Abstract

We report a case of disseminated cryptococcosis in a 42-year old immunocompetent female. Prior to admission at Bugando Medical Center, the patient was attended at three hospitals for hypertension and clinically diagnosed malaria. Following diagnosis of disseminated Cryptococcus at our center, she was successfully treated with fluconazole but remained with visual loss. Blood cultures should be considered in the management of any adult presenting with fever to enable early detection of the least expected differentials like in this case.

Keywords: Disseminated cryptococcosis, C. gattii, Meningism, Cryptococcus deuterogattii, HIV negative

1. Introduction

Cryptococcal meningitis (CM) is among the common AIDS-defining illnesses, and the leading cause of AIDS-related death among HIV-infected patients admitted at Bugando Medical Center (BMC) with mortality of up to 67% [1]. In contrast to C. neoformans which is prevalent worldwide among HIV-infected patients [2], C. gattii was recently identified as a species found commonly in tropical regions infecting immunocompetent people presenting with neurological and pulmonary cryptococcoma [3]. Cases of disseminated cryptococcosis in immunocompetent individuals have rarely been reported in Sub-Saharan Africa partly due to limited diagnostic facilities and low index of suspicion of the attending clinicians, and this could be a result of overlap of signs and symptoms with other diseases [4], [5]. We present a disseminated cryptococcosis in a HIV-negative woman, a newly diagnosed patient with hypertension who presented with right-sided hemiparesis, fever and signs of meningism. This case stresses the importance of high index of suspicion and extensive work-up in immunocompetent patients presenting with meningism and fever in a resource-limited setting.

2. Case

In April 2017, a 42-year-old woman, presented to the Bugando Medical Center (BMC) as a self-referred patient from home (Mahina, Mwanza) following persistence of headache for one month, fever for two weeks and right-sided weakness for one week. The headache started gradually and progressively became more severe with time. The headache was more severe on the frontal region, throbbing in nature, associated with blurred vision and persistent fevers. She reported to have episodes of nausea and vomiting. The right-sided body weakness started gradually one week prior to BMC admission but the patient could still walk with minimal support. On the course of these symptoms, the patient received care at three hospitals in Mwanza city where she was diagnosed to have hypertension and symptomatic malaria and kept on losartan H. 62.5 mg daily, antimalarials and antibiotics of which she could not recall the name. She denied any history of cough, convulsions, loss of consciousness, head trauma, diabetes mellitus, and steroid/chemotherapy use. On examination, she had fever of 38.1 °C, blood pressure of 180/100 mmHg, positive Kerning's and Brudzinski's signs, was photophobic with pupils that were consensually reacting to light, decreased visual acuity bilaterally, and showed decreased deep reflexes with power grade of 4/5 on right arm and leg. The patient was also found to have a firm, non-tender and non-pulsating nodule (9 ×6 mm) on the right nostril (Fig. 1). Respiratory, abdominal and fundoscopic examination were uneventful.

Fig. 1.

Firm, non-tender and non-pulsating nodule on the right nostril.

Based on examination findings, the patient was clinically diagnosed to have an ischemic stroke with right-sided hemiparesis due to hypertension with a differential diagnosis of bacterial meningitis. She was started on high dose ceftriaxone i.e. 2 g i.v. 12 hourly and ampicillin 2 g i.v. 6 hourly as the empirical management of bacterial meningitis.

A complete blood count revealed white blood cell count, granulocytes, lymphocytes, platelet count and hemoglobin to be 7.0 × 109U/L, 70%, 23.8%, 373 × 109 U/L and 10 g/dL, respectively. HIV testing according to Tanzania HIV Rapid Test Algorithm of 2015 was negative. The CD4 and CD8 cell counts were 519 and 299 cells/µL, respectively. Renal and liver function tests were all within a normal range. Moreover, a chest X-ray was also normal.

On day 3, CT imaging was requested to rule out space occupying lesions, and the findings showed multifocal hypodense intracerebral lesions (not shown) thought to be subacute hemorrhagic infarcts secondary to an underlying vasculitis or a thromboembolic phenomenon, hence a lumbar puncture was done. The CSF had 35 cells/mm3, positive Cryptococcus antigen test, and positive Indian and Pandy's test. As a way of ruling out autoimmune vasculitis, Perinuclear Anti-Neutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibodies (p-ANCA), Cytoplasmic-ANCA, and Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibodies (ANA) profiles were performed which were all negative. Carotid Doppler ultrasound was also done for the same purpose and was unremarkable.

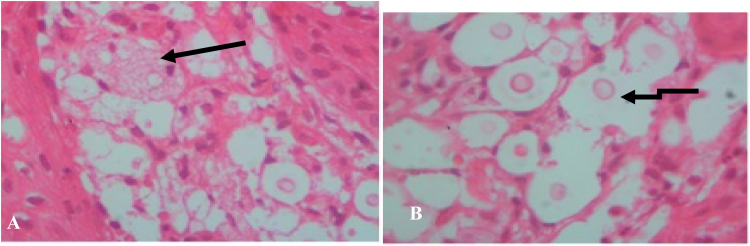

The biopsy was taken from the nostril, fixed in 10% formalin and sent for histological examination. The sample was processed and embedded in paraffin and section was stained by hematoxylin and eosin. Histological findings of the biopsied nodule revealed a skin with underlying chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate with foamy macrophages (Fig. 2A), scattered round fungal bodies with a thick capsule and a halo indicative of fungal organisms (Fig. 2B). Neither granuloma nor giant cells could be identified. The fungal bodies were positive for Periodic Acid Schiff (not shown). The diagnosis of fungal infection suggestive for Cryptococcus spp. was made.

Fig. 2.

Histological findings (A) Foamy macrophages in a background (Arrow) (B) Scattered round bodies with thick capsule and a halo (arrows) indicative of fungal cells.

Until day 5 the patient was still on the management of bacterial meningitis with no improvement. The CSF culture, India ink stain and Cryptococcus antigen test on this day confirmed the cryptococcal infection and the patient was started on CM management as per BMC protocol with 1.2 g i.v. fluconazole (induction), 8 weeks of 800 mg p.o. fluconazole (consolidation), and a maintenance dose of 400 mg p.o. for one year. As part of CM management protocol, serial lumbar punctures were performed on day 0 of CM diagnosis, day 1, 3 and 7 and 14 to control the management and reduce intracranial pressure (ICP) of which at the 14th day post i.v. fluconazole, the CSF culture remained negative.

Antifungal susceptibility was tested using broth microdilution method according to EUCAST guidelines [6]. The isolate was susceptible to fluconazole (0.063 μg/ml), caspofungin (0.004 μg/ml), micafungin (0.004 μg/ml), posaconazole (0.008 μg/ml) and voriconazole (0.031 μg/ml). The molecular characterization using URA3-RFLP typed the isolate as Cryptococcus deuterogattii (genotype AFLP6/VGII) among the newly categorized species of C. gattii [7]. The source of the agent remained unclear, as the patient did not recall any exposure to bird droppings, or to eucalyptus (or similar) trees.

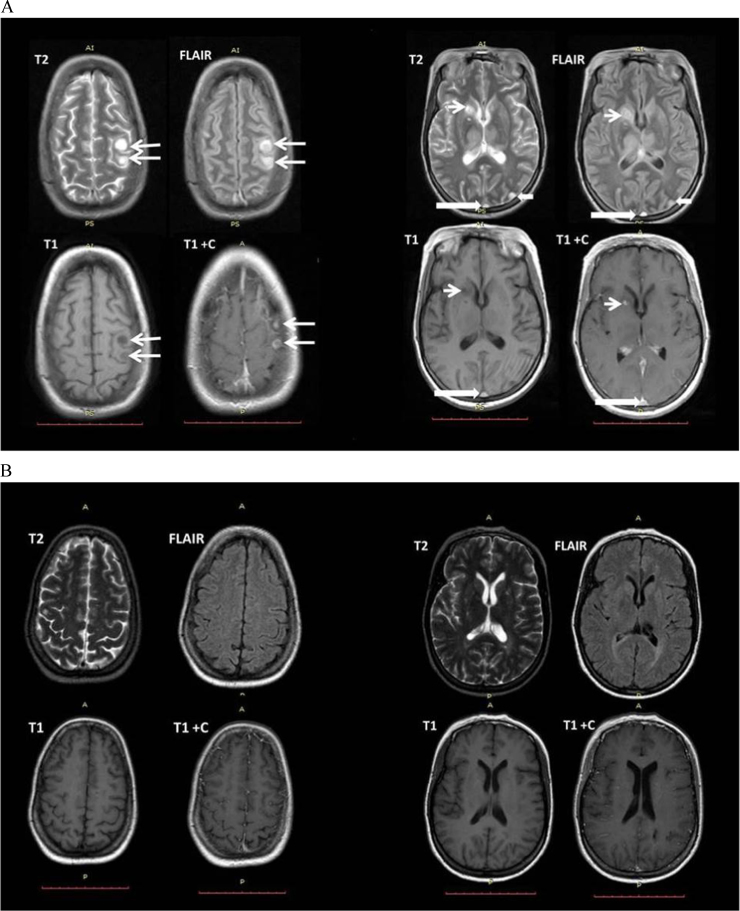

After 14 days of induction with i.v. fluconazole, the patient developed seizures upon which MRI was requested and demonstrated multiple circumscribed T2 and FLAIR hyperintense signal, FLAIR hyperintense with internal nodular and peripheral capsule isointense signal, T1 hypointense cystic lesions with TI post-contrast nodular enhancement, suggestive of infective abscesses or granulomas (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

MRI findings. (A) MRI T2, FLAIR, T1, T1 post contrast sequences showing multiple focal lesions within the left high parietal lobe (long thin white arrow), left occipital lobe (short thick white arrow), right caudate nucleus (short thin white arrow), with dural venous thrombosis (long thick white arrow). (B)MRI T2, FLAIR, T1, T1 post contrast sequences showing interval resolution of almost all of the lesions 11 months post treatment.

Five months later, the patient was seen at the clinic; she was on her maintenance dose with only a single complaint of blurred vision of which one year later had progressed to bilateral loss of vision. One year later, a follow up MRI demonstrated almost complete resolution of most of the lesions post treatment (Fig. 3B).

3. Discussion

The understanding of existence of non-HIV associated CM among clinicians in Sub-Saharan Africa including Tanzania is rare due to a limited documentation of cases, as seen in this patient. The later context results into low index of suspicion [5] which in turn results into either a delay as demonstrated at a tertiary healthcare facility (BMC). In all visits to the three different hospitals prior to BMC admission, the diagnosis of CM was not made, even at BMC it was not suspected in the initial work up on the patient. Moreover, poor work-up of patients presenting with fever might have contributed to the delay of CM treatment in this patient regardless of the low yield (28%) of fungal blood culture in immunocompetent people [8].

Unlike reported cases of cryptococcosis in other immunocompetent people, our patient did not present with altered mental status, though fever was present. Our finding is similar to a study in Thailand where 57% of the HIV-negative patients with cryptococcosis had fever [8]. The fever in our case may have resulted from high levels of proinflammatory cytokines induced by C. gattii compared to low responses induced by C. neoformans [9], which, however, was not tested.

Like in other CM cases [10], our patient presented with reduced visual acuity which can be explained by the increased ICP. Of note, despite the clearance of infection and reduced opening pressure as observed in serial lumbar punctures, the patient progressed into loss of vision which can either be a result of optical nerve involvement due to infection [11] or exaggerated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) following treatment which damaged the optical nerve [12]. Left occipital lobe or visual cortex involvement shown on MRI may possibly explain the visual loss.

The occurrence of convulsions immediately after induction phase in our patient can be explained by the cryptococcoma that were formed as a result of IRIS following treatment. For cryptococcal capsule material downregulation of the immune system, hence masking the inflammatory responses, has been described [13].

The C. deutrogattii in this study was typed as AFLP6/VGII with the involvement of CNS similar to the clinical isolates from Brazil [14]. Unlike the Brazilian isolate which had a fluconazole MIC of 2.07 μg/ml, the C. deutrogattii isolate from our patient was susceptible to fluconazole. Different geographical locations can contribute to the epidemiological differences observed. This is further supported by the report of C. deutrogattii in Ivory Coast of which the isolate was susceptible to fluconazole [15]. To our knowledge, this case is only be the second in Africa and the first in East Africa [16], highlighting the possible underreporting of C. deuterogattii cases in Africa due to limited molecular diagnostics.

Although there is a documentation of C. gattii infection in non-HIV patients with idiopathic CD4 lymphocytopenia [17], given the limited facilities in our setting, we could not establish any form of immunosuppression in this patient and her CD4 count was within normal range.

In conclusion, cryptococcosis among HIV-negative patients is not rare in Sub-Saharan Africa, including Tanzania. High index of suspicion deduced from proper history taking, coupled with proper work-up of patients presenting with fever and neurological symptoms might increase the number of detected infections. Early detection of CM and introduction of appropriate antifungal therapy may improve clinical outcomes. Further studies are needed to gather evidence in the benefit of different CM management regime in HIV negative patients including introduction of immunosuppression therapy to counteract possible effect of IRIS.

Acknowledgements

We would like to recognize the technical support of the Institute of Medical Microbiology, University Medical Center Goettingen, Germany, for phenotypic and molecular characterization of the isolate. The authors thank Agnieszka Goretzki for expert technical support.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

There are none.

Ethical form

Please note that this journal requires full disclosure of all sources of funding and potential conflicts of interest. The journal also requires a declaration that the author(s) have obtained written and signed consent to publish the case report from the patient or legal guardian(s).

The statements on funding, conflict of interest and consent need to be submitted via our Ethical Form that can be downloaded from the submission site www.ees.elsevier.com/mmcr. Please note that your manuscript will not be considered for publication until the signed Ethical Form has been received.

References

- 1.Wajanga B.M., Kalluvya S., Downs J.A., Johnson W.D., Fitzgerald D.W., Peck R.N. Universal screening of Tanzanian HIV-infected adult inpatients with the serum cryptococcal antigen to improve diagnosis and reduce mortality: an operational study. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2011;14(1):48. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-14-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen S., Sorrell T., Nimmo G., Speed B., Currie B., Ellis D., Marriott D., Pfeiffer T., Parr D., Byth K. Epidemiology and host-and variety-dependent characteristics of infection due to Cryptococcus neoformans in Australia and New Zealand. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2000;31(2):499–508. doi: 10.1086/313992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kidd S., Hagen F., Tscharke R., Huynh M., Bartlett K., Fyfe M., Macdougall L., Boekhout T., Kwon-Chung K., Meyer W. A rare genotype of Cryptococcus gattii caused the cryptococcosis outbreak on Vancouver Island (British Columbia, Canada) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101(49):17258–17263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402981101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moosa M., Coovadia Y. Cryptococcal meningitis in Durban, South Africa: a comparison of clinical features, laboratory findings, and outcome for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive and HIV-negative patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1997;24(2):131–134. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitha M., Naicker P., Mahida P. Disseminated Cryptococcosis in an HIV-negative patient in South Africa: the elusive differential diagnosis. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2010;4(08):526–529. doi: 10.3855/jidc.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lass-Flörl C., Cuenca-Estrella M., Denning D., Rodriguez-Tudela J. Antifungal susceptibility testing in Aspergillus spp. according to EUCAST methodology. Med. Mycol. 2006;44(Supplement_1):S319–S325. doi: 10.1080/13693780600779401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugita T., Cho O., Takashima M. Current status of taxonomy of pathogenic yeasts. Med. Mycol. J. 2017;58(3):J77–J81. doi: 10.3314/mmj.17.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiertiburanakul S., Wirojtananugoon S., Pracharktam R., Sungkanuparph S. Cryptococcosis in human immunodeficiency virus-negative patients. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2006;10(1):72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoffelen T., Illnait-Zaragozi M.-T., Joosten L.A., Netea M.G., Boekhout T., Meis J.F., Sprong T. Cryptococcus gattii induces a cytokine pattern that is distinct from other cryptococcal species. PloS One. 2013;8(1):e55579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williamson P.R., Jarvis J.N., Panackal A.A., Fisher M.C., Molloy S.F., Loyse A., Harrison T.S. Cryptococcal meningitis: epidemiology, immunology, diagnosis and therapy. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2017;13(1):13. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moodley A., Rae W., Bhigjee A., Connolly C., Devparsad N., Michowicz A., Harrison T., Loyse A. Early clinical and subclinical visual evoked potential and Humphrey's visual field defects in cryptococcal meningitis. PloS One. 2012;7(12):e52895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiggundu R., Rhein J., Meya D.B., Boulware D.R., Bahr N.C. Unmasking cryptococcal meningitis immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in pregnancy induced by HIV antiretroviral therapy with postpartum paradoxical exacerbation. Med. Mycol. case Rep. 2014;5:16–19. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Meara T.R., Alspaugh J.A. The Cryptococcus neoformans capsule: a sword and a shield. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012;25(3):387–408. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00001-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herkert P., Hagen F., de Oliveira Salvador G., Gomes R., Ferreira M., Vicente V., Muro M., Pinheiro R., Meis J., Queiroz-Telles F. Molecular characterisation and antifungal susceptibility of clinical Cryptococcus deuterogattii (AFLP6/VGII) isolates from Southern Brazil. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016;35(11):1803–1810. doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2731-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kassi F.K., Drakulovski P., Bellet V., Krasteva D., Gatchitch F., Doumbia A., Kouakou G.A., Delaporte E., Reynes J., Mallié M. Molecular epidemiology reveals genetic diversity among 363 isolates of the Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii species complex in 61 Ivorian HIV‐positive patients. Mycoses. 2016;59(12):811–817. doi: 10.1111/myc.12539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herkert P.F., Hagen F., Pinheiro R.L., Muro M.D., Meis J.F., Queiroz-Telles F. Ecoepidemiology of Cryptococcus gattii in developing countries. J. Fungi. 2017;3(4):62. doi: 10.3390/jof3040062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen S.C., Slavin M.A., Heath C.H., Playford E.G., Byth K., Marriott D., Kidd S.E., Bak N., Currie B., Hajkowicz K. Clinical manifestations of Cryptococcus gattii infection: determinants of neurological sequelae and death. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;55(6):789–798. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]