Abstract

Interstitial macrophages (IMs) are present in multiple organs. Although there is limited knowledge of the unique functional role IM subtypes play, macrophages, in general, are known for their contribution in homeostatic tissue maintenance and inflammation such as clearing pathogens and debris and secreting inflammatory mediators and growth factors. IM subtypes have been identified in the heart, skin, and gut, and more recently we identified three distinct IMs in the lung. IMs express on their surface high levels of MerTK, CD64, and CD11b, with differences in CD11c, CD206, and MHC II expression, and referred to the three pulmonary IM subtypes as IM1 (CD11cloCD206+MHCIIlo), IM2 (CD11cloCD206+MHCIIhi), and IM3 (CD11chiCD206loMHCIIhi). In this chapter, we highlight how to extract IMs from the lung using three different digestion enzymes: elastase, collagenase D, and Liberase TM. Of these three commonly used enzymes, Liberase TM was the most effective at IM extraction, particularly IM3. Furthermore, alternative staining strategies to identify IMs were examined, which included CD64, MerTK, F4/80, and Tim4. Thus, future studies highlighting the functional role of IM subtypes will help further our understanding of how tissue homeostasis is maintained and inflammatory conditions are induced and resolved.

Keywords: Mononuclear phagocytes, Dendritic cells, Monocytes, Interstitial macrophages, Alveolar macrophages, Pulmonary, Lung

1. Introduction

To date, there are four known pulmonary macrophage populations in the steady state. One is the alveolar macrophage, which is a tissue-specific macrophage that only exists in the lung, specifically in the luminal space of the alveoli and thus supports types 1 and 2 epithelial cell functions. In addition to alveolar macrophages, there are three distinct interstitial macrophages (IMs), which are located in the bronchial interstitia along with other leukocytes [1]. However, which hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cell type IMs support during homeostasis and what they functionally do is currently unclear. In the steady state there are four resident macrophages, and during inflammation there are additional macrophages referred to as recruited macrophages [2–4]. However, whether recruited macrophages, like IMs, contain different macrophage subtypes during the inflammatory process is still unknown.

Undoubtedly, the macrophage population in the lung and other organs is far more complex than originally thought. Therefore, this chapter aims to compare and demonstrate how various digestion enzymes, specifically collagenase D, elastase, and Liberase TM, isolate IMs from the lung. Collagenase D is a type I collagenase, elastase is a serine protease, and Liberase TM is a highly purified mixture of collagenases I and II. Lastly, along with an analysis of tissue digestion, we highlighted different staining strategies to identify IMs. Overall, this chapter is a resource to identify and analyze the currently understudied IMs that not only exist in the lung but in other organs as well.

2. Materials

2.1. Antibody Clones Used for Staining

The following antibody clones (Table 1) are the ones most commonly used in our laboratory. Alternative florescent conjugates can also be used.

Table 1.

Antibody clones used to stain interstitial macrophages

| Antigen | Clone | Conjugate | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD11c | N418 | PE-cy7 | 1:100 |

| CD206 | MR5D3, C068C2 | FITC | 1:100 |

| F4/80 | CI: A3–1 | FITC or PE | 1:50 |

| MHCII | M5/114.15.2 | APC-Cy7, PO | 1:300 |

| CD11b | Ml/70 | Percp5.5 | 1:200 |

| Ly6C | HK1.4 | BV605 | 1:200 |

| MertK | BAF591 (RnD systems) | Biotin | 1:100 |

| CD64 | X54–5/7.1BD | AF647, APC | 1:100 |

| CD4 | GK1.5 | BV510 | 1:200 |

| Tim4 | 54 (RMT4–54) | PE | 1:100 |

| Siglec F | E50–2440 | PE | 1:100 |

| CCR2 | 475301 | PE | 1:100 |

| CD45 | 30-F11 | FITC, PE or APC | 1:100 |

2.2. Lung Single-Cell Suspension

Instruments: Scissors, blunt-curve forceps, straight-tip forceps.

18- and 26-gauge needle.

1, 3, and 30 mL syringe.

Tissue culture plates: 35 mm × 10 mm round culture dishes or 12-well tissue culture plate.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) tubes.

Glass Pasteur pipettes and a rubber bulb.

1× PBS without calcium and magnesium pH 7.4.

Anti-CD45 microbeads and columns.

MACS from Miltenyi buffer: 1× Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA).

1× Hanks’ buffered salt solution (HBSS) without calcium and magnesium.

100 mM EDTA pH 8.0.

Hanks’ buffered salt solution complete buffer (HBSS complete): HBSS without calcium and magnesium, 0.2% BSA (Sigma, USA), and 0.5 mM EDTA.

Make a 10× stock solution of collagenase D in 1× RPMI, 37.5 mL of Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI) with 1 g of collagenase D from Roche.

Make a 2 mg/mL stock solution of Liberase TM from Roche. Aliquot 1–2 mL stock solutions and store at −20°C.

2.3. Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) Staining for Single-Cell Suspension of Lung

HBSS complete.

FACS tubes.

Machines: Centrifuge and FACS sorter and analyzer.

3. Methods

3.1. Bronchoalveolar Lavage

Euthanize mice according to the standard protocol prescribed by the institution (see Note 1).

Expose the trachea by making a vertical midline incision and spread the skin.

Under the skin, there are two large masses. These are the submaxillary glands. Gently separate the glands from the midline with forceps (do not cut to avoid bleeding). The trachea will be easily seen and exposed.

Grab the outer fascial membrane covering the trachea with forceps. Carefully cut it away to expose the cartilage rings of the trachea.

Position the mouse upright and insert one side of a blunt forceps behind the trachea.

Through the largest uppermost cartilage ring, insert an 18-gauge needle, with the bevel facing outward. Attach a 3 mL syringe containing 1 mL of HBSS complete (or 1× PBS alone if lung digestion follows). Do not insert the needle too deep into the trachea. Only insert it far enough to sufficiently cover the needle opening. After needle insertion, clamp down on the needle with the other side of the blunt forceps to hold the needle in place.

Lavage the lungs four times with 1 mL of HBSS complete or 1× PBS. Do not add more volume to the syringe.

Collect lavage fluid in a 5 mL FACS tube and centrifuge at 300 × g for 5 min at 4°C.

Remove supernatant and place cells on ice.

Alveolar macrophages (AM) can be stained with an antibody cocktail containing the following antibodies: anti-F4/80 FITC, anti-CD11c PECy7, anti-CD11b PB, anti-Ly6C PerCpCy5.5, anti-CD64 APC, anti-MHC II PO, anti-Siglec F PE, and anti-Ly6G APC-Cy7. Add antibody cocktail for at least 45 min for optimal cell separation during FACS analysis. Detailed analysis of AM is beyond the scope of this chapter.

3.2. Single-Cell Suspension of Lung After Enzymatic Digestion

Expose the lungs carefully by opening the abdominal cavity. Make a careful excision in the diaphragm and perfuse the lung through the heart with 1× PBS, to blanch the lungs.

Remove lung, place the lung on a glass microscope slide, cut and mince the lung into very tiny pieces with scissors. Then, place the lung into the digestion buffer.

For tissue digestion: make fresh 2× Collagenase D in RPMI, 400 U/mL of elastase in RPMI, and/or 400 μg/mL of Liberase TM in RPMI.

The whole mouse lung requires at least 1 mL of digestion enzyme: either 2× collagenase D, 400 U/mL of elastase, or 400 μg/m L of Liberase TM.

Place minced cells in an incubator for 30 min at 37°C.

Following incubation, add 100 μL of 100 mM EDTA to inhibit further digestion.

Place cultured cells on ice and homogenize the cell suspension by pipetting repeatedly with a glass Pasteur pipette and rubber bulb. Filter cells through 70 or 100 μm nylon filter (see Note 2) and collect cells into a 5 mL FACS tube. Wash the dish with HBSS complete to collect the remaining cells. Filter the wash into the same FACS tube using the 70 or 100 μm nylon filter.

Centrifuge cells at 300 × g for 5 min at 4°C.

Dump or aspirate supernatant, leaving behind up to 200 μL volume with cells.

3.3. FACS Staining of IMs

Optional: Pulmonary IMs can be enriched via positive selection using anti-CD11b, anti-biotin (for biotinylated anti-Mertk), or anti-CD45 microbeads (25 μL/lung) from Miltenyi Biotec. Follow Miltenyi instructions for optimal enrichment.

Place single-cell suspension on ice.

Make an antibody master mix for FACS staining. Antibody cocktail commonly used: anti-CD206 FITC, anti-CD 11c PECy7, anti-CD11b PB, anti-Ly6C PerCpCy5.5, anti-CD64 APC, anti-MHC II PO, anti-Siglec F PE, anti-B220 APC-Cy7. Stain cells with antibodies for at least 45 min and up to 1.5 h for optimal cell separation during FACS analysis.

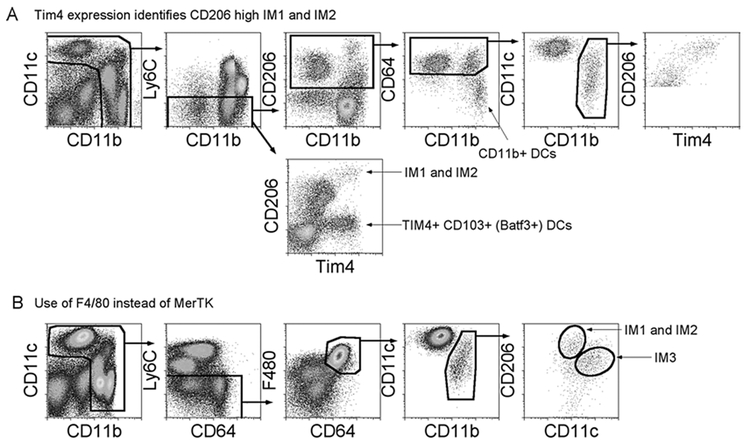

The identification of IMs and the effect of various enzymes on the isolation of IMs in the lung are shown in Fig. 1. In Fig. 1, IMs are first gated as DAPI‒ CD45+ to exclude dead cells and enrich hematopoietic cells. CD45+ cells are then plotted to gate on true cellular size using linear forward, side-scatter parameters. An appropriate cellular size, live gate, is made to exclude subcellular debris. Last double t cells are excluded and plotted as CD11c versus CD11b to gate on myeloid cells. Myeloid cells have high expression of CD11c and CD11b. The myeloid gate is plotted as MerTK versus CD64, since double-positive MerTK and CD64 are macrophage populations. Then, gated Ly6C‒ macrophages are plotted as CD11c versus CD11b to obtain IMs in all enzymatic conditions used (last three rows). Siglec F+ AMs are CD11c+CD11b‒ (AMs appear CD11b+; this is due to autofluorescences). Finally, the IMs are plotted using CD206, CD11c, and MHCII to identify IM1, IM2, and IM3. From our experience, even though the other digestions extract IMs from the lungs, Liberase TM extracts the most quantity of IMs per lung, along with a greater frequency of IM3.

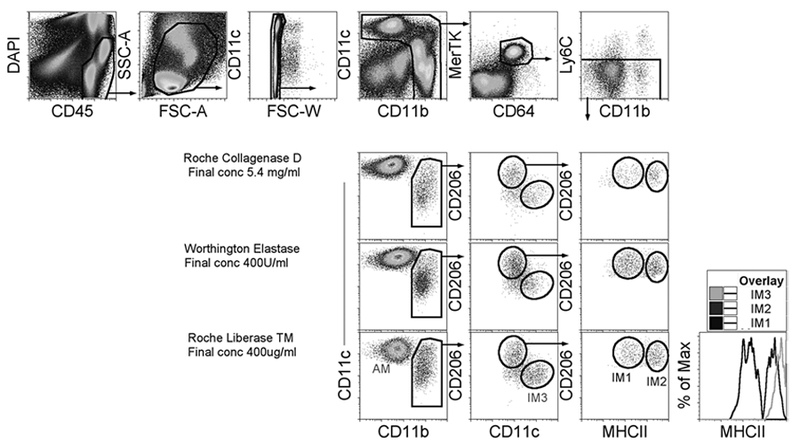

Tim4 expression on two IMs is outlined in Fig. 2a (see Note 3). CD45+ live cells are plotted as CD11c versus CD11b to gate on myeloid cells. Ly6C‒ myeloid cells are then plotted as CD206 versus CD11b to obtain extravascular mononuclear phagocytes. The CD206+ gate contains CD11b+ DCs, AMs, and IMs. The CD206+ gate is then plotted as CD64 versus CD11b to gate on CD64+ macrophages and exclude CD64‒CD11b+ DCs. CD206+CD64+ macrophages are plotted as CD11c versus CD11b. CD11b+ IMs were then plotted as CD206 and Tim4. Tim4+ CD206hl cells contain IM1 and IM2, which can be distinguished by the use of MHCII (Fig. 1). Also, there is another extravascular population in the lung that is Tim4+, Batf3+CD 103+ DCs, which lack CD206 expression and are thus excluded in this IM gating strategy.

The identification of IMs after gating on CD64 and F4/80, instead of MerTK: In Fig. 2b, CD45+ live cells are plotted as CD11c versus CD11b to gate on myeloid cells. Ly6C‒ myeloid cells are then plotted as F480 versus CD64 to obtain macrophages. F480+CD64+ macrophages are plotted as CD11c versus CD11b. CD11b+ IMs are then plotted as CD206 and CD11c to identify the three IMs (Fig. 1).

In conclusion, although, in theory it should not make too much of a difference; the highest quality and most consistent data observed occur when we digest with Liberase TM and initially gate on IMs using MerTK and CD64, as illustrated in Fig. 1 (see Note 4).

Fig. 1.

Identification of pulmonary interstitial macrophages in steady state

Fig. 2.

Alternative gating strategy to identify interstitial macrophages

4. Notes

If an investigator plans to analyze leukocytes beyond the known tissue-resident mononuclear phagocytes (i.e., alveolar macrophages, IMs, and pulmonary DCs) that do not exist in the intravascular space, then the investigator should inject fluorescently conjugated anti-CD45 intravenously 5 min prior to mouse euthanasia to distinguish intravascular versus extravascular leukocytes in the lung. Regardless of extensive perfusion and lung blanching, intravascular leukocytes will be present after lung digest. Therefore, for a definitive extravascular leukocyte count and analysis, intravenous injection of anti-CD45 is highly recommended. Also, to date we have not found a MerTK antibody that can replace the current polyclonal biotinylated antibody used here [5].

Do not use a 40 μm nylon filter or any filter smaller than 70 μm because macrophages may not easily go through a filter that is too fine. Hence, a 40 μm nylon filter may result in reduced recovery of DCs and macrophages for FACS analysis. Furthermore, digested lung cells should always be re-filtered prior to any centrifugation and FACS use.

To obtain the most consistent, high-quality mononuclear phagocyte data, it is best to analyze experiment after isolation and on the same day of digestion. From our experience, the quality of mononuclear phagocyte data significantly decreases with overnight fixation.

To identify IM3 high level of CCR2 expression can be used. However, it is better to use the antibody than the reporter mice, as the reporter CCR2 mice do not display a definitive match with antibody cell surface staining.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: C.V.J. NIH R01 HL115334 and R01 HL135001.

References

- 1.Gibbings SL, Thomas SM, Atif SM et al. (2017) Three unique interstitial macrophages in the murine lung at steady state. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 57:66–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janssen WJ, Barthel L, Muldrow A et al. (2011) Fas determines differential fates of resident and recruited macrophages during resolution of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 184:547–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mould KJ, Barthel L, Mohning MP et al. (2017) Cell origin dictates programming of resident versus recruited macrophages during acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 57:294–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCubbrey AL, Barthel L, Mohning MP et al. (2018) Deletion of c-FLIP from CD11bhi macrophages prevents development of bleomycin- induced lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 58:66–78. 10.1165/rcmb.2017-01540C [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gautier EL, Shay T, Miller J et al. (2012) Gene- expression profiles and transcriptional regulatory pathways that underlie the identity and diversity of mouse tissue macrophages. Nat Immunol 13:1118–1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]