Gender balance is an important issue for Neuropsychopharmacology (NPP) and the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ACNP), the organization that NPP represents. There is increasing awareness of the percentages of men and women represented in science faculty, academic organizations, and publication and editorial processes. This topic generates great passion and, as is often the case with complex issues, it is multifactorial in both cause and effect.

Gender balance in NPP function has not been previously explored in any depth. It is critical for to us to understand where we have been, where we are, and where our trajectory seems headed. To begin addressing these questions, we undertook a data-driven approach to characterize representation of men and women in journal function, defined here as processes in which editors, reviewers, and authors are engaged. Our foremost goal is to identify and address areas of imbalance with interventions to improve inclusivity while maximizing fairness. As an example, while it may be tempting to assume that there should currently be 50–50 gender representation in all aspects of journal function, developing policies to enforce such a balance without a broader understanding of gender demographics within our field (a hybrid mixture of disciplines including psychiatry, pharmacology, neurobiology, and others) might have unintended consequences that do more harm than good. The Senior Editors recognize the potential for unfairness in expecting the same amount of a work product (e.g., reviews) from an underrepresented group as would be expected from a group with more individuals. That expectation, even if well-intentioned, would lead to a “taxing” (over-burdening) of individuals in the smaller group and create the type of indicators (e.g., declined invitations, late reviews, low quality, or rushed reviews) that tend to work against success-related metrics required for advancement at NPP (and, in turn, the ACNP). We describe here our early findings: many NPP metrics are encouraging, especially when viewed over time, but there are areas where improvements are needed.

Methods and qualifiers

Detailed data sets reflecting reviewer demographics for NPP manuscripts became available starting in 2011, so this served as our earliest time point for analysis. For comparisons across full years, we examined 2011–2017. There was a transition to the present team of Senior Editors within this timeframe (in 2013). Some of the metrics we wanted to examine could not be reconstructed from historical (full-year) data sets, so special record keeping was enacted to enable analysis of more recent data (partial year). The interests and expertise of ACNP members are varied, and detailed demographics are not available for some subspecialties. Using the guiding principle that virtually any information we could glean regarding gender balance would be a valuable starting point, in the absence of demographics for all subspecialties, we used neuroscience demographics as a proxy. Recent estimates indicate that women represent 39% of tenure-track faculty in neuroscience [https://biaswatchneuro.com/base-rates/neuroscience-base-rates], so we used this value for base-rate comparisons. We considered tenure-track faculty as a criterion because NPP targets faculty-level researchers (rather than trainees) as reviewers and Editorial Board Members. To maintain the feasibility of this initial project, we considered data for Corresponding Authors only. Concerted efforts—including detailed on-line searches for the use of gender-specific pronouns on websites and/or photographs—were made to match an individual’s given (first) name to their gender, as recommended [https://biaswatchneuro.com/base-rates/base-rate-calculation/]. We used the terms “Grouped as Men” and “Grouped as Women”—meaning that individuals were placed into one of these groups on the basis of the information available to us at the time—to acknowledge the possibility of inaccuracies despite our best efforts. Although our goal was to identify and describe qualitative (macro) trends, we ran routine statistics (e.g., ANOVAs, t-tests, Chi-square tests) on all data as appropriate, and report statistically significant differences in the text.

Editorial roles

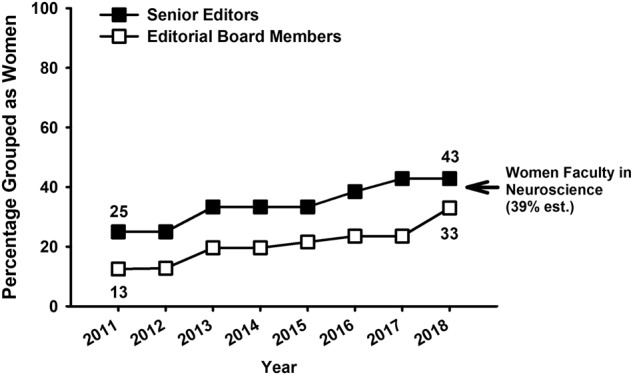

Senior Editors are responsible for managing, obtaining, evaluating, and disseminating research findings. In 2018, 43% are women (6/14) (Fig. 1a), whereas in 2011, 25% (3/12) were women. For the purposes of these calculations, the Editor-in-Chief (EIC) was grouped as a Senior Editor, but it is important to note that there has not yet been a woman EIC (journal launched in 1987). The Editorial Board is a collection of individuals who are considered (by the Senior Editors) to be leaders in the field and have a sustained track record of outstanding service to the journal, with respect to their scientific contributions or excellence (responsiveness, volume, timeliness, constructiveness) in their reviews. In 2018, 33% of Editorial Board Members (17/51) are women. In 2011, by comparison, 12.5% (6/48) were women (Fig. 1b). Balance in both of these metrics has improved appreciably over the 7-year span examined for this project.

Fig. 1.

Editorial roles in NPP from 2011 through 2017. The year 2011 is the first year for which detailed data sets became available. Percentage of women serving as Senior Editors (filled squares) and on the Editorial Board (open squares) by year

Reviewers

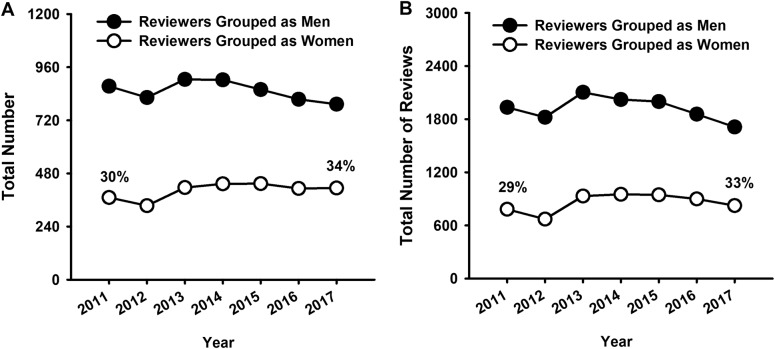

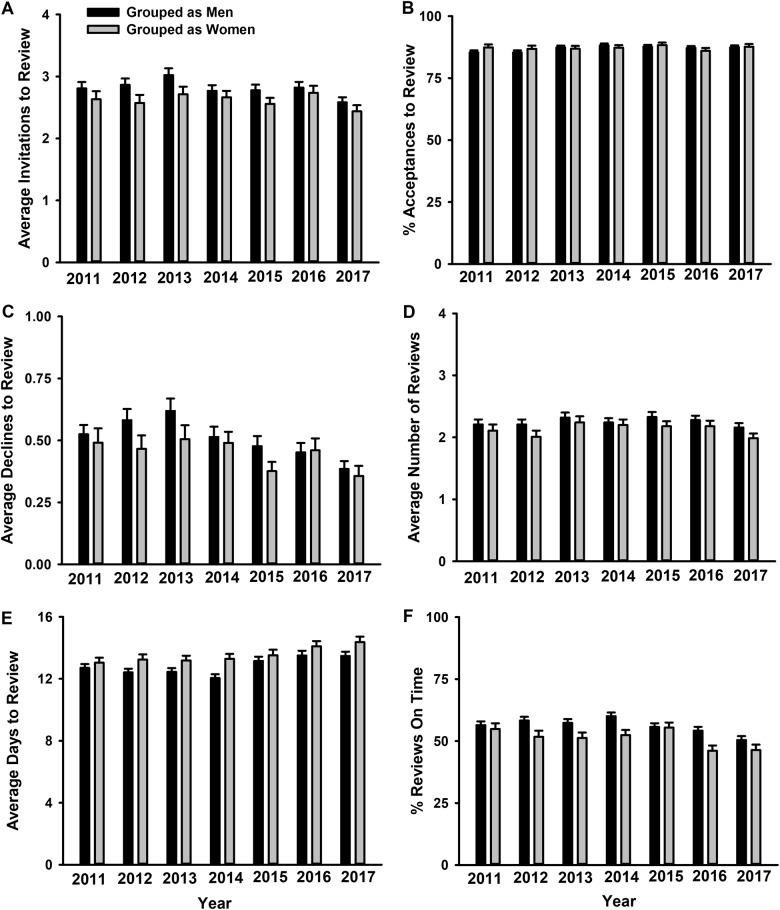

By the end of 2017, the total number of women serving as reviewers and the total number of reviews completed by women increased nominally, to 34 and 33% respectively, compared to 30 and 29% in 2011 (Fig. 2a, b). At the same time, the overall numbers of reviewers and reviews decreased slightly—thereby making similar numbers reflect higher percentages—due in part increases in the number of manuscripts rejected without review. These values align with the gender balance percentages seen in the Editorial Board, suggesting a degree of correspondence between reviewer participation and appointment to this group. While there are more men in the reviewer pool (Fig. 2a), the average number of invitations to review per reviewer (Fig. 3a), the average number of acceptances to review (Fig. 3b), and the average number of declines to review (Fig. 3c) show balance and stability over time, with no statistically significant gender differences. Likewise, the average number of reviews completed are similar and stable (Fig. 3d), with no statistically significant differences, indicating that the average woman reviewer is not burdened by NPP reviewer duties any more than the average man reviewer. Women take longer to review (Fig. 3e) and submit fewer reviews on time (Fig. 3f). While the differences between genders are statistically significant by ANOVA and post hoc tests at several time points, their sizes are small (Cohen’s d = 0.04–0.18). For example, in 2012 women took significantly more days to review and completed fewer reviews on time than men (P’s < 0.05), but the actual values are 13.2 vs. 12.4 days to review and 52 vs. 58% reviews on time, respectively. The statistical significance of these differences may speak more to the large sample sizes, imbalance in group sizes, and/or low variability rather than their meaningfulness.

Fig. 2.

Reviewers from 2011 through 2017. The year 2011 is the first year for which detailed data sets became available. a Total number of reviewers grouped as men (filled circles) or women (open circles). b Total number of reviews completed by reviewers grouped as men or women

Fig. 3.

Reviewer metrics from 2011 through 2017. The year 2011 is the first year for which detailed data sets became available. a Average number of invitations to review to individuals grouped as men (black bars) or women (grey bars). b Percentage of accepted invitations to review by individuals grouped as men or women. c Average declines to review by individuals grouped as men or women. d Average number of reviews completed by individuals grouped as men or women. e Average number of days to complete a review by individuals grouped as men or women. f Percentage of reviews submitted on time by individuals grouped as men or women

Authors

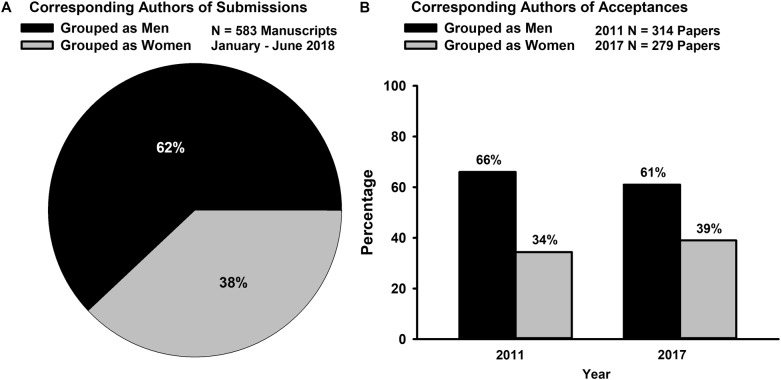

We used the most updated data possible to examine author demographics. Between January 1 and June 30 of 2018, 38% of corresponding authors of the 583 submitted manuscripts to NPP were women (Fig. 4a). (Note that many of these 583 manuscripts are still under consideration, precluding analysis of acceptance rates and making this a partial year analysis.) In 2017, the most recent full year for which all decisions have been rendered, 39% of accepted papers had women as corresponding authors (Fig. 4b). Both of these values align with the estimate (39%) of women faculty in the field, but considering that authors are often trainees, they fall short of the blended estimate for women faculty and trainees (45% in neuroscience). Gender balance among corresponding authors improved nominally compared to 2011, when 34% percent of corresponding authors of accepted manuscripts were women. Considering the similarities in proportions for both metrics, it seems unlikely that the gender of the corresponding author influences manuscript outcome. Nonetheless, we will continue to monitor submissions and acceptances throughout 2018 and report on these data in early 2019.

Fig. 4.

Corresponding authors of submitted and accepted manuscripts. a Percentage of men (black segment) and women (grey segment) submitting to NPP as corresponding authors from January 1 through June 30, 2018 (these data required special record-keeping, so earlier data are not available). b Percentage of men (black bars) and women (grey bars) who were corresponding authors of accepted manuscripts in NPP in 2011 vs. 2017

Representation

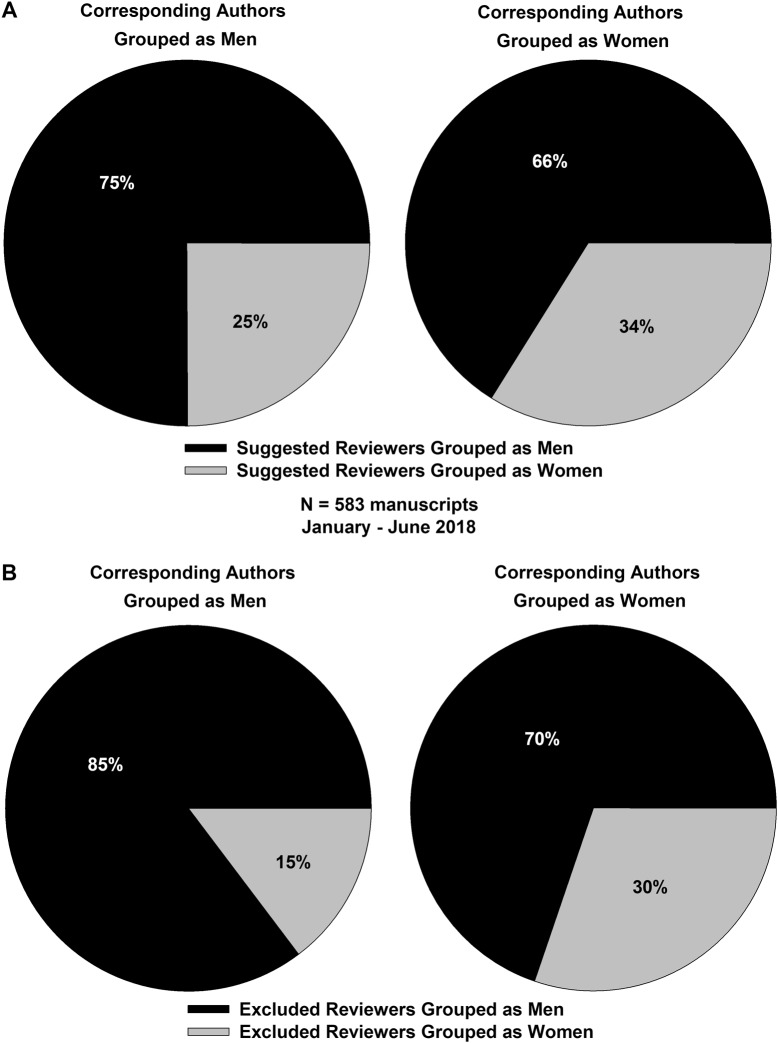

We sought additional insight on why representation of women on the Editorial Board lags further behind representation of men than it does in other metrics. Individuals are appointed to the NPP Editorial Board based on service as reviewers, as indicated by objective, data-driven metrics including number of manuscripts reviewed, days to complete reviews, and percentage of accepted invitations to review. Historically, the NPP Senior Editor team has prioritized these metrics because they reflect elements of efficiency in journal function that may enhance our ability to attract high-impact research reports, which was revealed via a recent survey as the highest priority for the ACNP membership. As such, any journal processes that tend to favor male reviewers—even if unintentionally—may have a by-product of leading to more men than women on the Editorial Board. We now have a better understanding of how both editors and authors make critical contributions to some of these processes. When authors submit a manuscript, they are prompted to list “Suggested Reviewers” and “Reviewers to Exclude”. At NPP, Senior Editors are empowered to use these suggestions when assembling a team of reviewers. (We recognize that this is not true for all journals.) Because we frequently consider author suggestions in the review process, gender imbalance within the cohorts of suggested reviewers provided to us by the authors could be an important contributor to gender imbalance in reviewer demographics, which in turn leads to gender imbalance in representation on the Editorial Board.

To determine if author-initiated suggestions could be a source of gender imbalance in reviewers, we began examining patterns of author suggestions for all manuscripts submitted over the period of January 1–June 30, 2018. This required special record-keeping, so earlier data are not available. These data clearly show that both men and women more frequently suggest (and exclude) reviewers who are men (P’s < 0.01) (Fig. 5a, b), although women corresponding authors are slightly more likely to suggest women as reviewers (P < 0.01). These findings may indicate that both genders recognize that the reviewer pool has more men and make suggestions that resemble the qualitative demographics of the field. It is important to emphasize, however, that the instructions on the submission portal simply direct authors to “list the names of 6 reviewers who are knowledgeable in [the] area and could give an unbiased review of [the] work”, with no mention of other qualifying factors, leaving the process open to the interpretation—and potential implicit biases—of the corresponding authors who are making the suggestions. Regardless of the explanation for why both men and women list more men as reviewers in our open-ended suggestion system, the fact that it occurs in this way would be expected to lead to exactly the imbalance we currently face: more men than women serving as reviewers, and thus more men than women serving on the Editorial Board.

Fig. 5.

Reviewers suggested to include or exclude by corresponding author group between January 1 and June 30, 2018. These data required special record-keeping, so earlier data are not available. a Left; percentage of suggested reviewers grouped as men (black segment) and women (grey segment) by corresponding authors grouped as men. a Right; percentage of suggested reviewers grouped as men and women by corresponding authors grouped as women. b Left; percentage of excluded reviewers grouped as men and women by corresponding authors grouped as men; b Right; percentage of excluded reviewers grouped as men and women by corresponding authors grouped as women

Path forward

As of July 1, 2018, we have taken three explicit steps to improve reviewer balance. First, the EIC (WC) sent a written reminder to Senior Editors to more carefully consider gender balance when making reviewer assignment. Second, NPP has added more detailed instructions to the on-line submission platform to encourage authors to be more mindful of the suggestions they make, while being careful to not promote an impression that the Senior Editors want to receive anything other than the list that the authors want to provide: “NPP Editors wish to enhance diversity in all journal functions, including the composition of our reviewer pool, and emphasize that this is an opportunity for authors to participate in this process”. Third, we have released some of the data described above on NPP social media accounts to broadly promote mindfulness and stimulate discussion among our readership active in this domain. We believe that if implicit bias is contributing to gender imbalances in journal function, then stimulating awareness of areas where it is especially likely to occur may reduce its impact.

We plan to continue to collect data on author suggestions for the period of July 1–December 31, 2018, to determine if these initial interventions are effective in improving the balance in suggested reviewers, before considering other potential options. One option would be to impose strict policies for gender balance in reviews. A concern is that enforcing this type of policy will invariably lead to longer review processes, because reviews would not proceed to their conclusion until the proper gender balance in reviewers was achieved. Protracted reviews are broadly unpopular among authors regardless of gender, especially considering that timely reviews can often play an important part in receiving grants and promotions. Early findings will be discussed at the ACNP annual meeting in December 2018 and the final data set will be released early in 2019. We want to minimize creation of burdens on faculty from underrepresented groups, but recognize that optimizing balance is a critical element of being type of journal that NPP aspires to be.

While in retrospect we wish we had begun our efforts to improve gender balance in journal function sooner, we are encouraged that the journal appears strong in numerous domains, with many metrics resembling estimates of gender balance in key NPP (and ACNP)-related fields. We have identified areas (e.g., gender balance on our Editorial Board) where improvements are needed, and implemented plans to mitigate areas of imbalance and to report on progress within the near future. Finally, we acknowledge that gender is only one demographic of which we need to be more mindful when considering balance in journal function. These are issues that will require teamwork and cooperation from our entire community to solve.

Acknowledgements

The concept for this article was proposed to the NPP Senior Editors by CJJ, who completed the project as part of an Editorial Internship. We thank NPP staff members Terri Bowen, Ania Bukowski, Lori Kunath, and Jennifer Mahar for providing the data in formats that would not reveal privileged information regarding manuscript decisions, and NPP Social Media Editor Gretchen Neigh for disseminating our early findings on journal accounts.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.