Abstract

Background

The Developmental, Individual-differences, Relationship-based model (DIR/Floortime) is one of the well-known therapies for autism spectrum disorder (ASD), in which its main principle is to promote holistic development of an individual and relationships between the caregivers and children. Parental engagement is an essential element to DIR/Floortime treatment and involved with various factors. Finding those supporting factors and eliminating factors that might be an obstacle for parental engagement are essential for children with ASD to receive the full benefits of treatment.

Aim

To examine the association between parents, children and provider and service factors with parental engagement in DIR/Floortime treatment.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study of parents with children aged 2–12 years who were diagnosed with ASD. Data were collected using a parent, child, provider and service factors questionnaire. Patient Health Questionaire-9, Clinical Global Impressions-Severity and Childhood Autism Rating Scale were also used to collect data. For parent engagement in DIR/Floortime, we evaluated quality of parental engagement in DIR/Floortime and parent application of DIR/Floortime techniques at home. Finally, Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement and Functional Emotional Developmental Level were used to assess child development.

Results

Parents who were married, had lower income and higher knowledge of DIR/Floortime theory were more likely to have higher parent engagement (χ2=4.43, p=0.035; χ2=13.1, p<0.001 and χ2=4.06, p=0.044 respectively). Furthermore, severity of the diagnosis and the continuation of the treatment significantly correlated with parent engagement (χ2=5.83, p=0.016 and χ2=4.72, p=0.030 respectively). It was found that parents who applied the techniques for more than 1 hour/day, or had a high-quality parent engagement, significantly correlated with better improvement in child development (t=−2.03, p=0.049; t=−2.00, p=0.053, respectively).

Conclusion

Factors associated with parents, children, and provider and service factors had a significant correlation with parent engagement in DIR/Floortime in which children whose parents had more engagement in DIR/Floortime techniques had better improvement in child development.

Keywords: parent engagement, DIR, floortime, autism spectrum disorder

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects one’s social interaction, communication skill, interest and behaviours.1 2 According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, it was found that the prevalence rate of ASD has increased from 3 to 4 in 10 000 children to 9 in 10 000 children in 2016 with a male-to-female ratio of 4:1.3 In Thailand, it has been shown that the prevalence of ASD in children between the ages of 1 year and 5 years is 9.9 in 10 000.4 Furthermore, later studies found that the prevalence increased to 1 in 250 children in Thailand, which may be due to an increase in prevalence or an increase in diagnosis now that there is more awareness surrounding ASD.5 The Ministry of Public Health stated in their most recent research that there are about 180 000 Thai children who have been diagnosed with ASD.6

One of the well-known forms of therapy for ASD is Developmental, Individual-differences, Relationship-based model (DIR/Floortime), which was created by Greenspan and colleagues. DIR’s main principle is to promote holistic development of an individual and relationships between the caregivers and children through three essential methods. First, Floortime is a technique that helps child development by having children and caregivers play or do activities together. Second, home-based practice is the time when parents/caregivers help children develop certain skills that might be a challenge for them. Finally, individual therapy sessions with therapists1 7 that help develop relationships between caregivers and children that benefit children’s communication, emotions, needs and logic.1 According to Pajareya and Nopmaneejumruslers,3 they found that after parents received DIR/Floortime training for 3 months, they were able to better help their children’s emotional and social development. Therefore, parental engagement in DIR/Floortime is an essential element for child improvement. Furthermore, there are various studies that show many parents’ related factors such as lower socioeconomic status family, knowledge, motivation, stress and attitudes towards treatment and their child affect parents’ involvement in the therapy.8–10 There is research about parents’ involvement in using applied behavioural analysis (ABA) on children with ASD aged 3–5 years. The results show various family factors (ie, the number of children, being a single parent, parents’ perspective towards the diagnosis) affect parent engagement in the ABA.11 Additionally, factors within the child are important as well, for example, if a child has severe ASD, it might negatively affect the parent–child relationship and lead to poor parental involvement.12 Furthermore, factors including the therapists and techniques they use also play a big role in parent engagement.13 14 Client perceptions of their therapists’ acceptance and understanding, commitment, motives to act in the clients’ best interests,15 compassion,16 empathy and interpersonal skills15 17 18 were all positively associated with participation, and if the techniques were too difficult, it could also affect parental engagement as well.19 As mentioned above, parent engagement is essential to various interventions for ASD children, and various factors are involved. There are many studies about parental factors related to involvement in ABA and pivotal response techniques. None of them study parent factors related to involvement in DIR/Floortime. Hence, it is crucial to acknowledge factors associated with parent engagement in DIR/Floortime treatment, which is our research question in this study. Our findings may be of help in supporting parental engagement in therapy and removing obstacles to their participation in the process.

Methods

Participants

This study was a cross-sectional survey with the following inclusion and exclusion criteria for the sample: inclusion criteria: (1) parents with children aged 2–12 years who were diagnosed with ASD and received more than three sessions of DIR/Floortime at the National Institute for Child and Family Development (NICFD); (2) children who were diagnosed with ASD by psychiatrists or paediatricians according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR)20 and (3) parents who were included must have to lived with their children for at least 1 year. Exclusion criteria were the following: (1) children who had a disability or were diagnosed with specific syndromes such as Down’s syndrome or Rett syndrome.

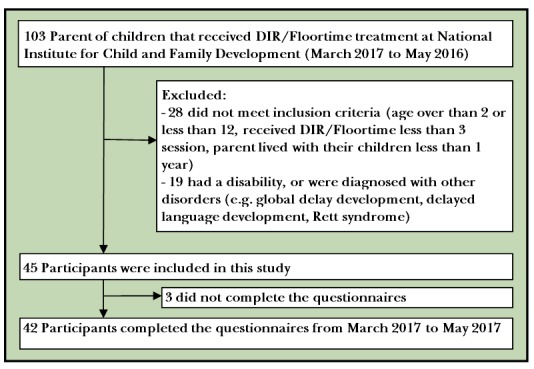

The required sample size calculated using Yamane’s formula21 (with an error of 10% and with 95% confidence coefficient) was 37 participants. Eight participants (20% of calculated sample size) were added to compensate for drop-out or missing data. The total number of participants required for this study were therefore 45. The data were collected from 15 March 2017 to 15 May 2017, in which 103 parents of children that received DIR/Floortime treatment came to NICFD during that time. Twenty-eight of them were excluded due to not meeting inclusion criteria (eg, were not aged between 2 years and 12 years, received less than three sessions of DIR/Floortime or parent lived with their child less than 1 year), 19 of them had a disability or were diagnosed with other disorders (eg, global delayed development, delayed language development and Rett syndrome) and 11 declined to participate (figure 1). Participants were informed about the data collecting method, and informed consent was obtained. This study received ethical approval from the Mahidol University Central Institutional review board (certification number MU-CIRB 2017/002.0501).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study. NICFD, National Institute for Child and Family Development.

Therapists

Therapists needed to have more than 5 years’ experience with DIR/Floortime at NICFD. Moreover, they had to go through DIR/Floortime and have the required skills and knowledge about DIR/Floortime.

Research instruments

Part 1: parental factors were collected using a questionnaire that we developed. First, the general information questionnaire consisted of parental gender, age, occupation, marital status, primary caregivers (father/mother, not father/mother), family size (single/extended family), number of children in family, level of education and monthly income. Second, knowledge of DIR/Floortime techniques questionnaire that contained eight questions related to the fundamental knowledge of DIR/Floortime usage were used in order to evaluate the knowledge of DIR/Floortime principles. The questionnaire was written in multiple-choice form with 1 point for the correct answer to each question. Despite this questionnaire being developed by researchers, psychologists and paediatricians who were experts in DIR/Floortime techniques, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was equal to 0.525. Third, we administered the attitude towards ASD (four items) and DIR/Floortime techniques (five items) questionnaire, which were developed by our team. There are four options (strongly agree, agree, disagree and strongly disagree) for each item. Sum score were divided into two groups: excellent (>28 points) and fair (≤28 points) attitude towards ASD and DIR/Floortime techniques. The reliability and content validity of the questionnaire were excellent (Item-Objective Congruence by three experts was 0.96, and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.832, respectively).

To measure the severity of depression in parents, we used the Patient Health Questionaire-9 Thai version. This questionnaire consisted of nine questions with four options (not at all, several days, more than half the days and nearly every day). Sum score was divided into five groups: minimal depression (0–4 points), mild depression (5–9 points), moderate depression (10–14 points), moderate severe depression (15–19 points) and severe depression (>20 points). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient equaled 0.79 with the validity consistently with the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression equal to 0.56 (sensitivity=53%, specificity=98%).22

Part 2 included child factors such as gender, age and severity of diagnosis. Severity of the diagnosis was collected using the Clinical Global Impressions-Severity (CGI-S) (Cohen’s kappa by two independent assessors=0.69). In addition, the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS), which is a therapist rating questionnaire, was also used to evaluate the severity of ASD. It contains 15 questions with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient equal to 0.7923 (the Cronbach’s alpha was equal to 0.908 in this study).

Part 3 was provider and service factors collected by using questionnaires that we developed. First, regarding relationship with their therapists, we ask the participants, ‘How is your relationship between you and the DIR/Floortime therapists?’. There are three options (excellent, fair and not good) for this question. Finally, duration of the treatment was asked using the question ‘How long ago did you start using DIR/Floortime with your children?’. We left blank spaces to answer this question in years and months format.

Finally, in part 4, parent engagement was evaluated by using an evaluation form that we developed. First, the therapist evaluated the quality of parent engagement in DIR/Floortime, which included three components: (1) coaching, which is the parent’s attention to advice given by therapist while they are interacting with the child. We asked them with the question, ‘How much attention does your parent pay to your advice?’ to evaluate this component. (2) Modelling, which is the parent’s attention while observing the therapist using DIR/Floortime techniques with children. We ask them the question, ‘ How much attention does your parent pay to you while you are using DIR/Floortime with their children?’. There are five options for both questions (not interested=1, sometime=2, often=3, always=4, always and ask questions when they are in doubt=5). (3) Reflection, which is the parent’s reflection on what they have learnt in each therapy session. We assess this component with the question, ‘How much do parents reflect what they learn from the sessions?’. There are five options for this question (do not reflect=1, poorly reflect=2, fairly reflect=3, reflect well=4 and perfectly reflect=5). Sum scores were divided into two groups: high (>10 points) and low (≤10 points) to measure quality of parent engagement in DIR/Floortime. Inter-rater reliability for the whole questionnaire and reflection components was excellent (Cohen’s kappa=1.00) but moderate for coaching and modelling components (Cohen’s kappa=0.412, 0.444, respectively).

Second, we evaluated how much parents use the DIR/Floortime technique at home with their child by having them fill out answers in a blank space. The questionnaire included questions about time spent on using DIR/Floortime techniques per day (How much do you spent on using DIR/Floortime techniques with your child per day?), practising daily life skills (How much do you spend on practicing daily life skills per day?) and structured activities at home per day (How much do you spend on practicing structured activities at home per day?).

Part 5: for improvement of child’s development, Functional Emotional Developmental Level (FEDL), which is clinical ratings evaluation by therapist developed by Solomon and colleagues, was used.24 The therapist assesses the child’s holistic development and emotional and social development, which had six steps according to DIR/Floortime theory as the following: (1) calm regulation and attentiveness; (2) relationship with others; (3) emotional intent; (4) problem-solving communication; (5) emotional ideas; and (6) logic. Each step was divided into 0.5 point. To find the FEDL difference, we subtract the sum score of the FEDL at last session with the sum score of the FEDL when the child started the therapy (as recorded in the medical records). We also used the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement (CGI-I) scale to assess improvement of child’s development with seven options (1=very much improved, 2=much improved, 3=minimally improved, 4=no change, 5=minimally worse, 6=much worse and 7=very much worse), the inter-rater reliability of the CGI-I was almost perfect (Cohen’s kappa of 1.00). We found that the FEDL difference was significantly correlated with the CGI-I score (r=−0.494, p=0.001).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done with SPSS V.22.0. Descriptive statistics were used to report frequency, percentage, mean and SD for demographic data, parents, child, and provider and service factors, together with parent engagement and improvement of child development. χ2 test was used to report association between parent, child, and provider and service factors and parent engagement (likelihood ratio was used to test association in low-frequency variants rather than Fisher’s exact test, due to recent studies that found comparable statistical result.25 26 t-Test was used for comparing the average score between parent engagement and improvement of child development.

Results

Demographic data

The group consisted of 42 participants of whom 31 were female (73.8%). The mean(SD) age of participants was 40.93 (7.73) years old. Thirty-one of them had an occupation (73.8%) and 38 of them were living with their spouses (90.5%). Thirty-five of the participants were father/mother (83.3%), and 26 of them were single family (61.9%). As for the education level, there were 27 people who obtained a Bachelor’s degree or lower (64.3%). For monthly income, there were 22 of the participants with a monthly income more than 50 001 baht (52.4%). As for children, there were 42 participants of which 33 were boys (78.6%) with a mean (SD) age of 6.07 (0.45) years old and 26 of them were still in early childhood (61.9%). Furthermore, 10 of them were using psychotropic medication (23.8%) (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data

| N | % | Mean (SD) | Min–max | |

| Parent | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 11 | 26.2 | ||

| Female | 31 | 73.8 | ||

| Age | ||||

| Early adult (20–40 years) | 18 | 42.9 |

40.93

(1.19) |

25 –64 |

| Middle adult (41–64 years) | 24 | 57.1 | ||

| Occupation | ||||

| Employed | 31 | 73.8 | ||

| Unemployed (housewife) | 11 | 26.2 | ||

| Status | ||||

| Living with spouses | 38 | 90.5 | ||

| Widow/divorce/separated | 4 | 9.5 | ||

| Primary caregivers | ||||

| Father/mother | 35 | 83.3 | ||

| Not father or mother | 7 | 16.7 | ||

| Family size | ||||

| Single family | 26 | 61.9 | ||

| Extended family | 16 | 38.1 | ||

| Education level | ||||

| Bachelor’s degree or lower | 27 | 64.3 | ||

| Higher than Bachelor’s degree | 15 | 35.7 | ||

| Income | ||||

| Less than or equal to 50 000 baht | 20 | 47.6 | ||

| More than 50 000 baht | 22 | 52.4 | ||

| Child | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 33 | 78.6 | ||

| Female | 9 | 21.4 | ||

| Age | ||||

| Early childhood (2–6 years) | 26 | 61.9 |

6.07

(0.45) |

2– 12 |

| Middle childhood (7–12 years) | 16 | 38.1 | ||

| Psychotropic medication use | ||||

| Yes | 10 | 23.8 | ||

| No | 32 | 76.2 | ||

Parent, child, and provider and service factors

Parents had a mean (SD) score of 6.88 (0.20) points for the knowledge of DIR/Floortime, while 17 (40.5%) and 18 of parents (42.9%) had minimal and mild depression, respectively. As for the score reflecting attitude towards ASD and DIR/Floortime techniques, the mean (SD) total score was 31.71 (0.54) points (14.02 (0.22) and 17.69 (0.44) points for the average of the attitude towards ASD and DIR/Floortime techniques, respectively).

As for children, the mean (SD) age that they started the treatment was 3.54 (0.26) years old. The CGI-S scores showed that 17 of the children (40.5%) were equally in moderately and markedly level of severity. Once the severity was assessed by CARS, it was found that there were 32 (76.2%) children who were severe.

As for providers, there were 95.2% of the parents that had an excellent relationship with the therapists. The mean (SD) duration of treatment was 30.62 (4.31) months (table 2).

Table 2.

Parent, child, and provider and service factors

| N | % | Mean (SD) | Min–max | |

| Parent | ||||

| Knowledge of DIR/Floortime | 6.88 (0.20) | 4–8 | ||

| Parent depression level | ||||

| Minimal depression | 17 | 40.5 | ||

| Mild depression | 18 | 42.9 | ||

| Moderate depression | 5 | 11.9 | ||

| Moderate severe depression | 2 | 4.8 | ||

| Severe depression | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Attitude | ||||

| Attitude towards ASD | 14.02 (0.22) | 12-16 | ||

| Attitude towards DIR/Floortime | 17.69 (0.44) | 5-20 | ||

| Attitude towards ASD and DIR/Floortime | 31.71 (0.54) | 19-36 | ||

| Child | ||||

| Average age at the beginning of treatment | 3.54 (0.26) | |||

| The severity of the diagnosis using CGI-S | ||||

| Normal (1) | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Borderline (2) | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Mildly (3) | 4 | 9.5 | ||

| Moderately (4) | 17 | 40.5 | ||

| Markedly (5) | 17 | 40.5 | ||

| Severely (6) | 4 | 9.5 | ||

| Extremely (7) | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| The severity of the diagnosis using CARS | ||||

| Mild to moderate | 10 | 23.8 | ||

| Severe | 32 | 76.2 | ||

| Provider and service | ||||

| Relationship between parent and therapists | ||||

| Excellent | 40 | 95.2 | ||

| Poor | 2 | 4.8 | ||

| Time period since the beginning of the treatment | 30.62 (4.31) | 1–96 | ||

ASD, autism spectrum disorder; CARS, Childhood Autism Rating Scale; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions-Severity; DIR, Developmental, Individual-differences, Relationship-based model.

Parent engagement in DIR/Floortime

Seventeen parents (40.5%) had a high-quality engagement in DIR/Floortime. The mean (SD) time parents spent on using DIR/Floortime techniques, practiing daily life skills and structured activities with their children at home were 140.95 (20.65), 104.76 (12.73) and 82.26 (11.08) minutes/day, respectively (table 3).

Table 3.

Parent engagement in DIR/Floortime

| N | % | Mean (SD) (min/day) | Min–max (min/day) | |

| Parent engagement | ||||

| Quality of parent engagement | ||||

| High | 17 | 40.5 | ||

| Low | 25 | 59.5 | ||

| Homework (min) times spent on using DIR/Floortime | ||||

| Less than or equal to 2 hours | 28 | 66.7 | 140.95 (20.65) | 0-720 |

| More than 2 hours | 14 | 33.3 | ||

| Times spent on practice of daily life skills (per day) | ||||

| Less than or equal to 1 hours | 25 | 59.5 | 104.76 (12.73) | 5-360 |

| More than 1 hours | 17 | 40.5 | ||

| Times of structured activities at home (per day) | ||||

| Less than or equal to 1 hours | 30 | 71.4 | 82.26 (11.08) | 5–360 |

| More than 1 hours | 12 | 28.6 | ||

DIR, Developmental, Individual-differences, Relationship-based model.

Improvement in child development

Most children had the level of child development, as assessed by FEDL, equal to 1.0 (35.7%) on starting DIR/Floortime techniques and equal to 3.0 (21.4%) at the last visit. The mean (SD) FEDL score difference was equal to 2.25 (0.16). For the CGI-I, it was showed that 21 children were much improved (50.0%) and 19 children were minimally improved (45.2%).

Correlation between parents, children, and provider and service factors with parent engagement in DIR/Floortime

Parents who lived with their spouses tended to help children practice daily life skills more than 1 hour/day, which was more than parents who were widows/widowers, divorced or separated (χ2=4.43, p=0.035). Parents who earned less than or equal to 50 000 baht/month tended to spend time on using DIR/Floortime techniques with their children more than 2 hours/day when compared with parents who earned more monthly (χ2=13.1, p<0.001). In addition, parents who had higher scores of knowledge about DIR/Floortime (>6 points) tended to have more parent engagement quality in DIR/Floortime than those who had lower scores (≤6 points) (χ2=4.06, p=0.044). Participants with an ‘excellent’ attitude (as rated by the scale) towards the diagnosis and DIR/Floortime techniques tended to practice daily life skills with their children more than 1 hour per day as compared with those whose attitude was rated as ‘fair’ (χ2=3.65, p=0.056).

It was found that parents of children with a high severity level on the spectrum tended to spend more than 1 hour/day practicing daily skills when compared with parents whose children were mild-to-moderate severity level (χ2=5.83, p=0.016).

Additionally, in terms of factors associated with provider and service factors, it was found that parents who practised DIR/Floortime techniques for more than 48 months tended to have a higher quality of parent engagement than parents who practised less than or equal to 48 months (χ2=4.72, p=0.030) (table 4).

Table 4.

Association between parents, children and therapists factors with parent engagement in DIR/Floortime

| Quality of parental engagement | χ2 | P values | Time spenton using DIR/Floortime | χ2 | P values | Time spent on practice daily life skills | χ2 | P values | Times of structured activities | χ2 | P values | |||||

| Low | High | ≤2 hours | >2 hours | ≤1 hour | >1 hour | ≤1 hour | >1 hour | |||||||||

| Parent | ||||||||||||||||

| Status | 0.47 | 0.495* | 3.45 | 0.063* | 4.43† | 0.035* | 0.28 | 0.866* | ||||||||

| Living with spouses | 22 | 16 | 24 | 14 | 21 | 17 | 27 | 11 | ||||||||

| Widow/divorce/Separated | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 1 | ||||||||

| Income | 0.48 | 0.491 | 13.10‡ | <0.001 | 3.34 | 0.067 | 0.04 | 0.845 | ||||||||

| ≤50 000 baht | 13 | 7 | 8 | 12 | 9 | 11 | 14 | 6 | ||||||||

| >50 000 baht | 12 | 10 | 20 | 2 | 16 | 6 | 16 | 6 | ||||||||

| Knowledge of DIR/Floortime | 4.06† | 0.044 | 0.00 | 1.000 | 0.37 | 0.543 | 0.26 | 0.613 | ||||||||

| ≤6 points | 12 | 3 | 10 | 5 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 5 | ||||||||

| >6 points | 13 | 14 | 18 | 9 | 17 | 10 | 20 | 7 | ||||||||

| Parent depression level | 0.02 | 0.888* | 0.09 | 0.767* | 2.69 | 0.101* | 0.79 | 0.374* | ||||||||

| Minimal to mild | 21 | 14 | 23 | 12 | 19 | 16 | 26 | 9 | ||||||||

| Moderate to moderate severe | 4 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 3 | ||||||||

| Attitude | 0.04 | 0.848* | 2.21 | 0.138* | 3.65 | 0.056* | 0.06 | 0.802* | ||||||||

| Excellent | 20 | 14 | 21 | 13 | 18 | 16 | 24 | 10 | ||||||||

| Good | 5 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 2 | ||||||||

| Child | ||||||||||||||||

| Average age (beginning of treatment) | 0.32 | 0.569 | 0.19 | 0.662 | 1.74 | 0.187 | 0.24 | 0.625 | ||||||||

| ≤ 3 years | 11 | 9 | 14 | 6 | 14 | 6 | 15 | 5 | ||||||||

| >3 years | 14 | 8 | 14 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 15 | 7 | ||||||||

| Severity | 0.00 | 0.972* | 1.12 | 0.290* | 5.83† | 0.016* | 0.01 | 0.909* | ||||||||

| Mild to moderate | 6 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 7 | 3 | ||||||||

| Severe | 19 | 13 | 20 | 12 | 16 | 16 | 23 | 9 | ||||||||

| Provider and service | ||||||||||||||||

| Relationship | 0.08 | 0.780* | 1.67 | 0.196* | 0.78 | 0.780* | 1.39 | 0.239* | ||||||||

| Excellent | 24 | 16 | 26 | 14 | 24 | 16 | 28 | 12 | ||||||||

| Poor | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | ||||||||

| Time period (beginning of treatment) | 4.72† | 0.030* | 0.26 | 0.612* | 0.49 | 0.485* | 0.81 | 0.370* | ||||||||

| ≤48 months | 22 | 10 | 22 | 10 | 20 | 12 | 24 | 8 | ||||||||

| >48 months | 3 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 4 | ||||||||

*Likelihood ratio test.

†Correlation is significant at the 0.05 (two tailed).

‡Correlation is significant at the 0.01 (two tailed).

DIR; Developmental, Individual-differences, Relationship-based model.

Association between improvement of child developmental level and parent engagement in DIR/Floortime

Children whose parents spent more than 1 hour/day on practising daily life skills had a higher average CGI-I score than those whose parents spent less hours (t=−2.03, p=0.049). Additionally, children of parents with high quality of parental engagement in DIR/Floortime tended to have a higher FEDL difference score than the ones whose parents had lower quality parental engagement (t=−2.00, p=0.053) (table 5).

Table 5.

Association between improvement of child developmental level and parent engagement in DIR/Floortime

| Developmental improvement | CGI-I | |||||||

| N | Mean (SD) | t | P values | N | Mean (SD) | t | P values | |

| Quality of parent engagement | ||||||||

| Low | 25 | 2.00 (0.20) | −2.00 | 0.053 | 25 | 2.56 (0.12) | 0.16 | 0.872 |

| High | 17 | 2.62 (0.23) | 17 | 2.53 (0.15) | ||||

| Times spent on using DIR/Floortime (per day) | ||||||||

| ≤2 hours | 28 | 2.29 (0.18) | 0.32 | 0.753 | 28 | 2.57 (0.11) | 0.36 | 0.718 |

| >2 hours | 14 | 2.18 (0.31) | 14 | 2.5 (0.17) | ||||

| Times spent on practice of daily life skills (per day) | ||||||||

| ≤1 hours | 25 | 2.46 (0.20) | 1.65 | 0.106 | 25 | 2.40 (0.10) | −2.03 | 0.049* |

| >1 hours | 17 | 1.94 (0.25) | 17 | 2.76 (0.16) | ||||

| Times of structured activities at home (per day) | ||||||||

| ≤1 hours | 30 | 2.20 (0.20) | −0.50 | 0.621 | 30 | 2.50 (0.10) | −0.82 | 0.417 |

| >1 hours | 12 | 2.38 (0.25) | 12 | 2.67 (0.19) | ||||

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 (two tailed).

†Correlation is significant at the 0.01 (two tailed).

DIR; Developmental, Individual-differences, Relationship-based model.

Discussion

Main findings

This current research found that most parents had good knowledge in DIR/Floortime techniques and a good attitude towards ASD and DIR/Floortime techniques. Most parents adequately spent their time using DIR/Floortime at home according to the principle of DIR/Floortime techniques (20–30 min/time and 6–10 times/day).1 However, the sample group in this study were parents who continuously participated in DIR/Floortime techniques training but did not include the samples who irregularly visited or stopped.

We found that parents who lived with spouses were more likely to be practising daily life skills with their child. This result is supported by several studies that found that parents’ marital status is positively correlated with parental engagement in various interventions.19 27 Parents who were married had more skills and experiences than parents who were still single, and they already had less problems during training.19 Moreover, parents who lived with their spouses could help each other in taking care of their children. Studies also found that parents with lower income spent more time in practising DIR/Floortime techniques with their children that was opposed to the results of previous studies, which found that parents with higher income had better parental engagement.19 28 29 Parents who earned less might not be working or have resigned from their jobs or were working at home in order to take care of and apply DIR/Floortime techniques with their children. However, our participants were mostly employed. Furthermore, a study showed that knowledge in using DIR/Floortime techniques correlated with high-quality parental engagement. The parents who understood the techniques well felt that they were capable of using the techniques.30 We also found that parents who had a good attitude towards ASD and DIR/Floortime techniques were more likely to practice daily life skills interventions with their children. This result is supported by research that found that good attitude towards ASD and confidence in the treatment were positively correlated with good parental engagement.12 If one believed that ASD symptoms could be improved and trusted in the application of these techniques, they would be more likely to spend time using them with their children.

As for factors associated with children, we found that parents who lived with children with higher severity of ASD were more likely to practice daily skills with their children.14 There is a study showing that a factor potentially affecting parent involvement is severity,29 and parents of children who exhibit more behavioural problems (high severity) had more parent engagement.31 Parents might be worried and expect their children to have better development, so they tended to spend more time practising their children’s skills.

For provider and service factors, the results showed that parents who had longer duration of treatment were more likely to have higher quality of parental engagement. Parents who had been practising the techniques for a long time would have a lot of experience and knowledge, so these would reflect in the quality of engagement in therapy.

Furthermore, this current research also found that children of parents who spent more time on practising daily life skills with them were more likely to have a higher CGI-I average score than children of parents who spent less time. Additionally, children of parents with higher quality of parent engagement were more likely to have a higher average score of FEDL difference than children whose parents had lower quality of engagement. These findings emphasise the importance of having good parental engagement, which may further improve child development. Parents with high quality of parental engagement may apply more appropriate techniques with their children both at home and during the therapy sessions that might improve their children’s development. These results correlate with a study that found that parent engagement and the continuity of technique usage were major factors for increasing child developmental level.32 According to Kasari and colleagues,33 high parental engagement has a positive effect on children’s joint engagement and decreases children’s object-only focused engagement, which were are deficits commonly seen in patients with ASD. Similarly, in Thailand, there was research that followed children with ASD who received DIR/Floortime treatment and found that 54% of these children who regularly received the treatment had improved their emotional and social development.34 These results indicated that the main factors that help improve child development were parent engagement in using DIR/Floortime techniques, especially using such techniques in daily life and the quality of the engagement. However, our study did not find a correlation between time that parents spent using DIR/Floortime techniques with their children at home and child development. Further study should include specific skills such as communication skills, social skills, behavioural problems and joint engagement, which might also be correlated with parental engagement.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, even though our number of participants in this study exceed the calculated sample size, further studies should include a larger number of participants. Moreover, we did not include the samples who irregularly received or stopped the treatment. Therefore, there might be a selection bias in our participants. Second, despite our participants being diagnosed by paediatricians and child and adolescence psychiatrists according to DSM-IV-TR ASD diagnostic criteria, we did not use a gold standard instrument to diagnose, for example, the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule. Third, we did not use Fisher’s exact test, which was usually used in other studies for analysis of small sizes. More recent studies found comparable statistical results between using likelihood ration and Fisher’s exact test.25 26 However, after using Fisher’s exact test, we still found significant association between severity and time spent practising daily life skills (p=0.031). Fourth, even this research examined various factors associated with parents, children and therapists, there may be some important factors that are not included in this study such as the expectations towards treatment and the motivation in receiving the treatment.35 Finally, although our study showed a correlation between parent engagement and child development, we did not include some specific skills related to ASD (eg, communication skills, social skills, behaviour problems and emotional problems) in our assessment. Therefore, these factors should be included in future studies.

Implication

Many factors such as parents marital status, income, knowledge of principles, attitude towards ASD and techniques, severity of ASD and duration of treatment had a positive correlation with parental engagement in DIR/Floortime. Therefore, an individual that uses DIR/Floortime techniques needs to consider these factors and provide appropriate assistance for each patient in order to decrease the challenges and increase supporting factors to improve parental engagement.

gpsych-2018-000009supp001.docx (5.9KB, docx)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the director and therapists from the National Institute for Child and Family Development for supporting and allowing us to collect data, and we would also like to thank all the participants for their cooperation in answering the questionnaire.

Biography

Nattakit Praphatthanakunwong obtained a bachelor’s degree from Srinakharinwirot University in 2015, and currently is a graduate student in the Master of Science Program in Child, Adolescent, and Family Psychology (Joint curriculum program by Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital and National Institute for Child and Family Development, Mahidol University). His research interests include ASD and children with special needs.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors conceived and designed the study and acquired the data. NP analysed and interpreted the data. NP and KK drafted the manuscript. The manuscript was critically revised by KK. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study received ethical approval from the Mahidol University Central Institutional Review Board (certification number MU-CIRB 2017/002.0501) on 24 February 2017.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Pajareya K. A guide to developing autistic children (DIR/Floortime). 2553 Bangkok: Pimsri, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rahman A, Divan G, Hamdani SU, et al. Effectiveness of the parent-mediated intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder in south Asia in India and Pakistan (PASS): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3:128–36. 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00388-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pajareya K, Nopmaneejumruslers K. A pilot randomized controlled trial of DIR/Floortime parent training intervention for pre-school children with autistic spectrum disorders. Autism 2011;15:563–77. 10.1177/1362361310386502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Khunkaew Y. Autistic: knowledge for development. Human resources development journal 2018, 2: 144. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pornnoppadol C. Autism and the pervasive developmental disorders : Piyasilp V, Katemarn P, Textbook of child and adolescent psychiatry. Nonthaburi: beyond enterprise, 2018: 141–66. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Humphrey D. U.S.-Thailand prediction of regressive autism and its prevention cooperation. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual 2008;1. [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Institute for Child and Family Development Mahidol university. A guide to developing delay and special children in holistic way (DIR/Floortime) happiness version. 2558, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Buschbacher P, Fox L, Clarke S. Recapturing desired family routines: a parentprofessional behavioral collaboration. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 2004;29:25–39. 10.2511/rpsd.29.1.25 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burrell TL, Borrego, J. Parents' involvement in ASD treatment: what is their role? Cogn Behav Pract 2012;19:423–32. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.04.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brookman-Frazee L, Koegel RL. Using parent/clinician partnerships in parent education programs for children with autism. J Posit Behav Interv 2004;6:195–213. 10.1177/10983007040060040201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moroz AK. Exploring the factors related to parent involvement in the interventions of their children with autism. California, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hines M, Balandin S, Togher L. Buried by autism: older parents' perceptions of autism. Autism 2012;16:15–26. 10.1177/1362361311416678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rodger S, Keen D, Braithwaite M, et al. Mothers’ Satisfaction with a Home Based Early Intervention Programme for Children with ASD. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 2008;21:174–82. 10.1111/j.1468-3148.2007.00393.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Holdsworth E, Bowen E, Brown S, et al. Client engagement in psychotherapeutic treatment and associations with client characteristics, therapist characteristics, and treatment factors. Clin Psychol Rev 2014;34:428–50. 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Allen JG, Newsom GE, Gabbard GO, et al. Scales to assess the therapeutic alliance from a psychoanalytic perspective. Bull Menninger Clin 1984;48:383–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. VanDeMark NR, Burrell NR, Lamendola WF, et al. An exploratory study of engagement in a technology-supported substance abuse intervention. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 2010;5:10–23. 10.1186/1747-597X-5-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boardman T, Catley D, Grobe JE, et al. Using motivational interviewing with smokers: do therapist behaviors relate to engagement and therapeutic alliance? J Subst Abuse Treat 2006;31:329–39. 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moyers TB, Miller WR, Hendrickson SML. How does motivational interviewing work? Therapist interpersonal skill predicts client involvement within motivational interviewing sessions. J Consult Clin Psychol 2005;73:590–8. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Clark DB, Baker BL. Predicting outcome in parent training. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983;51:309–11. 10.1037/0022-006X.51.2.309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th edn Washington, DC: Text Revision American Psychiatric Association, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yamane T. Statistics: an introductory analysis. Harper & Row, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lotrakul M, Sumrithe S, Saipanish R. Reliability and validity of the Thai version of the PHQ-9. BMC Psychiatry 2008;8:46 10.1186/1471-244X-8-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Russell PS, Daniel A, Russell S, et al. Diagnostic accuracy, reliability and validity of Childhood Autism Rating Scale in India. World J Pediatr 2010;6:141–7. 10.1007/s12519-010-0029-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Solomon R, Necheles J, Ferch C, et al. Pilot study of a parent training program for young children with autism: the PLAY Project Home Consultation program. Autism 2007;11:205–24. 10.1177/1362361307076842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kroonenberg PM, Verbeek A. The tale of cochran's rule: my contingency table has so many expected values smaller than 5, what am i to do? The American Statistician 2017:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Choi L, Blume JD, Dupont WD. Elucidating the foundations of statistical inference with 2 x 2 tables. PLoS One 2015;10:e0121263 10.1371/journal.pone.0121263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gopalan G, Goldstein L, Klingenstein K, et al. Engaging families into child mental health treatment: updates and special considerations. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010;19:182–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bennett A. Parental involvement in early intervention programs for children with autism. master of social work clinical research papers, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Benson P, Karlof KL, Siperstein GN. Maternal involvement in the education of young children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism 2008;12:47–63. 10.1177/1362361307085269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Solomon M, Ono M, Timmer S, et al. The effectiveness of parent-child interaction therapy for families of children on the autism spectrum. J Autism Dev Disord 2008;38:1767–76. 10.1007/s10803-008-0567-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Garbacz SA, McIntyre LL, Santiago RT. Family involvement and parent-teacher relationships for students with autism spectrum disorders. Sch Psychol Q 2016;31:478–90. 10.1037/spq0000157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lovaas OI, Koegel R, Simmons JQ, et al. Some generalization and follow-up measures on autistic children in behavior therapy. J Appl Behav Anal 1973;6:131–65. 10.1901/jaba.1973.6-131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kasari C, Gulsrud AC, Wong C, et al. Randomized controlled caregiver mediated joint engagement intervention for toddlers with autism. J Autism Dev Disord 2010;40:1045–56. 10.1007/s10803-010-0955-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nopmaneejumruslers K, Maisook P. Sumalrot T. A follow-up study of autistic children that using DIR/Floortime in treatment. Thai journal of pediatrics;55:284–92. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hastings RP, Johnson E. Stress in UK families conducting intensive home-based behavioral intervention for their young child with autism. J Autism Dev Disord 2001;31:327–36. 10.1023/A:1010799320795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

gpsych-2018-000009supp001.docx (5.9KB, docx)