Abstract

The total number of acquired melanocytic nevi on the skin is strongly correlated with melanoma risk. Here we report a meta-analysis of 11 nevus GWAS from Australia, Netherlands, UK, and USA comprising 52,506 individuals. We confirm known loci including MTAP, PLA2G6, and IRF4, and detect novel SNPs in KITLG and a region of 9q32. In a bivariate analysis combining the nevus results with a recent melanoma GWAS meta-analysis (12,874 cases, 23,203 controls), SNPs near GPRC5A, CYP1B1, PPARGC1B, HDAC4, FAM208B, DOCK8, and SYNE2 reached global significance, and other loci, including MIR146A and OBFC1, reached a suggestive level. Overall, we conclude that most nevus genes affect melanoma risk (KITLG an exception), while many melanoma risk loci do not alter nevus count. For example, variants in TERC and OBFC1 affect both traits, but other telomere length maintenance genes seem to affect melanoma risk only. Our findings implicate multiple pathways in nevogenesis.

Melanocytic nevus count is associated with melanoma risk. In this study, a meta-analysis of 11 nevus GWAS studies identifies novel SNPs in KITLG and 9q32, and bivariate analysis with melanoma GWAS meta-analysis reveals that most nevus genes affect melanoma risk, while melanoma risk loci do not alter the nevus count.

Introduction

The incidence of cutaneous malignant melanoma (CM) has increased in populations of European descent in North America, Europe, and Australia due to long-term changes in sun exposure behavior, as well as screening1. The strongest CM epidemiological risk factor acting within populations of European descent is the number of cutaneous acquired melanocytic nevi, with risk increasing by 2–4% per additional nevus counted2. Nevi are benign melanocytic tumors usually characterized by a signature somatic BRAF mutation. Their association with CM can be direct, in that a proportion of melanomas arise within a pre-existing nevus (due to a “second hit” mutation), or indirect, where genetic or environmental risk factors for both traits are shared. Total nevus count is highly heritable (60%–90% in twins)3,4, but only a small proportion of this genetic variance is explained by loci identified so far5–9. The known nevus count loci all have pleiotropic effects on CM risk5–9, which implies both that nevus count loci are medically important and that a genetic analysis combining nevi and CM phenotypes will have increased statistical power. Here we present a new large nevus genome-wide association meta-analysis, and combine these results with those of a previously published meta-analysis of melanoma10.

Results

Nevus GWAS meta-analysis

Genome-wide single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotype data were available for a total of 52,806 individuals from 11 studies in Australia, UK, USA, and the Netherlands (Table 1), where nevus number had been measured by counting or ratings, by self or observer, and of the whole body or selected regions. Analyses show that these are measuring the same entity and are therefore combinable for GWAS (genome-wide association study; see Supplementary Results). The genomic inflation factors were λ = 1.41 and λ1000 = 1.008 (Q–Q plot, Supplementary Fig. 1), consistent with polygenic inheritance and the total sample size.11 Five genomic regions contained association peaks that reached genome-wide significance in the nevus count meta-analysis (Fig. 1, Table 2, Supplementary Fig. 2), MTAP/CDKN2A on chromosomes 9p21.3 (peak SNP, P = 2 × 10−37) and 9q31.1-2 (P = 1 × 10−8), IRF4 on chromosome 6p (peak SNP, P = 4 × 10−37), in KITLG in the region of the known testicular germ cell cancer risk locus (P = 8 × 10−9), rs600951 over DOCK8 on chromosome 9p24.3 (P = 2 × 10−8), and PLA2G6 on chromosome 22 (P = 3 × 10−18). We have previously detected three of these in analyses using subsets of the meta-analysis sample5,10. A SNP, rs251464, in PPARGC1B (P = 5 × 10−7), reached a suggestive level of association. We detected statistical heterogeneity in association with nevus count especially for IRF4, MTAP, PLA2G6, and DOCK8 (see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2)—that for IRF4 was expected—given our original studies of this gene showing crossover G × age interaction.10 Meta-regression including age of the current study participants confirmed the age effect in the case of IRF4 (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

GWAS studies of nevus count contributing to the present meta-analysis

| Study | Nevus assessment | SNP chip | Imputation | Individuals (families) | Age range (mean) | Location (center) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALSPAC39 | Self-count on limbs | 550k | 1000Gv.3 | 3309 | 14–17 (15.5) | UK (Bristol) |

| Harvard8 | Self-count >3 mm on limbs | Affy+Illumina various | 1000Gv.3 | 32,975 | 35–75 (52) | US (Boston) |

| Leeds40 | Whole-body count >2 mm | OmniExpressExome | HRC v.1 | 397 | 21–80 (57) | Yorkshire |

| QIMR BTNS children3 | Whole-body count >0 mm | 610k, CoreExome | 1000Gv.3 | 3261 (1309) | 9–23 (12.6) | SE Queensland (Brisbane) |

| QIMR BTNS parents9 | Self-rating 4-point scale | 610k+CoreExome | 1000Gv.3 | 2248 (1299) | 29–72 (44.1) | SE Queensland |

| QIMR adult twins41 | Self-rating 4-point scale | 317k+370k+610k+CE | 1000Gv.3 | 1848 (1113) | 29-–79 (52.3) | Australia wide |

| QIMR >50 twins42 | Self-count right arm >4 mm | 370k+610k+CE | 1000Gv.3 | 893 (596) | 50–92 (60.7) | Australia wide |

| Raine43 | Nurse-count right arm | 660k | 1000Gv.3 | 808 | 22 | Western Australia (Perth) |

| Rotterdam44 | Whole-body rating 4-pt scale | 550k, 610k | 1000Gv.3 | 3319 | 51–98 (67) | Rotterdam (NL) |

| TEST45 | Whole-body count >0 mm | 610k+CE | 1000Gv.3 | 136 (71) | 5–18 (9.7) | Tasmania+Victoria |

| Twins UK5 | Whole-body count >2 mm | 317k+610k+1M+1.2M | 1000Gv.3 | 3312 (1839) | 18–80 (47) | UK wide (London) |

| Total nevus | 52,506 | |||||

| Melanoma GWASMA10 | 12,874 cases; 23,203 controls | |||||

| Nevus+melanoma | 88,583 (inc. controls) |

Fig. 1.

Miami plot of nevus count and melanoma meta-analysis. P values where either P < 10−5. The –log10 P values for the nevus GWAS meta-analysis are above the central solid line and those for the melanoma GWAS meta-analysis are below that line. Novel nevus loci are highlighted

Table 2.

SNPs associated with total nevus count and cutaneous melanoma (CM) in their respective meta-analyses

| SNP | Position (hg19) | Combined P | CM P | Nevus P | Gene/interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs869329 | 9:21804693 | 7.48E−67 | 1.14E−31 | 2.12E−37* | MTAP |

| rs11532907 | 9:21844772 | 1.72E−34 | 1.42E−19 | 2.30E−17 | |

| rs132985 | 22:38563471 | 2.07E−28 | 4.76E−12 | 3.06E−18* | PLA2G6 |

| rs2005974 | 22:38537112 | 3.30E−23 | 7.83E−11 | 3.31E−14 | |

| rs12203592 | 6:396321 | 5.84E−01 | 8.22E−01 | 4.21E−67* | IRF4 |

| rs7313352 | 12:88949124 | 2.27E−05 | 6.61E−01 | 8.40E−09 | KITLG** |

| rs600951 | 9:224742 | 9.89E−13 | 5.52E−06 | 1.95E−08* | DOCK8** |

| rs10816595 | 9:110709735 | 1.70E−14 | 1.49E−07 | 1.08E−08 | 9q31.2 |

| rs251464 | 5:149196234 | 1.92E−09 | 4.58E−04 | 4.71E−07 | PPARGC1B |

| rs4670813 | 2:38317710 | 1.14E−10 | 2.40E−05 | 5.70E−07 | CYP1B1 |

| rs1640875 | 12:13069524 | 3.30E−11 | 4.08E−07 | 5.72E−06* | GPRC5A** |

| rs1148732 | 12:13068291 | 1.08E−09 | 2.08E−04 | 6.21E−07 | |

| rs55875066 | 2:240076002 | 1.35E−09 | 2.16E−04 | 7.59E−07 | HDAC4** |

| rs12696304 | 3:169481271 | 8.30E−10 | 1.64E−05 | 5.73E−06 | TERC |

| rs117648907 | 15:33277710 | 1.13E−10 | 1.43E−06 | 6.52E−06 | FMN1** |

| rs45575338 | 10:5784151 | 2.16E−08 | 2.87E−04 | 1.02E−05 | FAM208B** |

| rs1484375 | 9:109067561 | 1.56E−10 | 2.30E−08 | 1.35E−04 | 9q31.1 |

| rs2357176 | 14:64409313 | 3.89E−08 | 1.74E−05 | 1.95E−04 | SYNE2** |

| rs34466956 | 19:3353622 | 2.92E−08 | 1.02E−05 | 2.22E−04 | NFIC** |

| rs1636744 | 7:16984280 | 1.29E−09 | 1.84E−09 | 0.002 | TCONS_l2_00025686 |

| rs380286 | 5:1320247 | 3.18E−14 | 1.66E−17 | 0.003* | TERT |

| rs2695237 | 1:226603635 | 1.49E−11 | 3.59E−13 | 0.004 | PARP1 |

| rs73008229 | 11:108187689 | 8.21E−11 | 1.38E−12 | 0.006 | ATM |

| rs72704658 | 1:150833010 | 1.90E−10 | 3.88E−12 | 0.007 | SETDB1 |

| rs12596638 | 16:54115829 | 2.30E−08 | 1.81E−09 | 0.014 | FTO |

| rs416981 | 21:42745414 | 3.90E−10 | 3.28E−15 | 0.063 | MX2 |

| rs75570604 | 16:89846677 | 1.64E−45 | 6.24E−92 | 0.067 | MC1R |

| rs7582362 | 2:202176294 | 4.32E−06 | 8.88E−09 | 0.134 | CASP8 |

| rs498136 | 11:69367118 | 1.42E−06 | 1.01E−10 | 0.209 | TPCN2/CCND1 |

| rs56238684 | 20:33236696 | 5.14E−13 | 8.36E−25 | 0.215 | ASIP |

| rs2125570 | 6:21166705 | 9.14E−05 | 3.27E−08 | 0.351 | CDKAL1 |

| rs184628474 | 14:91185865 | 4.32E−07 | 4.63E−14 | 0.415 | TTC7B |

| rs10830253 | 11:89028043 | 2.32E−11 | 1.01E−26 | 0.605 | TYR |

| rs250417 | 5:33952378 | 5.18E−05 | 2.30E−12 | 0.755 | SLC45A2 |

| rs4778138 | 15:28335820 | 5.52E−03 | 3.11E−09 | 0.935 | OCA2 |

The weighted Stouffer method was used to combine the nevus and melanoma P values (Combined P). The SNP with the smallest combined P value under each peak is shown, but the table rows are ordered by strength of association to nevus count. In three cases where significant between-study heterogeneity is detected (unadjusted Phom < 0.05, denoted by *), the nevus P value is from the random-effects model of Han and Eskin38, and a result for a nearby SNP where Phom > 0.05 is included on the line beneath (italicized) to confirm genome-wide significance (in the case of IRF4 and DOCK8, there is no such nearby SNP).

*Unadjusted Phom < 0.05

**Novel loci

Combining nevus and melanoma GWAS meta-analyses—Bayesian analysis

We then combined these nevus meta-analysis P values with those from the melanoma meta-analysis10 (Table 1, Fig. 2, Supplementary Figs 1, 2). We used simple combination of P values (weighted Stouffer method), as well as the GWAS-PW program,12 which combines GWAS data for two related traits to investigate the causes of genetic covariation between them (see Supplementary Methods). Specifically, it estimates Bayes factors and posterior probabilities of association (PPA) for four hypotheses: (a) a locus specifically affects melanoma only or (b) affects nevus count only; (c) a locus has pleiotropic effects on both traits; and (d) there are separate alleles at a locus independently determining each trait (colocation).

Fig. 2.

Manhattan plot of P values from meta-analysis combining nevus and melanoma results

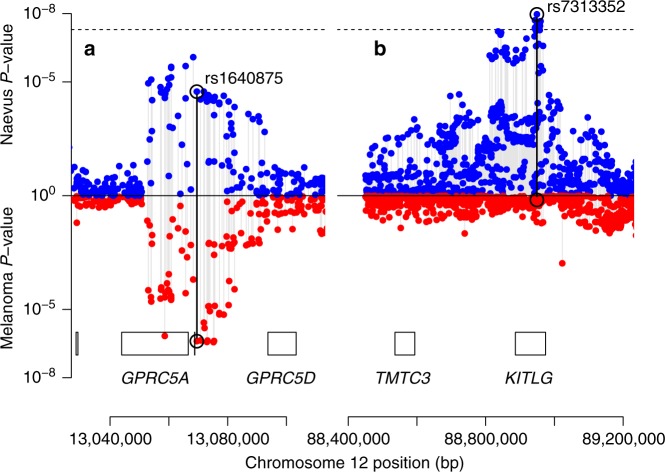

There were 30 regions containing SNPs that met our threshold for “interesting” (PPA > 0.5) for any of these hypotheses (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 3). Twelve of these loci exhibited no evidence of association to nevus count, but were strongly associated with melanoma risk, one of the most extreme being MC1R. A total of 18 loci showed pleiotropic action with consistent directional and proportional effects of all SNPs on nevi and melanoma risk, the strongest being MTAP, PLA2G6, and an intergenic region on 9q31.1 (Fig. 4a shows a bivariate regional association around GPRC5A, all loci are shown in Supplementary Figs 5–19). There were no “pure nevus” regions using the binned GWAS-PW test (hypothesis b, PPAb > 0.2), with even the region of KITLG appearing as a pleiotropic region (PPAb = 0.52, PPAc = 0.11), even though the pattern of bivariate association appears more consistent with a “nevus-only” locus (Fig. 4b). For another five regions, support was split between the pure melanoma and pleotropic models. In the case of IRF4, this is certainly driven by the marked between-study heterogeneity in melanoma association due to their different age distributions and latitudinal origins13.

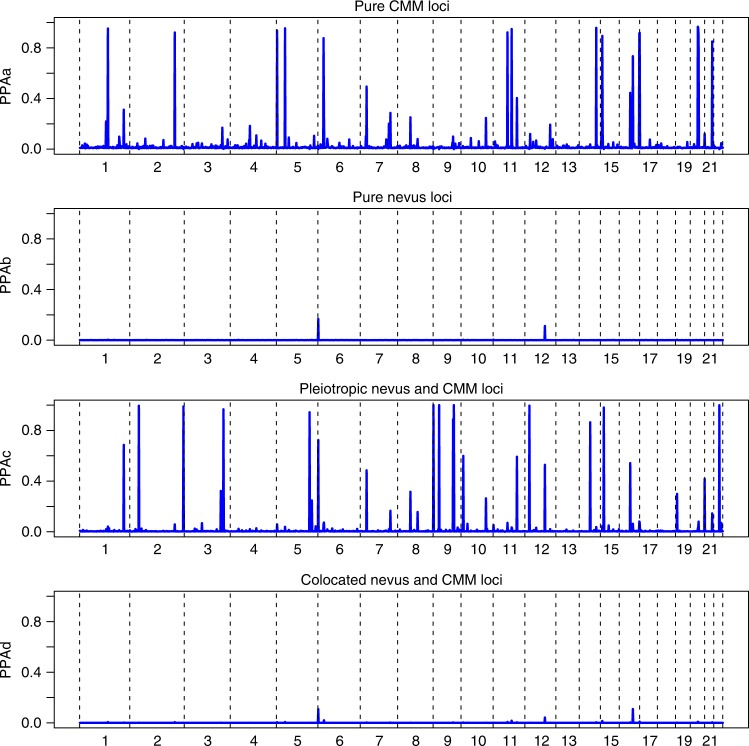

Fig. 3.

Results of analyses using GWAS-PW, which assign posterior probabilities (PPA) to each of ~ 1700 genomic regions that is a a pure melanoma locus, b a pure nevus locus, c a pleiotropic nevus and melanoma loci, and d that the locus contains co-located but distinct variants for nevi and melanoma

Fig. 4.

Plot of nevus and melanoma association test P values for a the region around rs1640875 in GPRC5A (chr12:12.9 Mbp) illustrating symmetrical influence on nevus count and melanoma risk; note that neither univariate peaks achieve significance alone but in combination they do (see Table 2, Fig. 2), and b the region around rs7313352 in KITLG (chr12:88.6 Mbp), a “pure” nevus locus with negligible direct effect on melanoma risk

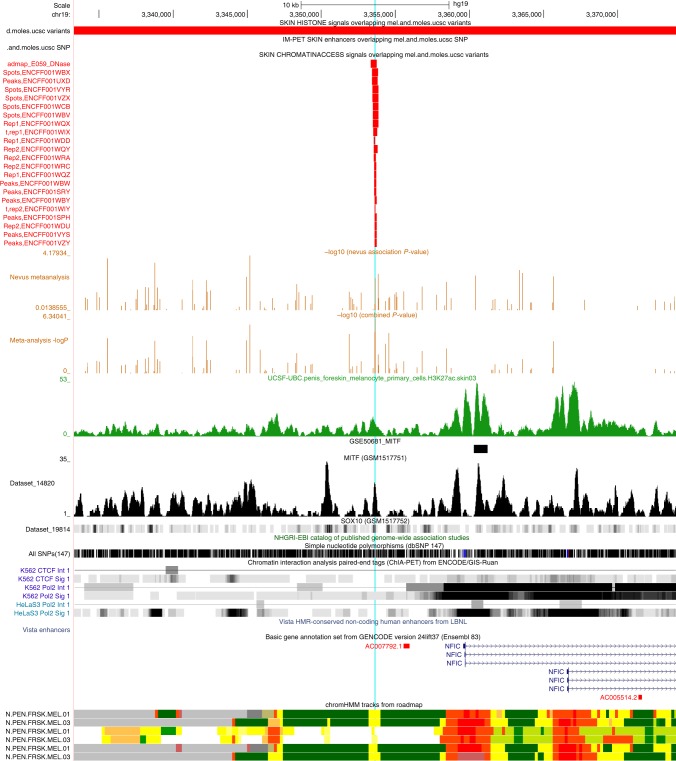

One interesting SNP (rs34466956), 2 kbp upstream from NFIC on chromosome 19p13.3 (see Fig. 5), achieved a combined P value of 3 × 10−8 and a SNP-wise PPAc for pleiotropism of 0.9, even though the binned GWAS-PW assigned the region a highest PPA of 0.28.

Fig. 5.

UCSC Genome Browser view of region near NFIC (19p13.3). The pale blue line highlights location of rs34466956, which coincides with a narrow regulatory region as seen in in the 22 short red bars indicating open chromatin in melanocytes and skin. These align in the bottom 6 tracks with narrow yellow regions indicating results of hidden Markov models summarizing the evidence from multiple experiments for open chromatin in melanocytes. An MITF ChipSeq peak also overlies this same region (gray track, GSM1517751). NFIC is expressed in melanocytes, and a second larger MITF peak overlies intron 1 in two ChipSeq experiments viz. GSE50681_MITF, see short solid black bar, and also the tall sharp gray peak below it in GSM1517751. See Supplementary Methods for details

Pleiotropy

The 18 pleiotropic loci each come from multiple pathways, indicating that nevogenesis is a more complicated process than previously anticipated. Pathways already implicated include those of MTAP (purine salvage pathway, possibly a rate limiting step to cell proliferation), PLA2G6 (phospholipase A2, implicated in apoptosis), and IRF4 (melanocyte pigmentation and proliferation). Newly implicated here in nevogenesis, TERC is a strong candidate given its involvement in telomere maintenance and prior suggestive evidence of association with melanoma/nevi10,14,15, as well as several other cancers.16–18 PPARGC1B has previously been investigated as a skin color locus17 and there is functional evidence for its effects on melanocytes.18 GPRC5A (see Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 15) has also been suggestively associated with melanoma10 and is a known oncogene in breast and lung cancer19,20. DOCK8 deficiency predisposes to virus-related malignancy and is deleted in some cancers, but not markedly in melanoma.21,22 DOCK8 regulates Cdc42 activation especially in immune effector cells—Cdc42 has been implicated in melanoma invasiveness23 and variants in CDC42 have been previously associated with melanoma tumor thickness24 —though our best association P value in the region of that latter gene is 3 × 10−4.

The novel pleiotropic loci are: (a) the region around HDAC4 on chromosome 2; (b) chromosome 9q31 (two separate peaks); (c) near SYNE2 on chromosome 14; (d) in DOCK8 on chromosome 9p; and (e) near FMN1 on chromosome 15p (see Supplementary Results). For those loci that unequivocally lie within a gene, in each case that gene is expressed in melanocytes25 and these implicate several different pathways. The “master regulator” in melanocytogenesis26 is MITF (microphthalmia-associated transcription factor), and we confirmed that our top candidate genes in each of the 30 regions contain MITF binding sites.27 For example, three genes in the FMN1 region harbor MITF binding sites, viz. SCG5, RYR3, and FMN1 themselves (enrichment P = 0.01). Furthermore, in several of these genes (MTAP, IRF4, PLA2G6, GPRC5A, and TERC), the most associated SNP lies within or close to the actual MITF binding sites, in some cases a rarer MITF–BRG1–SOX10–YY1 combined regulatory element (MARE)27 (Supplementary Figs 20–40).

Gene based tests

The genes most strongly implicated in a gene-based association analysis (PASCAL) are MTAP, PLA2G6, GPR5A, ASB13 (adjacent to FAM208B), and KITLG (P = 2.3 × 10−6); see Supplementary Table 4). At a suggestive level, we note FAM208B, MGC16025 (both P = 6 × 10−6), and HDAC4 (1 × 10−5). Among genes at a significance level of <10−4, we highlight LMX1B (P = 5 × 10−5), where rs7854658 gave a nevus P value of 3.3 × 10−6.

Pathway analysis

Using different approaches (GWAS PRS, GWAS-PW, and REML using SNP sets; see Supplementary Table 5), we tested candidate pathways28 for their overall contribution to variance in nevus number, the contribution of the telomere maintenance pathway was 0.8%. A contribution of the immune regulation/checkpoint pathway was surprisingly absent, given our knowledge that immunosuppression increases nevus count quite promptly and the recent success of CTLA4 inhibitors in the treatment of melanoma. We did see a weak signal (Combined P = 1 × 10−7) for rs870191, very close to SLE-associated SNPs just upstream from MIR146A, an important immune regulator.

Genetic relationships with telomere length and pigmentation

In the GWAS-PW analysis combining melanoma and telomere length (TL) (see Supplementary Methods), there was considerable locus overlap, while by contrast only TERC was detectably shared between nevus count and TL (Supplementary Fig. 41). Note that SNPs in OBFC1 were only significantly associated with melanoma in the phase 2 analysis of Law et al.10—which are not utilized in the GWAS-PW analysis—although they were suggestively associated (P = 10−5) with nevus count. In the parallel analysis with pigmentation (indexed by dark hair color), only IRF4 overlapped with nevus count (Supplementary Fig. 42). Again, multiple pigmentation loci acted as risk factors for melanoma (with no overlap with TL). The fact that only TERC (and OBFC1) are associated with nevus count, while multiple loci are associated with melanoma, is not necessarily surprising. Telomere maintenance may predispose to melanoma directly as well as via nevus count, an extension of the “divergent pathway” hypothesis for melanoma29. However, the link with telomere length-associated SNPs may need a bigger sample size to look at associations further.

SNP heritability and genetic correlation

Mixed-model twin analyses with GCTA and LDAK (see Supplementary Methods) utilizing the Australian and British samples estimate the total heritability of nevus count to be 58% (and family environment 34%), with contributions from every chromosome and one-sixth from chromosome 9 alone (see Supplementary Table 6). We found that ~25% of the Australian and ~15% of British genetic variance for nevus count could be explained by a panel of 1000 SNPs covering our 32 regions. We have also performed analyses examining the overall architecture of the relationship between nevus count and melanoma risk using bivariate LD score regression analysis and estimated rg = 0.69 (SE = 0.16) (see Supplementary Results). Alleles which increase nevus number proportionately increase the risk of melanoma (Supplementary Results, Supplementary Figs 43, 44) with KITLG, the interesting exception is that the nevus-associated variants did not predict melanoma risk (see Fig. 5b), rather, predisposing to other cancers (e.g., testicular germ cell).

Discussion

It has been long suggested that carrying out genetic analyses using multiple correlated phenotypes will increase power to detect trait loci in such a way as to justify the statistical complications. Since number of cutaneous nevus is strongly correlated with melanoma risk, and known nevus loci were associated with CM, it seemed likely that this would be a fruitful approach. We have highlighted eight novel loci, including the genes HDAC4, SYNE2, and most notably GPRC5A, where quite large samples of melanoma cases or nevus count were not sufficiently powerful to reach formal genome-wide significance in univariate analyses, but the combined evidence is conclusive.

Given that lighter skin color is also associated with both these phenotypes, we would expect a strong contribution from pigmentation pathway genes. Among those novel pleiotropic loci implicated in nevus count, CYP1B1 and PPARGC1B both appear in a recent skin pigmentation meta-analysis30 as harboring variants lightening skin color. The SNPs in the chromosome 7p21.1 region near AHR and AGR3 previously associated with CM also appear to be associated with skin color in that study. In our analysis, the signal for nevus count from that interval (best P = 3 × 10−4) was half as strong as that for CM, and the GWAS-PW analysis support was equal for the hypotheses of a pure CM locus and a pleiotropic locus (region PPAa = 0.494, PPAc = 0.485). In passing, the peak SNPs lie within a long noncoding RNA gene (TCONS_I2_00025688) that is expressed in melanocytes, so this is a potential candidate for both skin color and CM. In the case of KITLG, the variant most strongly associated with pigmentation (fair hair), rs12821256, modifies a distant enhancer, and was associated neither with melanoma or nevus count in our study (see Supplementary Results). We observe a similar pattern (association Pnevus = 0.4, PCM = 0.8) for the strongest associated variant for skin color from the skin color meta-analysis, rs11104947.30

By contrast, HDAC4 and DOCK8 are in pathways that have not been implicated as important to nevogenesis or melanoma pathogenesis. HDAC4 is involved in transcriptional regulation in many tissues, while DOCK8 acts to regulate signal transduction, most notably in immune effector cells (see Supplementary Results). The association peak for HDAC4 is quite wide (~80 kbp), and overlaps with the multi-tissue GTEx eQTL peak for this gene.31 The best overlapping SNP was rs115253975, with a combined nevus-CM P-value of 4 × 10−9 and fibroblast HDAC4 eQTL P-value of 2 × 10−5. The peak nevus-CMM DOCK8 SNP, rs600951, is a cis-eQTL in two (non-cutaneous) tissues, and the peak around it contains several eQTL SNPs detected in the GTEx skin samples. These eQTL SNPs would be potential causal candidates.

Both SYNE2 (encoding nesprin-2) and FMN1 (formin-1) are involved in nuclear envelope and cytoskeleton function, and through this in regulating as well as facilitating numerous biological pathways. Both, for example, are involved in directed cell migration. The nesprin and formin families have been implicated in efficient repair of double strand DNA breaks, so this might point to a mechanism for an association with nevi and CM (see Supplementary Results).

We did see heterogeneity between studies in strength of SNP association with nevus count or melanoma for four loci, most extremely for IRF4 (Supplementary Fig. 10). Meta-regression analysis suggested this is partly due to interactions with age in the case of IRF4 (Supplementary Table 1)—different nevus subtypes are known to predominate at different ages, with the dermoscopic globular type most common before age 20.32 We suspect sun exposure another important interacting covariate, given large differences in total nevus count by latitude.33,34

Epidemiologically, the etiology of melanoma has been divided35 into a chronic sun-exposure pathway and a nevus pathway, where intermittent sun exposure is sufficient to increase risk. At a genetic level, pigmentation genes such as MC1R contribute only via the former pathway (though this can include effects on DNA repair36), others such as MTAP via the latter, while yet others such as IRF4 seem to act via both routes13. We interpret our results as consistent with the hypothesis that nevus number is the intermediate phenotype in a causative chain to melanoma originating in all these biologically heterogeneous nevus pathways. However, we acknowledge that there may also be some genes where there is a direct causal pathway to both phenotypes.

Methods

We carried out a meta-analysis of 11 sizeable GWAS of total nevus count in populations from Australia, Netherlands, Britain, and the United States, subsets of which have been reported on previously5,6,8, and then combined these results with those from a recently published meta-analysis of melanoma GWAS10 to increase power to detect pleiotropic genes. While nevus counts or density assessments are available for melanoma cases from a number of studies, in the meta-analysis of nevus count we included only samples of healthy individuals without melanoma, all of European ancestry (for more details, see Supplementary Methods).

Nevus phenotyping

The assessment of nevus counts varies considerably between the 11 studies in four respects (see Table 1): (a) nevus counts vs. density ratings; (b) whole body vs. only certain body parts; (c) all moles (> 0 mm diameter) or only moles >2 mm, or 3 mm, or 5 mm; and (d) count by trained observer or self-count by study participant. These differences could contribute statistical heterogeneity into our analyses, so we have done considerable preliminary work to convince ourselves that all assessments are measuring the same biological dimension of “moliness” (see Supplementary Fig. 3). A pragmatic test of this is the relative contribution of each study to the detection of the known loci of large effect, which is evident from the forest plots (Supplementary Figs 5–19).

Statistical methods

Given this, we combined results from each study as regression coefficients and associated standard errors in standard fixed and random effects meta-analyses using the METAL37 and METASOFT38 programs. Manhattan and Q–Q plots for the nevus GWAS meta-analysis (GWASMA) are shown in Supplementary Fig. 45 and for each of the contributing studies in Supplementary Figs 46–55.

We combined the results from the nevus meta-analysis above with results from stage 1 of a recently published meta-analysis of CM10. Stage 1 of the CM study consisted of 11 GWAS data sets totaling 12,874 cases and 23,203 controls from Europe, Australia, and the United States; this stage included all six published CM GWAS and five unpublished ones. We do not utilize the results of stage 2 of that study, where a further 3116 CM cases and 3206 controls from three additional data sets were genotyped for the most significantly associated SNP from each region, reaching P < 10−6 in stage 1. As a result, certain melanoma association peaks are not genome-wide significant in their own right in the present bivariate analyses. Further details of these studies can be found in the Supplementary Note to Law et al.10. The combination of the nevus and melanoma results was performed using the Fisher method. A Manhattan plot for the combined nevus GWASMA plus melanoma GWASMA is shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. For more details of statistical methods, see Supplementary Methods.

Electronic supplementary material

Author contributions

S.C., J.H.B., N.K.H., S.M., A.H., M.K., D.H., J.A.N.B., T.D.S., D.M., G.D.S., T.E.N., D.T.B., V.B., M.F., J.H., and N.G.M. designed the study and obtained funding. G.Z., X.L., M.S., M.I., L.C.J., D.M.E., S.Y., J.B., M.L., P.K., A.V., J.C.T., F.L., J.A.M., and D.G. analyzed the data. M.J.W., E.N., and A.G. contributed to data collection and phenotype definitions. G.W.M., A.K.H., L.B., A.M.I., A.U., P.A.M., A.C.H., E.N., and M.B. contributed to genotyping. D.L.D. and N.G.M. wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors contributed to the final version of the paper.

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the authors upon application.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jiali Han and Nicholas G. Martin.

Full list of members of the Melanoma GWAS Consortium is given at the end of this paper.

Change history

1/14/2019

The original version of this Article contained errors in the spelling of the authors Fan Liu and M. Arfan Ikram, which were incorrectly given as Fan Lui and Arfan M. Ikram. In addition, the original version of this Article also contained errors in the author affiliations which are detailed in the associated Publisher Correction.

Contributor Information

David L. Duffy, Phone: +61 7 3362 0217, Email: David.Duffy@qimrberghofer.edu.au

Melanoma GWAS Consortium:

Jeffrey E. Lee, Myriam Brossard, Eric K. Moses, Fengju Song, Rajiv Kumar, Douglas F. Easton, Paul D. P. Pharoah, Anthony J. Swerdlow, Katerina P. Kypreou, Mark Harland, Juliette Randerson-Moor, Lars A. Akslen, Per A. Andresen, Marie-Françoise Avril, Esther Azizi, Giovanna Bianchi Scarrà, Kevin M. Brown, Tadeusz Dębniak, David E. Elder, Shenying Fang, Eitan Friedman, Pilar Galan, Paola Ghiorzo, Elizabeth M. Gillanders, Alisa M. Goldstein, Nelleke A. Gruis, Johan Hansson, Per Helsing, Marko Hočevar, Veronica Höiom, Christian Ingvar, Peter A. Kanetsky, Wei V. Chen, Maria Teresa Landi, Julie Lang, G. Mark Lathrop, Jan Lubiński, Rona M. Mackie, Graham J. Mann, Anders Molven, Srdjan Novaković, Håkan Olsson, Susana Puig, Joan Anton Puig-Butille, Graham L. Radford-Smith, Nienke van der Stoep, Remco van Doorn, David C. Whiteman, Jamie E. Craig, Dirk Schadendorf, Lisa A. Simms, Kathryn P. Burdon, Dale R. Nyholt, Karen A. Pooley, Nicholas Orr, Alexander J. Stratigos, Anne E. Cust, Sarah V. Ward, Hans-Joachim Schulze, Alison M. Dunning, Florence Demenais, and Christopher I. Amos

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-06649-5.

References

- 1.Tucker MA. Melanoma epidemiology. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North. Am. 2009;23:383–387. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsen CM, Carroll HJ, Whiteman DC. Estimating the attributable fraction for cancer: a meta-analysis of nevi and melanoma. Cancer Prev. Res (Phila.) 2010;3:233–45. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu G, et al. A major quantitative-trait locus for mole density is linked to the familial melanoma gene CDKN2A: a maximum-likelihood combined linkage and association analysis in twins and their sibs. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999;65:483–492. doi: 10.1086/302494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wachsmuth RC, et al. Heritability and gene-environment interactions for melanocytic nevus density examined in a U.K. adolescent twin study. J. Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:348–352. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falchi M, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants at 9p21 and 22q13 associated with development of cutaneous nevi. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:915–919. doi: 10.1038/ng.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duffy DL, et al. Multiple pigmentation gene polymorphisms account for a substantial proportion of risk of cutaneous malignant melanoma. J. Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:520–8. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han J, et al. A germline variant in the interferon regulatory factor 4 gene as a novel skin cancer risk locus. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1533–1539. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nan H, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies nidogen 1 (NID1) as a susceptibility locus to cutaneous nevi and melanoma risk. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20:2673–2679. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duffy DL, et al. IRF4 variants have age-specific effects on nevus count and predispose to melanoma. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;87:6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Law MH, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies five new susceptibility loci for cutaneous malignant melanoma. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:987–995. doi: 10.1038/ng.3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang J, et al. Genomic inflation factors under polygenic inheritance. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;19:807–12. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pickrell JK, et al. Detection and interpretation of shared genetic influences on 42 human traits. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:709–17. doi: 10.1038/ng.3570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibbs, D. C. et al. Association of interferon regulatory factor-4 polymorphism rs12203592 with divergent melanoma pathways. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 108, djw004 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Bataille V, et al. Nevus size and number are associated with telomere length and represent potential markers of a decreased senescence in vivo. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2007;16:1499–502. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iles, M. M. et al. The effect on melanoma risk of genes previously associated with telomere length. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 106, dju267 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Nan H, et al. Genome-wide association study of tanning phenotype in a population of European ancestry. J. Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2250–2257. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shoag J, et al. PGC-1 coactivators regulate MITF and the tanning response. Mol. Cell. 2013;49:145–157. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karami S, et al. Telomere structure and maintenance gene variants and risk of five cancer types. Int J. Cancer. 2016;139:2655–2670. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sokolenko Anna P., Bulanova Daria R., Iyevleva Aglaya G., Aleksakhina Svetlana N., Preobrazhenskaya Elena V., Ivantsov Alexandr O., Kuligina Ekatherina Sh., Mitiushkina Natalia V., Suspitsin Evgeny N., Yanus Grigoriy A., Zaitseva Olga A., Yatsuk Olga S., Togo Alexandr V., Kota Poojitha, Dixon J. Michael, Larionov Alexey A., Kuznetsov Sergey G., Imyanitov Evgeny N. High prevalence ofgermline mutations in-mutant breast cancer patients. International Journal of Cancer. 2014;134:2352–2358. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou Honglei, Rigoutsos Isidore. The emerging roles of GPRC5A in diseases. Oncoscience. 2014;1:765. doi: 10.18632/oncoscience.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biggs CM, et al. DOCK8 deficiency: insights into pathophysiology, clinical features and management. Clin. Immunol. 2017;181:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cancer Genome Atlas Network. et al. Genomic classification of cutaneous melanoma. Cell. 2015;61:1681–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kedziora KM, et al. Rapid remodeling of invadosomes by Gi-coupled receptors: dissecting the role of Rho GTPases. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:4323–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.695940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaysse A, et al. A comprehensive genome-wide analysis of melanoma Breslow thickness identifies interaction between CDC42 and SCIN genetic variants. Int J. Cancer. 2016;139:2012–2020. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reemann P, et al. Melanocytes in the skin--comparative whole transcriptome analysis of main skin cell types. PLoS One. 2014;9:e115717. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy C, Khaled M, Fisher DE. MITF: master regulator of melanocyte development and melanoma oncogene. Trends Mol. Med. 2006;12:406–14. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laurette, P. et al. Transcription factor MITF and remodeller BRG1 define chromatin organisation at regulatory elements in melanoma cells. Elife4, e06857 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Schoof, N., Iles, M. M., Bishop, D. T., Newton-Bishop, J. A. & Barrett, J. H. Pathway-based analysis of a melanoma genome-wide association study: analysis of genes related to tumour-immunosuppression. PLoS ONE 6, e29451 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Whiteman DC, et al. Melanocytic nevi, solar keratoses, and divergent pathways to cutaneous melanoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2003;95:806–12. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.11.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Visconti, A. et al. Genome-wide association study in 176,678 Europeans reveals genetic loci for tanning response to sun exposure. Nat. Commun.9, 1684 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.GTEx Consortium, et al. Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature. 2017;550:204–213. doi: 10.1038/nature24277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zalaudek I, et al. Age-related prevalence of dermoscopy patterns in acquired melanocytic naevi. Br. J. Dermatol. 2006;154:299–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelly JW, et al. Sunlight: a major factor associated with the development of melanocytic nevi in Australian schoolchildren. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1994;30:40–48. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(94)70005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bataille V, et al. The association between naevi and melanoma in populations with different levels of sun exposure: a joint case-control study of melanoma in the UK and Australia. Br. J. Cancer. 1998;77:505–10. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shain AH, Bastian BC. From melanocytes to melanomas. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2016;16:345–58. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolf Horrell EM, Jarrett SG, Carter KM, D’Orazio JA. Divergence of cAMP signalling pathways mediating augmented nucleotide excision repair and pigment induction in melanocytes. Exp. Dermatol. 2017;26:577–584. doi: 10.1111/exd.13291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinforma. Bioinforma. 2010;26:2190–2191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han B, Eskin E. Random-effects model aimed at discovering associations in meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;88:586–598. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boyd, A. et al. Cohort Profile: the ʽchildren of the 90sʼ - the index offspring of the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Int. J. Epidemiol. 42, 111–127 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Newton-Bishop J. A., et al. Melanocytic Nevi, Nevus Genes, and Melanoma Risk in a Large Case-Control Study in the United Kingdom. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2010;19:2043–2054. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Werner K. B., et al. The association between childhood maltreatment, psychopathology, and adult sexual victimization in men and women: results from three independent samples. Psychological Medicine. 2016;46:563–573. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715002056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mosing M. A., et al. Genetic Influences on Life Span and Its Relationship to Personality: A 16-Year Follow-Up Study of a Sample of Aging Twins. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2012;74:16–22. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182385784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yazar Seyhan, et al. Raine Eye Health Study: Design, Methodology and Baseline Prevalence of Ophthalmic Disease in a Birth-cohort Study of Young Adults. Ophthalmic Genetics. 2013;34:199–208. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2012.755632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hofman Albert, Murad Sarwa Darwish, van Duijn Cornelia M., Franco Oscar H., Goedegebure André, Arfan Ikram M., Klaver Caroline C. W., Nijsten Tamar E. C., Peeters Robin P., Stricker Bruno H. Ch., Tiemeier Henning W., Uitterlinden André G., Vernooij Meike W. The Rotterdam Study: 2014 objectives and design update. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2013;28:889–926. doi: 10.1007/s10654-013-9866-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mackey David A., MacKinnon Jane R., Brown Shayne A., Kearns Lisa S., Ruddle Jonathan B., Sanfilippo Paul G., Sun Cong, Hammond Christopher J., Young Terri L., Martin Nicholas G., Hewitt Alex W. Twins Eye Study in Tasmania (TEST): Rationale and Methodology to Recruit and Examine Twins. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2009;12:441–454. doi: 10.1375/twin.12.5.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are available from the authors upon application.