Boscardin WJ, Ettner SL. Contribution of major diseases to disparities in mortality. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(20):1585-1592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen L, Simonsen N, Liu L. Racial differences of pediatric hypertension in relation to birth weight and body size in the United States. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132606. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carson AP, Howard G, Burke GL, Shea S, Levitan EB, Muntner P. Ethnic differences in hypertension incidence among middle-aged and older adults: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Hypertension. 2011;57(6):1101-1107. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.168005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howard G, Safford MM, Moy CS, et al. Racial differences in the incidence of cardiovascular risk factors in older black and white adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(1):83-90. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuchs FD. Why do black Americans have higher prevalence of hypertension?: an enigma still unsolved. Hypertension. 2011;57(3):379-380. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.163196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howard VJ, Cushman M, Pulley L, et al. The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25(3):135-143. doi: 10.1159/000086678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mackinnon DP, Warsi G, Dwyer JH. A simulation study of mediated effect measures. Multivariate Behav Res. 1995;30(1):41. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3001_3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385-401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385-396. doi: 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrington J, Fitzgerald AP, Layte R, Lutomski J, Molcho M, Perry IJ. Sociodemographic, health and lifestyle predictors of poor diets. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(12):2166-2175. doi: 10.1017/S136898001100098X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Block G, Hartman AM, Dresser CM, Carroll MD, Gannon J, Gardner L. A data-based approach to diet questionnaire design and testing. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124(3):453-469. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2599-2608. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Judd SE, Gutiérrez OM, Newby PK, et al. Dietary patterns are associated with incident stroke and contribute to excess risk of stroke in black Americans. Stroke. 2013;44(12):3305-3311. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:593-614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cole SR, Hernán MA. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(6):656-664. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shikany JM, Safford MM, Newby PK, Durant RW, Brown TM, Judd SE. Southern dietary pattern is associated with hazard of acute coronary heart disease in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Study. Circulation. 2015;132(9):804-814. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gutiérrez OM, Muntner P, Rizk DV, et al. Dietary patterns and risk of death and progression to ESRD in individuals with CKD: a cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(2):204-213. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gutiérrez OM, Judd SE, Voeks JH, et al. Diet patterns and risk of sepsis in community-dwelling adults: a cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:231. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0981-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akinyemiju T, Moore JX, Pisu M, et al. A prospective study of dietary patterns and cancer mortality among blacks and whites in the REGARDS cohort. Int J Cancer. 2016;139(10):2221-2231. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearson KE, Wadley VG, McClure LA, Shikany JM, Unverzagt FW, Judd SE. Dietary patterns are associated with cognitive function in the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) cohort. J Nutr Sci. 2016;5:e38. doi: 10.1017/jns.2016.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whelton PK, He J, Appel LJ, et al. ; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee . Primary prevention of hypertension: clinical and public health advisory from the National High Blood Pressure Education Program. JAMA. 2002;288(15):1882-1888. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Appel LJ, Brands MW, Daniels SR, Karanja N, Elmer PJ, Sacks FM; American Heart Association . Dietary approaches to prevent and treat hypertension: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2006;47(2):296-308. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000202568.01167.B6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eggen AE, Mathiesen EB, Wilsgaard T, Jacobsen BK, Njølstad I. Trends in cardiovascular risk factors across levels of education in a general population: is the educational gap increasing? the Tromsø study 1994-2008. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(8):712-719. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-203428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan RM, Howard VJ, Safford MM, Howard G. Educational attainment and longevity: results from the REGARDS US national cohort study of blacks and whites. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(5):323-328. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conen D, Glynn RJ, Ridker PM, Buring JE, Albert MA. Socioeconomic status, blood pressure progression, and incident hypertension in a prospective cohort of female health professionals. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(11):1378-1384. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loucks EB, Abrahamowicz M, Xiao Y, Lynch JW. Associations of education with 30 year life course blood pressure trajectories: Framingham Offspring Study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:139. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diez Roux AV, Chambless L, Merkin SS, et al. Socioeconomic disadvantage and change in blood pressure associated with aging. Circulation. 2002;106(6):703-710. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000025402.84600.CD [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hubert HB, Eaker ED, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP. Life-style correlates of risk factor change in young adults: an eight-year study of coronary heart disease risk factors in the Framingham offspring. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;125(5):812-831. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strand BH, Steingrímsdóttir OA, Grøholt EK, Ariansen I, Graff-Iversen S, Næss Ø. Trends in educational inequalities in cause specific mortality in Norway from 1960 to 2010: a turning point for educational inequalities in cause specific mortality of Norwegian men after the millennium? BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1208. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yan LL, Liu K, Daviglus ML, et al. Education, 15-year risk factor progression, and coronary artery calcium in young adulthood and early middle age: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study. JAMA. 2006;295(15):1793-1800. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.15.1793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meschia JF, Bushnell C, Boden-Albala B, et al. ; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology; Council on Hypertension . Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(12):3754-3832. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496-509. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Austin PC, Lee DS, Fine JP. Introduction to the analysis of survival data in the presence of competing risks. Circulation. 2016;133(6):601-609. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Armstrong BG. The effects of measurement errors on relative risk regressions. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(6):1176-1184. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAnalysis 1. Exploratory mediation analysis of 9 factors measured only at follow‐up

eAnalysis 2. Sensitivity analysis comparing unweighted mediation analysis (in manuscript) to analysis using inverse probability weighted to account for attrition bias

eMethods. Details of scoring for dietary scales

eTable 1. Description of potential mediating factors measured only at follow‐up

eTable 2. Participant characteristics by gender and race

eTable 3. Mediation analysis for men for factors measured only at follow‐up

eTable 4. Mediation analysis for women for factors measured only at follow‐up

eTable 5. Comparison of mediation estimates using the unweighted approach presented in the manuscript and in the supplemental material with estimates using inverse probability weighting to account for potential attrition bias

eTable 6. Mediation analysis for men stratified by age for factors proving significant in pooled analysis

eTable 7. Mediation analysis for women stratified by age for factors proving significant in pooled analysis

eFigure. Percent mediation (with 95% confidence interval) of the excess risk of incident hypertension in blacks for men (red) and women (blue) for factors measured only at follow‐up

Data Sharing Statement