Abstract

Background

Infections caused by vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) are on the rise worldwide. Few studies have tried to estimate the mortality burden as well as the financial burden of those infections and found that VRE are associated with increased mortality and higher hospital costs. However, it is unclear whether these worse outcomes are attributable to vancomycin resistance only or whether the enterococcal species (Enterococcus faecium or Enterococcus faecalis) play an important role. We therefore aimed to determine the burden of enterococci infections attributable to vancomycin resistance and pathogen species (E. faecium and E. faecalis) in cases of bloodstream infection (BSI).

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study on patients with BSI caused by Enterococcus faecium or Enterococcus faecalis between 2008 and 2015 in three tertiary care hospitals. Data was collected on true hospital costs (in €), length of stay (LOS), basic demographic parameters, and underlying diseases including the results of the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI). We used univariate and multivariable regression analyses to compare risk factors for in-hospital mortality and length of stay (i) between vancomycin-susceptible E. faecium- (VSEm) and vancomycin-susceptible E. faecalis- (VSEf) cases and (ii) between vancomycin-susceptible E. faecium- (VSEm) and vancomycin-resistant E. faecium-cases (VREm). We calculated total hospital costs for VSEm, VSEf and VREm.

Results

Overall, we identified 1160 consecutive cases of BSI caused by enterococci: 596 (51.4%) cases of E. faecium BSI and 564 (48.6%) cases of E. faecalis BSI. 103 cases of E. faecium BSI (17.3%) and 1 case of E. faecalis BSI (0.2%) were infected by vancomycin-resistant isolates. Multivariable analyses revealed (i) that in addition to different underlying diseases E. faecium was an independent risk factor for in-hospital mortality and prolonged hospital stay and (ii) that vancomycin-resistance did not further increase the risk for the described outcomes among E. faecium-isolates. However, the overall hospital costs were significantly higher in VREm-BSI cases as compared to VSEm- and VSEf-BSI cases (80,465€ vs. 51,365€ vs. 31,122€ p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Our data indicates that in-hospital mortality and infection-attributed hospital stay in enterococci BSI might rather be influenced by Enterococcus species and underlying diseases than by vancomycin resistance. Therefore, future studies should consider adjusting for Enterococcus species in addition to vancomycin resistance in order to provide a conservative estimate for the burden of VRE infections.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13756-018-0419-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Bloodstream infection, Vancomycin-resistant enterococci, Enterococcus faecium

Introduction

Enterococcus spp. are part of the normal gastrointestinal flora. Among those pathogens, resistance to antimicrobial substances, notably to vancomycin, results in limited therapeutic options [1, 2]. In recent years, hospital-acquired infections (HAI) caused by vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) have emerged as a relevant burden on patients and healthcare systems globally [3–5]. In order to reduce the spread of resistant strains in hospitals, infection control measures, e.g. contact precautions, have been proposed [6, 7]. To assess the efficiency of VRE prevention measures, the mortality- and financial burden of VRE infections has to be assessed. However, the methodological approach on assessing VRE-burden remains controversial [2, 8, 9] and only few studies have addressed economic aspects [10–15]. As costs are often not available as infection-attributable costs (costs after onset for infection) length of stay (LOS) after onset of infection is being used as a surrogate parameter [2, 8, 16].

Although analyses should compare VRE infections to VSE-infected patients when the attributable effect of vancomycin resistance is addressed, [2, 8, 16] prior studies also utilized comparisons to cohorts with non-enterococcus infections [17, 18] or cohorts without infection [8, 12, 19–24]. Since the course of enterococcal infections may also be influenced by the enterococcus subspecies itself [2, 8, 9, 25, 26], analyses not considering the pathogen species may therefore be biased as result of the different virulence of the pathogens.

In a large cohort of cases with bloodstream infection (BSI), we therefore studied the influence of vancomycin resistance and enterococcus subspecies on in-hospital mortality, hospital costs and length of hospital stay.

Methods

Setting, study design and data collection

The study was conducted at three different tertiary care hospitals of the Charité university hospital in Berlin, with 3011-beds in total [27]. After a confirmatory ethics vote was obtained from the Charité University Medicine ethics committee (internal processing key EA4/229/17), we performed a cohort study that included all cases of BSI caused by Enterococcus faecalis or Enterococcus faecium between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2015. Cases were identified in the Charité microbiology database as hospitalized patients with blood cultures positive for one of these pathogens. Data on costs and hospital financial accounting was provided by the Charité Department of Financial Controlling as true hospital expenses in Euros. For all patients enrolled in this study, the following demographic and clinical characteristics were collected: age, sex, in-hospital death, length of hospital stay (LOS), day of BSI onset and stay on an intensive care unit (days). Length of stay in total and after BSI onset were defined as length of stay until death or discharge. The Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) was obtained on the basis of the patients’ diagnosed comorbidities using the method of Charlson et al. and the adaptation for the ICD-10 by Thygesen et al. [28, 29]. The original 17 Charlson comorbidity categories were cumulated based on the affected organ system in the following ten disease categories: heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, neurologic disease, lung disease, rheumatic disease, gastrointestinal disease, liver disease, diabetes, renal disease and cancer/immunological disease.

Definitions and statistical methods

Cases were defined as patients with BSI caused by Enterococcus spp. (Enterococcus faecalis or Enterococcus faecium) during the study period. Each patient was included in the analysis once. Onset of BSI was defined as the date of the first blood culture positive for the respective pathogen. BSI was considered hospital-onset if it occurred after the third day of hospitalization. Mortality was assessed based on discharge alive or in-hospital death. Data on hospital costs were derived from true hospital costs (hospital expenses). The costs analyzed cover direct costs to the hospital of treatment and diagnostics as well as indirect hospital costs of activities without patient contact (e.g. administration, hospital maintenance). The estimated cost of individual cases was based on definite performances and on settlement keys (e.g. nurse working time per patient). Economic data was available on total hospital costs and on daily costs. A differentiation of costs before and after the infection was not available. However, as length of stay directly correlates with hospital costs, length of stay after onset for infection can be applied as proxy for infection attributable additional expenditures [2, 30, 31]. We therefore assessed the multiplicative effect on length of stay after BSI onset in a multivariable linear regression.

Descriptive, univariate analyses were performed for the total cohort, stratified by enterococcus species (i.e. vancomycin susceptible E. faecium vs. vancomycin susceptible E. faecalis) and by vancomycin susceptibility (i.e. vancomycin susceptible enterococci vs. vancomycin resistant enterococci). Since among E. faecalis-isolates only one isolate was resistant against vancomycin, only E. faecium (VSEm vs. VREm) were analyzed in the second analysis. Additionally, we compared in univariate analysis deceased patients and patients discharged alive. The median and the interquartile range (IQR) were calculated for continuous parameters; number and percentage were calculated for binary parameters. Univariate differences were tested using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and the Chi-square test for binary variables.

The two linear regression analyses were performed for length of stay (LOS) after onset of enterococcal BSI by stepwise forward variable selection. The continuous parameters LOS after onset of BSI was log transformed to achieve normal distribution. Only surviving patients were included. Parameters considered in the full model were vancomycin resistance OR pathogen species (E. faecium or E. faecalis), sex, age and all underlying diseases assessed as described above. From the full model, parameters with the smallest Chi-square statistic and p > 0.05 in the type III test were removed. The regression coefficients were converted to the measures of effect using an exponential transformation and referred to as the multiplicative effect (ME) of investigated parameters. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Multivariable, binary logistic regression was performed for in-hospital death by stepwise forward selection. The p-values for including a variable in the model was 0.05 and for excluding 0.06 respectively. Odds ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated. Parameters considered in the model were sex, age, pathogen species (E. faecium vs. E. faecalis) with the interaction of the vancomycin resistance and all underlying diseases assessed as described above.

All analyses were performed using SPSS (IBM SPSS statistics, Somer, NY, USA) and SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Microbiological methods

If a blood stream infection was suspected, blood cultures were drawn and incubated for up to seven days using standard blood culture tubes (BACTEC, Becton Dickinson Heidelberg Germany). If growth was detected, gram staining and culturing were performed. MALDI TOF MS and Vitek 2 automated system (Biomerieux Marcy l’etoile France) were used for identification and susceptibility testing of bacterial strains. They were interpreted using EUCAST definitions.

Results

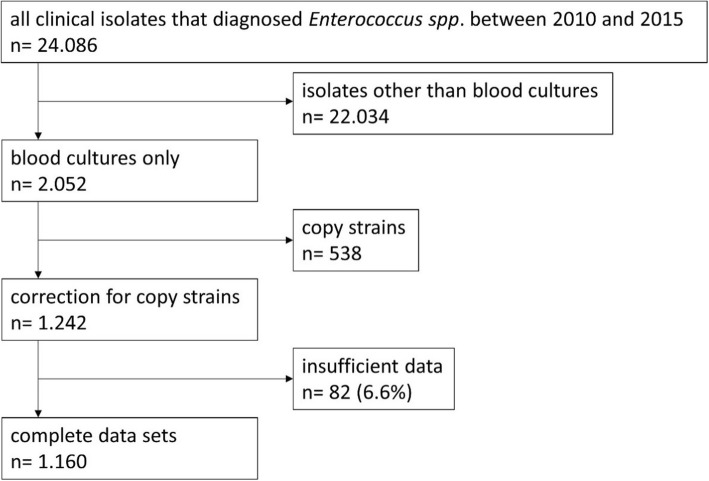

We initially extracted n = 24,086 clinical isolates diagnosed with Enterococcus faecium or Enterococcus faecalis from the microbiology database. After excluding all isolates not derived from blood cultures and correcting for copy strains, 1242 patients with BSI caused by E. faecium or E. faecalis were included in the analysis (Fig. 1). Sufficient data on all relevant parameters was available for 96.4% of the patients. Overall, this accounted for 1160 patients, 91% with infections caused by VSE and 9% by VRE. Table 1 gives an overview of the parameters for all patients and shows the results of the (i) univariate comparison of VSEm vs. VSEf and (ii) the comparison of VSEm vs. VREm BSI cases. The highest in-hospital mortality rate was found among VREm cases (50.5%) followed by VSEm cases (39.6%) and VSEf cases (24.4%). Also regarding LOS, highest numbers were found among VREm cases (total LOS, 54 days) followed by VSEm (42 days) and VSEf (32 days). In all three groups, the Charlson comorbidity score was similar with a median of 7.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart depicting patient recruitment based on blood culture isolates

Table 1.

Univariate analysis of epidemiologic parameters, length of stay, and direct hospital costs of cases with blood stream infection caused by enterococcus spp. stratified by vancomycin resistance

| Parameter | (A) VS-E. faecium (n = 493) | (B) VS-E. faecalis (n = 563) | P-Value for A) vs. B) | (C) VR-E. faecium (n = 103) | P-Value for C) vs. A) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-Value | OR (CI 95) | P-Value | OR (CI 95) | ||||

| In-hospital mortality | 39.6% (195) | 24.4% (132) | 0.000 | 2.137 (1.638-2.787) | 50.5% (52) | 0.041 | 1.558 (1.017–2.387) |

| Male | 58.6% (289) | 63.1% (355) | 0.141 | 0.830 (0.648-1.063) | 66.0% (68) | 0.163 | 1.371 (0.879–2.141) |

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 67 (54–75) | 64 (53–73) | 0.059 | n.a. | 61 (52–70) | 0.107 | |

| Cardiac disease | 28.2% (139) | 29.0% (163) | 0.786 | 0.964 (0.737-1.259) | 26.2% (27) | 0.683 | 0.905 (0.559-1.464) |

| Vascular disease | 22.1% (109) | 22.4% (126) | 0.916 | 0.984 (0.736-1.317) | 22.3% (23) | 0.961 | 1.013 (0.608-1.687) |

| Pulmonary disease | 20.1% (99) | 23.1% (130) | 0.236 | 0.837 (0.623-1.124) | 21.4% (22) | 0.769 | 1.081 (0.643-1.818) |

| Rheumatic disease | 3.0% (15) | 3.6% (20) | 0.644 | 0.852 (0.431-1.683) | 2.9% (3) | 0.944 | 0.956 (0.272-3.364) |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 5.5% (27) | 3.7% (21) | 0.174 | 1.495 (0.834-2.680) | 5.8% (6) | 0.888 | 1.068 (0.429-2.656) |

| Diabetes | 22.9% (113) | 32.0% (180) | 0.001 | 0,633 (0,481-0,833) | 19.4% (20) | 0.437 | 0,810 (0.476-1.379) |

| Renal disease | 59.0% (291) | 52.8% (297) | 0.041 | 1.290 (1.011-1.647) | 70.9% (73) | 0.025 | 1.689 (1.065-2.679) |

| Liver disease | 29.6% (146) | 19.9% (112) | 0.000 | 1.694 (1.276-2.249) | 42.7% (44) | 0.009 | 1.772 (1.146-2,74) |

| Cancer/ immunological disease | 48.1% (237) | 36.1% (203) | 0.000 | 1.642 (1.283-2.101) | 53.4% (55) | 0.325 | 1.238 (0.809-1.894) |

| Neurological disease | 7.3% (36) | 13.0% (73) | 0.003 | 0,529 (0,348-0,804) | 8.7% (9) | 0.616 | 1.215 (0.566-2.608) |

| Charlson comorbidity index, median (IQR) | 7 (4–9) | 7 (4–9) | 0.907 | n.a. | 7 (5–9) | 0.377 | n.a. |

| Length of stay as Median (IQR) | |||||||

| LOS total (days) | 42 (23–78) | 32 (16–61) | 0.000 | n.a. | 54 (36–85) | 0.010 | n.a. |

| LOS before BSI (days) | 19 (9–34) | 10 (2–25) | 0.000 | n.a. | 27 (15–39) | 0.003 | n.a. |

| LOS after BSI (days) | 18 (8–41) | 16 (8–33) | 0.308 | n.a. | 23 (8–45) | 0.183 | n.a. |

| LOS normal ward | 15 (1–36) | 11 (1–25) | 0.010 | n.a. | 17 (0–44) | 0.368 | n.a. |

| LOS ICU | 18 (1–49) | 10 (1–40) | 0.016 | n.a. | 24 (5–57) | 0.050 | n.a. |

| Hospital costs as median (IQR) | |||||||

| Total hospital costs | 51,365 (22,535-119,789) | 31,122 (11,829-74,344) | 0.000 | n.a. | 80,465 (47,887–157,447) | 0.000 | n.a. |

| Daily costs | 1,237 (729–1,812) | 1,014 (614–1,466) | 0.000 | n.a. | 1,484 (1,095–2,186) | 0.000 | n.a. |

| Medical staff | 7,600 (3169-16,468) | 5,344 (1841-12,213) | 0.000 | n.a. | 10,390 (6,364–20,983) | 0.002 | n.a. |

| Nursing staff | 11,499 (4,476-26,237) | 7,141 (2,610-21,591) | 0.000 | n.a. | 16,661 (8,029–32,905) | 0.003 | n.a. |

| Assistant medical technicians | 2,630 (1,028-5694) | 1,906 (646–4,325) | 0.000 | n.a. | 3,665 (1,397–6,795) | 0.082 | n.a. |

| Pharmacy | 6,924 (2,200-20,922) | 2,742 (636–7,865) | 0.000 | n.a. | 17,145 (8,087–36,779) | 0.000 | n.a. |

| Expenses for implants/transplants | 0 (0–412) | 0 (0–170) | 0.005 | n.a. | 20 (0–605) | 0.767 | n.a. |

| Medical supply | 6,858 (2,820-15,057) | 3,926 (− 1,338-9,782) | 0.000 | n.a. | 9,878 (5,104–18,957) | 0.002 | n.a. |

| Medical infrastructure | 1,893 (939–4,128) | 1,473 (547–3,271) | 0.000 | n.a. | 2,629 (1,611–5,219) | 0.001 | n.a. |

| Non-medical infrastructure | 8,975 (4,215-18,206) | 6,176 (2,576-14,049) | 0.000 | n.a. | 12,244 (6,763–20,002) | 0.003 | n.a. |

Categorical variables displayed as percentage and number; continuous variable displayed as median and interquartile range. *P-value, categorical variables tested with Chi-square test, continuous variable tested with Wilcoxon rank sum test. BSI = blood stream infection, IQR = interquartile range, OR = odds ratio, CI95 = 95% confidence interval. VRE = vancomycin-resistant enterococcus, VSE = vancomycin-susceptible enterococcus. N.a. = not applicable

Bold entries represent statistically significant factors

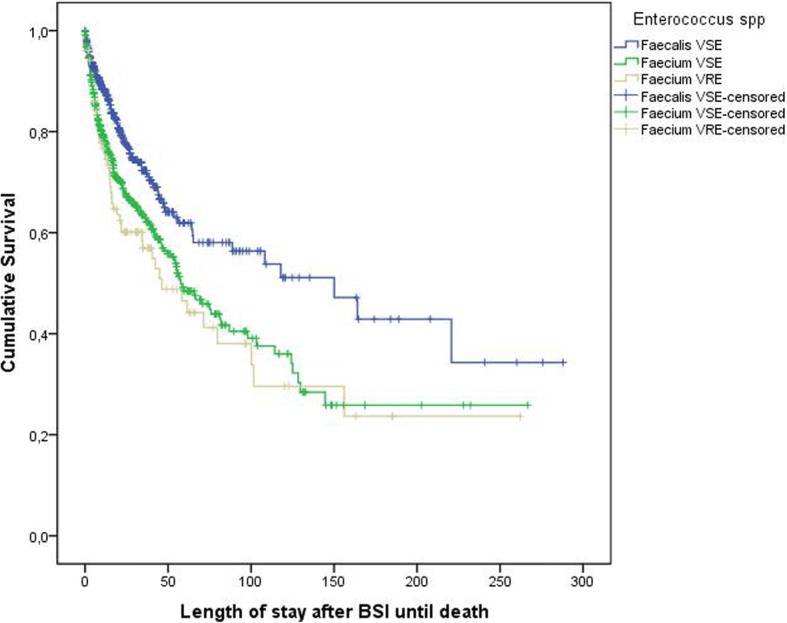

In multivariable analyses on LOS after BSI onset among vancomycin-susceptible enterococci cases, some chronic diseases and E. faecium statistically significant increased LOS as compared to E. faecalis (see Table 2). Vancomycin-resistance was not found to additionally increase LOS among E. faecium cases (see Table 2 and Fig. 2). Regarding in-hospital death, patients with E. faecium-BSI had a higher chance for death as compared to E. faecalis-cases when only vancomycin-susceptible cases were considered (see Table 3 and 4). Among E. faecium cases, vancomycin-resistant was not found to be an additional risk factor for death (Table 4).

Table 2.

Multivariable linear regression on length of stay of surviving patients after BSI onset

| Parameter | VS-E. faecium vs. VS-E. faecalis | VS-E. faecium vs. VR-E. faecium | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ME | Sig. | CI 95 (lower-upper) | ME | Sig. | CI 95 (lower-upper) | ||||||

| Renal Disease | 1.588 | 0000 | 1.891 | – | 3.868 | 1516 | 0.001 | 1.472 | – | 4.201 | |

| Age (years) | 0.659 | 0000 | 0.969 | – | 0.987 | Not significant | |||||

| Lung Disease | 1.457 | 0000 | 1.800 | – | 4.342 | 1333 | 0.018 | 1.151 | – | 4.409 | |

| Gastrointestinal Disease | 1.323 | 0001 | 1.959 | – | 11.025 | Not significant | |||||

| Liver Disease | 1.270 | 0.003 | 1.256 | – | 3.100 | 1370 | 0.009 | 1.226 | – | 4.155 | |

| Vascular Disease | 1.216 | 0.016 | 1.104 | – | 2.622 | Not significant | |||||

| Enterococcus species | E. faecium | 1.258 | 0.004 | 1.170 | – | 2.324 | Not applicable | ||||

| E. faecalis | Reference = 1 | ||||||||||

BSI = bloodstream infection, CI95 = 95% confidence interval, ME multiplicative effect

Fig. 2.

Kaplan Meier survival curve of patients with enterococcal blood stream infection (BSI). VSE, vancomycin-resistant enterococcus. VRE, vancomycin-susceptible enterococcus. Censored = left the hospital alive

Table 3.

Univariate analysis on risk factors for in-hospital death

| Parameter | Discharge alive (n = 781) | In-hospital death (n = 379) | *P-value | OR (CI 95) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vancomycin resistance | 6.7% (52) | 13.7% (52) | < 0.001 | 2.273 (1.512-3.417) |

| E. faecium | 44.7% (349) | 65.2% (247) | < 0.001 | 2.311 (1.792-2.979) |

| E. faecalis | 55.3% (432) | 34.8% (132) | 1 = Reference | |

| Male | 61.2% (478) | 62.0% (235) | 0.792 | 1.037 (0.805-1.334) |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 64.0 (51–73) | 66.0 (56–74) | 0.011 | n.a. |

| Heart disease | 25.1% (196) | 35.4% (134) | < 0.001 | 1.641 (1.258-2.14) |

| Vascular disease | 19.6% (153) | 27.7% (105) | 0.002 | 1,57 (1,18-2.091) |

| Lung disease | 19.6% (153) | 26.1% (99) | 0.011 | 1.461 (1.093-1.952) |

| Rheumatic disease | 2.6% (20) | 4.7% (18) | 0.050 | 1.895 (0,99-3.626) |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 4.1% (32) | 5.8% (22) | 0.195 | 1,44 (0,825-2.515) |

| Diabetes | 26.8% (209) | 27.4% (104) | 0.807 | 1.033 (0,784-1.361) |

| Renal disease | 46.9% (366) | 78.1% (296) | < 0.001 | 4.055 (3.061-5.371) |

| Liver disease | 18.2% (142) | 42.2% (160) | < 0.001 | 3.283 (2.498-4.314) |

| Cancer/Immunological disease | 41.4% (323) | 45.4% (172) | 0.194 | 1.176 (0,918-1.506) |

| Neurological disease | 10.8% (84) | 9.0% (34) | 0.346 | 0,817 (0.537-1.241) |

Categorical variables displayed as percentage and number; continuous variable displayed as median and interquartile range. *P-value, categorical variables tested with Chi-square test, continuous variable tested with Wilcoxon rank sum test. BSI = blood stream infection, IQR = interquartile range, OR = odds ratio, CI95 = 95% confidence interval. VRE = vancomycin-resistant enterococcus, VSE = vancomycin-susceptible enterococcus. N.a. = not applicable

Bold entries represent statistically significant factors

Table 4.

Results of multivariable binary logistic regression of risk factors for in-hospital death after enterococcal bloodstream infection

| Parameter | VS-E. faecium vs. VS-E. faecalis | VS-E. faecium vs. VR-E. faecium | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | P-value | CI95 (lower-upper) | OR | P-value | CI95 (lower-upper) | ||||||

| Age | 1015 | 0,002 | 1005 | – | 1025 | 1016 | 0,010 | 1004 | – | 1029 | |

| Vascular disease | 1407 | 0,042 | 1012 | – | 1956 | Not significant | |||||

| Renal disease | 3120 | 0,000 | 2274 | – | 4280 | 4005 | 0,000 | 2708 | – | 5922 | |

| Liver disease | 2909 | 0,000 | 2109 | – | 4011 | 2390 | 0,000 | 1618 | – | 3529 | |

| Enterococcus species | VS-E. faecium | 2023 | 0,000 | 1519 | – | 2695 | Not applicable | ||||

| VS-E. faecalis | Reference = 1 | Not applicable | |||||||||

| Vancomycin-resistant | Not applicable | 1.283 | 0.300 | 0.801 | – | 2.057 | |||||

| Vancomycin-susceptible | Not applicable | Reference = 1 | |||||||||

OR = odds ratio, CI95 = 95% confidence interval

Regarding economic aspects, almost all hospital costs were significantly higher in the VREm BSI cohort compared to the VSEm BSI and the VSEf cohort.

Discussion

During the last 15 years (since 2003), 4 meta-analyses on mortality- and financial burden of VRE infections [19, 22–24], and few recent studies on costs associated with VRE infections (not included in the meta-analyses) were published [13, 15, 32]. The studies demonstrate that vancomycin resistance is associated with overall worsened outcome (mortality, length of stay and hospital costs). However, although former studies indicated that E. faecium isolates might be more virulent than E. faecalis isolates irrespective of vancomycin resistance [2, 8, 9, 26], many of the above mentioned studies did not adjust for enterococcal subspecies. As Kaye et al. showed in 2004, this could lead to an overestimation of the outcome effects attributable to vancomycin resistance [9]. Some of the authors discussed this issue in their articles, arguing that meta-analyses cannot improve the quality of data published [22, 24].

In our analyses, in-hospital mortality and length of stay after BSI onset were independently associated with underlying diseases, age and E. faecium but not with vancomycin resistance.

Regarding mortality vancomycin resistance was associated with increased in-hospital mortality in the univariate analysis. This result is in agreement with recent studies including three meta-analyses [19, 22, 24]. However, after adjusting for underlying diseases, age, and species (E. faecium vs. E. faecalis), in-hospital mortality was no longer associated with VRE. There are several possible explanations for these differences with other studies.

Systemic enterococci infections mainly occur in patients with severe underlying diseases and comorbidities [33, 34] which also applies to our study cohort. Patients had a very high Charlson comorbidity score with a median of 7. In this regard, there was no significant difference between the cases infected with E. faecalis, E. faecium or vancomycin-resistant strains. Furthermore, infections caused by antimicrobial-resistant bacteria are often associated with increased morbidity and mortality [19]. These differences are explained by the delay in or even complete lack of an effective antibiotic treatment despite the availability of effective drugs [1, 24]. Prematunge et al. adjusted for appropriate antimicrobial therapy but found that the differences remained [24]. Outcome differences resulting from varying pathogenicity of enterococci species is an alternative explanation [35, 36]. In the multivariable analysis we found only small differences for in-hospital mortality resulting from vancomycin resistance, differences which are insufficient to explain the univariate results. However, we observed significantly increased mortality associated with vancomycin-susceptible E. faecium compared to vancomycin-susceptible E. faecalis.

Possibly because E. faecium is the most common type of VRE worldwide and most E. faecalis isolates from infections are vancomycin-susceptible, it might be a limitation to most existing studies that this confounder is not considered [10–16, 18–24, 32]. Prematunge et al. already pointed out in their 2016 meta-analysis, that it is possible that many observations on VRE-associated outcome are based on differences in the infection-causing species rather than on vancomycin resistance [24].

Attempts to assess the pathogenicity of enterococci go far back in time. In some of the previous studies, the pathogenic potential of commensal E. faecium was determined, whereas most of nowadays HAIs are caused by isolates of a different E. faecium lineage [37, 38]. These so-called hospital-associated strain types (formerly known as clonal complex CC17) differ from commensal human and animal isolates by a distinct core and accessory genome content. Ampicillin resistance is a phenotypic marker of these hospital-associated strain types [39–41]. It has been shown that AMP-R E. faecium isolates causing healthcare-associated infections are in fact more pathogenic than commensal variants [42, 43]. In a supplementary analysis (Additional file 1: Tables S1 and S2) we found that 95% of our E. faecium isolates were ampicillin-resistant (AMP-R), in contrast to only 1% of the E. faecalis isolates. Due to the uneven distribution of ampicillin resistance over the two pathogens we were not able to assess potential virulence differences between commensal and hospital-associated isolates. However, our results are supportive to previous population-based and molecular analyses of E. faecium from hospital-acquired infections.

Several reports have linked VRE infections with increased costs [13, 15, 19, 32]. In the univariate analyses, our data showed similar results as almost all costs were significantly higher in VREm-BSI patients than in patients with VSEm-BSI. Butler et al. reported that pharmacy costs are the second most relevant driver of increased costs, making up to 18% of the total amount [21]. In our cohort, the percentage of pharmaceutical costs for patients with VREm made up 21% of the total hospital costs while they made up only 9% of the costs of patents with BSI caused by VSEm (< 0,001). As we were not able to attribute costs to particular agents, these differences could be due to higher antibiotics costs or to differences in underlying conditions treated. For this reason, we analyzed the length of stay before and after onset of BSI. Our data showed increased lengths of stay overall and before onset of VREm-BSI, but not after. Interestingly, all BSIs were classified as HAIs as none occurred prior to day 3 after hospital admission. On average, the BSI episodes occurred on day 16 of hospitalization. Moreover, the same phenomenon was observed in the analysis of the infection-attributable LOS stratified by the two clinically relevant Enterococcus species. Cases with vancomycin susceptible E. faecium BSI were in-hospital longer before onset of infection than vancomycin susceptible E. faecalis cases. No difference in LOS was observed after onset of infection.

This study has several limitations. The cases were identified retrospectively through a microbiological database and 6.6% lacked sufficient data for this analysis. We did not have data on the course or severity of infection and the antibiotic treatment performed. We did not have separate data on true costs before and after the bloodstream infection. We did not perform molecular analyses on the enterococci isolates to assess their potential virulence traits.

Conclusion

In our study, vancomycin resistance in patients with Enterococcus faecium bloodstream infection was associated with increased total costs, length of stay before onset of infection, but not with infection-attributable LOS or in-hospital mortality. We observed that vancomycin-susceptible E. faecium infections were more strongly associated with increased LOS and mortality than vancomycin susceptible E. faecalis infections and might indicate higher virulence of E. faecium as compared to E. faecalis. In order to avoid overestimation of VRE-attributable effects, in addition to vancomycin-resistance species should be taken into consideration in future studies assessing the burden of VRE infections.

Additional file

Table S1. Susceptibility towards Ampicillin among cases. Table S2. Susceptibility towards Ampicillin among Isolate n=193 missing; AMP= Susceptibility to Ampicillin. R=Resistant. S=Susceptible. RR= relative risk. CI95=95% confidence interval. (DOCX 34 kb)

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Open Access Publication Fund of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

Funding

No external funding was received for this study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 95% CI

95% confidence interval

- BSI

blood stream infection

- CCI

Charlson comorbidity index

- HAI

hospital acquired infection

- HR

Hazard ratios

- IQR

interquartile range

- LOS

length of stay

- ME

multiplicative effect

- VRE

vancomycin-resistant enterococcus

- VREm

vancomycin resistant Enterococcus faecium

- VSE

vancomycin-susceptible enterococcus

- VSEf

vancomycin susceptible E. faecalis

- VSEm

vancomycin susceptible Enterococcus faecium

Authors’ contributions

TSK, CR, PG and RL were responsible for the study design. RL supervised the study. MB, SW and RL were responsible for data collection and data cleaning. FS and RL conducted the statistical analysis. GW helped writing the manuscript and contributed significantly to the discussion. All authors interpreted the data, gave important intellectual content and revised the manuscript critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

A confirmatory ethics vote was obtained from the Charité University Medicine ethics committee (internal processing key EA4/229/17).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Tobias Siegfried Kramer, Email: tobias.kramer@charite.de.

Cornelius Remschmidt, Email: cornelius.remschmidt@charite.de.

Sven Werner, Email: sven.werner@charite.de.

Michael Behnke, Email: michael.bahnke@charite.de.

Frank Schwab, Email: frank.schwab@charite.de.

Guido Werner, Email: wernerg@rki.de.

Petra Gastmeier, Email: petra.gastmeier@charite.de.

Rasmus Leistner, Email: rasmus.leistner@charite.de.

References

- 1.Zasowski EJ, Claeys KC, Lagnf AM, Davis SL, Rybak MJ. Time is of the essence: the impact of delayed antibiotic therapy on patient outcomes in hospital-onset Enterococcal bloodstream infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:1242–1250. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maragakis LL, Perencevich EN, Cosgrove SE. Clinical and economic burden of antimicrobial resistance. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2008;6:751–763. doi: 10.1586/14787210.6.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonten MJ, Willems R, Weinstein RA. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci: why are they here, and where do they come from? Lancet Infect Dis. 2001;1:314–325. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO publishes list of bacteria for which new antibiotics are urgently needed [http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2017/bacteria-antibiotics-needed/en/]. Accessed 5 Mar 2018.

- 5.Gastmeier P, Schroder C, Behnke M, Meyer E, Geffers C. Dramatic increase in vancomycin-resistant enterococci in Germany. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:1660–1664. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon A, Christiansen B. Adaptation and development of German recommendations on the prevention and control of nosocomial infections due to multiresistant pathogens. Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2012;55:1427–1431. doi: 10.1007/s00103-012-1550-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muto CA, Jernigan JA, Ostrowsky BE, Richet HM, Jarvis WR, Boyce JM, Farr BM. SHEA guideline for preventing nosocomial transmission of multidrug-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus and enterococcus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24:362–386. doi: 10.1017/S0195941700083375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cosgrove SE. The relationship between antimicrobial resistance and patient outcomes: mortality, length of hospital stay, and health care costs. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(Suppl 2):S82–S89. doi: 10.1086/499406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaye KS, Engemann JJ, Mozaffari E, Carmeli Y. Reference group choice and antibiotic resistance outcomes. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1125–1128. doi: 10.3201/eid1006.020665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lloyd-Smith P, Younger J, Lloyd-Smith E, Green H, Leung V, Romney MG. Economic analysis of vancomycin-resistant enterococci at a Canadian hospital: assessing attributable cost and length of stay. J Hosp Infect. 2013;85:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayakawa K, Martin ET, Gudur UM, Marchaim D, Dalle D, Alshabani K, Muppavarapu KS, Jaydev F, Bathina P, Sundaragiri PR, et al. Impact of different antimicrobial therapies on clinical and fiscal outcomes of patients with bacteremia due to vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3968–3975. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02943-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheah AL, Spelman T, Liew D, Peel T, Howden BP, Spelman D, Grayson ML, Nation RL, Kong DC. Enterococcal bacteraemia: factors influencing mortality, length of stay and costs of hospitalization. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:E181–E189. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lloyd-Smith P. Controlling for endogeneity in attributable costs of vancomycin-resistant enterococci from a Canadian hospital. Am J Infect Control. 2017;45:e161–e164. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pelz RK, Lipsett PA, Swoboda SM, Diener-West M, Powe NR, Brower RG, Perl TM, Hammond JM, Hendrix CW. Vancomycin-sensitive and vancomycin-resistant enterococcal infections in the ICU: attributable costs and outcomes. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:692–697. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Puchter L, Chaberny IF, Schwab F, Vonberg R-P, Bange F-C, Ebadi E. Economic burden of nosocomial infections caused by vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7:1. doi: 10.1186/s13756-017-0291-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gandra S, Barter D, Laxminarayan R. Economic burden of antibiotic resistance: how much do we really know? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:973–979. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bach PB, Malak SF, Jurcic J, Gelfand SE, Eagan J, Little C, Sepkowitz KA. Impact of infection by vancomycin-resistant enterococcus on survival and resource utilization for patients with leukemia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2002;23:471–474. doi: 10.1086/502089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Russell DL, Flood A, Zaroda TE, Acosta C, Riley MM, Busuttil RW, Pegues DA. Outcomes of colonization with MRSA and VRE among liver transplant candidates and recipients. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transplant Surg. 2008;8:1737–1743. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiang HY, Perencevich EN, Nair R, Nelson RE, Samore M, Khader K, Chorazy ML, Herwaldt LA, Blevins A, Ward MA, Schweizer ML. Incidence and outcomes associated with infections caused by vancomycin-resistant enterococci in the United States: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38:203–215. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNeil SA, Malani PN, Chenoweth CE, Fontana RJ, Magee JC, Punch JD, Mackin ML, Kauffman CA. Vancomycin-resistant enterococcal colonization and infection in liver transplant candidates and recipients: a prospective surveillance study. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:195–203. doi: 10.1086/498903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butler AM, Olsen MA, Merz LR, Guth RM, Woeltje KF, Camins BC, Fraser VJ. Attributable costs of enterococcal bloodstream infections in a nonsurgical hospital cohort. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:28–35. doi: 10.1086/649020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DiazGranados CA, Zimmer SM, Klein M, Jernigan JA. Comparison of mortality associated with vancomycin-resistant and vancomycin-susceptible enterococcal bloodstream infections: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:327–333. doi: 10.1086/430909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salgado CD, Farr BM. Outcomes associated with vancomycin-resistant enterococci: a meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24:690–698. doi: 10.1086/502271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prematunge C, MacDougall C, Johnstone J, Adomako K, Lam F, Robertson J, Garber G. VRE and VSE bacteremia outcomes in the era of effective VRE therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:26–35. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray BE. Vancomycin-resistant enterococcal infections. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:710–721. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003093421007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noskin GA, Peterson LR, Warren JR. Enterococcus faecium and enterococcus faecalis bacteremia: acquisition and outcome. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:296–301. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jahresbericht. 2015. [https://www.charite.de/fileadmin/user_upload/portal_relaunch/Mediathek/publikationen/jahresberichte/Charite_Jahresbericht_2015_EN.pdf]. Accessed 27 Mar 2018.

- 28.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thygesen SK, Christiansen CF, Christensen S, Lash TL, Sorensen HT. The predictive value of ICD-10 diagnostic coding used to assess Charlson comorbidity index conditions in the population-based Danish National Registry of patients. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:83. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schulgen G, Kropec A, Kappstein I, Daschner F, Schumacher M. Estimation of extra hospital stay attributable to nosocomial infections: heterogeneity and timing of events. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:409–417. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnett AG, Beyersmann J, Allignol A, Rosenthal VD, Graves N, Wolkewitz M. The time-dependent bias and its effect on extra length of stay due to nosocomial infection. Value Health. 2011;14:381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang HL, Zhou Z, Wang LS, Fang Y, Li YH, Chu CI. The risk factors, costs, and survival analysis of invasive VRE infections at a medical Center in Eastern Taiwan. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;54:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guzman Prieto AM, van Schaik W, Rogers MR, Coque TM, Baquero F, Corander J, Willems RJ. Global emergence and dissemination of enterococci as nosocomial pathogens: attack of the clones? Front Microbiol. 2016;7:788. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.von Baum H, Ober JF, Wendt C, Wenzel RP, Edmond MB. Antibiotic-resistant bloodstream infections in hospitalized patients: specific risk factors in a high-risk population? Infection. 2005;33:320–326. doi: 10.1007/s15010-005-5066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arias CA, Murray BE. The rise of the enterococcus: beyond vancomycin resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:266–278. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sava IG, Heikens E, Huebner J. Pathogenesis and immunity in enterococcal infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:533–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao W, Howden BP, Stinear TP. Evolution of virulence in enterococcus faecium, a hospital-adapted opportunistic pathogen. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2018;41:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2017.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lebreton F, van Schaik W, McGuire AM, Godfrey P, Griggs A, Mazumdar V, Corander J, Cheng L, Saif S, Young S. Emergence of epidemic multidrug-resistant enterococcus faecium from animal and commensal strains. MBio. 2013;4:e00534–e00513. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00534-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lester CH, Sandvang D, Olsen SS, Schønheyder HC, Jarløv JO, Bangsborg J, Hansen DS, Jensen TG, Frimodt-Møller N, Hammerum AM. Emergence of ampicillin-resistant enterococcus faecium in Danish hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:1203–1206. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Top J, Willems R, Blok H, De Regt M, Jalink K, Troelstra A, Goorhuis B, Bonten M. Ecological replacement of enterococcus faecalis by multiresistant clonal complex 17 enterococcus faecium. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13:316–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Freitas AR, Novais C, Duarte B, Pereira AP, Coque TM, Peixe L. High rates of colonisation by ampicillin-resistant enterococci in residents of long-term care facilities in Porto, Portugal. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018;51:503–507. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zou J, Shankar N. Surface protein Esp enhances pro-inflammatory cytokine expression through NF-κB activation during enterococcal infection. Innate immunity. 2016;22:31–39. doi: 10.1177/1753425915611237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sillanpää J, Nallapareddy SR, Singh KV, Prakash VP, Fothergill T, Ton-that H, Murray BE. Characterization of the ebpfm pilus-encoding operon of enterococcus faecium and its role in biofilm formation and virulence in a murine model of urinary tract infection. Virulence. 2010;1:236–246. doi: 10.4161/viru.1.4.11966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Susceptibility towards Ampicillin among cases. Table S2. Susceptibility towards Ampicillin among Isolate n=193 missing; AMP= Susceptibility to Ampicillin. R=Resistant. S=Susceptible. RR= relative risk. CI95=95% confidence interval. (DOCX 34 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.