Abstract

Previous studies have identified recurrent oncogenic mutations in colorectal cancer (CRC), but there is limited CRC genomic data from the Chinese Han population. Whole-genome sequencing was performed on 10 primary CRC tumors and matched adjacent normal tissues from patients from the Han population in Shanghai, at an average of 27.8× and 27.9× coverage, respectively. In the 10 tumor samples, 32 significant somatic mutated genes were identified, 13 of which were also reported as CRC mutations in The Cancer Genome Atlas Network. All the mutated genes were enriched in functions associated with channel activity, which has rarely been reported in previous studies investigating CRC. Furthermore, 21 chromosomal rearrangements were detected and 4 rearrangements encoded predicted in-frame fusion proteins, including a fusion of phosphorylase kinase regulatory subunit b and NOTCH2 demonstrated in 2 out of 10 tumors. Chromosome 8 was amplified in 1 tumor and chromosome 20 was amplified in 2 out of 10 CRC patients. The present study produced a genomic mutation profile of CRC, which provides a valuable resource for further insight into the mutations that characterize CRC in patients from the Han population in Shanghai, eastern China.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, whole-genome sequencing, chromosomal rearrangement, copy number variation

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common malignancy and one of the leading causes of cancer-associated mortality worldwide (1). For tumor molecular profiling of CRC, several organizations have completed large-scale sequencing projects, including The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (2), Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) (3), Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (4) and Genentech, Inc. (5). Exome-wide sequencing has identified recurrent gene mutations and dysregulated signaling pathways that may contribute to carcinogenesis, including APC, WNT signaling pathway regulator (APC), tumor protein p53 (TP53), KRAS proto-oncogene, GTPase (KRAS) and titin (TTN) genes, and the WNT, tumor growth factor-β, phosphoinositide 3-kinase and P53 signaling pathways (2). TCGA has detailed subgroups of tumors characterized by hypermutation (16%), or by a high degree of microsatellite instability (MSI-H) and non-hypermutated (84%). Together with clinical annotations, these molecular profiling methods can be used to identify potentially actionable tumor biomarkers that may be useful for clinical practice.

Over the past decades, the 5-year relative survival rate of patients with CRC has increased markedly (6). In China, ~376,000 people are diagnosed with CRC per year, which is 2.5 times higher than in the United States (7,8). Additionally, 5-year relative survival is substantially lower in China (~47.2%) compared with in the United States (~66%) (9). In China, survival of patients with CRC in urban areas, including Shanghai, is markedly higher than in rural areas, due to differences in socioeconomics and healthcare standards (9). Next-generation sequencing enables precision medicine, the tailoring of treatments based on unique genomic variations of each patient's tumor. Sequencing a panel of CRC-associated genes may identify actionable genomic driver mutations and further determine mutational burden in CRC, which is more cost effective, efficient and achieves higher sequencing depth than whole-exome sequencing. CRC panel design is mainly based on the TCGA database. Sequencing data generated from TCGA (2) or previous studies (3–5) are essential sources, but tumors from Asian populations have not been the subject of comprehensive evaluation. Furthermore, in the previous studies (10–13) almost all exome-wide sequencing in CRC, including whole-exome sequencing and target sequencing, were limited to the detection of single nucleotide variations (SNVs) and small insertion and deletions (InDels) in genes. While structure variations, including copy number variation (CNV) and chromosomal rearrangement, are also key factors in the process of cancer development.

In the present study, 10 CRC patients were recruited at the Shanghai Tenth People's Hospital (Shanghai, China) as a representative sample of CRC patients in the Shanghai Han population and Chinese urban population. The whole genomes of the 10 CRC patient tumors and matched normal tissues were sequenced. A comprehensive analysis was performed, including identification of SNVs, InDels, CNVs and chromosomal rearrangement, which not only validated results from TCGA to a certain extent, but also resulted in novel findings.

Patients and methods

Patients and samples

Fresh primary colorectal tumor tissues and matched adjacent normal tissues were collected from 10 patients with pathologically confirmed CRC at the Shanghai Tenth People's Hospital Affiliated to Tongji University between March and May 2015. Patient clinical characteristics are presented in Table I. Patients were numbered CRC-1 to 10. The median age was 62 years (range, 43–82 years), 6 cases were female, 8 cases exhibited colon cancer and 2 were rectal cancer. No patients had received therapeutic procedures, including chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Samples were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C prior to analysis.

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of ten colorectal cancer patients.

| Patients | Sex | Age | Clinical diagnosis | MSI | TNM stage | Differentiation | Location | Size (cm) | Lymphatic metastasis | Distant metastasis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRC-1 | Female | 62 | Colon cancer | MSS | T3N0M0 | Moderately | Sigmoid colon | 6×4×1 | 0/12 | No |

| CRC-2 | Female | 68 | Colon cancer | MSS | T3N1M0 | Moderately | Right colon | 7×4.5×4 | 1/9 | No |

| CRC-3 | Female | 58 | Rectal cancer | MSS | T4N1M0 | Moderately | Rectum | 4.5×3×3 | 1/5 | No |

| CRC-4 | Male | 80 | Colon cancer | MSS | T3N1M0 | Poorly-moderately | Ascending colon | 4×3×1.5 | 3/13 | No |

| CRC-5 | Male | 57 | Colon cancer | MSS | T1N0M0 | Moderately-well | Colon | 1×1.5×1 | 0/5 | No |

| CRC-6 | Female | 75 | Colon cancer | MSS | T4aN1M1 | Moderately | Ascending colon | 9.5×7×2.5 | 1/14 | Yes |

| CRC-7 | Male | 82 | Rectal cancer | MSI-L | T4bN0M0 | Moderately | Rectum | 6×5.5×1.5 | 0/15 | No |

| CRC-8 | Male | 62 | Colon cancer | MSS | T3N0M0 | Moderately | Transverse colon | 4×3.5×2 | 0/12 | No |

| CRC-9 | Female | 60 | Colon cancer | MSI-H | T4bN0M0 | Poorly-moderately | Transverse colon | 6×4.5×4 | 0/17 | No |

| CRC-10 | Female | 43 | Colon cancer | MSS | T1N1M0 | Moderately-well | Colon | 5.5×5×4 | 1/15 | No |

MSI, microsatellite instability; MSS, microsatellite stability; MSI-L, microsatellite instability-low; MSI-H, microsatellite instability-high.

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from fresh frozen tissue using QIAamp DNA Minikit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturers' protocol. DNA was quantified using the Qubit Fluorometer (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

Library preparation

A total of 0.5 µg DNA per sample was used as input material for the DNA library preparations. A sequencing library was generated using Truseq Nano DNA HT Sample Prep kit (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's recommendations and index codes were added to each sample. Briefly, genomic DNA samples were fragmented by sonication to a size of ~350 bp (duty factor 10%, peak incident power 175, cycles per burst 200, treatment time 180 seconds, bath temperature 4–8°C). Then, DNA fragments were end polished, A-tailed and ligated with the full-length adapter for Illumina sequencing, followed by further polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification using KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (Kapa Biosystems, Inc., Wilmington, MA, USA). Primers are based on the P5 and P7 Illumina flow cell sequences, and are suitable for the amplification of libraries prepared with full-length adapters (P5: 5′-AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATC-3′, P7: 5′-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGA-3′). Thermocycling conditions: Initial denaturation 98°C for 45 sec, denaturation 98°C for 15 sec, annealing 60°C for 30 sec, extension 72°C for 30 sec, library amplification with 3 cycles and final extension 72°C for 1 min, hold at 4°C. Subsequently, PCR products were purified by the AMPure XP system (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA, USA), libraries were analyzed for size distribution by Agilent2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) and quantified by quantitative PCR (3 nM) using KAPA Library Quantification kits (Kapa Biosystems, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The primers were the same as for the amplification procedure (P5: 5′-AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATC-3′, P7: 5′-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGA-3′). qPCR protocol for library quantification consists of an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec and combined annealing/extension at 60°C for 45 sec. A total of 6 pre-diluted DNA Standards and appropriately diluted NGS libraries are amplified at the same time. The average Cq value for each DNA standard was plotted against its known concentration to generate a standard curve. The standard curve is used to convert the average Cq values for diluted libraries to concentration, from which the working concentration of each library is calculated.

Clustering and sequencing

The clustering of the index-coded samples was performed on a cBot Cluster Generation System using HiseqX PE Cluster kit V2.5 (Illumina, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Following cluster generation, the DNA libraries were sequenced using the IlluminaHiseq platform and 150 bp paired-end reads were generated.

Bioinformatics analysis

For whole-genome sequencing, clean data was obtained following filtering adapter, low quality reads and reads with proportion of N>10%. Reads were aligned to the reference human genome (UCSC hg19; http://genome.ucsc.edu/) (14) using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner v. 0.7.12 (15). Next, the Picard and Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK v.3.2) (16) method was adopted for duplicate removal, local realignment and Base Quality Score Recalibration, and generated quality statistics, including mapped reads, mean mapping quality and mean coverage. Finally, the GATK HaplotypeCaller was used for SNV and InDel identification.

Variants were annotated using the ANNOVAR software tool (17). Annotations for mutation function (including frameshift insertion/deletion, non-frameshift insertion/deletion, synonymous SNV, nonsynonymous SNV and stopgain stoploss), mutation location [including exonic, intronic, splicing, upstream, downstream, 3′untranslated region (UTR) and 5′UTR], amino acid changes, 1000 Genomes Project data and dbSNP reference number were performed.

Somatic SNVs and InDels of tumors compared with matched normal tissue were named and functionally annotated using MuTect v. 1.1.4 (16) and Varscan2 v. 2.3.9 (18) software. Somatic mutations in coding regions were filtered (Frame_Shift_Del, Frame_Shift_Ins, In_Frame_Del, In_Frame_Ins, Missense_Mutation, Nonsense_Mutation and Nonstop_Mutation) along with challenging regions (3′Flank, 3′UTR, 5′Flank, 5′UTR, intergenic region, Splice_Site, Translation_Start_Site, RNA, Splice_Site, Translation_Start_Site). The mutations with variant allele frequency >5% were defined as high confidence mutations. MutSigCV v.0.9 (19) was used to identify significantly mutated genes (q≤0.1). Then, gene mutation data were downloaded from TCGA database (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/docs/publications/coadread_2012/) (2) and comparative analysis was performed using the sequencing data produced in the present study.

Control-FREEC v.8.7 (20) software was used for identifying and annotating CNVs, including gain, loss or copy neutral loss of heterozygosity. Structural variations, including inversion, intra-chromosomal translocation and inter-chromosomal translocation, were identified using Factera (21) software.

The mutation landscape across a cohort, including SNVs, InDels and mutational burden, were created by Genomic Visualizations in R (GenVisR) (22). The custom mutation lists of proteins were visualized by MutationMapper tool from cBioPortal (http://www.cbioportal.org/mutation_mapper.jsp) and structural variants, and copy number data were visualized using CIRCOS version 0.69 (http://www.circos.ca/) (23). Gene ontology (GO: http://www.geneontology.org/) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG: http://www.kegg.jp/) enrichment analysis was performed to investigate the biological importance of the somatic mutated genes using the ClusterProfiler in R software (10.18129/B9.bioc.clusterProfiler).

Results

Clinical and sequencing data

The 10 CRC samples were analyzed (Table I). The microsatellite instability status of the CRC-9 tumor was high (MSI-H), the CRC-7 tumor was low (MSI-L) and others were microsatellite stable.

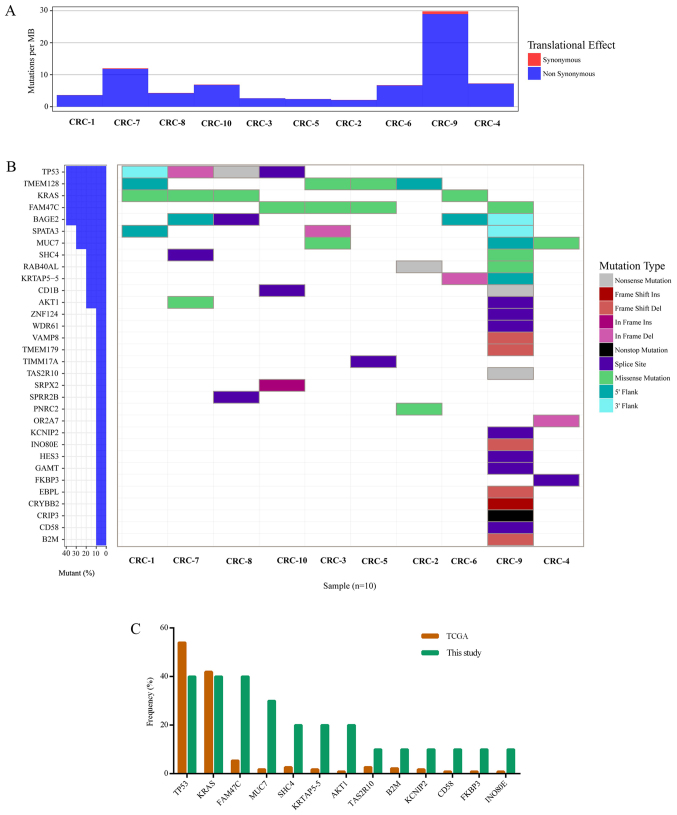

Whole-genome sequencing achieved an average of 27.8× coverage of the tumor genomes and 27.9× coverage of the germline genome (Table II). Somatic DNA alterations were analyzed, including SNVs, InDels, CNVs and chromosomal rearrangements. An overall mutation rate of ~7.78 per Mb with a range of 2.11–29.79 mutations per Mb was calculated (Table II; Fig. 1A). In study of TCGA (2), cases with mutation rates >12 per Mb were designated as hypermutated. The mutation rate of CRC-9 was 29.79 per Mb in the present study, which was the only hypermutated case (Fig. 1A).

Table II.

Summary of whole-genome sequencing results from each patients' tissues.

| Patients | Tumor coverage | Normal coverage | Mutations | Mutations per Mb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRC-1 | 29.9 | 29.4 | 1092 | 3.64 |

| CRC-2 | 27.9 | 29.0 | 634 | 2.11 |

| CRC-3 | 26.9 | 28.2 | 790 | 2.63 |

| CRC-4 | 25.7 | 27.0 | 2180 | 7.27 |

| CRC-5 | 26.6 | 28.8 | 716 | 2.39 |

| CRC-6 | 26.7 | 27.2 | 2021 | 6.74 |

| CRC-7 | 29.0 | 25.7 | 3597 | 11.99 |

| CRC-8 | 29.9 | 29.1 | 1288 | 4.29 |

| CRC-9 | 27.8 | 27.6 | 8937 | 29.79 |

| CRC-10 | 28.1 | 26.6 | 2071 | 6.90 |

| Average | 27.8 | 27.9 | 2332 | 7.78 |

Figure 1.

Significantly mutated genes in colorectal cancer. (A) The bars represent somatic mutation rate for 10 samples distinguished by color. (B) Significantly mutated genes, identified by MutSigCV (q≤0.1), are ranked mutation frequency in samples. Mutation color indicated the mutation type. (C) Comparison of mutation frequency between TCGA and the sequencing data. CRC, colorectal cancer; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas.

Significantly mutated somatic genes

The MutSigCV tool was used to define significantly mutated genes and identified 32 significantly mutated genes (Fig. 1B). Fig. 1 presents the significantly mutated genes (Fig. 1B), mutation type (Fig. 1B), frequency and tumor mutation burden (Fig. 1A). The five most frequently mutated genes were TP53 (4/10), transmembrane protein 128 (TMEM128; 4/10), KRAS (4/10), FAM47C (4/10) and BAGE family member 2 (BAGE2; 4/10).

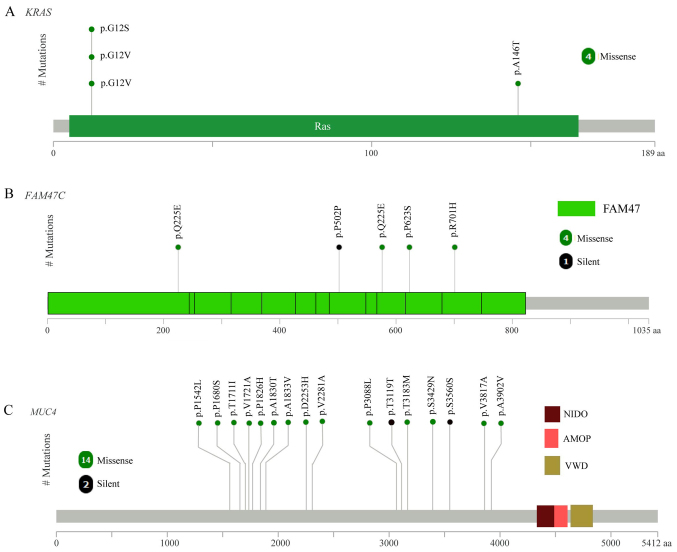

The mutation frequency of the 32 significantly mutated genes was compared with TCGA data (Fig. 1C). Of these 32 genes, 13 were detected by TCGA, including TP53, KRAS, FAM47C, MUC7, SHC adaptor protein 4, keratin associated protein 5–5 (KRTAP5-5), AKT serine/threonine kinase 1, taste 2 receptor member 10 (TAS2R10), β-2-microglobulin (B2M), potassium voltage-gated channel interacting protein 2 (KCNIP2), cluster of differentiation (CD)58, FK506 binding protein 3 (FKBP3) and INO80 complex subunit E (INO80E; Fig. 1C). Among these 13 genes, the top three genes with the highest mutation frequency in the present study and TCGA data were TP53, KRAS and FAM47C (4/10). As expected, the mutated KRAS gene had oncogenic codon 12 mutations (3/10 samples; Fig. 2A) and another mutation was in codon 146 of KRAS (1/10 samples; Fig. 2A), which was in accordance with a previous study of CRC in the Chinese population (24). FAM47C was mutated in 4 out of 10 tumor samples including 4 missense mutations (p.Q225E, p.P502P, p.Q225E and p.R701H), 1 silent mutation (p.P502P) and 1 mutation in the 3′flank region, as presented in Fig. 2B. The mutation frequency of FAM47C in the COSMIC and TCGA databases was 5.71 and 5.41%, respectively (2). FAM47C encodes a product belonging to a family of proteins with unknown function. Additionally, FAM47C was mutated exclusively in KRAS wild-type tumors. Specific ones out of the 13 genes were mutated only in the tumor from patient CRC-9, including TAS2R10, B2M, KCNIP2, CD58 and INO80E. B2M had two mutations (a frame shift deletion and an insertion in 3′flank region) in the CRC-9 tumor. Previous studies reported B2M mutations in CRC and melanoma resulting in loss of expression of HLA class 1 complexes (25), suggesting these mutations benefit tumor growth by reducing antigen presentation to the immune system (26). CD58 is reported to be a surface marker that promotes self-renewal of tumor-initiating cells in CRC (27).

Figure 2.

The proportion of mutations in (A) MUC4, (B) KRAS, (C) FAM47C genes in colorectal cancer. MUC4, KRAS and FAM47C are presented in the context of protein domain models. MUC4, mucin 4; KRAS, KRAS proto-oncogene; FAM47C, family with sequence similarity 47 member C. NIDO domain, extracellular domain of unknown function in nidogen (entactin) and hypothetical proteins; AMOP domain, adhesion-associated domain present in MUC4 and other proteins; VWD domain, von Willebrand factor (vWF) type D domain.

Of the 32 significantly mutated genes, 19 were not listed in TCGA data, including BAGE2, TMEM128, spermatogenesis associated 3 (SPATA3), CD1B, RAB40A like, cysteine rich protein 3 (CRIP3), crystallin β B2, EBP like, guanidinoacetate N-methyltransferase, hes family bHLH transcription factor 3, olfactory receptor family 2 subfamily A member 7, proline rich nuclear receptor coactivator 2, small proline rich protein 2B (SPRR2B), sushi repeat containing protein X-linked 2 (SRPX2), translocase of inner mitochondrial membrane 17A (TIMM17A), TMEM179, vesicle associated membrane protein 8 (VAMP8), WD repeat domain 61 (WDR61) and zinc finger protein 124 (ZNF124). Notably, CRIP3 demonstrated a nonstop_mutation (p.*205Rext*51) and CD1B had a nonsense_mutation (p.Q221*) in the CRC-9 tumor, which was the hypermutated case (29.79 mutations per Mb).

Considering all somatic mutations in coding regions, the top 11 most frequently mutated genes were mucin 4 (MUC4; 8/10), immunoglobulin-like and fibronectin type III domain containing 1 (IGFN1; 5/10), ALMS1, centrosome and basal body associated protein (4/10), APC (4/10), family with sequence similarity 47 member C (FAM47C; 4/10), KRAS (4/10), mucin like 3 (DPCR1; 3/10), family with sequence similarity 186 member A (FAM186A; 3/10), polycystin 1, transient receptor potential channel interacting (3/10), and TTN (3/10). The most frequent mutated gene was MUC4 (8/10), with a mutation frequency that was higher compared with that reported in a previous study (2). The mutation frequency of MUC4 has been previously reported as 9.72% (Genentech) (5), 5.33% (DFCI) (3) and 2.23% (TCGA) (2). MUC4 is a major constituent of mucus that has important roles in the protection of epithelial cells and has been implicated in epithelial renewal and differentiation. The mucin gene MUC4 is reported to be a transcriptional and post-transcriptional target of the oncogene KRAS in pancreatic cancer (28). However, MUC4 was not defined as a driver gene by MutSigCV in the current study, which may due to the positions of MUC4 mutations, which were not in functional regions (Fig. 2C).

Functional enrichment analysis of mutated genes

To better understand the biological function of mutated genes, GO and KEGG enrichment analysis were performed. All mutated genes were categorized into 16 functional categories by GO enrichment (adjusted P<0.05; Table III). Notably, 11 functional categories were associated with transporter/channel activity. House et al (29) reported that voltage-gated Na+ channel activity increases colon cancer transcriptional activity and invasion via persistent mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. All mutated genes were categorized into three pathways by KEGG enrichment, including ‘neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction’, ‘alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism’ and ‘nicotine addiction’ (adjusted P<0.05).

Table III.

Functional enrichment of mutated genes by GO.

| ID | Description | P adjust | Gene count |

|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0022803 | Passive transmembrane transporter activity | 0.0004191 | 209 |

| GO:0015267 | Channel activity | 0.0004191 | 208 |

| GO:0022838 | Substrate-specific channel activity | 0.0009566 | 193 |

| GO:0001227 | Transcriptional repressor activity, RNA polymerase II transcription regulatory region sequence-specific binding | 0.0013711 | 87 |

| GO:0005216 | Ion channel activity | 0.0015965 | 185 |

| GO:0000987 | Core promoter proximal region sequence-specific DNA binding | 0.0118789 | 159 |

| GO:0022836 | Gated channel activity | 0.0118789 | 144 |

| GO:0000982 | Transcription factor activity, RNA polymerase II core promoter proximal region sequence-specific binding | 0.0150299 | 146 |

| GO:0001159 | Core promoter proximal region DNA binding | 0.0150299 | 159 |

| GO:0005267 | Potassium channel activity | 0.0186798 | 60 |

| GO:0046873 | Metal ion transmembrane transporter activity | 0.0198865 | 176 |

| GO:0022843 | Voltage-gated cation channel activity | 0.0198865 | 65 |

| GO:0000978 | RNA polymerase II core promoter proximal region sequence-specific DNA binding | 0.0308052 | 148 |

| GO:0005261 | Cation channel activity | 0.0330241 | 129 |

| GO:0005244 | Voltage-gated ion channel activity | 0.0480344 | 85 |

| GO:0022832 | Voltage-gated channel activity | 0.0480344 | 85 |

Chromosomal rearrangement

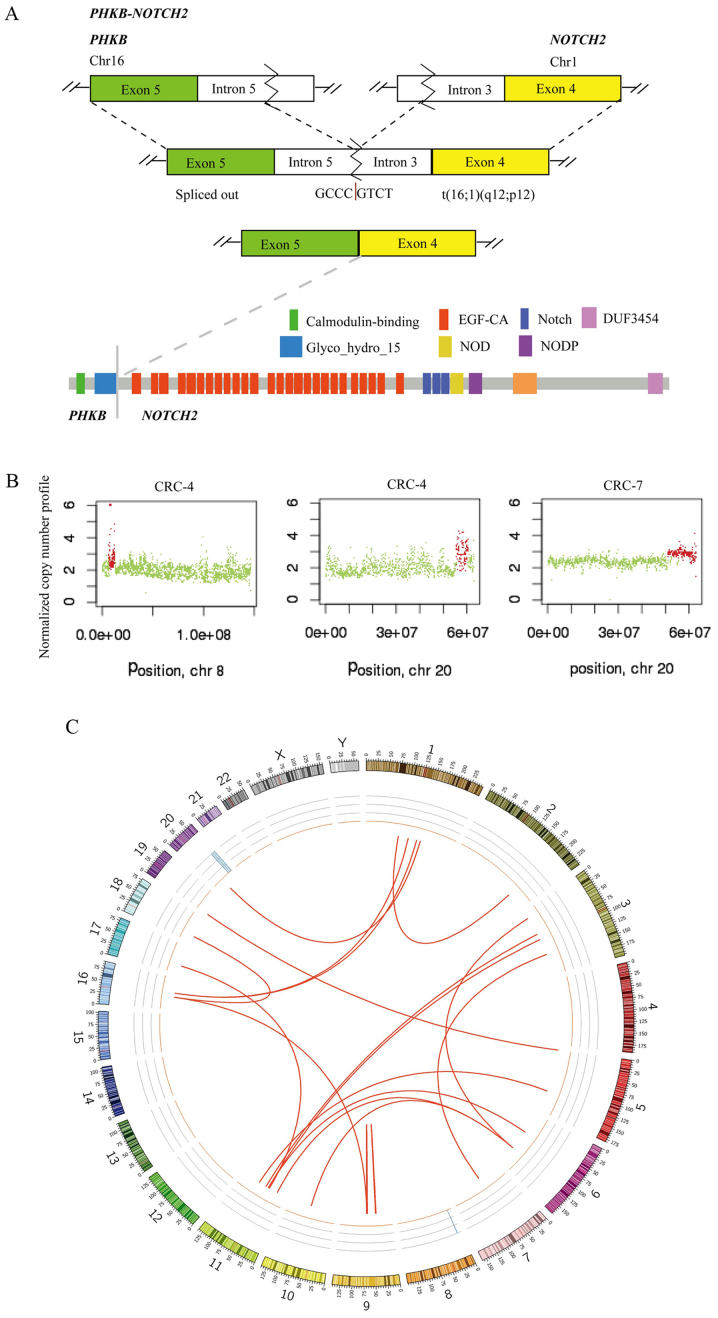

Chromosomal structural variation (SV) was also analyzed using whole-genome sequencing of 10 tumors with matched normal samples. There were 21 candidate-chromosomal rearrangements detected by filtering criterion of above 20 supporting reads, including 2 inversions and 19 translocations (Table IV). Among these, the fusion sites of 4 SVs were in gene regions, which were termed fusion genes, including, EF-hand domain family member B-mannosidase α class 1A member 1, phosphorylase kinase regulatory subunit β (PHKB)-NOTCH2 (2 samples) and polyamine modulated factor 1-FAM182B. A fusion of PHKB and NOTCH2 was identified in 2 out of 10 CRCs and the fusion occurred downstream of PHKB exon 5 and upstream of NOTCH2 exon 4 (Fig. 3A). This appears likely to enable translation of the fusion protein (the glycosyl hydrolases family 15 domain of PHKβ linked with the calcium-binding epidermal growth factor-like domain of Notch2; Fig. 3A). PHKB encodes a member of the PHKβ regulatory subunit family. PHKB was reported to promote glycogen breakdown and cancer cell survival by interacting with cell migration inducing hyaluronidase 1 (30). NOTCH2 encodes a member of the Notch family with a role in a variety of developmental processes by controlling cell fate decisions. Previous studies reported that Notch2 is a crucial regulator of self-renewal and tumorigenicity in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells (31,32) and contributes to cell growth, invasion and migration in salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma (33).

Table IV.

Predicted chromosomal rearrangement detected by Factera.

| Sample | Type | Region1 (gene, position) | Region2 (gene, position) | Fusion sites | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRC-1 | TRA | TMEM194B | Intergenic | HFM1 | Intronic | chr2:191402786 to chr1:91852783 |

| CRC-1 | TRA | ROCK1 | Intergenic | CTD-2144E22.5 | Intergenic | chr18:18519930 to chr16:35239604 |

| CRC-1 | TRA | TRIM48 | Intergenic | MTRNR2L9 | Intergenic | chr11:55021850 to chr6:61902202 |

| CRC-2 | INV | FAM27E3 | Intergenic | AL445665.1 | Intergenic | chr9:66971068 to chr9:69710933 |

| CRC-2 | TRA | UNC5B | Intergenic | MAN1A1 | Intronic | chr10:72814597 to chr6:119558701 |

| CRC-2 | TRA | ANO3 | Intergenic | MAN1A1 | Intronic | chr11:26173964 to chr6:119558701 |

| CRC-2 | TRA | AL445665.1 | Intergenic | CTD-2144E22.5 | Intergenic | chr9:69711250 to chr16:35239606 |

| CRC-2 | TRA | PPAP2C | Intergenic | PLEKHG4B | Intergenic | chr19:249186 to chr5:15867 |

| CRC-3 | TRA | EFHB | Intronic | MAN1A1 | Intronic | chr3:19950145 to chr6:119558701 |

| CRC-3 | TRA | TRIM48 | Intergenic | MTRNR2L9 | Intergenic | chr11:55021850 to chr6:61902202 |

| CRC-3 | TRA | SOX14 | Intergenic | ZNF92 | Intergenic | chr3:137265780 to chr7:64879411 |

| CRC-3 | TRA | PHKB | Intronic | NOTCH2 | Intronic | chr16:47538780 to chr1:120544074 |

| CRC-4 | INV | RP11-146D12.2 | Intergenic | CNTNAP3B | Intergenic | chr9:42416106 to chr9:44070790 |

| CRC-4 | TRA | CSNK1G3 | Intergenic | DLG2 | Intronic | chr5:122990837 to chr11:85195011 |

| CRC-4 | TRA | PHKB | Intronic | NOTCH2 | Intronic | chr16:47538780 to chr1:120544074 |

| CRC-8 | TRA | MTRNR2L1 | Intergenic | OR4C46 | Intergenic | chr17:22253139 to chr11:51568509 |

| CRC-8 | TRA | SOX14 | Intergenic | ZNF92 | Intergenic | chr3:137265780 to chr7:64879411 |

| CRC-8 | TRA | TRIM48 | Intergenic | MTRNR2L9 | Intergenic | chr11:55021850 to chr6:61902202 |

| CRC-9 | TRA | PMF1 | Intronic | FAM182B | Upstream | chr1:156186653 to chr20:26190511 |

| CRC-9 | TRA | WDR74 | Intergenic | PPP4R2 | Intergenic | chr11:62609281 to chr3:73160133 |

| CRC-9 | TRA | SOX14 | Intergenic | ZNF92 | Intergenic | chr3:137265780 to chr7:64879411 |

TRA, translocation; INV, inversion.

Figure 3.

Chromosomal structural rearrangements and copy number variations in the ten colorectal tumors. (A) A schematic of PHKB-NOTCH2 translocation is presented for the fusion transcript and predicted fusion protein. (B) Chromosome 8 was amplified in CRC-4, and chromosome 20 was amplified in CRC-4 and CRC-7. (C) Structural variations in the ten colorectal tumors displayed as CIRCOS plots. PHKB, phosphorylase kinase regulatory subunit β; CRC, colorectal cancer.

Copy number variations

Somatic CNVs in the 10 tumor tissues were analyzed using Control-FREEC software. Chromosomes 8 and 20 were amplified in CRC-4, and chromosome 20 was amplified in CRC-7 (Fig. 3B). GNAScomplex locus (GNAS) was detected in 2 out of 10 tumors (CRC-4 and CRC-7) and the GNAS copy number was 3. GNAS is located at 20q13.32. A previous study reported that amplification of the GNAS locus may contribute to the pathogenesis of breast cancer (34). In TCGA, GNAS was amplified in 8.17% tumor samples (2). In the CRC-7 tumor, a subset of genes located at chromosome 20 was amplified (copy number 3), including teashirt zinc finger homeobox 2, aurora kinase A, GNAS, SS18L1 nBAF chromatin remodeling complex subunit, regulator of telomere elongation helicase 1 and ADP ribosylation factor related protein 1. SVs of 10 tumors are presented in Fig. 3C, including chromosomal rearrangements and CNVs, displayed as CIRCOS plots.

Discussion

In the present study, whole-genome sequencing was performed on tumor and matched adjacent normal tissues from 10 patients with CRC in Shanghai. A comprehensive analysis including SNVs, InDels, CNVs and chromosomal rearrangements was performed, which identified certain recurrent and novel variations in CRC patients from the Han population in Shanghai, eastern China.

Among the significantly mutated genes, certain previously reported driver genes in CRC were identified, including TP53, KRAS, FAM47C and MUC7. Additionally, a group of driver genes were identified that have rarely been reported in CRC, including BAGE2, TMEM128, SPATA3 and CD1B. Certain well-established mutated genes, including APC and TTN, which were defined as driver genes in a previous study (2), were not significantly mutated genes in the present study. Signaling pathway analysis indicated that the mutated genes may alter pathways associated with channel activity. Notably, PHKB-NOTCH2 fusion was detected in 2 out of 10 tumors, which has not been previously reported in CRC, to the best of our knowledge. The structure of fusion proteins was also predicted. Although, further study will be required to fully understand the role of PHKB-NOTCH2 fusion.

The tumor mutation burden of the tumor of CRC-9 was 29.79 per Mb, which indicates hypermutation according to TCGA (2). TCGA identified 16% of CRCs to be hypermutated, three quarters of which are due to a mismatch repair defect phenotype, otherwise known as MSI-H. In CRC-9, 23 significantly mutated genes were identified, while the other 9 cases harbored a mean of 3.3 significantly mutated genes (range, 3–4). Somatic mutations have the potential to encode ‘non-self’ immunogenic antigens. Evidence demonstrated improved responses to programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) blockade in CRC with MSI-H (35,36). The tumor of patient CRC-9 was a locally advanced colon cancer (T4bN0M0) with poor-moderate differentiation and MSI-H. Cancer antigen (CA)12-5 and CA15-3 were at high levels following surgery, which indicated a high risk of recurrence. CRC-9 may benefit from PD-1 blockade to treat recurrence.

There are large differences in diet, living conditions and genetic background between the Han population and ethnic minorities, which are associated with CRC risk. For example, the Uyghur population in Xinjiang is predominantly Caucasian, while the Han population is mainly Mongoloid. Uyghur CRC patients have a lower age of onset, larger tumor size, more advanced stage and higher proportion of signet-ring cell carcinoma and mucinous adenocarcinoma compared with Han patients (37). A previous study reported that CRC patients in the Uyghur population exhibited a higher rate of KRAS mutation compared with the Han population (46.2% vs. 28.8%) and the mutation rate in KRAS codon 12 is higher in the Uygur population than in the Han population (38.5% vs. 17.3%) (38). In the present study, the KRAS mutation rate was 4/10 and 3/10 of mutations were in codon 12, which was at a comparable level to the Uyghur population (38).

There are limitations in this study. Firstly, the sample size was small, which lead to low statistical power to identify significantly mutated genes and could not well represent Chinese Han population. Secondly, the sequencing depth was not high enough to detect mutations with low variant allele frequency. Thirdly, further validation in samples and functional studies were not performed. Finally, due to the short time from patient enrollment, survival analysis was not performed. In future studies of a panel of CRC-associated genes, including reported recurrent genes and novel mutated genes in the present study, will be analyzed in a cohort of patients with CRC. In addition, survival analysis with genomic variations should be performed following long term follow-up for CRC patients.

In conclusion, in the present study, reported mutated genes were validated to a certain extent and novel mutations were identified, including fusion gene PHKB-NOTCH2. In addition, mutated genes were enriched in functions associated with channel activity, which has rarely been reported by previous CRC studies (2,4). The present study produced a CRC genomic mutation profile, which provides a valuable resource for further insight into CRC within the eastern Chinese Han population.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

HT and JZ wrote the manuscript; HT and HQ contributed to the study design; HT collected and interpreted the clinical data of patients; RG, NQ and XJ collected samples and performed experiments; JZ, NL and SW developed the analysis methods and provided the figures and tables. YW and MR analyzed the sequencing data. NL and HQ contributed to manuscript revision.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for the recruitment of human subjects was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Tenth People's Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine and was consistent with ethical guidelines provided by the Declaration of Helsinki (1975). Written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Patient consent for publication

All individuals whose data were used provided informed consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, Ahnen DJ, Meester RGS, Barzi A, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:177–193. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Genome Atlas Network: Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giannakis M, Mu XJ, Shukla SA, Qian ZR, Cohen O, Nishihara R, Bahl S, Cao Y, Amin-Mansour A, Yamauchi M, et al. Genomic correlates of immune-cell infiltrates in colorectal carcinoma. Cell Rep. 2016;17:1206. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brannon AR, Vakiani E, Sylvester BE, Scott SN, McDermott G, Shah RH, Kania K, Viale A, Oschwald DM, Vacic V, et al. Comparative sequencing analysis reveals high genomic concordance between matched primary and metastatic colorectal cancer lesions. Genome Biol. 2014;15:454. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0454-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seshagiri S, Stawiski EW, Durinck S, Modrusan Z, Storm EE, Conboy CB, Chaudhuri S, Guan Y, Janakiraman V, Jaiswal BS, et al. Recurrent R-spondin fusions in colon cancer. Nature. 2012;488:660–664. doi: 10.1038/nature11282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeng H, Zheng R, Guo Y, Zhang S, Zou X, Wang N, Zhang L, Tang J, Chen J, Wei K, et al. Cancer survival in China, 2003–2003: A population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:1921–1930. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cajuso T, Hanninen UA, Kondelin J, Gylfe AE, Tanskanen T, Katainen R, Pitkänen E, Ristolainen H, Kaasinen E, Taipale M, et al. Exome sequencing reveals frequent inactivating mutations in ARID1A, ARID1B, ARID2 and ARID4A in microsatellite unstable colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:611–623. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashktorab H, Daremipouran M, Devaney J, Varma S, Rahi H, Lee E, Shokrani B, Schwartz R, Nickerson ML, Brim H. Identification of novel mutations by exome sequencing in African American colorectal cancer patients. Cancer. 2015;121:34–42. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oh BY, Cho J, Hong HK, Bae JS, Park WY, Joung JG, Cho YB. Exome and transcriptome sequencing identifies loss of PDLIM2 in metastatic colorectal cancers. Cancer Manag Res. 2017;9:581–589. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S149002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagahashi M, Wakai T, Shimada Y, Ichikawa H, Kameyama H, Kobayashi T, Sakata J, Yagi R, Sato N, Kitagawa Y, et al. Genomic landscape of colorectal cancer in Japan: Clinical implications of comprehensive genomic sequencing for precision medicine. Genome Med. 2016;8:136. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0387-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, Devon K, Dewar K, Doyle M, FitzHugh W, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with burrows-wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, Garimella K, Altshuler D, Gabriel S, Daly M, DePristo MA. The genome analysis toolkit: A mapreduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: Functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koboldt DC, Zhang Q, Larson DE, Shen D, McLellan MD, Lin L, Miller CA, Mardis ER, Ding L, Wilson RK. VarScan 2: Somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res. 2012;22:568–576. doi: 10.1101/gr.129684.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Polak P, Kryukov GV, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, Carter SL, Stewart C, Mermel CH, Roberts SA, et al. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature. 2013;499:214–218. doi: 10.1038/nature12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boeva V, Popova T, Bleakley K, Chiche P, Cappo J, Schleiermacher G, Janoueix-Lerosey I, Delattre O, Barillot E. Control-FREEC: A tool for assessing copy number and allelic content using next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:423–425. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newman AM, Bratman SV, Stehr H, Lee LJ, Liu CL, Diehn M, Alizadeh AA. FACTERA: A practical method for the discovery of genomic rearrangements at breakpoint resolution. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:3390–3393. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skidmore ZL, Wagner AH, Lesurf R, Campbell KM, Kunisaki J, Griffith OL, Griffith M. GenVisR: Genomic Visualizations in R. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:3012–3014. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krzywinski M, Schein J, Birol I, Connors J, Gascoyne R, Horsman D, Jones SJ, Marra MA. Circos: An information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19:1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang J, Zheng J, Yang Y, Lu J, Gao J, Lu T, Sun J, Jiang H, Zhu Y, Zheng Y, et al. Molecular spectrum of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA mutations in chinese colorectal cancer patients: Analysis of 1,110 cases. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18678. doi: 10.1038/srep18678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernal M, Ruiz-Cabello F, Concha A, Paschen A, Garrido F. Implication of the β2-microglobulin gene in the generation of tumor escape phenotypes. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61:1359–1371. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1321-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network: Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513:202–209. doi: 10.1038/nature13480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu S, Wen Z, Jiang Q, Zhu L, Feng S, Zhao Y, Wu J, Dong Q, Mao J, Zhu Y. CD58, a novel surface marker, promotes self-renewal of tumor-initiating cells in colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2015;34:1520–1531. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vasseur R, Skrypek N, Duchêne B, Renaud F, Martínez-Maqueda D, Vincent A, Porchet N, Van Seuningen I, Jonckheere N. The mucin MUC4 is a transcriptional and post-transcriptional target of K-ras oncogene in pancreatic cancer. Implication of MAPK/AP-1, NF-κB and RalB signaling pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1849:1375–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.House CD, Wang BD, Ceniccola K, Williams R, Simaan M, Olender J, Patel V, Baptista-Hon DT, Annunziata CM, Gutkind JS, et al. Voltage-gated Na+ channel activity increases colon cancer transcriptional activity and invasion via persistent MAPK signaling. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11541. doi: 10.1038/srep11541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terashima M, Fujita Y, Togashi Y, Sakai K, De Velasco MA, Tomida S, Nishio K. KIAA1199 interacts with glycogen phosphorylase kinase beta-subunit (PHKB) to promote glycogen breakdown and cancer cell survival. Oncotarget. 2014;5:7040–7050. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayashi Y, Osanai M, Lee GH. NOTCH2 signaling confers immature morphology and aggressiveness in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2015;34:1650–1658. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu WR, Zhang R, Shi XD, Yi C, Xu LB, Liu C. Notch2 is a crucial regulator of self-renewal and tumorigenicity in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2016;36:181–188. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.4831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qu J, Song M, Xie J, Huang XY, Hu XM, Gan RH, Zhao Y, Lin LS, Chen J, Lin X, et al. Notch2 signaling contributes to cell growth, invasion, and migration in salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma. Mol Cell Biochem. 2016;411:135–141. doi: 10.1007/s11010-015-2575-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia-Murillas I, Sharpe R, Pearson A, Campbell J, Natrajan R, Ashworth A, Turner NC. An siRNA screen identifies the GNAS locus as a driver in 20q amplified breast cancer. Oncogene. 2014;33:2478–2486. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Kemberling H, Eyring AD, Skora AD, Luber BS, Azad NS, Laheru D, et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509–2520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Aulakh LK, Lu S, Kemberling H, Wilt C, Luber BS, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017;357:409–413. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roukeyan K, Yue N, Liang LP, Zhao F. Clinicopathological features and expression of hMLH1 and hMSH2 in Uygur and Han patients with colorectal carcinoma. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2015;23:2382–2388. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eli M, Mollayup A, Muattar, Liu C, Zheng C, Bao YX. K-ras genetic mutation and influencing factor analysis for Han and Uygur nationality colorectal cancer patients. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:10168–10177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.