Abstract

Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome (WHS) is caused by partial deletion of the short arm of chromosome 4 and is characterized by dysmorphic facies, congenital heart defects, intellectual/developmental disability, and increased risk for congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH). In this report, we describe a stillborn girl with WHS and a large CDH. A literature review revealed 15 cases of WHS with CDH, which overlap a 2.3-Mb CDH critical region. We applied a machine-learning algorithm that integrates large-scale genomic knowledge to genes within the 4p16.3 CDH critical region and identified FGFRL1 , CTBP1 , NSD2 , FGFR3 , CPLX1 , MAEA , CTBP1-AS2 , and ZNF141 as genes whose haploinsufficiency may contribute to the development of CDH.

Keywords: Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, machine-learning algorithm

Introduction

Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome (WHS; OMIM 194190) is a contiguous gene deletion syndrome involving a group of genes physically clustered in the short arm of chromosome 4. This clinically recognizable syndrome was described independently by Drs. Ulrich Wolf and Kurt Hirschhorn, and has a minimum birth incidence of 1 in 95,896 and infant mortality rate of 17%. 1 2 3 WHS is characterized by a constellation of dysmorphic facial features, including a “Greek warrior helmet” appearance caused by a combination of a broad, flat nasal bridge and a high forehead, hypertelorism, abnormally formed ears with preauricular tags and pits, a short philtrum, micrognathia, and microcephaly. Individuals with WHS typically have pre- and postnatal growth retardation, developmental delay, hypotonia, variable intellectual disability, and, often, seizures. 4 Several structural birth defects are also commonly observed in individuals with WHS, including central nervous system anomalies (33%), cleft lip and/or cleft palate (25–50%), eye defects (25–50%), congenital heart defects (50%), scoliosis and kyphosis (60–70%), and genitourinary tract anomalies (25%). 4 A small subset of individuals with WHS also have congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH). 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

The WHS critical region has been defined as a 1.5- to1.6-Mb region on chromosome 4p16.3 encompassing a region between ∼0.4 and 1.9 Mb from the 4p terminus that includes LETM1 , SLBP , NSD2 (previously known as WHSC1 ), and NELFA (previously known as WHSC2 ). 17 19 20 21 However, it remains unclear whether deletion of this region is sufficient to cause CDH and which genes on 4p16.3 potentially contribute to the development of the diaphragm. Here, we present a novel case of CDH associated with WHS, review the literature to define a CDH critical region on chromosome 4p16.3, and use a machine-learning algorithm that integrates large-scale genomic knowledge sources to identify candidate genes within the WHS CDH critical region that may contribute to the development of CDH.

Case Report

Our patient was a stillborn girl who was delivered vaginally after induction of labor for gestational hypertension and polyhydramnios at 36 6/7 weeks of gestation. This was the first pregnancy of this nonconsanguineous couple, but the mother had a history of two prior first trimester miscarriages. Pregnancy was complicated by advanced maternal age of 38 years and advanced paternal age of 43 years as well as maternal obesity. MaterniT21 cell-free DNA screening did not reveal increased risk for genetic abnormalities. At 32 weeks of gestation, ultrasound examinations revealed intrauterine growth restriction with an estimated fetal weight of 1,235 g, (<3rd percentile), polyhydramnios with an amniotic fluid index of 30+, bilateral cleft lip and palate, a large left-sided CDH with herniation of the stomach, multiple bowel loops, and 20% of the liver, and dextroposition of the heart secondary to the CDH. At delivery, the fetus demonstrated no signs of life and was pronounced stillborn. Fetal autopsy including imaging with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and an external visual evaluation confirmed the in utero findings. The confinement of the herniated organs and their separation from pleural fluid suggested that the CDH was covered by a membranous sac.

A chromosome analysis performed on amniocytes at Baylor Genetics revealed a 46,XX,del(4)(p15.3) chromosomal complement. A chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA Version 8.3.1) revealed a de novo ∼18.9-Mb deletion of the distal end of chromosome 4p (minimal deletion chr4:85,743–18,953,893; maximal deletion chr4:1–18,984,868; hg19) consistent with a molecular diagnosis of WHS. A gain on chromosome 15q13.1q13.2 (minimum gain chr15:29,213,743–30,300,265; maximum gain chr15:28,525,505–30,349,558; hg19) involving four genes— APBA2 , FAM189A1 , NSMCE3 , and TJP1 —was also identified. This gain is located between recurrent breakpoint 3a (BP3A) and recurrent breakpoint 4 (BP4) and was inherited from the asymptomatic father. None of the genes involved are known to play a role in the development of CDH.

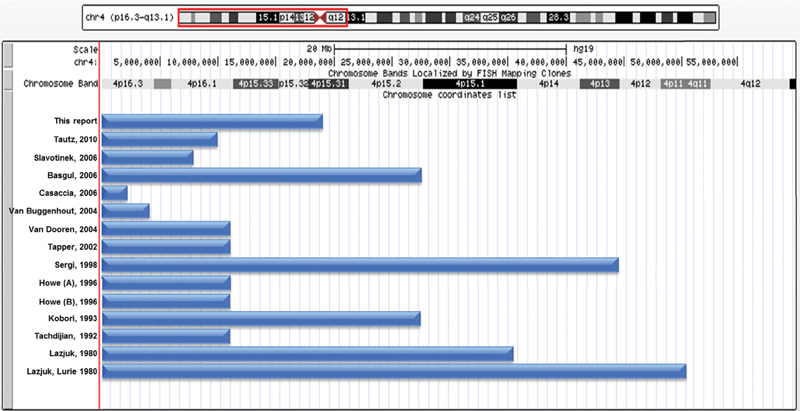

A review of the literature revealed 15 other cases of CDH associated with WHS. Clinical and cytogenetic/molecular data for these individuals are summarized in Table 1 and Fig. 1 , respectively. In all cases, the phenotypes of these individuals were consistent with those previously seen in individuals with WHS. The cytogenetic and molecularly defined deletions in these cases overlap an ∼2.3-Mb deletion carried by an individual described by Casaccia et al. 15 This CDH critical region contains 47 RefSeq genes.

Table 1. Clinical and molecular data from individuals with WHS and CDH. Individual cases are listed based on the year of their publication. Data presented includes phenotypic information, CDH type, and underlying genetic defects with method of analysis other than karyotype, if applicable. Only cases with phenotype information and/or genetic details are included. CDH and WHS cases not present in the table include Pober et al (2005) with a described deletion at 4p16 without inclusion of further phenotypic or genetic information.

| Report | Sex | Clinical features | Deletion (hg19) | Genetic origin/size/analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| This report | F; stillbirth at 36-wk gestation | –Dysmorphic facial features, bilateral cleft lip and palate –Incomplete ossification of C3 and C4 vertebral bodies, dysgenesis of the corpus callosum –Left-sided saccular CDH containing 20% liver |

Minimum:chr4:85,743–18,953,893 Maximum: chr4:1–18,984,868 |

De novo, ∼19 Mb Chromosomal microarray |

| Tautz et al (2010) | F; alive | –Dysmorphic facial features –Right-sided double-outlet right ventricle of the Fallot type, with a pulmonary artery stenosis, ventricular septal defect, and a persistent ductus arteriosus –Hypoplasia of the corpus callosum and immature gyration –Left-sided CDH |

chr4:1–9,945,373 | De novo, ∼9.9 Mb SNP array, FISH |

| Slavotinek et al (2006) | M | –Left-sided CDH | Minimum:chr4:1–6,762,449 Maximum: chr4:1–7,978,364 |

De novo, ∼8 Mb FISH, array comparative genomic hybridization |

| Basgul et al (2006) | F; terminated at 27-wk gestation | –Dysmorphic facial features, scaphoid abdomen –Fetal hypotonia on ultrasound, cystic dilation of nuchal area –Left-sided CDH |

46,XX, del(4)(p15.2) | De novo |

| Casaccia et al (2006) | F; alive | –Dysmorphic facial features, cleft soft palate –Mildly retarded psychomotor development appreciated with age –Left-sided CDH |

chr4:1–2,336,628 (FISH) | De novo, ∼2.3 Mb FISH |

| Van Buggenhout et al (2004) | F; alive | –Cleft palate –Pulmonary stenosis –Impaired growth parameters appreciated at age 1 –Left-sided CDH |

Minimum:chr4:1–3,679,582 Maximum:chr4:1–4,119,652 |

Unspecified, ∼4.1 Mb FISH, comparative genomic hybridization |

| van Dooren et al(2004) | M; alive | –Unilateral cleft palate, right-sided ear tag –Mildepispadias –Severe epilepsy at 1 year of life –Left-sided CDH |

46,XY.ish del(4)(p16.1) | De novo FISH |

| Tapper et al (2002) | F; terminated in utero | –Bilateral cleft lip, clubbed feet –Increased nuchal translucency, cystic hygroma, cervical hemivertebrae, lumbar meningomyelocele –Ventricular septal defect –Left-sided CDH |

46,XX,der(4)t(4;13)(p16;q32).ish der(4)t(4;13) (p16;q32)(WHS–) | Paternal unbalanced segregation of t(4;13)(p16;q32) FISH |

| Sergi et al (1998) | F; deceased following birth at 31-wk gestation | –Dysmorphic facial features, microcephaly, bilateral cleft palate –Multiple renal cortical cysts –Left-sided CDH |

46,XX,del(4)(p13) | De novo |

| Howe et al (1996) | M; deceased following birth | –Ventricular septal defect, transposition of the great vessels, dilated third cerebral ventricle –CDH, unspecified side |

46,XYdel(4)(p16) | De novo |

| F; stillbirth | –Dandy–Walker malformation, facial cleft –CDH, unspecified side |

46,XXdel(4)(p16) | De novo | |

| Kobori et al (1993) | M; deceased following birth at 27-wk gestation | –Dysmorphic facial features, bilateral cleft lip, unilateral cleft palate, clubbed foot –Undescended testicles, hypospadias, horseshoe kidney –Truncus arteriosis –CDH, unspecified side |

46,XY,rec(4)dup(4q)inv(4)(p15.2q25) | Meiotic recombinant chromosome derived from paternal 46,XY,inv(4)(p15.2q25) |

| Tachdjian et al (1992) | M; terminated at 37-wk gestation | –Dysmorphic facial features, cleft palate –Major hypospadias, anteposed anus –Left-sided CDH |

46,XYdel(4)(p16) | De novo |

| Lazjuk et al (1980) | F; stillborn at 35-wk gestation | –Dysmorphic facial features, exophthalmos, coloboma of the right iris –Dislocation of the hips and bilateral club feet –Left-sided CDH |

Not obtained, sibling with 46,XY,del(4)(p15) | Maternal balanced translocation 46,XX,t(4;22)(p15.2;p11) |

| Lurie et al (1980) | F; deceased following birth | –Dysmorphic facial features, hard palate cleft –Bilateral club feet, hypotonia –Left-sided CDH |

46,XX,4p- | Unspecified |

Abbreviations: SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization.

Fig. 1 Gene mapping of chromosome deletions in individuals with WHS and CDH reveals a ∼2.3-Mb CDH critical region.

The maximum deletions identified in individuals with WHS and CDH are represented by blue bars mapped using the UCSC Genome Browser (GRCh37/hg19). The order of their presentation is the same as in Table 1 . All deletions overlap an ∼2.3-Mb deletion carried by an individual described by Casaccia et al 15 This CDH critical region contains 47 RefSeq genes.

To identify genes in the critical region that may contribute to the development of CDH, we adapted a machine-learning approach that had previously been developed to identify candidate genes with regard to pathogenicity in epilepsy. 22 The core function of the algorithm is to integrate large-scale genomic knowledge to develop a phenotype-specific pathogenicity score to predict which genes may predispose to a specified phenotype. Detailed methods and validation of the approach can be found in the original manuscript. 22 A description of how we applied this approach to identify CDH-related genes is described below.

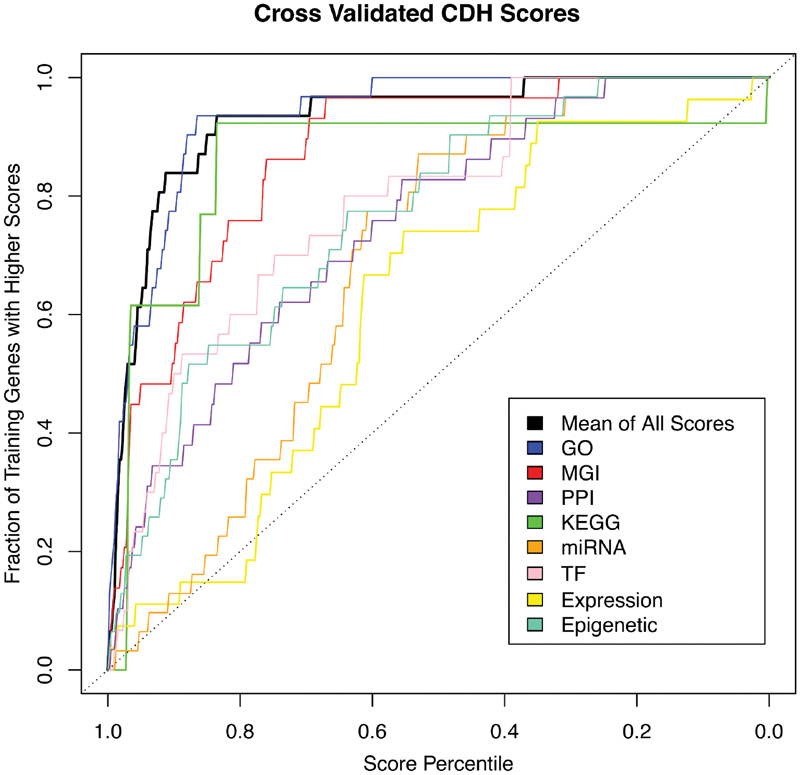

Briefly, 31 training genes known to be associated with CDH and diaphragm development in humans and/or mice ( CHAT , DNASE2 , EFEMP2 , EFNB1 , FBN1 , FGFRL1 , FREM1 , FZD2 , GATA4 , GLI2 , GLI3 , HLX , HOXB4 , LOX , LRP2 , MET , MSC , NIPBL , NR2F2 , PAX3 , PBX1 , PDGFRA , RARA , RARB , ROBO1 , SLIT3 , SOX7 , STRA6 , TCF21 , WT1 , and ZFPM2 ) were manually curated based on a review of the literature and data obtained from the Mouse Genome Informatics database ( http://www.informatics.jax.org/ ). 23 We determined training patterns for these CDH genes based on data from each of the following knowledge sources: Gene Ontology (GO), 24 Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI) phenotype annotation, 23 protein–protein integration networks, 25 the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomics (KEGG) molecular interaction network data, 26 micro RNA (miRNA) targeting, 27 GeneAtlas expression distribution, 28 transcription factor binding, and epigenetic histone modifications. 29 We then compared the patterns of all RefSeq genes to the CDH-specific pattern in each knowledge area and calculated an omnibus score for each RefSeq gene. Leave-one-out cross-validation revealed that our scoring approach identified the CDH training genes more efficiently than random chance ( Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2 Leave-one-out cross-validation demonstrates that our machine-learning algorithm is able to identify CDH training genes more efficiently than random chance.

. Each of the 31 CDH-associated training genes was removed from the set and genome-wide pathogenicity scores were recalculated. The colored lines represent the efficiency of each knowledge source to score the training gene when left out. The bold black line represents the mean of all other scores. Each of the knowledge sources, as well as the omnibus score, identified the CDH training genes better than random chance.

In reviews authored by Donahoe et al and Kardon et al, we identified 35 CDH-related genes/CDH candidates that were not among the genes selected for use in the training set. 30 31 As an additional test of the algorithm, we determined the percentiles of these genes compared with all RefSeq genes based on their omnibus scores ( Supplemental Table S1 , available in online version only). The median percentile of these genes was 95.5 ( Supplemental Fig. S1 , available in online version only). All but one gene had percentiles > 50. DSEL , which had a percentile of 47, is considered a candidate gene for CDH based on its disruption by a maternally inherited 2.7-Mb deletion of 18q22.1 that was identified in a patient with a late-presenting, right-sided diaphragmatic hernia and microphthalmia and a p.Met14Ile variant identified in an unrelated individual with a late-presenting, anterior diaphragmatic hernia. 32 Overall, this analysis provides additional evidence that the algorithm is able to detect CDH-related/CDH candidate genes more efficiently than random chance.

Having tested the machine-learning algorithm, we then prioritized the RefSeq genes within the CDH critical region of approximately 2.3 Mb based on the omnibus scores generated by the algorithm. The top eight genes identified— FGFR3 , FGFRL1 , CTBP1-AS2 , NSD2 , ZNF141 , MAEA , CPLX1 , and CTBP1 —are described in Table 2 . All of these genes had omnibus scores whose percentile was > 85 when compared with all RefSeq genes and all genes within the CDH critical region.

Table 2. Descriptions of top CDH candidate genes located in the CDH critical region on 4p16 as selected by the machine-learning algorithm. Genes from the CDH critical region on 4p16 whose omnibus percentile scores were >85 when compared with all RefSeq genes and all genes within the CDH critical region. Genes are ranked by omnibus score. Data presented includes known or postulated function including human disease associations, mouse phenotype, gene location, and ExAC pLI score.

| Gene | Omnibus score percentile (RefSeq/CDH critical region) | Function/human disease associations | Knockout mouse phenotypes | Location (hg19) | pLIscore |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

FGFR3

(OMIM no. 134934) |

99.9/100 | –Cell determination and proliferation, wound healing, angiogenesis, embryo development, ossification –Achondroplasia (OMIM no. 100800), hypochondroplasia (OMIM no. 146000), crouzonodermoskeletal syndrome (OMIM no. 612247) |

–Abnormal chondrocytes, decreased bone mineral density

50

–Abnormal long bone morphology and structure 51 56 |

chr4:1,793,299–1,808,872 | 0 |

| FGFRL1 (OMIM no. 605830) | 98.9/97.9 |

–Not fully understood, postulated to act as a decoy receptor that can bind and sequester fibroblast growth factor ligands and may be involved in cell–cell adhesion

39

40

–WHS (OMIM no. 194190) |

–Cranial abnormalities, diaphragmatic hernia, abnormal kidney development, neonatal lethality

36

–Abnormal vascular development, VSD, abnormal cranial morphology, anemia, abnormal diaphragm development, abnormal skeletal morphology 35 |

chr4:1,011,822–1,026,898 | 0.58 |

| CTBP1-AS2 ( C4orf42 ) | 98/95.7 | –Unknown | None available | chr4:1,249,300–1,288,291 | NA |

| NSD2 ( WHSC1 ; OMIM no. 602952) | 97.3/93.6 | –Expressed ubiquitously in early development, histone methylation –WHS (OMIM no. 194190) |

–ASD, VSD, cleft palate, abnormal sternum ossification 47 | chr4: 1,871424–1,982,207 | 1 |

| ZNF141 (OMIM no. 194648) | 97/91.5 |

–Limb development, possibly transcriptional regulation

55

–Postaxial polydactyly type A6 (OMIM no. 615226) |

None available | chr4: 337,814 -384–864 | 0.16 |

| MAEA (OMIM no. 606801) | 91/89.4 | –Erythroblast attachment to macrophages, erythroblast maturation | –Increased NK T cell number, abnormal coat appearance (International Knockout Mouse Consortium, mousephenotype.org) | chr4: 1,289,851–1,340,147 | 0.84 |

| CPLX1 (OMIM no. 605032) | 89/87.2 | –Synaptic vesicle exocytosis –WHS (OMIM no. 194190) |

–Seizures, abnormal hearing, abnormal neuron physiology 52 | chr4:784,957–826,198 | 0.8 |

| CTBP1 (OMIM no. 602618) | 85.6/85.1 |

–Cell–cell adhesion and apoptosis, tumor suppression, neurodevelopment, and myogenesis and vascularization

45

–WHS (OMIM no. 194190) |

–Small size and increased mortality 37 | chr4:1,211,448–1,249,953 | 0.98 |

Abbreviations: OMIM, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man phenotype number; pLI, probability of loss-of-function intolerance in the ExAC database ( http://exac.broadinstitute.org/ ).

Using exome sequencing, we screened a previously described cohort of 68 individuals with CDH for rare (<1% allele frequency), putatively deleterious sequence changes in the seven protein-coding genes in this list, as previously described. 33 This cohort consists of 39 males and 29 females—29 European Americans, 25 Hispanics, 5 African Americans, 1 Asian, 1 Asian Indian, 1 Filipino, 1 Middle Easterner, 1 European American/Hispanic, and 4 individuals of undeclared ancestry. 33 None of the individuals in this cohort are known to be related and the molecular cause of their CDH has not been determined. All of the rare, putatively deleterious sequence changes identified in FGFR2 , FGFRL1 , NSD2 , and ZNF141 were missense changes ( Table 3 ). In all cases in which parental samples were available, these sequence variants were inherited from a parent without CDH and most have been previously described in the ExAC database ( http://exac.broadinstitute.org/ ) or in gnomAD ( http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/ ). 34 No rare, putatively deleterious sequence changes were identified in MAEA , CPLX1 , or CTBP1 .

Table 3. Rare, putatively deleterious sequencing changes in CDH candidate genes identified in a cohort of 48 individuals with CDH. We screened a cohort of 48 individuals with CDH for rare, putatively deleterious sequencing changes in the top sevenprotein-coding genes identified by the machine-learning algorithm— FGFR3 , FGFRL1 , NSD2 , ZNF141 , MAEA , CPLX1 , and CTBP1 . For each gene, patient identifier information including ethnicity and sex, change in transcript, mode of inheritance, in silicopredictions, ExAC/gnomAD information, and clinical description are provided. No rare, putatively deleterious sequence changes were identified in MAEA , CPLX1 , or CTBP1 .

| Gene | Identifier, ethnicity, sex | Change [transcript] | Inheritance | In silico predictions | ExAC/gnomAD | Clinical description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FGFR3 | TX73, Filipino male | c.985G > A p.Val329Ile [NM_000142.4] |

Maternal | CADD = 16.9 SIFT = damaging PolyPhen-2 = probably damaging MT = disease causing |

0 homo, 13 het in 120,218 alleles; 0 homo, 29 het in 276,896 alleles |

Left-sided CDH, after repair developed a paraesophageal hernia, sister died of CDH |

| FGFRL1 | TX51, Middle Eastern male | c.1474G > A p.Val492Met [NM_001004356] |

Unknown | CADD = 21.5 SIFT = tolerated PolyPhen-2 = benign MT = disease causing |

22 homo, 532 het in 26,252 alleles; 50 homo, 1,459 het in 193,304 alleles |

Agenesis of the left diaphragm, consanguinity due to conception with donor egg from father's family, triplet gestation, PFO, PDA, left pulmonary artery hypoplasia, inguinal hernia, dysmorphic features |

| FGFRL1 | TX57, Asian Indian female |

c.1474G > A p.Val492Met [NM_001004356] |

Paternal | CADD = 21.5 SIFT = tolerated PolyPhen-2 = benign MT = disease causing |

22 homo,532 het in 26,252 alleles; 50 homo, 1,459 het in 193,304 alleles |

Agenesis of the left diaphragm, PDA, ASD |

| NSD2 | TX12, Northern European male | c.904C > T p.Pro302Ser [NM_133330] |

Maternal | CADD = 14.4 SIFT = tolerated PolyPhen-2 = benign MT = disease causing |

0 homo, 18 het in 120,646 alleles; 0 homo, 40 het in 275,674 alleles |

Left-sided CDH |

| NSD2 | TX13, European male | c.2807T > C p.Val936Ala [NM_133330] |

Paternal | CADD = 21.2 SIFT = tolerated PolyPhen-2 = benign MT = disease causing |

Not found Not found |

Left-sided sac CDH, right-sided eventration |

| NSD2 | TX80, Northern European male | c.229G > A p.Asp77Asn [NM_133330] |

Maternal | CADD = 24.3 SIFT = damaging PolyPhen-2 = benign MT = disease causing |

0 homo, 12 het in 121,272 alleles; 0 homo, 17 het in 276,304 alleles |

Left-sided posterolateral CDH, ASD |

| ZNF141 | TX28, African American female | c.487C > T p.Arg163Cys [NM_003441] |

Unknown | CADD = 26.5 SIFT = damaging PolyPhen-2 = possibly damaging MT = disease causing |

1 homo, 217 het in 121,106 alleles; 1 homo, 456 het in 276,920 alleles |

Agenesis of the left diaphragm, large VSD |

| ZNF141 | TX29, Northern European male | c.487C > T p.Arg163Cys [NM_003441] |

Unknown | CADD = 26.5 SIFT = damaging PolyPhen2 = possibly damaging MT = disease causing |

1 homo, 217 het in 121,106 alleles; 1 homo, 456 het in 276,920 alleles |

Right-sided sac CDH |

Abbreviations: ASD, atrial septal defect; CADD, Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion; EEG, electroencephalogram; MT, MutationTaster; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PolyPhen-2, HumVar predictions reported; SIFT, Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant.

Discussion

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia is a rare but recurrently identified feature of WHS. Our patient is the first identified case of diaphragmatic hernia with a sac in association with WHS. It is likely, possibly through a haploinsufficiency model, that one or more genes mapping to the ∼2.3-Mb CDH critical region on chromosome 4p16 are sufficient to cause CDH. Using a machine-learning algorithm, we identified FGFR3 , FGFRL1 , CTBP-AS2 , NSD2 , ZNF141 , MAEA , CPLX1 , and CTBP1 as genes in this region that may contribute to the development of CDH ( Table 2 ).

FGFRL1 , CTBP1 , and NSD2 have been previously suggested as CDH candidate genes. In mouse embryos, Fgfrl1 , Ctbp1 , and Nsd2 transcripts have been detected in the pleuroperitoneal folds (PPF) at E11.5 and E12.5 as well as the developing diaphragm at E16.5. 16 35 36 37 38

FGFRL1 is thought to act as a decoy receptor that can bind and sequester fibroblast growth factor ligands and may be involved in cell–cell adhesion. 39 40 Initial studies by Trueb and Taeschler showed that FGFRL1 expression increased during development, particularly within the diaphragm. 41 Two independently generated knockout models confirmed the importance of FGFRL1 in the diaphragm as these mice displayed abnormally muscularized diaphragms that resulted in lung hypoinflation and death shortly after birth. 35 36 These descriptions did not identify any abnormalities in innervation or in myofiber types, although a more recent paper indicates that loss of FGFRL1 leads to a decrease in slow muscle fibers during late embryological development secondary to apoptosis. 42 In addition, the expression of Fgfrl1 is decreased in the nitrofen CDH model of Bochdalek-type CDH. 43 Decreased levels of FGFRL1 during late gestation could contribute to abnormal diaphragm muscularization and eventual hernia formation. Although these studies clearly establish a role for FGFRL1 in diaphragm development, none have indicated that haploinsufficiency of FGFRL1 is sufficient to cause diaphragmatic hernia in humans. 44

CTBP1 is a transcriptional coregulator identified as a component in complexes containing DNA-binding transcription factors that are involved in many different biological pathways such as cell–cell adhesion, apoptosis, tumor suppression, neurodevelopment, myogenesis, and vascularization. 45 Loss of Ctbp1 in a mouse knockout model resulted in mice that were 30% smaller at birth and was associated with 23% mortality rate by postnatal day 20 due to unspecified causes. Interestingly, loss of CTBP1 and CTBP2 in Ctbp1 −/− ; Ctbp2 +/− mice resulted in embryonic lethality and defective myofiber formation in the diaphragm. 37

NSD2 encodes a histone methyltransferase that is ubiquitously expressed during early development. 46 47 48 NSD2 functions together with developmental transcription factors to repress abnormal transcription. NSD2 -deficient mice demonstrate WHS-related phenotypes including growth deficiencies, craniofacial defects, and cardiac abnormalities. 47 In addition, NSD2 has been associated with various forms of cancer and may contribute to development of cancer in WHS patients. 46 47 48 49 Although there were no diaphragm abnormalities appreciated in NSD2 -deficient mice, NSD2 's function as a transcriptional regulator during early development makes it a strong candidate.

FGFR3 , CPLX1 , MAEA , CTBP1-AS2 , and ZNF141 have not been previously suggested as possible CDH candidate genes. Although Fgfr3 , Cplx1 , and Maea are expressed in the PPF at E11.5 and E12.5 and in the developing mouse diaphragm at E16.5, diaphragmatic defects have not been documented in FGFR3-, CPLX1-, and MAEA-deficient mice. 38 50 51 52 53 CTBP1-AS2 is a noncoding RNA gene located in a head-to-head configuration with CTBP1. ZNF141 encodes a zinc finger–containing protein ubiquitously expressed at a low level in all tissues tested. 54 Postaxial polydactyly in a consanguineous Pakistani family has been attributed to a homozygous c.1420C > T, p.Thr474Ile variant in ZNF141 . 55 Mouse models of ZNF141deficiency have not been generated. Phenotypes associated with the aforementioned genes such as achondroplasia for FGFR3 and polydactyly for ZNF141 were not reported in any of the 15 cases of CDH in WHS. However, some patients did display limb or skeletal defects, including club foot and incomplete ossification of cervical vertebrae.

In all cases where parental samples were available, the rare, putatively deleterious sequence changes identified in FGFR3 , FGFRL1 , NSD2 , ZNF141 , MAEA , CPLX1 , and CTBP1 in a cohort of 68 individuals with CDH were found to be inherited from an unaffected parent. In all but one case, these changes were also documented among control individuals in the ExAC database or in gnomAD ( Table 3 ). While we cannot rule out the possibility that these changes may confer some level of increased risk for the development of CDH, it is unlikely that they are sufficient to cause CDH in isolation.

In leave-one-out cross-validation studies, we have shown that the machine-learning algorithm used to identify FGFR3 , FGFRL1 , CTBP1-AS2 , NSD2 , ZNF141 , MAEA , CPLX1 , and CTBP1 as candidate genes in the WHS CDH critical region is able to identify CDH training genes more efficiently than random chance. We also demonstrated that the algorithm was able to detect 35 CDH-related/CDH candidate genes not included in the training list more efficiently than random chance. This suggests that this machine-learning algorithm could be used in future studies to prioritize CDH candidate genes in other CDH critical regions. It is also possible that this algorithm could be used to prioritize putatively deleterious changes found in individuals with CDH for further analysis based on the likelihood that the gene(s) they affect are CDH-related.

One strength of this machine-learning algorithm is its ability to incorporate data from a wide variety of knowledge sources. 22 At the same time, its reliance on previously generated data stored in these sources is one of its limitations. This reliance may bias predictions against CDH genes whose mode of action is unlike those of previously reported CDH genes. A similar bias can also be introduced by the choice of the training genes. We also note that the scores generated for each gene are only as effective as the a priori knowledge for that gene. If little or no information is known about a gene, or if a gene is not annotated in the RefSeq, the algorithm will not be able to accurately calculate a score.

In conclusion, CDH associated with WHS can be attributed to haploinsufficiency of one or more genes located in the ∼2.3-Mb critical region on chromosome 4p16.3. Using a machine-learning algorithm trained using a set of CDH-associated genes, we identified FGFRL1 , CTBP1 , NSD2 , FGFR3 , CPLX1 , MAEA , C TBP1-AS2 , and ZNF141 as genes whose haploinsufficiency may contribute to the development of CDH.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient and her family for allowing us to present this interesting case.

Funding Statement

Funding This project was supported by the National Institutes of Health/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD064667 to DAS), National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke (F30 NS083159 to IMC), the United States National Human Genome Research Institute/National Heart Blood and Lung Institute (UM1 HG006542 to the Baylor-Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics), the National Human Genome Research Institute (K08 HG008986 to JEP), and the Ting Tsung and Wei Fong Chao Foundation (Physician-Scientist Award to JEP).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Wolf U, Reinwein H, Porsch R, Schröter R, Baitsch H. Deficiency on the short arms of a chromosome No. 4 [in German] Humangenetik. 1965;1(05):397–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper H, Hirschhorn K. Apparent deletion of short arms of one chromosome (4 or 5) in a child with defects of midline fusion. Mamm Chrom Nwsl. 1961;4(14):14–16. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirschhorn K, Cooper H L, Firschein I L. Deletion of short arms of chromosome 4-5 in a child with defects of midline fusion. Humangenetik. 1965;1(05):479–482. doi: 10.1007/BF00279124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Battaglia A, Carey J C, South S T. Seattle,WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 2015. Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lazjuk G I, Lurie I W, Ostrowskaja T I et al. The Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome. II. Pathologic anatomy. Clin Genet. 1980;18(01):6–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1980.tb01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lurie I W, Lazjuk G I, Ussova Y I, Presman E B, Gurevich D B. The Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome. I. Genetics. Clin Genet. 1980;17(06):375–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1980.tb00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tachdjian G, Fondacci C, Tapia S, Huten Y, Blot P, Nessmann C. The Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome in fetuses. Clin Genet. 1992;42(06):281–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1992.tb03257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kobori J, Seto-Donlon S, Gregory T, Bangs D, Hsieh C. A case of monosomy 4p and trisomy 4q derived from a meiotic recombination. Am J Hum Genet Suppl. 1993;55:1578. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howe D T, Kilby M D, Sirry H et al. Structural chromosome anomalies in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Prenat Diagn. 1996;16(11):1003–1009. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0223(199611)16:11<1003::AID-PD995>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sergi C, Schulze B R, Hager H D et al. Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome: case report and review of the chromosomal aberrations associated with diaphragmatic defects. Pathologica. 1998;90(03):285–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tapper J K, Zhang S, Harirah H M et al. Prenatal diagnosis of a fetus with unbalanced translocation (4;13)(p16;q32) with overlapping features of Patau and Wolf-Hirschhorn syndromes. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2002;17(06):347–351. doi: 10.1159/000065383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Dooren M F, Brooks A S, Hoogeboom A JM et al. Early diagnosis of Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome triggered by a life-threatening event: congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;127A(02):194–196. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pober B R, Lin A, Russell M et al. Infants with Bochdalek diaphragmatic hernia: sibling precurrence and monozygotic twin discordance in a hospital-based malformation surveillance program. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;138A(02):81–88. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basgul A, Kavak Z N, Akman I, Basgul A, Gokaslan H, Elcioglu N. Prenatal diagnosis of Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome (4p-) in association with congenital diaphragmatic hernia, cystic hygroma and IUGR. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2006;33(02):105–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casaccia G, Mobili L, Braguglia A, Santoro F, Bagolan P. Distal 4p microdeletion in a case of Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2006;76(03):210–213. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tautz J, Veenma D, Eussen B et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia and a complex heart defect in association with Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A(11):2891–2894. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Buggenhout G, Melotte C, Dutta B et al. Mild Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome: micro-array CGH analysis of atypical 4p16.3 deletions enables refinement of the genotype-phenotype map. J Med Genet. 2004;41(09):691–698. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.016865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slavotinek A M, Moshrefi A, Davis R et al. Array comparative genomic hybridization in patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia: mapping of four CDH-critical regions and sequencing of candidate genes at 15q26.1-15q26.2. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14(09):999–1008. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.South S T, Bleyl S B, Carey J C. Two unique patients with novel microdeletions in 4p16.3 that exclude the WHS critical regions: implications for critical region designation. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A(18):2137–2142. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hammond P, Hannes F, Suttie M et al. Fine-grained facial phenotype-genotype analysis in Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20(01):33–40. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Battaglia A, Carey J C, South S T. Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome: A review and update. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2015;169(03):216–223. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell I M, Rao M, Arredondo S D et al. Fusion of large-scale genomic knowledge and frequency data computationally prioritizes variants in epilepsy. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(09):e1003797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blake J A, Bult C J, Kadin J A, Richardson J E, Eppig J T; Mouse Genome Database Group.The Mouse Genome Database (MGD): premier model organism resource for mammalian genomics and genetics Nucleic Acids Res 201139(Database issue):D842–D848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ashburner M, Ball C A, Blake J A et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet. 2000;25(01):25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cowley M J, Pinese M, Kassahn K Set al. PINA v2.0: mining interactome modules Nucleic Acids Res 201240(Database issue):D862–D865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Hirakawa M.KEGG for representation and analysis of molecular networks involving diseases and drugs Nucleic Acids Res 201038(Database issue):D355–D360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis B P, Burge C B, Bartel D P. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120(01):15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su A I, Wiltshire T, Batalov S et al. A gene atlas of the mouse and human protein-encoding transcriptomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(16):6062–6067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400782101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernstein B E, Stamatoyannopoulos J A, Costello J F et al. The NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Mapping Consortium. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(10):1045–1048. doi: 10.1038/nbt1010-1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donahoe P K, Longoni M, High F A. Polygenic causes of congenital diaphragmatic hernia produce common lung pathologies. Am J Pathol. 2016;186(10):2532–2543. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kardon G, Ackerman K G, McCulley D J et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernias: from genes to mechanisms to therapies. Dis Model Mech. 2017;10(08):955–970. doi: 10.1242/dmm.028365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zayed H, Chao R, Moshrefi A et al. A maternally inherited chromosome 18q22.1 deletion in a male with late-presenting diaphragmatic hernia and microphthalmia-evaluation of DSEL as a candidate gene for the diaphragmatic defect. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A(04):916–923. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beck T F, Campeau P M, Jhangiani S N et al. FBN1 contributing to familial congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167A(04):831–836. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lek M, Karczewski K J, Minikel E Vet al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans Nature 2016536(7616):285–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Catela C, Bilbao-Cortes D, Slonimsky E, Kratsios P, Rosenthal N, Te Welscher P.Multiple congenital malformations of Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome are recapitulated in Fgfrl1 null mice Dis Model Mech 20092(5–6):283–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baertschi S, Zhuang L, Trueb B. Mice with a targeted disruption of the Fgfrl1 gene die at birth due to alterations in the diaphragm. FEBS J. 2007;274(23):6241–6253. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hildebrand J D, Soriano P. Overlapping and unique roles for C-terminal binding protein 1 (CtBP1) and CtBP2 during mouse development. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(15):5296–5307. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.15.5296-5307.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russell M K, Longoni M, Wells J et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia candidate genes derived from embryonic transcriptomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(08):2978–2983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121621109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trueb B, Zhuang L, Taeschler S, Wiedemann M. Characterization of FGFRL1, a novel fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor preferentially expressed in skeletal tissues. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(36):33857–33865. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300281200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rieckmann T, Kotevic I, Trueb B. The cell surface receptor FGFRL1 forms constitutive dimers that promote cell adhesion. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314(05):1071–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trueb B, Taeschler S. Expression of FGFRL1, a novel fibroblast growth factor receptor, during embryonic development. Int J Mol Med. 2006;17(04):617–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amann R, Wyder S, Slavotinek A M, Trueb B. The FgfrL1 receptor is required for development of slow muscle fibers. Dev Biol. 2014;394(02):228–241. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dingemann J, Doi T, Ruttenstock E M, Puri P. Downregulation of FGFRL1 contributes to the development of the diaphragmatic defect in the nitrofen model of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2011;21(01):46–49. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1262853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lopez J imenez N, Gerber S, Popovici V et al. Examination of FGFRL1 as a candidate gene for diaphragmatic defects at chromosome 4p16.3 shows that Fgfrl1 null mice have reduced expression of Tpm3, sarcomere genes and Lrtm1 in the diaphragm. Hum Genet. 2010;127(03):325–336. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0777-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stankiewicz T R, Gray J J, Winter A N, Linseman D A. C-terminal binding proteins: central players in development and disease. Biomol Concepts. 2014;5(06):489–511. doi: 10.1515/bmc-2014-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stec I, Wright T J, van Ommen G J et al. WHSC1, a 90 kb SET domain-containing gene, expressed in early development and homologous to a Drosophila dysmorphy gene maps in the Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome critical region and is fused to IgH in t(4;14) multiple myeloma. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7(07):1071–1082. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.7.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nimura K, Ura K, Shiratori Het al. A histone H3 lysine 36 trimethyltransferase links Nkx2-5 to Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome Nature 2009460(7252):287–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vougiouklakis T, Hamamoto R, Nakamura Y, Saloura V. The NSD family of protein methyltransferases in human cancer. Epigenomics. 2015;7(05):863–874. doi: 10.2217/epi.15.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ozcan A, Acer H, Ciraci S et al. Neuroblastoma in a child with Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2017;39(04):e224–e226. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Su N, Xu X, Li C et al. Generation of Fgfr3 conditional knockout mice. Int J Biol Sci. 2010;6(04):327–332. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.6.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Colvin J S, Bohne B A, Harding G W, McEwen D G, Ornitz D M. Skeletal overgrowth and deafness in mice lacking fibroblast growth factor receptor 3. Nat Genet. 1996;12(04):390–397. doi: 10.1038/ng0496-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reim K, Mansour M, Varoqueaux F et al. Complexins regulate a late step in Ca2+-dependent neurotransmitter release. Cell. 2001;104(01):71–81. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00192-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Soni S, Bala S, Gwynn B, Sahr K E, Peters L L, Hanspal M. Absence of erythroblast macrophage protein (Emp) leads to failure of erythroblast nuclear extrusion. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(29):20181–20189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603226200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tommerup N, Aagaard L, Lund C L et al. A zinc-finger gene ZNF141 mapping at 4p16.3/D4S90 is a candidate gene for the Wolf-Hirschhorn (4p-) syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2(10):1571–1575. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.10.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kalsoom U E, Klopocki E, Wasif N et al. Whole exome sequencing identified a novel zinc-finger gene ZNF141 associated with autosomal recessive postaxial polydactyly type A. J Med Genet. 2013;50(01):47–53. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eswarakumar V P, Schlessinger J. Skeletal overgrowth is mediated by deficiency in a specific isoform of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(10):3937–3942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700012104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.