Abstract

The mermaid syndrome (sirenomelia) is an extremely rare anomaly, an incidence of 1 in 100,000 births, in which a newborn born with legs joined together featuring a mermaid-like appearance (head and trunk like humans and tail like fish), and in most cases die shortly after birth. Gastrointestinal and urogenital anomalies and single umbilical artery are clinical outcome of this syndrome. There are two important hypotheses for pathogenesis of mermaid syndrome: vitelline artery steal hypothesis and defective blastogenesis hypothesis. The cause of the mermaid syndrome is unknown, but there are some possible factors such as age younger than 20 years and older than 40 years in mother and exposure of fetus to teratogenics. Here, we introduced 19-year-old mother's first neonate with mermaid syndrome. The mother had gestational diabetes mellitus and neonate was born with single lower limb, ambiguous genitalia, and thumb anomalies, and 4 days after birth, the neonate died due to multiple anomalies and imperforated anus.

Keywords: mermaid syndrome, sirenomelia, single lower limb, single umbilical artery, thumb deformity

Mermaid syndrome (sirenomelia) is a very rare congenital anomaly that is born with an evolutionary defect in the caudal region with varying degrees of leg adhesion, causing a complete absence of the lower limb with a very similar appearance to the perianal. The earliest evidence for the mermaid syndrome was traced back to the 16th century. 1 2

The prevalence of this anomaly is 1 in 100,000 births. So far 300 patients with this rare anomaly have been reported in the world. The incidence of male to female is 3 to 1. 3 The incidence in monozygote twins were reported 150 to 200 times; 200 times more likely to be seen in a newborn with diabetes mothers; 15% of mothers had gestational diabetes mellitus during pregnancy. 4 5

Case Report

A term neonate with ambiguous genitalia and single lower limb was born to a 19-year-old mother with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus. The neonate was the first child of the family and parents did not have a familial relationship. The mother did not have any health care and medical treatment at the time of pregnancy. The neonate's birth weight was 3,500 g.

Video 1 Video showing the case report from different positions. Online content including video sequences viewable at: www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/html/10.1055/s-0038-1669943 .

In the first examinations, the head, face, and neck were normal. In the upper limb, the thumb was connected with a small connector to left hand. The auscultation of heart and lung were normal. There was no problem with the chest wall. The abdomen was clearly turgid, but the liver and the lungs were not big at the touch ( Fig. 1 ).

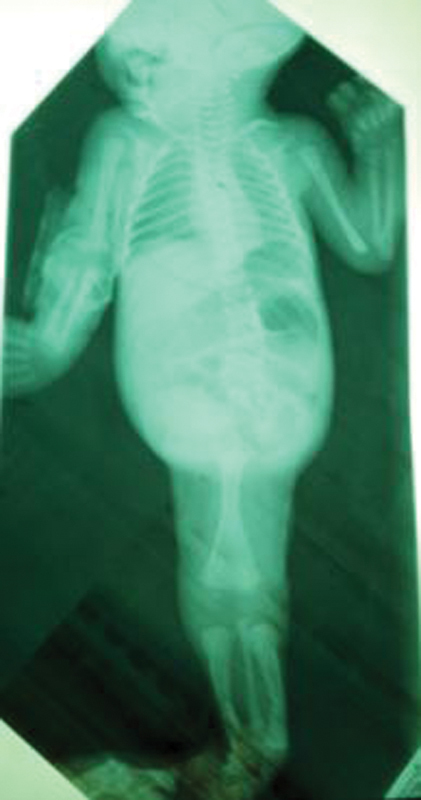

Fig. 1.

Radiography of a neonate with sirenomelia.

The umbilical cord had an artery and a vein. At the end of the abdomen, there was a deviant limb in front facing at the rear, with two heels, followed by two thumbs and six fingers, and with a relatively tall and nail-like arrangement ( Fig. 2 ). There was a dent in the back of the neonate at the end of the spine of the lumbar region. Sacral bone was not touchable, and there was no pelvic bone on the left. At the junction of the spine, there was an isolated single limb of the hole in the closed face and ∼3 cm lower than the anterior cavity of the ellipsoidal shape that was seen locally. The bottom of the cavity was duct. Urinary tract was not seen. However, urinary excretion dropped out of the occipital cavity ( Fig. 3 ). In examining the echocardiogram, the heart and heart vessels were normal.

Fig. 2.

Anterior view of a neonate with sirenomelia.

Fig. 3.

Posterior view of a neonate with sirenomelia.

In sonography, the liver, the bile ducts, and prostatic fluid were reported to be normal. The left kidney did not exist. The right kidney was larger than normal and the bladder was small and abnormal. Internal genital organs including testicular gonads, ovaries, and veins were not observed. The umbilical artery with a large diameter of the abdominal aortic artery originated, and the rest of the abdominal aortic pathway after the umbilical artery had irregular branches and hypoplastic.

In the entire radiography of the body, there were sacral bone agenesis and pelvic bone agenesis. There were femur bone and two tibia bones and a fibula bone and two heel and toes were seen. During patient hospitalization, the neonate had urinary excretion as a droplet, but no excretion of stool was observed. The neonate developed shortly after birth, abdominal distension, bile vomiting, and oral intolerance. The neonate was fed intravenously during life. Neonate bile vomiting continued with fecal material removal, and after that, the neonate died 4 days after birth with a block of bowel obstruction and generalized peritonitis ( Video 1 ). The parents did not consent to do an autopsy. Chromosome examination was not done.

Discussion

Mermaid syndrome is an extremely rare anomaly that was first reported in 1,542 by Rocheus et al and later by Palfyn et al in 1543. Mermaid means trunk looks like human and rear looks like a fish. 5 6

In 1961, Duhamel classified the mermaid syndrome as type 5 caudal regression syndrome (CRS) for the similarity with CRS anomalies. 7 But nowadays, mermaid is a separate syndrome, and the diagnostic key is the presence of single umbilical artery and renal agenesis, which is a stable clinical syndrome in mermaid, while in the CRS, there is a dysfunction and no deadly kidney anomalies. 8

In 1987, Stocker and Heifetz introduced the theory of vitelline artery steal and reported that all patients with sirenomelia had a large umbilical artery, separated from the upper abdominal artery aorta slightly below the celiac artery, and the branches of other aorta had not evolved. This suggested that due to the lack of blood supply and inadequate nutrition, the growth of the lower part of the body was stopped and led to sacral agenesis, lower limb fusion, imperforated anus, rectal agenesis, internal and external absence of genitalia, and renal agenesis. 9

Although the main factor for mermaid syndrome is unknown, there are two important hypotheses that brings about mermaid syndrome: vitelline artery steal hypothesis and defective blastogenesis hypothesis. According to the theory of vitelline artery steal hypothesis, due to the discoloration of the vitelline artery, the celiac artery is shortly separated from the abdominal aorta, and the remainder of the aortic arteries is either absent in the arterial branch or hypoplastic artery. The vitelline artery reduces the blood flow and feeds the caudal portion of the embryo by diverting blood flow from the embryo to the placenta. This occurrence in the third and fourth weeks of the ejaculation causes disturbances of the caudal region in the fetal. 10 Based on the theory of defective blastogenesis, an impaired blastogenesis, in which the lower body organs have inappropriate angiogenesis lead to insufficient growth and incomplete development of the caudal region. 11 Although genetic defects in humans are still unknown in the mermaid syndrome, two defects in the Cyp26a1 and BMP7 genes in mice result in the birth of a mermaid neonate. The Cyp26a1 gene is responsible for coding the enzyme that breaks down retinoic acid (the metabolite of vitamin A). Retinoic acid temporarily increases the vasculature in the caudal region of the embryo. Disruption of the Cyp26a1 gene and incomplete development of the caudal region of the embryo result in a mermaid syndrome in mice. Bone morphogenic protein7) is an important protein that plays an important role in angiogenesis in vitro. By stimulating endothelial cells of the caudal region, vascular and tissue production leads to normal growth of the lower limbs in the fetus. 12 13 14

Anomalies that are commonly seen with the mermaid syndrome include: cleft palate pulmonary hypoplasia, cardiac defects omphalocele, pentalogy of Cantrell, and meningomyelocele. 2 15

Mermaid syndrome occurs sporadically. Neonates born with mermaid syndrome often have normal karyotype. 16 According to Orioli et al, in 249 cases of mermaid syndrome, there have not been any fact regarding repetition in family. Gestational diabetes mellitus is the only known disease in the mother that is associated with the mermaid syndrome. 17 18 19 Mothers younger than 20 years and older than 40 years are vulnerable. The occurrence of the mermaid syndrome in 12 months has been reported in up to 20% of cases. 20 21 Hyperthermia and amniotic band disruption are the underlying causes of the occurrence of the mermaid syndrome. The exposure to teratogenic factors, such as air pollution, and mother-to-drug contact with cocaine and tobacco and alcohol cigarettes, and radionuclide are also among the causes. Fetal exposure to cadmium, lithium, phenytoin, sodium valproate, carbamazepine, warfarin, methylergonovine, diethylpropion, trimethoprim, and ochratoxin (a type of fungus) are also the causes of the birth of the mermaid syndrome in other articles. 22 23 24 It can be diagnosed in prenatal with sonography in the first trimester of pregnancy with following symptoms: nuchal translucency, fused lower limb, single lower limb, renal agenesis, single umbilical artery, and oligohydramnious. 25

Serbest et al 26 reported a 4-year-old girl with congenital clasped thumb anomaly as a result of the absence of extensor pollicis brevis tendon with treatment such as extensor indicis proprius (EIP) transfer and z-plasty reconstruction to first web space. The deformity related to the absence of tendon in cases of isolated clasped thumb deformity with treatment attempts such as splinting and physical treatment have not been successful, EIP tendon transfer and reconstruction of contracture in first web space with Z-plasty are a simple and yet effective method to obtain functional improvement.

Conclusion

According to the findings of the mermaid syndrome, caudal area hemorrhagia has been identified as a major cause and other factors include gestational diabetes mellitus and fetal exposure to teratogenic substances also has been reported. Blood glucose control in pregnant women and prevention of contact of pregnant mother with teratogenic substances is recommended.

Acknowledgments

We greatly thank the “Lorestan University of Medical Sciences, Khoramabad, Iran.”

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None.

References

- 1.Duesterhoeft S M, Ernst L M, Siebert J R, Kapur R P. Five cases of caudal regression with an aberrant abdominal umbilical artery: further support for a caudal regression-sirenomelia spectrum. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A(24):3175–3184. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garrido-Allepuz C, Haro E, González-Lamuño D, Martínez-Frías M L, Bertocchini F, Ros M A. A clinical and experimental overview of sirenomelia: insight into the mechanisms of congenital limb malformations. Dis Model Mech. 2011;4(03):289–299. doi: 10.1242/dmm.007732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reddy K R, Srinivas S, Kumar S, Reddy S, Prasad H, Irfan G M. Sirenomelia: a rare presentation. J Neonatal Surg. 2012;1(01):7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taori K B, Mitra K, Ghonga N P, Gandhi R O, Mammen T, Sahu J. Sirenomelia sequence (mermaid): report of three cases. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2002;12(03):399. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sikandar R, Munim S. Sirenomelia, the mermaid syndrome: case report and a brief review of literature. J Pak Med Assoc. 2009;59(10):721–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schiesser M, Holzgreve W, Lapaire O et al. Sirenomelia, the mermaid syndrome--detection in the first trimester. Prenat Diagn. 2003;23(06):493–495. doi: 10.1002/pd.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duhamel B. From the mermaid to anal imperforation: the syndrome of caudal regression. Arch Dis Child. 1961;36(186):152–155. doi: 10.1136/adc.36.186.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Das B B, Rajegowda B K, Bainbridge R, Giampietro P F. Caudal regression syndrome versus sirenomelia: a case report. J Perinatol. 2002;22(02):168–170. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stocker J T, Heifetz S A. Sirenomelia. A morphological study of 33 cases and review of the literature. Perspect Pediatr Pathol. 1987;10:7–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevenson R E, Jones K L, Phelan M C et al. Vascular steal: the pathogenetic mechanism producing sirenomelia and associated defects of the viscera and soft tissues. Pediatrics. 1986;78(03):451–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Opitz J M, Zanni G, Reynolds J F, Jr, Gilbert-Barness E. Defects of blastogenesis. Am J Med Genet. 2002;115(04):269–286. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zakin L, Reversade B, Kuroda H, Lyons K M, De Robertis E M. Sirenomelia in Bmp7 and Tsg compound mutant mice: requirement for Bmp signaling in the development of ventral posterior mesoderm. Development. 2005;132(10):2489–2499. doi: 10.1242/dev.01822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ribes V, Fraulob V, Petkovich M, Dollé P. The oxidizing enzyme CYP26a1 tightly regulates the availability of retinoic acid in the gastrulating mouse embryo to ensure proper head development and vasculogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2007;236(03):644–653. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheng N, Xie Z, Wang C et al. Retinoic acid regulates bone morphogenic protein signal duration by promoting the degradation of phosphorylated Smad1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(44):18886–18891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009244107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moosa S, Lambie L A, Krause A. Sirenomelia: four further cases with discussion of associated upper limb defects. Clin Dysmorphol. 2012;21(03):124–130. doi: 10.1097/MCD.0b013e328354e51b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orioli I M, Amar E, Arteaga-Vazquez J et al. Sirenomelia: an epidemiologic study in a large dataset from the International Clearinghouse of Birth Defects Surveillance and Research, and literature review. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2011;157:358–373. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Haggar M, Yahia S, Abdel-Hadi D, Grill F, Al Kaissi A. Sirenomelia (symelia apus) with Potter's syndrome in connection with gestational diabetes mellitus: a case report and literature review. Afr Health Sci. 2010;10(04):395–399. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan B W, Chan K S, Koide T et al. Maternal diabetes increases the risk of caudal regression caused by retinoic acid. Diabetes. 2002;51(09):2811–2816. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.9.2811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taee N, Tarhani F, Safdary A. A case of sirenomelia in newborn of a diabetic mother. Int J Diabetes Metab. 2005;5(01):83–87. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dharmraj M, Gaur S. Sirenomelia: a rare case of foetal congenital anomaly. J Clin Neonatol. 2012;1(04):221–223. doi: 10.4103/2249-4847.106006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chowdhury S, Kundu S, Manna S S, Das A. Both babies with sirenomelia'in twin pregnancy: a case report and review of literature. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2017;4(03):908–910. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alexander P G, Tuan R S. Role of environmental factors in axial skeletal dysmorphogenesis. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2010;90(02):118–132. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tica O S, Tica A A, Brailoiu C G, Cernea N, Tica V I. Sirenomelia after phenobarbital and carbamazepine therapy in pregnancy. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2013;97(06):425–428. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barański B. Effect of exposure of pregnant rats to cadmium on prenatal and postnatal development of the young. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol. 1984;29(03):253–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akbayir O, Gungorduk K, Sudolmus S, Gulkilik A, Ark C. First trimester diagnosis of sirenomelia: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278(06):589–592. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0619-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Serbest S, Tosun H B, Tiftikci U, Gumustas S A, Uludag A. Congenital clasped thumb that is forgetten a syndrome in clinical practice: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94(38):e1630. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]