Abstract

Objectives

The detection of autoantibodies to the muscarinic receptor type 3 (M3R) in the serum of patients with Sjögrens syndrome (SS) by ELISA is controversial. A study was undertaken to test whether modification of M3R peptides could enhance the antigenicity and increase the detection of specific antibodies using an ELISA.

Methods

A series of controlled ELISAs was performed with serum from 71 patients with SS and 37 healthy volunteers (HV) on linear, citrullinated and/or cyclised and multi-antigenic peptides (MAP) of the three extracellular M3R loops to detect specific binding.

Results

Significant differences (p<0.05) in optical density (OD) between serum from patients and HV were detected for a cyclised loop 1-derived peptide and the negative control peptide. Furthermore, there were no statistically significant differences between the frequency of positive patients (defined as OD >2SDs above the mean of the HV) and HV on any of the peptides tested.

Conclusions

Binding of serum from patients with SS to M3R-derived peptides does not differ from binding to a control peptide in an ELISA and no significant binding to M3R-derived peptides was found in the serum from individual patients compared with HV. These data suggest that peptide-based ELISAs are not sufficiently sensitive and/or specific to detect anti-MR3 autoantibodies.

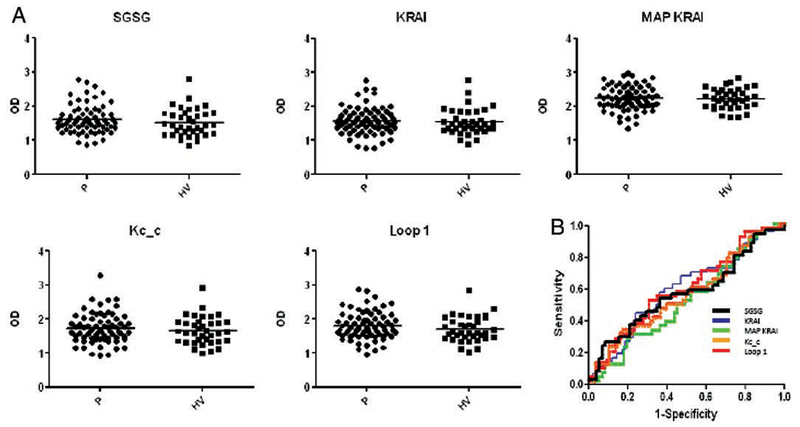

The frequency of patients positive for muscarinic receptor type 3 (M3R) autoantibodies, thought to be a key pathogenic factor in the exocrine dysfunction in patients with Sjögrens syndrome (SS),1 is reported to vary from 0% up to nearly 100% when detected by a linear peptide-based ELISA.2–6 Low anti-M3R titres, the inability of an antibody to recognise a linear peptide and/or the choice of epitope may all have a role in the variability observed. We tested sera from patients with SS and healthy volunteers (HV) on previously reported M3R peptides, as well as on cyclised, citrullinated7 and multi-antigenic peptide (MAP) versions.8 Serum from 79 patients (primary SS,9 mean age 49.5 years, 89% women) and 37 HV (mean age 45.5, 67% women) was obtained at our clinic and at the NIH blood bank and stored at −80°C until use. Several ELISA conditions were tested and optimised using a MAP-8 Ro peptide (LQEMPLTALLRNLGKMT). Ten M3R-derived peptides (three linear loop 2 peptides, three cyclised loop 1, 2 or 3 peptides, two MAP-8 loop 2 peptides, one citrullinated loop 2 and one citrullinated and cyclised loop 2) and a SGSG control peptide were screened in a series of pilot ELISAs with 15 HV and 37 patients to determine the most antigenic peptides. Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) graphs were made and the area under the curve (AUC) was determined for each peptide (data not shown). Four peptides were chosen based on their highest average AUC: KRAI (AUC 0.714), MAP KRAI (AUC 0.662), Kc_c (AUC 0.751) and loop 1 (AUC 0.680) (for sequence see figure 1). These and the control SGSG peptide were reassayed in four tightly controlled ELISAs on four consecutive days with serum from all patients and HV (figure 1A). The analysis of variance results showed that the between-day variation in optical density (OD) scores was significant for all peptides (p≤0.002) except the SGSG peptide (p=0.207). Significant differences between HV and patients were found for the SGSG (p=0.037) and the loop 1 peptide (p=0.025). To determine sensitivity and specificity of each peptide, ROC graphs were made and the AUC was calculated (figure 1B). None of the AUC were statistically significant (p>0.100). Individual autoantibody positivity was defined as an average OD >2SD of the mean of the HV, assuming a normal distribution in this group (table 1).

Figure 1.

(A) Dot plots of 4-day average optical density (OD) in peptide ELISAs for each patient (P) and healthy volunteer (HV). Control peptides SGSG (SGSGSGSGSGSGSGSG), extracellular (EC) loop 2-derived KRAI (KRTVPPGECFIQFLSEPTITFGTAI), MAP KRAI (MAP-8, sequence KRAI; Facility for Biotechnology Resources at the NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, USA), Kc_c (CFVGKCitrullineTVPPGEC cyclised; Washington Biotechnology, Columbia, Maryland, USA) and EC loop 1 (TTYIIMNRWALGNLACdC cyclised; NIH), all HPLC purified, were incubated overnight at 10 μg/ml peptide in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 4°C in a 96-well plates (NUNC, Maxisorp). The next day plates were washed (PBS+0.05% Tween 20) and blocked for 2 h (reagent diluent; R&D, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA). After washing, one aliquot of prediluted (1:100 in reagent diluent) frozen (−80°C) serum for each individual was thawed and added to each well in duplicate for 2 h, with the patients and HV randomly placed. After washing, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antihuman IgG (GTX 26759 Genetex) was added (1:10 000/100 μl/well) for 1 h. Plates were washed and 100 μl of substrate reagent (R&D) was added for 10 min and stopped with stop solution (50 per well; R&D). Plates were read at 450 nm on a spectramax plate reader (maximum OD 4.0). The ELISA was repeated on four consecutive days in exactly the same way. Results are displayed as individual average OD after subtraction of the blank. (B) Receiver operating characteristics curves for the four peptides and the control peptides were made using SAS 9.2 software to determine sensitivity and specificity of the tested peptides. The results of the 4-day average are shown in an overlapping graph.

Table 1.

Percentage of healthy volunteers (HV) and patients (P) with an average optical density (OD) >2SDs above the mean of the HV

| Peptide | HV, % of group (n) | P, % of group (n) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SGSG | 2.7 (1) | 9.9 (7) | 0.178 |

| KRAI | 5.4 (2) | 7.0 (5) | 0.743 |

| MAP KRAI | 2.7 (1) | 7.0 (5) | 0.350 |

| Kc_c | 2.7 (1) | 5.6 (4) | 0.492 |

| Loop 1 | 2.7(1) | 4.2 (3) | 0.691 |

The p values represent the significance of the corresponding two-independent sample χ2 test.

The present study demonstrates a poor reproducibility of M3R peptide-based ELISAs. The average patient OD of loop 1 was significantly different from the HV, but this was also observed with the SGSG peptide, and there were no differences in the number of positive individuals between the two groups.

There are some technical reasons that may account for these negative results, including microstructural changes in the tested peptides over time and inconsistency in binding of the peptide to the microtitre plate. Other reasons may be that M3R autoantibodies are reactive with other non-tested epitopes, only recognise an epitope in its native form or peptide:antibody interactions may be too weak/unstable. Moreover, the lack of a reliable positive control may have limited our efforts to optimise conditions for M3R antibodies.

Our data indicate that relatively simple peptide-based ELISAs are not sufficiently sensitive and specific to detect the putative anti-M3R autoantibodies. Functional assays using native receptors are more elaborate but may prove more reliable.10,11 Future studies should therefore use controls which have tested positive in functional assays. Establishing a reference set of such sera which could be shared among investigators would significantly aid in clarifying the controversies about the detection of anti-M3R antibodies.

Acknowledgments

Funding This research was supported by the intramural research program of the NIH, NIDCR.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Ethics approval All subjects signed an informed consent and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the National Institutes of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR).

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dawson L, Tobin A, Smith P, et al. Antimuscarinic antibodies in Sjögren’s syndrome: where are we, and where are we going? Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:2984–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naito Y, Matsumoto I, Wakamatsu E, et al. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor autoantibodies in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:510–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kovács L, Marczinovits I, György A, et al. Clinical associations of autoantibodies to human muscarinic acetylcholine receptor 3(213-228) in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:1021–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavill D, Waterman SA, Gordon TP Failure to detect antibodies to extracellular loop peptides of the muscarinic M3 receptor in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. J Rheumatol 2002;29:1342–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zigon P, Bozic B, Cucnik S, et al. Are autoantibodies against a 25-mer synthetic peptide of M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor a new diagnostic marker for Sjögren’s syndrome? Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:1247; author reply 1247. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura Y, Wakamatsu E, Matsumoto I, et al. High prevalence of autoantibodies to muscarinic-3 acetylcholine receptor in patients with juvenile-onset Sjögren syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:136–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schellekens GA, Visser H, de Jong BA, et al. The diagnostic properties of rheumatoid arthritis antibodies recognizing a cyclic citrullinated peptide. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:155–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tam JP, Zavala F. Multiple antigen peptide. A novel approach to increase detection sensitivity of synthetic peptides in solid-phase immunoassays. J Immunol Methods 1989;124:53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Jonsson R, et al. ; European Study Group on Classification Criteria for Sjögren’s Syndrome. Classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:554–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waterman SA, Gordon TP Rischmueller M. Inhibitory effects of muscarinic receptor autoantibodies on parasympathetic neurotransmission in Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:1647–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dawson LJ, Stanbury J, Venn N, et al. Antimuscarinic antibodies in primary Sjögren’s syndrome reversibly inhibit the mechanism of fluid secretion by human submandibular salivary acinar cells. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:1165–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]