Abstract

Purpose of Review

To determine the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) on clinical and patient-reported outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Recent Findings

We identified randomized clinical trials from inception through April 2018 from MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, CINAHL, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library, and hand searches. After screening 338 references, we included five trials with one post-hoc analysis that evaluated MBIs and collectively included 399 participants. Outcome instruments were heterogeneous across studies. Three studies evaluated RA clinical outcomes by a rheumatologist; one study found improvements in disease activity. A limited meta-analysis found no statistically significant difference in the levels of DAS28-CRP in the two studies that evaluated this metric (− 0.44 (− 0.99, 0.12); I2 0%). Four studies evaluated heterogeneous psychological outcomes, and all found improvements including depressive symptoms, psychological distress, and self-efficacy. A meta-analysis of pain Visual Analog Scale (VAS) levels post intervention from three included studies was not significantly different between MBI participants and control group (− 0.58 (− 1.26, 0.10); I2 0%) although other studies not included in meta-analysis found improvement.

Summary

There are few trials evaluating the effect of MBIs on outcomes in patients with RA. Preliminary findings suggest that MBIs may be a useful strategy to improve psychological distress in those with RA.

Keywords: Mindfulness, Mindfulness-based interventions, Stress, Rheumatoid arthritis, Systematic review

Background

Description of Disease State

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, autoimmune disease affecting approximately 0.5% of the US population and is characterized by joint pain, stiffness, and articular damage [1]. There is an increased prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with RA compared to the general population [2,3]. RA patients with anxiety and/or depression tend to have worse clinical outcomes compared to those without anxiety [4,5].

Description of Intervention

Mindfulness is non-judgmental, present moment awareness [6]. The mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) with the greatest empirical support in chronic illness populations include mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT). These courses are typically led by certified instructors with a mental health background [7,8]. Several other mindfulness-based multi-modal psychotherapies have been developed, and we describe the results of three that have been tested in RA patients: mindful awareness and acceptance therapy (MAAT), the vitality training program (VTP), and internal family systems (IFS).

Proposed Mechanism of Mindfulness

MBIs have been shown to improve mental health including anxiety, depression, and perceived stress [9–11]. There is evidence that MBIs improve psychological well-being via improved cognitive and emotional reactivity [12]. This may be useful for chronic disease states, such as RA, in which the burden of disease-related symptoms and emotional dysregulation may be high [13,14]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Gu et al. used two-stage meta-analytic structural equation modeling (TSSEM) to evaluate various underlying mechanisms of MBIs on psychologic function [12]. There was strong evidence that MBIs improved cognitive and emotional reactivity and moderate evidence for improvements in mindfulness, rumination, and worry.

Reviewing the available data for MBIs in patients with RA is a critical step in determining whether this may be a useful adjunctive strategy for treatment of this chronic inflammatory disease. The objective of this review was to determine if MBIs improve mental and/or physical health domains in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

We included randomized, parallel group-controlled trials. The review was limited to the English language. We reviewed studies performed in adults with RA. There were no any exclusions of study populations based on gender, severity, or duration of RA. The intervention of interest included primary mindfulness interventions including MBSR. Additional multi-modal and primarily psychotherapy-based mindfulness interventions were also included. RA patients participating in MBIs were compared to RA patients not participating in MBIs. This included both active and wait-list control groups.

The primary outcomes of interest were pain, anxiety, depression, self-efficacy, and coping, as well as measures of RA disease activity. Any composite index of psychological wellness and distress was reviewed and synthesized if homogenous.

The following databases were searched on April 19, 2018: Medline (PubMed), Embase, Web of Science, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL, Ebsco), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and PsycINFO (Ebsco). Our search strategy is included in Table 4 (Appendix). The search strategies for each platform were developed separately using controlled vocabulary as well as keywords related to individual concepts. These concepts were combined using appropriate Boolean operators. The concepts of interest included (1) mindfulness, (2) rheumatoid arthritis, and (3) RCT (study design of interest).

Data Collection and Analysis

Studies identified from the above search strategy were screened by two independent reviewers (DD, MCB) for potential relevance using Covidence [15]. At the first stage, studies were reviewed for inclusion based on title and abstract screening. Disputes between reviewers were resolved with discussion. Of the included studies, a full-text review for potential relevance was performed. Disputes between reviewers were resolved with discussion and involvement of a third reviewer (CB). The study selection process was reported in a PRISMA flow diagram [16]. Relevant demographic and outcome data from included studies were evaluated by two independent reviewers (DD, MCP) and included in qualitative synthesis. There was significant heterogeneity among outcomes and only limited quantitative synthesis was possible.

Included studies were assessed on five domains: selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, incomplete outcome data, and reporting bias (Table 5, appendix), adopted from the Cochrane protocol [17]. We constructed risk of bias tables using Revman 5.3.

Psychological outcomes, measures of disease activity, and physical function were reported as continuous variables or in diary format [18,19]. Individual participants were the unit of analysis. We only included randomized, parallel group studies. We attempted to impute data from tables and graphs where possible. We contacted the study authors for clarification, if necessary. Due to the small number of anticipated included studies, we avoided use of funnel plots and assembled findings in table form [20].

We evaluated the effect of MBIs on physical and mental health; factors assessed included individual study methods, patient comorbidities, and study size. We evaluated the body of literature’s strengths and limitations including to what populations and settings the results were generalizable. Finally, we attempted to pool study outcomes for meta-analysis. We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, Q statistic, and tau statistic, generated using Revman 5.3. Significant heterogeneity was considered for I2 statistics greater than 75% and precluded meta-analysis. A random effects model was used to determine statistical heterogeneity.

The strength of evidence for each main outcome was analyzed in accordance with Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group guidelines [21]. GRADEpro GDT software was used for analysis [22]. To address meta-bias, two reviewers screened abstracts, extracted data, and assessed bias independently. Disputes were resolved with reviewer discussion and a third reviewer (CB).

Results

Study Selection and Characteristics

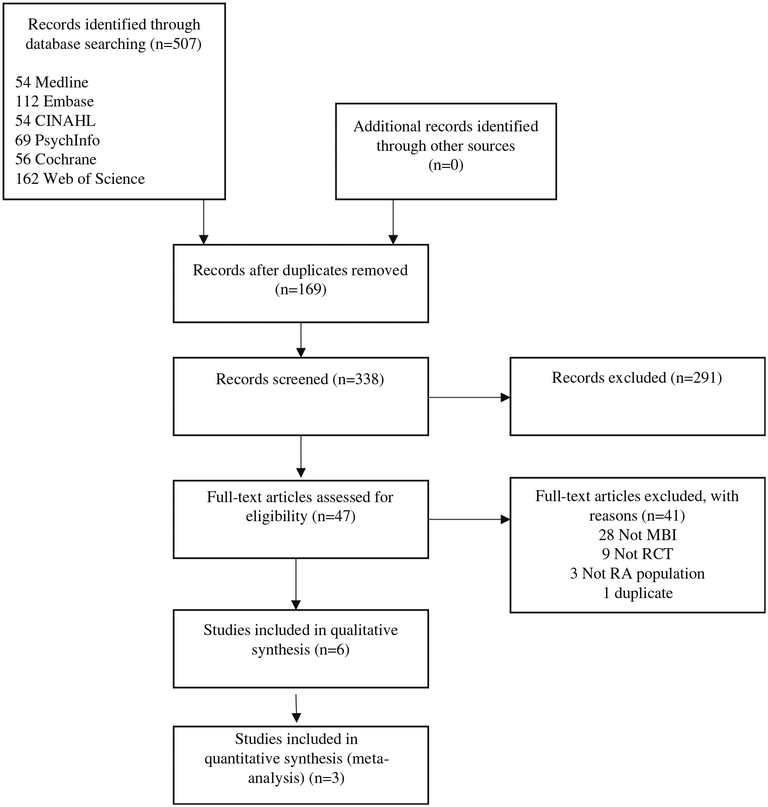

The literature search and cross-reference check produced 507 references, collectively, from Medline (54), Embase (112), CINAHL (54), PsycInfo (69), Cochrane (56), Web of Science (162) (Fig. 1). There were 169 duplicates removed; 338 studies underwent title and abstract screening, of which 291 studies were removed. There were 47 studies assessed for full-text eligibility, and 41 were excluded (28 studies did not evaluate MBIs in RA; 9 studies were not RCTs; 3 studies did not include RA patients; and 1 additional duplicate was noted) (Table 1). There were five studies included in the qualitative synthesis; Davis et al. was a post hoc analysis of the original trial by Zautra et al. [18,19,23–26].

Fig. 1.

Literature search and cross-reference check produced 507 references, collectively, from Medline (54), Embase (112), CINAHL (54), PsycInfo (69), Cochrane (56), Web of Science (162)

Table 1.

Description of mindfulness-based interventions and psychotherapies included in this review

| Mindfulness intervention | Course description |

|---|---|

| Mindfulness-based stress reduction |

A standardized mindfulness program that involves cultivation of non-judgmental attention and awareness and develops a sense of compassion for self and others. Program consists of 7 weekly 2.5-h group classes, full day silent retreat, and encouragement of daily home practice. Both formal and informal relaxation techniques are employed included gentle yoga, body scan, mindful breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery, recognition of pleasant and unpleasant experience, attention to bodily symptoms, and interpersonal communication. MBSR was developed at the University of Massachusetts and is now offered through many university hospital and community-based practices. |

| Mindful awareness and acceptance therapy | Targets affective disturbances through attention to regulation of negative emotional responses to stress and encouragement of positive affective engagement in daily life [19]. The program consists of 8 weekly sessions, like MBSR, but lacking the yoga component and full day retreat. |

| Vitality training program | Addresses the relationship between thoughts, emotions, and somatic experiences in 10, 4.5-h group sessions over 15 weeks. Each session addresses a specific topic related to living with chronic disease including personal resources, values, anger, joy, sorrow, and interacting with others. Creative exercises including writing, music, poetry, and drawing are employed to enhance the learning process. |

| Internal family systems | Teaches patients to attend to and interact with internal experiences mindfully. Mindfulness aspects include noticing and non-judgmental awareness. Program is a combination of biweekly then monthly group meetings over 36 weeks and 15 biweekly individual sessions designed to reinforce concepts and new habits. |

There were two studies that evaluated MBSR, one study that evaluated VTP, one study that evaluated IFS, and one study that evaluated MAAT (Table 2) [18,19,23–26]. The characteristics of these five studies including patient population, intervention, course instructor, and program length are listed in Table 3. All of the studies evaluated patient-reported outcomes; four studies evaluated RA clinical outcomes determined by rheumatologists [18,19,23,24,26] across heterogeneous outcome measures.

Table 2.

Qualitative synthesis: characteristics of included studies

| Study | Year | Population | Sample size | % Male | Age (M (SD)) | Instructors | Intervention | Comparator | Program length/time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pradhan et al. | 2007 | RAa | 63 | 12.7 | C: 56(9) M: 53(11) |

Certified in MBSR | MBSR | Wait-list | 8 weeks# + 3 booster sessions |

| Fogarty et al. | 2015 | RAb | 42 | 12.0 | C: 55(13) M: 52(12) |

Clinical psychologists trained in MBSR, University setting |

MBSR | Wait-list | 8 weeks# |

| Zautra et al. +post hoc analysis by Davis et al. |

2008 | RAa ±recurrent depression (n = 37, +depression) |

144 | 31.9 |

+Depression

M: 46(13) P: 51(11) E: 51(14) -Depression M:57(15) P: 56(13) E: 52(13) |

Clinical psychologists, University Setting |

Mindfulness meditation and emotion regulation therapy (n = 48) |

CBT-P (n = 52) Education (n = 44) |

8 weekly 2-h group sessions |

| Zangi et al. | 2011 | RAb, AS, PSA, other inflammatory arthritis |

71 | 21.1 | C: 55(9) M: 53(9) |

Health professionals trained in VTP |

Vitality training program |

Routine care + CD for home practice |

10 group sessions (4.5 h.) over 15 weeks +booster session at 6 months |

| Shadick et al. | 2013 | RAa | 79 | 10.2 | C: 59(12) M: 58(14) |

IFS trained therapist | Internal family systems |

Education | 6 biweekly group sessions followed by monthly group sessions + 15 biweekly 50-min individual meetings concurrently over 36 weeks |

Physician diagnosed RA

1987 ACR RA Diagnostic Criteria

C control, M MBI, P CBT-P, E Education, AS ankylosing spondylitis, PSA psoriatic arthritis

Table 3.

Outcome measures and results of included studies

| Study | Outcome measures | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|

| Pradhan et al. | SCL-90-R (Depressive Symptoms, General Severity Index), Psychological Weil-Being Scale, Mindfulness Attention Awareness Scale; DAS28-ESR (obtained by rheumatologists). |

No significant between-group differences in disease activity between MBSR and wait-list control at 2 months. Improvements in depressive symptoms, psychologic distress, psychological well-being at 6 months. |

| Fogarty et al. | DAS28-CRP, TJC, SJC (obtained by trained research specialist); PGA, Morning Stiffness; serum CRP. |

MBSR compared to wait-list control showed greater improvements in DAS28-CRP (p = 0.01), morning stiffness (p = 0.03), pain (p = 0.04), TJC (p = 0.02), and PGA (p = 0.02) status post-intervention, and at 4 and 6 months. |

| Zautra et al. + post hoc analysis by Davis et al. |

Clinical Outcomes (only half of the participants, n = 74): TJC, SJC (obtained by 3 rheumatologists); serum 1L-6 Daily diary assessments: Numerical Rating Scales (0–100) Fatigue, Pain; (< 15 min to > 5 h.) Morning Disability; (1—4) Interpersonal Stress; (1—5) Pain-Catastrophizing, Pain Control, Coping Efficacy for Pain; Positive and Negative Affect Scale-Expanded Form (PANAS-X) Serene Affect, Anxious Affect. |

Mindfulness compared to education and CBT-P for RA patients with recurrent depression had significant improvements in negative affect, positive affect, and TJC. Mindfulness showed the greatest improvements in pain, stress reactivity, and pain catastrophizing post intervention compared to CBT-P and education. Post hoc analysis: Mindfulness showed greater improvements in pain-related changes in catastrophizing, morning disability, fatigue, anxious affect, serene affect compared to CBT-P and Education. There were also improvements in disability compared to CBT-P only. Of note, for those with recurrent depression, mindfulness showed greater improvements in fatigue compared to CBT-P and education. |

| Zangi et al. | GHQ-20, Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scale (Pain, Symptoms), Emotion Approach Coping Scale (EAC); Pain, Fatigue, PGA, Self-Care Ability, Overall Weil-Being all per numeric rating scales (0–10). |

Significant treatment effects favoring VTP were found post-intervention and at 12 months for psychological distress (GHQ-20), self-efficacy (pain, symptoms), emotional processing (EAC), fatigue, self-care, overall-well-being. No differences in Pain VAS were noted between groups. |

| Shadick et al. | RA Disease Activity Index Joint Score (RADAI), SF-12 Physical Function, Pain VAS, Beck Depression Inventory, State Trait Anxiety Inventory; DAS28-CRP (obtained by rheumatologists). |

Significant improvements in pain (treatment effect, - 14.9 (29.1 SD); p = 0.04) and physical function (14.6 (25.3); p = 0.04) favoring 1FS compared to education were found post-intervention; improvements in self-reported joint pain (−0.6 (1.10;/? = 0.04), self-compassion (1.8 (2.8);p = 0.01), and depressive-symptoms (− 3.2 (5.0); p = 0.01) were sustained at 1 year. There were not any improvements in DAS28-CRP at 9- and 21-month follow-up; improvements in the RADAI were noted at 9 months (− 0.9 (− 1.6 to −0.2); p = 0.01). |

TJC tender joint count, SJC swollen joint count, PGA patient global assessment, DAS-28 Disease Activity Score-28 joints, CRP C-reactive protein, GHQ-20 General Health Questionairre-20, SF-12 Short-Form-12, MBSR mindfulness-based stress reduction, CBT-P cognitive behavioral therapy-pain, VTP vitality training program

Trials were based in the USA [18,19,23,26], England [25], Norway [25], and New Zealand [24]. Study participants had RA based on physician diagnosis; two studies required participants to meet the 1987 American College of Rheumatology Diagnostic Criteria [24,25]. Participants were mostly female and 50–60 years of age. Studies were conducted at university hospital-associated clinics by psychologists or certified healthcare professionals. The study by Zautra et al. with post hoc analysis by Davis et al. analyzed RA patients based on a history of recurrent depression.

Intervention Characteristics

An MBSR course is a standardized program developed at the University of Massachusetts Medical School and consists of a two and a half hour introductory session, seven weekly two and a half hour active sessions, and a 4-h silent retreat [27]. Sessions consist of a variety of mindfulness activities such as guided imagery, body scan, mindful eating, and gentle yoga (Table 2). Pradhan et al. and Fogarty et al. were the only identified RCTs that employed the traditional MBSR program as the study intervention [23,24]. There were no identified RCTs in an RA population that used MBCT as the study intervention.

Other multi-modal MBIs include VTP, IFS, and MAAT. VTP is a group therapy that focuses on specific topics related to living with chronic disease and includes creative exercises and as well as music, drawing, and poetry. IFS is longer in duration (36 weeks) than the other MBIs and incorporates both group therapy and individual sessions. IFS does not include moving meditations such as yoga or walking. MAAT includes shorter meditation components than traditional MBSR or MBCT methods without a day-long retreat or yoga.

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction

Pradhan et al. studied the clinical and psychological outcomes after completion of an MBSR course with three booster sessions over the course of 4 months [23]. Participants were enrolled in a traditional MBSR program composed of seven weekly 2.5-h sessions and one full-day retreat; mindfulness practice at home for 45 min per day, 6 days per week, was encouraged. The MBSR course was compared to a usual care, wait-list control group that was offered the program for free after conclusion of the wait-list period. The MBSR program was run by clinical psychologists trained in MBSR. Clinical outcomes (TJC, SJC) were performed by two rheumatologists masked to treatment status. Patients continued to receive their RA prescription medication throughout the study.

Fogarty et al. evaluated clinical RA outcomes after a traditional MBSR course without booster sessions [24]. Courses conducted at a university-hospital setting led by a clinical psychologist trained in MBSR. Clinical outcomes were assessed by a masked research assistant. The MBSR course was compared to a usual care, wait-list control group who was offered the course free of charge after the wait-list period.

Vitality Training Program

Zangi et al. evaluated PROs after completion of a 10-session mindfulness-based group program with booster session at 6 months [25]. The VTP was compared to a usual care group who was given CDs for voluntary mindfulness practice without formal instruction. The VTP program was administered by trained healthcare professionals (social workers, nurses, physical therapists, occupational therapists) and outcomes were assessed via anonymous questionnaires mailed to participants as well as telephone interviews conducted by researchers blinded to the treatment group.

Mindfulness Meditation and Emotional Regulation Therapy/Mindful Awareness and Acceptance Therapy

Zautra et al. evaluated clinical and psychological outcomes after completion of a mindfulness-based program consisting of eight weekly 2-h sessions and administered by clinical psychologists and post-doctoral students in a university hospital setting [19]. The MBI was originally referred to as mindfulness meditation and emotional regulation therapy [19] and later referred to as mindful awareness and acceptance therapy (MAAT) [18]. The mindfulness program was compared to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for pain and an educational control. Outcomes were obtained via diary measures, organized by blinded research assistants; half of the participants from each group were randomized to receive laboratory and clinical assessments by a rheumatologist (unclear if blinded). Davis et al. later analyzed the diary assessments, including a sub-group analysis for those with recurrent depression, focusing on fatigue, pain catastrophizing, morning disability, interpersonal stress, pain-related cognitions, serene affect, and anxious affect.

Internal Family Systems

Shadick et al. evaluated psychological outcomes and RA clinical outcomes after completion of the psychotherapeutic program conducted by a trained IFS specialist [26]. The IFS program consisted of both individual and group sessions that was 9 months in duration. Clinical outcomes were collected by rheumatologists masked to the treatment group. The IFS program was compared to an RA education group that served as a minimal attention control group.

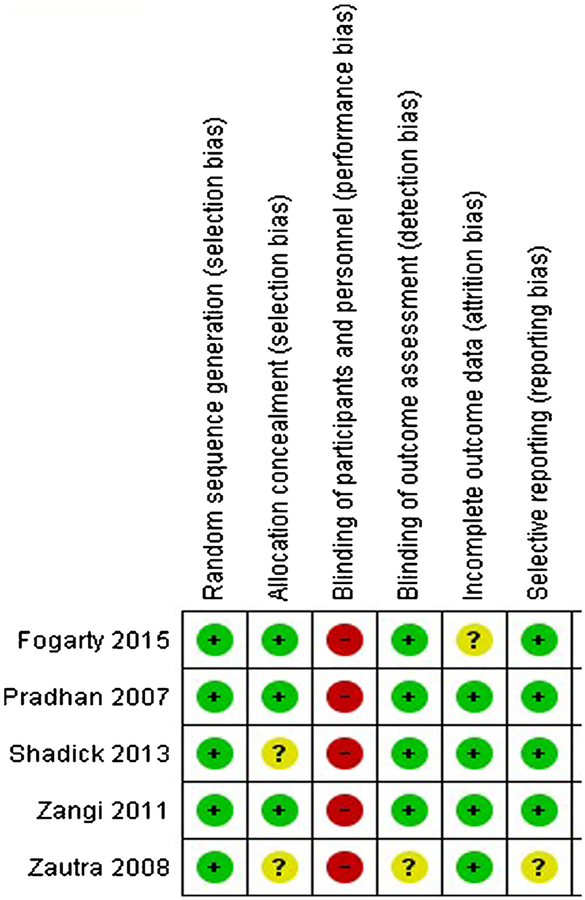

Overall, there was serious bias attributed to all included studies (Fig. 2). It was not possible to blind participants to the intervention, introducing a risk of bias for known treatment allocation. However, Zautra et al. argued that participants were not made aware of other treatment groups [19]. Limited methodologies were reported in the brief letter to the editor by Fogarty et al. with the exception of masking of the outcome assessor [24]. Fogarty et al. later clarified to the study authors that the MBSR program was conducted by a clinical psychologist trained in MBSR. There was an unclear level of performance bias in the study by Zautra et al. with unclear masking of outcome assessors.

Fig. 2.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Outcomes

Patient-reported and clinical outcomes were variable across studies (Table 3). Depressive symptoms, evaluated in three studies [18,19,23,26], were significantly improved post-intervention. Zautra et al. grouped participants based on a history of recurrent depression, noting greater improvements in daily fatigue (numeric rating scale, 0–100) for those with recurrent depression compared to CBT or education [19]. Psychologic distress (SCL-90R:General Severity Index, GHQ-20) and anxiety (PANAS-X: Anxious Affect, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory) were improved for MBI participants compared to controls in three studies [18,23,25] with one study reporting no difference [26]. After participation in the VTP, self-efficacy and emotional processing (Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scale, Emotion Approach Coping Scale) were improved in RA participants [25].

There were three studies that evaluated the DAS28 composite RA disease activity index with mixed findings [23,24,26]. Pain VAS was evaluated in three studies with discrepancies in improvement [24–26]; daily pain scores (diary method) and pain catastrophizing were found to be improved in one study [18,19].

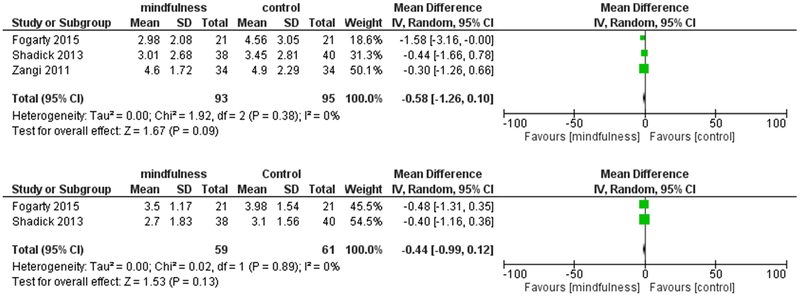

Reported outcomes across MBIs were very heterogeneous and only limited meta-analysis was possible. PROs assessed in at least two studies included the patient global assessment of disease activity (PGA), pain level based on a numeric rating scale, and DAS28-CRP. The PGA was analyzed by Fogarty et al. [24] and Zangi et al. [25] The PGA was found to be significantly reduced post-intervention in the VTP study and unchanged in the MBSR study; however, the I2 statistic was 83%, representing significant statistical heterogeneity, and this outcome was excluded from meta-analyses. Pain according to a numeric rating scale was evaluated by Fogarty et al. [24], Zangi et al. [25], Shadick et al. [26], and Davis et al. [18] evaluated daily pain via diary methods which was unlike the single-score, post-intervention ratings reported by the two included studies [18,19]. Using a random effects model for assessment of statistical heterogeneity, no significant difference in pain VAS level was found immediately post-MBI (MBSR, VTP, IFS) (Fig. 3). The quality of evidence was determined to be low according to GRADE criteria (risk of bias, directness, consistency, and precision). There was serious risk of bias (unblinded studies), and pain VAS scores were extracted across three different MBIs which affected the quality of evidence.

Fig. 3.

a, b Random effects model for assessment of statistical heterogeneity

Finally, the DAS28 composite index was obtained in three studies, although different inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP)) were used, thus limiting meta-analysis [23,24,26]. Pradhan et al. included the ESR as the inflammatory marker for this composite index while Fogarty et al. and Shadick et al. included the CRP [23,24,26]. There was low-quality evidence that there was not a statistically significant difference in DAS28-CRP levels post-intervention (− 0.44 (− 0.99 to 0.12); I2 = 0%) (Fig. 3). According to the GRADE criteria, there was serious indirectness for the comparison in which the IFS program is a psychotherapy that includes individual and group sessions, incorporating mindfulness elements, while MBSR is a traditional, group-based MBI.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review to evaluate MBIs for patients with RA. There were six articles describing five RCTs examining the effect of traditional MBIs (MBSR) and multi-modal and psychotherapeutic mindfulness-based interventions (MAAT, VTP, IFS) compared to wait-list, attention-control groups, and CBT. There were only two studies that evaluated the traditional MBSR program in RA patients versus a wait-list control group. Fogarty et al. only focused on RA clinical outcomes and reported limited results in their published letter to the editor; Pradhan et al. evaluated both psychological and RA clinical outcomes [23,24]. Fogarty supplied unpublished group data for the purpose of meta-analysis when requested by the study authors. Future studies evaluating the effect of MBSR in RA patients should ideally match the control group for attention and time to limit control group bias.

Due to the heterogeneity of interventions (MBSR, VTP, IFS), outcome measures (Table 3), and limited availability of results, only limited meta-analyses were possible. A meta-analysis of pain VAS scores collected post-intervention by Fogarty et al. (MBSR), Shadick et al. (IFS), and Zangi et al. (VTP) did not find any significant differences in levels. We felt that the averaged-daily dairy method by Zautra et al. was not similar enough to the post-intervention pain score to be included in meta-analysis. Validated and standardized outcome measurement instruments should be implemented in future studies evaluating MBIs.

Yoga was an important aspect of the MBIs that was not well described. Only Pradhan et al. explicitly stated that yoga was part of the intervention. Fogarty et al. later clarified that gentle yoga was incorporated into their program. Gentle yoga is an essential component of the MBSR program and an important tool for learning mindfulness [27]. Yoga has previously been shown to improve physical and psychological outcomes in adults with RA [28,29]. MBIs that contain a yoga component must be carefully reviewed and tailored for patients with RA to avoid injury [30]. For RA patient with physical limitations, a yoga practice in the MBI may be discouraging if not appropriately tailored to this patient population.

Based on limited evidence, this review suggests that MBIs and other multi-modal approaches may be effective for improving patient-reported outcomes and emotional disturbances related to RA. One included study evaluated RA patients with and without recurrent depression and found significant improvements in pain (including catastrophizing), tender joint count, fatigue, negative and positive affect, and stress reactivity [19]. Improvement in the subjective components of RA disease activity, including the patient global assessment and tender joint count, was found in three studies [19,24,26]. As described above, there was significant statistical heterogeneity for the PGA (I2 83%), and this outcome was not included in meta-analysis; there was incomplete group level data to perform a meta-analysis for the tender joint count. Improvements in the subjective components of disease activity may have been mediated through improvements in emotional reactivity, coping, and self-efficacy [12,31–33]. Future work exploring the effect of MBIs for RA patients, especially with comorbid anxiety and depression, is required to determine whether this may be a useful adjunctive strategy for RA management.

Conclusion

There is limited, low-quality evidence available in the literature on MBIs for adjunctive treatment of RA. The included studies suggest benefit in psychological outcomes for RA participants enrolled in a MBI compared to control (CBT, education, wait-list). There are inconclusive findings regarding the effect of MBIs on RA disease activity and pain.

Acknowledgments

Funding Dr. DiRenzo is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32AR048522. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix

Table 4.

Search Strategy

| PubMed | |

|---|---|

| #1 | (“mindfulness”[mesh] OR “Meditation”[Mesh] OR “Relaxation Therapy”[Mesh] OR “Relaxation”[Mesh] OR mindful* [tiab] OR savoring[tiab] or vipassana[tiab] or zen[tiab] or meditat* [tiab] or relax* [tiab] OR mbsr[tiab] OR mbct[tiab] OR mantra[tiab]) |

| #2 | (“rheumatoid arthritis”[tiab] OR “Arthritis, Rheumatoid”[Mesh] OR “inflammatory arthritis”[tiab]) |

| #3 | ((randomized controlled trial[pt] OR controlled clinical trial[pt] OR randomized[tiab] OR placebo[tiab] OR clinical trials as topic[mesh:noexp] OR randomly[tiab] OR trial[ti]) NOT (Animal[mesh] NOT human[mesh])) |

| #4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 |

| Embase | |

| #1 | (‘mindfulness’/exp. OR ‘mindfulness based cognitive therapy’/exp. OR ‘mindfulness based stress reduction’/exp. OR ‘meditation’/exp) OR (mindful* OR savoring or vipassana or zen or meditat* or relax* OR mbsr OR mbct OR mantra):ti,ab |

| #2 | ‘rheumatoid arthritis’/exp. OR ‘rheumatoid arthritis’:ti,ab OR ‘inflammatory arthritis’:ti,ab |

| #3 | (Animals/exp. or invertebrate/exp. or ‘animal experiment’/exp. or ‘animal tissue’/exp. or ‘animal cell’/exp. or nonhuman/exp) NOT (humans/exp) |

| #4 | #1 AND #2 |

| #5 | #4 NOT #3 |

| #6 | ‘crossover procedure’:de OR ‘double-blind procedure’:de OR ‘randomized controlled trial’:de OR ‘single-blind procedure’:de OR (random* OR factorial* OR crossover* OR cross NEXT/1 over* OR placebo* OR doubl* NEAR/1 blind* OR singl* NEAR/1 blind* OR assign* OR allocat* OR volunteer*):de,ab,ti |

| #7 | #5 AND #6 |

| Psyclnfo | |

| #1 | (DE “Mindfulness” OR DE “Meditation” OR mindful* OR savoring or vipassana or zen or meditat* or relax* OR mbsr OR mbct OR mantra) |

| #2 | (“rheumatoid arthritis” OR DE “Rheumatoid Arthritis” OR “inflammatory arthritis”) |

| CINAHL | |

| #1 | (MH “Mindfulness”) OR (MH “Meditation (Iowa NIC)”) OR (MH “Meditation”) OR mindful* OR savoring or vipassana or zen or meditat* or relax* OR mbsr OR mbct OR mantra |

| #2 | (“rheumatoid arthritis” OR MH “Arthritis, Rheumatoid+” OR “inflammatory arthritis”) |

| #3 | (TX allocat* random*) OR (MH “Quantitative Studies”) OR (MH “Placebos”) OR (TX placebo*) OR (TX random* allocat*) OR (MH “Random Assignment”) OR (TX randomi* control* trial*) OR (TX ((singl* n1 blind*) or (singl* n1 mask*))) OR (TX ((doubl* n1 blind*) or (doubl* n1 mask*))) OR (TX ((tripl* n1 blind*) or (tripl* n1 mask*))) OR (TX ((trebl* n1 blind*) or (trebl* n1 mask*))) OR (TX clinic* n1 trial*) OR (PT Clinical trial) OR (MH “Clinical Trials+”) |

| Web of Science: | |

| z#1 | TS = (mindful* OR savoring or vipassana or zen or meditat* or relax* OR mbsr OR mbct OR mantra) |

| #2 | TS = (“rheumatoid arthritis” OR “inflammatory arthritis”) |

| #3 | TS = (“randomized controlled trial*” OR “controlled clinical trial*” OR randomized OR randomised OR “single blind” OR “double blind” OR placebo OR “controlled trial*” OR “clinical trial*” OR randomly) OR Tl = (trial) |

| #4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 |

| Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trial | |

| #1 | mindful* or savoring or vipassana or zen or meditat* or relax* or mbsr or mbct or mantra:ti,ab,kw |

| #2 | MeSH descriptor: [Mindfulness] explode all trees |

| #3 | MeSH descriptor: [Meditation] explode all trees |

| #4 | MeSH descriptor: [Relaxation Therapy] explode all trees |

| #5 | MeSH descriptor: [Relaxation] explode all trees |

| #6 | #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 |

| #7 | MeSH descriptor: [Arthritis, Rheumatoid] explode all trees |

| #8 | (“rheumatoid arthritis” or “inflammatory arthritis”):ti,ab,kw |

| #9 | #7 or #8 |

| #10 | #9 and #6 |

Table 5.

Risk of bias criteria

| Type of bias | Criteria | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | Unclear | |

| Selection bias: random sequence Generation |

Random-numbers table or a computer software program |

Tossing a coin, throwing dice or basing randomization on a date, name, etc. |

Methods not described |

| Selection bias: allocation concealment |

Concealment of allocation means strict implementation of a randomized sequence without foreknowledge of the next assignment. Strategies that include central randomization by computer or phone and sequentially numbered envelopes that are both sealed and opaque are low risk. |

Strategies with a reasonable chance of being anticipated. |

Inadequate description of the envelope process, which is often the case, should be marked as “unclear risk of bias.” |

| Performance bias |

If methods to mask participants and physicians were described and these methods had a reasonable chance of being effective. |

If treatment assignment known by patient/physician. |

If the study did not discuss methods of masking the participant or physician. |

| Detection bias | Methods to mask the outcome assessor were described. | The outcome assessor was not-masked. |

Methods to mask the outcome assessor were not described. |

| Incomplete outcome data/attrition bias |

Losses to follow-up are similar in number and in reason between intervention and control. An intention to treat analysis is performed. |

Losses to follow-up are more than 10% different between the intervention and control groups. |

If attrition is not reported or reasons for loss of attrition are not reported. |

| Reporting bias | If the primary outcome(s) in the methods section is identical to those reported in the results section of the manuscript. If a protocol is available, we will also review for discrepancies between targeted outcomes and results. |

If the primary outcomes differ between the methods section or protocol and manuscript. |

If there is no reported primary outcome in a trial registry, the outcome will be considered “unclear.” |

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The protocol for this systematic review was registered at Prospero.org: 2018 CRD42018094717 (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/).

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors

References

- 1.Hunter TM, Boytsov NN, Zhang X, Schroeder K, Michaud K, Araujo AB. Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in the United States adult population in healthcare claims databases, 2004–2014. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37(9):1551–7. 10.1007/s00296-017-3726-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Isik A, Koca SS, Ozturk A, Mermi O. Anxiety and depression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26(6): 872–8. 10.1007/s10067-006-0407-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.VanDyke MM, Parker JC, Smarr KL, et al. Anxiety in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51(3):408–12. 10.1002/art.20474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matcham F, Norton S, Scott DL, Steer S, Hotopf M. Symptoms of depression and anxiety predict treatment response and long-term physical health outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis: secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Rheumatology. 2016;55(2): 268–78. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boer AC, Huizinga TWJ, van der Helm-van Mil AHM. Depression and anxiety associate with less remission after 1 year in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2018:annrheumdis-2017–212867. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(4):822–48. 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goyal M, Singh S, Sibinga EMS, Gould NF, Rowland-Seymour A, Sharma R, et al. Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(3):357–68. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma M, Rush SE. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction as a Stress Management Intervention for Healthy Individuals: A Systematic Review. doi: 10.1177/2156587214543143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marchand WR. Mindfulness meditation practices as adjunctive treatments for psychiatric disorders. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2013;36(1):141–52. 10.1016/j.psc.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strauss C, Cavanagh K, Oliver A, Pettman D. Mindfulness-based interventions for people diagnosed with a current episode of an anxiety or depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials Laks J, ed. PLoS One 2014;9(4):e96110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mccubbin T, Dimidjian S, Kempe K, Glassey MS, Ross C, Beck A. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in an integrated care delivery system: one-year impacts on patient-centered outcomes and health care utilization. Perm J. 2014;18(4):4–9. 10.7812/TPP/14-014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gu J, Strauss C, Bond R, Cavanagh K. How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;37:1–12. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marks R Self-efficacy and arthritis disability: an updated synthesis of the evidence base and its relevance to optimal patient care. Heal Psychol open. 2014;1(1):2055102914564582 10.1177/2055102914564582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barsky AJ, Ahern DK, Orav EJ, Nestoriuc Y, Liang MH, Berman IT, et al. A randomized trial of three psychosocial treatments for the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;40(3):222–32. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Innovation VH. Covidence Systematic Review Software. www.covidence.org.

- 16.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group TP. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928 10.1136/BMJ.D5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis MC, Zautra AJ, Wolf LD, Tennen H, Yeung EW. Mindfulness and Cognitive-behavioral Interventions for Chronic Pain: Differential Effects on Daily Pain Reactivity and Stress Reactivity. doi: 10.1037/a0038200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zautra AJ, Davis MC, Reich JW, Nicassario P, Tennen H, Finan P, et al. Comparison of cognitive behavioral and mindfulness meditation interventions on adaptation to rheumatoid arthritis for patients with and without history of recurrent depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(3):408–21. 10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lau J, Ioannidis JPA, Terrin N, Schmid CH, Olkin I. The case of the misleading funnel plot. BMJ. 2006;333(7568):597–600. 10.1136/bmj.333.7568.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman AE. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. guidelinedevelopment.org/handbook. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McMaster University, (developed by Evidence Prime I. GRADEpro GDT: GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool. 2015. gradepro.org.

- 23.Pradhan EK, Baumgarten M, Langenberg P, Handwerger B, Gilpin AK, Magyari T, et al. Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(7):1134–42. 10.1002/art.23010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fogarty FA, Booth RJ, Gamble GD, Dalbeth N, Consedine NS. The effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction on disease activity in people with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(2):472–4. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zangi HA, Mowinckel P, Finset A, Eriksson LR, Høystad TØ, Lunde AK, et al. A mindfulness-based group intervention to reduce psychological distress and fatigue in patients with inflammatory rheumatic joint diseases: a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(6):911–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shadick NA, Sowell NF, Frits ML, Hoffman SM, Hartz SA, Booth FD, et al. A randomized controlled trial of an internal family systems-based psychotherapeutic intervention on outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis: a proof-of-concept study. J Rheumatol. 2013;40(11):1831–41. 10.3899/jrheum.121465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kabat-Zinn J Full catastrophe living : using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York: Bantam Books trade paperback; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moonaz SH, Bingham CO, Wissow L, Bartlett SJ. Yoga in sedentary adults with arthritis: effects of a randomized controlled pragmatic trial. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(7):1194–202. 10.3899/jrheum.141129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greysen HM, Greysen SR, Lee KA, Hong OS, Katz P, Leutwyler H. A qualitative study exploring community yoga practice in adults with rheumatoid arthritis. J Altern Complement Med. 2017;23(6): 487–93. 10.1089/acm.2016.0156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cramer H, Ward L, Saper R, Fishbein D, Dobos G, Lauche R. The safety of yoga: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;182(4):281–93. 10.1093/aje/kwv071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hofmann SG, Gómez AF. Mindfulness-based interventions for anxiety and depression. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2017;40(4):739–49. 10.1016/j.psc.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Desrosiers A, Vine V, Klemanski DH, Nolen-Hoeksema S. MINDFULNESS AND EMOTION REGULATION IN DEPRESSION AND ANXIETY: COMMON AND DISTINCT MECHANISMS OF ACTION. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30(7):654–61. 10.1002/da.22124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freudenthaler L, Turba JD, Tran US. Emotion regulation mediates the associations of mindfulness on symptoms of depression and anxiety in the general population. Mindfulness (N Y). 2017;8(5): 1339–44. 10.1007/s12671-017-0709-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]