Abstract

The monitoring of players’ work-rate profiles during competition is now feasible through computer-aided motion analysis. The aim of the present study was to examine how various playing positions and match outcomes (i.e. won, drawn, lost) affect the total distance, and the distances covered at different intensities, by soccer players in Germany’s Bundesliga. Match performance data were collected for 556 soccer players competing in the Bundesliga during the 2014/15, 2015/16 and 2016/17 domestic seasons. A total of 13 039 individual match observations were made of outfield players (goalkeepers excluded). The analysis was carried out using an IMPIRE AG motion analysis system, with records of all players’ movements in all the 918 matches. The recorded variables included total distance covered [km] and distance covered at intensities in the ranges below 11 km/h, 11-14 km/h, 14-17 km/h, 17-21 km/h, 21-24 km/h, and above 24 km/h. In won matches, as opposed to drawn and lost matches, the wide midfielders and forwards ran a significantly longer distance, primarily covered at intensities of 21-23.99 and above 24 km/h (p ≤ 0.05). The analysis of full-backs, central defenders and central midfielders in won matches – as opposed to drawn and lost matches – in turn reveals that players ran a significantly shorter distance, most likely to be covered at intensities of 17-20.99 and 21-23.99 km/h (p ≤ 0.05). The results of the present study emphasise the importance of match outcome and playing positions during the assessment of physical aspects of soccer performance.

Keywords: Match analysis, Soccer, Intensity ranges, Match outcome, Playing positions, Activity profile

INTRODUCTION

In football, the physical demands of elite match play have increased substantially over the last decade [1, 2], with the result that the need for a player’s physical capacity to be optimised has received increasing attention [3]. Relevantly, the monitoring of players’ work-rate profiles during competition is now feasible through computer-aided motion analysis. Indeed, the recent technological developments in this area have ensured the wide application at elite soccer clubs of sophisticated systems capable of recording and processing data on all players’ physical contributions throughout entire matches [4, 5]. In the majority of time–motion analysis studies, physical activity data are expressed in terms of absolute values for distances covered in relation to a range of speed thresholds [6, 7]. However, the definitions of intensity ranges in soccer-match analysis vary among authors, inter alia as a reflection of the use made of the different advanced kinematic systems available, including AMISCO [8], OPTA [9], PROZONE [10] and IMPIRE AG [11]. Irrespective of the methods of collection employed, data obtained from motion analyses are translated into distances covered, and/or the amount of time devoted to a variety of discrete locomotor activities, in order that physical performance can be quantified and evaluated.

The aforesaid activities are commonly defined as walking, movement at low, moderate or high intensity, and sprinting. A soccer match typically sees professional players perform 150-250 different actions, with nearly 1100 changes of direction accomplished [12, 13]. Obviously, significant differences in the physical capabilities of individual players can be observed in this way, in line with players’ physical skills and team roles [14, 15]. Depending on the player formation and position on the pitch, a player’s physical activity changes every 4-6 seconds [16]. During a match players make enormous physical effort while moving on the pitch. As the intensity of movement involved requires the highest expenditure of energy, from the standpoint of physiological and motor assessment, this is a highly significant aspect of modern soccer [4, 13].

Activities of lower intensity, such as jogging and walking, tend to dominate players’ work-rate profiles, emphasising the predominantly aerobic nature of the game. However, several authors have stressed the importance of sprints and very high-intensity running for the actual outcomes of games [15, 17]. High-intensity running is one of the most important indicators of physical activity in elite soccer because it corresponds with the decisive short and intense actions that characterise the effort made by players [18, 19]. In this regard, it has been reported that the distance covered at high intensity seems a superior, more sensitive indicator of performance than total distance covered, as it correlates strongly with physical capacity [20]. In recent studies, Andrzejewski et al. [5, 13] reported that central defenders and full-backs covered shorter distances at high intensity in won matches than in lost matches. Furthermore, forwards and wide midfielders covered significantly longer sprint distances in won matches than in lost matches. However, there remains no analysis of the distances covered at different positions and at different ranges of intensity, in relation to game outcome. This is despite the fact that information of this kind could help coaches to tailor workload to individual players. Indeed, great awareness of the necessity for physical strain on players to be individualised has still not typically been reflected in conscientious implementation at the team level.

Nevertheless, several attempts have been made to identify performance indicators in association football that may distinguish winning teams from losing ones [21, 22, 23], as aspects of performance capable of being considered technical [15, 24], tactical [25, 26] or physical [27, 28], and even the effects of situation variables on previous performance indicators [29, 30, 31]. Although studies of the above kind have provided a great deal of valuable information about the behaviour of players during games, only a few have addressed large samples, and/or extended their analyses beyond a single season, especially in circumstances where players’ positions on the pitch are further related to match outcome (i.e. won, lost, or drawn).

Clearly, a search for the parameters really affecting match outcome is among modern football’s key issues [21, 22, 23]. Soccer coaches and sport scientists thus attempt to quantify players’ performances, with the aim of determining how particular games were won or lost, who played well, and what players’ strengths and weaknesses were [32]. They also attempt to identify in what intensity ranges in different playing positions soccer players can reduce or increase the covered distance in order to increase the probability of winning the match. Current data from the top European leagues may help indicate future directions in professional football training [5]. In that light, the study described here concerned the manner in which various playing positions and match outcomes (i.e. won, drawn, lost) might relate to total distances covered, as well as distances covered within different intensity ranges, by soccer players in the Bundesliga.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental approach to the problem

The initial hypothesis was that players’ positions on the pitch during a game and match outcome determine the total distance covered by players, as well as the distances they cover at different intensities. It was assumed that significant relationships would be present between players’ positions and variables analysed.

Players and match data

Match performance data were collected from 556 soccer players competing in the German Bundesliga during the 2014/2015, 2015/2016 and 2016/2017 domestic seasons. A total of 13 039 individual match observations were made of outfield players (goalkeepers excluded). These players were classified into five positional roles, i.e. central defenders (CD, match observations = 3592), full-backs (FB, match observations = 2794), central midfielders (CM, match observations = 3170), wide midfielders (WM, match observations = 1928), and forwards (F, match observations = 1555). Only data for players completing entire matches (i.e. on the pitch for the whole 90 min) were considered. Data were obtained using the IMPIRE AG system. The system generates official DFB (Deutscher Fußball-Bund) reports, which were then analysed and interpreted.

The following numbers of observations were subjected to analysis with regard to match outcome: wins = 4885 (CD = 1377; FB = 1081; CM = 1206; WM = 703; F = 518); draws = 3278 (CD = 888; FB = 683; CM = 821; WM = 484; F = 402); and losses = 4876 (CD = 1327; FB = 1030; CM = 1143; WM = 741; F = 635). Player mean body height was 183.92 ± 7.12 cm, mean body mass 78.57 ± 7.34 kg, and mean age 26.642 ± 4.03 years. The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee (No. 20/2017). The study protocol was also approved by the Board of Ethics of the University School of Physical Education in Wrocław.

Data collection and analyses

The analysis was carried out using an IMPIRE AG motion analysis system [33], providing records of all players’ movements in all 918 matches, with a sampling frequency of 25 Hz. IMPIRE AG (Ismaning, Germany) and Cairos Technologies AG (Karlsbad, Germany) provide a ready-to-use vision-based tracking system for team sports called VIS.TRACK. The system consists of two cameras and offers software tracking of both players and the ball [34]. The major advantages of vision-based systems lies in their high update rate corresponding to the camera frame rate, and the fact that the players and the ball are tracked simultaneously, i.e., each position sample for a single player has a corresponding position sample for every other player including the ball, measured at an identical point in time [35]. The validity and reliability of this system for taking such measurements have been described in detail elsewhere [33, 34, 36, 37]. The recorded variables included total distance covered [km] and distance covered [km] at intensity ranges of below 11 km/h, 11-14 km/h, 14-17 km/h, 17-21 km/h, 21-24 km/h, and above 24 km/h [6, 38, 39, 40].

Statistical analysis

All the variables were checked to verify their conformity with a normal distribution. Arithmetic means and standard deviations were calculated. Two-way ANOVA was used to compare mean values of the examined variables. The independent variables were match outcome and players’ positions. Where a significant difference was found, a Fisher LSD post-hoc test was performed to assess differences between means. The level of statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistica ver. 13.1 software package.

RESULTS

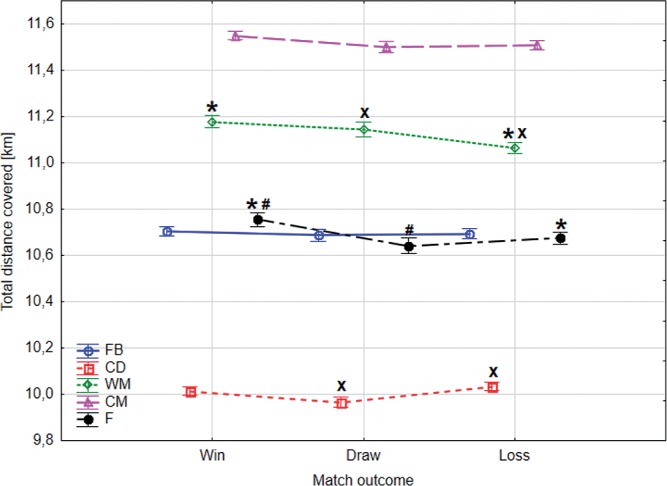

Data for total distance covered by players in the Bundesliga with regard to their positions on the pitch revealed that central defenders ran significantly shorter distances in drawn matches than in lost matches (p ≤ 0.05). Furthermore, the wide midfielders covered longer distances in won and drawn matches than in lost matches (p ≤ 0.05). Forwards likewise ran a significantly longer distance in won matches than in drawn matches and lost matches (p ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Total distance covered [km] in different playing positions and match outcome.

Statistically significant differences between won and lost matches: *(p ≤ 0.05); between wins and draws: #(p ≤ 0.05); between loses and draws: X(p ≤ 0.05). Playing positions: FB-full-back, CD-central defender, WM-wide midfielder, CM-central midfielder, F-forward.

Analysis of distance covered by players at intensities below 11 km/h showed that, regardless of position on the field, players ran significantly longer distances in won and drawn matches than in lost matches (p ≤ 0.05) (Table 1).

TAB. 1.

Differences in [km] distances covered at different intensities by soccer players in the Bundesliga, as set against match outcome (mean ± SD).

| Range of intensity | Positions | Match outcome |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Win | Draw | Loss | ||

| < 11 km/h | FB | 6.24 ± 0.32* | 6.23 ± 0.32X | 6.17 ± 0.32*X |

| CD | 6.36 ± 0.31* | 6.35 ± 0.32X | 6.30 ± 0.32*X | |

| WM | 6.26 ± 0.30* | 6.27 ± 0.31X | 6.22 ± 0.31*X | |

| CM | 6.19 ± 0.33* | 6.19 ± 0.35X | 6.10 ± 0.36*X | |

| F | 6.26 ± 0.30* | 6.27 ± 0.29X | 6.22 ± 0.32*X | |

| 11-13.99 km/h | FB | 1.79 ± 0.24 | 1.78 ± 0.24 | 1.77 ± 0.25 |

| CD | 1.66 ± 0.27 | 1.65 ± 0.28X | 1.68 ± 0.27X | |

| WM | 1.84 ± 0.30 | 1.84 ± 0.30 | 1.82 ± 0.28 | |

| CM | 2.22 ± 0.34 | 2.20 ± 0.33 | 2.22 ± 0.33 | |

| F | 1.70 ± 0.36 | 1.67 ± 0.36X | 1.72 ± 0.36X | |

| 14-16.99 km/h | FB | 1.15 ± 0.18 | 1.16 ± 0.20 | 1.17 ± 0.20 |

| CD | 0.97 ± 0.21 | 0.95 ± 0.20X | 0.98 ± 0.20X | |

| WM | 1.24 ± 0.23 | 1.25 ± 0.23 | 1.25 ± 0.24 | |

| CM | 1.54 ± 0.30 | 1.52 ± 0.31X | 1.55 ± 0.31X | |

| F | 1.11 ± 0.27 | 1.10 ± 0.26 | 1.13 ± 0.28 | |

Statistically significant difference between a win and a loss:

(p ≤ 0.05); between a win and a draw: #(p ≤ 0.05); between a loss and a draw:

(p ≤ 0.05). Playing positions: FB – full-back, CD – central defender, WM – wide midfielder, CM – central midfielder, F – forward.

Consideration of distances covered at intensities in the 11-13.99 km/h range in turn demonstrated that central defenders and forwards covered significantly shorter distances in drawn matches than in lost matches (p ≤ 0.05) (Table 1).

Where distances covered by players at an intensity range between 14 and 16.99 km/h were concerned, central defenders and central midfielders ran significantly less far in drawn than in lost matches (p ≤ 0.05) (Table 1).

Analysis of the distance covered by players at intensities of 17-20.99 km/h revealed that central defenders, full-backs and central midfielders covered significantly shorter distances in drawn and won matches than in lost ones (p ≤ 0.05) (Table 2).

TAB. 2.

Differences in [km] distances covered at different intensities by soccer players in the Bundesliga, as set against match outcome (mean ± SD).

| Range of intensity | Positions | Match outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Win | Draw | Loss | ||

| 17-20.99 km/h | FB | 0.87 ± 0.15* | 0.86 ± 0.17X | 0.90 ± 0.17*X |

| CD | 0.65 ± 0.15* | 0.64 ± 0.14X | 0.66 ± 0.14*X | |

| WM | 1.01 ± 0.19 | 1.00 ± 0.20 | 1.00 ± 0.20 | |

| CM | 1.05 ± 0.24* | 1.04 ± 0.25X | 1.07 ± 0.24*X | |

| F | 0.91 ± 0.20 | 0.89 ± 0.20 | 0.91 ± 0.20 | |

| 21-23.99 km/h | FB | 0.36 ± 0.08* | 0.36 ± 0.09X | 0.37 ± 0.09*X |

| CD | 0.22 ± 0.07* | 0.22 ± 0.07X | 0.24 ± 0.07*X | |

| WM | 0.44 ± 0.10*# | 0.42 ± 0.10# | 0.42 ± 0.10* | |

| CM | 0.34 ± 0.11* | 0.34 ± 0.11X | 0.35 ± 0.10*X | |

| F | 0.40 ± 0.09*# | 0.39 ± 0.09# | 0.09* | |

| > 24 km/h | FB | 0.31 ± 0.11# | 0.30 ± 0.11X# | 0.32 ± 0.11X |

| CD | 0.15 ± 0.07* | 0.16 ± 0.08X | 0.17 ± 0.08*X | |

| WM | 0.39 ± 0.14*# | 0.36 ± 0.13# | 0.36 ± 0.13* | |

| CM | 0.21 ± 0.10 | 0.21 ± 0.10 | 0.21 ± 0.09 | |

| F | 0.36 ± 0.14*# | 0.32 ± 0.13# | 0.31 ± 0.13* | |

Statistically significant difference between a win and a loss:

(p ≤ 0.05); between a win and a draw:

(p ≤ 0.05); between a loss and a draw:

(p ≤ 0.05). Playing positions: FB – full-back, CD – central defender, WM – wide midfielder, CM – central midfielder, F – forward.

Distances covered by players at intensities in the 21-23.99 km/h range were significantly shorter among central defenders, full-backs and central midfielders where matches were drawn or won, as opposed to lost (p ≤ 0.05). Furthermore, the wide midfielders and forwards covered significantly longer distances at this speed in won matches, as opposed to drawn and lost ones (p ≤ 0.05) (Table 2).

Finally, where account was taken of distances covered by players at intensities exceeding 24 km/h, it was found that central defenders ran significantly longer distances in lost matches than in ones drawn or won (p ≤ 0.05). Moreover, full-backs covered greater distances at this intensity in lost and won, as compared with drawn matches (p ≤ 0.05). For their part, wide midfielders and forwards covered significantly greater distances at intensity exceeding 24 km/h of speed in won matches than in drawn and lost ones (p ≤ 0.05) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

This study sought to examine how various playing positions and match outcomes (i.e. won, drawn, lost) relate to the total distances covered by soccer players in the Bundesliga, and distances covered at intensities falling within different ranges. The results here in fact represent data unique to the literature, in that they not only relate to a large sample size, but also offer information allowing coaches and training staff to determine minimum levels of physical exertion at various positions that are associated with matches won. The major findings of this study are that won matches differ from those drawn or lost in entailing wide midfielders and forwards running significantly longer distances at intensities in the 21-23.99 km/h range, as well as above 24 km/h. This would appear to confirm the idea that high- or very high-intensity play is a factor relating to the motor preparation of players that can prove crucial in affecting match outcome [5, 13, 15, 17]. However, this is not observed to hold true for all positions on the field, being of particular importance for players with offensive positions such as wide midfielders and forwards. If players in these positions are able to run so far at such speeds, they will be able to execute specific technical and tactical tasks on the pitch. When they are not in possession of the ball, they will often still be engaged in high-intensity activity (high pressing), in attempts to recover a lost ball [15, 41]. While in ball possession, they in turn perform multiple high-intensity activities, such as the receipt of passes and crosses on the run, followed by dribbling within the opponent’s penalty area or shooting at goal [42].

Analysis relating to the activity of full-backs, central defenders and central midfielders in won matches – as opposed to those that were drawn or lost – reveals that players in these positions ran significantly shorter distances at intensity ranges of 17-20.99 and 21-23.99 km/h. This observation may reflect the fact that, when a team is maintaining a favourable result, and especially when the lead over the opponent is of two or more scored goals, then players in defensive positions will be more focused on safeguarding each other and securing against lost goals. The full-backs, central defenders and central midfielders are not forced to engage in offensive actions continuously. To determine why players play differently, we need to study match status. According to Bloomfield et al. [43], Lago and Martin [44] and Taylor et al. [45], the importance of this situational variable is reflected in changes in team and player strategies in response to the evolving score-line. Lago et al. [29] reported that, in elite soccer, players engaged in less high-intensity activity when winning than when losing. A 50% decline in the distance covered at submaximal and maximal intensities (19.1 km/h) when a team is leading suggests that players do not always use their maximal physical capacity for the 90 minutes [29]. In fact, given that winning is a comfortable status for a team, it is also possible that players assume a ball-containment strategy, keeping the game slower, with the result being lower speeds [46]. Accordingly, it is obvious that players may engage in less low-intensity activity when losing than when winning, in an attempt to recover from an unfavourable position [29].

The study also showed that, in won and drawn matches (as opposed to lost ones), players playing in all positions ran significantly greater distances at intensities below 11 km/h. This is consistent with what Andrzejewski et al. [5] noted. Moreover, when a team is winning, its players most often prefer counter-attacking, and thus play on the basis of limited pressing, with their own goal area better secured. In this situation, a winning team must return quickly to the original formation after each offensive action, with this affecting player distance covered at low intensity. This information indicates a need for increased low-intensity mobility of players. As well as consciously applying tactics to not overwork, they restrict distance travelled at medium intensities – a strategy that does not help in the most important situations in the game [29]. Better understanding of such information will thus allow players to save energy for other maximal or submaximal efforts in the course of a game. This may be particularly useful in the second half, when fatigue increases as a match draws to a close, to the point at which actions taken by players are at noticeably reduced intensity [47, 48].

The results detailed here demonstrate that total distances covered and distance covered at various speeds by elite German soccer players in the course of the three domestic seasons from 2014/2015 to 2016/2017 were related closely to match outcome. Wide midfielders and forwards in won matches had covered greater total distances than they had in lost matches. This confirms earlier observations from related studies. Ideally, from the point of view of a win, the greater part of this total distance should be covered at high intensity. Moreover, it was not surprising that the least significant changes in behaviour at different positions between one match outcome or another were to be observed in the medium-intensity ranges. Many studies have reported that the distance covered at medium intensities is not significant where a game’s outcome is concerned [29].

This study did not include physiological parameters, which are very difficult to obtain in a match context. Analysis of kinematic research should ideally be supplemented by data of this kind in the future, as this would certainly enrich our knowledge of the subject. Such information would help identify players’ adaptabilities to specificity of effort in different playing positions, and would allow for more accurate interpretation. Equally, our findings should perhaps be applied with caution to other professional football teams and other strong European leagues, due to the different playing styles characterising different teams, as well as the specific features of different leagues. Future research should also focus on analysis of the best leagues, with information yielded in regard to changes in requirements for individual positions in won matches on a season-by-season basis.

Modern football is very much about the constant effort to discover potential players. The research presented here shows primarily that the best teams should be looking out for, testing and paying attention to transfers of players able to cover long distances at high intensity, or to engage in sustained effort at high intensity, in the offensive positions in particular. This can contribute to success in future matches and competitions. These findings have implications in terms of players’ physical preparation, which could entail individual drills to simulate intense periods of match play whereby tactical and technical aspects are merged with the unique physical demands of each position [1]. Such drills can inter alia include repeated small side games or high-intensity interval exercises increasing players’ speed endurance and glycolytic capacity. Accordingly, the authors in this and related studies have advocated the prescription of additional and/or position-specific high-intensity-type training to respond to the ‘greater’ physical demands required in certain playing positions, and especially among forwards and wide midfielders [7]. Information presented in this study thus has the potential to enhance knowledge of training and competition responses among athletes, coaches, and support staff alike, in this way assisting with the design of improved training and recovery programmes, reducing the incidence of injury or illness, and enhancing performance.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of the present study emphasise the importance of considering match outcome and playing position as physical aspects of soccer performance are assessed. In won matches, as opposed to drawn or lost matches, the wide midfielders and forwards ran a significantly longer distance at the 21-23.99 and >24 km/h ranges of intensity. Furthermore, the full-backs, central defenders and central midfielders in won matches (as opposed to those drawn or lost) ran significantly less far at intensities in the 17-20.99 and 21-23.99 km/h ranges. Researchers should thus account for match outcome and playing positions in their explanatory models, in order to better understand why physical demands vary throughout the game. Consequently, assessments of the technical, tactical, and physical aspects of performance can be made more objective by factoring in the effects of match outcome. Finally, coaches should consider these arrangements as they introduce additional specific drills for players playing in different positions and engage in further-reaching individualisation, with more time devoted to training-load customisation.

Conflict of interests

the authors declared no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bush M, Barnes C, Archer DT, Hogg B, Bradley PS. Evolution of match performance parameters for various playing positions in the English Premier League. Hum Mov Sci. 2015;39:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradley PS, Archer DT, Hogg B, Schuth G, Bush M, Carling C, Barnes C. Tier-specific evolution of match performance characteristics in the English Premier League: It’s getting tougher at the top. J Sports Sci. 2016;34:980–987. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2015.1082614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ade JD, Harley JA, Bradley PS. Physiological response, time– motion characteristics, and reproducibility of various speed-endurance drills in elite youth soccer players: Small-sided games versus generic running. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2014;9:471–479. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2013-0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carling C, Bloomfield J, Nelsen L, Reilly T. The role of motion analysis in elite soccer: contemporary performance measurement techniques and work rate data. Sports Med. 2008;38:839–862. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200838100-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrzejewski M, Konefał M, Chmura P, Kowalczuk E, Chmura J. Match outcome and distances covered at various speeds in match play by elite German soccer players. Int J Perform Anal Sport. 2016;16:818–829. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abt G, Lovell R. The use of individualized speed and intensity thresholds for determining the distance run at high-intensity in professional soccer. J Sports Sci. 2009;27:893–898. doi: 10.1080/02640410902998239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carling C. Interpreting physical performance in professional soccer match-play: should we be more pragmatic in our approach? Sports Med. 2013;43:655–663. doi: 10.1007/s40279-013-0055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andrzejewski M, Chmura J, Pluta B, Strzelczyk R, Kasprzak A. Analysis of sprinting activities of professional soccer players. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27:2134–2140. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318279423e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Konefał M, Chmura P, Andrzejewski M, Pukszta D, Chmura J. Analysis of match performance of full-backs from selected European soccer leagues. Cent Eur J Sport Sci Med. 2015;11:45–53. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castellano J, Alvarez-Pastor D, Bradley PS. Evaluation of research using computerised tracking systems (Amisco and Prozone) to analyse physical performance in elite soccer: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2014;44:701–712. doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0144-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoppe MW, Slomka M, Baumgart C, Weber H, Freiwald J. Match Running Performance and Success Across a Season in German Bundesliga Soccer Teams. Int J Sports Med. 2015;36:563–566. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1398578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bangsbo J, Mohr M, Krustrup P. Physical and metabolic demands of training and match-play in the elite football player. J Sports Sci. 2006;24:665–674. doi: 10.1080/02640410500482529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrzejewski M, Chmura P, Konefał M, Kowalczuk E, Chmura J. Match outcome and sprinting activities in match play by elite German soccer players. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2017 doi: 10.23736/S0022-4707.17.07352-2. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bloomfield J, Polman R, O’Donoghue P. Physical Demands of Different Positions in FA Premier League Soccer. J Sports Sci Med. 2007;6:63–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dellal A, Chamari K, Wong DP, Ahmaidi S, Keller D, Barros R, Bisciotti GN. Comparison of physical and technical performance in European soccer match-play. Eur J Sport Sci. 2011;11:51–59. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krustrup P, Mohr M, Ellingsgaard H, Bangsbo J. Physical demands during an elite female soccer game: importance of training status. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37:1242–1248. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000170062.73981.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chmura P, Andrzejewski M, Konefal M, Mroczek D, Rokita A, Chmura J. Analysis of Motor Activities of Professional Soccer Players during the 2014 World Cup in Brazil. J Hum Kinet. 2017;56:187–195. doi: 10.1515/hukin-2017-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stolen T, Chamari K, Castagna C. Physiology of soccer: an update. Sports Med. 2005;35:501–36. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200535060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Djaoui L, Wong DP, Pialoux V, Hautier C, Da Silva CD, Chamari K, Dellal A. Physical Activity during a Prolonged Congested Period in a Top-Class European Football Team. Asian J Sports Med. 2014;5:47–53. doi: 10.5812/asjsm.34233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradley PS, Carling C, Archer D, Roberts J, Dodds A, Di Mascio M, Paul D, Diaz AG, Peart D, Krustrup P. The effect of playing formation on high-intensity running and technical profiles in English FA Premier League soccer matches. J Sports Sci. 2011;29:821–830. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2011.561868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lago-Ballesteros J, Lago-Peñas C. Performance in Team Sports: Identifying the Keys to Success in Soccer. J Hum Kinet. 2010;25:85–91. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oberstone J. Differentiating the Top English Premier League Football Clubs from the Rest of the Pack: Identifying the Keys to Success. J Quant Anal Sports. 2009;5:1183–1200. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tenga A, Sigmundstad E. Characteristics of goal-scoring possessions in open play: Comparing the top, in-between and bottom teams from professional soccer league. Int J Perform Anal Sport. 2011;11:545–552. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rampinini E, Impellizzeri FM, Castagna C, Coutts AJ, Wisløff U. Technical performance during soccer matches of the Italian Serie A league: Effect of fatigue and competitive level. J Sci Med Sport. 2009;12:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor JB, Mellalieu SD, James N. A Comparison of Individual and Unit Tactical Behaviour and Team Strategy in Professional Soccer. Int J Perform Anal Sport. 2005;5:87–101. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tenga A, Holme I, Ronglan L, Bahr R. Effect of playing tactics on goal scoring in Norwegian professional soccer. J Sports Sci. 2010;28:237–244. doi: 10.1080/02640410903502774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carling C. Analysis of physical activity profiles when running with the ball in a professional soccer team. J Sports Sci. 2010;28:319–326. doi: 10.1080/02640410903473851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gregson W, Drust B, Atkinson G, Salvo V. Match-to-match variability of high-speed activities in premier league soccer. Int J Sports Med. 2010;31:237–242. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lago C, Casais L, Dominguez E, Sampaio J. The effects of situational variables on distance covered at various speeds in elite soccer. Eur J Sport Sci. 2010;10:103–109. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor JB, Mellalieu SD, James N, Barter P. Situation variable effects and tactical performance in professional association football. Int J Perform Anal Sport. 2010;10:255–269. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Travassos B, Davids K, Araújo D, Pedro Esteves T. Performance analysis in team sports: Advances from an Ecological Dynamics approach. Int J Perform Anal Sport. 2013;13:83–95. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rampinini E, Bishop D, Marcora SM, Ferrari Bravo D, Sassi R, Impellizzeri FM. Validity of simple field tests as indicators of match-related physical performance in top-level professional soccer players. Int J Sports Med. 2006;28:228–235. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tiedemann T, Francksen T, Latacz-Lohmann U. Assessing the performance of German Bundesliga football players: a non-parametric metafrontier approach. Cent Eur J Oper Res. 2010;19:571–587. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Link D, Weber H. Effect of Ambient Temperature on Pacing in Soccer depends on Skill Level. J Strength Cond Res. 2017;31:1766–1770. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000001013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leser R, Baca A, Ogris G. Local positioning systems in (game) sports. Sensors. 2011;11:9778–9797. doi: 10.3390/s111009778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stulp G, Kordsmeyer T, Buunk AP, Verhulst S. Increased aggression during human group contests when competitive ability is more similar. Biol Lett. 2012;8:921–923. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2012.0591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siegle M, Stevens T, Lames M. Design of an accuracy study for position detection in football. J Sports Sci. 2013;31:166–172. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2012.723131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coutts AJ, Quinn J, Hocking J, Castagna C, Rampinini E. Match running performance in elite Australian Rules Football. J Sci Med Sport. 2010;13:543–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carling C, Dupont G. Are declines in physical performance associated with a reduction in skill-related performance during professional soccer match-play? J Sports Sci. 2011;29:63–71. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2010.521945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chmura P, Konefał M, Kowalczuk E, Andrzejewski M, Rokita A, Chmura J. Distances covered above and below the anaerobic threshold by professional football players in different competitive conditions. Cent Eur J Sport Sci Med. 2015;10:25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dellal A, Wong DP, Moalla W, Chamari K. Physical and technical activity of soccer players in the French First League – with special reference to their playing position. Int J Sports Med. 2010;11:278–290. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andrzejewski M, Chmura J, Pluta B. Analysis of motor and technical activities of professional soccer players of the UEFA Europa League. Int J Perform Anal Sport. 2014;14:504–523. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bloomfield JR, Polman RCJ, O’Donoghue PG. Effects of score-line on team strategies in FA Premier League soccer. J Sports Sci. 2005;23:192–193. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lago C, Martin R. Determinants of possession of the ball in soccer. J Sports Sci. 2007;25:969–974. doi: 10.1080/02640410600944626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taylor JB, Mellalieu SD, James N, Shearer D. The influence of match location, qualify of opposition and match status on technical performance in professional association football. J Sports Sci. 2008;26:885–895. doi: 10.1080/02640410701836887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bloomfield JR, Polman RCJ, O’Donoghue PG. Effects of score-line on intensity of play in midfield and forward players in the FA Premier League. J Sports Sci. 2005;23:191–192. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Castellano J, Blanco-Villaseñor A, Alvarez D. Contextual variables and time-motion analysis in soccer. Int J Sports Med. 2011;32:415–421. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1271771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mugglestone C, Morris JG, Saunders B, Sunderland C. Half-time and high-speed running in the second half of soccer. Int J Sports Med. 2013;34:514–519. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1327647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]