Abstract

An increasing body of evidence has indicated that spinal microglial Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) may serve a significant role in the development and maintenance of neuropathic pain (NP). In the present study, experiments were conducted to evaluate the contribution of a tetracycline inducible lentiviral-mediated delivery system for the expression of TLR4 small interfering (si)RNA to NP in rats with chronic constriction injury (CCI). Behavioral tests, including paw withdrawal latency and paw withdrawal threshold, and biochemical analysis of the spinal cord, including western blotting, reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction and ELISA, were conducted following CCI to the sciatic nerve. Intrathecal administration of LvOn-si-TLR4 with doxycycline (Dox) attenuated allodynia and hyperalgesia. Biochemical analysis revealed that the mRNA and proteins levels of TLR4 were unregulated following CCI to the sciatic nerve, which was then blocked by intrathecal administration of LvOn-siTLR4 with Dox. The LvOn-siTLR4 was also demonstrated to have no effect on TLR4 or the pain response without Dox, which indicated that the expression of siRNA was Dox-inducible in the lentivirus delivery system. In conclusion, TLR4 may serve a significant role in neuropathy and the results of the present study provide an inducible lentivirus-mediated siRNA against TLR4 that may serve as a potential novel strategy to be applied in gene therapy for NP in the future.

Keywords: Toll-like receptor 4, neuropathic pain, RNA interference, lentivirus, doxycycline

Introduction

Neuropathic pain (NP) is a complex, chronic pain state that is characterized by hyperalgesia, allodynia and spontaneous pain; it occurs as a consequence of mechanical nerve injury that can occur during the progression of cancer, multiple sclerosis and stroke (1). It is currently an important clinical problem that lacks an effective treatment. At present, the commonly used analgesics, especially opioid drugs, do not completely reduce symptoms of chronic pain and have various side effects, including respiratory depression, the development of drug tolerance and addiction (2). However, the broad range of receptors and signal transduction pathways that may be involved in this process provide a wealth of research opportunities. The current evidence has revealed that spinal microglia are critically involved in the development and maintenance of NP, with two members of the Toll-like receptor (TLR) family serving a pivotal role. For neuropathy, the most relevant region of TLR expression is on microglia (3). Therefore, a number of studies are investigating more effective and sustained treatments targeting the TLR family.

TLR4, a membrane-spanning receptor protein, is closely associated with chronic nociceptive responses in the central nervous system, as determined previously in animal models of NP (4,5). In pain-associated neuropathy mouse models, thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia were reduced by the administration of FP-1, a potent TLR4 antagonist (6). Furthermore, induced hypersensitivity has been reported to be decreased in TLR4 deficient mice (6). Therefore, blocking the TLR4 signaling pathway represents a potentially effective method for curing NP.

Based on previous studies, the availability of TLR4 receptor antagonists is non-specific. Furthermore, the increasing body of information on the RNA interference (RNAi) technique means it is now possible to precisely knockdown relevant genes (7,8). Therefore, it seems plausible to investigate a novel method for the treatment of NP by targeting the TLR4 receptor. It has been reported that downregulation of the GluN2B receptor by intrathecal injection of small interfering (si)RNA reduced formalin-induced nociception in rats, which supported the notion of treating NP using the RNAi technique (8). However, siRNA alone is unstable due to its tendency to degrade (9), therefore, a vector is required to express the siRNA. In the author's previous study, a lentivirus system was introduced as a tool for the expression of siRNA. The results revealed that intrathecal injection of the lentivirus-mediated siRNA against GluN2B reduced the nociception of NP rats for 5 weeks (10), which provided a vehicle for expressing siRNA in treating NP.

In the present study, a lentivirus system was introduced in order to express TLR4 siRNA. To control the timing and levels of target gene expression, a tetracycline inducible system was applied to regulate TLR4 expression. The anti-nociceptive effect of TLR4 siRNA under the regulation of doxycycline (Dox) was observed in a rat model of chronic constriction injury (CCI).

Materials and methods

Production of the LvOn-siTLR4 lentivirus

LvOn-siTLR4, a tetracycline inducible lentivirus expressing siRNA, was produced using 293T cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Red fluorescence protein (RFP), a reporter protein, was introduced into the lentiviral system in order to detect the number of lentiviruses and to trace the location of the virus. The siRNA (5′-GUCUCAGAUAUCUAGAUCU-3′) targeting the TLR4 receptor gene (GenBank accession NM_019178) was screened and tested as described in the author's previous study (9). Based on the sequences of the lentivirus and the principle of ‘Tuschl’, the inducible lentivirus LvOn-siTLR4 was produced as described previously (11) and was confirmed by an immunofluorescence assay for RFP under an Olympus fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) (9). Briefly, target sequences were chemically synthesized and were then cloned into plasmid pLenR-TRIP (Genomeditech, Shanghai, China) and named pLenR-TRIP-TLR4. To produce recombinant lentivirus LvOnsiTLR4 (lentivirus expressing the TLR4 siRNA), pRsv-REV (4,174 bp; 5.04 µg), pMDlg-pRRE (8,895 bp; 7.57 µg) and pMD2G (5,824 bp; 3.79 µg) were co-transfected into 293T cells (2–2.5×106) with Lipofectamine 2000™ (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). A total of ~48 h following transfection, the lentivirus was harvested, and activity measurement was performed following a further 24 h. The final titer of the virus was adjusted to 1×109 TU/ml.

Animals and CCI surgery

Male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats weighing 200–250 g (n=180; aged 6–7 weeks old) were obtained from the Shanghai Experimental Animal Center, The Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Animals were provided food and water ad libitum and housed at a temperature of 23–25°C) and 45–55% humidity, which was maintained on a 12/12 h light/dark cycle. All animal experiments were approved by the Administrative Committee of Experimental Animal Care and Use of the Second Military Medical University (Shanghai, China), and conformed to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1978). The CCI procedure was performed as described previously (12). The right sciatic nerve was exposed at the mid-thigh level following the rats were anesthetized with 40 mg/kg of sodium pentobarbital (intraperitoneal injection). The sciatic nerve was loosely ligated with 4-0 chromic gut threads at 4 sites, 1 mm apart, allowing the nerve diameter to reduce slightly. The sciatic nerve was exposed but not ligated in the sham group. The rats were then individually housed following recovery from anesthesia and monitored three times a day.

Lumbar subarachnoid catheterization

Chronic indwelling catheters were implanted in the lumbar subarachnoid space on the same day as the CCI surgery. A PE-10 catheter (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was carefully inserted into the subarachnoid space between lumbar vertebrae 5 (L5) and L6 (13). Successful implantation was confirmed by observing the tail-flick reflex and cerebrospinal fluid flow from the tip of the catheter. The external part of the catheter was protected according to the Milligan's method (14). A lidocaine test was performed to determine the position and functionality of the catheter in the subarachnoid space.

Intrathecal delivery of lentivirus

Rats were randomly divided into 6 groups (n=30 per group): A sham group [Sham surgery + normal saline (NS)], a CCI group (CCI surgery), an Lv-mismatch group (CCI + Lv-mismatch), an LvOn-siTLR4 group (CCI + LvOn-siTLR4 + NS), a Dox group (CCI + Dox) and an LvOn-siTLR4 with Dox group (CCI + LvOn-siTLR4 + Dox). The lentivirus Lv-mismatch expressing scrambled siRNA (TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT) was used as a control. Following CCI, rats in the LvOn-siTLR4 and LvOn-siTLR4 with Dox groups were administered the LvOn-siTLR4 virus (1×107 TU/10 µl) intrathecally. The same titer of Lv-mismatch was applied intrathecally to the Lv-mismatch group. NS of equal volume was administered intrathecally to the rats of the NS groups. In the Dox and LvOn-siTLR4 with Dox groups, Dox was given orally in water (200 ng/ml).

Evaluation of thermal hyperalgesia

Thermal hyperalgesia was evaluated by paw withdrawal latency (PWL) to radiant heat as previously described (15,16). PWL was measured one day prior to and 1, 3, 5 and 7 days following intrathecal administration of the lentivirus. Rats were placed in an inverted clear plexiglass cage (23×18×13 cm) on a 3-mm-thick glass plate for 30 min to acclimate to the surroundings. A radiant heat source consisting of a high-intensity projection lamp bulb was positioned under the glass floor beneath the right hind paw. The radiant heat source was placed 40 mm below the floor and projected through a 5×10 mm aperture at the top of a movable case. A digital timer automatically detected the time from stimuli to PWL. Detection was carried out twice on each rat with a 5-min interval. A cut-off time of 20 sec was set to avoid damage to the hind paw.

Evaluation of mechanical allodynia

Mechanical allodynia was evaluated by the paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) as described previously (17). The PWT was assessed using an electronic von Frey filament (Von Frey anesthesiometer; IITC Life Science, Woodland Hills, CA, USA) following PWL detection, on the same day. Rats were placed on a wire mesh platform covered with a transparent plastic dome for 30 min to acclimate to the environment. A single rigid filament (nociceptive stimulus) connected to a transducer was applied perpendicularly to the medial surface of the hind paw with increasing force. The endpoint was confirmed as paw withdrawal accompanied by head turning, biting and/or licking. The required pressure was indicated in grams and was considered to be the value of PWT. Each rat was tested three times and the averages were considered to be the final results.

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA from the L4-5 segments of the spinal cord was extracted on the 3rd day following intrathecal injection of the lentivirus. The RNA was treated with DNase I for 30 min at 37°C prior to RT-qPCR. RT-qPCR was performed using PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit (cat. no. RR037A, Takara Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan) and SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II (cat. no. RR820L; Takara Bio, Inc.). PCR was performed using the following thermocycling conditions: initial 30 sec denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec; followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 20 sec. The RT-qPCR primers of TLR4 were as follows: 5′-TCTCCAGGAAGGCTTCCAC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGCGATACAATTCGACCTGC-3′ (reverse). The RT-qPCR primers of GAPDH were as follows: 5′-GCAAGTTCAACGGCACAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCCAGTAGACTCCACGACAT-3′ (reverse). The Real-time PCR Detection System (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) continually monitored the increase in fluorescence, which was directly proportional to the PCR product. The relative expression level of TLR4 was normalized to GAPDH. The data were analyzed with the 2−∆∆Cq formula (18).

Western blot assay

The proteins from the L4-5 segments of the spinal cord were prepared on the 3rd day following injection as previously described (19,20). Protein concentrations were determined using a Bicinchoninic Acid Assay Protein Assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Proteins (30 µg) were separated by 8% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The nitrocellulose membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk for 2 h at room temperature followed with a primary antibody against TLR4 (1:500; cat. no. ab13556; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) at 4°C overnight, and then with secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse IgG; 1:1,000; cat. no. ab6789; Abcam) conjugated with horseradish peroxidase for 2 h at room temperature. The proteins were detected using Pierce ECL Plus Western Blotting Substrate (cat. no. 32134; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich-Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany; 1:500) was used as a loading control. Densitometry analysis was performed using ImageJ software (version 1.8.0; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

ELISA

The samples from the spinal tissue (L4-5) were prepared on the day following evaluating mechanical allodynia. Total protein concentrations were determined by Bradford assay and the results were then adjusted for sample size. ELISAs for tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (cat. no. 900-K73) and interleukin (IL)-1β (cat. no. 900-K91) were carried out following the manufacturer's protocol (Peprotech EC Ltd., London, UK) (11). The results were obtained by analyzing the standard curves.

Statistical analysis

The behavioral and ELISA data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of 6 rats per group. Tests were performed on six groups (sham, CCI, CCI + Lv-mismatch, CCI + LvOn-siTLR4 + NS, CCI + Dox and CCI + LvOn-siTLR4 + Dox) one day prior to and 1, 3, 5 and 7 days following intrathecal administration of the lentivirus. All assays were performed in triplicate. Intergroup differences were statistically analyzed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's post hoc test for multiple comparisons. The RT-qPCR data are presented as the mean ± SEM and represent the normalized averages that were derived from six samples for each group. The protein results are presented as fold-changes compared with the sham group. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM and represent the normalized averages that were derived from six samples for each group. Intergroup differences, in the RT-qPCR and protein expression data, were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc analysis. All data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism software (version 5; GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Construction of lentivirus

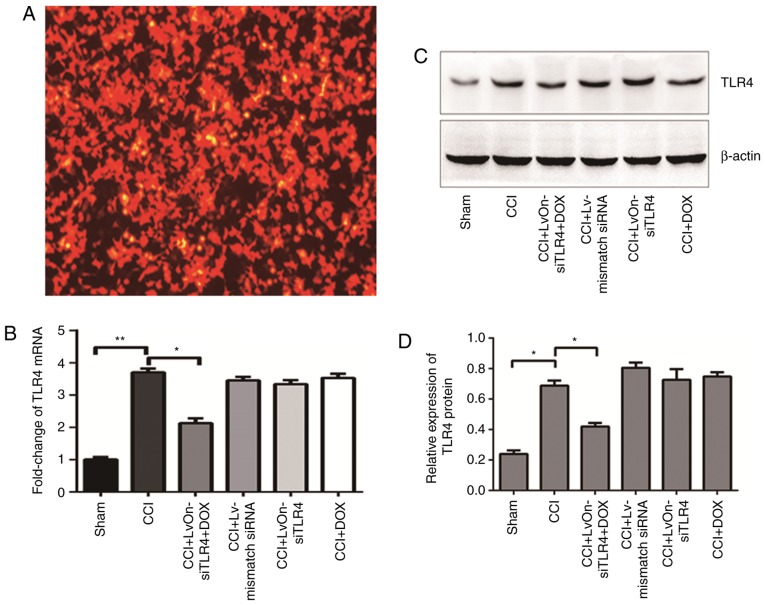

The location of the lentivirus could be tracked by RFP expression due to the lentiviral vector system. As presented in Fig. 1A, red fluorescence was observed in the 293T cells, which suggested that the constructed recombinant lentivirus LvOn-siTLR4 was successfully constructed and transfected into 293T cells; and red fluorescence was also used as a tracer for the subsequent experiments.

Figure 1.

LvOn-siTLR4 infected 293T cells and the relative alterations in the target molecule. (A) Red fluorescence indicated successful lentiviral infection of 293T cells (magnification, ×100). (B) mRNA expression of TLR4. Nerve ligation increased the mRNA expression of TLR4 in the CCI group when compared with the Sham group. **P<0.01; n=6. Following delivery of LvOn-siTLR4 with Dox, the TLR4 mRNA expression induced by CCI surgery decreased significantly when compared with the CCI group. *P<0.05; n=6. (C) Western blotting assay and (D) TLR4 protein expression densitometry results. The western blot assay revealed that the expression of TLR4 increased in the CCI group when compared with the sham group. *P<0.05; n=6. The protein expression of TLR4 was downregulated in the LvOn-siTLR4 with Dox group when compared with the CCI group. *P<0.05, one-way analysis of variance; n=6. TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4; si, small interfering RNA; CCI, chronic constriction injury; Dox, doxycycline; Lv, lentivirus.

LvOn-siTLR4 with Dox decreases TLR4 expression in CCI rats

The mRNA and protein expression of TLR4 were detected on the 3rd day following injection. As presented in Fig. 1B, the expression of TLR4 mRNA increased significantly in the rats that received the CCI procedure when compared with the sham group (P<0.01, n=6). Compared with the Lv-mismatch siRNA group, TLR4 mRNA expression decreased in the LvOn-siTLR4 with Dox group (P<0.05, n=6), suggesting that the siRNA used in the present study was effective. In contrast to the LvOn-siTLR4 and Dox groups, the TLR4 mRNA expression decreased in the LvOn-siTLR4 with Dox group (P<0.05, n=6), which indicated that the downregulation was Dox-induced, but Dox alone was not effective. The western blot assay (Fig. 1C) demonstrated similar results as the protein expression of TLR4 increased in the rats that underwent the CCI procedure compared with the rats of the sham group. The protein expression of TLR4 was downregulated in the LvOn-siTLR4 with Dox group when compared with the other four groups that received CCI surgery (P<0.05, n=6), which suggested that the siRNA expressed by the lentivirus interfered with the expression of TLR4 and was induced by oral Dox administration (Fig. 1D).

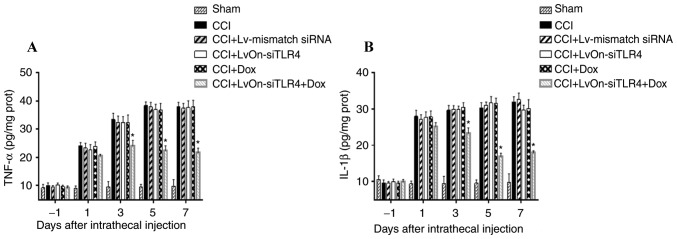

TNF-a and IL-1β expression

TNF-α and IL-1β expression increased in the dorsal spinal cord of CCI rats as presented in Fig. 2. No significant differences in TNF-α and IL-1β expression were detected in the CCI, Dox, LvOn-siTLR4 and Lv-mismatch siRNA groups (P>0.05). When compared with these four groups, TNF-α and IL-1β were significantly lower in the LvOn-siTLR4 with Dox group (P<0.05, n=6), indicating that TNF-α and IL-1β were downregulated as TLR4 was decreased by siRNA application.

Figure 2.

Expression of TNF-α and IL-1β. (A) Expression of TNF-α. TNF-α increased in the spinal cord of the CCI group. No significant difference in TNF-α expression was detected in the CCI, Dox, LvOn-siTLR4 and Lv-mismatch siRNA groups (P>0.05). TNF-α levels were significantly decreased on the 3rd, 5th and 7th day in the LvOn-siTLR4 with Dox group (n=6). (B) Expression of IL-1β. CCI-induced IL-1β expression in spinal cord tissues was increased. IL-1β production in the LvOn-siTLR4 with Dox group was significantly decreased on the 3rd, 5th and 7th day (n=6). *P<0.05 vs. CCI group, Dox group, LvOn-siTLR4 group and Lv-mismatch siRNA group. TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4; si, small interfering RNA; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; CCI, chronic constriction injury; ANOVA, analysis of variance; Dox, doxycycline; Lv, lentivirus.

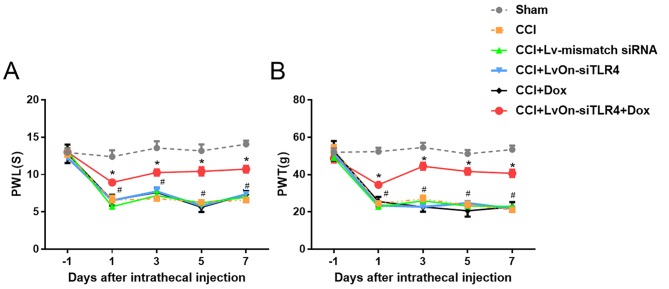

LvOn-siTLR4 with Dox attenuates NP in CCI rats

To examine the impact of LvOn-siTLR4 on the nociception of NP rats, PWT and PWL were used to measure mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia, respectively. Compared with the sham group, rats in the CCI, LvOn-siTLR4 and Lv-mismatch siRNA groups presented with a reduction in mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia (Fig. 3; P<0.05, n=6). In addition, when compared with these three groups PWT (Fig. 3A) and PWL (Fig. 3B) in the LvOn-siTLR4 with Dox group decreased on 1, 3, 5 and 7 days post-injection (P<0.05, n=6). Furthermore, there were no significant differences in the PWT and PWL between the Dox and CCI groups (P>0.05), indicating that Dox did not contribute to the alterations in pain threshold.

Figure 3.

Impact of LvOn-siTLR4 on PWL and PWT in CCI rats. On the 1st, 3rd, 5th and 7th day following intrathecal injection, CCI rats that received intrathecal LvOn-siTLR4 with oral Dox, exhibited significantly attenuated (A) thermal hyperalgesia and (B) mechanical allodynia. *P<0.05 vs. CCI group, Dox group, LvOn-siTLR4 group and Lv-mismatch siRNA group. TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4; si-, small interfering RNA; PWL, paw withdrawal latency; PWT, paw withdrawal threshold; CCI, chronic constriction injury; ANOVA, analysis of variance; Dox, Doxycycline; Lv, lentivirus.

Discussion

In the present study, a tetracycline inducible lentivirus-expressing siRNA against TLR4 in NP was investigated in CCI rats. The results revealed that intrathecal injection of the lentivirus LvOn-siTLR4 with oral administration of Dox markedly decreased the expression of TLR4 and downregulated TNF-α and IL-1β in the spinal cord. Furthermore, the thermal and mechanical pain hypersensitivity induced by CCI was effectively alleviated by LvOn-siTLR4 (with oral administration of Dox). In addition, siRNA expression was controlled by oral administration of Dox. These results suggested that the inducible lentivirus-mediated siRNA targeting TLR4 may be applied for NP in an experimental setting. With more comprehensive experiments, a novel method to treat NP using LvOn-siTLR4 may be developed.

In recent years, TLR4 has been considered to serve an increasing number of important roles in chronic pain and pruritus (21). Activated TLR4 interacts with myeloid differentiation primary-response protein 88 (22,23) and leads to the translocation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB to the nucleus, which results in the release of inflammatory factors including TNF-α and IL-1β (24,25). A number of factors in the TLR4 signaling pathway, including NF-κB and TNF-α, are involved in the development of central pain sensitization. Downregulation of TLR4 by an antagonist or siRNA, leading to a decrease in the expression of these pain-associated factors, has been reported to relieve pain hypersensitivity in different chronic pain models (11,17). The NP rat model of CCI used in the present study demonstrated similar results as decreasing the expression of TLR4 attenuated hyperalgesia and allodynia in the rats. Therefore, TLR4 presents a potential target for NP treatment.

The RNAi technique is a useful tool in gene therapy as it precisely targets therapeutics for any specific subtype (26). It utilizes double-stranded RNAs to form RNA duplexes of specific structure and length, which degrade homologous sequences of mRNA to siRNA and induce sequence-specific gene silencing (27,28). In the application of this technique, the efficiency, specificity and stability of siRNA in target cells should be taken into consideration (28,29). The TLR4 siRNA used in the present study has been observed to have specificity and efficiency in downregulating TLR4 and alleviating NP in CCI rats (9). The lentivirus LvOn-siTLR4 employed in the present study was also revealed to have the ability to express stable siRNA in rats. It was successfully transfected into the dorsal horn and persisted for 5 weeks following the intrathecal injection into rats in a bone cancer pain model in the authors' previous study (11). In this case, the lentivirus demonstrated potential in treating NP in an efficient, specific and stable manner. In the NP model of CCI rats, hyperalgesia and allodynia were reduced in the present study following injection with the virus, which suggested that it exhibited a certain validity in applying the virus LvOn-siTLR4 for NP treatment.

In the present study, a tetracycline-regulated system (Tet-on) was introduced into the lentivirus to control the level of TLR4 expression. In this typical Tet-on system, a Tet-regulated transactivator (tTA) was addressed by inserting a tetracycline repressor into a herpes simplex virus VP 16 transactivation domain (29). With the presence of Tet or Dox, the tTA would not bind to the operator sequences and therefore, led to the activation of transcription (30,31). In contrast, the tTA would bind to the operator sequences and inhibit transcriptional activation without Dox. The level of TLR4 expression was not affected. Through this system, downregulation of TLR4 is controlled by Tet or Dox. In the present study, the decrease in TLR4 was only observed in the LvOn-siTLR4 with Dox group, while rats in the LvOn-siTLR4 group demonstrated no regulatory effect on TLR4, which indicated that the expression of TLR4 siRNA was controlled by Dox. Therefore, this provides a method of controlling the timing and levels of TLR4 through oral Dox application in order to maintain the protein concentrations within a therapeutic window for clinical usage (11).

In conclusion, the TLR4 siRNA expressed by the lentivirus effectively and stably reduced TLR4 expression in the spinal cord of CCI rats. The Tet-on system was utilized to induce the expression TLR4 in the present study. The inducible lentivirus LvOn-siTLR4 reduced the thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia of CCI rats by inhibiting TLR4 in the spinal cord, which may present a novel strategy for NP treatment in the future. However, the dose-dependent manner of Dox in regulating TLR4 was not investigated in the present study and therefore, further studies are required.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81671082) to Feixiang Wu and the Xinchen Foster Fund for Anesthesiologists in Shanghai to Feixiang Wu.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during the present study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

YS, FW, YL, WY and YZ conceived and designed the study. YL, YZ, RP, MC, XW and EK performed the experiments and analyzed the data. YL and YZ wrote the manuscript. WY, YS and FW reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were approved by the Administrative Committee of Experimental Animal Care and Use of Second Military Medical University (Shanghai, China), and conformed to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1978).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Katz NP, Rowbotham MC, Peirce-Sandner S, Cerny I, Clingman CS, Eloff BC, Farrar JT, Kamp C, et al. Evidence-based clinical trial design for chronic pain pharmacotherapy: A blueprint for ACTION. Pain. 2011;152(3 Suppl):S107–S115. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ivanova JI, Birnbaum HG, Yushkina Y, Sorg RA, Reed J, Merchant S. The prevalence and economic impact of prescription opioid-related side effects among patients with chronic noncancer pain. J Opioid Manag. 2013;9:239–254. doi: 10.5055/jom.2013.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jurga AM, Rojewska E, Piotrowska A, Makuch W, Pilat D, Przewlocka B, Mika J. Blockade of Toll-like receptors (TLR2, TLR4) attenuates pain and potentiates buprenorphine analgesia in a rat neuropathic pain model. Neural Plast. 2016;2016:5238730. doi: 10.1155/2016/5238730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma YQ, Chen YR, Leng YF, Wu ZW. Tanshinone IIA downregulates HMGB1 and TLR4 expression in a spinal nerve ligation model of neuropathic pain. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:639563. doi: 10.1155/2014/639563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutchinson MR, Zhang Y, Brown K, Coats BD, Shridhar M, Sholar PW, Patel SJ, Crysdale NY, Harrison JA, Maier SF, et al. Non-stereoselective reversal of neuropathic pain by naloxone and naltrexone: Involvement of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:20–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bettoni I, Comelli F, Rossini C, Granucci F, Giagnoni G, Peri F, Costa B. Glial TLR4 receptor as new target to treat neuropathic pain: Efficacy of a new receptor antagonist in a model of peripheral nerve injury in mice. Glia. 2008;56:1312–1319. doi: 10.1002/glia.20699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaur IP, Sharma G. siRNA: A new approach to target neuropathic pain. BioDrugs. 2012;26:401–412. doi: 10.1007/BF03261897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu F, Liu Y, Lv X, Miao X, Sun Y, Yu W. Small interference RNA targeting TLR4 gene effectively attenuates pulmonary inflammation in a rat model. BioMed Res Int. 2012;2012:406435. doi: 10.1155/2012/406435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu FX, Bian JJ, Miao XR, Huang SD, Xu XW, Gong DJ, Sun YM, Lu ZJ, Yu WF. Intrathecal siRNA against Toll-like receptor 4 reduces nociception in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Int J Med Sci. 2010;7:251–259. doi: 10.7150/ijms.7.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu F, Pan R, Chen J, Sugita M, Chen C, Tao Y, Yu W, Sun Y. Lentivirus mediated siRNA against GluN2B Subunit of NMDA receptor reduces nociception in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:871637. doi: 10.1155/2014/871637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan R, Di H, Zhang J, Huang Z, Sun Y, Yu W, Wu F. Inducible lentivirus-mediated siRNA against TLR4 reduces nociception in a rat model of bone cancer pain. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:523896. doi: 10.1155/2015/523896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett GJ, Xie YK. A peripheral mononeuropathy in rat that produces disorders of pain sensation like those seen in man. Pain. 1988;33:87–107. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ge Y, Wu F, Sun X, Xiang Z, Yang L, Huang S, Lu Z, Sun Y, Yu WF. Intrathecal infusion of hydrogen-rich normal saline attenuates neuropathic pain via inhibition of activation of spinal astrocytes and microglia in rats. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Milligan ED, Hinde JL, Mehmert KK, Maier SF, Watkins LR. A method for increasing the viability of the external portion of lumbar catheters placed in the spinal subarachnoid space of rats. J Neurosci Methods. 1999;90:81–86. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0270(99)00075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain. 1988;32:77–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu F, Miao X, Chen J, Sun Y, Liu Z, Tao Y, Yu W. Down-regulation of GAP-43 by inhibition of caspases-3 in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2012;5:948–955. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lan LS, Ping YJ, Na WL, Miao J, Cheng QQ, Ni MZ, Lei L, Fang LC, Guang RC, Jin Z, Wei L. Down-regulation of Toll-like receptor 4 gene expression by short interfering RNA attenuates bone cancer pain in a rat model. Mol Pain. 2010;6:2. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 (-Delta Delta C (T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.An G, Lin TN, Liu JS, Xue JJ, He YY, Hsu CY. Expression of c-fos and c-jun family genes after focal cerebral ischemia. Ann Neurol. 1993;33:457–464. doi: 10.1002/ana.410330508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu F, Miao X, Chen J, Liu Z, Tao Y, Yu W, Sun Y. Inhibition of GAP-43 by propentofylline in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:1516–1522. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu T, Han Q, Chen G, Huang Y, Zhao LX, Berta T, Gao YJ, bJi RR. Toll-like receptor 4 contributes to chronic itch, alloknesis, and spinal astrocyte activation in male mice. Pain. 2016;157:806–817. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vijayan V, Khandelwal M, Manglani K, Gupta S, Surolia A. Methionine down-regulates TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signalling in osteoclast precursors to reduce bone loss during osteoporosis. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:107–121. doi: 10.1111/bph.12434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wieland CW, Florquin S, Maris NA, Hoebe K, Beutler B, Takeda K, Akira S, van der Poll T. The MyD88-dependent, but not the MyD88-independent, pathway of TLR4 signaling is important in clearing nontypeable haemophilus influenzae from the mouse lung. J Immunol. 2005;175:6042–6049. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin J, Wang H, Li J, Wang Q, Zhang S, Feng N, Fan R, Pei J. κ-Opioid receptor stimulation modulates TLR4/NF-κB signaling in the rat heart subjected to ischemia-reperfusion. Cytokine. 2013;61:842–848. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song Y, Shi Y, Ao LH, Harken AH, Meng XZ. TLR4 mediates LPS-induced HO-1 expression in mouse liver: Role of TNF-α and IL-1β. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:1799–1803. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i8.1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ichim TE, Li M, Qian H, Popov IA, Rycerz K, Zheng X, White D, Zhong R, Min WP. RNA Interference: A potent tool for gene-specific therapeutics. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:1227–1236. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00530.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elbashir SM, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. RNA interference is mediated by 21- and 22-nucleotide RNAs. Genes Dev. 2001;15:188–200. doi: 10.1101/gad.862301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lambeth LS, Smith CA. Short hairpin RNA-mediated gene silencing. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;942:205–232. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-119-6_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Welman A, Barraclough J, Dive C. Tetracycline regulated systems in functional oncogenomics. Transl Oncogenomics. 2007;2:17–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pluta K, Luce MJ, Bao L, Agha-Mohammadi S, Reiser J. Tight control of transgene expression by lentivirus vectors containing second-generation tetracycline-responsive promoters. J Gene Med. 2005;7:803–817. doi: 10.1002/jgm.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moriyama H, Moriyama M, Sawaragi K, Okura H, Ichinose A, Matsuyama A, Hayakawa T. Tightly regulated and homogeneous transgene expression in human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells by lentivirus with tet-off system. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during the present study are included in this published article.