Version Changes

Revised. Amendments from Version 1

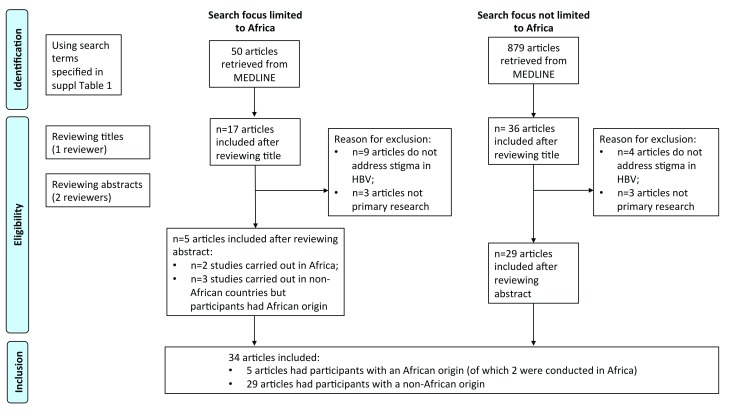

The new version of our article includes an improved description of the nature of the 'blind spot', setting out a number of reasons why we have introduced this metaphor for HBV stigma. The revision includes a PRISMA flow-chart as a main figure panel (previously included as supplementary data), and makes a clear distinction between the outcome of our systematic review of literature surrounding HBV (presented in the results section), vs. triangulation with data from other diseases associated with stigma (presented as discussion points). Each article identified was appraised by two independent reviewers, and we revised our results tables in order to provide a comprehensive summary of all the data collected from these articles, such that any given point might be linked to multiple citations, thereby adding confidence to the findings. We added a table to the results section to summarise the 32 papers that were identified, and grouped these by geographical area in order to provide a clearer snapshot of the existing literature, as well as highlighting specifically the lack of data for Africa. We undertook a quality appraisal of the literature to provide a better insight into the nature of the existing evidence. We amended the discussion to mention the potential association between stigma and physical disease manifestations.

Abstract

Background: Stigma, poverty, and lack of knowledge present barriers to the diagnosis and treatment of chronic infection, especially in resource-limited settings. Chronic Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is frequently asymptomatic, but accounts for a substantial long-term burden of morbidity and mortality. In order to improve the success of diagnostic, treatment and preventive strategies, it is important to recognise, investigate and tackle stigma. We set out to assimilate evidence for the nature and impact of stigma associated with HBV infection, and to suggest ways to tackle this challenge.

Methods: We carried out a literature search in PubMed using the search terms ‘hepatitis B’, ‘stigma’ to identify relevant papers published between 2007 and 2017 (inclusive), with a particular focus on Africa.

Results: We identified a total of 32 articles, of which only two studies were conducted in Africa. Lack of knowledge of HBV was consistently identified, and in some settings there was no local word to describe HBV infection. There were misconceptions about HBV infection, transmission and treatment. Healthcare workers provided inaccurate information to individuals diagnosed with HBV, and poor understanding resulted in lack of preventive measures. Stigma negatively impacted on help-seeking, screening, disclosure, prevention of transmission, and adherence to treatment, and had potential negative impacts on mental health, wellbeing, employment and relationships.

Conclusion: Stigma is a potentially major barrier to the successful implementation of preventive, diagnostic and treatment strategies for HBV infection, and yet we highlight a ‘blind spot’, representing a lack of data and limited recognition of this challenge. There is a need for more research in this area, to identify and evaluate interventions that can be used effectively to tackle stigma, and to inform collaborative efforts between patients, clinical services, policy makers, traditional healers, religious leaders, charity organisations and support groups.

Keywords: hepatitis B virus, discrimination, stigma, barriers, ethics, funding, elimination, Africa

Abbreviations

• PMTCT – Prevention of mother to child transmission

• TB – Tuberculosis

• HBV – Hepatitis B virus

• HCC – Hepatocellular carcinoma

• WHO – World Health Organization

• HIV – Human Immunodeficiency Virus

• HCWs – Healthcare workers

• THs – Traditional healers

• CHB – Chronic Hepatitis B

Introduction

Stigma is recognised as a challenge in association with many infectious diseases, but has been poorly studied and is inadequately recognised for viral hepatitis infections. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection has been reported worldwide, with an estimated burden of 250–290 million cases, and has been associated with high mortality rates resulting from complications including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) 1, 2. There are effective prevention and treatment strategies available, including vaccination and suppressive antiviral therapy, both of which also contribute to prevention of vertical transmission 3. The Global Hepatitis Health Sector Strategy is aiming for the elimination of viral hepatitis as a public health threat by 2030 4. However, stigma, poverty, and lack of knowledge can be significant barriers to diagnosis, treatment and prevention, especially in resource-limited settings 3. These issues sit alongside additional challenges including gaps in vaccine coverage 2, 5, limited provision of diagnostic tests and treatment 2 and lack of a curative therapy 3, 5. There is a growing body of personal testimonies providing evidence of stigma associated with HBV 6, 7. However, there is a very limited literature to describe this. We have therefore used the metaphor of a ‘blind spot’ to describe the current situation for HBV stigma. This reflects a genuine gap in culture or society in which there is no word for the infection, it highlights the paucity of published data, and it describes a problem that is known to exist, but which is often neglected or ignored by current interventions, policy and practice. In light of this, more work is required to understand the nature and impact of stigma for individuals with HBV infection.

Individuals who are stigmatised as a result of illness or infection not only have to contend with potential challenges to health, but may also be denied the opportunities that define quality of life such as education, employment, access to appropriate health care and interaction with a diverse cross-section of society 8. Although many diseases are stigmatised, awareness of – and investigation into – stigma is better represented in some areas than others. For example, in HIV, stigma has been shown to limit engagement with services including screening and prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT), and uptake of antiretroviral therapy 9– 12; in tuberculosis (TB) it has been shown to cause diagnostic delays and treatment non-compliance 13, 14, and in mental illness, stigma has been associated with delays in help-seeking, discontinuation of treatment, suboptimal therapeutic relationships, patient safety concerns, and poorer quality mental and physical care 15– 17.

Stereotypes and prejudice may stem from physical differences attributable to the condition, misconceptions associated with fear of contagion, and judgements about routes of transmission, all of which may be underpinned by lack of knowledge 18– 20 and stigma is enhanced by poor of awareness, education and perception 21. The importance of physical signs of illness is exemplified for HIV, where those displaying wasting syndrome and certain identifiable opportunistic infections have been described as suffering more stigma compared to those who are asymptomatic 9. HIV and TB may also be stigmatised as a result of anxieties about spread of infection, and may be regarded as a punishment for ‘irresponsible’ or ‘immoral’ behaviour, 14, 22– 24. People with mental illnesses may be considered ‘dangerous’ or provoke fear, may lose their autonomy, or be treated as ‘childlike’ 8. Understanding why society reacts in a particular way is one way to address stigma 19, and could therefore help to guide approaches to tackling stigma in HBV.

HBV infection is highly endemic in Africa, but there are huge challenges in prevention, diagnosis and treatment 2. The situation is further complicated by the substantial public health challenge of co-endemic HIV and HBV 25. An understanding of the breadth and scope of stigma in HBV, especially in Africa, is an essential part of any strategy that seeks to tackle and eventually eliminate HBV infection as a public health problem. As the improvement of universal availability and accessibility of diagnostic, treatment and vaccination options are underway, it is important to ensure that products and services are not only available, but also accessible; people with HBV infection must be able to access education, clinical care, and support from their partners and families, healthcare workers, and members of their communities. The WHO recommends HBV treatment in an environment that minimizes stigma and discrimination 26.

We set out to assimilate evidence for the nature and impact of stigma on the lives of people with HBV infection and on the community, to describe coping strategies employed by people with HBV, and to suggest ways to tackle stigma and discrimination. Our approach was to gather relevant information regarding HBV stigma from the published literature using a systematic approach, to curate it in order to unify key messages, and to highlight gaps where future work is still needed. We have been able to develop suggestions to address HBV stigma and discrimination from the existing literature, but in light of the paucity of HBV-specific studies, we have also triangulated our approach by drawing on resources from other stigmatised conditions including HIV, TB and mental illness to inform the discussion.

Methods

Search strategy: systematic literature review

In November-December 2017, we undertook a systematic literature search in PubMed; our search strategy focused entirely on the evidence detailing stigma in HBV ( Figure 1). The terms of this search are detailed in Supplementary file 1. We carried out two searches: the first search focused on stigma in HBV in Africa, and a second search was not limited to Africa. The two searches yielded 50 and 879 articles, respectively (n=929). We removed 49 duplicate articles (n=880). On reviewing the titles and abstracts, 827 were excluded from search results as they were not on stigma or HBV. Full texts of 53 articles were reviewed by two different individuals, and 19 were excluded (6 articles not primary studies and 13 articles do not address stigma in HBV). A total of 34 articles were therefore downloaded in full. From each publication, we extracted the following: citation, study design, sample size, study population, country, factors associated with stigma, impact of stigma on the lives of people with HBV, and proposed interventions to tackle stigma in the society. We used our research question to group data collated from the included studies into four major themes: factors underpinning stigma in HBV infection, evidence for the impact of stigma, coping strategies for individuals with HBV infection, and interventions proposed to tackle stigma in HBV. There were insufficient data from Africa to focus specifically on that continent, but where possible we have highlighted issues that have been reported in African populations. Data were curated using MS Excel software (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Ethics approval was not required for this study.

Figure 1. Flow diagram illustrating identification and inclusion of studies for a systematic review of stigma in HBV, based on PRISMA criteria.

Search strategy: other relevant resources

In order to inform a wider understanding of the potential relevance and impact of stigma in infection and illness, we have also referred to articles published on other conditions including HIV, TB and mental health to underpin hypotheses set out in the introduction, and to inform discussion. These papers were not identified through a formal systematic review, but were identified as relevant sources from robust, peer reviewed literature.

Quality of evidence assessment

For the 32 studies included from our systematic review, we performed a risk of bias assessment ( Supplementary file 2). For qualitative studies (n=12) we used the qualitative appraisal checklist by NICE public health guidance 27 and for quantitative studies (n=19) we used the Centre of Evidence based Management checklist 28. One study used a mixed method study design 29, and we assessed this using each of the two approaches above.

Results

A full list of citations generated from our systematic literature review of HBV stigma is shown in Table 1. We have also provided an expanded version of this table, with details summarising the key information pertinent to stigma, in Supplementary file 2.

Table 1. Characteristics of 32 studies identified using a systematic literature search for stigma in HBV.

| Citation (Author; Date; PMID),

divided by region of origin and presented alphabetically by first author |

Country where

study took place |

Study design | Study participants | Sample size | Recruitment

site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFRICA | |||||

| Adjei

et al. 2017; PMID:

29102991 30 |

Ghana | Qualitative | People with HBV infection | 14 | Hospital |

| Mkandawire

et al. 2013; PMID:

23811012 31 |

Ghana | Qualitative | Local chiefs, village elders

and HCWs |

72 | Community |

| NORTH AMERICA | |||||

| Blanas

et al. 2015; PMID:

25000917 32 |

USA | Qualitative | West African Immigrants | 39 | Community |

| Carabez

et al. 2014; PMID:

24395631 33 |

USA | Survey | HBV positive Asian

Americans |

154 | Community |

| Cheng

et al. 2017; PMID:

27770375 34 |

USA | Survey | Asian | 404 | Community |

| Cotler

et al. 2012; PMID:

22239504 35 |

USA | Survey | Chinese immigrants | N/A | Community |

| Frew

et al. 2014; PMID:

25506280 36 |

USA | Survey | Vietnamese Americans | 316 | Community |

| Li et al. 2007; PMID: 22993729 37 | Canada | Survey | Canadian Chinese | 343 | Community |

| Russ

et al. 2012; PMID:

22440043 38 |

USA | Qualitative | Asian Americans | HCWs:23

Individuals with HBV: 17 |

Hospital |

| Wu et al. 2009; PMID: 19172206 39 | Canada | Survey | People with HBV infection | 204 | Community |

| Yoo et al. 2012; PMID: 21748476 40 | USA | Qualitative | Asian American | 23 | Community |

| EUROPE | |||||

| Cochrane

et al. 2016; PMID:

26896472 41 |

UK | Qualitative | Somali community living in

UK |

30 | Community |

| Lee

et al. 2017; PMID:

28950835 42 |

UK | Qualitative | Chinese immigrants | 61 | Community |

| Sweeney

et al. 2015, PMID:

25890125 43 |

UK | Qualitative | Immigrant communities and

HCWs |

118 | Community

and healthcare centres |

| van der Veen

et al. 2014; PMID:

23913128 44 |

Netherlands | Survey | Turkish-Dutch community | N/A | Community |

| MIDDLE EAST AND ASIA | |||||

| Dam

et al. 2016; PMID:

28101498 45 |

Vietnam and USA | Survey | General population | 1012 | Hospital |

| Eguchi

et al. 2013; PMID:

24086765 46 |

Japan | Survey | Japanese working community | 3129 | Community |

| Eguchi

et al. 2014; PMID:

24792095 47 |

Japan | Survey | General population | 3000 | Community |

| Huang

et al. 2016; PMID:

27206379 48 |

China | Survey | Individuals with HBV and

healthy controls |

1236 | Community |

| Ishimaru

et al. 2016; PMID:

27108645 49 |

Japan | Survey | Nurses | 992 | Hospital |

| Ishimaru

et al. 2017; PMID:

29165125 50 |

Vietnam | Survey | Nurses | 400 | Hospital |

| Leng

et al. 2016; PMID:

27043963 51 |

China | Survey | General population | 903 | Community |

| Mohammed

et al. 2012; PMID:

22856889 52 |

Malaysia | Survey | People with HBV infection | 483 | Hospital |

| Ng et al. 2013; PMID: 21807630 53 | Malaysia | Qualitative study | People with HBV infection | 44 | Hospital |

| Rafique

et al. 2015; PMID:

25664518 54 |

Pakistan | Quantitive and

qualitative study |

People with HBV infection | 140 | Hospital |

| Taheri Ezbarami

et al. 2017;

PMID: 29085657 55 |

Iran | Qualitative study | People with HBV infection | 27 | Community |

| Valizadeh

et al. 2016; PMID:

26989666 56 |

Iran | Qualitative study | People with HBV infection | 18 | Hospital |

| Valizadeh

et al. 2017; PMID:

28362662 57 |

Iran | Qualitative study | People with HBV infection | 15 | Hospital |

| Wada

et al. 2016; PMID:

26850002 58 |

Japan | Survey | Nurses | 992 | Hospital |

| Wai et al. 2005; PMID: 16124053 59 | Singapore | Survey | People with HBV infection | 192 | Community |

| Wallace

et al. 2017; PMID:

28764768 60 |

China | Qualitative study | People with HBV infection | 41 | Hospital |

| Yu et al. 2015; PMID: 26733133 61 | China | Survey | General population | 6538 | Community |

| AUSTRALIA | |||||

| Drazic

et al. 2013; PMID:

23171324 62 |

Australia | Survey | General population | 77 | Community |

| Sievert

et al. 2017; PMID:

28120131 29 |

Australia | Survey | Afghan, Rohingyan and

Sudanese community |

26 | Community |

HBV = hepatitis B virus, HCW = healthcare worker

Quality of evidence

Asia and North America were best represented by the literature, in contrast to Africa from where we identified only two published studies, both set in Ghana ( Table 1). Among the 19 studies that used a quantitative study design, eight used a convenient sampling method which introduces selection bias 33– 35, 37, 45, 51, 59, 62, two studies did not describe a sampling method 39, 58, five used a random sampling method 36, 46, 47, 50, 61, three studies included all intended participants 44, 49, 52, and only one study used a sample size based on pre-study consideration 47. A participant response rate was presented in 10 studies; in nine of these the response rate was >60% 35– 37, 45, 49– 52, 59 and one had a 30% response rate 44. Statistical significance of results was reported in 15/19 studies 34– 37, 39, 44– 48, 51, 52, 59, 62.

All the qualitative studies described how concepts and themes were derived, presented findings clearly using extracts from original data and their findings were relevant to the research question 30– 32, 40– 43, 53– 56, 60. All except two of these 40, 41 clearly described data collection procedure and the research context. Analysis of data may be less robust in four studies 41, 42, 55, 56 since there was no description of how many researchers analysed the results and how differences in extracted themes and codes were resolved between researchers. Two studies did not provide details of ethics approval 40, 42; three studies did not provide a rationale for using the selected study methodology 40, 43, 60; seven studies did not report in detail on their study limitations 29, 42, 43, 53, 55, 56, 60. For the single study that used mixed methodology 29, a convenient sample was used. Participants’ response rate and statistical significance of quantitative data was not reported. In the qualitative arm, data collection and analysis was clearly described but it was not stated how many researchers analysed the data and how discrepancies were handled.

There was considerable diversity in the size of the population sampled (range 14–6538), but overall, most studies had small sample sizes (median 173), and some were opportunistic in recruiting participants, thus limiting the generalisability of the findings.

Themes

The data that we assimilated from our literature review of 32 systematically identified studies are presented in Table 2– Table 4 below.

Table 2. Factors underpinning stigma in HBV infection, identified from a systematic literature review.

| Factor underpinning stigma | Evidence from systematic literature review |

|---|---|

|

Cultural understanding and relevant

language |

• Lack of common cultural understanding of HBV is indicated by an absence of any word

in local languages to define HBV 31, 41 and missing terms ‘hepatitis B’ and ‘carcinoma’ from English vocabulary in migrant populations 29, 41; • There is confusion between HBV and other infections, including malaria, yellow fever and HIV 31, 32; HBV may be seen as synonymous with ‘jaundice’ 29, 41, 43, or believed to be associated with nutritional status 41; • One study describes the assumption that hepatitis A, B and C infections are ranked by letter in order of severity, or represent the chronological development of a single infection 43. |

|

Knowledge about diagnosis,

treatment and symptoms of chronic HBV infection |

• Poor understanding of the chronic nature of HBV infection, and lack of insight into the

asymptomatic nature of HBV infection and its complications, are well described 32, 39, 42, 43, 53, 59; • There may be an assumption that lack of symptoms correlates with lack of severity 29; • Poor awareness of treatment options can be associated with a ‘passive’ or ‘fatalistic’ attitude towards treatment 32, 53; • There are misconceptions that HBV screening tests can be harmful and that HBV infection is not treatable 36; • A significant correlation is reported between less knowledge and higher stigma scores 34. However, among individuals with HBV infection, higher levels of HBV knowledge can also be associated with being more worried 32, 41, 52; • Improved knowledge of HBV infection is associated with higher levels of formal education 39, 52, 59, 61, and with a close relationship with an individual infected with HBV 35. |

|

Beliefs and insights into

transmission of HBV infection |

• Beliefs are widespread that HBV can be transmitted through sharing of utensils, via food

and water, or eating together 33– 35, 37, 39, 41, 43, 45, 48, 51– 53, 59; • There is a belief that smoking tobacco causes HBV 36; • Some studies report beliefs that HBV infection arises as a result of poor sanitation 41, 43 or could be transmitted by sharing water for bathing 46; • In some communities, HBV infection is regarded as a genetic trait 34, 56; • HBV infection is represented as a consequence of immoral behaviour 40, 42– 44, or as a punishment for sins 55; • Some communities believe that HBV infection is caused by witchcraft or evil spirits; this can be associated with pursuit of traditional remedies or religious interventions 29– 31; • Poor insights into transmission are associated with lack of precautions for prevention of transmission 35, 56; • Awareness of injecting drug use and sexual transmission of HBV can be stigmatising 32, 42. |

| Sociodemographic factors | • In some studies older age has been associated with increased stigma

45,

48,

61; however, this is

not consistent, as older age has also been associated with decreased levels of stigma 47; • People strongly defined by traditional values are more likely to stigmtise HBV infection 55; • Unemployed individuals from rural areas are more likely to experience discrimination 51, 60; • HBV may be more prevalent in disadvantaged groups who are also stigmatised for other reasons, eg refugees 29; • Stigma can be reduced by having a family member with HBV infection; in this case it clarifies misconceptions about the disease, humanizes the affected, and can reduce negative attitudes associated with cultural beliefs 34, 35. |

| Interactions with HCWs | • Lacking or inaccurate information may be provided by HCWs regarding HBV diagnosis

or treatment, including inappropriate reassurance, or overemphasis of potential complications 49, 53; • Some studies describe HCWs expressing discrimination or prejudice towards patients and/ or colleagues with HBV infection 46, 58, which may be more common among those who have poor knowledge or are unfamiliar with providing HBV care 49; • Diagnosis of HBV infection is presented as ‘bad news’ which can add to anxiety and stigma 53, 56; • Lack of screening or vaccination may be associated with stigma 34, although in contrast, HBV-related discrimination is also described as arising in association with diagnostic screening 51. |

| Emotional responses | • HBV infection can be associated with anxiety, fear and depression; see

Table 3 for further

details and references. |

Table 3. Evidence for the behavioural, psychological and social impact of HBV infection, identified from a systematic literature review.

| Factor with

impact on HBV infection |

Evidence from systematic literature review |

|---|---|

|

Access to

appropriate health care and treatment compliance |

• Stigma is associated with reduced uptake of opportunities for diagnostic screening and clinical care

35,

37,

38,

42,

48,

56,

57;

• There is a low rate of disclosure of HBV status among individuals with HBV to family, other acquaintances, and to HCWs due to fear of stigma 48, 55; • Stigma can lead to disengagement from treatment 49 and reduce treatment adherence 55; • Anxiety about treatment, or the cost of treatment (potentially not just for one individual but also for other family members), can lead to reluctance to seek clinical care and follow-up 32, 49, 60; • Treatment can be seen as futile 55; • Stigma can lead to negative experiences of health care such as being ‘labelled’, placed in physical isolation, or criticised by HCWs 55; • Stigma may influence the priorities of health professionals and commissioners, leading to certain health issues being addressed whilst others are ignored 42. |

|

Impact on

opportunities for education, work and career development |

• Discrimination is reported within schools

35,

45;

• HBV affects employment and education choices 48, 60; individuals with HBV infection may be discriminated against at work, lose employment, or be unable to find work 29, 34, 42, 54– 56, 60; they may also be concerned about missing work due to illness 33, and may be restricted from particular jobs (e.g. food preparation) 37, 52; • As a result of discrimination in education and the work-place, HBV can prevent personal goals or potential from being fulfilled 55. |

|

Impact on mental

health |

• People with HBV infection may fear physical consequences of transmission, disease progression and/or

treatment side effects 29, 51, 53, including fear of cancer and death 30, 33, 55, 56; • Individuals in migrant populations may fear deportation 32, 38; • A range of emotional responses is described, included shock and grief following initial diagnosis, and subsequently anxiety, sadness, denial, anger and aggression 30, 52, 56, 57, 62; • Negative self-image can be associated with infection, associated with feelings of disgrace, guilt and shame, humiliation, embarrassment, or inferiority 32, 34, 35, 39, 44, 48, 52, 53, 56; • Reactions can also include insomnia and depression 49, 53– 56, 60, and suicidal ideation 42, 54; • Anxiety is described in association with the economic cost of treatment 29; • A fear of disclosure promotes secrecy and isolation 55, 56, 60, 62. |

|

Impact on

personal interactions |

• ‘Fear of contagion’ causes isolation; individuals with infection either avoid or are rejected from social activities,

including avoidance of sharing utensils / food / towels / soap 35, 37, 42, 43, 48, 51, 53, 54, 56, 57, 60, and may be banned from participation in sports 55; • Parents may be unwilling to allow their children to socialise with HBV-infected children 51, 61; • Anxiety about spreading infection to family members leads to withdrawal from close relationships 29, 32, 35, 52, 53, 57; and exclusion from social gatherings 60; • Individuals with HBV infection perceive themselves, or are perceived by others, as less desirable as a parent or spouse 33– 35, 45, 48, 54; • Partner or spouse refuses sexual intercourse or insists on use of condoms 54; • Individuals with HBV infection may seek assistance from traditional healers (THs) or faith leaders, seeking ‘purification’; although this can provide important psychosocial support, there is also the potential for harm and/or delaying presentation to clinical care 30. |

Table 4. Interventions that have been used to tackle stigma in HBV, identified from a systematic literature review.

| Category of intervention | Evidence from systematic literature review |

|---|---|

|

Interventions targeting

individuals with HBV infection |

• Provision of educational opportunities in health care settings, in the individual’s own language,

can be valuable to inform patients of the importance of symptoms, treatment, follow-up, prevention and social stigma 32, 33, 43, 52; • Improving knowledge regarding the potential for silent complications, and understanding treatment could enhance willingness to access healthcare and reduce fatalism 32, 39; • Developing positive coping strategies may include seeking encouragement from spiritual leaders and open dialogue with family members 33, 43, 48, 55; • Lifestyle modifications can be helpful, such as reduced intake of alcohol and fatty foods 30, 33, 52; • Barriers to interventions should be considered (e.g. remote location, no internet access, language barriers) 62. |

|

Interventions targeting

HCWs |

• Education and training for HCWs should be improved, particularly for community

doctors in rural settings 61; this includes training in diagnosis, prevention, treatment and monitoring 31, 33, 35, 37, 49, 53, and provision of appropriate pre- and post-test counselling 29, 33, 49; • HCWs can be deployed to design interventions to encourage participation in treatment programs and better self-care 55; • Education and communication programmes are needed to reduce stigma towards patients and colleagues with HBV infection 49– 51; • Championing a positive safety culture, such as strict infection control, may not only protect HCWs but can also improve the quality of patient care 50. |

|

Interventions targeting

communities and policy makers |

• Culturally appropriate education programs are required to improve knowledge on symptoms,

modes of transmission and preventative measures, to correct misconceptions and decrease stigma; this could include use of internet, social media, radio, posters in public places (bars, markets, healthcare settings), and should involve schools and religious leaders 31– 36, 40, 41, 47– 49, 53, 55; • Specialised training on HBV for THs and ministers of faith could be a valuable approach 30; • Targeting individuals directly (e.g. with letters) might be of greater benefit than mass media campaigns 41; • Developing national campaigns to promote HBV screening and vaccination as positive strategies that can empower local communities in their own healthcare 40, 53; • Establishing a human connection can increase familiarity and reduce apprehension and negativity 42; for example, high profile public advocates have been successful in the ‘B Free Campaign’ 34, 40; • National strategic responses to HBV infection should specifically acknowledge and address the social implications of the infection 60, and should prioritise affordability of prevention and treatment 36. |

Discussion

Through this review, we have been able to identify some key themes including the potentially profound impact of HBV infection on personal wellbeing and mental health, opportunities for education and career, influence on family and relationships, and the role that health care workers can play in either contributing to stigma or dispelling it. Through enhancing consistent insights into these areas, the ‘blind spot’ associated with HBV stigma can start to be reduced. Previous reviews addressing stigma in Asian populations have reported small numbers of relevant publications, but identify the challenges of stigma, poor knowledge, and lack of focus on appropriate interventions 63, 64. This review demonstrates the lack of data for the whole of the African continent which is particularly striking. A recent report showed that in Africa, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) secondary to HBV infection frequently presents at a late stage, where effective treatment would be challenging for any healthcare system 34, and indeed presentation is too late to allow formal diagnosis or treatment – this illustrates a hidden burden of infection, another aspect of the ‘blind spot’.

Stigma associated with physical disease manifestations

In most cases, HBV infection is asymptomatic and invisible for many decades, so individuals are not likely to be physically stigmatised. However, in acute infection, and again in the latter stages of chronic disease, it may cause jaundice and other manifestations such as abdominal swelling from ascites. We have not found any representation in the literature of stigma associated with specific physical syndromes, but further work is needed to explore this possibility. Importantly, health-related quality of life, including mental health, has been shown to decline in the setting of more severe manifestations of HBV infection 65.

Relationship between stigma and knowledge or education

Findings in Africa demonstrate a general lack of knowledge on HBV, an inability to define the disease, confusion of HBV with other infections, including malaria, yellow fever and HIV 31, 32, and the association of HBV symptoms with witchcraft or poisoning 30, 31. Such negative associations have been described to have the potential to ‘spoil the identity’ of the individual: the individual ceases to be perceived as a normal person but rather one who is tainted and discounted from society 20. Lack of knowledge or awareness leads to misinformation that feeds stigma and discrimination 66. Formal education can be important in reducing discrimination and stigma 46; however, it is interesting to note that this is not always the case. Indeed, higher levels of knowledge or formal education can sometimes be associated with increased stigma 39, 46. One study describes how specific knowledge - such as recognising sexual contact as a transmission route – can actually increase stigma 32. In other settings, education level did not have a specific relationship with stigma 51. A general lack of stigma was reported associated with HBV in the Somali population, but this study reports that the problem of stigma is increasing over time as education increases 41.

Age may be relevant to knowledge or education, and varying influence of age on stigma has also been reported; in some instances older age and traditional values have been associated with stigma 45, 46, 53 while in others, there is decreased prejudice among older age 47. In light of these discrepancies, it is important to design studies with bigger sample sizes and conduct studies in different regions and communities. This will help to not only provide a clear explanation of factors associated with stigma in HBV but will also guide in designing interventions that target specific groups of people who might be most vulnerable to the effects of stigma.

Interventions for HBV stigma

Depending on the coping strategies used, not everyone experiencing stigma will necessarily suffer emotional distress or have diminished well-being as a consequence 67. In HIV, avoidant coping strategies such as denial have been associated with higher levels of depression whereas acceptance of the diagnosis, associated with personal control and self-efficacy, is associated with reduced levels of depression 68. Among patients with schizophrenia, the ability to use positive coping strategies was associated with reduced self-stigma 52. Stigma and/or the disease process can contribute to the decline of health-related quality of life and mental health of some individuals living with chronic HBV 65, however there are few studies that address these issues. In light of this, further studies are needed to explore coping strategies used to deal with HBV stigma, to explore the choice of coping strategy, and to determine outcomes.

As well as individual coping strategies, a variety of other interventions have been proposed to tackle stigma ( Table 3). In many cases, attitudes may improve after realising that infection can be prevented and managed therapeutically 37. This is in line with a report from the WHO about mental illness, highlighting that stigma can be combated through educational messages representing conditions as illnesses that respond to specific treatment 46. Counselling can provide several benefits, alleviating anxiety associated with a new diagnosis, as well as providing an opportunity to share factual information regarding treatment, prevention, self-care and overall well-being 33, 49. This should be delivered sensitively, at a time and in a manner that supports the individual in accepting and processing the information.

There are several strategies that have been used to raise awareness of HIV, many of which could be applied to HBV. Dissemination of factual information through use of radio, television, posters, pamphlets and drama has been widely used to diminish stigma towards HIV in resource limited settings 9. Multiple educational sessions can also be an effective way of increasing awareness and therefore reducing stigma, as participants have the opportunity to reflect on the concepts learnt in the previous sessions 58. Another successful method for training HCWs is perspective-taking and empathy: participation is associated with ‘increased willingness to treat people with certain illnesses, decreased stigma and increased awareness of confidentiality among healthcare workers’ 58. These approaches could be used to tackle HBV stigma among HCWs and community members.

On-line support groups provide a platform for people living with HBV to share their experiences 69, 70, and charities can be influential in raising awareness, and promoting important health messages 70. The internet is widely used as a tool for sharing experiences, and as such can raise awareness of stigma 7, as well as uniting individuals and communities as a support network. It is important for HCWs to introduce newly diagnosed individuals to these avenues to help people living with HBV. Importantly, more charities and support groups that are well suited for people with HBV infection in Africa are needed.

Limitations and caveats

Only two studies were identified on HBV stigma from Africa 30, 31; these studies were both carried out in one country (Ghana). Three other studies included African participants in USA 32, Australia 29 and in UK 41. This highlights the substantial problem of HBV neglect in Africa. However, although we undertook a robust systematic search of the peer-reviewed scientific literature, there may be other sources that are not captured by this scientific style of approach.

Sub-Saharan Africa encompasses huge diversity, and as such it would be misleading to assume that we can generalise about culture, beliefs and stigma, or that findings that arise in one setting can be extrapolated to others; the knowledge, manifestations, and experience of stigma is bound to be different between settings. It is frequently the case that local, indigenous knowledge and understanding of disease and/or health conditions is not well reflected in the published literature. Further work will be needed to develop insights that are relevant to particular populations in order to develop the most effective interventions. Referring to specific examples for particular places or countries is currently difficult in the absence of more published data. However, to understand some of the specific challenges of HBV, we have previously collated individual experiences of HBV from patients, researchers and healthcare workers representing different settings across sub-Saharan Africa 3.

Our description of ‘coping strategies’ is an over-simplification of the complex responses that arise as a result of stigma. We recognise that many individuals who suffer stigma may not be able to deploy specific active coping mechanisms, and indeed may ‘endure’ their situation.

Future aspiration and challenges

We see this article as a starting point for this field, as it is currently very difficult to make substantial advances in the absence of better data. By collating the existing literature, we hope to raise the profile of this topic overall, to improve recognition of the problem, to promote dialogue, and to highlight specific areas of neglect. This provides a foundation for healthcare workers and researchers to build on over time.

Studies looking at stigma may benefit from a mixed method study design, providing stronger evidence and increasing generalisability of the findings. It is important to carry out research on stigma with the aim of demonstrating its burden and its effects, while also considering how to establish and evaluate interventions that tackle stigma within communities. We identified only one study that evaluated the effectiveness of stigma reduction programmes among Asians in USA 40. More studies like this are needed in Africa, in order to provide insights into local understanding and beliefs, as they will also help to deploy resources in the most appropriate and effective ways with particular relevance to individual settings. In addition to raising awareness among individuals with HBV infection, the general public and HCWs, enhanced communication with policy makers is also crucial. Despite the high burden of HBV in low and middle-income countries, there is limited infrastructure to support diagnosis and treatment, and disproportionately little international research funding for HBV compared to other infectious diseases 3.

Conclusion

Despite the limited evidence from Africa, the data we have gathered reflect consistent themes in stigma and discrimination affecting individuals with chronic viral hepatitis infection. These may have a wide-reaching influence on physical health (for example inhibiting interaction with clinical services and reducing treatment adherence), psychological well-being (through increasing isolation, anxiety and depression), and interactions with family and the wider society (by limiting relationships, social interactions and employment opportunities). Recognising, understanding and tackling the issue of this stigma in African populations could be a valuable tool to improve population health and to underpin advances towards elimination strategies proposed for the year 2030. Education clearly provides a very important role in reducing discrimination and stigma; it is interesting to note that stigma may drive lack of knowledge, just as lack of knowledge may drive stigma.

There is also a pressing need for more research in this area, to identify and evaluate interventions that can be used effectively to tackle stigma in HBV, and for collaborative efforts between policy makers, HCWs, traditional healers, religious leaders, charity organisations and support groups, to improve awareness and tackle stigma in HBV in Africa.

Data availability

All data underlying the results are available as part of the article and Supplementary files, and no additional source data are required.

Funding Statement

JM is funded by a Leverhulme Mandela Rhodes Scholarship. PCM is funded by the Wellcome Trust (grant ref. 110110).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 2; referees: 2 approved]

Supplementary material

Supplementary file 1: Details of search strategy used to identify studies on stigma in Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, from PubMed database. The terms in each row were combined by Boolean operator ‘OR’, the columns were combined by Boolean term ‘AND’. We carried out two searches: the first search focused on stigma in HBV in Africa - we combined all the columns in search strategy (#1 AND #2 AND #3); a second search was not limited to Africa – for this we only combined columns (#1 AND #3).

Supplementary file 3. Details of risk of bias assessment, using Centre of Evidence based management checklist, on 14 quantitative studies identified by a systematic literature search of stigma in Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection published between 2005 and 2017.

Supplementary file 4. Details of risk of bias assessment, using NICE public health guidance qualitative appraisal checklist, on 20 quantitative studies identified by a systematic literature search of stigma in Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection published between 2005 and 2017.

References

- 1. Polaris Observatory Collaborators: Global prevalence, treatment, and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in 2016: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(6):383–403. 10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30056-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization: Global Hepatitis Programme. Global hepatitis report,2017;68 Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 3. O’Hara GA, McNaughton AL, Maponga T, et al. : Hepatitis B virus infection as a neglected tropical disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(10):e0005842. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. WHO: Global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis 2016-2021. WHO.2017. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jooste P, van Zyl A, Adland E, et al. : Screening, characterisation and prevention of Hepatitis B virus (HBV) co-infection in HIV-positive children in South Africa. J Clin Virol. 2016;85:71–4. 10.1016/j.jcv.2016.10.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hepatitis B organisation. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stigma around Hepatitis B infection. The Hippocratic Post. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 8. Corrigan PW, Watson AC: Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry. 2002;1(1):16–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mahajan AP, Sayles JN, Patel VA, et al. : Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS. 2008;22 Suppl 2:S67–79. 10.1097/01.aids.0000327438.13291.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, et al. : HIV stigma mechanisms and well-being among PLWH: a test of the HIV stigma framework. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(5):1785–95. 10.1007/s10461-013-0437-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Turan JM, Nyblade L: HIV-related stigma as a barrier to achievement of global PMTCT and maternal health goals: a review of the evidence. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(7):2528–39. 10.1007/s10461-013-0446-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, et al. : Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(3 Suppl 2):18640. 10.7448/IAS.16.3.18640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Craig GM, Daftary A, Engel N, et al. : Tuberculosis stigma as a social determinant of health: a systematic mapping review of research in low incidence countries. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;56:90–100. 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Courtwright A, Turner AN: Tuberculosis and stigmatization: pathways and interventions. Public Health Rep. 2010;125 Suppl 4:34–42. 10.1177/00333549101250S407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Knaak S, Mantler E, Szeto A: Mental illness-related stigma in healthcare: Barriers to access and care and evidence-based solutions. Healthc Manage Forum. 2017;30(2):111–6. 10.1177/0840470416679413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Livingston JD, Boyd JE: Correlates and consequences of internalized stigma for people living with mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(12):2150–61. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Corrigan PW, Druss BG, Perlick DA: The Impact of Mental Illness Stigma on Seeking and Participating in Mental Health Care. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2014;15(2):37–70. 10.1177/1529100614531398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aljazeera: A curse in the family: Behind India’s witch hunts.India, Al Jazeera.2013. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 19. Skinner D, Mfecane S: Stigma, discrimination and the implications for people living with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. SAHARA J. 2004;1(3):157–64. 10.1080/17290376.2004.9724838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goffman E: STIGMA Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity.1990;10:8–7. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shrivastava A, Johnston M, Bureau Y: Stigma of Mental Illness-1: Clinical reflections. Mens Sana Monogr. 2012;10(1):70–84. 10.4103/0973-1229.90181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cremers AL, de Laat MM, Kapata N, et al. : Assessing the consequences of stigma for tuberculosis patients in urban Zambia. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119861. 10.1371/journal.pone.0119861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Baral SC, Karki DK, Newell JN: Causes of stigma and discrimination associated with tuberculosis in Nepal: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(1):211. 10.1186/1471-2458-7-211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Halli SS, Khan CG, Moses S, et al. : Family and community level stigma and discrimination among women living with HIV/AIDS in a high HIV prevalence district of India. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv. 2017;16(1):4–19. 10.1080/15381501.2015.1107798 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bivigou-Mboumba B, François-Souquière S, Deleplancque L, et al. : Broad Range of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Patterns, Dual Circulation of Quasi-Subgenotype A3 and HBV/E and Heterogeneous HBV Mutations in HIV-Positive Patients in Gabon. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0143869. 10.1371/journal.pone.0143869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. World Health Organization, Global Hepatitis Programme: Guidelines for the prevention, care, and treatment of persons with chronic hepatitis B infection.134 Reference Source [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance (third edition).Guidance and guidelines, NICE. Reference Source [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Centre of Evidence Based Mnagament: Critical appraisal for cross-sectional studies. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sievert K, O’Neill P, Koh Y, et al. : Barriers to Accessing Testing and Treatment for Chronic Hepatitis B in Afghan, Rohingyan, and South Sudanese Populations in Australia. J Immigr Minor Health. 2018;20(1):140–146. 10.1007/s10903-017-0546-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Adjei CA, Naab F, Donkor ES: Beyond the diagnosis: a qualitative exploration of the experiences of persons with hepatitis B in the Accra Metropolis, Ghana. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11):e017665. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mkandawire P, Richmond C, Dixon J, et al. : Hepatitis B in Ghana’s upper west region: a hidden epidemic in need of national policy attention. Health Place. 2013;23:89–96. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Blanas DA, Nichols K, Bekele M, et al. : Adapting the Andersen model to a francophone West African immigrant population: hepatitis B screening and linkage to care in New York City. J Community Health. 2015;40(1):175–84. 10.1007/s10900-014-9916-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Carabez RM, Swanner JA, Yoo GJ, et al. : Knowledge and fears among Asian Americans chronically infected with hepatitis B. J Cancer Educ. 2014;29(3):522–8. 10.1007/s13187-013-0585-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cheng S, Li E, Lok AS: Predictors and Barriers to Hepatitis B Screening in a Midwest Suburban Asian Population. J Community Health. 2017;42(3):533–43. 10.1007/s10900-016-0285-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cotler SJ, Cotler S, Xie H, et al. : Characterizing hepatitis B stigma in Chinese immigrants. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19(2):147–52. 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01462.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Frew PM, Alhanti B, Vo-Green L, et al. : Multilevel factors influencing hepatitis B screening and vaccination among Vietnamese Americans in Atlanta, Georgia. Yale J Biol Med. 2014;87(4):455–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li D, Tang T, Patterson M, et al. : The impact of hepatitis B knowledge and stigma on screening in Canadian Chinese persons. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26(9):597–602. 10.1155/2012/705094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Russ LW, Meyer AC, Takahashi LM, et al. : Examining barriers to care: provider and client perspectives on the stigmatization of HIV-positive Asian Americans with and without viral hepatitis co-infection. AIDS Care. 2012;24(10):1302–7. 10.1080/09540121.2012.658756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wu H, Yim C, Chan A, et al. : Sociocultural factors that potentially affect the institution of prevention and treatment strategies for prevention of hepatitis B in Chinese Canadians. Can J Gastroenterol. 2009;23(1):31–6. 10.1155/2009/608352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yoo GJ, Fang T, Zola J, et al. : Destigmatizing hepatitis B in the Asian American community: lessons learned from the San Francisco Hep B Free Campaign. J Cancer Educ. 2012;27(1):138–44. 10.1007/s13187-011-0252-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cochrane A, Collins P, Horwood JP: Barriers and opportunities for hepatitis B testing and contact tracing in a UK Somali population: a qualitative study. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26(3):389–95. 10.1093/eurpub/ckv236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lee ACK, Vedio A, Liu EZH, et al. : Determinants of uptake of hepatitis B testing and healthcare access by migrant Chinese in the England: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):747. 10.1186/s12889-017-4796-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sweeney L, Owiti JA, Beharry A, et al. : Informing the design of a national screening and treatment programme for chronic viral hepatitis in primary care: qualitative study of at-risk immigrant communities and healthcare professionals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:97. 10.1186/s12913-015-0746-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. van der Veen YJ, van Empelen P, Looman CW, et al. : Social-cognitive and socio-cultural predictors of hepatitis B virus-screening in Turkish migrants, the Netherlands. J Immigr Minor Health. 2014;16(5):811–21. 10.1007/s10903-013-9872-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dam L, Cheng A, Tran P, et al. : Hepatitis B Stigma and Knowledge among Vietnamese in Ho Chi Minh City and Chicago. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2016: 1910292. 10.1155/2016/1910292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Eguchi H, Wada K: Knowledge of HBV and HCV and individuals’ attitudes toward HBV- and HCV-infected colleagues: a national cross-sectional study among a working population in Japan. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e76921. 10.1371/journal.pone.0076921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Eguchi H, Wada K, Smith DR: Sociodemographic factors and prejudice toward HIV and hepatitis B/C status in a working-age population: results from a national, cross-sectional study in Japan. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96645. 10.1371/journal.pone.0096645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Huang J, Guan ML, Balch J, et al. : Survey of hepatitis B knowledge and stigma among chronically infected patients and uninfected persons in Beijing, China. Liver Int. 2016;36(11):1595–603. 10.1111/liv.13168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ishimaru T, Wada K, Arphorn S, et al. : Barriers to the acceptance of work colleagues infected with Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C in Japan. J Occup Health. 2016;58(3):269–75. 10.1539/joh.15-0288-OA [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ishimaru T, Wada K, Hoang HTX, et al. : Nurses’ willingness to care for patients infected with HIV or Hepatitis B / C in Vietnam. Environ Health Prev Med. 2017;22(1):9. 10.1186/s12199-017-0614-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Leng A, Li Y, Wangen KR, et al. : Hepatitis B discrimination in everyday life by rural migrant workers in Beijing. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(5):1164–71. 10.1080/21645515.2015.1131883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mohamed R, Ng CJ, Tong WT, et al. : Knowledge, attitudes and practices among people with chronic hepatitis B attending a hepatology clinic in Malaysia: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:601. 10.1186/1471-2458-12-601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ng CJ, Low WY, Wong LP, et al. : Uncovering the experiences and needs of patients with chronic hepatitis B infection at diagnosis: a qualitative study. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2013;25(1):32–40. 10.1177/1010539511413258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rafique I, Saqib MA, Siddiqui S, et al. : Experiences of stigma among hepatitis B and C patients in Rawalpindi and Islamabad, Pakistan. East Mediterr Health J. 2015;20(12):796–803. 10.26719/2014.20.12.796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Taheri Ezbarami Z, Hassani P, Zagheri Tafreshi M, et al. : A qualitative study on individual experiences of chronic hepatitis B patients. Nurs open. 2017;4(4):310–8. 10.1002/nop2.100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Valizadeh L, Zamanzadeh V, Negarandeh R, et al. : Psychological Reactions among Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B: a Qualitative Study. J caring Sci. 2016;5(1):57–66. 10.15171/jcs.2016.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Valizadeh L, Zamanzadeh V, Bayani M, et al. : The Social Stigma Experience in Patients With Hepatitis B Infection: A Qualitative Study. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2017;40(2):143–50. 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wada K, Smith DR, Ishimaru T: Reluctance to care for patients with HIV or hepatitis B / C in Japan. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:31. 10.1186/s12884-016-0822-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wai CT, Mak B, Chua W, et al. : Misperceptions among patients with chronic hepatitis B in Singapore. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(32):5002–5. 10.3748/wjg.v11.i32.5002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wallace J, Pitts M, Liu C, et al. : More than a virus: a qualitative study of the social implications of hepatitis B infection in China. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):137. 10.1186/s12939-017-0637-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yu L, Liu H, Zheng J, et al. : [Present situation and influencing factors of discrimination against hepatitis B patients and carriers among rural adults in three eastern provinces in China]. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2015;49(9):771–6. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2015.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Drazic YN, Caltabiano ML: Chronic hepatitis B and C: Exploring perceived stigma, disease information, and health-related quality of life. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(2):172–8. 10.1111/nhs.12009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lee H, Fawcett J, Kim D, et al. : Correlates of Hepatitis B Virus-related Stigmatization Experienced by Asians: A Scoping Review of Literature. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2016;3(4):324–34. 10.4103/2347-5625.195896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Vedio A, Liu EZH, Lee ACK, et al. : Improving access to health care for chronic hepatitis B among migrant Chinese populations: A systematic mixed methods review of barriers and enablers. J Viral Hepat. 2017;24(7):526–40. 10.1111/jvh.12673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Modabbernia A, Ashrafi M, Malekzadeh R, et al. : A review of psychosocial issues in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Arch Iran Med. 2013;16(2):114–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Colvin HM, Mitchell AE: Knowledge and Awareness About Chronic Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C.2010. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sriphanlop P, Jandorf L, Kairouz C, et al. : Factors related to hepatitis B screening among Africans in New York City. Am J Health Behav. 2014;38(5):745–54. 10.5993/AJHB.38.5.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yu L, Wang J, Zhu D, et al. : Hepatitis B-related knowledge and vaccination in association with discrimination against Hepatitis B in rural China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(1):70–6. 10.1080/21645515.2015.1069932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hepatitis B Support Groups.Online, DailyStrength. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hepatitis B Foundation. Reference Source [Google Scholar]