Abstract

Introduction

Uveal melanoma is a rare tumour caused by genetic factors and alterations in the immune response. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a multifactorial chronic inflammatory disorder characterized by an inappropriate or excessive immune response. The two main types of IBD are Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). A diagnosis of IBD and the use of immunosuppressive drugs are both independently associated with an increased risk of developing skin melanoma. The association between IBD and uveal melanoma (UM) has not been previously described.

Cases description

Two young Caucasian men, aged 24 and 28, developed UM 3 and 15 years, respectively, after being diagnosed with IBD. Both received long-term treatment with immunomodulatory drugs, with periodic switching among the drugs due to the refractory nature of IBD. In both cases, melanoma was treated by brachytherapy with iodine-125 COMS plaque implant at a dose of 75 Gy.

Discussion

Chronic inflammation can promote cell proliferation and growth. The use of immunomodulatory drugs is associated with an increased risk of developing melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer. The two patients described in this report both had long-standing IBD treated with immunomodulatory drugs. It seems reasonable to suggest that these two factors may have promoted the development of uveal melanoma. More studies are warranted to investigate and confirm this possible association.

Keywords: Brachytherapy, Crohn's disease, IBD, Immunomodulatory drugs, Uveal melanoma, Ulcerative colitis

1. Introduction

Although uveal melanoma is rare, it is the most common primary intraocular malignancy in adults, with an average incidence of 5.1 cases per million population. The median age at diagnosis is 62 years, although the age at diagnosis can range from 6 to 100 years.1 Skin melanoma is an immunogenetic tumour frequently observed in patients whose normal immune response is suppressed, thus allowing cancer cells to grow.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is chronic multifactorial disorder involving a complex interaction between genetic, environmental, microbial, and innate and adaptive immune factors. An inappropriate or excessive immune response causes cytokine dysregulation and chronic inflammation. The two main types of IBD are Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), which together have an overall prevalence of approximately 0.4% in both Europe and the United States.2 Numerous studies have shown that IBD is associated with an increased risk of developing non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC).3, 4, 5, 6, 7

A comprehensive meta-analysis was performed of more than 170,000 patients diagnosed with IBD to determine the risk of melanoma in patients with IBD. They found 179 cases of melanoma and calculated that patients with IBD had a 37% higher risk of developing melanoma than expected in a general population.8 Importantly, the patients in that sample who took immunomodulators had an even greater risk of developing skin melanoma.

To our knowledge, no previous reports have described the correlation between IBD and uveal melanoma, although Damento et al. suggested a possible relationship between progression—but not onset—of uveal melanoma after tumour necrosis factor (TNF)—a inhibitor intake in a small case series.9 In the present case report, we describe two young adult males diagnosed with IBD who subsequently developed uveal melanoma. We performed a literature review to examine a possible relationship between uveal melanoma and IBD.

2. Cases description

2.1. Patient 1

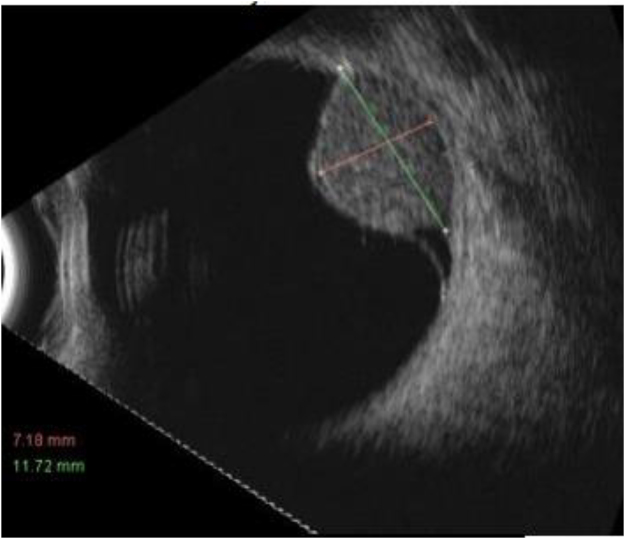

D.T.C. is a 28-year-old male diagnosed with rapidly-progressing UC at age 15. The disease was resistant to both corticosteroid and immunosuppressant treatment. After two years of treatment with monoclonal anti-TNF antibodies (Infliximab, Adalimumab), the patient underwent an ileostomy due to poor disease control. Since age 16, the patient has been receiving treatment with Azathioprine 50 mg twice daily. He has no family history of melanoma. Twelve years after the diagnosis of UC, the patient developed ciliary body melanoma in the right eye, measuring 15 mm × 11 mm, with a thickness of 8.8 mm (Fig. 1). Chest-ray and abdominal ultrasound were performed to rule out metastasis. Treatment consisted of insertion of an iodine-125 COMS plaque around the tumour to administer 75 Gy (0.84 Gy/h) to the tumour apex. Six months post-treatment, the patient is currently free of disease.

Fig. 1.

Ocular ultrasound that highlights the uveal melanoma in patient no. 1.

2.2. Patient 2

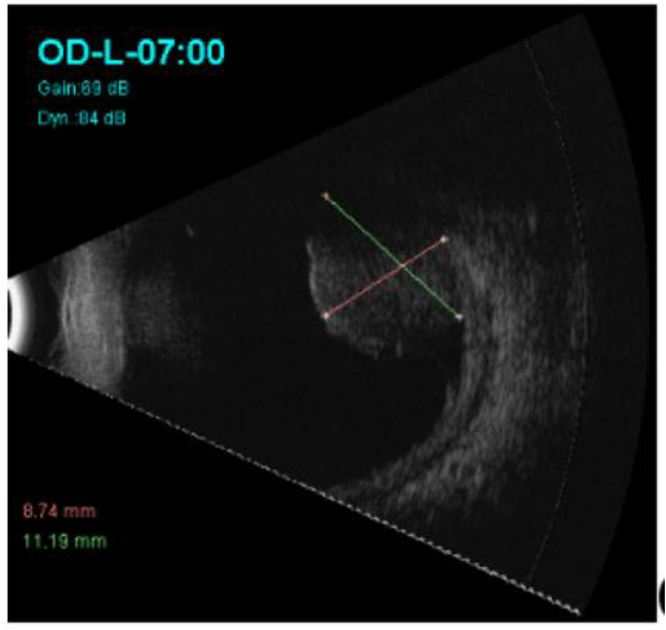

A.J.A. is a 24-year-old man diagnosed with UC at age 20. The patient received treatment with corticosteroids plus Mesalazine for one year. Due to intolerance to Mesalazine, treatment was switched to Azathioprine for the following 3 years. Three years after the initial diagnosis of UC, the patient developed a right choroidal melanoma measuring 16 mm × 15 mm with a thickness of 8 mm (Fig. 2). No metastatic lesions were detected. The patient's family history includes UC but no melanoma. After undergoing transscleral surgical resection to remove the lesion, the patient underwent adjuvant brachytherapy with iodine-125 COMS plaque implant, receiving 75 Gy to the tumour bed. The patient has recently (18 months after brachytherapy treatment) developed a single liver metastasis, which is currently being evaluated.

Fig. 2.

Ocular ultrasound that highlights the uveal melanoma in patient no. 2.

3. Discussion

Both of these cases share several characteristics: young men in their twenties with a long history of IBD, long-term use of immunomodulatory drugs, and a diagnosis of uveal melanoma in the third decade of life.

IBD is a well-known risk factor for skin melanoma. Indeed, patients with IBD had a 37% higher risk of developing melanoma than expected in the general population.8, 10, 11 However, the underlying mechanisms for developing skin melanoma and NMSC in patients with IBD are not entirely clear, although this increased risk in these patients could be due to immune dysfunction resulting in altered tumour surveillance and the use of immunomodulators.

Chronic inflammation can initiate tumours by directly inducing DNA damage or by making cells more susceptible to mutagens.12, 13, 14

In addition, inflammation can act as a tumour promoter. Inflammatory mediators—including cytokines such as TNF, interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6, growth factors, and chemokines, as well as proteases produced by tumour-associated lymphocytes and macrophages—can enhance tumour cell growth by promoting survival and proliferation of these cells. Tumour-associated macrophages release inflammatory mediators that stimulate tumour angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. The immunomodulators used to treat IBD also play an important role in tumour genesis.15, 16, 17, 18, 19

The association between TNF inhibitors and the risk of developing melanoma has been the subject of intense debate.20

A nested case-control study conducted by Long et al. showed that the risk of melanoma was higher in patients treated with biologics, but not with immunomodulators.21 An analysis of the Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System carried out by McKenna et al.22 demonstrated that TNF-α inhibitor monotherapy or its concomitant use with thiopurines in patients with IBD is associated with a higher risk of developing melanoma and NMSC.

In the present report, we describe two patients diagnosed with IBD, both of whom were treated with immunomodulatory drugs. Both patients developed uveal melanoma—a rare disease. Although previous publications have demonstrated a correlation between IBD, immunomodulators, and skin melanoma, this is the first report to describe a possible correlation between IBD and uveal melanoma. We hypothesize that the uveal melanoma in these two patients is related to the IBD and the immunomodulatory treatments administered. More studies are warranted to investigate and confirm this possible association.

4. Conflict of interest

None declared.

5. Financial disclosure

None declared.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Bradley Londres for editing this manuscript.

References

- 1.Sing A.D., Tuller M.E., Topham A. Uveal melanoma: trends in incidence, treatment, and survival. Ophthalmology. 2011 Sep;118(9):1881–1885. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Molodecky N.A., Soon I.S., Rabi D.M. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46–54. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sifuentes H., Kane S. Monitoring for extra-intestinal cancers in IBD. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2015;17:42. doi: 10.1007/s11894-015-0467-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UrpoNieminen, Marti, Färkkilä Malignancies in inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:81–89. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2014.992041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marzano A., Borghi A., Meroni P.L. Immune-mediated inflammatory reactions and tumours as skin side effects of inflammatory bowel disease therapy. Autoimmunity. 2014;47(3):146–153. doi: 10.3109/08916934.2013.873414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Long M., Martin C., Pipkin C. Risk of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:390–399. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beyaert R., Beaugerie L., Van Assche G. Cancer risk in immune-mediated inflammatorydiseases (IMID) Mol Cancer. 2013;12:98. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh S., Nagpal S., Murad M. Inflammatory bowel disease is associated with an increased risk of melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:210–218. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damento G., Kavoussi S., Materin M. Clinical and histologic findings in patients with uveal melanomas after taking tumour necrosis factor-a inhibitors. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(11):1481–1486. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garg S.K., Loftus E.V., Jr. Risk of cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: going up, going down, or still the same? Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2016;32(4):274–281. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nissen L.H.C., Pierik M., Deriks L.A.A.P. Risk factors and clinical outcomes in patients with IBD with melanoma. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23811:2018–2026. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohnishi S., Ma N., Thanan R. DNA damage in inflammation-related carcinogenesis and cancer stem cells. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:387014. doi: 10.1155/2013/387014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grivennikov S.I., Karin M. Inflammation and oncogenesis: a vicious connection. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2010;20:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zumsteg A., Christofori G. Corrupt policemen: inflammatory cells promote tumor angiogenesis. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2009;21:60–70. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32831bed7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mantovani A., Allavena P., Sica A., Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solinas G., Germano G., Mantovani A., Allavena P. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) as major players of the cancer-related inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:1065–1073. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0609385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zamarron B.F., Chen W. Dual roles of immune cells and their factors in cancer development and progression. Int J Biol Sci. 2011;7:651–658. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayden M.S., Ghosh S. NF-κB, the first quarter-century: remarkable progress and outstanding questions. Genes Dev. 2012;26:203–234. doi: 10.1101/gad.183434.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J., Wu P., Hu Y. Clinical and marketed proteasome inhibitors for cancer treatment. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20:2537–2551. doi: 10.2174/09298673113209990122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Y., Friedman M., Liu G. Do tumor necrosis factor inhibitors increase cancer risk in patients with chronic immune-mediated inflammatory disorders? Cytokine. 2018 Jan;101:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2016.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Long M.D., Martin C.F., Pipkin C.A. Risk of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:390–399. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKenna M., Stobaugh D., Deepak P. Melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer in inflammatory bowel disease patients following tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitor monotherapy and in combination with tiopurines: analysis of the food and drug administration adverse event reporting system. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2014;23(3):267–271. doi: 10.15403/jgld.2014.1121.233.mrmk. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]