Abstract

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the world leading cause of dementia. Early detection of AD is essential for faster and more efficacious usage of therapeutics and preventive measures. Even though it is well known that one ε4 allele of apolipoprotein E gene increases the risk for sporadic AD five times, and that two ε4 alleles increase the risk 20 times, reliable genetic markers for AD are not yet available. Previous studies have shown that microtubule‐associated protein tau (MAPT) gene polymorphisms could be associated with increased risk for AD.

Methods

The present study included 113 AD patients and 53 patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), as well as nine healthy controls (HC) and 53 patients with other primary causes of dementia. The study assessed whether six MAPT haplotype‐tagging polymorphisms (rs1467967, rs242557, rs3785883, rs2471738, del–In9, and rs7521) and MAPT haplotypes are associated with AD pathology, as measured by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) AD biomarkers amyloid β1–42 (Aβ1–42), total tau (t‐tau), tau phosphorylated at epitopes 181 (p‐tau181), 199 (p‐tau199), and 231 (p‐tau231), and visinin‐like protein 1 (VILIP‐1).

Results

Significant increases in t‐tau and p‐tau CSF levels were found in patients with AG and AA MAPT rs1467967 genotype, CC MAPT rs2471738 genotype and in patients with H1H2 or H2H2 MAPT haplotype.

Conclusions

These results indicate that MAPT haplotype‐tagging polymorphisms and MAPT haplotypes should be further tested as potential genetic biomarkers of AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, biomarkers, cerebrospinal fluid, genetic predisposition to disease, single‐nucleotide polymorphism, tau proteins

1. INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common primary cause of dementia, is a complex disease with poorly understood etiology. The characteristic amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary changes seen in AD brains are frequently observed in other neurodegenerative diseases. As a consequence, many AD cases are misdiagnosed. One such autopsy‐confirmed series showed sensitivity of AD diagnosis to range from 70.9% to 87.3%, while specificity ranged from 44.3% to 70.8% (with controls as reference groups; Beach, Monsell, Phillips, & Kukull, 2012; Gay, Taylor, Hohl, Tolnay, & Staehelin, 2008; Joachim, Morris, & Selkoe, 1988). This creates substantial difficulties in interpretations of results obtained by different studies that include patients with probable AD. One possibility to avoid this problem would be to use intermediate quantitative traits (endophenotypes) rather than clinical diagnoses (case–control studies) as indices of AD pathology. Endophenotypes are any biomarkers that signal the presence of AD pathology. For example, for this study, we used core cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers of AD, such as amyloid β1–42 (Aβ1–42), total tau (t‐tau), and tau phosphorylated at epitope 181 (p‐tau181), and potential CSF biomarkers, such as tau phosphorylated at epitopes 199 (p‐tau199), and 231 (p‐tau231), and visinin‐like protein 1 (VILIP‐1) as endophenotypes. Aβ1–42 indicates the presence of senile plaques in the brain (Grimmer et al., 2009), t‐tau and VILIP‐1 are markers of neurodegeneration (Babić et al., 2014; Babić Leko, Borovečki, Dejanović, Hof, & Šimić, 2016), while p‐tau181, p‐tau199, and p‐tau231 reflect the presence of neurofibrillary tangles in the brain (Bürger et al., 2006). CSF core biomarkers (Aβ1–42, t‐tau, and p‐tau181) were previously used in genome‐wide association studies (GWAS) as endophenotypes for detection of AD risk genes (Cruchaga et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2011). In this study, we used these biomarkers to assess whether certain variants of microtubule‐associated protein tau (MAPT) gene were associated to their pathological levels in CSF. Although AD is not caused by mutations in the MAPT gene, previous studies demonstrated that CSF biomarkers of AD differ among patients with different MAPT genotypes (Compta et al., 2011; Kauwe et al., 2008). Besides comparing the levels of CSF biomarkers Aβ1–42, t‐tau, p‐tau181, p‐tau199, p‐tau231, and VILIP‐1 among patients with six different MAPT genotypes, we also analyzed the distribution of MAPT H1 and H2 haplotypes and their subhaplotypes in a Croatian patient cohort.

The majority of AD patients are late‐onset sporadic cases, whose heritability for the disease has been estimated to be as high as 58%–79% (Gatz et al., 2006). In addition to apolipoprotein E gene (APOE), more than 20 common loci have been associated with risk for sporadic AD, age at onset, and progression of cognitive decline, but reported genome‐wide significant loci do not account for all the estimated heritability and provide little information about underlying biological mechanisms (Šimić et al., 2016a, 2016b). Therefore, genetic studies like the present one, using intermediate quantitative traits (endophenotypes) such as biomarkers, greatly benefit from increased statistical power to identify variants that may not pass the stringent multiple test corrections in case–control studies.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Subjects

The study was conducted at Clinical Hospital Center Zagreb from August 2011 until June 2016. All patients signed informed consent form for lumbar puncture and for participation in this study. The consent forms were explained in details to the patients and their guardians/caregivers. The study included 116 female (F) and 112 male (M) subjects: 113 AD patients (60F/53M) and 53 mild cognitive impairment (MCI) patients (27F/26M), nine healthy controls (HC, 6F/3M) and 53 patients with other causes of dementia (22 with frontotemporal dementia [FTD, 11F/11M], 14 with vascular dementia [VaD, 6F/8M], seven with dementia with Lewy bodies [DLB, 2F/5M], four with nonspecific dementia [ND, 3F/1M], three with mixed dementia [AD+VaD, 3M], two with Parkinson’s disease [PD, 2 M], and one with corticobasal syndrome [CBS]), all recruited at the University Hospital Center, Zagreb (Table 1).

Table 1.

Levels of CSF protein biomarkers and demographic data

| Aβ1 – 42 (pg/ml) | Total tau (pg/ml) | p‐tau181 (pg/ml) | p‐tau199 (pg/ml) | p‐tau231 (U/ml) | VILIP‐1 (pg/ml) | MMSE | Age | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD (number of patients) | Median (25–75th percentile) | Mean ± SD (number of patients) | Median (25–75th percentile) | Mean ± SD (number of patients) | Median (25–75th percentile) | Mean ± SD (number of patients) | Median (25–75th percentile) | Mean ± SD (number of patients) | Median (25–75th percentile) | Mean ± SD (number of patients) | Median (25–75th percentile) | Mean ± SD (number of patients) | Median (25–75th percentile) | |

| AD | 539.39 ± 298.92 (113) | 505.51 (308–725.5) | 507.45 ± 372.53 (113) | 507.45 (246.5–652.83) | 79.88 ± 47.96 (112) | 70.94 (55.25–93.65) | 4.37 ± 3.53 (113) | 3.56 (1.72–6.19) | 3.86 ± 5.52 (111) | 1.74 (0.67–3.72) | 137.12 ± 88.58 (111) | 121.73 (57.57–194.87) | 19.83 ± 4.85 (113) | 73 (67–77) |

| MCI | 723.44 ± 371.87 (53) | 679 (398.02–1,023) | 246.44 ± 158.00 (53) | 210 (134.5–330.17) | 57.64 ± 30.86 (51) | 51.96 (36.37–69.08) | 3.40 ± 2.35 (52) | 2.92 (1.37–5.21) | 1.82 ± 3.18 (51) | 0.82 (0.36–1.94) | 94.86 ± 78.11 (50) | 70.12 (27–135.04) | 25.09 ± 2.96 (53) | 70 (59–74) |

| HC | 860.33 ± 497.46 (9) | 1,022 (265–1,315) | 293.33 ± 346.14 (9) | 228 (62–367) | 48.54 ± 26.14 (9) | 55.82 (17.22–70.18) | 1.42 ± 0.96 (9) | 1.42 (0.72–2.42) | 1.29 ± 2.05 (9) | 0.51 (1.67–1.70) | 99.27 ± 70.36 (9) | 109.25 (27–160.30) | 27.43 ± 1.81 (9) | 52 (43–62) |

| FTD | 391.17 ± 175.17 (22) | 381.5 (276.78–532.1) | 502.02 ± 408.99 (22) | 322.02 (201.45–773.57) | 69.62 ± 37.89 (22) | 71.44 (31.76–106.81) | 5.92 ± 5.52 (22) | 4.34 (2.31–7.29) | 1.91 ± 2.34 (22) | 1.05 (0.69–1.93) | 104.21 ± 73.30 (22) | 77.29 (39.95–174.94) | 16.32 ± 5.31 (22) | 61 (56–65) |

| VaD | 502.91 ± 235.95 (14) | 432.13 (364.25–714.7) | 516.31 ± 325.75 (14) | 409.53 (310.73–742.47) | 72.68 ± 36.22 (13) | 72.9 (45.59–111.18) | 5.30 ± 5.51 (14) | 2.89 (1.60–7.89) | 1.44 ± 0.78 (13) | 1.54 (0.79–2.06) | 123.03 ± 78.30 (13) | 105.64 (47.04–173.57) | 23.50 ± 5.04 (14) | 71 (63–77) |

| DLB | 428.32 ± 259.78 (7) | 296.13 (200.68–657.11) | 126.41 ± 44.91 (7) | 130.03 (81.09–153.00) | 41.99 ± 28.84 (7) | 34.24 (25.79–39.98) | 2.48 ± 1.58 (7) | 2.58 (0.89–3.67) | 0.56 ± 0.18 (7) | 0.57 (0.48–0.67) | 47.80 ± 16.90 (7) | 48.02 (29.22–64.23) | 19.29 ± 3.90 (7) | 70 (68–75) |

| AD + VaD | 553.23 ± 37.17 (3) | 535 | 579.67 ± 460.42 (3) | 661 | 74.11 ± 28.57 (3) | 89.49 | 2.84 ± 1.93 (3) | 3.75 | 1.97 ± 1.80 (3) | 2.12 | 108.03 ± 70.19 (3) | 146.88 | 19.33 ± 4.04 (3) | 78 |

| ND | 459.46 ± 194.13 (4) | 465.31 (273.27–639.80) | 230.68 ± 116.96 (4) | 239.30 (118.96–333.78) | 25.48 ± 8.22 (4) | 26.49 (17.19–32.77) | 1.66 ± 1.94 (4) | 1.48 (0.00–3.50) | 0.39 ± 0.27 (4) | 0.42 (0.41–0.63) | 57.26 ± 60.52 (4) | 27 (27–117.78) | 19.25 ± 5.32 (4) | 66 (52–68) |

| PD | 232.08 ± 139.89 (2) | 282.08 | 30.5 ± 43.13 (2) | 30.5 | 20.48 ± 16.33 (2) | 20.48 | 1.26 ± 1.31 (2) | 1.26 | 0.35 ± 0.31 (2) | 0.35 | 27 (2) | 27 | 30 (1) | 78 |

| CBS | 917.56 (1) | 578.28 (1) | 84.3 (1) | 1.66 (1) | 0.81 (1) | 347.62 (1) | 27 (1) | 51 | ||||||

Aβ1–42: amyloid β1–42 protein; AD: Alzheimer's disease; AD + VaD: mixed dementia; CBS: corticobasal syndrome; DLB: dementia with Lewy bodies; FTD: frontotemporal dementia; HC: healthy control; MCI: mild cognitive impairment; ND: nonspecific dementia; p‐tau181: tau protein phosphorylated at threonine 181; p‐tau231: tau protein phosphorylated at threonine 231; p‐tau199: tau protein phosphorylated at serine 199; PD: Parkinson’s disease; SD: standard deviation; VaD: vascular dementia.

This research study had a diagnostic purpose exclusively and was not designed to evaluate any health‐related interventions or possible effects on health outcomes. Therefore, it was not registered as a clinical trial. All patients were neuropsychologically tested using the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), and Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale‐cognitive subscale (ADAS‐Cog), underwent neurological examination and complete blood tests including levels of vitamin B12, folic acid (B9), and thyroid function test, and had a negative serology for syphilis or Lyme’s disease. All procedures were approved by the Ethical Committee of the Clinical Hospital Center Zagreb and by the Central Ethical Committee of the University of Zagreb Medical School (case no. 380‐59/11‐500‐77/90, class 641‐01/11‐02), and were in accord with the Helsinki Declaration (World Medical Association, 2013).

For AD, we used diagnostic criteria of McKhann et al. (2011), while MCI was diagnosed according to Petersen et al. (1999) and Albert et al. (2011). For VaD, we used the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke—Association Internationale pour la Recherche et l'Enseignement en Neurosciences (NINCDS‐AIREN) criteria (Román et al., 1993), as well as the Hachinski Ischemic Score (HIS) (Hachinski et al., 1975). The most important clinical discriminative factors for VaD vs. AD are stepwise progression, prominent impairment of the executive functions, higher probability of VaD when HIS is >4, and focal neurological signs implying cortical or subcortical lesions (Desmond et al., 1999). Clinical criteria for FTD were based on consensus published by Neary and collaborators (Neary et al., 1998). Conditions overlapping AD are very difficult to study, but biomarkers that we have chosen are again superior in this respect in comparison to other approaches, such as correlation with clinical diagnosis.

2.2. Lumbar puncture and ELISA analysis of CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid was taken by lumbar puncture between intervertebral spaces L3/L4 or L4/L5. After centrifugation at 2,000 g for 10 min, CSF samples were aliquoted and stored in polypropylene tubes at −80°C. Levels of Aβ1–42, t‐tau, p‐tau231, p‐tau199, p‐tau181, and VILIP‐1 were determined using the following enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA): Aβ1–42 (Innotest β‐amyloid1–42, Fujirebio, Gent, Belgium), t‐tau (Innotest hTau Ag, Fujirebio), p‐tau231 (Tau [pT231] Phospho‐ELISA Kit, Human, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), p‐tau199 (TAU [pS199] Phospho‐ELISA Kit, Human, Thermo Fisher Scientific), p‐tau181 (Innotest Phospho‐Tau (181P), Fujirebio), and VILIP‐1 (VILIP‐1 Human ELISA, BioVendor, Brno, Czech Republic), respectively. Each CSF sample was analyzed in duplicate. Concentrations ranges of each biomarker are listed in Table 1. Cutoff values of CSF biomarkers were determined by ROC (receiver operating characteristic) curve analysis.

2.3. DNA analysis of MAPT polymorphisms

Venous blood samples (4 ml) were collected into plastic syringes with 1 ml of acid citrate dextrose as an anticoagulant. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood using the salting‐out method (Miller, Dykes, & Polesky, 1988). MAPT gene polymorphisms (rs1467967, rs242557, rs3785883, rs2471738, del–In9, and rs7521) were determined using primers and probes purchased from Applied Biosystems as TaqMan® SNP Genotyping Assay by ABI Prism 7300 Real Time PCR System apparatus (Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA). The del‐In9 deletion in MAPT Intron 9 defines the H1/H2 MAPT haplotype division caused by the inversion. H1 and H2 MAPT subhaplotypes were determined using haplotype tagging SNPs in following order: rs1467967, rs242557, rs3785883, rs2471738, del–In9, and rs7521 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of H1 and H2 MAPT subhaplotypes in the present cohort

| Subhaplotypes | htSNP alleles | Number of alleles | Percentage (%) of alleles |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1B | GGGCAA | 92 | 19.83 |

| H1c | AAGTAG | 58 | 12.50 |

| H1E | AGGCAA | 43 | 9.27 |

| H1D | AAGCAA | 37 | 7.97 |

| H1l | AGACAG | 30 | 6.47 |

| H1u | AAGCAG | 17 | 3.66 |

| H1h | AGACAA | 12 | 2.59 |

| H1i | GAGCAA | 10 | 2.16 |

| H1J | AGGCAG | 10 | 2.16 |

| H1m | GAGCAG | 10 | 2.16 |

| H1T | AGATAG | 10 | 2.16 |

| H1k | AAATAG | 9 | 1.94 |

| H1jj | GGGCAG | 8 | 1.72 |

| H1o | AAACAA | 8 | 1.72 |

| H1v | GGATAG | 7 | 1.51 |

| H1q | AAGTAA | 6 | 1.29 |

| H1g | GAACAA | 5 | 1.08 |

| H1x | GAATAG | 5 | 1.08 |

| H1y | GAACAG | 5 | 1.08 |

| H1F | GGACAA | 4 | 0.86 |

| H1p | GGGTAG | 3 | 0.65 |

| H1aa | GAGTAG | 2 | 0.43 |

| H1r | AGGTAG | 1 | 0.22 |

| H2A | AGGCGG | 56 | 12.07 |

| H2gg | AGACGG | 12 | 2.59 |

| H2ff | AAGCGG | 2 | 0.43 |

| H2kk | AGGCGA | 1 | 0.22 |

| H2w | GGGCGA | 1 | 0.22 |

2.4. Experimental design and statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in SPSS 19.0.1 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) with the statistical significance level set at α = 0.05. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used for assessing data distribution normality. Regardless of the results of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for normality, due to the small number of patients in certain groups, nonparametric tests (Kruskal–Wallis test and Mann–Whitney U test) were used for comparison of the biomarkers’ levels between groups of subjects with different MAPT genotypes and haplotypes. After Kruskal–Wallis test for pairwise comparisons of independent samples, we performed the post hoc analysis. Since this post hoc testing option in SPSS incorporates calculation of the corrected p‐value, there was no need for additional corrections due to multiple comparisons. Nevertheless, due to the relatively small sample size, we performed statistical analysis with and without outliers. Only one statistically significant difference was lost after exclusion of outliers. Only results of the statistical analysis without outliers are presented here.

2.5. Ethical approval

The present study was conducted according to the 6th revised Declaration of Helsinki (Edinburgh, 2000) and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and was approved by the local ethics committee of the Clinical Hospital Centre Zagreb. All the patients signed informed consent form for lumbar puncture, genetic research and for participation in this study. The consent form was explained in details to the patients and their legal guardians/caregivers. All procedures were approved by the Central Ethical Committee of the University of Zagreb Medical School (case no. 380‐59/11‐500‐77/90, class 641‐01/11‐02, signed on 19 May 2011).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Comparison of protein CSF biomarkers between subjects with different MAPT genotypes

The concentrations of CSF protein biomarkers (Aβ1–42, t‐tau, p‐tau181, p‐tau199, p‐tau231, and VILIP‐1) in the analyzed subjects are presented in Table 1. The measured interassay coefficient of variability (CV) was <10%. The intraassay CV was <15% for all biomarkers used. No significant differences were found between males and females in any of the groups. There was no significant difference in the levels of CSF protein biomarkers among subjects with different MAPT rs242557, MAPT rs3785883, and MAPT rs7521 genotypes.

3.2. MAPT rs1467967 genotype

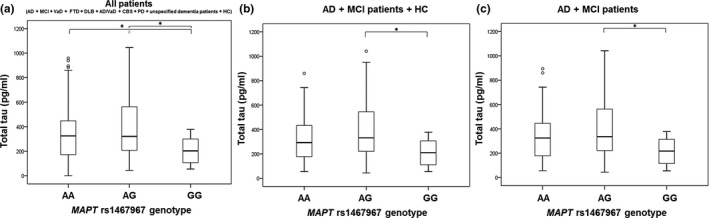

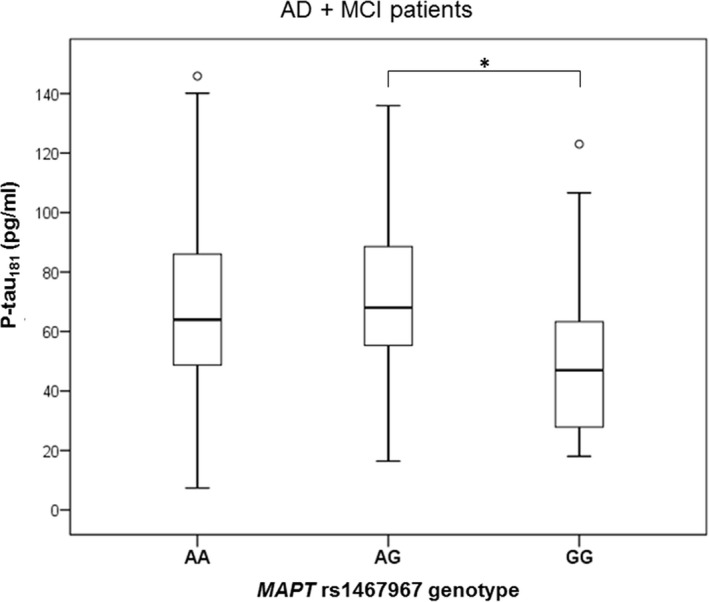

The difference in t‐tau levels was detected between patients with MAPT rs1467967 genotype (H = 11.655, df = 2, p = 0.003). T‐tau levels were significantly higher in patients with AG compared to GG MAPT rs1467967 genotype (p = 0.002) and AA compared to GG MAPT rs1467967 genotype (p = 0.022) when all patients were analyzed together (Figure 1a). The observation of increased t‐tau levels in patients with AG compared to GG MAPT rs1467967 genotype was confirmed when combining AD and MCI patients, and healthy controls (p = 0.004; Figure 1b) and in AD and MCI patients (p = 0.005; Figure 1c). The difference in p‐tau181 levels was detected between patients with MAPT rs1467967 genotype (H = 6.955, df = 2, p = 0.031). P‐tau181 levels were significantly higher in patients with AG in comparison to GG MAPT rs1467967 genotype when combining AD and MCI patients (p = 0.025; Figure 2). There was no significant difference in levels of Aβ1–42, p‐tau199, p‐tau231, and VILIP‐1 among subjects with different MAPT rs1467967 genotype.

Figure 1.

Levels of t‐tau in (a) all patients, (b) AD, MCI patients and HC, and (c) AD and MCI patients with MAPT rs1467967 genotype. Boxes represent the median, the 25th and 75th percentiles, and bars indicate the range of data distribution. Circles represent outliers. *p < 0.05

Figure 2.

Levels of p‐tau181 in AD and MCI patients with MAPT rs1467967 genotype. Boxes represent the median, the 25th and 75th percentiles, and bars indicate the range of data distribution. Circles represent outliers. *p < 0.05

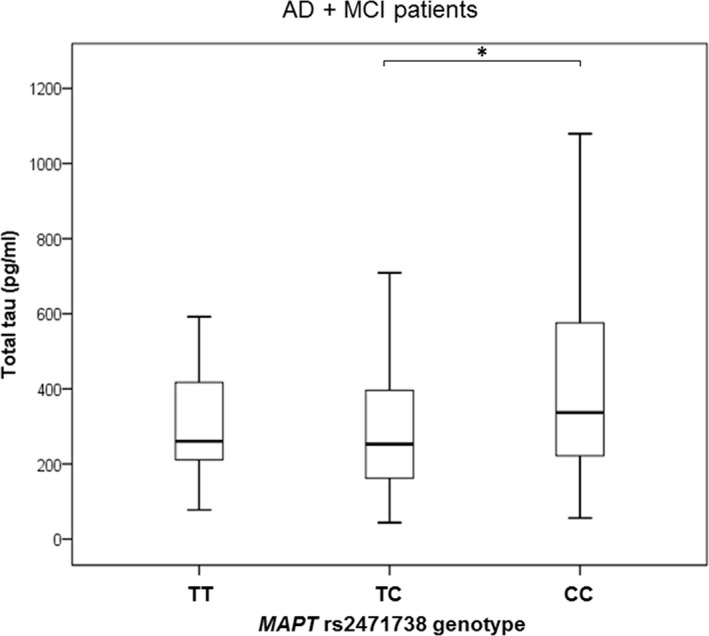

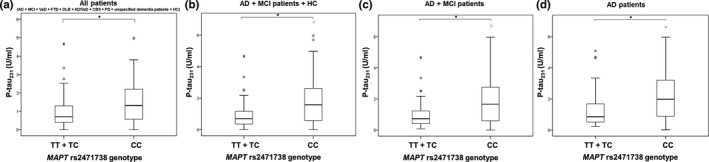

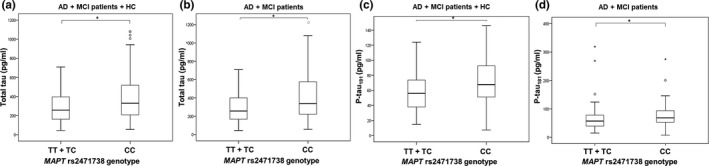

3.3. MAPT rs2471738 genotype

The difference in t‐tau levels was detected between patients with MAPT rs2471738 genotype (H = 8.042, df = 2, p = 0.018). More precisely, t‐tau levels were significantly higher in subjects with CC in comparison to TC MAPT rs2471738 genotype (in AD and MCI patients; p = 0.017; Figure 3). Levels of p‐tau231 were significantly higher in subjects with CC compared to TT + TC MAPT rs2471738 genotype (in all patients grouped together; U = 3,206, Z = −3.621, p < 0.001; Figure 4a), in the combined group of AD, MCI patients and healthy controls (U = 1613.5, Z = −3.993, p < 0.001; Figure 4b), in AD and MCI patients (U = 1,467, Z = −3.794, p < 0.001; Figure 4c) and in AD patients (U = 671, Z = −3.000, p = 0.003; Figure 4d). T‐tau levels were significantly higher in subjects with CC in comparison to TT + TC MAPT rs2471738 genotype (combining AD, MCI patients and healthy controls; U = 2,462.5, Z = −2.497, p = 0.013; Figure 5a), and in AD and MCI patients (U = 2,148, Z = −2.823, p = 0.005; Figure 5b). P‐tau181 levels were significantly higher in subjects with CC in comparison to TT + TC MAPT rs2471738 genotype (combining AD, MCI patients and healthy controls; U = 2,485, Z = −2.689, p = 0.007; Figure 5c), and in AD and MCI patients (U = 2,411, Z = −2.534, p = 0.011; Figure 5d). There was no significant difference in levels of Aβ1–42, p‐tau199, and VILIP‐1 among subjects with different MAPT rs2471738 genotype.

Figure 3.

Levels of t‐tau in AD and MCI patients with MAPT rs2471738 genotype. Boxes represent the median, the 25th and 75th percentiles, and bars indicate the range of data distribution. Circles represent outliers. *p < 0.05

Figure 4.

Levels of p‐tau231 in (a) all patients, (b) AD, MCI patients and HC, (c) AD and MCI patients, and (d) AD patients with the MAPT rs2471738 genotype. Boxes represent the median, the 25th and 75th percentiles, and bars indicate the range of data distribution. Circles represent outliers, and asterisks represent extreme data points. *p < 0.05

Figure 5.

Levels of t‐tau (a, b) and p‐tau181 (c, d) in AD, MCI patients and HC and in AD and MCI patients with the MAPT rs2471738 genotype. Boxes represent the median, the 25th and 75th percentiles, and bars indicate the range of data distribution. Circles represent outliers, and asterisks represent extreme data points. *p < 0.05

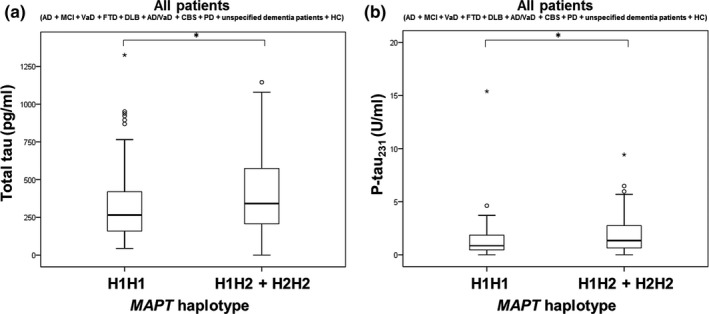

3.4. MAPT haplotypes

In this Croatian cohort, 23 H1 subhaplotypes and 5 H2 subhaplotypes were detected (Table 2). T‐tau (U = 3,791, Z = −2.524, p = 0.012; Figure 6a) and p‐tau231 (U = 3,124.5, Z = −2.710, p = 0.007; Figure 6b) levels were significantly higher in subjects with H1H2 + H2H2 haplotype compared to H1H1 haplotype when all patients were analyzed together.

Figure 6.

Levels of (a) t‐tau and (b) p‐tau231 in all patients with H1H1 and H1H2 + H2H2 MAPT haplotypes. Boxes represent the median, the 25th and 75th percentiles, and bars indicate the range of data distribution. Circles represent outliers, and asterisks represent extreme data points. *p < 0.05

4. DISCUSSION

This preliminary study of a Croatian cohort investigated whether certain variants of MAPT gene were associated with AD pathology as it was shown that polymorphisms in the MAPT gene increase the risk of tauopathies (Di Maria et al., 2010; Myers et al., 2005; Pittman et al., 2005). While a limitation of this study is a low number of HC (n = 9), our analysis of MAPT polymorphisms was conducted in all patients including the HC group (228 subjects in total), as such, the small number of HC is unlikely to have influenced the outcome of the analysis. The levels of t‐tau and p‐tau181 were significantly higher in patients with AG compared to GG MAPT rs1467967 genotype. Levels of t‐tau were significantly higher in patients with AA compared to GG MAPT rs1467967 genotype. Levels of t‐tau were significantly higher in patients with CC compared to TC MAPT rs2471738 genotype. Additionally, levels of t‐tau, p‐tau181 and p‐tau231 were significantly higher in patients with CC compared to patients with TT or TC MAPT rs2471738 genotypes. Also, levels of t‐tau and p‐tau231 were significantly higher in patients with H1H2 or H2H2 haplotypes compared to patients with the H1H1 haplotype.

Previous studies reported significant differences in CSF tau levels in carriers of risk alleles in MAPT rs242557 (Compta et al., 2011; Laws et al., 2007), rs16940758, rs3785883, rs243511, and rs2471738 polymorphisms (Kauwe et al., 2008). Additionally, Chen et al. (2017) found an association of the A‐allele in MAPT rs242557 polymorphism with increased levels of t‐tau in plasma. Compta and collaborators found that carriers of the A‐allele in MAPT rs242557 polymorphism had increases in CSF t‐tau and p‐tau181 levels (Compta et al., 2011). This was observed in patients with PD, but only in those with dementia and pathological Aβ1–42 levels (lower than 500 pg/ml). Although Compta et al. compared the levels of t‐tau and p‐tau181 in PD patients with different MAPT rs1880753, rs1880756, rs1800547, rs1467067, rs242557, rs2471738, and rs7521 genotypes, they found no significant differences in t‐tau and p‐tau181 levels in contrast to the present study that reveals t‐tau and p‐tau levels to be altered in patients with different MAPT rs1467967 and rs2471738 genotypes. Elias‐Sonnenschein et al. (2013) tested if different MAPT rs1467967 and rs7521 genotypes affected the levels of Aβ1–42, t‐tau and p‐tau181 in AD patients. No significant difference in the levels of CSF biomarkers between these patients was found. However, MAPT rs2435211 and rs16940758 polymorphisms were related to increased t‐tau and p‐tau, respectively. In the study of Kauwe et al. (2008) in which 21 SNPs in MAPT gene were genotyped, an association of rs16940758, rs3785883, rs243511, and rs2471738 with p‐tau181 was observed. Additionally, these polymorphisms demonstrated an association with t‐tau and p‐tau181 in patients with pathological Aβ1–42 levels. This study supports our finding that t‐tau, p‐tau181, and p‐tau231 levels are significantly different in patients with different MAPT rs2471738 genotypes. However, in contrast to our results, the association of MAPT rs1467967 genotype with t‐tau and p‐tau181 that was also tested in that study was not observed (Kauwe et al., 2008). Although Laws et al. (2007) analyzed the association of CSF t‐tau with all polymorphisms included in our study, only an association of MAPT rs242557 genotype with t‐tau levels was observed. Laws et al. proposed that association between CSF tau levels and MAPT polymorphisms (or haplotypes) could occur through MAPT expression. In other words, individuals carrying risk MAPT alleles have a higher MAPT brain expression and consequently an increased neurodegeneration and leakage of tau protein in CSF (Laws et al., 2007).

The study of Ning et al. (2011) showed that MAPT rs1467967 polymorphism could serve as a genetic biomarker for VaD, since the rs1467967 genotypes differed between VaD patients and HC. Also, the MAPT rs2471738 polymorphism was associated with an increased risk for AD (Vázquez‐Higuera et al., 2009). While the meta‐analysis of Yuan, Du, Ge, Wang, & Xia (2018) showed that none of the polymorphisms analyzed in the present study (rs1467967, rs3785883, rs2471738, and rs7521), except for rs242557 that showed an association with AD, the meta‐analysis of Zhou and Wang (2017) demonstrated an association of rs242557 and rs2471738 polymorphisms (but not rs3785883 or rs1467967 polymorphisms) with AD.

The association of the H1U and H1H haplotypes and H1C haplotype with t‐tau levels was previously demonstrated (Kauwe et al., 2008; Laws et al., 2007). The H1C haplotype was shown to be a risk factor for progressive supranuclear palsy and CBS (Pittman et al., 2005), late‐onset AD (LOAD; Myers et al., 2005), and MCI (Di Maria et al., 2010), while the H2 haplotype was associated with a reduced risk for LOAD (Allen et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2017). Our results do not support observations that individuals with the H1 haplotype have increased CSF t‐tau levels (Kauwe et al., 2008; Laws et al., 2007) and increased risk for AD or other tauopathies (Di Maria et al., 2010; Myers et al., 2005; Pittman et al., 2005), as our patients with the H2 haplotype had pathological CSF t‐tau and p‐tau levels. However, several studies failed to detect the association of the H1 haplotype with an increased risk for AD (Abraham et al., 2009; Mukherjee, Kauwe, Mayo, Morris, & Goate, 2007; Russ et al., 2001). Additionally, in the study of Min et al. (2014), patients with FTD and MAPT H1 haplotype had an increase in CSF p‐tau181 levels, while there was no difference in the levels of t‐tau. Another study found no association between MAPT haplotypes and CSF t‐tau, p‐tau181 or Aβ1–42 levels (Johansson, Zetterberg, Håkansson, Nissbrandt, & Blennow, 2005).

In conclusion, the present study resulted in several notable findings. The association of MAPT rs1467967 polymorphism with AD pathology measured by levels of CSF biomarkers was demonstrated, with CSF t‐tau and p‐tau181 levels being significantly higher in patients with AG compared to GG MAPT rs1467967 genotype and t‐tau levels being significantly higher in patients with AA compared to GG MAPT rs1467967 genotype. Additionally, we detected an association of the MAPT rs2471738 polymorphism with AD pathology that was also observed in previous studies (Kauwe et al., 2008; Vázquez‐Higuera et al., 2009). However, the MAPT rs2471738 risk allele detected in our study (C‐allele) differs from the risk allele detected in the study of Myers et al. (2005) and Vázquez‐Higuera et al. (2009) (T‐allele), warranting further investigation. We also observed an increase in CSF t‐tau and p‐tau levels in patients with H1H2 or H2H2 haplotypes. This finding differs from studies in which the H1 haplotype was detected as a risk haplotype for AD and other tauopathies (Di Maria et al., 2010; Myers et al., 2005), and this issue also will require additional research. We used potentially novel CSF biomarkers of AD as endophenotypes (p‐tau199, p‐tau231, and VILIP‐1), while previous studies testing the association of MAPT polymorphisms with AD used only core CSF biomarkers as endophenotypes (Aβ1–42, t‐tau, p‐tau181). The p‐tau231 endophenotype showed significant difference between groups of patients with different MAPT genotypes. Finally, we detected 23 H1 and 5 H2 MAPT subhaplotypes in this Croatian cohort, revealing that MAPT haplotype‐tagging polymorphisms and MAPT haplotypes should be further tested as potential genetic biomarkers of AD.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

GŠ conceived and directed the study. NK and FB performed the clinical assessments and lumbar puncture. NW and RdS determined MAPT haplotypes. MNP and NP determined MAPT genotypes. MBL and GŠ determined levels of CSF biomarkers. MBL, ZS and GŠ completed statistical analysis. PRH substantially contributed to the interpretation of data and to manuscript preparation. All authors contributed to revising and editing the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors met the criteria for authorship, as defined by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

Babić Leko M, Willumsen N, Nikolac Perković M, et al. Association of MAPT haplotype‐tagging polymorphisms with cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease: A preliminary study in a Croatian cohort. Brain Behav. 2018;8:e01128 10.1002/brb3.1128

Funding information

This work was funded by The Croatian Science Foundation grant IP‐2014‐09‐9730 (“Tau protein hyperphosphorylation, aggregation, and trans‐synaptic transfer in Alzheimer’s disease: cerebrospinal fluid analysis and assessment of potential neuroprotective compounds”) and by the European Union through the European Regional Development Fund, Operational Programme Competitiveness and Cohesion, grant agreement no. KK.01.1.1.01.0007, CoRE—Neuro, and in part by NIH grant P50 AG005138 to PRH.

REFERENCES

- Abraham, R. , Sims, R. , Carroll, L. , Hollingworth, P. , O’Donovan, M. C. , Williams, J. , & Owen, M. J. (2009). An association study of common variation at the MAPT locus with late‐onset Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics, 150B(8), 1152–1155. 10.1002/ajmg.b.30951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert, M. S. , DeKosky, S. T. , Dickson, D. , Dubois, B. , Feldman, H. H. , Fox, N. C. , Phelps, C. H. (2011). The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging‐Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer’s and Dementia, 7(3), 270–279. 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen, M. , Kachadoorian, M. , Quicksall, Z. , Zou, F. , Chai, H. , Younkin, C. , Ertekin‐Taner, N. (2014). Association of MAPT haplotypes with Alzheimer’s disease risk and MAPT brain gene expression levels. Alzheimer’s Research and Therapy, 6(4), 39 10.1186/alzrt268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babić Leko, M. , Borovečki, F. , Dejanović, N. , Hof, P. R. , & Šimić, G. (2016). Predictive value of cerebrospinal fluid visinin‐like protein‐1 levels for Alzheimer’s disease early detection and differential diagnosis in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 50, 765–778. 10.3233/JAD-150705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babić, M. , Švob Štrac, D. , Mück‐Šeler, D. , Pivac, N. , Stanić, G. , Hof, P. R. , & Šimić, G. (2014). Update on the core and developing cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer disease. Croatian Medical Journal, 55(4), 347–365. 10.3325/cmj.2014.55.347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach, T. G. , Monsell, S. E. , Phillips, L. E. , & Kukull, W. (2012). Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease at National Institute on Aging Alzheimer Disease Centers, 2005–2010. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology, 71(4), 266–273. 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31824b211b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bürger, K. , Ewers, M. , Pirttila, T. , Zinkowski, R. , Alafuzoff, I. , Teipel, S. J. , Hampel, H. (2006). CSF phosphorylated tau protein correlates with neocortical neurofibrillary pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain, 129(11), 3035–3041. 10.1093/brain/awl269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. , Yu, J.‐T. , Wojta, K. , Wang, H.‐F. , Zetterberg, H. , Blennow, K. , … Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2017). Genome‐wide association study identifies MAPT locus influencing human plasma tau levels. Neurology, 88(7), 669–676. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compta, Y. , Ezquerra, M. , Muñoz, E. , Tolosa, E. , Valldeoriola, F. , Rios, J. , Marti, M. J. (2011). High cerebrospinal tau levels are associated with the rs242557 tau gene variant and low cerebrospinal β‐amyloid in Parkinson disease. Neuroscience Letters, 487(2), 169–173. 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruchaga, C. , Kauwe, J. S. K. , Harari, O. , Jin, S. C. , Cai, Y. , Karch, C. M. , Goate, A. M. (2013). GWAS of cerebrospinal fluid tau levels identifies risk variants for Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron, 78(2), 256–268. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.02.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond, D. , Erkinjuntti, T. , Sano, M. , Cummings, J. , Bowler, J. , & Pasquier, F. (1999). The cognitive syndrome of vascular dementia: Implications for clinical trials. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 13, 21–29. 10.1097/00002093-199912001-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Maria, E. , Cammarata, S. , Parodi, M. I. , Borghi, R. , Benussi, L. , Galli, M. , Tabaton, M. (2010). The H1 haplotype of the tau gene (MAPT) is associated with mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 19(3), 909–914. 10.3233/JAD-2010-1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias‐Sonnenschein, L. S. , Helisalmi, S. , Natunen, T. , Hall, A. , Paajanen, T. , Herukka, S.‐K. , Hiltunen, M. (2013). Genetic loci associated with Alzheimer’s disease and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in a Finnish case‐control cohort. PLoS ONE, 8(4), e59676 10.1371/journal.pone.0059676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatz, M. , Reynolds, C. A. , Fratiglioni, L. , Johansson, B. , Mortimer, J. A. , Berg, S. , Pedersen, N. L. (2006). Role of genes and environments for explaining Alzheimer disease. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(2), 168 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay, B. E. , Taylor, K. I. , Hohl, U. , Tolnay, M. , & Staehelin, H. B. (2008). The validity of clinical diagnoses of dementia in a group of consecutively autopsied memory clinic patients. Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging, 12(2), 132–137. 10.1007/BF02982566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimmer, T. , Riemenschneider, M. , Förstl, H. , Henriksen, G. , Klunk, W. E. , Mathis, C. A. , Drzezga, A. (2009). Beta amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease: Increased deposition in brain is reflected in reduced concentration in cerebrospinal fluid. Biological Psychiatry, 65(11), 927–934. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hachinski, V. C. , Iliff, L. D. , Zilhka, E. , Du Boulay, G. H. , McAllister, V. L. , Marshall, J. , Symon, L. (1975). Cerebral blood flow in dementia. Archives of Neurology, 32(9), 632–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joachim, C. L. , Morris, J. H. , & Selkoe, D. J. (1988). Clinically diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease: Autopsy results in 150 cases. Annals of Neurology, 24(1), 50–56. 10.1002/ana.410240110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, A. , Zetterberg, H. , Håkansson, A. , Nissbrandt, H. , & Blennow, K. (2005). TAU haplotype and the Saitohin Q7R gene polymorphism do not influence CSF Tau in Alzheimer’s disease and are not associated with frontotemporal dementia or Parkinson's disease. Neurodegenerative Diseases, 2(1), 28–35. 10.1159/000086428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauwe, J. S. K. , Cruchaga, C. , Mayo, K. , Fenoglio, C. , Bertelsen, S. , Nowotny, P. , Goate, A. M. (2008). Variation in MAPT is associated with cerebrospinal fluid tau levels in the presence of amyloid‐beta deposition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(23), 8050–8054. 10.1073/pnas.0801227105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. , Swaminathan, S. , Shen, L. , Risacher, S. L. , Nho, K. , Foroud, T. , … Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2011). Genome‐wide association study of CSF biomarkers A 1–42, t‐tau, and p‐tau181p in the ADNI cohort. Neurology, 76(1), 69–79. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318204a397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laws, S. M. , Friedrich, P. , Diehl‐Schmid, J. , Müller, J. , Eisele, T. , Bäuml, J. , Riemenschneider, M. (2007). Fine mapping of the MAPT locus using quantitative trait analysis identifies possible causal variants in Alzheimer’s disease. Molecular Psychiatry, 12(5), 510–517. 10.1038/sj.mp.4001935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann, G. , Knopman, D. S. , Chertkow, H. , Hymann, B. , Jack, C. R. , Kawas, C. , Phelphs, C. (2011). The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging‐ Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dementia, 7(3), 263–269. 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S. A. , Dykes, D. D. , & Polesky, H. F. (1988). A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Research, 16(3), 1215 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min, N. E. , McMillan, C. , Irwin, D. , Lee, V. , Trojanowski, J. , Van Deerlin, V. , & Grossman, M. (2014). Association of the MAPT with cerebrospinal fluid phosphorylated tau levels in frontotemporal degeneration. Neurology, 82(10), S38.008. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, O. , Kauwe, J. S. , Mayo, K. , Morris, J. C. , & Goate, A. M. (2007). Haplotype‐based association analysis of the MAPT locus in late onset Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Genetics, 8(1), 3 10.1186/1471-2156-8-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers, A. J. , Kaleem, M. , Marlowe, L. , Pittman, A. M. , Lees, A. J. , Fung, H. C. , Hardy, J. (2005). The H1c haplotype at the MAPT locus is associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Human Molecular Genetics, 14(16), 2399–2404. 10.1093/hmg/ddi241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neary, D. , Snowden, J. S. , Gustafson, L. , Passant, U. , Stuss, D. , Black, S. , Benson, D. F. (1998). Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: A consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology, 51(6), 1546–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning, M. , Zhang, Z. , Chen, Z. , Zhao, T. , Zhang, D. , Zhou, D. , He, L. (2011). Genetic evidence that vascular dementia is related to Alzheimer’s disease: Genetic association between tau polymorphism and vascular dementia in the Chinese population. Age and Ageing, 40(1), 125–128. 10.1093/ageing/afq131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, R. C. , Smith, G. E. , Waring, S. C. , Ivnik, R. J. , Tangalos, E. G. , & Kokmen, E. (1999). Mild cognitive impairment: Clinical characterization and outcome. Archives of Neurology, 56(3), 303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman, A. M. , Myers, A. J. , Abou‐Sleiman, P. , Fung, H. C. , Kaleem, M. , Marlowe, L. , de Silva, R. (2005). Linkage disequilibrium fine mapping and haplotype association analysis of the tau gene in progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration. Journal of Medical Genetics, 42(11), 837–846. 10.1136/jmg.2005.031377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Román, G. C. , Tatemichi, T. K. , Erkinjuntti, T. , Cummings, J. L. , Masdeu, J. C. , Garcia, J. H. , Scheinberg, P. (1993). Vascular dementia. Neurology, 43(2), 250–260. 10.1212/WNL.43.2.250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russ, C. , Powell, J. F. , Zhao, J. , Baker, M. , Hutton, M. , Crawford, F. , Lovestone, S. (2001). The microtubule associated protein Tau gene and Alzheimer’s disease–an association study and meta‐analysis. Neuroscience Letters, 314(1–2), 92–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šimić, G. , Babić Leko, M. , Wray, S. , Harrington, C. , Delalle, I. , Jovanov‐Milošević, N. , … Hof, P. R. (2016a). Tau protein hyperphosphorylation and aggregation in Alzheimer’s disease and other tauopathies, and possible neuroprotective strategies. Biomolecules, 6(1), 6 10.3390/biom6010006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šimić, G. , Babić Leko, M. , Wray, S. , Harrington, C. R. , Delalle, I. , Jovanov‐Milošević, N. , … Hof, P. R. (2016b). Monoaminergic neuropathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Progress in Neurobiology, 151, 101–138. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2016.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez‐Higuera, J. L. , Mateo, I. , Sánchez‐Juan, P. , Rodríguez‐Rodríguez, E. , Pozueta, A. , Infante, J. , Combarros, O. (2009). Genetic interaction between tau and the apolipoprotein E receptor LRP1 Increases Alzheimer’s disease risk. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 28(2), 116–120. 10.1159/000234913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association . (2013). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310(20): 2191–2194. 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, H. , Du, L. , Ge, P. , Wang, X. , & Xia, Q. (2018). Association of microtubule‐associated protein tau gene polymorphisms with the risk of sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease: A meta‐analysis. International Journal of Neuroscience, 128(6), 577–585. 10.1080/00207454.2017.1400972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.‐C. , Zhu, J.‐X. , Wan, Y. , Tan, L. , Wang, H.‐F. , Yu, J.‐T. , & Tan, L. (2017). Meta‐analysis of the association between variants in MAPT and neurodegenerative diseases. Oncotarget, 8(27), 44994–45007. 10.18632/oncotarget.16690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F. , & Wang, T. (2017). The associations between the MAPT polymorphisms and Alzheimer’s disease risk: A meta‐analysis. Oncotarget, 8, 43506–43520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.