Abstract

Background

Vascular dementia is the second most common type of dementia that causes cognitive dysfunction. Acupuncture, an ancient therapy, has been mentioned for the treatment of vascular dementia in previous studies. This study aimed to evaluate the effects of acupuncture in animal models of vascular dementia.

Methods

Experimental animal studies of treating vascular dementia with acupuncture were gathered from Embase, PubMed and Ovid Medline (R) from the dates of the databases’ creation to December 2016. We adopted the CAMARADES 10-item checklist to evaluate the quality of the included studies. The Morris water maze test was considered as an outcome measure. The software Stata12.0 was used for the meta-analysis. Heterogeneity was examined using I2 statistics, and we conducted subgroup analyses to determine the causes of heterogeneity for escape latency and duration in original platform.

Results

Sixteen studies involving 363 animals met the inclusion criteria. The included studies scored between 4 and 8 points, and the mean was 5.44. The results of the meta-analysis indicated remarkable differences with acupuncture on increasing the duration in the former platform quadrant both in EO models (SMD = 1.56, 95% CI: 1.02 ~ 2.11; p < 0.00001) and 2-VO models (SMD 4.29, 95% CI 3.23 ~ 5.35; p < 0.00001) compared with the control groups.

Conclusions

Acupuncture may be effective in improving cognitive function in vascular dementia animal models. The mechanisms of acupuncture for vascular dementia are multiple such as anti-apoptosis, antioxidative stress reaction, and metabolism enhancing of glucose and oxygen.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12906-018-2345-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Acupuncture, Vascular dementia, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Background

Vascular dementia (VD) is a heterogeneous group of brain disorders of which the cognitive impairment can be ascribed to cerebrovascular pathologies; more than 20% cases of dementia are vascular dementia, making it the second most prevalent form of dementia, second only to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1]. Advanced age, diabetes, hypertension, smoking and atrial fibrillation are all risk factors for vascular dementia [2]. Level of education, which is considered to be an effective alternative indicator of cognitive reserves, has a significant association with the expression of VD in that higher education appears to be associated with fewer cognitive deficits [3, 4]. As the populations of North America and European countries age, the risk of VD in these regions approximately doubles every 5.3 years. However, the current study suggests that effective therapy for vascular dementia has proven to be more difficult than for Alzheimer’s disease. While memantine and cholinesterase inhibitor drugs have been proven to be significantly effective in treating Alzheimer’s disease and are therefore labeled for this indication, they are not recommended for use in the treatment of vascular dementia by either regulatory bodies or guideline groups due to their overall low effectiveness and possible side effects [5–7].

Acupuncture, an economical type of traditional Chinese therapy with minimal side effects, has been used for many diseases in Asian countries for thousands of years and is widely used for rehabilitation after stroke [8]. Usually after a stroke, 15–30% of subjects will develop vascular dementia within three months, and delayed dementia will develop in the long term due to recurrent stroke in 20–25% of subjects [9]. In recent years, more and more studies, and especially animal experiment studies, have been published to illustrate the effectiveness of acupuncture for vascular dementia.

Until now, no systematic meta-analysis has been published to analyze the effects of acupuncture on enhancing cognitive function in vascular dementia animal models. A systematic review of animal experiments can be beneficial for future experimental designs and provide a basis for clinical studies. Additionally, it can provide valuable directions for further research. It is for these reasons that we conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis complied with standard guidelines (See Additional file 1).

Search strategy

The following electronic databases were searched from database inception to December 2016: Embase, PubMed and Ovid Medline (R), and the following keywords were used: acupuncture, electroacupuncture, acupoint, vascular dementia, multi-infarct dementia and multiinfarct dementia. The search language was limited to English, and we also tried to collect records from other sources. The detailed search strategies are shown in Additional file 2.

Inclusion criteria

Subjects: Animal models of vascular dementia were included.

Intervention: Only manual acupuncture and electroacupuncture (EA) were included.

Outcome: The Morris water maze test was used to evaluate cognitive functions in animal models.

Language: Only articles published in English were included.

No publication date limit was set, and the search was conducted in December 2016.

Exclusion criteria

Duplicate articles;

Studies that have no control group;

Auricular acupuncture, laser acupuncture and other acupuncture techniques;

Acupuncture therapy combined with the use of traditional Chinese medicines or Western drugs;

Studies aiming to compare different acupuncture techniques;

Studies that only compared acupuncture with traditional Chinese medicines.

Study selection and data extraction

One reviewer (ZYZ) generated the search strategy, searched the databases, and made a list of all the records. Two evaluators (HHD, QC) independently evaluated the articles based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements were solved together through discussions (ZYZ, HHD, QC). Two reviewers (HHD, QC) independently extracted the data.

The following data were extracted: publication year, the last name of the first author, model of vascular dementia, weight range of the included animals, number of animals included, method of treatment with timing and duration in the acupuncture and control groups, the assessment of trials, and the results of each article (positive or negative). The final outcomes were extracted if several outcomes were presented. When the outcome data were only shown graphically, we attempted to contact the authors to obtain the detailed data; if we received no response to our request, we used GetData software to measure the data. Differences were solved together through discussions (HHD, QC, ZYZ).

Risk of bias assessment

We evaluated methodological quality against an ten-item checklist [10]: (1) peer-reviewed journal; (2) temperature control; (3) animals were randomly allocated; (4) blind established model; (5) blinded outcome assessment; (6) anesthetics used without marked intrinsic neuroprotective properties; (7) animal model (diabetic, advanced age or hypertensive); (8) calculation of sample size; (9) statement of compliance with animal welfare regulations; (10) possible conflicts of interest.

The quality of each study was evaluated by a score from zero to ten. Two evaluators (HHD, QC) independently extracted the data and assessed the quality of each study. Disagreements were resolved through discussion (HHD, QC, ZYZ).

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, we used the statistical software package Stata version 12.0. The data of the Morris water maze test, such as escape latency, time in the quadrant in which the former platform was located, and frequency of crossing through the former platform were considered continuous data, and we therefore calculated standard mean differences (SMD) with confidence intervals (CIs) established at 95%. Heterogeneity in the studies was examined using I2 statistics. If the I2 statistic was higher than 50%, we considered significant heterogeneity to be present, and we used a random effects model. Otherwise, we used a fixed effect model. When significant heterogeneity existed, the subgroup analysis would be conducted based on animal species, acupuncture methods and modeling methods. We used Egger’s test and Begg’s test to assess publication bias.

Results

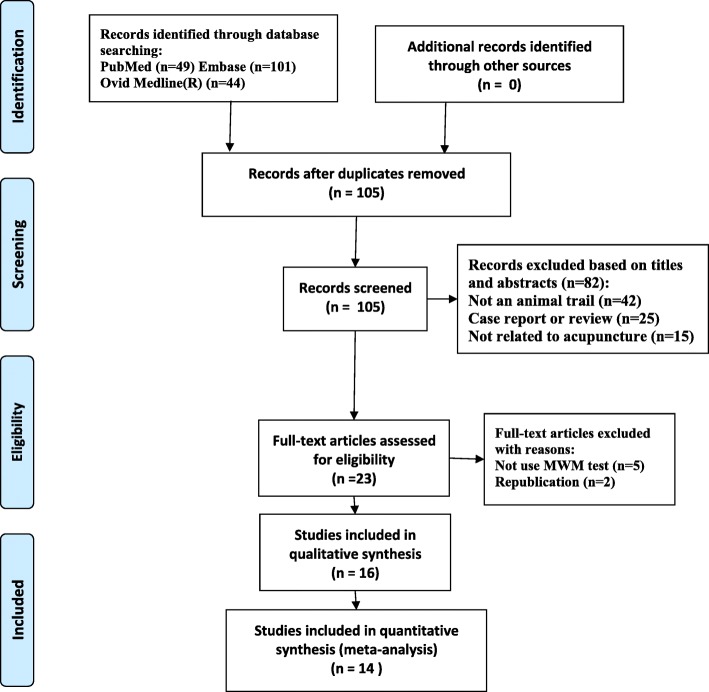

We identified 194 possibly relevant studies in the initial search. After duplicates had been removed, we screened the titles and the abstracts of 105 remaining records, and 82 records were excluded. For further screening, 23 remaining articles were downloaded. Eventually, 16 studies met the inclusion criteria [11–26]. The selection process flow diagram is shown in Fig. 1 [27].

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process. MWM:Morris water maze

Study characteristics

The 16 studies included involved 363 rats, 174 of which were in an acupuncture group and 189 of which were in a control group. All the studies stated the weight range of the rats, which ranged from 180 to 490 g. A total of 7 of the 16 studies mentioned the age of the animals [11, 14, 16–18, 23, 25], which ranged from 2 months old to 12 months old. Sixteen of the included studies used different subtests of the Morris water maze test; all the studies met the inclusion criteria by using escape latency as outcome data, while two studies used swimming speed [24, 26], five studies used duration in the quadrant of the former platform position [12, 13, 21, 24, 26], one used swimming distance [19], and three used frequency of crossing former platform [12, 15, 16]. Two species of rats were used in the 16 studies: seven studies used Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats [11, 13, 15, 17–19, 25], and nine studies used Wistar rats [12, 14, 16, 20–24, 26]. The basic characteristics of the studies are listed in Table 1 [28].

Table 1.

Data of 16 included studies

| Trial | Species(Na/Nc) | Age(month) | Weigh(g) | Model | Acupuncture(acupoints) | Control intervention | Outcome assessment | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang 2004 [11] | SD rats (14/13) SD rats (14/13) |

2~ 3 | 200–250 | 4-VO | EA,20 min/d for 15d, 150HZ, 2 mA, continuous Waveform (GV14, GV20) |

No treatment Nimodipine |

Escape latency Escape latency |

P < 0.01 P > 0.05 |

| Yu 2005 [12] | Wistar rats (15/14) |

NR | 340 ± 40 | EO | manual acupuncture, 30 s/d for 21 d (CV6, CV12, CV17, SP10, ST36) |

Placebo-acupuncture | Escape latency Duration in former platform position Frequency crossing former platform |

P < 0.05 P < 0.05 P < 0.05 |

| Shao 2008 [13] | SD rats (9/8) SD rats (9/8) |

NR | 180–220 | 4-VO | EA,20 min/d for 15 d, 150 HZ, 1–2 mA, Continuous Waveform (BL17, BL20, BL23, GV20) |

No treatment Nimodipine |

Escape latency Escape latency |

P < 0.01 P > 0.05 |

| Wang 2009 [14] | Wistar rats(11/11) | 10 | 300 ± 40 | EO | manual acupuncture, 30 s/d for 21 d (CV6, CV12, CV17, SP10, ST36) | Placebo-acupuncture | Escape latency Duration in former platform position |

P < 0.05 P < 0.01 |

| Wei 2011 [15] | SD rats(10/10) | NR | 200–250 | 2-VO | EA, 20 min/d for 10 d, 50 HZ,1.0 mA, continuous Waveform (GV14, GV20) | No treatment Nimodipine |

Escape latency Frequency crossing former platform Escape latency Frequency crossing former platform |

P < 0.01 P < 0.01 P > 0.01 P > 0.01 |

| Zhao 2011 [16] | Wistar rats(10/10) | 4 | 240 ± 20 | EO | manual acupuncture, 30 s/d for 21 d(CV6, CV12, CV17, SP10, ST36) | Placebo-acupuncture | Escape latency Swimming Speed |

P < 0.01 P > 0.05 |

| Zhu 2011 [17] | SD rats(11/12) | 9 | 460 ± 30 | 2-VO | EA, 20 min/d for 30 d,4HZ, 2.0 mA, continuous waveform (BL23, GV14, GV20) | No treatment | Escape latency | P < 0.01 |

| Zhu 2012 [18] | SD rats(12/10) | 12 | 400 ± 30 | 2-VO | EA, 20 min/d for 30 d,4 HZ, 2.0 mA, continuous waveform (BL23, GV14, GV20) | No treatment | Escape latency | P < 0.05 |

| Zhu 2013 [19] | SD rats(6/6) | NR | 432 ± 30 | 2-VO | EA, 20 min/d for 30 d, 4HZ, continuous waveform (BL23, GV14, GV20) | No treatment | Escape latency | P < 0.05 |

| Yang 2014 CG [20] | Wistar rats (12/12) | NR | 200–250 | 2-VO | manual acupuncture, 360 min/d for 21 d (Frontal region, frontoparietal region and parietal region) | No treatment | Escape latency Swimming distance |

P < 0.05 P < 0.05 |

| Yang 2014 CG [20] | Wistar rats (12/12) | NR | 200–250 | 2-VO | manual acupuncture, 360 min/d for 21 d (Frontal region, frontoparietal region and parietal region) | No treatment | Escape latency Swimming distance |

P < 0.05 P < 0.05 |

| Zhang 2014 [21] | Wistar rats (10/10) | NR | 300–320 | EO | manual acupuncture, 30 s/d for 21 d (CV6, CV12, CV17, SP10, ST36) | Placebo-acupuncture | Escape latency Frequency crossing former platform Duration in former platform position |

P < 0.01 P < 0.01 P < 0.01 |

| Li 2015 [22] | Wistar rats (11/11) | NR | 320–360 | EO | manual acupuncture,30 s/d for 14 d (ST36) | Placebo-acupuncture | Escape latency | P < 0.05 |

| Li 2015 [23] | Wistar rats (10/10) | 2 | 300–320 | EO | manual acupuncture, 30 s/d for 14 d (ST36 | Placebo-acupuncture | Escape latency | P < 0.05 |

| Wang 2015 [24] | Wister rats(10/10) | NR | 200–220 | 2-VO | manual acupuncture, 30 s/d for 21 d (CV6, CV12, CV17, SP10, ST36) | Placebo-acupuncture | Escape latency Swimming speed Duration in former platform position |

P < 0.05 P > 0.05 P < 0.05 |

| Fang 2016 [25] | SD rats(18/18) | 9 | 300–450 | MCAO | EA, 20 min/d for 30 d, 30HZ, 6-15 V, sparse wave (BL23, GV14, GV20) | No treatment | Escape latency | P < 0.05 |

| Li 2016 [26] | Wister rats (14/14) | NR | 270–320 | 2-VO | manual acupuncture, 30 s/d for 14 d (ST36) | Placebo-acupuncture | Escape latency Duration in former platform position Swimming speed |

P < 0.01 P < 0.01 P > 0.05 |

Na number of animals in the acupuncture group, EA electroacupuncture, Nc number of animals in the control group, SD Sprague Dawley, 4-VO 4-vessel occlusion, EO embolic occlusion, 2-VO bilateral common carotid artery occlusion, NR no record, PG positive control group, CG cluster-needling group, MCAO middle cerebral artery occlusion

Model preparation method

Various methods were used to establish a vascular dementia (VD) model in the different studies (Table 1) [29]. The 4-vessel occlusion (4-VO) method was used in two studies [11, 13]; 7 studies used bilateral common carotid artery occlusion (2-VO) [15, 17–20, 24, 26]; 6 studies used embolic occlusion (EO) [12, 14, 16, 21–24]; and the remaining trial used middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) [25].

Description of acupuncture

A range of acupuncture techniques was employed with regard to the combinations of acupoints, the stimulation method (EA or manual acupuncture) and manipulation. Five studies used acupoints CV6 (Zhongji), CV12 (Zhongwan), CV17 (Danzhong), SP10 (Xiehai), ST36 (Zusanli) [12, 14, 16, 21, 24], which was the most commonly used technique. Three studies chose to apply acupuncture treatment to a single acupoint, ST36 (Zusanli) [22, 23, 26]. Four studies used BL23 (Shenshu), GV14 (Dazhui), and GV20 (Baihui) [17–19, 25]. Two studies used GV14 (Dazhui) and GV20 (Baihui) [11, 15]. One study used BL17 (Geshu), BL20 (Pishu), BL23 (Shenshu), and GV20 (Baihui) [13]. The final study had two acupuncture groups [20]: the group called the positive control group used GV14 (Dazhui) and GV20 (Baihui), and the other group, the cluster-needling group, used the frontal region, the frontoparietal region, and the parietal region. Nine studies chose manual acupuncture as the method of stimulation [12, 14, 16, 20–24, 26], while the other seven studies used electroacupuncture [11, 13, 17–19, 25]. Almost all of the studies that used manual acupuncture adopted 30s as their treatment duration; the exception was the study that had two acupuncture groups [20], the positive control group and the cluster-needling group, which used 60 min and 360 min. Of the 7 EA studies, six of the studies adopted continuous waves [11, 13, 15, 17–19], of which the frequency ranged from 4 Hz to 150 Hz, and the current density was from 1 to 2 mA. The remaining study adopted sparse wave [25], of which the frequency was 30 Hz. A summary of the acupuncture treatment protocols is shown in Table 1.

Control interventions

Ten studies adopted some interventions in the control groups. The Western medicine nimodipine was used as a control intervention in three studies [11, 13, 15], and the remaining seven studies adopted placebo-acupuncture as a control intervention [12, 14, 16, 22–24, 26].

Study quality assessment

The study quality scores ranged from 4 to 8. Four studies scored points in 4 items [13, 16, 21, 23]; four studies scored points in 5 items [11, 12, 14, 17]; six studies scored points in 6 items [15, 18, 19, 24–26]; one study scored 7 points [22]; and the remaining study scored 8 points [20]. All of the included studies were published in peer-reviewed journals. Eleven of the studies mentioned control of temperature [11–13, 15, 18–20, 22, 24–26], which included room temperature or the temperature of the water in the maze. All of the studies adopted random allocation. Blinded building of the model was adopted in 13 studies [11, 12, 14–17, 19–22, 24–26]. Blinded outcome assessment was adopted in 2 studies [22, 23]. Twelve studies stated the use of anesthetics without marked intrinsic neuroprotective properties [11, 12, 14, 15, 17–20, 22–24, 26]. No study adopted a diabetic, hypertensive or aged animal model, and no study reported sample size calculations. Eight studies mentioned compliance with animal welfare regulations [14, 15, 18, 20, 21, 23–26]. Seven studies stated possible conflicts of interest [13, 16–18, 20, 22, 25]. The study quality assessment is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Methodological quality assessment of the included studies

| Study | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang 2004 [11] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | 5 |

| Yu 2005 [12] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | 5 |

| Shao 2008 [13] | Y | Y | Y | N | N | U | N | N | N | Y | 4 |

| Wang 2009 [14] | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | 5 |

| Wei 2011 [15] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | 6 |

| Zhao 2011 [16] | Y | N | Y | Y | N | U | N | N | N | Y | 4 |

| Zhu 2011 [17] | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | 5 |

| Zhu 2012 [18] | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6 |

| Zhu 2013 [19] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | 6 |

| Yang 2014 [20] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 8 |

| Zhang 2014 [21] | Y | N | Y | Y | N | U | N | N | Y | N | 4 |

| Li 2015 [22] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | 7 |

| Li 2015 [23] | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | 4 |

| Wang 2015 [24] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | 6 |

| Fang 2016 [25] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | N | N | Y | Y | 6 |

| Li 2016 [26] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | 6 |

(1) Peer-reviewed journal. (2) Temperature control. (3) Animals were randomly allocated. (4) Blind established model. (5) Blinded outcome assessment. (6) Anesthetics used without marked intrinsic neuroprotective properties. (7) Animal model (diabetic, advanced age or hypertensive). (8) Calculation of sample size. (9) Statement of compliance with animal welfare regulations. (10) Possible conflicts of interest

Y, Yes(low risk bias); N, No(high risk bias); U, Unclear

Morris water maze outcomes analyses

Escape latency

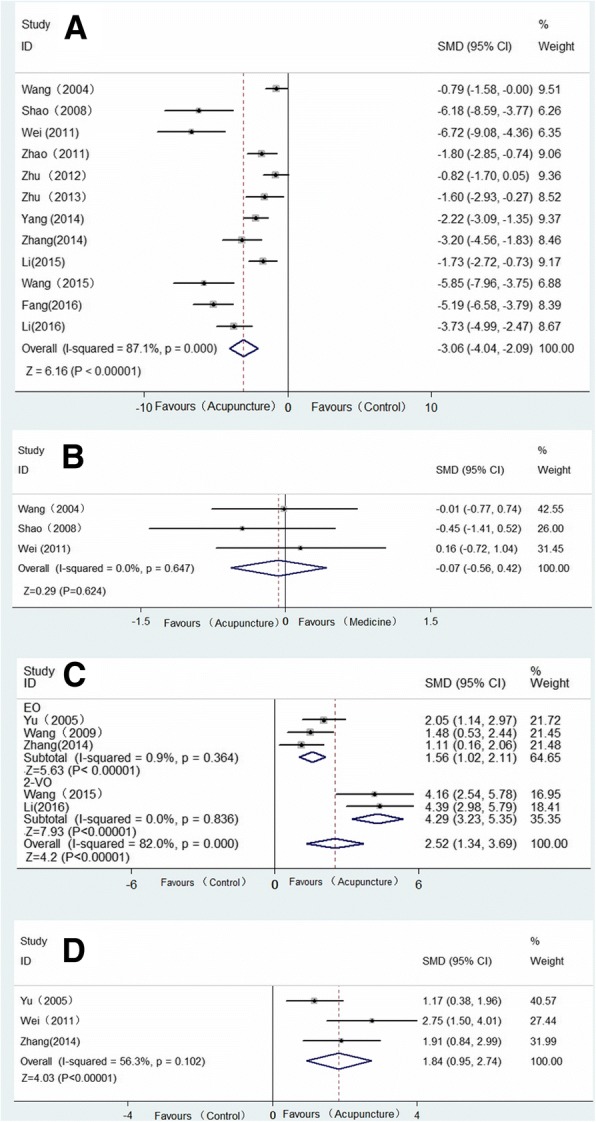

Twelve studies adopted escape latency as an outcome index. And all of these studies reported the positive effectiveness of acupuncture on reducing escape latency, except for the one study [20] that was designed with two acupuncture groups, the positive control group and cluster-needling group, which showed negative results and positive results, respectively. Of these 12 studies, six of them provided detailed data regarding the marked effect of acupuncture [11, 13, 15, 18–20], and we extracted the data from the other six studies that demonstrated the data in a graphical representation by using GetData software [16, 21–26]. To avoid double-counting [30], the effects of different acupuncture intervention arms included in a single study were averaged and entered once in the analysis [20] [n = 280, SMD = − 3.06, 95%CI (− 4.04~ − 2.09), p < 0.00001; heterogeneity I2 = 87.1%, random effects model, Fig. 2a] [31–33]. Three studies compared the effect of acupuncture with nimodipine [11, 13, 15], and all three of these studies concluded that escape latency was not significantly different between the medication group and the acupuncture group [n = 64, SMD = − 0.07, 95% CI (− 0.56 ~ 0.42), p = 0.775 > 0.05; heterogeneity I2 = 0%, fixed effect model, Fig. 2b].

Fig. 2.

Forest plot showed that escape latency decreases with acupuncture therapies in vascular models. Effect of acupuncture on outcomes of the water maze: effect on (a) escape latency time versus the control group; (b) escape latency time versus nimodipine; (c) duration in original platform; (d) frequency of crossing former platform

Duration in original platform

Five studies showed the effect of acupuncture on improving the duration in the quadrant of the former platform compared with the control group (VD group or placebo-acupuncture group) [12, 14, 21, 24, 26]. All five of these studies reported positive results, but none of them provided detailed data [13]; we therefore extracted the data from the figures [n = 119, SMD = 2.52, 95%CI (1.34 ~ 3.69), p < 0.00001; heterogeneity I2 = 82.0%, random effects model, Fig. 2c].

Frequency of crossing former platform

Three studies reported the positive results of acupuncture on increasing the frequency of crossing the former platform location [12, 15, 21] [n = 69, SMD = 1.84, 95% CI (0.95 ~ 2.74), p < 0.00001; heterogeneity I2 = 56.3%, random effects model, Fig. 2d].

There was no significant difference observed in the animals’ swimming speed in the water maze in the two studies that measured it, although the detailed data were unavailable [24, 26].

Subgroup analyses

Escape latency

Animal species

Acupuncture was found to have a remarkable effect on reducing escape latency time in both Sprague-Dawley rats (SMD –3.33, 95% CI –5.18 ~ − 1.47; p < 0.00001) and Wister rats (SMD –2.85, 95% CI –3.79~ − 1.91; p = 0.002). The subgroup analysis observed that Wister rats had slightly reduced heterogeneity (I2 = 73.5%), while Sprague-Dawley rats did not (I2 = 92.1%).

Acupuncture methods

We performed a subgroup analysis of the methods of acupuncture used (Table 3) and observed significant effects of manual acupuncture (SMD –3.11, 95% CI –4.23 ~ − 2.00; p = 0.002) and electro-acupuncture (SMD –3.05, 95% CI –4.56~ − 0.78; p < 0.00001) on reducing escape latency time. Subgroup analysis of the acupuncture methods indicated that manual acupuncture had reduced heterogeneity (I2 = 75.9%), while electroacupuncture did not (I2 = 90.5%).

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis for the effect of acupuncture on reducing escape latency time

| SMD | LL | HL | Degrees of freedom | Heterogeneity | Effect size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 | Z | P | ||||||

| Species | SR | −3.33 | −5.18 | −1.47 | 5 | 92.10% | 3.52 | P < 0.00001 |

| WR | −2.85 | −3.79 | −1.91 | 5 | 73.50% | 5.93 | P = 0.002 | |

| Modeling | 2-VO | −2.97 | −4.21 | − 1.73 | 6 | 85.80% | 4.69 | P < 0.00001 |

| 4-VO | −3.36 | −8.63 | 1.92 | 1 | 94.30% | 1.25 | P = 0.212 | |

| EO | −2.38 | −3.82 | −0.95 | 1 | 65.80% | 3.26 | P = 0.001 | |

| MCAO | −5.19 | −6.58 | −3.79 | 0 | – | 7.29 | P < 0.00001 | |

| Methods | EA | −3.05 | −4.56 | −1.53 | 6 | 90.50% | 3.94 | P < 0.00001 |

| MA | −3.11 | −4.23 | −2.00 | 4 | 75.90% | 5.47 | P = 0.002 | |

| OVERALL | −3.06 | −4.04 | −2.09 | 11 | 87.10% | 6.04 | P < 0.00001 | |

SR Sprague–Dawley Rats, WR Wister Rats, 2-VO bilateral common carotid artery occlusion, VO 4-vessel occlusion, EO embolic occlusion, MCAO middle cerebral artery occlusion, EA Electroacupuncture, MA Manual acupuncture

Modeling methods

We also conducted a subgroup analysis of the modeling methods (Table 3) [31]. This subgroup analysis showed that acupuncture had a significant effect on 2-VO models (SMD –2.97, 95% CI –4.21~ − 1.73; p < 0.00001), EO models (SMD –2.38, 95% CI –3.82~ − 0.95; p = 0.001), and MCAO models (SMD –5.29, 95% CI –6.58~ − 3.79; p < 0.00001), but no remarkable difference was found in the 4-VO models (SMD –3.36, 95% CI –8.63 ~ 1.92; p = 0.212 > 0.05).

Duration in original platform

Modeling methods

For all five of the studies that regarded duration in original platform as an outcome measure, adopted electroacupuncture, and used Wister rats, we only conducted a subgroup analysis of the modeling methods (Fig. 2c). Both the EO models (SMD 1.56, 95% CI 1.02 ~ 2.11; p < 0.00001) and the 2-VO models (SMD 4.92, 95% CI 3.23 ~ 5.35; p < 0.00001) found a remarkable effect with the use of electroacupuncture, and this subgroup analysis significantly reduced the heterogeneity (EO: I2 = 0.9%, 2-VO: I2 = 0%).

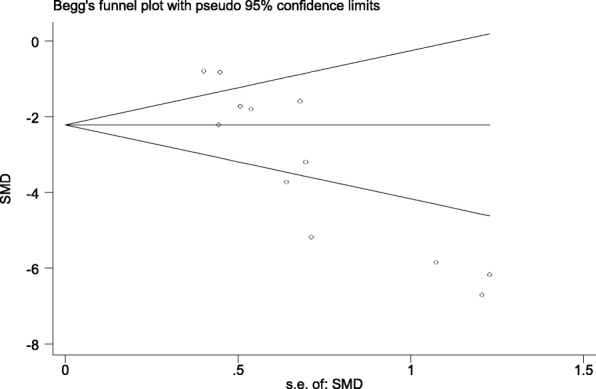

Publication bias test

We performed a publication bias test for the outcome of escape latency using Egger’s test (Pr > |z| = 0.001 < 0.05, continuity corrected) and Begg’s test (Pr > |z| = 0.005 < 0.05, continuity corrected, Fig. 3). The results of these two tests indicated the potential existence of publication bias across all of the included studies [34]. We did not conduct a publication bias test for the other outcome measures, because there were fewer than ten included studies for each measure [35].

Fig. 3.

Begg’s test for the outcome of escape latency

Signaling pathways

Of the sixteen included studies, fifteen described possible mechanisms of acupuncture in ameliorating cognitive function. The main signaling pathways were summarized in three aspects, oxidative stress damage reduction, nerve apoptosis suppression and neurogenesis. See Table 4 [36, 37].

Table 4.

Proposed mechanisms

| Study | Findings & Proposed mechanisms |

|---|---|

| Wang 2004 [11] | • Reduced NO, NOS and MDA • Increased SOD and GSH-Px |

| Shao 2008 [13] | Increased AVP and SS |

| Wang 2009 [14] | • Up-regulating the expression of Bcl-2 • Counter-regulated the pro-apoptotic Bax |

| Wei 2011 [15] | Promoting synaptic function and structure |

| Zhao 2011 [16] | Enhanced hexokinase, pyruvate kinase and glucose 6 phosphate dehydrogenase activities |

| Zhu 2011 [17] | Inhibiting expression of p53 and Noxa |

| Zhu 2012 [18] | Increased p70S6K and ribosomal protein S6 |

| Zhu 2013 [19] | Increased mTOR and eIF4E |

| Yang 2014 [20] | Increased hippocampal ACh, DA, and 5-HT |

| Zhang 2014 [21] | Increased CBF |

| Li 2015 [22] | Increase pyramidal neuron number in hippocampal CA1 area |

| Li 2015 [23] | • Inhibited PDE activity • Activated ERK and cAMP/PKA/CREB |

| Wang 2015 [24] | Enhanced Nrf2 |

| Fang 2016 [25] | Decreased TNF-α mRNA, IL-6 mRNA and IL-1β mRNA |

| Li 2016 [26] | • Increased complex I, II, IV and cox IV • Decreased ROS |

NO nitric oxide, NOS nitric oxide synthase, MDA malondialdehyde, GSH-Px glutathione peroxidase, AVP arginine vasopressin, SS somatostatin, Bcl-2 B-cell lymphoma-2, Bax Bcl-2 associated X protein, P53 Tumor protein P53, P70S6K P70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase, mTOR mammalian target of rapamycin, eIF4E eukaryotic translation initiation factor, Ach acetylcholine, DA dopamine, 5-HT 5-hydroxytryptamine, CBF cerebral blood flow, PDE phosphodiesterase, ERK extracellular signal-regulated kinase, cAMP 3′,5′-cyclic AMP/protein kinaseA, PKA protein kinaseA, CREB cAMP/PKA/cAMP response element binding protein, Nrf2 nuclear factor erythroid-related factor 2, TNF tumor necrosis factor, IL interleukin, coxIV cytochrome oxidase IV, ROS reactive oxygen species

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this report describes the first systematic meta-analysis exploring the effect of acupuncture on vascular dementia in animal experiments with the results of the Morris water maze test as the outcome assessment.

Implications

This study indicates that electroacupuncture could increase the duration in the former platform quadrant both in EO models (SMD = 1.56, 95% CI: 1.02 ~ 2.11; p < 0.00001; heterogeneity: I-squared = 0.9%) and 2-VO models (SMD = 4.29, 95% CI: 3.23 ~ 5.35; p < 0.00001; heterogeneity: I-squared = 0%) compared with the control groups. This finding suggests that acupuncture may play a potential role in ameliorating cognitive dysfunction in animal models. A previous study indicates that the addition of acupuncture therapy to routine care may have beneficial effects on improvements in cognitive status but limited efficacy on health-related quality of life in vascular dementia patients [38].

The high heterogeneity between the studies based on escape latency time cannot be completely explained. We conducted subgroup analyses based on the method of stimulation, the modeling method and the animal species used, but no evident cause was found. Meanwhile, the subgroup analysis of the modeling methods that regarded the duration in former platform as an outcome measure obviously reduced the heterogeneity. We found all five of the studies in this analysis adopted the same method of stimulation, the same animal species, and similar acupoint combinations. Four of the five studies used CV6, CV12, CV17, SP10, and ST36, the other study used ST36. These findings indicate that, in addition to the differences in stimulation method, modeling methods and animal species used, acupoint combinations may be another source of heterogeneity among the studies.

Systematic reviews can help promote the methodological quality of preclinical animal studies. Systematic reviews can help promote the methodological quality of preclinical animal studies. Essential methodological details are significant to measure the quality of a body of evidence and to assess the bias risk in animal trials. However, the insufficiency of the methodology is evident in many aspects of the present study. For instance, an adequate target animal model represents an important aspect to improve the quality of the experimental design. All included studies were performed on healthy and young animals. However, vascular dementia [39] generally occurs in aged, diabetic or hypertensive patients; therefore, experiments using young and healthy animals may overestimate the effectiveness of the intervention [10]. Hence, appropriate target animal models (hypertensive, advanced age and diabetic) should be used in future experimental research.

The included studies investigated several signaling pathways to gain a better understanding of the mechanism of improving cognitive function via acupuncture, including modulating the production and degradation of free radicals to reduce brain damage [11], exerting anti-apoptotic effects by up-regulating B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) and counter-regulating Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax) to protect neurons [14], enhancing glucose metabolism in the brain [16], reducing tumor protein P53 and Noxa expression to protect pyramidal cells from apoptosis [17], increasing cerebral blood flow for increased glucose and oxygen supply to neurons [21], exerting neuroprotective effects via an antioxidative pathway mediated by nuclear factor erythroid2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) [24], and increasing complex enzymes to protect neurons from oxidative stress [26]. The present study indicated that acupuncture protects neurons during vascular dementia mainly through enhancing oxygen and glucose metabolism and anti-apoptosis and antioxidant properties. However, the signaling pathways targeted by acupuncture were infrequently and incompletely reported. Therefore, this field should be further explored in future clinical studies.

Limitations

This systematic meta-analysis has several limitations, the first of which is language bias. We limited the language of our searches to English only, which may cause potential publication bias. The results may have differed if we had included studies reported in Chinese, Korean, Japanese or other languages. Second, the total sample size was still not big enough, although we made a concerted effort to search all of the studies that met the inclusion criteria. Third, the quality of the included studies was unsatisfactory, which had an important influence on the results of the systematic meta-analysis. Fourth, evident availability bias was caused by two included studies from which the data cannot be extracted [35]. We tried to contact the authors by e-mail, but we received no reply. Fifth, we performed Begg’s test and Egger’s test for publication bias assessment, and the results indicated potential publication bias.

In view of the limitations above, we recommend that non-English language literature should be included in future systematic meta-analyses. Furthermore, blind outcome assessments, use of target animal models (hypertensive, advanced age and diabetic), calculation of sample size, statement of compliance with animal welfare regulations, possible conflicts of interest and detailed data publishing should be considered in future animal model studies.

Conclusions

From a methodological perspective, animal experiments should be standardly and appropriately designed and transparently reported. Acupuncture may play a potential role in ameliorating cognitive dysfunction in animal models. Furthermore, our findings indicates that acupuncture could protect neurons in animal models of vascular dementia through enhanced oxygen and glucose metabolism, as well as antioxidant and anti-apoptosis effects. Thus, this field should be further explored in vascular dementia clinical trials.

Additional files

PRISMA 2009 Checklist. (DOC 57 kb)

Search Strategies. (DOCX 12 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our gratitude to Professor Bo-Yi Liu, from Department of Acupuncture, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China, for revising the manuscript. And we thank American Journal Experts (AJE) for English language editing. This manuscript was edited for English language by American Journal Experts (AJE).

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province of China (no.LY16H270004 and no.LY13H270012); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81273822 and no.81503645). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- 2-VO

Bilateral common carotid artery occlusion

- 4-VO

4-vessel occlusion

- CI

Confidence interval

- EA

Electroacupuncture

- EO

Embolic occlusion

- MCAO

Middle cerebral artery occlusion

- SD

Sprague–Dawley

- SMD

Standard mean differences

- VD

Vascular dementia

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: ZL, ZYZ. Performed the experiments: QC, HHD, ZYZ. Analyzed the data: QC, HHD, ZYZ. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: ZYZ. Wrote the paper: ZL, ZYZ. Revised the manuscript: QC, ZL. Agreed with the manuscript’s results and conclusions: QC, HHD, ZL, ZYZ. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ze-Yu Zhang, Email: 411947628@qq.com.

Zhe Liu, Email: ssrsliu@163.com.

Hui-Hui Deng, Email: 1743246305@qq.com.

Qin Chen, Email: 948309450@qq.com.

References

- 1.Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, DeCarli C, Greenberg SM, Iadecola C, Launer LJ, et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42(9):2672–2713. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182299496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sahathevan R, Brodtmann A, Donnan GA. Dementia, stroke, and vascular risk factors: a review. Stroke. 2012;7:61–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2011.00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stern Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70191-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zieren N, Duering M, Peters N, Reyes S, Jouvent E, Hervé D, Gschwendtner A, et al. Education modifies the relation of vascular pathology to cognitive function: cognitive reserve in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34(2):400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Román GC. Vascular dementia may be the most common form of dementia in the elderly. J Neurol Sci. 2002;s203–204(1):7–10. doi: 10.1016/S0022-510X(02)00252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Brien JT, Thomas A. Vascular dementia. Lancet. 2015;386(10004):1698–1706. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00463-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Health, NCCFM. Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care. Nhs National Institute for Health & Clinical Excellence; 2006.

- 8.Rabinstein AA, Shulman LM. Acupuncture in clinical neurology. Neurologist. 2003;9(9):137–148. doi: 10.1097/00127893-200305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pendlebury ST, Rothwell PM. Prevalence, incidence, and factors associated with pre-stroke and post-stroke dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(11):1006–1018. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macleod MR, O'Collins T, Howells DW, Donnan GA. Pooling of animal experimental data reveals influence of study design and publication bias. Stroke. 2004;35(5):1203–1208. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000125719.25853.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, Tang CZ, Lai XS. Effects of electroacupuncture on learning, memory and formation system of free radicals in brain tissues of vascular dementia model rats. J Tradit Chin Med. 2004;24(2):140–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu J, Liu C, Zhang X, Han J. Acupuncture improved cognitive impairment caused by multi-infarct dementia in rats. Physiol Behav. 2005;86(4):434–441. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shao Y, Fu Y, Qiu L, Yan B, Lai XS, Tang CZ. Electropuncture influences on learning, memory, and neuropeptide expression in a rat model of vascular dementia. Neural Regen Res. 2008;3(3):267–271. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang T, Liu CZ, Yu JC, Jiang W, Han JX. Acupuncture protected cerebral multi-infarction rats from memory impairment by regulating the expression of apoptosis related genes bcl-2 and bax in hippocampus. Physiol Behav. 2008;96(1):155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei D, Jia X, Yin X, Jiang W. Effects of electroacupuncture versus nimodipine on long-term potentiation and synaptophysin expression in a rat model of vascular dementia. Neural Regen Res. 2011;06(30):2357–2361. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao L, Shen P, Han Y, Zhang X, Nie K, Cheng H, et al. Effects of acupuncture on glycometabolic enzymes in multi-infarct dementia rats. Neurochem Res. 2011;36(5):693–700. doi: 10.1007/s11064-010-0378-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu Y, Zeng Y. Electroacupuncture protected pyramidal cells in hippocampal ca1 region of vascular dementia rats by inhibiting the expression of p53 and noxa. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2011;17(6):599–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00192.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu Y, Wang X, Ye X, Gao C, Wang W. Effects of electroacupuncture on the expression of p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase and ribosomal protein S6 in the hippocampus of rats with vascular dementia. Neural Regen Res. 2012;7(3):207–211. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu Y, Zeng Y, Wang X, Ye X. Effect of electroacupuncture on the expression of mTOR and eIF4E in hippocampus of rats with vascular dementia. Neurol Sci. 2013;34(7):1093–1097. doi: 10.1007/s10072-012-1209-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Junli, Litscher Gerhard, Li Haitao, Guo Wenhai, Liang Zhang, Zhang Ting, Wang Weihua, Li Xiaoyan, Zhou Yao, Zhao Bing, Rong Qi, Sheng Zemin, Gaischek Ingrid, Litscher Daniela, Wang Lu. The Effect of Scalp Point Cluster-Needling on Learning and Memory Function and Neurotransmitter Levels in Rats with Vascular Dementia. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2014;2014:1–5. doi: 10.1155/2014/294103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang X, Wu B, Nie K, Jia Y, Yu J. Effects of acupuncture on declined cerebral blood flow, impaired mitochondrial respiratory function and oxidative stress in multi-infarct dementia rats. Neurochem Int. 2014;65(1):23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li F, Yan CQ, Lin LT, Li H, Zeng XH, Liu Y, et al. Acupuncture attenuates cognitive deficits and increases pyramidal neuron number in hippocampal ca1 area of vascular dementia rats. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015. 10.1186/s12906-015-0656-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Li QQ, Shi GX, Yang JW, Li ZX, Zhang ZH, He T, et al. Hippocampal cAMP/PKA/CREB is required for neuroprotective effect of acupuncture. Physiol Behav. 2015. 10.1016/j.physbeh. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Wang Xue-Rui, Shi Guang-Xia, Yang Jing-Wen, Yan Chao-Qun, Lin Li-Ting, Du Si-Qi, Zhu Wen, He Tian, Zeng Xiang-Hong, Xu Qian, Liu Cun-Zhi. Acupuncture ameliorates cognitive impairment and hippocampus neuronal loss in experimental vascular dementia through Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2015;89:1077–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.10.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fang Y, Sui R. Electroacupuncture at the WANGU acupoint suppresses expression of inflammatory cytokines in the Hippocampus of rats with vascular dementia. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2016;13(5):17–24. doi: 10.21010/ajtcam.v13i5.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H, Liu Y, Lin LT, Wang XR, Du SQ, Yan CQ, et al. Acupuncture reversed hippocampal mitochondrial dysfunction in vascular dementia rats. Neurochem Int. 2015;92:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moher David, Liberati Alessandro, Tetzlaff Jennifer, Altman Douglas G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang KY, Liang S, Yu ML, Fu SP, Chen X, Lu SF. A systematic review and meta-analysis of acupuncture for improving learning and memory ability in animals. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016 Aug 19. 10.1186/s12906-016-1298-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Venkat Poornima, Chopp Michael, Chen Jieli. Models and mechanisms of vascular dementia. Experimental Neurology. 2015;272:97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Senn SJ. Overstating the evidence – double counting in meta-analysis and related problems. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Harris R, Bradburn M, Deeks J, Harbord R, Altman D, Steichen T, et al. Metan: stata module for fixed and random effects meta-analysis. Stat Softw Components. 2006;8(1):3–28.

- 32.Harris RJ, Bradburn MJ, Deeks JJ, Harbord RM, Altman DG, Sterne JAC. Metan: fixed- and random-effects meta-analysis. Stata J. 2008;8(1):3–28.

- 33.Palmer TM, Sterne JAC. Meta-analysis in Stata. Systematic reviews in health care: meta-analysis in context, second edition. BMJ publishing. Group. 2001:347–69.

- 34.Sterne J. A C, Egger M., Smith G. D. Systematic reviews in health care: Investigating and dealing with publication and other biases in meta-analysis. BMJ. 2001;323(7304):101–105. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7304.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahmed I., Sutton A. J., Riley R. D. Assessment of publication bias, selection bias, and unavailable data in meta-analyses using individual participant data: a database survey. BMJ. 2012;344(jan03 1):d7762–d7762. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qi Sihua, Mizuno Makoto, Yonezawa Kazuyoshi, Nawa Hiroyuki, Takei Nobuyuki. Activation of mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in spatial learning. Neuroscience Research. 2010;68(2):88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leung Mason Chin Pang, Yip Ka Keung, Ho Yuen Shan, Siu Flora Ka Wai, Li Wai Chin, Garner Belinda. Mechanisms Underlying the Effect of Acupuncture on Cognitive Improvement: A Systematic Review of Animal Studies. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 2014;9(4):492–507. doi: 10.1007/s11481-014-9550-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bekinschtein Pedro, Katche Cynthia, Slipczuk Leandro N., Igaz Lionel Müller, Cammarota Martín, Izquierdo Iván, Medina Jorge H. mTOR signaling in the hippocampus is necessary for memory formation. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2007;87(2):303–307. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi GX, Li QQ, Yang BF, Liu Y, Guan LP, Wu MM, et al. Acupuncture for Vascular Dementia: A Pragmatic Randomized Clinical Trial. Sci World J. 2015;(4):161439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PRISMA 2009 Checklist. (DOC 57 kb)

Search Strategies. (DOCX 12 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.