Abstract

Ba#ckground/Obje#ctive: To examine the psychometric properties of the Conners 3 ADHD Index (Conners 3 AI) and the Conners Early Children Global Index (Conners ECGI) parents’ form (PF) and teachers’ form (TF) in Spanish schoolers. Method: Two-phase cross-sectional study. In the first phase, information was gathered from teachers (n = 1,796) and parents (n = 882) of 4-5 and 10-11 year-old children. In the second phase (n = 196), children at risk of ADHD and controls were individually assessed. Results: The results confirmed the two-factor structure of the Conners 3 ADHD Index, which contains hyperactive-impulsive and inattentive symptoms, and the two-factor structure of the Conners ECGI PF, consisting of emotional lability and restless-impulsive symptoms. In contrast with the original version, the Conners ECGI TF presented an additional inattentive factor. Moderate-to-high rates of evidence of convergent validity with Child Behavior Checklist and Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders & Schizophrenia, and evidence of external validity (academic achievement) were found. Scores were significantly higher in boys than in girls, for both indexes. Raw scores corresponding to clinical T-scores were higher than the original version. Conclusions: The Conners indexes may be considered reliable and valid instruments for detecting ADHD symptoms in Spanish populations.

Keywords: Conners, ADHD, School population, Psychometric properties, Descriptive survey study

Resumen

Ante#cedentes/Obj#etivo: Analizar las propiedades psicométricas del Conners 3 ADHD Index (Conners 3 AI) y del Conners Early Children Global Index (Conners ECGI), en sus formas para padres (PF) y maestros (TF), en escolares españoles. Método: Estudio transversal en doble fase. En la primera fase, se recogió información de maestros (n = 1.796) y padres (n = 882) de niños de 4-5 y 10-11 años. En la segunda fase (n = 196), se evaluaron individualmente niños a riesgo de TDAH y controles. Resultados: Se confirmó la estructura bifactorial del Conners 3 AI, que agrupa síntomas de hiperactividad-impulsividad e inatención, y del Conners ECGI PF, que agrupa síntomas labilidad emocional e inquietud-impulsividad. A diferencia de la versión original, el Conners ECGI TF presentó un factor adicional de inatención. La evidencia de validez convergente con el Child Behavior Checklist y la Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders & Schizophrenia, y de validez con criterios externos (rendimiento académico) fueron entre moderadas y altas. Se encontraron puntuaciones significativamente más altas en los niños que en las niñas para ambos índices. Las puntuaciones directas correspondientes a puntuaciones T clínicas fueron más elevadas que en la versión original. Conclusiones: Los Índices de Conners pueden considerarse instrumentos válidos y fiables para detectar sintomatología de TDAH en población española.

Palabras clave: Conners, ADHD, población escolar, propiedades psicométricas, estudio descriptivo por encuesta

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the most commonly diagnosed neurodevelopment disorder in children and adolescents. Recent international and national meta-analyses have estimated ADHD prevalence to be around 7% in children and adolescents from non-clinical populations (Català-López et al., 2012, Thomas et al., 2015). Among preschoolers, a prevalence of between 2% and 5% has been described (Canals et al., 2016, Ezpeleta et al., 2014, Gudmundsson et al., 2013, Wichstrøm et al., 2013).

The use of validated screening tools in primary health care and school is commonly recommended to improve the identification of psychopathology in the general child population. In ADHD detection, clinical guidelines encourage professionals to collect behaviour information on the child in multiple environments, especially in the family and at school (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, AACAP, 2007; American Academy of Pediatrics, AAP, 2011; Grupo de Trabajo de la Guía de Práctica Clínica, GPC, 2010; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, NICE, 2016). This is necessary because parents and teachers can often show different views about the child's behaviour due to the environment in which the child is evaluated. Specifically, hyperactive-impulsive symptoms appear to be more consistently reported by both informants than inattentive symptoms (Narad et al., 2015).

For this purpose, behaviour rating scales based on Diagnostic Statistical Medical, DSM (American Psychiatric Association, APA, 2013) or CIE-10 (World Health Organization, WHO, 1992) criteria are recommended and commonly used by neuro-paediatricians and clinical and school psychologists when academic or behaviour problems and symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, or impulsivity are referred in children These questionnaires tend to be brief and categorical, such as the SNAP-IV (Swanson et al., 2001) or the ADHD Rating scale IV (DuPaul et al., 1998).

The Conner's rating scales (Conners, 1989, Conners, 1997, Conners, 2009) provide a dimensional assessment of the child behavior, such as inattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity, learning problems, executive functioning, aggression and peer relations. The several forms of the questionnaire are widely used in many countries as screening and follow-up tools. In Spain, validations of these scales have been performed by several authors with good results (Amador et al., 2003, Amador et al., 2002, Farre-Riba and Narbona, 1997). The new versions of the Conners Early Childhood Global Index (Conners EC GI; Conners, 2009) and the Conners 3 ADHD Index (Conners 3 AI; Conners, 2008) are reliable instruments for detecting ADHD problems in children aged 2 to 6 and 6 to 18 years old, respectively. Both questionnaires load the 10 highest items from the original and revised Conners Parent and Teacher Rating Scales (Conners, 1989, Conners, 1997). The Spanish validations of the Conners 3 AI and the Conners EC GI have been conducted in a Hispanic American population (Conners, 2008, Conners, 2009), but we do not have data on the psychometric properties in a Spanish population. In this context, Arias Martínez, Arias González, & Gómez Sánchez, 2013 conducted a calibration of Conners 3 AI with Rasch’ model on a sample of 5 to 6 year old children. Although this was lower that the recommended age, the results indicated good psychometric properties and a floor effect in children with low levels of hyperactivity.

Given that Conners scales are widely used instruments in clinical practice, the aim of this study was to assess the psychometric properties of the Conners 3 AI and the Conners EC GI parents’ and teachers’ forms in a Spanish school population. The specific aims were 1) to assess reliability obtaining the overall accuracy and inter-rater consistency of the scale, 2) to find evidence of the internal structure, 3) to find evidence of convergent and external validity, and 4) to describe the mean scores of the scales by gender and grade. Using the results obtained by the questionnaire's authors and other studies conducted with Spanish samples, we expect to find a high internal reliability but a low inter-rater agreement between parents and teachers, higher scores for boys and in parent reports, and a two-dimensional factor structure in both scales and forms. With regard to evidence of convergent and external validity, the hypothesis was to find a high correlation with other ADHD measures and the child's school performance.

Method

Participants

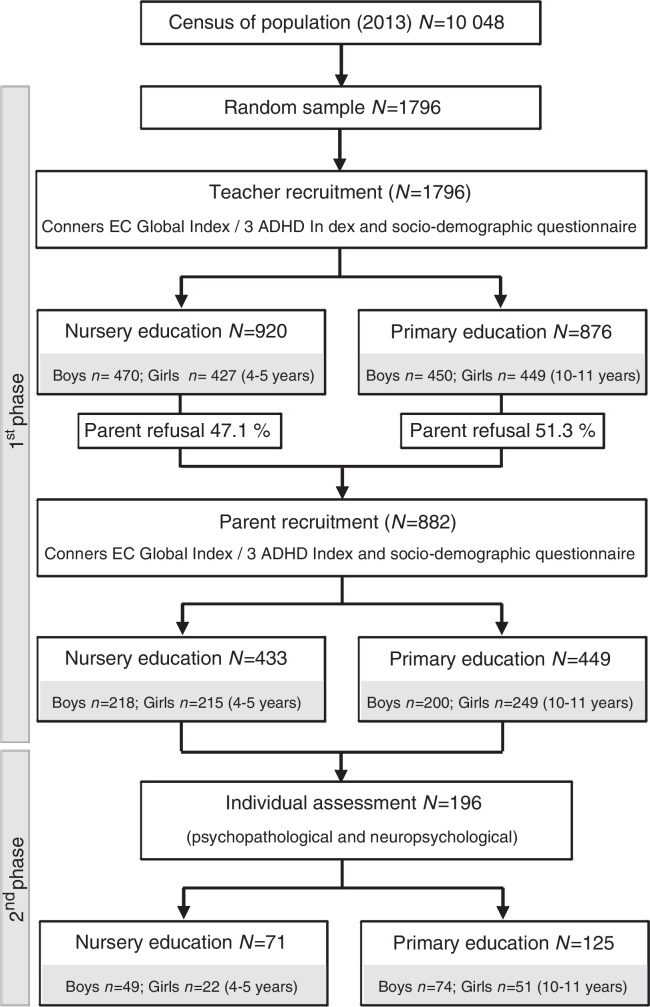

The sample was obtained through the Neurodevelopmental Disorders Epidemiological Research Project (EPINED). The project is studying a representative sample of two age groups: 3,500 children from Nursery Education (NE, 4-5 years) and 3,500 from Primary Education (PE, 10-11 years) in order to determine the prevalence of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and ADHD in Tarragona, Spain. The study design and the participants by grade and gender status are disclosed in figure 1. In the first phase, the sample contained 1,796 children: 876 school aged children (M= 10.96; SD= 0.44) and 920 preschool aged children (M= 4.93; SD= 0.41). Of these children, 14.9% belong to low socioeconomic status (SES), 63.6% to middle SES and 21.5% to high SES; 74.1% of the sample was born in Spain. In the second phase (n= 196), children at risk for ADHD and controls were individually assessed and parents were interviewed. No significant differences in sociodemographic variables were found between the first and second phase samples.

Figure 1.

Study design and participants.

Instruments

The Conners EC Global Index is a 10-item scale that assesses the presence of general psychopathology over the last month in children between 2 and 6 years. This scale is part of the Conners Early Childhood (Conners, 2009), but it also can be administered independently. Items are scored on a four-point Likert scale and divided into two subscales that assess symptoms related to ADHD: restless-impulsive and emotional lability. The scale has a cut-off for elevated scores (T 65-69) and for very elevated scores (T ≥70), indicating more and many more concerns, respectively, than typically reported in children. The parents’ and teachers’ forms have shown a high internal reliability (Cronbach's alpha), with values of .89 and .92 respectively. The restless-impulsive’ subscale has an internal reliability of .87 in the parents’ form and .91 in the teachers’ form, while the emotional lability subscale ranged between .75 and .86, respectively. Inter-rater agreement is .75 (p=.001) for the total scale, .75 (p=.001) for the restless-impulsive subscale and .62 (p=.001) for the emotional lability subscale.

The Conners 3 ADHD Index (Conners’ Hyperactivity Index) is a 10-item scale that assesses the presence of the most prominent symptoms of ADHD over the last month in children between 6 and 18 years. This scale is part of the Conners Rating Scale 3rd Edition (Conners, 2008), but it also can be administered independently. The authors recommend the use of this index as a research and clinical screening tool in large samples. Items are based on DSM-5 criteria and scored on a four-point Likert scale. The scale has a cut-off for elevated scores (T 65-69) and for very elevated scores (T ≥70). Parents’ and teacher’ forms have shown a high internal reliability, with values of .90 and .93 respectively. Inter-rater agreement is.56 (p=.001).

The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Aged Children (K-SADS-PL; Kaufman et al., 1997) is a semi-structured psychiatric interview that yields DSM diagnoses and has been widely used in studies of child psychopathology. We used the K-SADS-PL to collect information on child ADHD symptomatology from parents. The Spanish version has shown a high inter-rater reliability (K = .91) for the ASD scale (Ulloa et al., 2006).

The Child Behavior Checklist is a parent report to assess psychopathological symptoms among preschoolers (CBCL 1½-5; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) and school-aged children (CBCL 6-18, Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). CBCL 1½-5 has a list of 110 items of behavioural problems that provided scores for seven scales; emotionally reactive, anxious/depressed, somatic complaints, withdrawn, sleep problems, attention problems and aggressive behavior. CBCL 6-18 has a list of 113 items of behavioral problems that provided scores for eight scales; anxious/depressed, withdrawn/depressed, somatic complaints, social problems, thought problems, attention problems, rule-breaking behavior and aggressive behavior. Both questionnaires provide DSM scales. In the preschool form, De la Osa, Granero, Trepat, Domenech, and Ezpeleta (2016) reported an internal reliability between .65 and .86 for the syndrome scales and .50 and .78 for the DSM-5 scales. The internal reliability of the Spanish school-aged version ranged from .71 to .87 (Sardinero, Pedreira, & Muñiz, 1997).

The academic achievement was recruited by latest school marks and used to obtain teacher qualitative and quantitative reports. Among preschoolers, school marks were coded as low (1), medium (2) and high (3) achievement in self-care, social interaction, motor skills, science, art, mathematics and language. Among school-aged children, school ratings included motor skills, science, art, mathematics, language and foreign language. School marks were coded as insufficient, sufficient, good, very good and excellent and ranged from 0 to 10. The mean score of all the school marks was calculated to obtain the child global achievement.

A sociodemographic questionnaire addressed to parents and teachers was developed ad-hoc in order to gather information during the first phase from the children (age, gender, place of birth and previous diagnosis) and their families (place of birth, educational level and parents’ work and marital status). Socioeconomic level was estimated according to Hollingshead.

If any items were missing from any of the questionnaires administered and they did not amount to more than 10% of the total, we imputed data on the basis of responses to similar items.

Procedure

According to the classification of Montero and León (2007), this was a descriptive survey study. The EPINED is a double phase epidemiologic cross-sectional initiated in 2013 in Tarragona (Spain). Before beginning the study, we obtained permission from the Catalan Department of Education and the Ethics Committee at the Sant Joan University Hospital (Reus). All the school boards contacted agreed to participate in the study.

Through the teachers, we sent to all the families a letter informing them about the study and asking for their written informed consent. The participation was voluntary and disinterested. The assessment procedure was conducted by a research group from the Rovira i Virgili University consisting of psychology and medicine professionals specialized in child and adolescent psychopathology. Individual assessments of the child and family interviews were conducted in the schools in order to facilitate participation.

In the first phase, socio-demographic data from all 1,796 children were collated and Conners EC GI and Conners 3 AI were completed by parents and teachers in order to assess ADHD symptoms and identify children at risk of the disorder. An agreement with the Catalan Department of Education allowed us to collect anonymous data from teachers about the children of non-participating families, obtaining data from the whole sample. A total of 49.1% of the families agreed to participate in the study and signed the written informed consent. Thus, information from both informants (teacher and family) was obtained of 882 children (see figure 1).

We considered children to be at risk of ADHD if they obtained a T-score ≥ 65 from both informants. This cut-off score was chosen to include all the subjects with elevated and very elevated scores (Conners, 2008, Conners, 2009). In the second phase, parents of subjects at risk of ADHD and a subsample without risk (controls) answered the CBCL and were assessed using K-SADS-PL ADHD. Academic achievement was also recruited. Diagnosis was performed in accordance with DSM-5 criteria and by means of an individual neuropsychological and psychopathological assessment of the child and its family. All the families agreed to participate in this phase and received a complete report of the results.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic characteristics of the sample and the average score for the different age groups and forms. Factorial analysis (FA) was used to obtain the factor structure of the Conners 3 AI and Conners EC GI. An Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted on a randomly selected half of the sample. On the second half, a Semi-Confirmatory Factor Analysis (S-CFA) was performed using a semi-specified target matrix. Finally, the same S-CFA was replicated with the whole sample. For all the FA, we used an optimal implementation of Parallel Analysis (Timmerman & Lorenzo-Seva, 2011), an unweighted least squares’ extraction method and, to obtain an oblique rotated solution, we used the direct oblimin procedure (Browne, 1972). Polychoric correlation dispersion matrices were used because of the ordinal nature of the data and because several items showed skewness or kurtosis greater than one in absolute values. For the S-CFA solution, three commonly recommended fit indices were used: the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), the root mean square of the residuals (RMSR) and the congruence index. As Lorenzo-Seva and ten Berge (2006) suggest, congruence values in the range .85-.94 were interpreted as correspondent with a fair similarity and values higher than .95 were interpreted as implies that the two factors (or components) compared can be considered equal. The evidence of convergent and external validity was computed by Pearson correlations and evidence of the internal reliability of the overall scales and factors was assessed using the reliability estimates of the factor scores, which take into account the ordinal nature of the item responses. To assess the reliability of the overall scale, the first canonical factor was extracted (Ferrando & Lorenzo-Seva, 2013) and its reliability estimate was obtained.

Statistical analyses were performed by SPSS 22.0 and FAs and internal reliabilities were conducted using FACTOR 9.2 (Lorenzo-Seva & Ferrando, 2013).

Results

All the socio-demographic and psychopathological data are shown in table 1. In the first phase there were no significant differences in age, gender, ethnicity or SES between participating and non-participating families. In the second phase, there were significantly more boys than girls in Nursery (z = 2.79, p = .005) and Primary Education (z = 2.09, p = .004).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

| FIRST PHASE (N = 1,796) |

SECOND PHASE (N = 196) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher recruitment |

Parent recruitment |

|||||

| NE (N = 920) | PE (N = 876) | NE (N = 433) | PE (N = 449) | NE (N = 71) | PE (N = 125) | |

| Age: m (SD) | 4.95 (0.42) | 10.93 (0.47) | 4.93 (0.41) | 10.96 (0.44) | 4.95 (0.38) | 11.02 (0.41) |

| Gender, male, n (%) | 470 (51.09) | 427 (48.74) | 218 (50.34) | 200 (44.54) | 49 (69.01) | 74 (59.20) |

| Ethnicity, autochthonous, n (%) | 682 (74.13) | 729 (83.22) | 356 (82.22) | 378 (84.18) | 58 (81.69) | 105 (84.00) |

| Socioeconomic status, n (%) | ||||||

| Low | 137 (14.92) | 190 (27.70) | 66 (15.24) | 97 (21.57) | 12 (16.39) | 24 (19.64) |

| Middle | 585 (63.61) | 545 (62.26) | 272 (62.83) | 275 (61.17) | 45 (63.94) | 83 (66.08) |

| High | 198 (21.47) | 141 (16.04) | 95 (21.93) | 77 (17.26) | 14 (19.67) | 18 (14.29) |

| ADHD risk T ≥ 65, n (%) | ||||||

| Conners teacher | 68 (7.39) | 198 (22.60) | 29 (6.70) | 97 (21.60) | 22 (30.99) | 68 (54.40) |

| Conners parent | - | - | 164 (37.88) | 178 (39.64) | 45 (63.38) | 79 (63.20) |

| K-SADS, m (SD) | ||||||

| Inattentive | - | - | - | - | 4.35 (5.01) | 7.43 (6.35) |

| Hyperactive-impulsive | - | - | - | - | 5.28 (5.83) | 5.07 (5.42) |

| Total score | - | - | - | - | 9.63 (10.20) | 12.50 (10.68) |

| CBCL | ||||||

| ADHD DSM scale | - | - | - | - | 62.85 (8.69) | 59.88 (8.80) |

| Internalizing problems | - | - | - | - | 62.65 (11.71) | 58.42 (10.97) |

| Externalizing problems | - | - | - | - | 61.79 (12.37) | 54.61 (11.44) |

| Total problems | - | - | - | - | 64.49 (12.41) | 57.74 (11.44) |

| Academic achievementa | - | - | - | - | 2.29 (0.57) | 6.42 (0.97) |

| Total Wechsler IQ, m (SD) | - | - | - | - | 97.37 (16.08) | 98.19 (16.31) |

| ADHD diagnoses, n (%) | - | - | - | - | 12 (16.90) | 47 (37.60) |

| Other NDD diagnoses, n (%)b | - | - | - | - | 11 (15.49) | 7 (5.60) |

| Controls, n (%)c | - | - | - | - | 48 (67.61) | 71 (56.80) |

Note. NE: Nursery Education; PE: Primary Education. Mean (m) and standard deviation (SD) or percentage (n; %).

Academic achievement ranged from 1 to 3 in NE and from 0 to 10 in PE.

Other neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD) include: autism spectrum disorders, tic disorders (including Tourette disorder), obsessive- compulsive disorder, oppositional defiant disorder and specific learning disorders.

Control group included children who did not present any psychopathological diagnosis.

We acknowledge the support of the Catalan Department of Education. We are indebted to all participating teachers and families involved in the EPINED project.

Evidence of internal structure validity of the Conners EC GI and Conners 3 AI

Factor analysis of the Conners EC GI and Conners 3 AI was conducted to test the invariance across gender. The results indicate the same evidence of internal structure in boys and girls. Thus, global analyses were performed and the results are described below.

EFA was conducted on half of the total NE sample using the Conners EC GI forms for teachers (n=460) and parents (n=216). As the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) index values were .86 (TF) and .88 (PF), we concluded that the correlation matrix was suitable for factor analysis. The root mean square of residuals (RMSR) was .019 (Kelly criterion=.047) for the TF and .038 (Kelly criterion=.068) for the PF. Results suggested that the data had an underlying three-dimensional factor structure for the TF and a two-dimensional factor structure for the PF. S-CFA was conducted on the other half of the sample by means of a semi-specified target matrix that was suitable to be factorized (KMOTF=.88; KMOPF=.89) using all the items of each factor as markers. The results confirmed the factorial structure found in the EFA (RMSRTF=.021, Kelly criterion=.047; RMSRPF=.042, Kelly criterion=.068). The congruence of the items, factors and total ranged from .88 to 1.00. We then performed the analysis on the total sample (see table 2).

Table 2.

Factor structure of the Conners EC GI.

| Teacher Form Factors | Parent Form Factors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restless- impulsive | Emotional lability | Inattentive | Restless- impulsive | Emotional lability | ||

| Restless | .98 | .02 | -.13 | .95 | -.23 | |

| Impulsive | .78 | .25 | -.07 | .80 | -.06 | |

| Fidgeting | .94 | -.04 | .06 | .87 | -.13 | |

| Disturbs | .67 | .09 | .19 | .45 | .08 | |

| Temper outbursts | .21 | .78 | -.05 | .15 | .61 | |

| Easily frustrated | .10 | .76 | -.01 | .26 | .41 | |

| Cries often and easily | -.08 | .66 | -.00 | -.13 | .81 | |

| Mood changes | .02 | .87 | .03 | .00 | .72 | |

| Fails to finish | -.20 | .07 | .96 | .45 | .13 | |

| Inattentive | .27 | -.11 | .73 | .47 | .15 | |

| Congruence of factors | .96 | .97 | .96 | .93 | .93 | |

| Explained variance (%) | .64 | .11 | .07 | .56 | .12 | |

| Factor’ reliability (ordinal alpha) | .91 | .96 | .882 | .90 | .83 | |

| Matrix statistics | Bartlett's statistic | 5171.9 (df= 45 p= .001) | 1597.4 (df= 45 p= .001) | |||

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) index | .87 | .89 | ||||

| Residuals statistics | Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Root Mean Square for Residuals (RMSR) | .019 | .036 | ||||

| Kelley's criterion | .033 | .048 | ||||

We obtained three factors in the TF (restless-impulsive, emotional lability and inattentive) that explained 83.3% of the variance. Two factors in the PF (restless- impulsive and inattentive) explained the 69.0% of the variance. In general, factor loading ranged from .45 to .99. The items showed a fair level of congruence ranging from .84 to 1.00.

EFA was also conducted on half of the total PE sample using the Conners 3 AI forms for teachers (n=438) and parents (n=226). KMO index values were .92 (TF) and .90 (PF) and the RMSR was .033 (Kelly criterion=.048) for the TF and .032 (Kelly criterion=.067) for the PF. A S-CFA was applied to the other half of the sample using all the items of each factor as markers and a semi-specified target matrix that was suitable to be factorized (KMOTF=.93; KMOPF=.90). The results confirmed the factorial structure found in the EFA (RMSRTF=.027, Kelly criterion=.048; RMSRPF=.037, Kelly criterion=.067). The congruence of the items, factors and total ranged from .93 to 1.00. We then performed the analysis on the total sample (see table 3).

Table 3.

Factor structure of the Conners 3 AI.

| Teacher Form Factors | Parent Form Factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperactive - impulsive | Inattentive | Hyperactive- impulsive | Inattentive | ||

| Squirms in seat | .85 | .11 | |||

| Restless | .99 | -.16 | |||

| Impulsive | .77 | .14 | |||

| Easily distracted | .17 | .80 | |||

| Sidetracked easily | .08 | .79 | |||

| Fails to complete tasks | -.13 | .96 | |||

| Avoids tasks that require effort | -.09 | .93 | |||

| Does not seem to listen | -.01 | .90 | |||

| Does not focus | .07 | .88 | |||

| Inattentive | .11 | .86 | |||

| Fidgeting | .88 | -.06 | |||

| Squirms in seat | .71 | .09 | |||

| Restless | .99 | -.18 | |||

| Interrupts | .01 | .79 | |||

| Does not seem to listen | .09 | .81 | |||

| Doesn’t pay attention to details | -.06 | .88 | |||

| Inattentive | -.13 | .91 | |||

| Disorganized | -.04 | .82 | |||

| Gives up tasks | .11 | .74 | |||

| Easily distracted | .28 | .48 | |||

| Congruence of factors | .97 | .99 | .91 | .96 | |

| Explained variance (%) | .104 | .76 | .11 | .62 | |

| Factor’ reliability (ordinal alpha) | .98 | .97 | .93 | .93 | |

| Matrix statistics | Bartlett's statistic | 8203.2 (df= 45 p= .001) | 2686.9 (df= 45 p= .001) | ||

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) index | .92 | .90 | |||

| Residual statistics | Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Root Mean Square for Residuals (RMSR) | .023 | .031 | |||

| Kelley's criterion | .034 | .047 | |||

The results suggested that both forms had an underlying two-dimensional factor structure (hyperactive-impulsive and inattentive). Factor loading ranged from .48 to .99 and the items showed a fair level of congruence ranging from .97 to 1.00, with the exception of the item “Interrupts others”, which showed a congruence value of .45 and load in the inattentiveness factor. This item was factorially complex because, in the EFA and S-CFA, loaded in both factors and we included it in the hyperactive-impulsive factor due to its clinical significance. When the analysis was replicated in the total sample, the loading of the item was higher in the inattentive factor but we maintained it in the hyperactive-impulsive factor.

Reliability measures of the Conners 3 AI and Conners EC GI

The overall scale internal reliabilities (ordinal alpha) for Conners EC GI were .92 for PF and .97 for TF; and for the Conners 3 AI they were .96 for PF and .98 for TF. Reliability values (ordinal alpha) for both forms and factors are shown in Table 1, Table 2. In general, teachers’ forms obtained higher values for both scales and most of the factors. The internal reliability of the Conners 3 AI was higher than the Conners EC GI. Inter-rater agreement (Cohen's kappa) was moderate for the Conners EC GI (K=.44, p=.001) and the Conners 3 AI (K=.50, p=.001). The factors’ inter-rater agreement ranged from weak to moderate among preschoolers (Restless-impulsive: K=.43, p=.001; Emotional lability: K=.27, p=.001) and school-aged children (Hyperactive-impulsive: K=.35, p=.001; Inattentive: K=.51, p=.001).

Evidence of convergent and external validity of the Conners EC GI and Conners 3 AI

Academic achievement was used to assess external validity (table 4). In general, the teacher's Conners scores were best correlated with the school marks, being the inattentive factor the most correlated with the child global achievement (Conners EC GI r=-.50, p=.004; Conners 3 AI r=-.52, p=.001). Taking into account the different subjects and skills assessed, the inattentive factor showed a higher relation with self-care (r=-.51, p=.001), art (r=-.50, p=.001) and mathematics (r=-.47, p=.001) among preschoolers and language (native r=-.48, p=.001; foreign r=-.46, p=.001), art (r=-.51, p=.001) and mathematics (r=-.50, p=.001) among school-aged children. The total score of the Conners 3 AI, including inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive symptoms, also revealed moderate correlations with the total academic achievement in older children.

Table 4.

Evidence of external and convergent validity of the Conners EC GI and the Conners 3 AI.

| Conners EC Global Index |

Conners 3 ADHD Index |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher’ Form |

Parents’ Form |

Teacher’ Form |

Parents’ Form |

||||||||||

| IN | RI | EL | TOT | RI | EL | TOT | IN | HI | TOT | IN | HI | TOT | |

| r | r | r | r | r | r | r | r | r | r | r | r | r | |

| Academic achievement | |||||||||||||

| Self-care | -.51** | -.35** | -.38** | -.44** | -.45** | -.26* | -.40** | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Social interaction | -.38** | -.23 | -.38** | -.35** | -.35** | -.21 | -.32** | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Motor skills | -.30* | -.22 | -.22 | -.30* | -.21 | -.00 | -.13 | -.26** | -.04 | -.22* | -.20* | -.24** | -.22** |

| Science | -.33* | -.23 | -.22 | -.33* | -.36** | -.22 | -.33* | -.40** | -.21* | -.38** | -.38** | -.32** | -.37** |

| Art | -.49** | -.32** | -.33** | -.41** | -.37** | -.15 | -.30** | -.51** | -.19* | -.46** | -.30** | -.30** | -.31** |

| Mathematics | -.47** | -.19 | -.34** | -.34** | -.38** | -.17 | -.32** | -.44** | -.14 | -.39** | -.29** | -.24** | -.28** |

| Language | -.31** | -.08 | -.22 | -.20 | -.32** | -.20 | -.30* | -.47** | -.26** | -.45** | -.33** | -.26** | -.31** |

| Foreign language | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -.45** | -.20* | -.42** | -.28** | -.26** | -.28** |

| Average achievement | -.50** | -.28* | -.42** | -.42** | -.44** | -.22 | -.38** | -.52** | -.23** | -.48** | -.37** | -.32** | -.36** |

| Psychopathological measures | |||||||||||||

| K-SADS ADHD | |||||||||||||

| Inattentive factor | .48** | .63** | .58** | .65** | .58** | .39** | .55** | .48** | .38** | .50** | .66** | .63** | .67** |

| Hyperactive-impulsive factor | .45** | .58** | .42** | .56** | .71** | .38** | .62** | .45** | .42** | .49** | .61** | .64** | .64** |

| Total score | .49** | .64** | .53** | .64** | .69** | .41** | .63** | .52** | .44** | .54** | .70** | .70** | .72** |

| CBCL scales | |||||||||||||

| ADHD DSM scale | .25* | .41** | .23* | .35** | .62** | .43** | .60** | .50** | .43** | .52** | .71** | .77** | .76** |

| Internalizing problems | .19 | .17 | .18 | .20 | .38** | .51** | .49** | .10 | .05 | .09 | .42** | .46** | .45** |

| Externalizing problems | .25* | .46** | .32** | .41** | .695* | .58** | .71** | 41** | .39** | .41** | .69** | .70** | .72** |

| Total problems | .26* | .30* | .24* | .30** | .57** | .57** | .64** | .32** | .25** | .33** | .69** | .70** | .71** |

Note. IN: Inattentive; RI: Restless-impulsive; EL: Emotional lability; HI: Hyperactive-impulsive; TOT: Total. **p<.01; *p<.05.

Evidence of convergent validity was evaluated between Conners indexes and K-SADS-PL and CBCL scores. The Conners EC GI and 3 AI parents’ and teachers’ showed moderate to high correlations with the K-SADS-PL ADHD total score between .55 and.73 (p=.001). Regarding prescholers, the hyperactive factor, in both parents’ and teachers’ scores, was the most correlated with all K-SADS-PL factors. In regard to school-aged children, the parents’ form presented higher correlations than the teachers’ form for each factor and total score. The CBCL forms showed a lower convergence with the Conners indexes, being parents’ scores the most correlated with both questionnaires. In this sense, the higher correlations were found between parents’ scores in all Conners EC GI and 3 AI factors and CBCL ADHD DSM scale, externalizing and total problems (between .60 and .76, p=.001).

Mean scores and standardized scores of the Conners EC GI and Conners 3 AI

Descriptive data for factors and total scores in teacher and parents’ forms are shown in table 5. Significantly higher scores (p≤ .003) were found in boys, compared with girls, in all factors and total scores for the Conners EC GI and the Conners 3 AI. In general all the differences were associated with high effect size (eta squared values ranging from .22 to .58). The only exception was found in the emotional lability scores among preschoolers, where no differences (p=.462) were observed by gender. Parents’ scores were also significantly higher (p≤ .007) than teacher's scores in all factors and total scores.

Table 5.

Conners EC GI and Conners 3 AI’ mean scores and compared by gender.

| Teachers’ form |

Parents’ form |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Boys | Girls | p | Partial Eta Square | Total | Boys | Girls | p | Partial Eta Square | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||||

| Conners EC GI | ||||||||||

| Inattentive | 1.23 (1.44) | 1.49 (1.54) | 0.96 (1.28) | .001 | .033 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Hyperactive- Impulsive or Restless-impulsive | 2.41 (2.98) | 3.12 (3.28) | 1.67 (2.43) | .001 | .055 | 6.82 (3.95) | 7.63 (3.96) | 6.00 (3.78) | .001 | .043 |

| Emotional lability | 1.53 (1.87) | 1.43 (2.12) | 0.87 (1.52) | .001 | .022 | 4.42 (2.92) | 4.52 (2.94) | 4.31 (2.90) | .462 | .001 |

| Total score | 4.79 (5.25) | 6.03 (5.78) | 3.50 (4.28) | .001 | .058 | 11.23 (6.19) | 12.15 (6.30) | 10.31 (5.95) | .002 | .058 |

| Conners 3 AI | ||||||||||

| Inattentive | 1.76 (3.36) | 2.56 (4.08) | 0.99 (2.25) | .001 | .048 | 2.68 (3.37) | 3.22 (3.70) | 2.25 (3.02) | .003 | .020 |

| Hyperactive- Impulsive or Restless-impulsive |

0.49 (1.24) | 0.78 (1.54) | 0.21 (0.77) | .001 | .044 | 1.74 (2.16) | 2.19 (2.47) | 1.38 (1.80) | .001 | .035 |

| Total score | 2.24 (4.22) | 3.33 (5.41) | 1.20 (3.63) | .001 | .057 | 4.42 (5.28) | 5.14 (5.95) | 2.73 (4.54) | .001 | .027 |

Raw scores and Percentiles (Pc) obtained from the Conners EC GI and 3 AI forms are shown separately by gender (see table 6). We highlight the scores for Pc 93-97 and Pc ≥ 98, corresponding to the cut-off for elevated scores (T 65-69) and for very elevated scores (T ≥ 70), respectively.

Table 6.

Conners EC GI and Conners 3 AI’ raw scores and percentiles by gender.

| Pc | Conners EC GI |

Conners 3 AI |

Pc | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teachers’ Form |

Parents’ Form |

Teachers’ Form |

Parents’ Form |

||||||||||

| Boys | Girls | Total | Boys | Girls | Total | Boys | Girls | Total | Boys | Girls | Total | ||

| 99 | 25 | 22 | 23 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 20 | 16 | 19 | 20 | 16 | 19 | 99 |

| 98 | 22 | 17 | 21 | 27 | 25 | 26 | 19 | 12 | 16 | 19 | 15 | 18 | 98 |

| 97 | 20 | 14 | 18 | 26 | 23 | 24 | 17 | 9 | 15 | 19 | 15 | 17 | 97 |

| 96 | 18 | 13 | 17 | 24 | 22 | 24 | 16 | 8 | 14 | 18 | 15 | 16 | 96 |

| 95 | 18 | 12 | 16 | 24 | 21 | 23 | 15 | 7 | 13 | 17 | 14 | 15 | 95 |

| 94 | 17 | 11 | 15 | 24 | 21 | 23 | 14 | 5 | 12 | 17 | 14 | 15 | 94 |

| 93 | 16 | 10 | 14 | 23 | 20 | 22 | 14 | 5 | 11 | 16 | 13 | 15 | 93 |

| 90 | 14 | 9 | 12 | 22 | 18 | 20 | 12 | 4 | 8 | 15 | 11 | 14 | 90 |

| 80 | 11 | 6 | 8 | 17 | 16 | 16 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 12 | 7 | 9 | 80 |

| 70 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 15 | 13 | 14 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 70 |

| 60 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 13 | 11 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 60 |

| ≤ 50 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 50 |

Note. Cut-off points for elevated (Pc 93-97) and very elevated scores (Pc ≥ 98) are highlighted.

Discussion

Conners 3 AI and EC GI have shown good psychometric properties in both parents’ and teacher’ forms. To our knowledge, no studies have been conducted to validate the psychometric properties of the new Conners indexes in different cultures. Some studies have been conducted on Spanish populations with previous versions (Amador et al., 2003, Amador et al., 2002, Farre-Riba and Narbona, 1997), but data for the latest version were not available. Due to their briefness and efficacy in ADHD detection, these scales seem to be appropriate for screening procedures in primary health care, school and research settings.

Factor analysis produced clearly defined and easily labelled factors in accordance with the clinical consistency of the items. Given the statistical indicators, we found high item-factor correlations and a good explained variance of the models, ranging from .62 to .83. As has been previously described in the original North American validated version, in the Conners 3 AI forms, we found two underlying factors corresponding with inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive symptoms. Arias Martínez et al. (2013) obtained similar results for the parents’ form in a Spanish population. Although they consider the scale as “unidimensional enough”, we contemplate the two factor structure based on statistical and clinical criteria. Our results also confirm the two factor structure regarding emotional lability and restless-impulsive symptoms of the Conners EC GI parents’ forms. However, in the teachers’ form we also found a third factor that computed those items that assessed inattentive symptoms, which suggests that inattention could be identified by teachers as an early indicator of ADHD.

The Conners indexes have shown good consistency in our sample. The internal reliabilities were excellent in all the overall scales and factors (ordinal alpha values ranging from .84 to .98). Of all the responses, the teachers’ were the most reliable. These results are similar to those obtained in the original validation (.75-.93), where higher values were also obtained in the teachers’ forms (Conners, 2008, Conners, 2009). Previous versions of the scales have also demonstrated a similar and high internal reliability in a Spanish community (.92) and clinical (.87) samples (Amador et al., 2003). Parent-teacher agreement (Cohen's kappa) values were moderate; results were close to the original values in the Conners 3 AI, but were much lower in the Conners EC GI. However, inter-rater agreement was within the .09–.43 range compiled by Narad et al. (2015) from studies on ADHD symptoms across development.

Regarding the evidence of external validity, our data showed that ADHD symptoms interfere with the academic achievement in all age group. The inattentive factor was most associated with academic achievement. Similar relationships have been found in previous studies (González-Castro et al., 2015, Papaioannou et al., 2016, Scholtens et al., 2013) supporting the idea that teachers are good at detecting symptoms of inattention in its early stages. In fact, early intervention on ADHD core symptoms has shown to improve school performance in children (Arnold et al., 2015, Moreno-García et al., 2015).

The Spanish forms of the Conners indexes showed moderate to high correlations with K-SADS-PL and CBCL scores, although our results were lower than the original versions. In regard to Conners EC GI, correlations between parents’ form and CBCL ADHD scale, externalizing scale and total score ranged from .43 to .72 in comparison to the original values that ranged from .56 to .93 (Conners, 2009). In relation to Conners 3, the original version only compared the whole scale with CBCL scores and this could explain that their correlations were higher (from .63 to .89) than those obtained in the present study. On the other hand, we didn’t administer the Teacher Report Form and this reason may explain the lowest correlations in teacher’ forms.

In keeping with previous research, mean scores of the Conners indexes were significantly higher among boys (with a high effect size ranging from 0.22 to 0.58) and on parents’ forms (Català-López et al., 2012, Conners, 2008, Conners, 2009, Ezpeleta et al., 2014, Narad et al., 2015, O’Neill et al., 2014, Wichstrøm et al., 2013). With regard to percentiles, our scores were higher than the values described in the original version. Raw scores obtained at Pc 98 (T-score ≥ 70) in Conners 3 AI were 16 (TF) and 18 (PF), while the original version describes values of 13 and 6, respectively. Minor differences were observed in the Conners EC GI original version, which describes values of 22 and 20, respectively whereas we obtained 21 (TF) and 26 (PF). This may be due to cultural differences in children's behavior and the informants’ perceptions.

In summary, our results indicate that Conners 3 AI and EC GI are valid questionnaires for the detection of inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive symptoms in children from a non-clinical population. In this sense, the use of these short indexes would improve ADHD screening procedures both in clinical and school settings. However, the present study does have some limitations. Firstly, we consider that replications in larger samples along with an additional statistical analysis (such as ROC curves) should be carried out in order to establish the accuracy, sensitivity and specificity of the Conners indexes and to determine the optimal cut-off points. Also, it would be interesting to carry out validation studies in clinical population.

Funding

This study was funded by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness of Spain and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF; ref. PSI2015-64837-P). The sponsor of the study had no role in the study design, data gathering, data analysis, and data interpretation, or writing of the report. It was also supported by the Ministry of Education of Spain (grant FPU2013-01245).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of the Catalan Department of Education. We are indebted to all participating teachers and families involved in the EPINED project.

References

- Achenbach T.M., Rescorla L.A. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; Burlington, VT: 2000. Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms & Profiles. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T.M., Rescorla L.A. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; Burlington, VT: 2001. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. [Google Scholar]

- Amador J.A., Idiázabal M.A., Aznar J.A., Peró M. Estructura factorial de la Escala de Conners para profesores en muestras comunitaria y clínica. Revista de Psicología General y Aplicada. 2003;56:173–184. [Google Scholar]

- Amador J.A., Idiázabal M.A., Sangorrín J., Espadaler J.M., Forns M. Utilidad de las escalas de Conners para discriminar entre sujetos con y sin trastorno por déficit de atención con hiperactividad. Psicothema. 2002;14:350–356. [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, AACAP Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:894–921. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318054e724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics, AAP ADHD: Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011;128:1–16. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, APA . 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; Arlington, VA: 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Arias Martínez B., Arias González V.B., Gómez Sánchez L.E. Calibration of Conners ADHD Index with Rasch Model. Universitas Psychologica. 2013;12:957–970. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, L.E., Hodgkins, P., Kahle, J., Madhoo, M., & Kewley, G. (2015). Long-Term Outcomes of ADHD Academic Achievement and Performance. Journal of Attention Disorders. doi: 10.1177/1087054715584055. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Browne M. Orthogonal rotation to a partially specified target. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 1972;25:115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Canals, J., Morales-Hidalgo, P., Jané, M.C., & Domènech, E. (2016). ADHD Prevalence in Spanish preschoolers: Comorbidity, socio-demographic factors, and functional consequences. Journal of Attention Disorders. doi: 10.1177/1087054716638511. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Català-López F., Peiró S., Ridao M., Sanfélix-Gimeno G., Gènova-Maleras R., Catalá M. Prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among children and adolescents in Spain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:168–181. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners C.K. Multi-Health Systems; Toronto, Ontario: 1989. Conners's Rating Scales. [Google Scholar]

- Conners C.K. Multi-Health Systems; Toronto, Ontario: 1997. Conners's Rating Scales Revised. [Google Scholar]

- Conners C.K. 3rd Edition. Multi-Health Systems; Toronto, Ontario: 2008. Conners. [Google Scholar]

- Conners C.K. Multi-Health Systems; Toronto, Ontario: 2009. Conners Early Childhood. [Google Scholar]

- De la Osa N., Granero R., Trepat E., Domenech J.M., Ezpeleta L. The discriminative capacity of CBCL/1½-5-DSM5 scales to identify disruptive and internalizing disorders in preschool children. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2016;25(1):17–23. doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0694-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul G.J., Anastopoulos A.D., Power T.J., Reid R., Ikeda M.J., McGoey K.E. Parent ratings of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms: Factor structure and normative data. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavavioral Assessment. 1998;20:83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ezpeleta L., De la Osa N., Domènech J.M. Prevalence of DSM-IV disorders, comorbidity and impairment in 3-year-old Spanish preschoolers. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2014;49:145–155. doi: 10.1007/s00127-013-0683-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farre-Riba A., Narbona J. Conners’ rating scales in the assessment of attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity (ADHD). A new validation and factor analysis in Spanish children. Revista de Neurología. 1997;25:200–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrando, P.J. & Lorenzo-Seva, U. (2013). Unrestricted item factor analysis and some relations with item response theory. Technical Report. Department of Psychology, Universitat Rovira i Virgili.

- González-Castro P., Rodríguez C., Cueli M., García T., Álvarez D. Diferencias en ansiedad estado-rasgo y en atención selectiva en Trastorno por Déficit de Atención con Hiperactividad (TDAH) International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2015;15(2):105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grupo de Trabajo de la Guía de Práctica Clínica, GPC (2010). Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre el Trastorno por Déficit de Atención con Hiperactividad (TDAH) en Niños y Adolescentes. Plan de Calidad para el Sistema Nacional de Salud del Ministerio de Sanidad, Política Social e Igualdad. Agència d’Informació, Avaluació i Qualitat de Cataluña; 2010. Guías de Práctica Clínica en el SNS: AATRM N° 2007/18.

- Gudmundsson O.O., Magnusson P., Saemundsen E., Lauth B., Baldursson G., Skarphedinsson G., Fombonne E. Psychiatric disorders in an urban sample of preschool children. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2013;18:210–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2012.00675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J., Birmaher B., Brent D., Rao U., Flynn C., Moreci P., Williamson D., Ryan N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Seva U., Ferrando P.J. FACTOR 9.2 A Comprehensive Program for Fitting Exploratory and Semiconfirmatory Factor Analysis and IRT Models. Applied Psychological Measurement. 2013;37:497–498. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Seva U., ten Berge J.M.F. Tucker's Congruence Coefficient as a Meaningful Index of Factor Similarity. Methodology. 2006;2:57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-García I., Delgado-Pardo G., de Rey C.C.V., Meneres-Sancho S., Servera-Barceló M. Neurofeedback, tratamiento farmacológico y terapia de conducta en hiperactividad: análisis multinivel de los efectos terapéuticos en electroencefalografía. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2015;15:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero I., León O.G. Guía para nombrar los estudios de investigación en Psicología. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2007;7:847–862. [Google Scholar]

- Narad M.E., Garner A.A., Peugh J.L., Tamm L., Antonini T.N., Kingery K.M., Simon J., Epstein J.N. Parent–teacher agreement on ADHD symptoms across development. Psychological Assessment. 2015;27:239. doi: 10.1037/a0037864. doi: 10.1037/a0037864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, NICE . The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrist; London: 2016. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Diagnosis and management (CG72) [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill S., Schneiderman R.L., Rajendran K., Marks D.J., Halperin J.M. Reliable ratings or reading tea leaves: Can parent, teacher, and clinician behavioural ratings of pre-schoolers predict ADHD at age six? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42:623–634. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9802-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaioannou S., Mouzaki A., Sideridis G.D., Antoniou F., Padeliadu S., Simos P.G. Cognitive and academic abilities associated with symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A comparison between subtypes in a Greek non-clinical sample. Educational Psychology. 2016;36:138–158. [Google Scholar]

- Sardinero E., Pedreira J.L., Muñiz J. El cuestionario CBCL de Achenbach: adaptación española y aplicaciones clínico-epidemiológicas. Clínica y Salud. 1997;8:447–480. [Google Scholar]

- Scholtens S., Rydell A.M., Yang-Wallentin F. ADHD symptoms, academic achievement, self-perception of academic competence and future orientation: A longitudinal study. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2013;54:205–212. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson J.M., Kraemer H.C., Hinshaw S.P., Arnold L.E., Conners C.K., Abikoff H.B., Clevenger W., Davies M., Elliot G.R., Greenhill L.L., Hechtman L., Hoza B., Jensen P.S., March J.S., Newcorn J.H., Owens E.B., Pelham W.E., Schiller E., Severe J.B., Simpson S., Vitiello B., Wells K., Wigal T., Wu M. Clinical relevance of the primary findings of the MTA: Success rates based on severity of ADHD and ODD symptoms at the end of treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:168–179. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200102000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmerman M.E., Lorenzo-Seva U. Dimensionality Assessment of Ordered Polytomus Items with Parallel Analysis. Psychological Methods. 2011;16:209–220. doi: 10.1037/a0023353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R., Sanders S., Doust J., Beller E., Glasziou P. Prevalence of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e994–e1001. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulloa R.E., Ortiz S., Higuera F., Nogales I., Fresán A., Apiquian R., Cortés J., Arechavaleta B., Foulliux C., Martínez P., Hernández L., Domínguez E., De la Peña F. Inter-rater reliability of the Spanish Version of Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Life time Version (K-SADS-PL) Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría. 2006;34:36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichstrøm L., Berg-Nielsen T.S., Angold A., Link Egger H., Solheim E., Sveen T.H. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in preschoolers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2013;53:695–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, WHO . WHO; Geneva: 1992. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders. [Google Scholar]