Abstract

Background:

Elevated clot strength (maximum amplitude [MA]) measured by thrombelastography (TEG) is associated with thrombotic complications. However, it remains unclear how MA translates to thrombotic risks, as this measurement is independent of time, blood flow, and clot degradation. We hypothesize that under flow conditions, increased clot strength correlates to time-dependent measurements of coagulation and resistance to fibrinolysis.

Materials and methods:

Surgical patients at high risk of thrombotic complications were analyzed with TEG and total thrombus-formation analysis system (T-TAS). TEG hypercoagulability was defined as an r <10.2 min, angle >59, MA >66 or LY30 <0.2% (based off of healthy control data, n = 141). The T-TAS AR and PL chips were used to measure clotting at arterial shear rates. T-TAS measurements include occlusion start time, occlusion time (OT), occlusion speed (OSp), and total clot generation (area under the curve). These measurements were correlated to TEG indices (R time, angle, MA, and LY30). Both T-TAS and TEG assays were challenged with tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) to assess clot resistance to fibrinolysis.

Results:

Thirty subjects were analyzed, including five controls. TEG-defined hypercoagulability by MA was detectedin52% of the inflammatory bowel disease/cancer patients; 0%was detected in the controls. There were no TEG measurements that significantly correlated with T-TAS AR and PL chip. However, in the presence of t-PA, T-TAS AR determined OSp to have an inverse relationship with TEG angle (−0.477, P = 0.012) and LY30 (−0.449, P = 0.019), and a positive correlation with R time (0.441 P = 0.021). In hypercoagulability determined by TEG MA, T-TAS PL had a significantly reduced OT (4:07 versus 6:27 min, P = 0.043). In hypercoagulability defined by TEG LY30, T-TAS PL had discordant findings, with a significantly prolonged OT (6:36 versus 4:30 min, P = 0.044) and a slower OSp (10.5 versus 19.0 kPa/min, P = 0.030).

Conclusions:

Microfluidic coagulation assessment with T-TAS has an overall poor correlation with most TEG measurements in a predominantly hypercoagulable patient population, except in the presence of t-PA. The one anticipated finding was an elevated MA having a shorter time to platelet-mediated microfluidic occlusion, supporting the role of platelets and hypercoagulability. However, hypercoagulability defined by LY30 had opposing results in which a low LY30 was associated with a longer PL time to occlusion and slower OSp. These discordant findings warrant ongoing investigation into the relationship between clot strength and fibrinolysis under different flow conditions.

Keywords: Thrombelastography, TEG, T-TAS, Microfluidics, Hypercoagulable, Platelet

Introduction

In-hospital thrombotic complications are common in both medical and surgical patients. Although prophylactic subcutaneous heparin can reduce the risk of deep vein thrombosis,1 higher risk patients may receive an additional benefit by adding an antiplatelet medication.2 Despite these recommendations, screening patients for hypercoagulability has not become a standard of care to direct targeted therapies. This is partially attributable to conventional labs that assess coagulation lacking an ability to detect hypercoagulability. However, whole blood viscoelastic hemostatic assays (VHA) has been shown to predict thrombotic complications in trauma patients,3,4 liver disease patients,5 cardiac surgery patients,6 inflammatory bowel disease patients,7 and malignancy.5,8 This is further supported by patients presenting with new onset deep vein thrombosis having hypercoagulable VHA values compared with healthy controls.9

Elevated clot strength, defined with maximum amplitude (MA; thrombelastography [TEG]) or maximum clot firmness (rotational thrombelastography), is a particularly important variable, as it has been repeatedly identified as a risk factor for thrombotic complications.4–6,8 Clot strength is a function of both fibrinogen and platelets.10 However, the majority of clot strength is attributable to platelets,11 which continue to evolve as an important process driving thrombotic complications in patients in the intensive care unit.12 A key limitation to using VHA to determine thrombotic complications is that measuring a stagnant pool of blood does not represent flow conditions as coagulation occurs in vivo. Understanding coagulation under flow conditions is becoming increasingly important for the assessment of bleeding and thrombotic complications in patients.13 Flow information also provides information on occlusion time (OT), which has direct clinical translation and cannot be determined by measurements of clot strength.

Total thrombus-formation analysis system (T-TAS) is a novel technique that uses a microchip flow chamber system to analyze the thrombus formation process under flow conditions. In addition to measuring the clotting parameters of whole blood, T-TAS can measure platelet specific coagulation properties. Our primary aim was to correlate T-TAS measurements of microvascular occlusion properties–in both whole blood and platelet function–to TEG measurements, within a heterogeneous population of healthy controls and patients presumed to be at risk of thrombotic complications. Our secondary aim was to assess the impact of tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) under flow versus nonflow conditions as recent evidence supports impaired fibrinolysis is also associated with thrombotic complications.14 We hypothesize that increased clot strength (MA) measured by TEG correlates to flow-dependent measurements of platelet-mediated microvascular occlusion by T-TAS and impaired clot degradation in the presence of t-PA.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Surgical patients at risk of thrombotic complications were enrolled in a Colorado Multi-Institutional Review Board study to prospectively collect blood samples preoperatively before their surgery. All patients were treated at the University of Colorado Hospital. Enrollment criteria were adult (>18 y) and patients undergoing elective surgery or endoscopy for inflammatory bowel disease or pancreatic cancer; in addition to five adult healthy volunteers. These patients represented a convenient sample as they required consent and the availability of a member of the research team capable of running both TEG and T-TAS assays. The specific number of patients per cohort was based on ongoing studies of coagulation in inflammatory bowel disease and pancreatic cancer–both having a consistent and predictable enrollment potential of patients during the 30 d period, in which the microfluidic device was available to the research team (i.e., in the given 30 d, we anticipated we could enroll 15 patients with pancreatic cancer and 10 patients with inflammatory bowel disease). Inflammatory bowel disease and pancreatic cancer patients were analyzed together as a single hypercoagulable group so that direct comparisons could be made to controls, and not between the two groups themselves–which explanations for any shared or differing properties related to their coagulopathies are unknown.

Thrombelastography

TEG assays were not performed on these patients as part of their routine preoperative coagulation assessment. Both TEG and T-TAS assays were performed in separate lab environments. Preoperative blood samples were drawn in the operating room after intubation and before incision. Blood was collected in citrated tubes and assayed at room temperature between 20 min and 2 h after blood draw, as per manufacturer’s guidelines. The citrated samples were recalcified and assayed using the TEG 5000 Thrombelastograph Hemostasis Analyzer (Haemonetics, Braintree MA) per manufacturer instructions. Clot formation, strength, and fibrinolysis were measured using standard TEG measurements including reaction time (R time), angle, MA, and clot lysis 30 min after MA (LY30). An additional t-PA TEG was also run in parallel with these assays to determine the clots susceptibility to fibrinolysis. The methods for running the high dose (150 ng/mL) t-PA TEG challenge have previously been reported.15 All TEG tracings were used for research purposes and not available to the surgeons or anesthesiologists.

Total thrombin-formation analysis system

The collected blood samples were run in tandem with the TEG samples. Citrated samples were assayed according to the manufacturer’s guidelines, equipment, and training (DiaPharma Group Inc, West Chester OH). T-TAS uses both an AR chip and a PL chip to analyze samples for separate characteristics. The AR chip is used to analyze thrombus formation mediated by fibrin and platelet activation and is characterized by a collagen- and thromboplastin-coated microchip. The PL chip is used to quantify platelet adhesion and aggregation, granule secretion, and thrombus growth.16 Clot formation, rate, and strength were measured using standard T-TAS measurements including occlusion start time (min:s), OT (min:s), occlusion speed (OSp, kPa/min), and total clot generation (area under the curve, kPa*time). These T-TAS measurements were correlated to significant TEG indices that were characteristic of hypercoagulability.

A modified t-PA challenge was developed with the T-TAS AR chip. t-PA was added to the citrated whole blood chamber 30 s before adding the specimen blood to the reservoir container. Serial concentrations of t-PA (75 ng-1000 ng) were added to healthy volunteers to identify a threshold to cause clot lysis before the machine could reach complete occlusion. This was found to be a concentration of 600 ng/mL of t-PA. All of the t-PA concentrations below this threshold were unable to cause clot lysis before the machine would terminate the assay due to a complete channel occlusion and backup pressure turning the test off. To preserve the machine mechanics, the T-TAS assays are programmed to shut off when the measured pressure exceeds 80 or 60 kPa above baseline pressure, for the AR chip and PL chip, respectively.

Hypercoagulability

Hypercoagulability was defined by previous healthy control data with a citrated native TEG (n = 141) using the extreme (5th or 95th percentile) of each variable associated with increased clotting capacity or impaired fibrinolysis. These patient’s data have been used in previous studies to define hypercoagulability in trauma patients using a rapid TEG.17 However, because native TEG has been reported to be more sensitive for detecting hypercoagulability, we selected to use only a citrated native assay for this study.18 The cut points for hypercoagulability based on citrated native TEG were as follows: R <10.2 min, angle >59 deg, MA >66 mm, LY30 <0.2%. These criteria were used to classify T-TAS data that was characteristic of a hypercoagulable state, which was then correlated to TEG indices.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 22 software (IBM, Armonk, NY). Data was described as the median value with the 25th to 75th percentile values. Correlation of TEG versus T-TAS values were conducted with a Spearman’s rho test. Paired tests with t-PA versus non–t-PA assays were contrasted with a Wilcoxon test for both TEG and T-TAS as-says. Hypercoagulable versus nonhypercoagulable TEG indices were then tested between controls with a chi squire test. Patients were stratified by each TEG variable defined by hypercoagulable versus nonhypercoagulable and T-TAS values were contrasted between groups with a Mann–Whitney U test. Significance was set to alpha of 0.05.

Results

Patient population

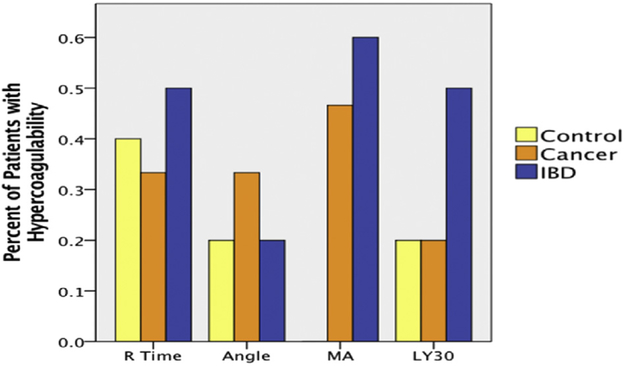

There were 30 patients included in the analysis, 15 with pancreatic cancer, 10 with inflammatory bowel disease, and five healthy volunteers. The overall percent of patients with hypercoagulable TEG measurements are displayed in Figure 1. In general, patients with inflammatory bowel disease tended to have more hypercoagulable TEG indices. Although the study was not designed to show a significant difference between controls and patient populations there was an increase in number of patients with hypercoagulable MA measurements between groups (52% [inflammatory bowel disease {IBD}/cancer] versus 0% [controls] P = 0.052).

Fig. 1 -.

Comparison of patient populations for hypercoagulable conditions. The figure shows a generally higher tendency of hypercoagulable qualifying conditions–as measured by TEG–for patients with IBD compared with pancreatic cancer and control patients. Specific to MA, together both IBD and cancer patients were qualified as hypercoagulable in comparison with the controls. (Color version of figure is available online.)

T-TAS AR chip and TEG measurements with and without t-PA

The addition of t-PA to the T-TAS device changed all clotting parameters in the 30 subjects. t-PA significantly prolonged occlusion start time (8:14 versus 6:30 min, P <0.001), prolonged OT (11:25 versus 9:30, P <0.001), reduced OSp (26 versus 30 kPa/min, P <0.001), and reduced total clot generation represented by area under the curve (1596 versus 1776 kPa*min, P <0.001). The addition of t-PA changed three of the four TEG variables measured in these patients. R time was shortened (7.9 versus10.9 min, P <0.001), MA was reduced (50 versus 65 mm, P <0.001), and LY30 was increased (0.5% versus 43.2%, P <0.001), but there was no difference in angle (54 versus 53°, P = 0.967).

TEG correlation to T-TAS

TEG parameters did not correlate with T-TAS AR chip measurements (Table 1). This was also true with the PL chip, although there were two comparisons that were weak correlations by rho and nonsignificant by t-test–an inverse relationship between TEG MA and a reduction in OT (−0.305 P = 0.108) and a direct relationship between TEG MA and an increase in OSp (0.334 P = 0.077 [Table 2]). When evaluating the t-PA challenge in TEG and the T-TAS AR chip, several correlations were appreciated (Table 3). This included T-TAS AR chip OSp showing an inverse relationship with TEG angle (−0.477 P = 0.012) and LY30 (−0.449 P = 0.019), and a positive correlation with R time (0.441 P = 0.021). A t-PA challenge was not tested on the PL chip.

Table 1 -.

Correlation of T-TAS AR chip to TEG indices.

| AR chip | OST (time) | OT (time) | OSp (kPa/min) | AUC (kPa*time) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| R | ||||

| Rho | −0.078 | −0.202 | 0.021 | 0.163 |

| P value | 0.686 | 0.294 | 0.915 | 0.399 |

| Angle | ||||

| Rho | 0.003 | 0.100 | 0.009 | −0.072 |

| P value | 0.986 | 0.606 | 0.965 | 0.711 |

| MA | ||||

| Rho | −0.176 | −0.095 | 0.128 | 0.108 |

| P value | 0.361 | 0.623 | 0.516 | 0.577 |

| LY30 | ||||

| Rho | 0.103 | −0.056 | 0.397 | −0.034 |

| P value | 0.594 | 0.774 | 0.036 | 0.859 |

T-TAS indices: OST = occlusion start time; AUC = total clot generation. TEG indices: R time = reaction time; angle = rate of clot formation.

Table 2 -.

Correlation of T-TAS PL chip to TEG indices.

| PL chip | OST (time) | OT (time) | OSp (kPa/min) | AUC (kPa*time) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| R | ||||

| Rho | −0.034 | −0.072 | 0.098 | 0.037 |

| P value | 0.860 | 0.710 | 0.614 | 0.849 |

| Angle | ||||

| Rho | 0.168 | −0.019 | 0.012 | 0.013 |

| P value | 0.384 | 0.923 | 0.950 | 0.947 |

| MA | ||||

| Rho | 0.081 | −0.305 | 0.334 | 0.299 |

| P value | 0.676 | 0.108 | 0.077 | 0.115 |

| LY30 | ||||

| Rho | −0.029 | −0.148 | 0.129 | 0.087 |

| P value | 0.881 | 0.444 | 0.504 | 0.654 |

T-TAS indices: OST = occlusion start time; AUC = total clot generation. TEG indices: R time = reaction time; angle = rate of clot formation.

Table 3 -.

Correlation of T-TAS AR chip to TEG indices, both with t-PA challenges.

| AR chip (t-PA) | OST (time) | OT (time) | OSp (kPa/min) | AUC (kPa*time) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| R | ||||

| Rho | 0.068 | −0.221 | 0.441 | 0.122 |

| P value | 0.730 | 0.259 | 0.021 | 0.536 |

| Angle | ||||

| Rho | 0.100 | 0.337 | −0.477 | −0.273 |

| P value | 0.612 | 0.079 | 0.012 | 0.160 |

| MA | ||||

| Rho | 0.136 | 0.174 | −0.081 | −0.140 |

| P value | 0.491 | 0.375 | 0.686 | 0.478 |

| LY30 | ||||

| Rho | 0.109 | 0.190 | −0.449 | −0.235 |

| P value | 0.580 | 0.332 | 0.019 | 0.229 |

T-TAS indices: OST = occlusion start time; AUC = total clot generation. TEG indices: R time = reaction time; angle = rate of clot formation.

T-TAS measurements in patients with TEG-detected hypercoagulability

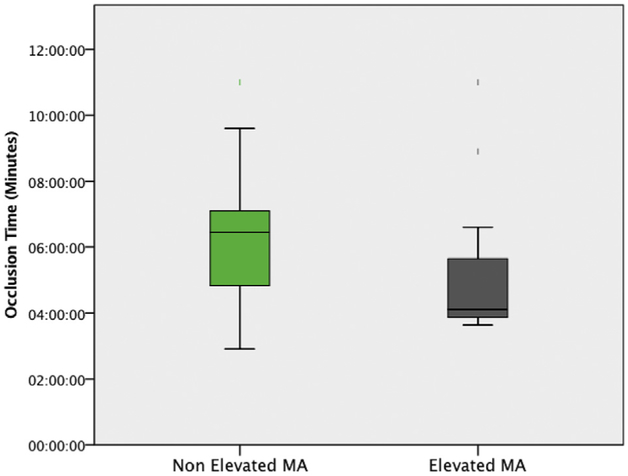

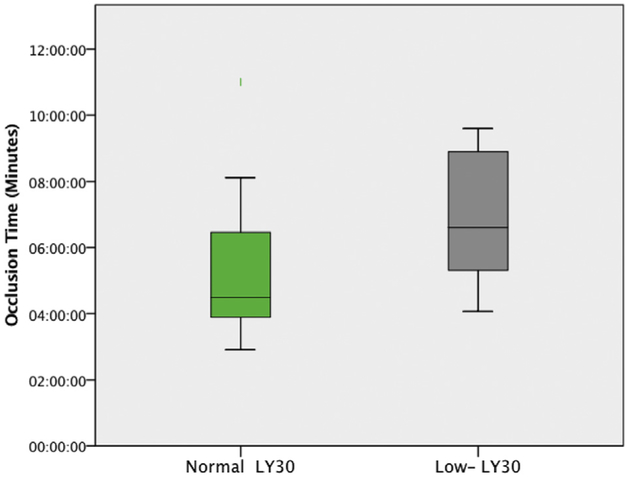

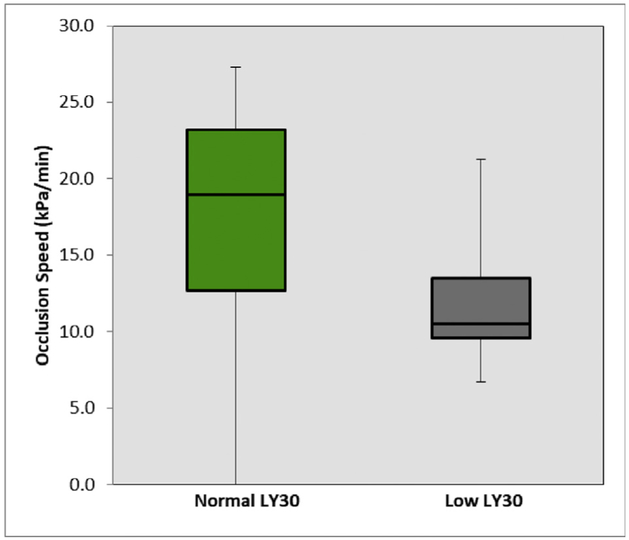

When distinguishing T-TAS indices for predictability of hypercoagulability, there were no T-TAS AR chip measurements that were statistically significant for any patient with hypercoagulability determined by different TEG indices (Tables 1 and 3). However, T-TAS PL chip measurements were significant between patients with TEG-detected hypercoagulability by elevated MA and low LY30. Patients with an elevated MA had a significantly reduced PL OT (4:07 [3:52–5:39] versus 6:27 [4:50–7:06] min, P = 0.043 Fig. 2). Patients with a low LY30 had a significantly prolonged PL OT (6:36 [5:19–8:54] versus 4:30 [3:54–6:28] min, P = 0.044 Fig. 3) and a slower OSp (10.5 [9.6–13.5] versus 19.0 [12.7–23.2] kPa/min, P = 0.030 Fig. 4). Patients with low LY30 had expectedly lower t-PA TEG LY30 (32% versus 47%), but did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.700) due to high variability as patients with a low LY30 for a t-PA TEG ranged from 7% to 57%, whereas LY30 for non–t-PA TEG ranged from 1% to 74%.

Fig. 2 -.

The reduced PL occlusion time for hypercoagulable patients as defined by an elevated TEG MA. Nonhypercoagulable patients had a median occlusion time of 6:27 min (4:50–7:06), and hypercoagulable patients had a median occlusion time of 4:07 min (3:52–5:39) (P = 0.043). (Color version of figure is available online.)

Fig. 3 -.

The prolonged PL occlusion time for hypercoagulable patients as defined by a low TEG LY30. Nonhypercoagulable patients had a median occlusion time of 4:30 min (3:54–6:28), and hypercoagulable patients had a median occlusion time of 6:36 min (5:19–8:54) (P = 0.044). (Color version of figure is available online.)

Fig. 4 -.

The slower PL occlusion speed for hypercoagulable patients as defined by a low TEG LY30. Nonhypercoagulable patients had a median occlusion speed of 19.0 kPa/min (12.7–23.2), and hypercoagulable patients had a median occlusion speed of 10.5 kPa/min(9.6–13.5) (P = 0.030). (Color version of figure is available online.)

Discussion

In a heterogeneous patient population, TEG variables consistent with hypercoagulability defined by MA were more common in patients with pancreatic cancer and inflammatory bowel disease compared with healthy controls. The addition of t-PA to whole blood in this patient population caused significant changes in all T-TAS measurements, and three of four measurements with TEG. Angle was spared from the effects of t-PA, which is expected as fibrinogenolysis requires doses of t-PA 20-fold higher than levels used in our study.19 However, there were no TEG variables that correlated with the whole blood AR chip read out, and the same was true with the PL chip. The t-PA TEG correlated to t-PA T-TAS AR chip assay with several correlations to OT and OSp. It was anticipated that LY30 would inversely correlate with OSp, and R time would have a direct correlation with OSp. However, it was unexpected that angle had an inverse correlation with OSp. When evaluating patients defined as hypercoagulable with TEG there were again no T-TAS AR chip measurements that differed by group, but several differences were appreciated with the PL chip, including a shorter OT in patients with elevated MA. Unexpectedly, patients with a low LY30 had longer PL OTs and slower OSps.

T-TAS has shown recent utility in identifying hemostasis-related diseases such as Von Willebrand disease.20 Other work has evaluated the ability of T-TAS to be used with rotational thrombelastography to understand the utility of T-TAS when treating patients with dabigatran.21 T-TAS has also been shown to have utility in periprocedural analysis of bleeding events for patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.22 However, no prior assessments of T-TAS have been made in predicting thrombotic complications. One limitation with T-TAS and the AR chip is utilization of tissue factor (tF) and collagen as an activator of clotting. This is representative of clotting at the level of vascular injury with maximal stimulation of platelets via rapid thrombin generation with tF and collagen.23 Previous work has demonstrated that native and kaolin TEGs detect higher rates of hypercoagulability in trauma patients.18,24 Our data supports that the PL chip appears to have higher utility in defining hypercoagulability as it has eliminated fibrin and thrombin generation to when the clot is being formed and has data consistent with TEG measurements in which an elevated MA is associated with a shorter platelet OT. The role of platelets in increasing clot strength, and an associated increased risk of thrombotic complications has been previously described.25,26 To our surprise 40% of our controls had short R time, which one would expect to also be a function of platelet activity. However, R time has not been proven to be associated with thrombotic complications in previous studies8,9,12 and may not be a clinically useful parameter.

Fibrinolysis measurements with TEG contrasted to T-TAS measurements resulted in several unanticipated results. A low LY30 was associated with a longer platelet OT and slower clotting speed. Prior evidence supports that fibrinolysis is inversely correlated to platelet function18 and we would have anticipated increased platelet OSp and decreased OT in patients with a low LY30. The slower rate of platelet occlusion with deceased fibrinolysis is perplexing, particularly when an elevated MA is associated with a faster OSp. However, several studies identifying different phenotypes of post injury coagulation abnormalities have demonstrated that these processes of fibrinolytic activity and clot formation are not linked.11,27,28 A potential explanation for slower OSp and decreased fibrinolysis may be related to the structural integrity of the clot. Prior studies on fibrin formation and clot resistance have demonstrated that slow growing clots with multiple side branches are fibrinolytic resistant.29,30 This was supported by our data in which TEG angle (a measurement of fibrinogen function) was inversely related to OSp in the AR chip in the presence of t-PA, whereas LY30 unexpectedly inversely correlated with OT. As the PL chip neglects any contribution of fibrinogen to clot, these patients potentially could have had an adaptive response to downregulate their platelets from increased fibrinogen function. This unexpected finding of a low LY30 linked to a low platelet OT and speed warrants ongoing investigation for validation and identification of a mechanism.

There are several limitations to be taken into consideration in this exploratory study. The T-TAS machine is a novel device that was not designed to detect hypercoagulability. Although few correlations to TEG were found, T-TAS has been proven to predict nonoperative procedural bleeding events.22,31 However, the utility of microfluidics to risk stratify patients for postoperative thrombotic complications remain largely unexplored. Other pathologic occlusion events in disease states such as sickle cell disease,32 tumors,33 and cardiovascular disease34 have been tested in in vitro models, but have not been used clinically to risk stratify patients. Recent work with computational modeling paired with microfluidic devices suggest that flow is critical for determining the risk of vascular occlusion, particularly in arterial shear rates.35 However, analysis under flow conditions presents multiple new variables such as open versus closed systems, shear rates, differences in polymer surfaces, and different clot activators.36 What flow conditions are optimal for predicting hypercoagulability remain unknown. As previously mentioned, a potential flaw of the T-TAS for measuring hypercoagulability could be a collagen and tF surface producing maximal clot generation. A more inert activating surface may better stratify patients with pathologic versus physiologic clotting when screening for thrombotic complications. On the near horizon new devices such as the TEG-6S, combine viscoelastic, and microfluidic measurements for assessing hemostasis and predicting thrombosis,37 which may or may not have a benefit in the prediction of hypercoagulability over conventional viscoelastic assays. We are unaware of any thrombotic complications in the patients analyzed. Even if a venous thromboembolism (VTE) occurred, we would be under powered to make any definitive conclusions as VTE occurrence is thought to be 23% in pancreatic cancer, and only 1%−8% in IBD patients38,39–which would have equated to potentially three VTEs in our study cohort. The t-PA–challenged T-TAS assays required a concentration of 600 ng/mL to induce clot degradation, four times greater than 150 ng/mL used to cause lysis in TEG.15 This raises concerns for the comparability of TEG to T-TAS, as dilution and variance in viscosity complicate differences between the stagnant and flow conditions.40,41 Another limitation of our study is the inherent qualitative difference of the LY30 metric in relation to T-TAS’s settings for both PL and AR chips. In TEG, LY30 is a measurement obtained after MA is reached, but T-TAS stops running its assay before an MA or LY30 equivalent is measured as T-TAS’s design includes a preset pressure ceiling to stop running the assay at ~80 kPa for the AR chip and ~60 kPa for the PL chip. Thus, despite LY30 having been shown to be a valid predictor of hypercoagulability, it is difficult to distinguish correlations to T-TAS measurements that are limited to the phases when the hemostatic balance favors the clot formation process over the fibrinolysis process.26,42,43 Finally, it is important to recognize the differences in flow speeds between our tested arterial flow and known differing venous flow speeds, which limit the degree to which this data can be used to explain venous-specific complications such as venous thromboembolic events.44,45 As TEG determines thrombotic capacity in a low shear system, it may be more reflective of venous thromboembolism risk. Whereas T-TAS is a high shear system, which may be more reflective of arterial thrombosis risk. Partitioning these systems may prove useful in elucidating the seemingly paradoxical phenomena in which both acute liver failure patients46 and end-stage renal disease patients47 have known bleeding risks but are also hypercoagulable and at high risk for VTE.

In conclusion, TEG and T-TAS have poor correlation when comparing whole bloods ability to from a clot. From our study, the only result that aligned with our hypothesis was that an elevated MA was associated with decreased OT with platelets–which is supplemental to the clinical data supporting the use of antiplatelet medication to reduce thrombotic complications in high-risk patients. At this time, it remains uncertain if T-TAS is an appropriate clinical or research tool for assessing hypercoagulation as T-TAS has not shown utility in correlations to known TEG associations with thrombotic complications. This may not be generalizable to different microfluidic devices, which remain an unexplored arena in thrombosis research in surgery and warrants ongoing investigation.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported in part by National Institute of General Medical Sciences grants: T32-GM008315, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute UM1-HL120877, and department of surgery academic enrichment fund. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Additional research support was provided by Haemonetics and DiaPharma with shared intellectual property.

Footnotes

Presented at the Academic Surgical Congress Jacksonville FL, February 2018.

Disclosure

The authors reported no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

R E F E R E N C E S

- 1.Geerts WH, Code KI, Jay RM, Chen E, Szalai JP. A prospective study of venous thromboembolism after major trauma. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1601–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, et al. American College of chest P. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e278S–e325S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kashuk JL, Moore EE, Sabel A, et al. Rapid thrombelastography (r-TEG) identifies hypercoagulability and predicts thromboembolic events in surgical patients. Surgery. 2009;146:764–772. discussion 72–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brill JB, Badiee J, Zander AL, et al. The rate of deep vein thrombosis doubles in trauma patients with hypercoagulable thromboelastography. J Trauma acute Care Surg. 2017;83:413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zanetto A, Senzolo M, Vitale A, et al. Thromboelastometry hypercoagulable profiles and portal vein thrombosis in cirrhotic patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49:440–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hincker A, Feit J, Sladen RN, Wagener G. Rotational thromboelastometry predicts thromboembolic complications after major non-cardiac surgery. Crit Care. 2014;18:549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Senchenkova E, Seifert H, Granger DN. Hypercoagulability and platelet abnormalities in inflammatory bowel disease. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2015;41:582–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toukh M, Siemens DR, Black A, et al. Thromboelastography identifies hypercoagulablilty and predicts thromboembolic complications in patients with prostate cancer. Thromb Res. 2014;133:88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spiezia L, Marchioro P, Radu C, et al. Whole blood coagulation assessment using rotation thrombelastogram thromboelastometry in patients with acute deep vein thrombosis. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2008;19:355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whiting D, DiNardo JA. TEG and ROTEM: technology and clinical applications. Am J Hematol. 2014;89:228–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kornblith LZ, Kutcher ME, Redick BJ, Calfee CS, Vilardi RF, Cohen MJ. Fibrinogen and platelet contributions to clot formation: implications for trauma resuscitation and thromboprophylaxis. J Trauma acute Care Surg. 2014;76:255–256. discussion 62–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harr JN, Moore EE, Chin TL, et al. Platelets are dominant contributors to hypercoagulability after injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74:756–762. discussion 62–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casa LDC, Ku DN. thrombus formation at high shear rates. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2017;19:415–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leeper CM, Neal MD, McKenna C, Sperry JL, Gaines BA. Abnormalities in fibrinolysis at the time of admission are associated with deep vein thrombosis, mortality, and disability in a pediatric trauma population. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82:27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore HB, Moore EE, Chapman MP, et al. Viscoelastic tissue plasminogen activator challenge predicts massive transfusion in 15 minutes. J Am Coll Surgeons. 2017;225:138–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamaguchi Y, Moriki T, Igari A, et al. Studies of a microchip flow-chamber system to characterize whole blood thrombogenicity in healthy individuals. Thromb Res. 2013;132:263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore HB, Moore EE, Liras IN, et al. Targeting resuscitation to normalization of coagulating status: hyper and hypocoagulability after severe injury are both associated with increased mortality. Am J Surg. 2017;214:1041–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore HB, Moore EE, Chapman MP, et al. Viscoelastic measurements of platelet function, not fibrinogen function, predicts sensitivity to tissue-type plasminogen activator in trauma patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13:1878–1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Godier A, Parmar K, Manandhar K, Hunt BJ. An in vitro study of the effects of t-PA and tranexamic acid on whole blood coagulation and fibrinolysis. J Clin Pathol. 2017;70:154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daidone V, Barbon G, Cattini MG, et al. Usefulness of the Total Thrombus-Formation Analysis System (T-TAS) in the diagnosis and characterization of von Willebrand disease. Haemophilia. 2016;22:949–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taune V, Wallen H, Agren A, et al. Whole blood coagulation assays ROTEM and T-TAS to monitor dabigatran treatment. Thromb Res. 2017;153:76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oimatsu Y, Kaikita K, Ishii M, et al. Total thrombus-formation analysis system predicts periprocedural bleeding events in patients with coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu Y, Lee MY, Zhu S, Sinno T, Diamond SL. Multiscale simulation of thrombus growth and vessel occlusion triggered by collagen/tissue factor using a data-driven model of combinatorial platelet signalling. Math Med Biol. 2017;34:523–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Connelly CR, Van PY, Hart KD, et al. Thrombelastography-based dosing of enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis in trauma and surgical patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:e162069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meier K, Saenz DM, Torres GL, et al. Thrombelastography suggests hypercoagulability in patients with renal dysfunction and intracerebral hemorrhage. J stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;27:1350–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chapman MP, Moore EE, Burneikis D, et al. Thrombelastographic pattern recognition in renal disease and trauma. J Surg Res. 2015;194:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chapman MP, Moore EE, Ramos CR, et al. Fibrinolysis greater than 3% is the critical value for initiation of antifibrinolytic therapy. J Trauma acute Care Surg. 2013;75:961–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White NJ, Contaifer D Jr, Martin EJ, et al. Early hemostatic responses to trauma identified with hierarchical clustering analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13:978–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sambola A, Garcia Del Blanco B, Ruiz-Meana M, et al. Increased von Willebrand factor, P-selectin and fibrin content in occlusive thrombus resistant to lytic therapy. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115:1129–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ammollo CT, Semeraro F, Incampo F, Semeraro N, Colucci M. Dabigatran enhances clot susceptibility to fibrinolysis by mechanisms dependent on and independent of thrombinactivatable fibrinolysis inhibitor. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:790–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ito M, Kaikita K, Sueta D, et al. DTotal Thrombus-formation analysis system (T-TAS) can predict periprocedural bleeding events in patients undergoing catheter ablation for Atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horton RE. Microfluidics for investigating vaso-occlusions in sickle cell disease. Microcirculation. 2017;24:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goerge T, Kleineruschkamp F, Barg A, et al. Microfluidic reveals generation of platelet-strings on tumor-activated endothelium. Thromb Haemost. 2007;98:283–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Westein E, van der Meer AD, Kuijpers MJ, Frimat JP, van den Berg A, Heemskerk JW. Atherosclerotic geometries exacerbate pathological thrombus formation poststenosis in a von Willebrand factor-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1357–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ku DN, Casa LDC, Hastings SM. Choice of a hemodynamic model for occlusive thrombosis in arteries. J Biomech. 2017;50:110–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colace TV, Tormoen GW, McCarty OJ, Diamond SL. Microfluidics and coagulation biology. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2013;15:283–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, Tantry US, et al. First report of the point-of-care TEG: a technical validation study of the TEG-6S system. Platelets. 2016;27:642–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Magro F, Soares JB, Fernandes D. Venous thrombosis and prothrombotic factors in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:4857–4872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khorana AA, Rubens D, Francis CW. Screening high-risk cancer patients for VTE: a prospective observational study. Thromb Res. 2014;134:1205–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agirbasli MA, Song J, Lei F, et al. Comparative effects of pulsatile and nonpulsatile flow on plasma fibrinolytic balance in pediatric patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. Artif organs. 2014;38:28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Helenius G, Hagvall SH, Esguerra M, Fink H, Soderberg R, Risberg B. Effect of shear stress on the expression of coagulation and fibrinolytic factors in both smooth muscle and endothelial cells in a co-culture model. Eur Surg Res. 2008;40:325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hosokawa K, Ohnishi T, Fukasawa M, et al. A microchip flow-chamber system for quantitative assessment of the platelet thrombus formation process. Microvasc Res. 2012;83:154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hosokawa K, Ohnishi T, Kondo T, et al. A novel automated microchip flow-chamber system to quantitatively evaluate thrombus formation and antithrombotic agents under blood flow conditions. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:2029–2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gorog DA, Fayad ZA, Fuster V. Arterial Thrombus Stability: Does It Matter and Can We Detect it? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2036–2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chandrashekar A, Singh G, Jonah G, Sikalas N, Labropoulos N. Mechanical and Biochemical Role Of fibrin within a venous thrombus. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018;55:417–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Agarwal B, Wright G, Gatt A, et al. Evaluation of coagulation abnormalities in acute liver failure. J Hepatol. 2012;57:780–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Darlington A, Ferreiro JL, Ueno M, et al. Haemostatic profiles assessed by thromboelastography in patients with end-stage renal disease. Thromb Haemost. 2011;106:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]