Abstract

The clustered regulatory interspaced short palindromic repeat-associated protein 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) system has developed into a powerful gene-editing tool that has been successfully applied to various plant species. However, studies on the application of the CRISPR/Cas9 system to cultivated Brassica vegetables are limited. Here, we reported CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in Chinese kale (Brassica oleracea var. alboglabra) for the first time. A stretch of homologous genes, namely BaPDS1 and BaPDS2, was selected as the target site. Several stable transgenic lines with different types of mutations were generated via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, including BaPDS1 and BaPDS2 double mutations and BaPDS1 or BaPDS2 single mutations. The overall mutation rate reached 76.47%, and these mutations involved nucleotide changes of fewer than 10 bp. The clear albino phenotype was observed in all of the mutants, including one that harbored a mutation within an intron region, thereby indicating the importance of the intron. Cleavage in Chinese kale using CRISPR/Cas9 was biased towards AT-rich sequences. Furthermore, no off-target events were observed. Functional differences between BaPDS1 and BaPDS2 were also assessed in terms of the phenotypes of the respective mutants. In combination, these findings showed that CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis can simultaneously and efficiently modify homologous gene copies of Chinese kale and provide a convenient approach for studying gene function and improving the yield and quality of cultivated Brassica vegetables.

Introduction

Genome-editing techniques using sequence-specific nucleases (SSNs) provide exceptionally powerful tools that cause targeted gene knockout or knockdown by introducing base insertions, deletions, or substitutions into specific DNA sequences, which enable precise genomic sequence modification. To date, several genome editing techniques have been reported, such as zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs)1–3, transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs)4,5, and the more recent clustered regulatory interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)-associated protein 9 (CRISPR/Cas9)-based methods6–8. ZFNs are a fusion of the transcription factor protein ZFA (Zinc finger activator) and FOKI (a endonuclease isolated from the bacterium Flavobacterium okeanokoites), while TALENs are constructed by fusing transcription activator-like (TAL) effectors and FOKI9. ZFNs and TALENs both can specifically recognize and bind to the specified DNA sequence to form a cleavable FOKI dimer, and then induce DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) at the target site4. ZFNs and TALENs have been successfully applied in editing plant genomes, but there still exist some deficiencies like consuming time, expensiveness and high complexity of vector construction10. CRISPR/Cas9 derived from an adaptive immune system in bacteria and archaea, and it can perform precise genome editing of target genes in a variety of organisms through artificial manipulation. Due to its low cost, design flexibility, versatility, and high efficiency, the CRISPR/Cas9 system provides a solution for the drawbacks of ZFNs and TALENs, and has become the third-generation genome editing technique following ZFNs and TALENs11.

The principle of CRISPR/Cas9 is that CRISPR RNA (crRNA) binds to trans activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA) by base pairing to form a tracrRNA/crRNA binary complex, which guides the endonuclease Cas9 to cleave the target double-stranded DNA. The tracrRNA/crRNA binary complex can be substituted by an engineered single guide RNA (sgRNA)12. Critically, the Cas9 protein recognizes an NGG protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) which flanks the 3′ end of the target sequence, and then achieve the cleavage of the target site13. The resulting DSBs trigger non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homologous recombination (HR) repair pathways, which may lead to gene mutations14. If an insertion, deletion, or substitution occurs at the coding region of the gene, it will probably cause a frameshift mutation in the target gene and may remarkably affect gene function15.

CRISPR/Cas9 technology has been widely and successfully applied to host DNA mutagenesis in a variety of plants, such as Nicotiana benthamiana16, Arabidopsis17, wheat18, rice11, Zea19, sorghum20, potato21, sweet orange22, tomato23, grape24, populus25, citrus26, and apple27. However, despite the existence of a diverse range of Brassica plants, the CRISPR/Cas9 system has only been successfully applied to oilseed rape28,29 and Brassica oleracea30. Brassica vegetables are a large group of agriculturally important vegetables that have high nutritional and economic value. Chinese kale (B. oleracea var. alboglabra) is an original Chinese Brassica vegetable that is widely distributed in southern China and Southeast Asia. In addition to its good flavor, Chinese kale also has high nutritional value due to its high levels of antioxidants and anticarcinogenic compounds, including vitamin C, carotenoids, total phenolics, and glucosinolates31,32. Here, we report the application of the CRISPR/Cas9 technology in Chinese kale (a cultivated Brassica vegetable) for the first time.

The phytoene desaturase (PDS) gene, which encodes a key enzyme involving carotenoid biosynthesis, is commonly selected as the target gene for CRISPR/Cas9 experiments in plant, because the albino phenotype caused by the disruption of PDS can be easily recognized16. Previously, we cloned and analyzed two homologous gene copies in Chinese kale, namely BaPDS1 and BaPDS233. In this study, we utilized these two BaPDSs as target genes in Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation. The present study showed the simultaneous site-directed mutagenesis of these homologous genes in Chinese kale, which provided a theoretical foundation for the application of the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technique in Chinese kale and other Brassica vegetables.

Results

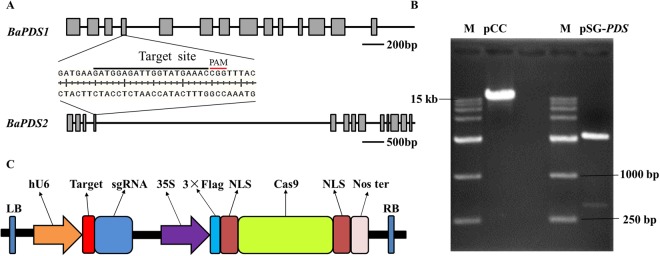

SgRNA design and vector construction

The common target site was selected in the fourth exon sequence of both BaPDS1 and BaPDS2. The target sequence is GATGGAGATTGGTATGAAACCGG (Fig. 1A). The target sequences for BaPDS1 and BaPDS2 are completely identical, and the GC content of gRNA is 40%. The recombinant plasmids of pSG-BaPDS and pCC were digested with EcoRI-HF and XbaI-HF, respectively (Fig. 1B). The fragment of the sgRNA expression cassette was purified by gel recovery and ligated into the digested pCC. The recombinant plasmid of pCC-target-sgRNA was successfully obtained for subsequent analysis (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

A map of the constructed vector. (A) Schematic of the BaPDSs gene fragment indicating the sgRNA target site and sequence.  indicates exon.

indicates exon.  indicates intron. (B) Gel electrophoresis of the recombinant plasmid of pSG-BaPDS and pCC. M, DL15000 marker. (C) Structure of the CRISPR/Cas9 binary vectors for Chinese kale transformation. The Cas9 cassette was driven by the 35S promoter, while sgRNA was controlled by the hU6 promoter. The 3 × Flag is a label which can be used to identify the transgenic plants. NLS, nuclear localization sequence.

indicates intron. (B) Gel electrophoresis of the recombinant plasmid of pSG-BaPDS and pCC. M, DL15000 marker. (C) Structure of the CRISPR/Cas9 binary vectors for Chinese kale transformation. The Cas9 cassette was driven by the 35S promoter, while sgRNA was controlled by the hU6 promoter. The 3 × Flag is a label which can be used to identify the transgenic plants. NLS, nuclear localization sequence.

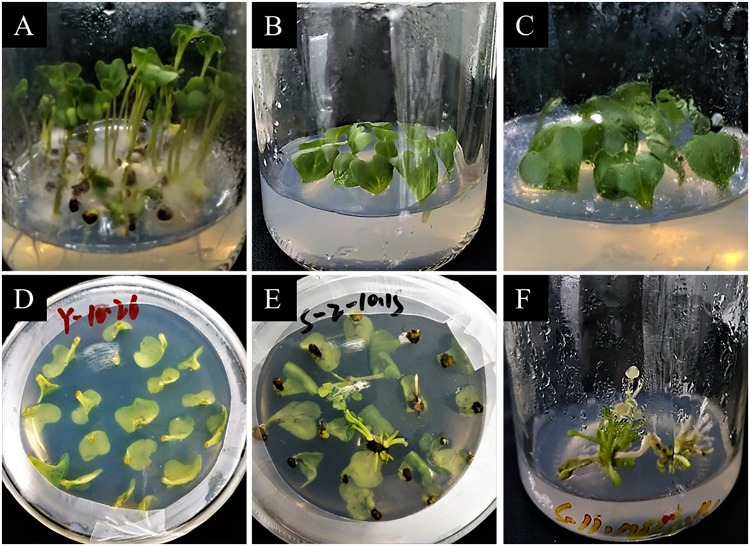

CRISPR/Cas9 transformation efficiency in Chinese kale

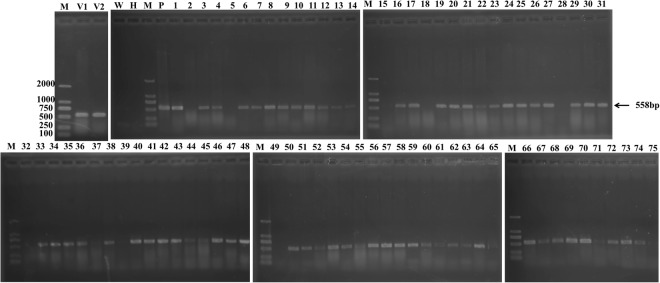

Using the established genetic transformation protocol of our laboratory (Fig. 2), about 5,000 explants were used for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. Seventy-five hygromycin-resistant plants were successfully obtained (1.5%). To confirm the existence of the transformed constructs in the transgenic lines, genomic DNA was extracted from each hygromycin-resistant plant. PCR amplification with specific primers targeting the hygromycin gene was conducted. A 558-bp target band was successfully amplified using the empty vector, plasmid (positive control), and the 68 resistant plants. No products were obtained with the template in water, wild-type plants (negative control), and seven out of the 75 plants (lines 2, 5, 15, 18, 28, 32, and 49) (Fig. 3, Supplemental Fig. 1). These results indicated that the target expression cassette was successfully transferred into the 68 Chinese kale lines. In addition, the false positive rate in this experiment was only 9.33%.

Figure 2.

The procedure of Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation in Chinese kale. (A) Aseptic seedling culture, (B) pre-culture, (C) co-culture, (D) delayed screening, (E) resistance screening, (F) subculture.

Figure 3.

PCR detection of the hygromycin-resistant gene for the estimation of transformation efficiency. M: DL2000 maker; V1, V2: empty vector was used as a positive control; P: plasmid containing the vector and sgRNA also was used as a positive control; H,W: H2O and the gDNA of the wild-type was used as a negative control; 1–75: indicates the resistant plant line number. The arrow points to the aim band.

Statistical analysis of the BaPDSs mutation efficiency

To detect the mutation efficiency of CRISPR/Cas9, PCR was performed using specific primers (Table 1) and the 68 transgenic plants, followed by sequencing of the resulting PCR products. When both genes were simultaneously mutated, they were called double mutations, and when there was only one gene mutated, they were called single mutations. Approximately 76.47% of the transgenic plants harbored mutations, including 14 that were BaPDS1 and BaPDS2 double mutants, accounting for 20.59% of the total number of transgenic plants; 10 BaPDS1 single mutants, accounting for 14.70%; and 28 BaPDS2 single mutants, accounting for 41.18% (Table 2). Overall, the ratio of double mutations accounted for about one-fifth of the transgenic plants, and the proportion of the single mutant-type was more than a half, indicating that CRISPR/Cas9 system-induced gene editing has superior mutation efficiency in Chinese kale.

Table 1.

Primers used in the study.

| Primer names | Sequence of primers (5′-3′) | Aims |

|---|---|---|

| sgRNA-BaPDSs-F | GATGGAGATTGGTATGAAAC | Synthesis of the target site |

| sgRNA-BaPDSs-R | GTTTCATACCAATCTCCATC | |

| BaPDS1-CRISPR test-F | CCTGCAAAGCCTTTAAAAGTTGTCATT | Detection of the mutation in transgenic plants |

| BaPDS1-CRISPR test-R | CCAAGTTCTCCAAATAAGTTCTGCACG | |

| BaPDS2-CRISPR test-F | CCTGCAAAGCCTTTAAAAGTTGTGATC | |

| BaPDS2-CRISPR test-R | GCTATAGAAGATAAGAGCCGAGCCT | |

| Hyg-F | CGATTGCGTCGCATCGACC | Detection of the hygromycin resistance gene |

| Hyg-R | TTCTACAACCGGTCGCGGAG | |

| Off-target1-F | ATTCCTTGGAATTAGCTCTTCACTTGAC | Off-target analysis |

| Off-target1-R | GATGGGGACTCGAATCTTATCTGCC | |

| Off-target2-F | CAGGAATGCATGGGAAAGCATGAATG | |

| Off-target2-R | ATGATGCAACCGGGTAGTTTAATCG | |

| Off-target3-F | CATCATGAGTGGGGACAAGTTGTG | |

| Off-target3-R | TCAGCGTCCATGAGAGGTAAAGGG |

Table 2.

Percentage of transgenic plants examined with BaPDSs mutations in Chinese kale.

| Mutation gene | Number of mutants | Mutation rate (%) | Total number of strains detected | Total mutation rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BaPDS1 + BaPDS2 | 14 | 20.59 | 68 | 76.47 |

| BaPDS1 | 10 | 14.70 | ||

| BaPDS2 | 28 | 41.18 |

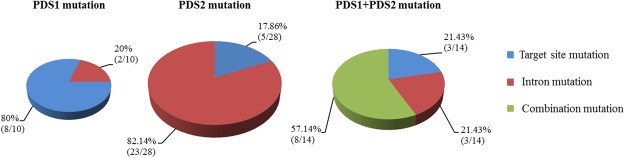

Analysis of the BaPDSs mutations

Fifty-two BaPDSs mutants were obtained by sequencing confirmation. The distribution of mutations of CRISPR/Cas9-editing of the two homologous gene copies was investigated (Fig. 4). Among the BaPDS1 and BaPDS2 double mutants, the proportion of both mutations at the target site or within introns respectively accounted for 21.43% (3/14) of the total number of mutations, and the proportion of mixed mutations was 57.14% (8/14). Among the BaPDS1 single mutants, 80% (8/10) were situated at the target site, whereas 20% (2/10) occurred in intronic area. Among the BaPDS2 single mutants, the frequency of mutations at the target site and within introns was 17.86% (5/28) and 82.14% (23/28), respectively (Fig. 4). These results suggest that the CRISPR/Cas9 system can simultaneously edit both copies of the genes using the sgRNA, which targets the consensus sequence of the two homologous genes in Chinese kale.

Figure 4.

Analysis of the number and proportion of mutation sites in Chinese kale mutants. Mixed type means that one of the two genes is mutated at the target site and the other is mutated within an intron.

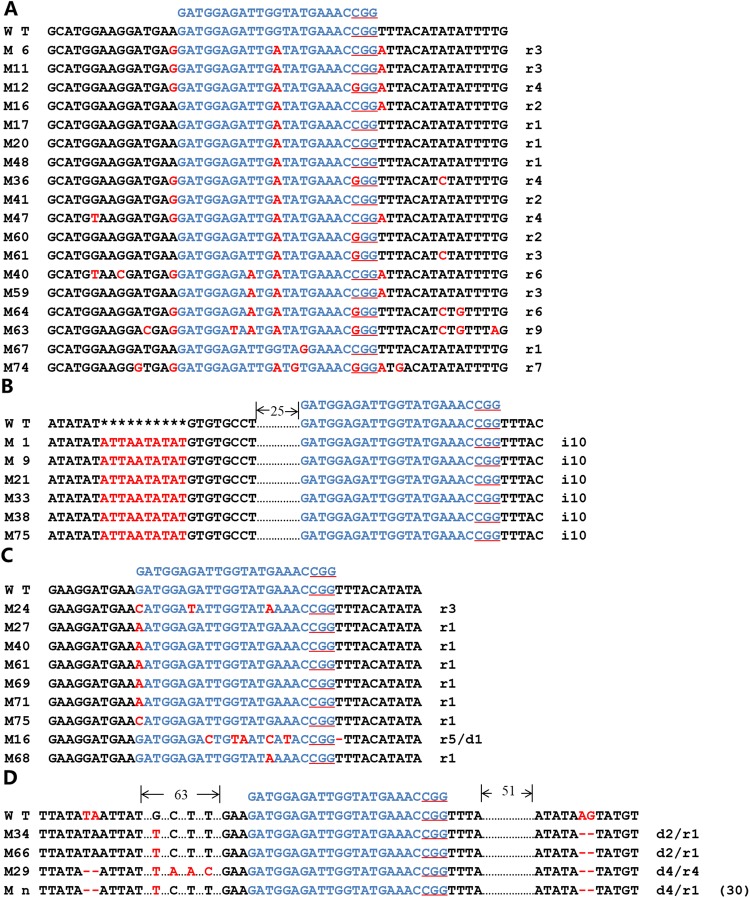

Analysis of the BaPDS1 mutations

The mode of the BaPDS1 mutation was further analyzed. A total of 24 BaPDS1 mutations were identified, including 18 that have one- to nine-base single-nucleotide substitutions at the target site (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, 17 mutants showed a G to A substitution at the ninth base upstream of the PAM locus. This substitution is predicted to result in an amino acid change from tryptophan (Trp) to a stop codon, thereby generating a truncated (nonsense) BaPDS1 protein. A single mutant harbored a G to T substitution six bases upstream of the PAM locus. Similarly, the encoded tyrosine (Tyr) was substituted by a stop codon, thereby also resulting in a truncated protein (Fig. 5A). In addition, we found that among the remaining six BaPDS1 mutants, a 10-bp (ATTAATATAT) insertion was detected in the third intron of BaPDS1 (Fig. 5B). However, regardless of the position of the mutation (target site or intron), the plants showed the same albino phenotype (Fig. 6D,G).

Figure 5.

CRISPR/Cas9 system-induced mutation detection in Chinese kale mutants. (A) BaPDS1 mutations at the target site; (B) BaPDS1 mutations within introns; (C) BaPDS2 mutations at the target site; (D) BaPDS2 mutations within introns. The target sequence is indicated in blue, the PAM sequence (NGG) is underlined in red, mutated bases are indicated in red font, the short line represents the deletion base, and the asterisks indicate the spacing between bases. i #, # number of base insertions. r #, # number of base replacements. d #, # number of base deletions. The number of identical mutations is indicated in parentheses. Mn contains strains M4, M7, M8, M9, M10, M11, M12, M13, M20, M23, M26, M31, M32, M33, M36, M37, M38, M41, M42, M44, M45, M48, M50, M55, M57, M60, M65, M70, M72, M73.

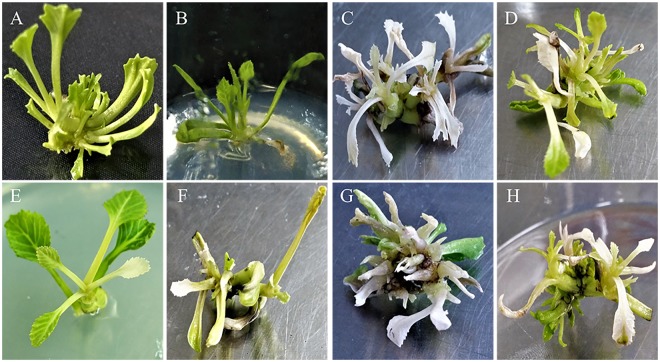

Figure 6.

The albino phenotype of the BaPDS mutants after transformation with the CRISPR/Cas9 system. (A) Non-transgenic plant; (B) Transgenic plants with an empty vector (containing T-DNA); (C) BaPDS1 and BaPDS2 double mutant at the target site; (D) BaPDS1 single mutant at the target site; (E) BaPDS2 single mutant at the target site; (F) BaPDS1 and BaPDS2 double mutants within the introns; (G) BaPDS1 single mutant within the introns; (H) BaPDS2 single mutant within the introns.

Analysis of the BaPDS2 mutations

Similarly, the mode of the BaPDS2 mutations was also investigated. Among the 42 BaPDS2 mutants, nine were found to be mutated at the target site, resulting in a frameshift mutation or amino acid substitution (Fig. 5C). Thirty-one mutants had an AG deletion in the fourth intron and a TA deletion in the third intron, and the remaining two had an AG deletion in the fourth intron. (Fig. 5D). Similarly, regardless of the site of the mutation, BaPDS2 single mutants exhibited a similar albino phenotype (Fig. 6E,H).

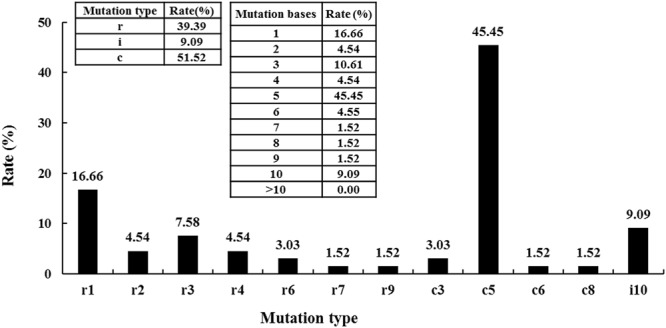

Patterns and frequency of the BaPDSs mutations

A variety of mutation types were observed in this survey, including substitutions, insertions, and combinatorial mutagenesis (substitutions and deletions occurring simultaneously) (Fig. 7). Among these, up to 51.52% of the mutations were combined mutations, followed by substitutions (39.39%). Insertion mutations accounted for only 9.09% of the observed genomic alterations. All of the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutations were short nucleotide changes (≤10 bp) (100%), and 5-bp-long combined mutations were the predominant type, accounting for 45.45% of the observed mutations. All of the insertion mutations were involved in the ATTAATATAT sequence.

Figure 7.

Types and frequency of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutations in Chinese kale. The graph includes the sequencing data of all of the mutants. The illustration on the left shows the types of mutations. The illustration on the right shows the frequency of the mutations of different lengths. X-axis: r #, the number of base replacements; c #, the base number of combined mutations; i #, the number of base insertions.

Analysis of potential off-targets

To assess whether the CRISPR/Cas9 system specifically edits the BaPDS genes, three potential off-target sequences were selected using the CRISPR-P web tool. Reports have indicated that the ‘seed sequence’, which consists of 12 nucleotides located at the target site and adjoining the PAM, is crucial for specific recognition and efficient targeted cleavage of the Cas9 protein15,34. Among the three potential off-target sites selected, off-target sites 1 and 3 only showed a 1-bp mismatch in the seed sequence, and off-target site 2 had a 2-bp mismatch in the seed sequence (Table 3). All three potential off-target sites were PCR amplified using specific primers (Table 1). Sequencing did not detect any mutations within all of the tested sites. These results indicate that CRISPR/Cas9-induced target mutagenesis is highly specific to the BaPDSs in Chinese kale and does not have off-target effects.

Table 3.

Potential off-target analysis.

| Target | Sequence | Mismatches | Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target site | GATGGAGATTGGTATGAAACCGG | ||

| Off-target site1 | TATAGTGATTAGTATGAAACGGG | 4 | 0.0% |

| Off-target site2 | AAAGGAGATTGCAATGAAACTGG | 4 | 0.0% |

| Off-target site3 | GGTGGAGCTTGTTATGAAACTGG | 3 | 0.0% |

The seed sequence is underlined.

Albino phenotype of the BaPDSs mutants

All of the obtained 52 PDS mutants showed a clear albino phenotype compared to the wild-type (Fig. 6). Interestingly, the leaves of plants with edited PDS1 and PDS2 were pure albino (Fig. 6C), whereas those with PDS1 or PDS2 single mutations either at the target loci or within introns resulting in a mosaic albino phenotype belonged to chimeric mutants (Fig. 6D–H). These results indicate that the gene function of BaPDSs had been knocked-out or knocked-down.

Discussion

Brassica vegetables have drawn increasing attention owing to its high economic value. Based on morphological characteristics, they are divided into three types of B. rapa, B. oleracea, and B. juncea. Chinese kale is one of the most important vegetables within B. oleracea31,32. It has 18 chromosomes and belongs to the CC genome type35. As a diploid, Chinese kale is suitable for gene modification and offspring inheritance studies. The screening of targeted mutants has long been employed as a useful strategy for plant functional genomics and crop improvement. However, this approach is extremely laborious and time-consuming as it generally entails traditional mutagenesis methods36,37. In recent years, precise, efficient, and multi-site mutagenesis has been achieved in plants using genome editing technology. As the third-generation genome editing technology, the CRISPR/Cas9 system has been applied in various plants since its emergence. Numerous studies have used protoplast transient transformation to integrate the CRISPR/Cas9 system, which can rapidly and efficiently screen the target site and detect mutations13,18. However, unlike model plants such as Arabidopsis and tobacco, protoplast technology (isolation, purification, and especially regeneration) remains a major obstacle in accessing mutated Brassica vegetables, thereby limiting its practical application to this particular crop species. Therefore, Agrobacterium-mediated stable transformation was selected in this study, despite the efficiency of transient transformation being higher than that of stable transformation38. As expected, a variety of Chinese kale mutants were obtained using the CRISPR/Cas9 system, with relatively high efficiency (76.47%).

Multi-site precise editing is very important for investigations into complex traits and functionally redundant genes. However, the high genetic redundancy in Brassica crops makes it difficult to alter a trait by random mutagenesis and to obtain corresponding mutants, especially recessive mutants28,39. The innate ability of Cas9 to simultaneously edit multiple loci within the same individual has numerous potential applications, such as the mutation of multiple members of a gene family or functionally related genes that control complex traits40. Targeted mutagenesis of duplicated genes in Camelina sativa was conducted using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing to generate triple mutants of the three delta-12-desaturase (FAD2) genes39. A four-allele mutated line of the granule-bound starch synthase (GBSS) gene obtained by CRISPR/Cas9 resulted in the complete knockout of GBSS enzyme activity in potato14. In this study, double mutants of BaPDS1 and BaPDS2 were obtained, and their proportion amounted to about 20% of the total number of transgenic plants (Table 2). In this study, we selected only one common and conservative co-target site in two homologous genes (BaPDS1 and BaPDS2) of Chinese kale rather than using the tandem multiplex gRNA method that has been employed in previous studies13,41 because the mutation efficiency induced by multiplex gRNA is significantly lower than that of a single gRNA13. Our results confirmed the powerful capability of the CRISPR/Cas9 system in inducing multiplex mutagenesis simultaneously, and furtherly broadened its application in various plant species.

Mutation types are affected by different factors and vary among plant species. Previous reports have shown that 1-bp insertions and deletions predominantly occur in rice11 and Arabidopsis17, deletions involving a few bases are the major types of mutations in tobacco13, and the proportion of substitutions induced by BnaA6.RGA-sgRNA1 in B. napus are much higher than other sgRNAs42. In this study, short nucleotide substitutions predominantly occurred in Chinese kale. This discrepancy may be caused by differences in intrinsic DNA-repair mechanisms among plant species, transformation methods, target genes, or target sites11,42.

In this study, some mutations did not occur precisely at the target site, but within flanking regions. The BaPDS2 intronic mutation in 33 lines involved the sequence AAG (Fig. 5D), which is another PAM (NAG)43 besides NGG44 for Cas9 cleavage. Conversely, there were six lines that harbored a 10-bp insertion (ATTAATATAT). The mutation involved the third intron of BaPDS1, which is AT-rich (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, there were 31 BaPDS2 mutations with a 2-bp deletion (TA) in the third intron, which is also AT-rich (Fig. 5D). Most of these mutations occurred at AT-rich sites. These findings indicate that Cas9 preferentially cuts and edits AT-rich sequences in Chinese kale, which is similar to that observed in rice11, citrus45, and Camelina46. However, this hypothesis requires further confirmation.

Off-target effects are usually caused by the base-mismatches between sgRNA and the genomic DNA sequences, which hinders further application of the CRISPR/Cas9 technology47,48. However, there is growing evidence that off-targets might not be a critical problem in plants because its actual risk may be low during tissue culture-based transformation or other mutagenesis treatments40. In this study, we also assessed for potential off-target sites, but found none. These results corroborate the previous conclusion that Cas9/sgRNA specificity is determined by the position and number of mismatches in sgRNA target pairing15, and a well-designed specific sgRNA, such as the sgRNA in this study, would not target non-targeted sites11. However, this study was not a comprehensive evaluation of the specificity for targeted gene editing using the CRISPR/Cas9 system in Chinese kale, and more candidate off-target sites need to be analyzed in the future.

Numerous studies have shown that intronic sequences are closely related to the expression of plant functional genes. Recent investigations also have revealed that a large number of microRNAs are located within the introns of protein-coding genes, linking their expression to the promoter-driven regulation of the host gene49,50. For instance, miR838 that is derived from a hairpin within intron 14 of the DC1 could mediate gene expression by auto-regulation in A. thaliana51. In this study, we found several mutations within the third and fourth introns of BaPDSs, and these mutation modalities were relatively higher in frequency (Fig. 5B,D). Furthermore, all of the intron mutations resulted in mosaic albino phenotypes (Fig. 6F–H), indicating a knock-down in the function of the BaPDS genes. These introns may be involved in gene expression in Chinese kale. Nevertheless, the reasons why intron mutations cause loss of gene function remain unclear and will be further studied in subsequent studies.

Generating distinct mutants of multiple copies of homologous genes could be helpful in elucidating the function of the respective genes, and successful examples in plants, such as Camelina sativa39 and potato14, were previously reported. Although we have cloned BaPDS1 and BaPDS2 in Chinese kale, as well as analyzed their expression patterns in an earlier study33, their respective functions remain elusive. As expected, all three types of mutants (PDS1 and PDS2 double mutations and PDS1 or PDS2 single mutations) were obtained simultaneously in this study. The pure albino phenotype of the double mutants and the mosaic albino phenotype of the BaPDS1 and BaPDS2 single mutants (Fig. 6) indicate that the functions of BaPDS1 and BaPDS2 are distinct and also partially compensated. In addition, the loss of function of either gene would be lethal to Chinese kale plants, suggesting that both are essential for carotenoid biosynthesis.

The rapid development of the CRISPR/Cas9 system has provided a robust platform for plant genomic studies. The present investigation achieved fixed-point editing of the Chinese kale genome using the CRISPR/Cas9 system via stable transformation for the first time. Additionally, a single target site for simultaneously mutating multi-genes to create various mutation materials was also achieved. The findings of the present study strengthen the application of the CRISPR/Cas9 system in cultivated Brassica vegetables, and enrich our understanding of the mutation mode of CRISPR/Cas9 in Brassica crops, and provide a foundation for the further study of gene function through the creation of mutants.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

The Chinese kale cultivar ‘Sijicutiao’ which is a multi-generation inbred from our laboratory was used in the study. Sterile seedlings grown on 1/2 Murashige and Skoog (1/2 MS) medium with 0.8% phytagar, and they were placed on tissue culture chambers with temperature of 25/20 °C (day/night), light cycle of 16/8 h (day/night), and light intensity of 100 μmol m−2 s−1. After seven days, cotyledons with 1- to 2-mm long petioles were cut and used as explants in Agrobacterium-mediated transformation.

Vector construction

The CRISPR/Cas9 vector supports from our laboratory52. The plasmid pX330, pCAMBIA1302, and pUC19 were used as materials for the construction of the CRISPR/Cas9 vector using recombinant DNA technology. The mgfp sequence in pCAMBIA1302 was successfully replaced by the Cas9 sequence from pX330, and the recombinant plasmid was constructed, hereafter referred to as pCC. The sgRNA sequence in pX330 was imported into the multiple cloning site region of the pUC19 plasmid, and the recombinant plasmid was designated as pSG. pCC and pSG comprised the two basic vectors of the CRISPR/Cas9.

According to our previous report, the BaPDS gene family has two members, BaPDS1 (GenBank Accession No. KX426039) and BaPDS2 (GenBank Accession No. KX426040)33. Sequence analysis of BaPDSs was conducted using the web tools of CRISPR DESIGN (http://crispr.mit.edu/) and ZiFiT Targeter Version 4.2 (http://zifit.partners.org/ZiFiT/CSquare9 Nuclease.aspx), and the common target sequence of BaPDS1 and BaPDS2 was designed. The synthesized oligos were annealed and inserted into the BbsI sites of the pSG. Then, the recombinant plasmid (pSG-BaPDS) was digested by EcoRI-HF and XbaI-HF, and the sgRNA expression cassette was inserted into the multiple cloning site region of the pCC vector to generate pCC-target-sgRNA for Chinese kale transformation. All of the above vectors were verified by restriction and sequencing.

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Chinese kale plants

The transformation of Chinese kale was conducted as previously described, with modifications53,54. The explants pre-cultured for 3 d in Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium with 0.5 mg/L 2,4-D and 0.8% phytagar were infected with the Agrobacterium strain GV3101 (optical density at 600 nm between 0.6 and 0.8) by immersion for 1–2 min. The explants were co-cultivated with Agrobacterium strain GV3101 for three days in MS medium with 0.03 mg/L naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA), 0.75 mg/L boric acid (BA), and 0.8% phytagar, and then transferred to the MS medium supplemented with 0.03 mg/L NAA, 0.75 mg/L BA, 0.8% phytagar, 325 mg/L carbenicillin, and 325 mg/L timentin for a week. Hygromycin-resistant shoots regenerated on the same medium with 12 mg/L hygromycin B were transferred to tissue culture bottles containing the subculture medium. After three months, hygromycin-resistant plantlets were obtained and prepared for subsequent analysis.

Transformation efficiency detection

Genomic DNA was extracted from the shoots of hygromycin-resistant and wild-type plants using a standard cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method. To confirm the Chinese kale transformants, PCR amplification using the specific primers HygR-F and HygR-R (Table 1), which were designed to flank the hygromycin sequence contained in the vector, was performed. The PCR products were detected using electrophoresis to calculate transformation efficiency. The transformants without the hygromycin gene were not used for further analysis.

Mutation detection

To evaluate mutations introduced in the CRISPR/Cas9 transgenic plants, genomic DNA of each positively transgenic shoot was amplified using specific primers, which were designed to amplify the 816-bp and 702-bp flanking regions of the target site of BaPDS1 and BaPDS2, respectively. For genotyping of the transgenic plants, the PCR products were sequenced. DNAMAN software (version 6.0; Lynnon Corporation, Canada) was used to compare the sequence, the mutation rate was calculated, and all of the sequencing data were collected to analyze the mutation type.

Off-target analysis

Potential off-target sites were identified with the CRISPR-P55 online software (http://crispr.hzau.edu.cn/CRISPR2/) using the full 20-bp target sequence in a BLAST analysis. These top-ranking potential off-target sites containing 1–2 bp mismatches in the 12-bp seed sequence were selected (Table 3). The sequences surrounding the potential off-target sites were amplified using specific primers (Table 1), and the PCR products were analyzed by Sanger sequencing.

Electronic supplementary material

Figure S1. Original image shows the PCR detection of the hygromycin-resistant gene for the estimation of transformation efficiency.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31500247), Key Project of Department of Education of Sichuan Province (14ZA0016), and National Student Innovation Training Program (201710626030).

Author Contributions

B.S. and A.Z. equally contributed to the work. Z.F. and H.T. jointly designed the research. H.T. supervised the project. A.Z., M.J., S.X. and Q.Y. performed most of the experiments. B.S., L.J., Q.C. M.L. and Y.W. analyzed the data. B.S., Y.Z., Y.L. and X.W. prepared the figures. B.S., A.Z. and Z.F. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Bo Sun and Aihong Zheng contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Fen Zhang, Email: zhangf_12@163.com.

Haoru Tang, Email: htang@sicau.edu.cn.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-34884-9.

References

- 1.Ainley WM, et al. Trait stacking via targeted genome editing. Plant Biotechnol J. 2013;11:1126–1134. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bibikova M, Golic M, Golic KG, Carroll D. Targeted chromosomal cleavage and mutagenesis in Drosophila using zinc finger nucleases. Genetics. 2002;161:1169–1175. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.3.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dreier B, et al. Development of zinc finger domains for recognition of the 5′-CNN-3′ family DNA sequences and their use in the construction of artificial transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:35588–35597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102604200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christian M, et al. Targeting DNA double-strand breaks with TAL effector nucleases. Genetics. 2010;186:757–761. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.120717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li T, et al. TAL nucleases (TALNs): hybrid proteins composed of TAL effectors and FokI DNA-cleavage domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:359–372. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cong L, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mali P, et al. Cas9 transcriptional activators for target specificity screening and paired nickases for cooperative genome engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:833–838. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shalem O, Sanjana NE, Zhang F. High-throughput functional genomics using CRISPR-Cas9. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16:299–311. doi: 10.1038/nrg3899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim YG, Cha J, Chandrasegaran S. Hybrid restriction enzymes: zinc finger fusions to Fok I cleavage domain. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1156–1160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaj T, Gersbach CA, Barbas CR. ZFN, TALEN and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2013;31:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.tbtech.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang H, et al. The CRISPR/Cas9 system produces specific and homozygous targeted gene editing in rice in one generation. Plant Biotechnol. 2014;J12:797–807. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan C, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated efficient and heritable targeted mutagenesis in tomato plants in the frst and later generations. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24765. doi: 10.1038/srep24765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao JP, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis in Nicotiana tabacum. Plant Mol Biol. 2015;87:99–110. doi: 10.1007/s11103-014-0263-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersson M, et al. Efficient targeted multiallelic mutagenesis in tetraploid potato (Solanum tuberosum) by transient CRISPR-Cas9 expression in protoplasts. Plant Cell Rep. 2017;36:117–128. doi: 10.1007/s00299-016-2062-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jinek M, et al. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nekrasov V, Staskawicz B, Weigel D, Jones JD, Kamoun S. Targeted mutagenesis in the model plant Nicotiana benthamiana using Cas9 RNA-guided endonuclease. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:691–693. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng ZY, et al. Multigeneration analysis reveals the inheritance, specificity, and patterns of CRISPR/Cas9-induced gene modifications in Arabidopsis. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:4632–4637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400822111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang YP, et al. Simultaneous editing of three homoeoalleles in hexaploid bread wheat confers heritable resistance to powdery mildew. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:947–951. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang Z, Zhang K, Chen KL, Gao C. Targeted mutagenesis in Zea mays using TALENs and the CRISPR/Cas system. J Genet Genomics. 2014;41:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang WZ, Zhou HB, Bi HH, Fromm M, Yang B. Demonstration of CRISPR/Cas9/sgRNA-mediated targeted gene modification in Arabidopsis, tobacco, sorghum and rice. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e188. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang S, et al. Efficient targeted mutagenesis in potato by the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Plant Cell Rep. 2015;34:1473–1476. doi: 10.1007/s00299-015-1816-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jia H, Wang N. Targeted genome editing of sweet orange using Cas9/sgRNA. PLOS ONE. 2014;9:1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu C, Park SJ, Van Eck J, Lippman ZB. Control of inflorescence architecture in tomato by BTB/POZ transcriptional regulators. Gene Dev. 2016;30:2048–2061. doi: 10.1101/gad.288415.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakajima I, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis in grape. PLOS ONE. 2017;12:1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan D, et al. Efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis in populus in the first generation. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12217. doi: 10.1038/srep12217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peng AH, et al. Engineering canker-resistant plants through CRISPR/Cas9-targeted editing of the susceptibility gene CsLOB1promoter in citrus. Plant Biotechnol J. 2017;15:1509–1519. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishitani C, et al. Efficient genome editing in apple using a CRISPR/Cas9 system. Sci Rep. 2016;6:31481. doi: 10.1038/srep31481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braatz J, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 targeted mutagenesis leads to simultaneous modification of different homoeologous gene copies in polyploid oilseed rape (Brassica napus) Plant Physiol. 2017;172:935–942. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.00426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li, C. et al. An Efficient CRISPR/Cas9 platform for rapidly generating simultaneous mutagenesis of multiple gene homoeologs in allotetraploid oilseed rape. Front Plant Sci9, 442, 10.3389/fpls.2018.00442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Lawrenson T, et al. Induction of targeted, heritable mutations in barley and Brassica oleracea using RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease. Genome Biol. 2015;16:258. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0826-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He HJ, Chen H, Schnitzler WH. Glucosinolate composition and contents in Brassica Vegetables. Scientia Agricultura Sinica. 2002;35:192–197. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:0578-1752.2002.02.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun B, Yan HZ, Liu N, Wei J, Wang QM. Effect of 1-MCP treatment on postharvest quality characters, antioxidants and glucosinolates of Chinese kale. Food Chem. 2012;131:519–526. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.09.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun B, et al. Cloning and expression analysis of BaPDS1 and BaPDS2 In Brassica alboglabra. Acta Horticulturae Sinica. 2016;43:2257–2265. doi: 10.16420/j.issn.0513-353x.2016-0480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang W, Bikard D, Cox D, Zhang F, Marrafni LA. RNA-guided editing of bacterial genomes using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:233–239. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xia X, et al. Optimization of chromosome preparation and karyotype analysis of yellow-flower Chinese kale. Journal of Zhejiang University (Agriculture & Life Sciences) 2016;42:527–534. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9209.2015.06.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colbert T, et al. High throughput screening for induced point mutations. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:480–484. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Till BJ, et al. Large-scale discovery of induced point mutations with high-throughput. TILLING. Genome Res. 2003;13:524–530. doi: 10.1101/gr.977903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tian SW, et al. Efficient CRISPR/Cas9-based gene knockout in watermelon. Plant Cell Rep. 2017;36:399–406. doi: 10.1007/s00299-016-2089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morineau C, et al. Selective gene dosage by CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in hexaploid Camelina sativa. Plant Biotechnol J. 2017;15:729–739. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma XL, et al. A robust CRISPR/Cas9 system for convenient, high-efficiency multiplex genome editing in monocot and dicot plants. Mol Plant. 2015;8:1274–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qi WW, et al. High-efficiency CRISPR/Cas9 multiplex gene editing using the glycine tRNA-processing system-based strategy in maize. BMC Biotechnol. 2016;16:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12896-016-0289-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang H, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing efficiently creates specific mutations at multiple loci using sgRNA in Brassica napus. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7489. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07871-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hsu PD, et al. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:827–832. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gasiunas G, Barrangou R, Horvath P, Siksnys V. Cas9-crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:2579–2586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208507109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jia H, et al. Genome editing of the disease susceptibility gene CsLOB1 in citrus confers resistance to citrus canker. Plant Biotechnol. 2017;J15:817–823. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiang W, et al. Significant enhancement of fatty acid composition seeds of the allohexaploid, Camelina stativa, using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. Plant Biotechnol J. 2017;15:648–657. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duan J, et al. Genome-wide identification of CRISPR/Cas9 off-targets in human genome. Cell Res. 2014;24:1009–1012. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fu Y, et al. High-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:822–826. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lutter D, Marr C, Krumsiek J, Lang EW, Theis FB. Intronic microRNAs support their host genes by mediating synergistic and antagonistic regulatory effects. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:224. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao DY, Song GQ. Rootstock-to-scion transfer of transgene-derived small interfering RNAs and their effect on virus resistance in nontransgenic sweet cherry. Plant Biotechnol J. 2014;12:1319–1328. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rajagopalan R, Vaucheret H, Trejo J, Bartel DP. A diverse and evolutionarily fluid set of microRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Gene Dev. 2006;20:3407–3425. doi: 10.1101/gad.1476406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiang, L.Y. Utilization of CRISPR/Cas9 to build plant virus resistant system of strawberry vein banding virus. http://kreader.cnki.net/Kreader/CatalogViewPage.aspx?dbCode=cdmd&filename=1017012102.nh&tablename=CMFD201701&compose=&first=1&uid=WEEvREdxOWJmbC9oM1NjYkZCbDZZNXlHdnlVcW1VMHRTcTFCeXREaUZOeHo=$R1yZ0H6jyaa0en3RxVUd8df-oHi7XMMDo7mtKT6mSmEvTuk11l2gFA!! (2016).

- 53.Qian HM, et al. Variation of glucosinolates and quinone reductase activity among different varieties of Chinese kale and improvement of glucoraphanin by metabolic engineering. Food Chem1. 2015;68:321–326. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.07.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sheng XG, et al. An efficient shoot regeneration system and Agrobacterium-mediated transformation with codA gene in a doubled haploid line of Broccoli. Can J Plant Sci. 2016;96:1014–1020. doi: 10.1139/cjps-2016-0027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lei Y, et al. CRISPR-P: A web tool for synthetic single-guide RNA design of CRISPR-system in plants. Mol Plant. 2014;7:1494–1496. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssu044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Original image shows the PCR detection of the hygromycin-resistant gene for the estimation of transformation efficiency.