Abstract

Objectives

To determine dementia prevalence and costs attributable to dementia using Veterans Health Administration (VHA) data with and without Medicare data.

Data Sources

VHA inpatient, outpatient, purchased care and other data and Medicare enrollment, claims, and assessments in fiscal year (FY) 2013.

Study Design

Analyses were conducted with VHA data alone and with combined VHA and Medicare data. Dementia was identified from a VHA sanctioned list of ICD‐9 diagnoses. Attributable cost of dementia was estimated using recycled predictions.

Data Collection

Veterans age 65 and older who used VHA and were enrolled in Traditional Medicare in FY 2013 (1.9 million).

Principal Findings

VHA records indicated the prevalence of dementia in FY 2013 was 4.8 percent while combined VHA and Medicare data indicated the prevalence was 7.4 percent. Attributable cost of dementia to VHA was, on average, $10,950 per veteran per year (pvpy) using VHA alone and $6,662 pvpy using combined VHA and Medicare data. Combined VHA and Medicare attributable cost of dementia was $11,285 pvpy. Utilization attributed to dementia using VHA data alone was lower for long‐term institutionalization and higher for supportive care services than indicated in combined VHA and Medicare data.

Conclusions

Better planning for clinical and cost‐efficient care requires VHA and Medicare to share data for veterans with dementia and likely more generally.

Keywords: Health care costs, medicare, medicaid, VA Health Care System

Dementia has been reported to carry a significant cost burden to governments and to individuals (Hurd et al. 2013; Kelley et al. 2015). For the United States’ Veterans Health Administration (VHA), it is important to understand the expected costs of providing care to veterans with dementia, especially as the prevalence of dementia is expected to rise (VHA 2013). However, patients with dementia often use Medicare services in addition to VHA services. Previous work has shown substantial under‐diagnosis of disease risk in veterans who used both Medicare and VHA services, when only one data source was used (Tseng et al. 2004; Rosen et al. 2005; Byrne et al. 2006). This study aims to examine the cost burden to VHA alone and total costs to both VHA and Medicare of veterans with dementia identified in the VHA alone (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs 2015) and those identified in either VHA or Medicare (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs 2016).

There are significant differences in services covered by Medicare and VHA, with VHA covering a wider range of services (U.S. General Accounting Office 1994). Medicare pays for primary and consultant care and acute and postacute care, but does not pay for long‐term care. VHA provides a broad array of community based services that are especially relevant to patients with dementia, such as homemaker services, adult day health care and home based primary care (HBPC) in addition to the services that are provided by Medicare. VHA also covers long‐term nursing home care for a significant subset of enrolled veterans. Thus, VHA covers many services which, for nonveterans, may be covered by Medicaid, other insurance, or out of pocket.

Medicare‐enrolled veterans rely on VHA services to varying degrees (U.S. General Accounting Office 1994; Shen et al. 2003; Weeks et al. 2005; Hynes et al. 2007; Liu et al. 2010). The combinations of VHA‐provided and Medicare‐reimbursed care that exist are determined by many factors, including geographic access, timeliness of access, patient cost, type of service, and perceived quality (Borowsky and Cowper 1999; Nayar, Yu, and Apenteng 2014). Although many patients with dementia will have needs for services that are not covered by Medicare, some veterans with dementia still rely on Medicare for significant portions of their medical care.

The existence of such combined care means that examination of prevalence and costs associated with dementia among veterans requires using data from both VHA and Medicare. Further complicating analysis, dementia might not be well‐documented in VHA or Medicare claims data alone due to under reporting, under diagnosis in claims data, or use of multiple health care systems (Tseng et al. 2004; Rosen et al. 2005; Byrne et al. 2006; Taylor et al. 2009; Lin et al. 2010). Finally, it is important to recognize that veterans who use both systems are likely to be more expensive (Fisher and Welch 1995; Wright et al. 1999; Trivedi et al. 2012), and may suffer inferior care due to uncoordinated care across the systems (Pizer and Gardner 2011; Tarlov et al. 2012; Cooper et al. 2015).

Attributable cost of dementia, i.e., cost attributed to dementia after accounting for confounding factors, is important to estimate especially since dementia is often only one among multiple chronic conditions. Yu et al. (2003a) used regression methods to study the marginal effect of chronic conditions on health care costs in the VHA health care system in 1999 and found that the attributable annual cost of dementia was $11,000. However, that paper did not specifically focus on dementia, and included only Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia but not other dementias (e.g., frontotemporal, Lewy bodies). Yoon et al. (2011) studied recent trends in VHA chronic condition spending and found that total spending for Alzheimers’ disease and vascular dementia declined, suggesting that this may be due to declining costs of treatment. The lower average attributable cost per veteran with dementia may have only been partially reflected as estimates were based only on VHA costs and Alzheimers’ disease and vascular dementia diagnosis, potentially missing veterans with other dementias, and with diagnosed dementia and services paid outside VHA.

This paper examines the impact of adding Medicare data to VHA data on the identification of veterans with dementia, and the impact of identifying additional veterans with dementia on the estimates of per veteran per year (pvpy) attributable costs of dementia to the VHA and in total to VHA and Medicare. The addition of Medicare data addresses an important limitation of earlier analysis, which used VHA data alone, because a considerable proportion of VHA enrollees older than 65 years are dually enrolled in VHA and Medicare. Identification of veterans with dementia is critical when planning and designing health services because dementia is associated with greater risk of improper medication management, greater need for patient and caregiver support (Alzheimer's Association 2017) and greater use of acute services (Phelan et al. 2012).

This study aims to (1) use a comprehensive list of ICD‐9 codes to obtain more inclusive estimates of the prevalence of any dementia among veterans; (2) characterize the difference between identification of veterans with dementia using VHA data alone or combined with Medicare data; and (3) obtain more complete estimates of costs attributed to dementia among veterans who used the VHA.

Methods

This work was conducted at the request of VHA Office Geriatrics & Extended Care (GEC). Following VHA guidelines, this paper received approval for an Attestation which allowed it to be submitted to peer‐reviewed publication.

Data and Cohort

This study used the VHA Office of Geriatrics & Extended Care Data Analysis Center (GECDAC) Core Files (GCF) that use VHA and Medicare data in FY 2013. VHA utilization and cost data were derived from inpatient stay records, outpatient encounter data, and purchased care claims. VHA enrollment, vital statistics, socio‐demographic data were obtained from the Corporate Data Warehouse (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs 2014). Access to Medicare data was obtained from VHA's Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Analysis Center under Data Use Agreement and included enrollment data (from the Master Beneficiary Summary File), utilization and cost data from CMS’ Standard Analytic Files (inpatient, outpatient, skilled nursing facility, hospice, home health, part D medications, durable medical equipment). Minimum Data Set (MDS) from nursing homes in the community, VA nursing homes and State Veterans Homes were used to identify long‐term institutionalization (LTI). VHA and Medicare data were combined using Social Security Number (SSN).

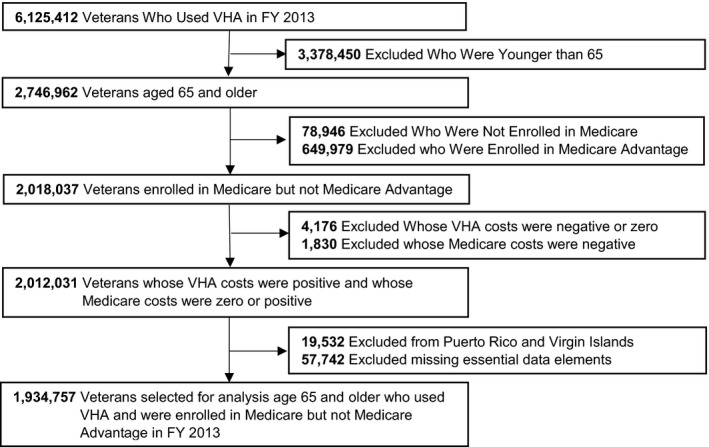

Figure 1 describes the study cohort. Among veterans age 65 and older, we excluded veterans who were not enrolled in Medicare (2.9 percent), who were enrolled in Medicare Advantage (23.7 percent) due to incomplete data, whose VHA costs were negative or zero (0.2 percent) or whose Medicare costs were negative (0.1 percent). We also excluded veterans from Puerto Rico and Virgin Islands (0.7 percent) and those who were missing essential data elements (2.1 percent). The final cohort included 1,934,757 veterans age 65 and older who used VHA and who were enrolled in Traditional Medicare in FY 2013.

Figure 1.

Selection of Sample (N = 1,934,757)

Dependent Variables

The main outcomes were total VHA health care expenditures and combined Medicare and VHA expenditures in FY 2013. We refer to expenditures as ‘costs’. Costs were adjusted by the consumer price index (CPI) to 2016 dollars and to medical area wage index. We truncated VHA and Medicare costs at the 99th percentile to eliminate the impact of outliers on the estimates. Sensitivity analysis with nontruncated cost data were conducted.

VHA and Medicare differ in many aspects, leading to differences in practice patterns and access to care. In order to understand underlying causes of the differences in costs we also examined the association of dementia with health care service utilization. Three types of services related to long‐term care: VHA and Medicare supportive services (adult day health care, home maker/home health aide, respite, Program of All‐Inclusive Care for the Elderly, community residential care, Veterans Directed Home and Community Based Services), LTI,1 and non‐VHA/non‐Medicare paid nursing home care. We used the Residential History File that uses MDS nursing home resident assessments to identify nursing home care not paid by VHA or Medicare (Intrator et al. 2011). We also examined differences in acute inpatient care and end‐of‐life care among decedents.

Independent Variables

The primary independent variable was a dementia diagnosis identified in VHA alone and in combined VHA and Medicare data. Dementia was identified from a VHA sanctioned list of ICD‐9 diagnoses (046xx, 290xx, 291.2, 292.82, 294xx, and 331xx). We created two independent variables: (1) any dementia recorded in VHA using VHA data alone, and (2) any dementia recorded in either VHA or Medicare data.

Model Covariates

Additional variables were included in the statistical models to describe the population and adjust for potential confounders in the relationship between dementia and health care costs.

We used diagnoses of conditions associated with costs suggested by others (Yu et al. 2003a; Bynum et al. 2004; Yoon et al. 2011; Centers for Medicare and Medicare Services 2017): (1) diagnoses of comorbidities that were identified among patients with dementia in the literature, such as depression, heart disease, schizophrenia; (2) diagnoses that are costly such as AIDS/HIV, spinal cord injury; and (3) diagnoses that are prevalent among veterans, such as drug dependence/abuse, alcohol dependence/abuse, and post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Table S1 lists all 34 conditions that were used in the model and the ICD‐9 codes used to identify them.

We also controlled for socio‐demographic variables including age, gender, race, and marital status. Wealth and income were captured through indicators of Medicaid eligibility in the year, VHA priority status (that determines VHA benefit coverage), and rurality of residence. Risk of LTI was determined by the JEN Frailty Index (JFI) (JEN Associates 2011).

Finally, we created five variables to capture market characteristics that might impact the levels of costs and utilization of Medicare and VHA: percent population age 75 and older, number of nursing home beds to 1,000 population age 75 and older, number of hospital beds per 1,000 population, number of active physicians per 1,000 population in the county, and percent of state's average Medicaid spending on home and community based services (HCBS) (Ng et al. 2016). The summary statistics of market characteristics are listed in the Table S2.

Statistical Modeling

Regression Models

This paper estimated the overall population effect of dementia on costs using generalized estimation equation (GEE) models with gamma distribution, natural logarithm link and exchangeable working correlation with variance clustered at the 141 VHA Medical Center (VAMC). For dichotomous outcomes including whether the veteran had any Medicare cost and any health care service utilization of five types (supportive services, acute inpatient, LTI, non‐VHA/non‐Medicare paid nursing home care, and end‐of‐life services among decedents) we used GEE models with binomial distribution and logit link and with variance clustered at VAMC. All GEE models were offset by the natural logarithm of the number of days alive in FY2013.

Using VHA data alone, we ran models for VHA costs to test the association of any dementia reported in VHA. For combined VHA and Medicare data, we ran models testing the association of any dementia reported in either VHA or Medicare with VHA costs or combined VHA and Medicare costs. Since only 68 percent of veterans had any Medicare costs we used 2‐stage modeling for testing the association of a dementia diagnosis with Medicare costs, first estimating a model for any cost, and then, among those with Medicare costs, the association with the natural logarithm of costs. In total, five models were estimated.

Calculation of Attributable Cost of Dementia

The attributable cost of dementia is the marginal effect of dementia on cost. This was estimated using the method of recycled prediction (Graubard and Korn 1999; Li and Mahendra 2016). This method uses the estimated coefficients from the GEE model to predict health care costs for each veteran assuming the veteran had dementia and assuming the veteran did not have dementia, holding all other characteristics as observed. The difference between the predicted costs assuming the veteran had dementia compared to the predicted costs assuming the veteran did not have dementia is the incremental cost attributed to dementia for that veteran. The attributable cost of dementia is then calculated as the sample average of all veterans’ differences of predicted costs.

Results

Summary Statistics

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of characteristics for the FY 2013 veteran cohort, with priority group, and comorbidities listed in the Table S3. Using VHA data alone, we identified 4.8 percent of veterans with a dementia diagnosis. Using the combined VHA and Medicare data we identified 7.4 percent of veterans with a dementia diagnosis.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Characteristics among Veterans Age 65 and Older Who Used Veteran Health Administration (VHA) by VHA or Combined VHA and Medicare Reported Dementia in FY 2013

| VHA Data Alone* | Combined VHA and Medicare Data† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia Diagnosis (N = 92,970) | No Dementia Diagnosis (N = 1,841,787) | Dementia Diagnosis (N = 142,951) | No Dementia Diagnosis (N = 1,791,806) | |

| Prevalence of dementia (%) | 4.8% | – | 7.4% | – |

| Average costs (mean/SD) | ||||

| VHA | $23,305 (31,318) | $8,083 (16,440) | $18,025 (28,277) | $8,080 (16,402) |

| Medicare | – | – | $23,539 (27,213) | $9,535 (17,610) |

| Combined VHA and Medicare | – | – | $39,230 (37,740) | $14,673 (22,719) |

| Health care services (%) | ||||

| Any supportive services | 19.7 | 1.8 | 15.3 | 1.7 |

| Any acute inpatient admissions | 31.7 | 15.0 | 33.4 | 14.4 |

| Any long‐term institutionalization | 12.0 | 1.1 | 12.9 | 0.7 |

| Any non‐VHA/non‐Medicare paid NH care | 9.2 | 1.2 | 11.4 | 0.8 |

| Any end of life services among decedents | 61.0 | 47.4 | 57.5 | 46.3 |

| Socio‐demographic (Column %) | ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| 65–74 | 19.8 | 55.9 | 17.8 | 57.1 |

| 75–84 | 40.5 | 30.0 | 40.3 | 29.8 |

| 85+ | 39.7 | 14.1 | 41.9 | 13.2 |

| Male | 97.6 | 98.2 | 97.7 | 98.3 |

| White | 75.6 | 75.6 | 75.3 | 75.6 |

| Married | 60.4 | 64.8 | 61.2 | 64.9 |

| Rurality of residence | ||||

| Highly urban | 45.8 | 39.9 | 45.0 | 39.8 |

| Urban | 16.8 | 16.6 | 17.5 | 16.5 |

| Rural | 36.1 | 41.7 | 36.3 | 41.8 |

| Highly Rural | 1.3 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 1.9 |

| Health system | ||||

| Medicaid | 13.4 | 5.1 | 14.9 | 4.8 |

| Any Medicare costs | 82.6 | 67.0 | 88.7 | 66.1 |

| % total costs paid by Medicare | 37.2 | 35.7 | 51.9 | 34.5 |

| Risk score | ||||

| JFI (%) | ||||

| 0–2 | 5.1 | 33.1 | 4.1 | 33.9 |

| 3–5 | 34.6 | 48.1 | 29.9 | 48.8 |

| 6–8 | 42.8 | 16.0 | 44.5 | 15.1 |

| 9+ | 17.5 | 2.3 | 21.5 | 1.6 |

| Died (%) | 13.3 | 3.4 | 15.9 | 3.0 |

The study cohort is veterans age 65 and older who used VHA and were enrolled in Medicare but not Medicare Advantage in FY 2013.

*Under “VHA Data Alone” column dementia, risk scores and comorbidities were computed using VHA data alone.

†Under “Combined VHA and Medicare Data” columns dementia, risk scores and comorbidities were computed using VHA and Medicare data.

JFI, JEN Frailty Index; NH, nursing home.

Compared to veterans with no dementia diagnosis, veterans with dementia were more likely to be older and Medicaid eligible, slightly less likely to live in rural areas, more likely to have higher JFI scores and higher comorbidity burden. Among veterans identified with dementia in VHA 13.3 percent died and 61 percent of decedents used end‐of‐life care; using combined data, these figures were 15.9 percent and 57.5 percent respectively.

Among veterans with a dementia diagnosis recorded in VHA the average VHA costs of care were $23,305. Veterans with a dementia diagnosis in either VHA or Medicare had an average cost to VHA of $18,025 and combined VHA and Medicare costs of $39,230.

Among veterans with dementia, inpatient admission rate was 31.7 percent using VHA data and 33.4 percent using combined data; LTI rate was 12.0 percent and 12.9 percent per year using VHA or combined data, respectively. Veterans with dementia had higher use of supportive care services as identified in VHA alone compared to combined data (19.7 percent vs. 15.3 percent respectively).

Attributable Cost of Dementia

Table 2 presents the unadjusted results comparing average difference in costs of veterans with dementia and veterans without dementia and results of the recycled prediction calculating attributable cost of dementia as the difference between the model‐based predicted costs assuming all veterans had dementia compared to assuming none had dementia, holding all other characteristics as observed. Veterans with dementia had higher unadjusted and adjusted costs than veterans without dementia.

Table 2.

Attributable Cost of Dementia among Veterans Age 65 and Older Who Used Veteran Health Administration (VHA) Using VHA Data Alone or Combined VHA and Medicare Data in FY 2013

| VHA Data Alone† | Combined VHA and Medicare Data‡ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis in VHA(N = 92,970) | Diagnosis in VHA or in Medicare(N = 142,951) | |||

| Unadjusted Attributable Cost | Adjusted Attributable Cost | Unadjusted Attributable Cost | Adjusted Attributable Cost | |

| To VHA | $15,222*** (15,107–15,336) | $10,950*** (10,916–10,984) | $9,945*** (9,850–10,039) | $6,662*** (6,650–6,674) |

| To Medicare | $14,003*** (13,896–14,111) | $5,522*** (5,509–5,535) | ||

| To combined VHA and Medicare | – | – | $24,558*** (24,428–24,688) | $11,285*** (11,263–11,306) |

The study cohort is veterans age 65 and older who used VHA and were enrolled in Medicare but not Medicare Advantage in FY 2013.

We use GEE models with gamma distribution and natural logarithm link and exchangeable working correlation with variance clustered at VAMC. The models are offset by the natural logarithm of the number of days alive in FY 2013.

Recycled predictions are used to calculate attributable cost of dementia based on estimates from GEE models: (1) predict health care costs for each veteran assuming the veteran had dementia and assuming the veteran did not have dementia, holding all other characteristics as observed; (2) calculate the incremental cost attributed to dementia for that veteran by taking the difference between the predicted costs assuming the veteran had dementia compared to the predicted costs assuming the veteran did not have dementia. Attributable cost of dementia is calculated as the sample average of all veterans’ incremental cost attributed to dementia. Adjusted attributable cost of dementia and 95% CI are reported.

Unadjusted attributable costs and 95% CI were reported. T‐test was used to compare the differences in unadjusted costs between patients with dementia and patients without dementia.

*Significant at 10%; **significant at 5%; ***significant at 1%.

VHA and Medicare costs were CPI adjusted to 2016 with Wage Index (2/3) and truncated at the 99th percentile.

Control variables include demographic variables (age groups, gender, marital status, race), rurality of residence (highly urban, urban, rural, highly rural), JFI scores, Medicaid eligibility and market characteristics (% population ≥75, # nursing home beds per 1,000 population, # hospital beds per 1,000 population and # active physicians per 1,000 population in the county, and % state Medicaid spending on HCBS).

†Under “VHA Data Alone” column dementia, risk scores and comorbidities were computed using VHA data alone.

‡Under “Combined VHA and Medicare Data” columns dementia, risk scores and comorbidities were computed using combined VHA and Medicare data.

Using VHA data alone, the attributable cost of dementia to VHA was $10,950 pvpy (95 percent confidence interval, CI: $10,916–$10,984), and $6,662 (95 percent CI: $6,650–$6,674) when estimated with combined VHA and Medicare data. Using the combined VHA and Medicare data, the total attributable cost of dementia to VHA and Medicare was $11,285 pvpy (95 percent CI: $11,263–$11,306). (Table S4 presents the estimated coefficients of the association of dementia with costs from each of the five GEE models. Table S5 presents the model‐based predicted costs assuming all veterans had dementia and assuming none had dementia.)

Sensitivity analysis with the nontruncated cost data is presented in Table S6. When using the original nontruncated costs compared to using the truncated costs, the attributable cost to VHA using VHA data alone were $12,821 pvpy (17 percent higher than the truncated results) and attributable cost to VHA and Medicare using combined VHA and Medicare data were $12,583 (12 percent higher than the truncated data results). By presenting results from the truncated data we have provided more conservative estimates.

Health Care Utilization Attributed to Dementia

Table 3 presents the odds ratios of the association between dementia and use of supportive care services, acute inpatient care, LTI, non‐VHA/non‐Medicare paid nursing home care, and end‐of‐life care among decedents. Veterans with a dementia diagnosis had a higher probability of using all the services using VHA data alone or combined VHA and Medicare data than veterans without a dementia diagnosis. Compared to using VHA data alone, utilization attributed to dementia using combined VHA and Medicare data was higher for LTI [Adjusted odds ratio, AOR: 7.145 (95 percent CI: 6.755–7.557) vs. 5.338 (95 percent CI: 5.042–5.651)] and non‐VHA/non‐Medicare paid nursing home care [AOR: 4.676 (95 percent CI: 4.454–4.910) vs. 3.427 (95 percent CI: 3.244–3.622)], but lower for supportive care services [AOR: 3.987 (95 percent CI: 3.760–4.229) vs. 5.211 (95 percent CI: 4.919–5.520)].

Table 3.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Odds Ratios of the Association of Dementia with Health Care Services Received by Veterans Age 65 and Older Who Use Veteran Health Administration (VHA) Using VHA Data Alone or Combined VHA and Medicare Data in FY 2013

| VHA Data Alone‡ | Combined VHA and Medicare Data†† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Odds Ratio | Adjusted Odds Ratio† | Unadjusted Odds Ratio | Adjusted Odds Ratio† | |

| Any supportive services | 13.766*** (13.026–14.548) | 5.211*** (4.919–5.520) | 11.217*** (10.606–11.864) | 3.987*** (3.760–4.229) |

| Any acute inpatient admissions | 2.739*** (2.671–2.808) | 1.499*** (1.462–1.538) | 3.156*** (3.096–3.217) | 1.513*** (1.486–1.541) |

| Any long‐term institutionalization | 12.743*** (11.992–13.542) | 5.338*** (5.042–5.651) | 21.323*** (20.137–22.578) | 7.145*** (6.755–7.557) |

| Any non‐VHA/non‐Medicare paid NH care | 8.542*** (8.133–8.972) | 3.427*** (3.244–3.622) | 16.659*** (15.878–17.48) | 4.676*** (4.454–4.910) |

| Any end of life care among decedents | 1.748*** (1.670–1.830) | 1.668*** (1.591–1.749) | 1.563*** (1.498–1.630) | 1.574*** (1.505–1.646) |

| Died | 4.500*** (4.361–4.644) | 2.086*** (2.023–2.152) | 6.550*** (6.393–6.711) | 2.393*** (2.332–2.456) |

The study cohort is veterans age 65 and older who used VHA and were enrolled in Medicare but not Medicare Advantage in FY 2013.

We use GEE models with binomial distribution and logit link function and with variance clustered at VAMC. The models are offset by the natural logarithm of the number of days alive in FY 2013.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios and 95% CI are reported. *Significant at 10%; **significant at 5%; ***significant at 1%.

†Control variables in the adjusted models include demographic variables (age groups, gender, marital status, race), rurality of residence (highly urban, urban, rural, highly rural), JFI scores, Medicaid eligibility and market characteristics (% population ≥75, # nursing home beds per 1,000 population, # hospital beds per 1,000 population and # active physicians per 1,000 population in the county, and % state Medicaid spending on HCBS).

‡Under “VHA Data Alone” column dementia, risk scores and comorbidities were computed using VHA data alone.

††Under “Combined VHA and Medicare Data” columns dementia, risk scores and comorbidities were computed using combined VHA and Medicare data.

Discussion

Among veterans age 65 and older who used VHA and who were enrolled in Traditional Medicare in FY 2013, the proportion of veterans with a dementia diagnosis recorded in either VHA or Medicare was 7.4 percent compared to only 4.8 percent recorded in VHA. The prevalence of dementia using the combined data was closer to the dementia prevalence among veterans estimated by VHA to be 9.6 percent (GEC 2013).

The total attributable combined cost of dementia (to VHA and Medicare) using the combined diagnoses was, on average, $11,285 pvpy only 3 percent higher than the VHA costs estimated using VHA diagnoses alone ($10,950). The total attributable costs of dementia to VHA using the combined diagnoses data was $6,662, 39 percent lower than that estimated with VHA data alone. The similar attributable costs from VHA and combined data may be due to the missed 35 percent (N = 49,981) veterans identified with dementia using VHA data alone who had a low cost in the VHA as they were more reliant on Medicare (Table S7).

The total adjusted health care cost attributed to dementia carried by VHA estimated using VHA data alone was $1 billion. Including the costs of veterans identified through Medicare claims raised costs carried by VHA to $1.3 billion. The total health care costs to VHA and Medicare attributed to dementia was $1.6 billion using the combined data. These large differences can skew budgetary planning leading to unintended consequences.

Results for VHA costs presented in this paper are consistent with those presented by Yu et al. (2003a). Using VHA data alone, the average attributable cost to VHA found in this study ($10,950 pvpy) was quite close to Yu et al.'s weighted average attributable cost of Alzheimer's disease and dementia adjusted for CPI to 2016 dollars ($10,800 pvpy). Yu and colleagues did not use Medicare data. In this paper, we used a comprehensive list of dementia diagnoses and added Medicare data; we conducted a more elaborate GEE regression model and used recycled predictions.

The discrepancy between attributable cost of dementia to VHA using VHA data alone and combined VHA and Medicare data ($10,950 vs. $6,662 pvpy) is likely due to the additional 35 percent (N = 49,981) of veterans with a dementia diagnosis reported only in Medicare and not VHA. Since the combined costs were lower we deduce that VHA service utilization of these veterans was lower. As shown in Table S7, these veterans were older and sicker, more likely to have priority 8, more likely to be dual‐Medicare‐Medicaid enrolled (17.8 percent vs. 10.5 percent for dementia diagnosed only in VHA) and also more likely to use non‐VHA/non‐Medicare paid nursing home care. Veterans with dementia recorded only in Medicare are an important group to VHA planners and policy‐makers as they can potentially become an added commitment to VHA. These veterans may well benefit from more HCBS, yet only 17.8 percent were enrolled in Medicaid which provides such services. We estimate that about 6,248 more veterans who had a dementia diagnosis only in Medicare would require HCBS based on a comparison of the prevalence of use of HCBS among veterans who were not eligible for Medicaid and who had a dementia diagnosis reported in the VHA compared to veterans with a dementia diagnosis reported only in Medicare (12.5 percent difference). These 6,248 veterans and their caregivers may be among those who would benefit most from the implementation of the Choice Act since 2014 which uses a third‐party administrator to pay for services including supportive services (Matishak and Cox 2014). They might also be an important target to VA's recent “Choose Home” initiative.

Veterans with a dementia diagnosis had a higher probability of using all services compared to veterans without a dementia diagnosis, using either VHA or combined VHA and Medicare data. Long‐term institutionalization (LTI) rates (paid by VHA and other payers) were higher for veterans with dementia when estimated from the combined data than when estimated from VHA data alone (AOR: 7.145 vs. 5.338). Being able to identify individuals at risk of LTI is important for initiatives that target interventions to maintain populations in the community.

Beyond policy and planning implications, there are real clinical risks from having one‐third of veterans with dementia who used VHA but whose dementia was un‐identified in the VHA. Veterans with dementia are more susceptible to medical misadventures, such as falls, fractures, delirium and death, from use of inappropriate medications such as antipsychotic medications or medications with a high anticholinergic burden, as well as being at greater risk for complications during hospitalization (Rudolph and Marcantonio 2011; Thorpe et al. 2017). As with HCBS and LTI diversion, programs designed to reduce clinical risk for individuals with dementia are most effective if appropriately targeted.

Beyond VHA, the significant attributable cost of dementia among veterans using Medicare and VHA—$11,285 pvpy—raises questions as to why CMS does not include dementia as a condition for risk adjustment in determining payments for Medicare Advantage plans. In contrast, VHA's risk adjustment model (NOSOS) incorporates the HCC model version that includes the dementia condition categories. Combining VHA and Medicare data is also important to Medicare as an additional one‐third of veterans with dementia did not have dementia diagnosed in Medicare claims and such patients have disproportionate costs to health care systems accountable to Medicare (Sessums, McHugh, and Rajkumar 2016).

This paper has important policy implications: (1) complete identification of dementia is important in order to plan logistics that address the needs of patients with dementia in a cost‐effective manner; (2) the correct attributable cost of dementia is important for appropriate budgeting of services that are related to patients with dementia; and (3) taking other data sources into consideration is important when studying health care utilization and costs of veterans, beyond our study of dementia. Underestimating the prevalence, overestimating per capita costs, and underestimating total costs, using VHA data alone distorts health planning in general, and budget impact analyses in particular.

There are several limitations to this study. First, this study is based only on one year of data making it impossible to examine the impact of changes in coding practices and service provision. As with all observational studies this study is also limited by the variables available in administrative data, potentially excluding important confounders. However, our use of a broad range of diagnoses and risk measures, as well as our examination of the association of recorded dementia with utilization outcomes lend credibility to the findings.

Second, under diagnosis and under recording of dementia in claims data have been well documented in the literature (Taylor et al. 2009; Lin et al. 2010). However, a recent study linking Health and Retirement Study data with Medicare data showed that the reported ratio of the number of individuals identified from clinical assessment of cognitive impairment to those identified in claims diagnoses continuously declined from 2.5 in 2000 to 1.3 in 2010 (Akushevich et al. 2018). We also recognize, that the severity of dementia is likely to affect attributable costs but we did not have data on dementia severity.

Third, VHA and Medicare costs are not directly comparable. VHA costs reflect the actual VHA production costs, while Medicare “costs” are reimbursements based on insurance regulated rates. Older studies comparing VHA production costs to Medicare reimbursement rates have reported that VHA production costs were somewhat lower (Phibbs et al. 2003; Wagner, Chen, and Barnett 2003; Yu et al. 2003b). In recent years actual VHA production costs have gone up faster than Medicare reimbursement rates and this difference has been narrowed, if not entirely eliminated (unpublished data from VA Health Economics Resource Center). Thus, any bias from the difference between Medicare reimbursement rates and VHA production costs is likely to be small.

Fourth, as with prior work comparing VHA and Medicare data, there is a substantial coding disparity between the two systems. While Byrne et al. (2006) found that VHA diagnostic codes captured only one‐third of the illness burden identified among combined VHA and Medicare data, we found that in the case of dementia VHA diagnoses identified two‐thirds of the total illness burden. This may be due to VHA's provision of long‐term care services (LTI, HCBS) more intensively used by veterans with dementia which are not provided through Medicare. Conventional wisdom on the differences in coding intensity have focused on the lack of incentives within VHA to comprehensively identify diagnoses, while in Medicare not only are diagnostic codes tied to payment, but are linked to risk adjustment in CMS’ value based purchasing programs. Perhaps more importantly, due to geographic proximity, veterans who used both VHA and Medicare tended to be more reliant on Medicare for hospitalization than for outpatient care. Being more likely to be hospitalized at community hospitals where diagnoses are more comprehensively coded, may be a significant factor in capturing the additional diagnostic risk.

In conclusion, this paper demonstrates the importance of using combined VHA and Medicare data in studying the prevalence and impact of dementia on the VHA providing more accurate cost and prevalence estimates by correcting the underestimated prevalence, overestimated per capita costs, and underestimated total costs using VHA data alone. It provides figures important to planning budgets for populations with dementia.

Supporting information

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Table S1: List of ICD‐9 Codes for Comorbidities.

Table S2: Descriptive Statistics for Market Characteristics.

Table S3: Descriptive Statistics for Priority Group and Comorbidities among Veterans Age 65 and Older Who Used Veteran Health Administration (VHA) by VHA or Combined VHA and Medicare Recorded Dementia in FY 2013.

Table S4: Association of Dementia with Cost to Veteran Health Administration (VHA), Medicare or Combined among Veterans Age 65 and Older Who Used VHA By Using VHA Data alone or Combined VHA and Medicare Data in FY 2013 (GEE Model).

Table S5: Expected Costs per Veteran per Year Based on Recycled Prediction (Estimate/95% CI).

Table S6: Sensitivity Analysis – Attributable Cost of Dementia among Veterans Age 65 and Older Who Used Veteran Health Administration (VHA) Using VHA Data Alone or Combined VHA and Medicare Data in FY 2013.

Table S7: Descriptive Statistics for Characteristics among Veterans Age 65 and Older Who Used Veteran Health Administration (VHA) by VHA Only, Medicare only, and both VHA and Medicare Reported Dementia using combined VHA and Medicare data in FY 2013.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: Funding for this study was provided by the VHA Office of Geriatrics & Extended Care (GEC) to its GEC Data Analysis Center (GECDAC). This work was done independent of GEC, but in response to GEC broad request to quantify the costs of caring for Veterans with dementia. The views presented in this paper are those of the authors and do not represent those of the Veterans Health Administration.

Disclosure: None.

Disclaimer: None.

Note

LTI is defined as any episode of continuous nursing home care greater than 90 days. Interruptions for other inpatient care (of any length), emergency room, observation care, or periods in the community of up to 7 days do not terminate the episode but their duration is not accrued toward the count of days.

References

- Akushevich, I. , Yashkin A., Kravchenko J., Ukraintseva S., Stallard E., and Yashin A. I.. 2018. “Time Trends in the Prevalence of Neurocognitive Disorders and Cognitive Impairment in the United States: The Effects of Disease Severity and Improved Ascertainment.” Journal of Alzheimer's Disease (Preprint): 1–12, 53 (6): 5330–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer's Association . 2017. “2017 Alzheimer's Disease Facts and Figures.” Alzheimer's & Dementia 13 (4): 325–73. [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky, S. J. , and Cowper D. C.. 1999. “Dual Use of VA and Non‐VA Primary Care.” Journal of General Internal Medicine 14 (5): 274–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bynum, J. P. , Rabins P. V., Weller W., Niefeld M., Anderson G. F., and Wu A. W.. 2004. “The Relationship between a Dementia Diagnosis, Chronic Illness, Medicare Expenditures, and Hospital Use.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 52 (2): 187–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, M. M. , Kuebeler M., Pietz K., and Petersen L. A.. 2006. “Effect of Using Information from Only One System for Dually Eligible Health Care Users.” Medical Care 44 (8): 768–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicare Services . 2017. “Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse Chronic Conditions” [accessed on December 7, 2017]. Available at https://www.ccwdata.org/web/guest/condition-categories

- Cooper, A. L. , Jiang L., Yoon J., Charlton M. E., Wilson I. B., Mor V., Kizer K. W., and Trivedi A. N.. 2015. “Dual‐System Use and Intermediate Health Outcomes among Veterans Enrolled in Medicare Advantage Plans.” Health Services Research 50 (6): 1868–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, E. S. , and Welch H. G.. 1995. “The Future of the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care System.” Journal of the American Medical Association 273 (8): 651–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geriatrics & Extended Care . 2013. “Projections of the Prevalence of Dementia Tools” [accessed on April 7, 2018]. Available at https://www.va.gov/geriatrics/GEC_Data_Reports.asp

- Graubard, B. I. , and Korn E. L.. 1999. “Predictive Margins with Survey Data.” Biometrics 55 (2): 652–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd, M. D. , Martorell P., Delavande A., Mullen K. J., and Langa K. M.. 2013. “Monetary Costs of Dementia in the United States.” New England Journal of Medicine 368 (14): 1326–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes, D. M. , Koelling K., Stroupe K., Arnold N., Mallin K., Sohn M.‐W., Weaver F. M., Manheim L., and Kok L.. 2007. “Veterans’ Access to and Use of Medicare and Veterans Affairs Health Care.” Medical Care 45 (3): 214–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intrator, O. , Hiris J., Berg K., Miller S. C., and Mor V.. 2011. “The Residential History File: Studying Nursing Home Residents’ Long‐Term Care Histories.” Health Services Research 46 (1p1): 120–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JEN Associates . 2011. “The JEN Frailty Index” [accessed on May 1, 2018]. Available at http://www.jen.com/jfi.html

- Kelley, A. S. , McGarry K., Gorges R., and Skinner J. S.. 2015. “The Burden of Health Care Costs for Patients with Dementia in the Last 5 Years of Life.” Annals of Internal Medicine 163 (10): 729–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. , and Mahendra G.. 2016. “Using “Recycled Predictions” for Computing Marginal Effects, Statistics and Data Analysis, SAS Global Forum 2010, Paper 272‐2010.”

- Lin, P.‐J. , Kaufer D. I., Maciejewski M. L., Ganguly R., Paul J. E., and Biddle A. K.. 2010. “An Examination of Alzheimer's Disease Case Definitions using Medicare Claims and Survey Data.” Alzheimer's & Dementia 6 (4): 334–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. F. , Chapko M., Bryson C. L., Burgess J. F., Fortney J. C., Perkins M., Sharp N. D., and Maciejewski M. L.. 2010. “Use of Outpatient Care in Veterans Health Administration and Medicare among Veterans Receiving Primary Care in Community‐Based and Hospital Outpatient Clinics.” Health Services Research 45 (5p1): 1268–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matishak, M. , and Cox R.. 2014. “Senate Passes Overhaul of VA in 93‐3 Vote” [accessed on December 2, 2017]. Available at http://thehill.com/blogs/floor-action/senate/209046-senate-passes-va-overhaul

- Nayar, P. , Yu F., and Apenteng B.. 2014. “Improving Care for Rural Veterans: Are High Dual Users Different?” The Journal of Rural Health 30 (2): 139–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, T. , Harrington C., Musumeci M., and Ubri P.. 2016. “Medicaid Home and Community‐Based Services Programs: 2013 Data Update” [accessed on October 28, 2017]. Available at https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-home-and-community-based-services-programs-2013-data-update/

- Phelan, E. A. , Borson S., Grothaus L., Balch S., and Larson E. B.. 2012. “Association of Incident Dementia with Hospitalizations.” Journal of the American Medical Association 307 (2): 165–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phibbs, C. S. , Bhandari A., Yu W., and Barnett P. G.. 2003. “Estimating the Costs of VA Ambulatory Care.” Medical Care Research and Review 60 (3 Suppl): 54S–73S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizer, S. D. , and Gardner J. A.. 2011. “Is Fragmented Financing Bad for Your Health?.” INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization Provision, and Financing 48 (2): 109–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, A. K. , Gardner J., Montez M., Loveland S., and Hendricks A.. 2005. “Dual‐System Use: Are there Implications for Risk Adjustment and Quality Assessment?” American Journal of Medical Quality 20 (4): 182–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, J. L. , and Marcantonio E. R.. 2011. “Postoperative Delirium: Acute Change with Long‐Term Implications.” Anesthesia and Analgesia 112 (5): 1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessums, L. L. , McHugh S. J., and Rajkumar R.. 2016. “Medicare's Vision for Advanced Primary Care: New Directions for Care Delivery and Payment.” Journal of the American Medical Association 315 (24): 2665–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y. , Hendricks A., Zhang S., and Kazis L. E.. 2003. “VHA Enrollees’ Health Care Coverage and Use of Care.” Medical Care Research and Review 60 (2): 253–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarlov, E. , Lee T. A., Weichle T. W., Durazo‐Arvizu R., Zhang Q., Perrin R., Bentrem D., and Hynes D. M.. 2012. “Reduced Overall and Event‐Free Survival among Colon Cancer Patients Using Dual System Care.” Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers 21 (12): 2231–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor Jr, D. H. , Østbye T., Langa K. M., Weir D., and Plassman B. L.. 2009. “The Accuracy of Medicare Claims as an Epidemiological Tool: The Case of Dementia Revisited.” Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 17 (4): 807–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe, J. M. , Thorpe C. T., Gellad W. F., Good C. B., Hanlon J. T., Mor M. K., Pleis J. R., Schleiden L. J., and Van Houtven C. H.. 2017. “Dual Health Care System Use and High‐Risk Prescribing in Patients with DementiaA National Cohort Study Dual Health Care System Use and High‐Risk Prescribing.” Annals of Internal Medicine 166 (3): 157–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, A. N. , Grebla R. C., Jiang L., Yoon J., Mor V., and Kizer K. W.. 2012. “Duplicate Federal Payments for Dual Enrollees in Medicare Advantage Plans and the Veterans Affairs Health Care System.” Journal of the American Medical Association 308 (1): 67–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, C.‐L. , Greenberg J. D., Helmer D., Rajan M., Tiwari A., Miller D., Crystal S., Hawley G., and Pogach L.. 2004. “Dual‐System Utilization Affects Regional Variation in Prevention Quality Indicators: The Case of Amputations among Veterans with Diabetes.” American Journal of Managed Care 10 (11 Pt 2): 886–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs . 2014. “172VA10P2: VHA Corporate Data Warehouse – VA. 79 FR 4377.”

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs . 2015. “System of Records Notice 97VA10P1: Consolidated Data Information System‐VA. 76 FR 25409.”

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs . 2016. “VHA Directive 1153: Access to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and United States Renal Data System (USRDS) Data for Veterans Health Administration (VHA) users within the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Information Technology (IT) Systems.”

- U.S. General Accounting Office . 1994. “Veterans health care: Use of VA services by Medicare‐eligible veterans” [accessed on December 2, 2017]. Available at http://www.gao.gov/assets/230/220386.pdf

- Veterans Health Administration . 2013. “Projections of the Prevalence and Incidence of Dementias Including Alzheimer's Disease for the Total Veteran, Enrolled and Patient Populations Age 65 and Older.”

- Wagner, T. H. , Chen S., and Barnett P. G.. 2003. “Using average cost methods to estimate encounter‐level costs for medical‐surgical stays in the VA.” Medical Care Research and Review 60 (3 Suppl): 15S–36S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, W. B. , Bott D. M., Rebecca P., and Wright S. M.. 2005. “Veterans Health Administration and Medicare Outpatient Health Care Utilization by Older Rural and Urban New England Veterans.” The Journal of Rural Health 21 (2): 167–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, S. M. , Petersen L. A., Lamkin R. P., and Daley J.. 1999. “Increasing Use of Medicare Services by Veterans with Acute Myocardial Infarction.” Medical Care 37 (6): 529–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J. , Scott J. Y., Phibbs C. S., and Wagner T. H.. 2011. “Recent Trends in Veterans Affairs Chronic Condition Spending.” Population Health Management 14 (6): 293–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W. , Ravelo A., Wagner T. H., Phibbs C. S., Bhandari A., Chen S., and Barnett P. G.. 2003a. “Prevalence and Costs of Chronic Conditions in the VA Health Care System.” Medical Care Research and Review 60 (3 Suppl): 146S–67S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W. , Wagner T. H., Chen S., and Barnett P. G.. 2003b. “Average Cost of VA Rehabilitation, Mental Health, and Long‐Term Hospital Stays.” Medical Care Research and Review 60 (3 Suppl): 40S–53S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Table S1: List of ICD‐9 Codes for Comorbidities.

Table S2: Descriptive Statistics for Market Characteristics.

Table S3: Descriptive Statistics for Priority Group and Comorbidities among Veterans Age 65 and Older Who Used Veteran Health Administration (VHA) by VHA or Combined VHA and Medicare Recorded Dementia in FY 2013.

Table S4: Association of Dementia with Cost to Veteran Health Administration (VHA), Medicare or Combined among Veterans Age 65 and Older Who Used VHA By Using VHA Data alone or Combined VHA and Medicare Data in FY 2013 (GEE Model).

Table S5: Expected Costs per Veteran per Year Based on Recycled Prediction (Estimate/95% CI).

Table S6: Sensitivity Analysis – Attributable Cost of Dementia among Veterans Age 65 and Older Who Used Veteran Health Administration (VHA) Using VHA Data Alone or Combined VHA and Medicare Data in FY 2013.

Table S7: Descriptive Statistics for Characteristics among Veterans Age 65 and Older Who Used Veteran Health Administration (VHA) by VHA Only, Medicare only, and both VHA and Medicare Reported Dementia using combined VHA and Medicare data in FY 2013.