Abstract

Separase halves eukaryotic chromosomes in M‐phase by cleaving cohesin complexes holding sister chromatids together. Whether this essential protease functions also in interphase and/or impacts carcinogenesis remains largely unknown. Here, we show that mammalian separase is recruited to DNA double‐strand breaks (DSBs) where it is activated to locally cleave cohesin and facilitate homology‐directed repair (HDR). Inactivating phosphorylation of its NES, arginine methylation of its RG‐repeats, and sumoylation redirect separase from the cytosol to DSBs. In vitro assays suggest that DNA damage response‐relevant ATM, PRMT1, and Mms21 represent the corresponding kinase, methyltransferase, and SUMO ligase, respectively. SEPARASE heterozygosity not only debilitates HDR but also predisposes primary embryonic fibroblasts to neoplasia and mice to chemically induced skin cancer. Thus, tethering of separase to DSBs and confined cohesin cleavage promote DSB repair in G2 cells. Importantly, this conserved interphase function of separase protects mammalian cells from oncogenic transformation.

Keywords: cohesin, DNA double‐strand breaks, homology‐directed repair, posttranslational modifications, separase

Subject Categories: Cell Cycle; DNA Replication, Repair & Recombination; Post-translational Modifications, Proteolysis & Proteomics

Introduction

DNA double‐strand breaks (DSBs) pose an enormous threat to genome integrity because they frequently lead to cancer‐associated translocations. Therefore, DSBs trigger a DNA damage response (DDR) leading to checkpoint‐mediated cell cycle arrest followed by DSB repair or apoptosis (Polo & Jackson, 2011). DDR involves hierarchical recruitment and diverse posttranslational modifications (PTMs) of proteins at DSBs. Early steps are phosphorylation of histone variant H2AX at Ser139 (resulting in γH2AX) and Arg‐methylation‐dependent recognition and resection of DSBs by the MRE11‐RAD50‐NBS1 (MRN) complex (Polo & Jackson, 2011; Thandapani et al, 2013). One branch of the subsequent DNA damage signaling cascade consists of MRN‐mediated recruitment and activation of ATM kinase which—together with MDC1, 53BP1, and other mediators—phosphorylates the effector kinase Chk2 (Polo & Jackson, 2011). Non‐homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homology‐directed repair (HDR) represent the two major pathways of downstream DSB repair. The error‐free HDR occurs primarily in S‐ and G2‐phase cells because it usually requires the undamaged sister chromatid as a homologous template (Polo & Jackson, 2011).

The cohesin complex, whose Smc1, Smc3, and Rad21/Scc1 subunits form a 40‐nm tripartite ring, also plays an important role in DSB repair (Sjogren & Nasmyth, 2001). However, its canonical functions lie in sister chromatid cohesion and chromosome separation (Nasmyth & Haering, 2009). Loading of cohesin onto chromatin in telophase (higher eukaryotic cells) or late G1 (yeast) is catalyzed by an Scc2‐Scc4 complex, known as kollerin, and may involve transient detachment of Smc1 from Smc3 (Nasmyth & Haering, 2009). Concomitant to replication in S‐phase, the two arising sister chromatids of each chromosome are then entrapped within cohesin rings and, thus, paired. Cohesion is stabilized by Esco1/2‐dependent acetylation of Smc3 and binding of sororin and counteracted by the anti‐cohesive factor Wapl (Nasmyth & Haering, 2009). Phosphorylation‐dependent inactivation of sororin in early mitosis enables Wapl to somehow open the Smc3‐Rad21 gate, thereby displacing cohesin from chromosome arms (Buheitel & Stemmann, 2013; Nishiyama et al, 2013). Centromeric cohesin/sororin is stabilized by Sgo1‐PP2A‐dependent dephosphorylation and removed only at the metaphase‐to‐anaphase transition when degradation of securin liberates separase to proteolytically cleave Rad21 (Uhlmann et al, 2000; Liu et al, 2013). Interestingly, a single DSB in yeast triggers the replication‐independent, genome‐wide enforcement of sister chromatid cohesion by de novo loading of cohesin. This recruitment was most profound at the break and occurred in a γH2AX‐, MRE11‐, and kollerin‐dependent manner (Strom et al, 2004, 2007; Unal et al, 2004, 2007). On the other hand, Aragón et al reported a decrease in cohesin from DSBs when re‐synthesis of Rad21 was inhibited (McAleenan et al, 2013). This decrease coincided with the damage‐induced formation of Rad21 fragments and the impairment of DSB repair by expression of a separase‐resistant Rad21 variant, observations which had previously been reported also for Schizosaccharomyces pombe and which suggested activation of separase during DDR in postreplicative yeast cells (Nagao et al, 2004; McAleenan et al, 2013). Cohesin accumulates at DSBs also in human cells (Kim et al, 2002; Potts et al, 2006). However, whether mammalian separase is activated during DDR to cleave cohesin at DSBs remains an unresolved issue.

Overexpression of separase results in aneuploidy and tumorigenesis in the mouse model, occurs in several human cancers, and is associated with poor clinical outcome (Zhang et al, 2008; Meyer et al, 2009; Finetti et al, 2014; Mukherjee et al, 2014a,b). Conversely, SEPARASE heterozygosity also causes genomic instability and cancer in zebrafish and p53 null mice (Shepard et al, 2007; Mukherjee et al, 2011) arguing that SEPARASE is both an oncogene and a tumor suppressor gene at the same time and that separase's proteolytic activity needs tight control. Whether separase's role in tumorigenesis is due to its role in sister chromatid segregation and/or a hitherto unknown function still needs clarification.

Here, we show that separase associates with DSBs in postreplicative cells, where it is activated to locally cleave cohesin and facilitate HDR. Its recruitment to damaged DNA requires three PTMs of separase: inhibitory phosphorylation of a nuclear export sequence (NES), Arg‐methylation of a conserved RG‐repeat motif, and sumoylation of Lys1034. Importantly, SEPARASE heterozygosity simultaneously results the reduced DDR and heightened predisposition to oncogenic transformation.

Results

Separase is recruited to DSBs

Previous yeast studies implied a role of separase in DDR (Nagao et al, 2004; McAleenan et al, 2013). To address whether human separase might have a similar function, we adopted a system to induce site‐specific DSBs (Iacovoni et al, 2010; Caron et al, 2012). Upon addition of 4‐hydroxytamoxifen (OHT), the restriction endonuclease AsiSI fused to an estrogen receptor (ER) re‐locates from the cytosol into the nucleus to cleave DNA at 8‐bp recognition sites (around 200 per cell; Chailleux et al, 2014), thereby triggering formation of γH2AX‐ and phosphoChk2‐positive foci (Fig EV1A). When ER‐AsiSI was expressed in a transgenic HEK293 line that inducibly produces Myc‐tagged separase in response to doxycycline (Dox) addition (Boos et al, 2008), separase formed nuclear foci that co‐localized with γH2AX—but only when both OHT and Dox were present (Fig EV1B). Similarly, overexpressed separase localized to γH2AX‐positive foci when the topoisomerase II inhibitor doxorubicin (DRB) was used to inflict DSBs (Fig EV1C). Importantly, endogenous separase also co‐localized with γH2AX to sites of DNA damage as judged by immunofluorescence microscopy (IFM) of DRB‐treated HEK293 cells. Demonstrating the specificity of the DRB‐induced separase foci, they were absent in separase‐depleted and undamaged cells (Figs 1A and EV1D). To independently confirm recruitment of endogenous separase to damaged sites, we conducted chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments followed by multiplex qPCR or qPCR (see Fig EV1E for length and positions of PCR products). These analyses consistently revealed that, much like an anti‐γH2AX and unlike non‐specific IgG, a separase antibody precipitated DNA close to two different AsiSI sites if and only if OHT was added, while a region that was more than 2.2 Mbp away from the nearest AsiSI site did not co‐purify (Fig 1B and C). The specific recruitment of separase to DSBs was further enhanced by induced overexpression of the protease (Fig EV1F).

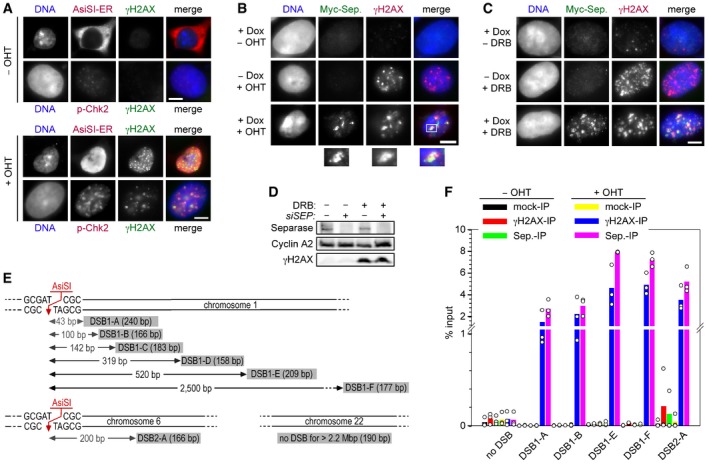

Figure EV1. Separase localizes to DSBs.

- A system for induced introduction of site‐specific DSBs. Transgenic HEK293 cells constitutively expressing FLAG‐tagged AsiSI‐ER were treated with OHT or carrier solvent and then analyzed by IFM as indicated. Scale bar = 5 μm.

- Transgenic HEK293 cells treated with Dox to induce expression of Myc‐separase‐WT and/or with OHT to induce nuclear accumulation of ER‐AsiSI and DSBs were analyzed by IFM as indicated. Scale bar = 5 μm.

- γH2AX‐ and separase‐positive foci formation in response to DNA damage by DRB. Prior to their analysis by IFM, transgenic HEK293 cells in G2‐phase were Dox‐ and/or DRB‐treated to induce the expression of Myc‐separase and/or inflict DSBs, respectively. Scale bar = 5 μm.

- Western blot analysis of experiment shown in Fig 1A.

- Position and sizes of PCR fragments from the ChIP–multiplex PCR and ChIP‐qPCR experiments. Schematic is not drawn to scale.

- Transgenic HEK293 cells supplemented with Dox to induce expression of Myc‐separase‐WT were mock‐ or OHT‐treated in G2‐phase and then subjected to ChIP‐qPCR. Shown are averages (bars) of three independent experiments (dots).

Figure 1. Human separase localizes to DSBs in postreplicative cells.

-

AFollowing transfection of given siRNAs and synchronization in G2‐phase, Hek293 cells were DRB‐ or mock‐treated and then subjected to IFM using the indicated antibodies. Lower panels display a threefold magnification of the boxed area shown above. Scales bars correspond to 5 and 1 μm, respectively. See Fig EV1D for corresponding immunoblot.

-

BHEK293 cells were thymidine‐arrested for 20 h, mock‐ or OHT‐treated to induce DSBs by nuclear accumulation of ER‐AsiSI, and then subjected to ChIP–multiplex PCR.

-

CChIP samples from (B) were analyzed by qPCR. Shown are averages (bars) of three independent experiments (dots).

-

D, ESeparase interacts with γH2AX in DSB‐containing G2 but not G1 cells. Transgenic HEK293 cells treated with Dox to induce expression of Myc‐separase‐WT and with OHT to induce nuclear accumulation of ER‐AsiSI and infliction of DSBs were synchronized in G1‐ or G2‐phase and analyzed by IP–Western blotting (D) and by IFM for γH2AX‐ and Myc‐separase‐positive foci (see Fig EV2E). The quantification of the IFM in (E) shows averages (bars) of three independent experiments (dots) counting ≥ 100 cells each.

Separase functions in HDR but not NHEJ

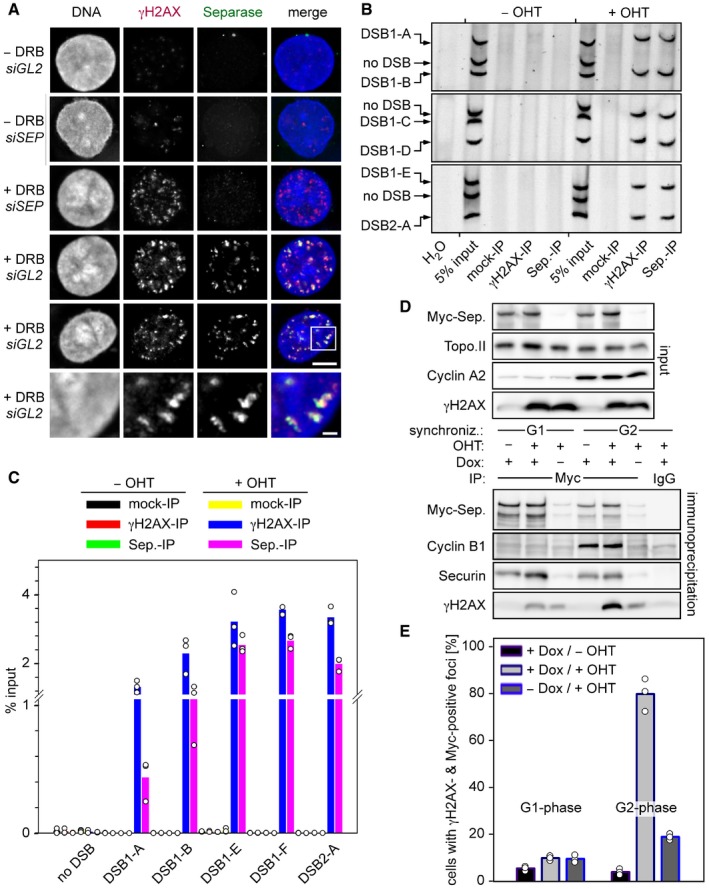

Is separase of functional importance for DNA damage repair? Indicating that this might indeed be the case, depletion of separase but not mock treatment strongly compromised the ability of HEK293 cells to form colonies in the presence of camptothecin, a topoisomerase I inhibitor that causes replication‐dependent DNA single‐ and double‐strand breaks (Fig EV2A and B).

Figure EV2. Depletion of Separase by RNAi compromises HDR as judged by a GFP‐based in vivo assay.

-

A, BDepletion of separase renders human cells hypersensitive to camptothecin. Twelve hours after transfection of the indicated siRNAs, 100 HEK293 cells each were plated onto 10‐cm petri dishes. Another 12 h later, camptothecin (0.25 nM end concentration) or carrier solvent (DMSO) was added. Colonies were stained by crystal violet 12 days thereafter and photographed (A). For each condition, three independent experiments were quantified by ImageJ (dots) and averaged (bars) (B).

- C

-

DDox‐ and OHT‐treated HEK293 cells synchronized in G1‐ or G2‐phase were propidium iodide (PI)‐stained and analyzed by DNA content by flow cytometry.

-

ERepresentative IFM images of Dox‐ and OHT‐treated HEK293 cells synchronized in G1‐ or G2‐phase. Scale bar = 5 μm.

-

F, GU2OS DR‐GFP (HDR reporter) cells were transfected with GL2 or one of five different SEPARASE‐directed siRNAs. Following a second transfection to express ER‐tagged I‐SceI and addition of OHT to induce nuclear accumulation of the homing endonuclease, cells were subjected to flow cytometry (G) and immunoblotting (F).

We noted that not all γH2AX‐positive interphase cells showed Myc‐separase foci and therefore pre‐synchronized ER‐AsiSI‐expressing cells in either G1‐ or G2‐phase prior to OHT addition and analyses (see Fig EV2C for timeline of the experiment). Successful synchronization was confirmed by measurement of cyclin A2 and DNA contents by immunoblotting and flow cytometry, respectively (Figs 1D and EV2D). Lysates from these different cell populations were benzonase‐treated to digest DNA and then subjected to IP using anti‐Myc or unspecific IgG. Interestingly, γH2AX specifically co‐purified with Myc‐separase from OHT‐treated G2‐ but not G1‐phase cells (Fig 1D, lower part). Consistently, IFM revealed that 80% of DSBs containing G2 cells exhibited γH2AX‐ and Myc‐separase‐positive foci as compared to merely 10% in the G1‐enriched pool (Figs 1E and EV2E). Due to imperfect synchronization of the HEK293 cells (Fig EV2D), this probably represents an underestimation. These data therefore imply that separase is recruited to DSBs exclusively in postreplicative cells.

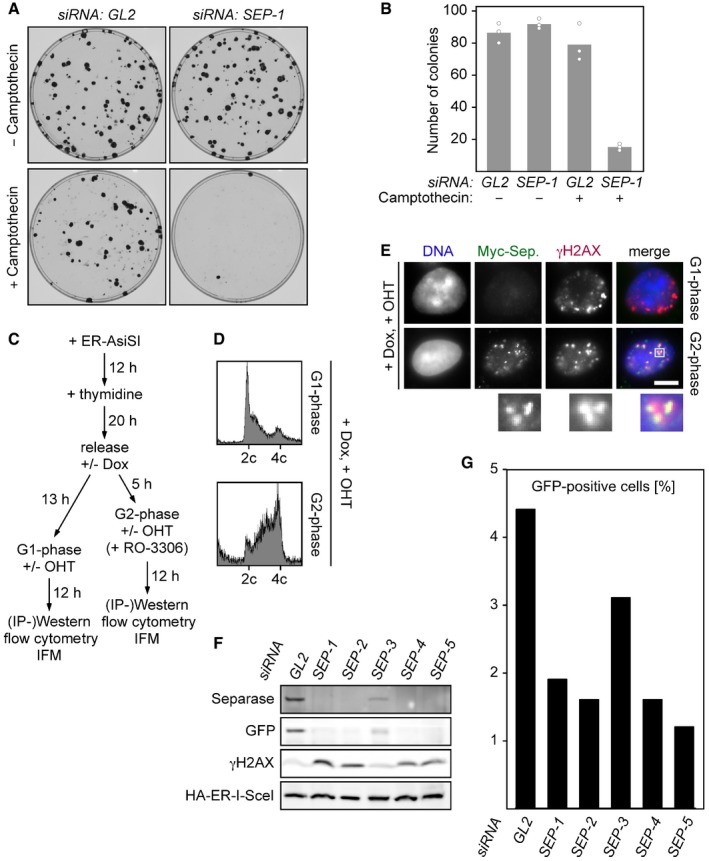

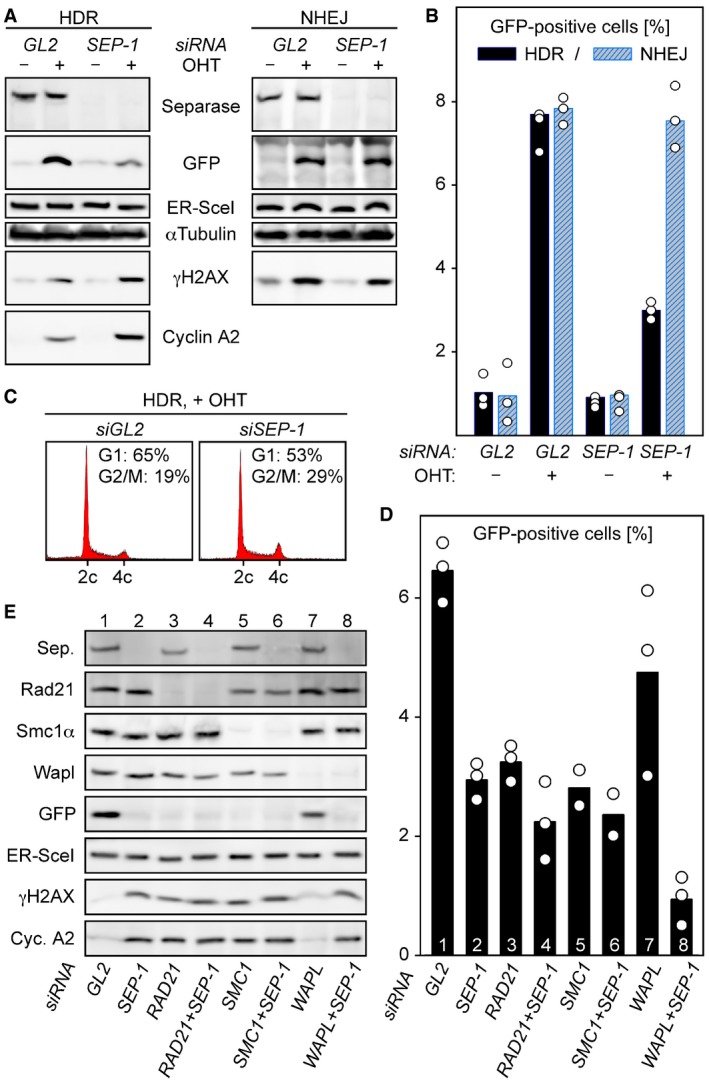

Because HDR, but not NHEJ, requires the undamaged sister chromatid as a homologous template, the above result indicates a possible role of separase in HDR rather than NHEJ. To resolve this issue, we adopted in vivo assays for HDR versus NHEJ (Pierce et al, 1999; Gunn & Stark, 2012). Herein, the homing endonuclease I‐SceI in corresponding transgenic U2OS cells introduces a single DSB, the repair of which creates a functional GFP expression cassette only if it occurs by HDR in one reporter line and by NHEJ in the other. Following transfection of a SEPARASE‐directed (SEP‐1) or control siRNA (GL2), the corresponding cells were again transfected to express I‐SceI in fusion with an estrogen receptor (ER) and synchronized in early S‐phase. Six hours after release from thymidine arrest, cells were supplemented with OHT to induce nuclear accumulation of the homing endonuclease (or with carrier solvent as a negative control). Two days thereafter, cells were harvested and analyzed for protein content by immunoblotting and for GFP fluorescence and DNA content by flow cytometry. The OHT‐induced GFP expression was unaffected by separase in the NHEJ reporter line (Fig 2A and B). However, in the HDR reporter line depletion of separase resulted in a markedly reduced GFP Western signal (Fig 2A) and 2.6‐fold less GFP‐positive cells (Fig 2B). At the time of analysis, OHT‐treated HDR reporter cells lacking separase also displayed slightly enhanced γH2AX and cyclin A2 signals and a modest accumulation in G2/M (Fig 2A and C; see also Fig EV2F). This is consistent with a compromised repair proficiency and consequent DNA damage checkpoint‐dependent delay of mitotic entry. To exclude the possibility that compromised HDR in separase‐depleted reporter cells was due to an off‐target effect, we tested four additional SEPARASE‐directed siRNAs (SEP‐2‐5) in the same assay. All reduced the number of GFP‐positive cells relative to the GL2 control, and all but one (SEP‐3) did so to a similar extent as did SEP‐1 (Fig EV2F and G). Consistent with SEPARASE being the relevant target, the weaker effect of SEP‐3 correlated with its weaker knock‐down efficiency (Fig EV2F). In summary, these results demonstrate that human separase is required for proper HDR but dispensable for NHEJ.

Figure 2. Separase supports HDR but not NHEJ .

-

A–CSeparase is required for proper HDR but dispensable for NHEJ. U2OS DR‐GFP (HDR reporter) and U2OS EJ5‐GFP (NHEJ reporter) cells were separase‐depleted by RNAi (SEP‐1) or control‐treated with GL2 siRNA, transfected to express HA‐tagged ER‐I‐SceI, and then supplemented with OHT in G2‐phase to induce nuclear accumulation of the homing endonuclease. Ethanol‐supplemented samples served as negative controls. Two days later, cells were subjected to immunoblotting (A) and flow cytometry to quantify the percentage of GFP‐positive cells (B) and PI‐stained cellular DNA (C). The GFP quantification in (B) displays averages (bars) of three independent experiments (dots).

-

D, ECo‐depletion of Wapl and separase has a synergistic effect on HDR. U2OS DR‐GFP cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs, treated as in (A + B) and analyzed by GFP flow cytometry (D) and immunoblotting (E). Shown in (D) are averages (bars) of two to three independent experiments (dots).

A role of cohesin in HDR is well established (Kim et al, 2002; Strom et al, 2004; Unal et al, 2004; Potts et al, 2006). Simultaneous requirement of its antagonist separase in the same repair pathway seems counterintuitive at first. To clarify this issue, we analyzed side by side the effects of cohesin and separase single and double depletions in the abovementioned GFP‐based HDR assay. Flow cytometric quantification showed that RNAi of separase, Rad21, or another cohesin subunit, Smc1α, all reduced the amount of GFP‐positive cells to a similar extent and at least by a factor of 2, thereby confirming the requirement of both cohesin and separase for proper HDR (Fig 2D, columns 1–3 and 5). Interestingly, simultaneous knock‐down of separase together with Rad21 or Smc1α only marginally aggravated the HDR defect relative to the single depletions (compare columns 2–6). We believe that effective HDR requires heightening of both density and turnover of cohesin at DSBs (see Discussion). Co‐depletion of separase will increase residual cohesion under conditions when cohesin becomes limiting, and this might compensate for the negative effect on HDR of reduced cohesin dynamics due to the sole absence of separase.

We also investigated Wapl, another anti‐cohesive factor with key function in proteolysis‐independent cohesin removal (Kueng et al, 2006). While Wapl depletion alone reduced the GFP formation only mildly, simultaneous knock‐down of Wapl and separase had a clear synergistic effect reducing the amount of GFP‐positive cells in the individual depletions from 2.8 and 4.6%, respectively, to 1% in the double knock‐down (Fig 2D, columns 2, 7, and 8). This suggests that total abrogation of cohesin dynamics by interference with both known anti‐cohesive mechanisms leads to maximal impairment of HDR. Immunoblotting not only confirmed the successful and even knock‐downs but also the flow cytometric quantification of GFP (Fig 2E). Moreover, it revealed increased levels of γH2AX and cyclin A2 in the absence of cohesin and/or separase indicating DSB persistence and checkpoint‐mediated cell cycle arrest under these conditions (lower two panels).

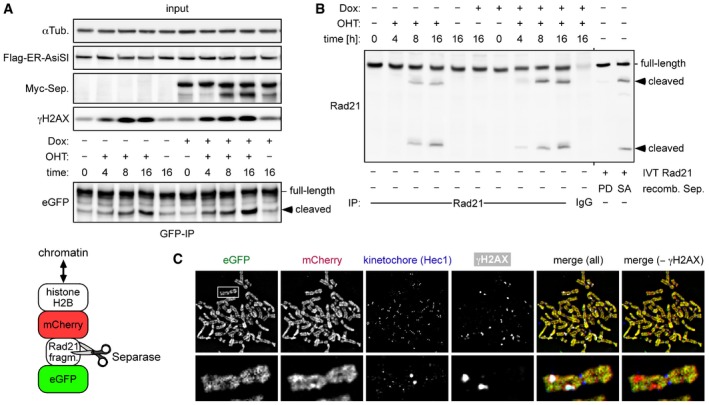

Separase is activated at DSBs where it locally cleaves cohesin

Does human separase get activated to cleave cohesin in response to DSBs similar to the situation in yeast? To address this question, histone H2B‐mCherry‐Rad21107–268‐eGFP was constitutively expressed in MYC‐SEPARASE cells (Fig 3A, cartoon at bottom). Separase‐dependent cleavage of this protease activity sensor causes mCherry‐ and eGFP‐positive chromatin to selectively lose its eGFP signal. These doubly transgenic cells were transfected to transiently express also AsiSI‐ER, treated with OHT or carrier solvent for different times, and analyzed by immunoblotting (Fig 3A and B). Indeed, this demonstrated DNA damage‐dependent proteolysis of the sensor (Fig 3A, bottom panel). Enrichment by IP of its soluble cleavage products revealed that endogenous Rad21 is also cleaved and that these cleavage events increased with duration of DSB induction, i.e., OHT treatment (Fig 3B). Separase activity was only slightly enhanced by Dox‐induced overexpression (Fig 3A and B), although this resulted in considerably more protease being recruited to sites of DNA damage as revealed by ChIP‐qPCR (compare Figs 1C and EV1F). Under these conditions, the activation of separase therefore seems to be limiting.

Figure 3. Human separase locally cleaves Rad21 at DSBs.

- Transgenic HEK293 cells constitutively expressing a separase sensor (cartoon below) and inducibly expressing Myc‐separase were transiently transfected to express Flag‐AsiSI‐ER, Dox‐ and/or OHT‐treated in G2‐phase, and analyzed by IP–Western blotting.

- Cells from (A) were analyzed by IP–Western blotting for cleavage of endogenous Rad21. As a control, in vitro‐translated (IVT) Rad21 was incubated with hyperactive separase‐SA or a protease‐dead (PD) variant (Boos et al, 2008).

- Sensor‐expressing cells were treated in G2‐phase with DRB and nocodazole for 6 and 2 h, respectively, prior to chromosome spreading and IFM using Hec1 and γH2AX antibodies. The separase sensor was detected based on autofluorescence of eGFP and mCherry, while Hec1 and γH2AX antibodies were detected with corresponding Cy5‐ and marina blue‐labeled secondary antibodies, respectively. Note that sizes of spread chromosomes vary greatly with buffer conditions, which is why no scale bar is shown.

When sensor‐expressing cells were treated in G2‐phase with DRB and the spindle toxin nocodazole, subsequent chromatin spreads displayed some mitotic figures with γH2AX‐positive foci on condensed chromosomes, suggesting that the corresponding cells had slipped from the DNA damage into the mitotic checkpoint arrest (Fig 3C). Notably, γH2AX foci coincided with regions of decreased eGFP fluorescence (or relative increase in mCherry over eGFP in an overlay) indicative of local separase‐dependent sensor cleavage. This net loss of sensor from DSBs does not contradict the reported overall accumulation of cohesin at DSBs because loading mechanisms are fundamentally different for authentic cohesin versus the histone‐based sensor. Together, these results strongly indicate that separase is activated at sites of DSBs to locally cleave cohesin during DDR.

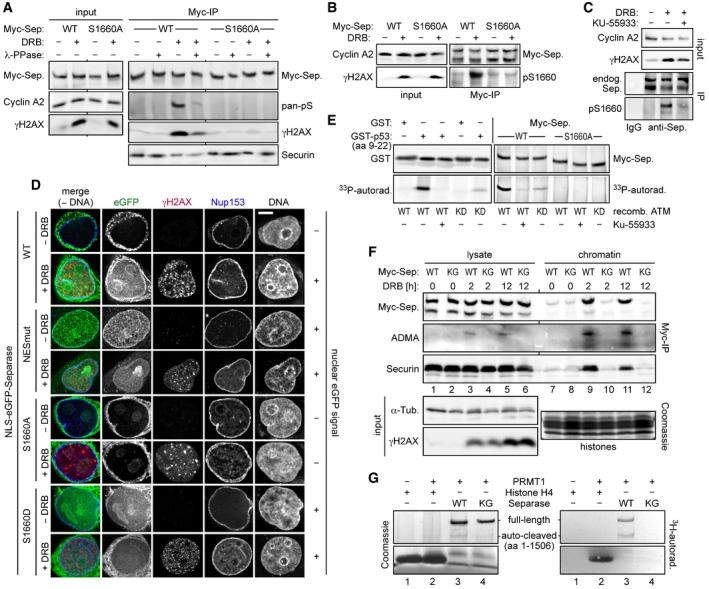

DNA damage‐ and phosphorylation‐dependent inactivation of separase's NES

In undamaged interphase cells, separase is excluded from the nucleus due to the presence of a nuclear export sequence (NES) centered around position 1665 (Sun et al, 2006). Therefore, its NES might be inactivated in response to DSBs to retain separase in the nucleus. Interestingly, an NES in p53 is inhibited by DNA damage‐induced phosphorylation (Zhang & Xiong, 2001) and separase's NES is immediately flanked by a serine at position 1660. When Myc‐separase‐WT was immunoprecipitated from cyclin A2‐positive, DRB‐treated G2‐phase cells, separase was detected in an immunoblot by a pan‐specific phosphoSer antibody (Fig 4A). This signal was greatly diminished in the absence of DNA damage or when samples were phosphatase‐treated prior to SDS–PAGE. Importantly, the phosphoSer signal was also missing when a Ser‐1660 to Ala variant instead of separase‐WT was immunoprecipitated from DRB‐treated G2 cells. At the same time, γH2AX co‐purified with separase‐WT but not separase‐S1660A from benzonase‐treated cell lysates (Fig 4A), suggesting that the phosphorylation site variant is unable to associate with DSBs (see below).

Figure 4. NES phosphorylation and RG‐repeat methylation of separase in response to DSBs.

-

A–CSer1660 is phosphorylated in response to DNA damage and required for the interaction of separase with γH2AX. HEK293 cells were arrested in G2‐phase by sequential thymidine and RO‐3306 treatment, DRB‐ (+) or mock‐treated (−), and then analyzed as indicated. (A and B) Myc‐separase‐WT or Myc‐separase‐S1660A‐expressing cells were subjected to IP–Western blotting using, among others, a pan‐specific antibody against phosphorylated serine (A, pan‐pS) or a separase antibody specific for phosphorylated Ser1660 (B, pS1660). (C) DNA damage‐induced Ser1660 phosphorylation of endogenous separase is largely blocked by ATM inhibition. G2‐enriched HEK293 cells were treated with KU‐55933 (0.3 μM) and/or DRB and analyzed by IP–Western blotting 12 h thereafter using the indicated antibodies.

-

DPreventing NES phosphorylation spoils nuclear localization of separase in response to DSBs. HeLaK cells expressing N‐terminally NLS‐eGFP‐tagged separase variants were treated with DRB or carrier solvent (− DRB) for 4 h and then subjected to IFM using anti‐γH2AX and anti‐Nup153 to visualize sites of DNA damage and nuclear pore complexes, respectively. Transgenic separase was detected based on the eGFP autofluorescence. Note that due to their relatively high nuclear concentration, co‐localization of separase‐WT and separase‐S1660D with γH2AX foci is not discernable. Scale bar = 5 μm.

-

EIn vitro phosphorylation of separase on Ser1660 by ATM kinase. Incubation of GST‐p53 (amino acids 9–22), GST, separase‐WT, or separase‐S1660A with recombinant ATM‐WT, ATM‐KD (kinase dead), and/or KU‐55933 in the presence of [γ‐33P]‐ATP was followed by immunoblotting and autoradiography.

-

FArg‐methylation of RG‐repeats mediates recruitment of separase to DSB‐containing chromatin. Myc‐separase‐WT‐ or Myc‐separase‐KG‐expressing cells were treated with DRB as indicated and analyzed by IP–Western blotting and Coomassie staining.

-

GIn vitro Arg‐methylation of separase's RG‐repeats by PRMT1. Incubation of histone H4, separase‐WT, or separase‐KG with recombinant PRMT1 or reference buffer in the presence of S‐adenosyl‐L‐[methyl‐3H]‐methionine was followed by Coomassie staining and autoradiography.

We then raised an antibody that specifically recognized phosphorylated Ser‐1660 of separase. Confirming our earlier interpretations, this anti‐pS1660 strongly reacted with full‐length Myc‐separase‐WT from DSB‐containing cells (Fig 4B). In contrast, Myc‐separase‐S1660A from accordingly DRB‐treated cells and separase‐WT from undamaged G2‐arrested control cells were hardly recognized. Importantly, this tool also allowed us to detect the NES phosphorylation of endogenous separase upon infliction of DSBs in untransfected, G2‐arrested HEK293T cells (Fig 4C).

Visible nuclear accumulation of separase (in the absence of DNA damage) requires both mutational inactivation of the NES and fusion of the protease with a nuclear localization sequence (NLS; Sun et al, 2006). Transiently expressed NLS‐eGFP‐separase accumulated in nuclei not only when bulky hydrophobic residues within the NES were replaced by alanines (NESmut) but also when DSBs were inflicted instead (Fig 4D, 2nd and 3rd panel from top). In contrast, NLS‐eGFP‐separase‐S1660A was absent from nuclei even in DRB‐treated cells (6th panel from top). Interestingly, an NLS‐eGFP‐separase variant, in which Ser‐1660 was changed to phosphorylation‐mimetic Asp, behaved similar to separase‐NESmut in that it exhibited nucleoplasmic localization even in the absence of DNA damage (7th panel from top). Collectively, these results suggest that DNA damage‐induced phosphorylation of separase at Ser‐1660 inactivates its NES, thereby facilitating retention of the protease within the nucleoplasm, from where it can then be recruited to DSBs.

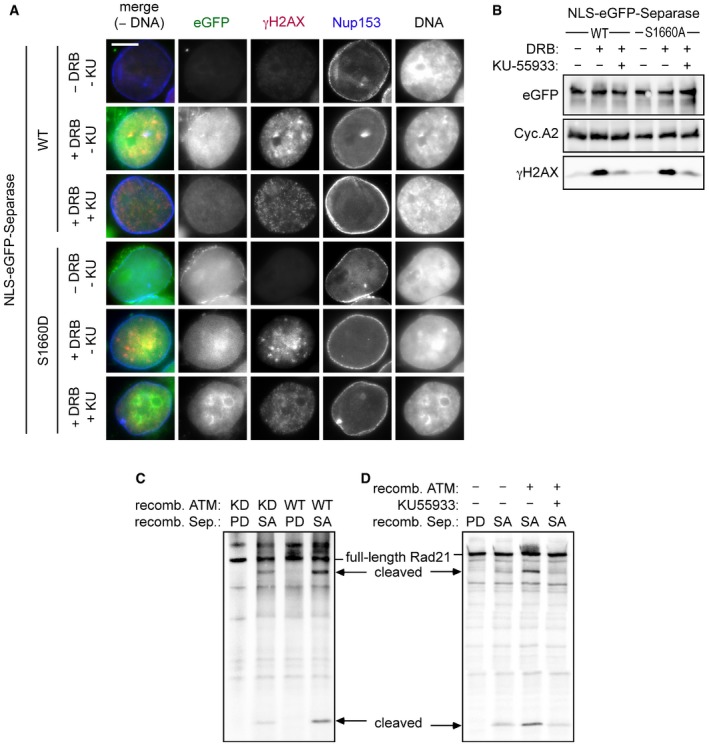

Ser‐1660 could serve as a substrate for ATM kinase according to a Scansite search, albeit at minimal stringency settings (Obenauer et al, 2003). Recombinant ATM purified from transiently transfected HEK293T cells phosphorylated p53's NES (amino acids 9–22) in fusion with GST, an established model substrate, but not GST alone (Fig 4E; Kim et al, 1999). Confirming its specificity, this signal was extinguished in the presence of the ATM‐specific inhibitor KU‐55933 and greatly diminished when a preparation of a kinase‐dead (KD) variant was used instead of ATM‐WT. Notably, the same results were observed using separase‐WT as a substrate, while separase‐S1660A was not phosphorylated at all. Thus, ATM is capable of phosphorylating separase's NES at Ser‐1660 in vitro. Consistent with these findings, KU‐55933 addition to DRB‐treated cells strongly reduced Ser‐1660 phosphorylation of separase (Fig 4C) and largely compromised the nuclear accumulation of NLS‐eGFP‐separase‐WT but not NLS‐eGFP‐separase‐S1660D (Fig EV3A and B). This is in line with separase's NES being a direct substrate of ATM in vivo although we cannot exclude indirect effects. Interestingly, active ATM also enhanced the cleavage of Rad21 by separase in vitro (Fig EV3C and D), which fits well to our aforementioned finding of local Rad21 cleavage at DSBs.

Figure EV3. ATM kinase activity is required for nuclear accumulation of separase in response to DSBs.

-

A, BHeLaK cells expressing N‐terminally NLS‐eGFP‐tagged separase‐WT or separase‐S1160D were treated with DRB, KU‐55933 (2 μM), or carrier solvent (−) for 4 h as indicated and then subjected to IFM and Western blot analysis using the indicated antibodies. Transgenic separase was detected based on the eGFP autofluorescence. Note that due to their relatively high nuclear concentration, co‐localization of separase‐WT and separase‐S1660D with γH2AX foci is not discernable. Scale bar = 5 μm.

-

C, DATM enhances separase‐dependent Rad21 cleavage in vitro. Rad21 was 35S‐labeled by in vitro expression in reticulocyte lysate and treated with recombinant ATM kinase in the presence of KU‐55933 (10 μM) and/or ATP. Then, samples were incubated with recombinant separase and finally analyzed by SDS–PAGE and autoradiography. Wild‐type (WT) or kinase‐dead (KD) variants of ATM and hyperactive (SA) or protease‐dead (PD) variants of separase were employed as indicated.

RG‐repeat methylation tethers separase to DSBs

Once retained in the nucleoplasm, how is separase recruited to DSBs? DNA damage response involves Arg‐methylation of several proteins within RGG‐ or RG‐repeat motifs (Thandapani et al, 2013). For example, the MRN complex component Mre11 can be modified by the protein arginine methyltransferase 1 (PRMT1), and this Arg‐methylation was demonstrated to be required for MRN's association with sites of DNA damage (Boisvert et al, 2005; Dery et al, 2008). Interestingly, vertebrate separases contain a short RG‐repeat motif. The RGRGRAR motif centered around position 1426 of the human enzyme was changed to KGKGKAK resulting in separase‐KG. Myc‐tagged versions of separase‐WT or separase‐KG were immunoprecipitated from DRB‐ or mock‐treated G2 cells. Subsequent immunoblotting revealed that separase‐WT from DSB‐containing cells was recognized by an asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA)‐specific antibody, while the KG variant was not (Fig 4F, lanes 3–6). Enrichment of chromatin prior to the IP demonstrated that separase's association with chromatin depended on both the DNA damage and an intact RG motif and yielded more intense ADMA signals (lanes 9–12). We established in vitro Arg‐methylation using bacterially expressed human PRMT1, S‐adenosyl‐L‐[methyl‐3H]‐methionine, and histone H4 as a model substrate (Fig 4G, lanes 1 and 2; Wang et al, 2001). Importantly, recombinant separase‐WT was readily methylated by PRMT1 in this assay, while the KG variant remained unmodified (lanes 3 and 4). In summary, these data suggest that Arg‐methylation of separase's RG motif, possibly by PRMT1, targets the protease to DSBs.

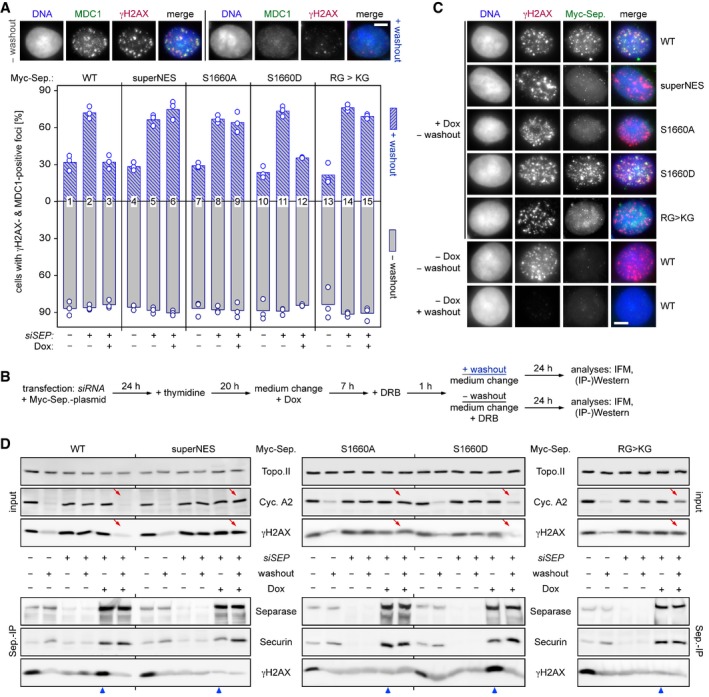

NES phosphorylation and RG‐repeat methylation are required for separase's function in DSB repair

While 87% of HEK293T cells cultivated in continued presence of DRB exhibited γH2AX‐ and MDC1‐positive foci, this fraction dropped to 32% within 24 h after DRB washout (Fig 5A, compare gray and blue bars in lane 1). Prior depletion of separase by RNAi resulted in persistence of damage foci in 72% of cells (blue bar, column 2), a defect which was fully reversed by Dox‐induced expression of Myc‐separase‐WT from an siRNA‐resistant transgene (column 3). This rescue offered the possibility to probe separase variants for their retained ability to support DSB repair (see Fig 5B for timeline of the experiment). Notably, separase‐S1660A and a variant, in which the NES was replaced by a non‐phosphorylatable superNES (Guttler et al, 2010), were unable to support DSB repair in this recovery assay, while the phospho‐mimicking separase‐S1660D did rescue (Fig 5A, compare columns 6, 9, and 12). γH2AX‐ and MDC1‐positive foci also persisted after DRB washout when endogenous separase was replaced by the KG variant (column 15). In contrast to separase‐WT and separase‐S1660D, all other variants failed to form damage‐induced foci and to interact with γH2AX in continued presence of DRB (Fig 5C and D, blue arrowheads). Moreover, separase‐WT and separase‐S1660D supported recovery from the DNA damage checkpoint‐induced G2 arrest as judged by drop in γH2AX and cyclin A2 levels, while separase‐superNES, separase‐S1660A, and separase‐KG again failed to do so (Fig 5D, red arrows). In summary, separase's ability to localize to DSBs correlates with DNA damage repair proficiency and depends on inhibitory phosphorylation of the NES and Arg‐methylation of the RG‐repeat motif.

Figure 5. NES phosphorylation and Arg‐methylation of separase are required for proper DSB repair.

- Persistence of γH2AX‐ and MDC1‐positive foci in the absence of NES phosphorylation or RG‐methylation of separase. Transfected HEK293T cells were siRNA‐ and Dox‐treated to deplete endogenous separase and induce expression of the indicated, siRNA‐resistant Myc‐tagged separase variants, respectively. Then, they were constitutively (− washout) or transiently exposed to DRB (+ washout) and finally quantitatively assessed by IFM for γH2AX‐ and MDC1‐positive foci. Shown are averages (bars) of three independent experiments (dots) counting ≥ 100 cells each. Scale bar = 5 μm.

- Schematic of the experiment.

- Recruitment of separase‐WT and separase‐S1660D but not separase‐superNES, separase‐S1660A, and separase‐KG to DSBs. Cells from (A) were treated as indicated and analyzed by IFM for co‐localization of Myc‐separase with γH2AX foci. Scale bar = 5 μm.

- Interaction of separase‐WT and separase‐S1660D but not separase‐superNES, separase‐S1660A, and separase‐KG with γH2AX. Cells from (A) were subjected to IP–Western blot analysis as indicated. Lanes that illustrate cellular levels of cyclin A2 and γH2AX after DRB washout and those that analyze interaction of Myc‐separase variants with γH2AX in the presence of DRB are labeled by red arrows and blue arrowheads, respectively.

Sumoylation of Lys1034 supports separase's role in DSB repair

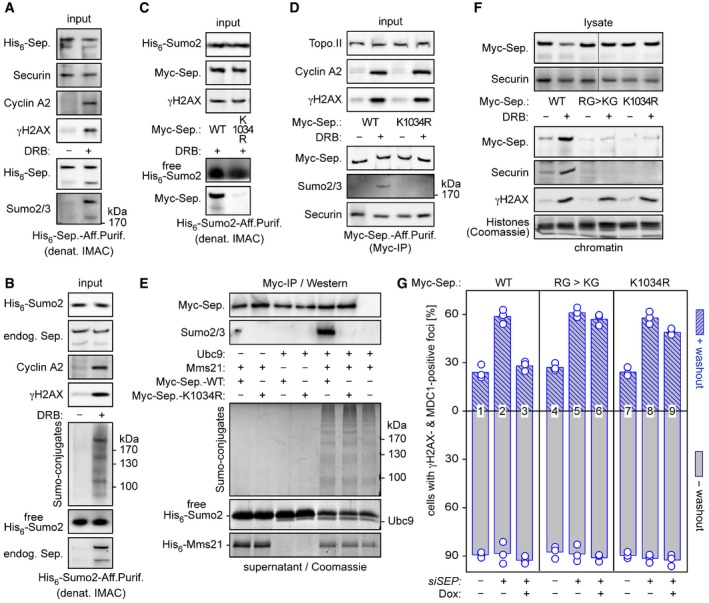

DNA double‐strand break recruitment of several proteins, among them 53BP1 and Rad52, is controlled by sumoylation (Sacher et al, 2006; Galanty et al, 2009). We therefore assessed whether separase might also be sumoylated during DDR. Cells that expressed His6‐separase were DRB‐ or control‐treated and subjected to denaturing immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography (IMAC). Subsequent comparative separase and Sumo2/3 immunoblotting revealed that separase is indeed sumoylated in response to DSBs (Fig 6A). Conducting a similar pull‐down (PD) but starting with His6‐Sumo2‐expressing cells, we could readily detect DNA damage‐dependent sumoylation of endogenous separase (Fig 6B). Although separase contains three regions that match the canonical sumoylation consensus motif, the sequence surrounding lysine 1034 was the most likely target according to bioinformatic prediction (Zhao et al, 2014). We therefore transfected cells to co‐express His6‐Sumo2 together with Myc‐tagged separase‐WT or separase‐K1034R. Consecutive DRB treatment, denaturing IMAC and Western blot analysis showed that Myc‐separase‐WT co‐purified with His6‐Sumo2, while the K1034R variant did hardly at all (Fig 6C). Sumoylation of wild‐type separase but not the K1034R variant was detectable even in the absence of Sumo overexpression and upon native isolation of the protease by Myc‐IP (Fig 6D). Thus, Lys‐1034 is a major, if not the only, target when separase is sumoylated in response to DSBs.

Figure 6. Sumoylation supports separase's role in DSB repair.

-

A, BSeparase is sumoylated in response to DSBs. HEK293T cells transfected to express His6‐separase (A) or His6‐Sumo2 (B) were treated with DRB or carrier solvent (− DRB) and then subjected to denaturing IMAC followed by immunoblotting of input samples and eluates using the indicated antibodies.

-

C, DLys‐1034 is a major target of DSB‐induced sumoylation of separase. HEK293T cells expressing His6‐Sumo2 (C) or Myc‐separase‐WT or separase‐K1034R (D) were DRB‐ or mock‐treated and subjected to denaturing IMAC or Myc‐IP, respectively. Input samples and eluates were immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies.

-

EMms21‐dependent in vitro sumoylation of separase at Lys‐1034. Myc beads were loaded with separase‐WT or separase‐K1034R or left empty (last lane), combined with recombinant Ubc9 and/or Mms21, as indicated, and incubated in the presence of His6‐Sumo2, Sae1‐Sae2, and ATP. Supernatant and washed beads were analyzed by Coomassie staining (lower panels) and immunoblotting (upper panels), respectively.

-

FCells expressing the indicated separase variants were DRB‐ or mock‐treated and then lysed. Lysates and chromatin pelleted therefrom were assessed by immunoblotting and Coomassie staining, as indicated. Note that the lanes shown in the upper panels, although not directly juxtaposed, nevertheless originate from the same gel.

-

GPreventing sumoylation of Lys‐1034 compromises separase's ability to support DSB repair. The indicated variants were probed for their ability to functionally replace endogenous separase in HDR as described in Fig 6A and B. Shown are averages (bars) of three independent experiments (dots) counting ≥ 100 cells each.

Source data are available online for this figure.

What could be the separase‐relevant Sumo E3 ligase? Mms21/Nse2 is the SUMO ligase of the Smc5/6 complex and has an established role in HDR (Potts & Yu, 2005). As a first step toward addressing this issue, we therefore asked whether Mms21 could sumoylate separase in vitro. Myc beads were loaded with Myc‐separase‐WT or Myc‐separase‐K1034R or left empty, combined with ATP, Sumo2, and the heterodimeric Sumo‐activating enzyme (E1: Sae1/Aos1‐Sae2/Uba2), and then incubated with recombinant Sumo‐conjugating enzyme (E2: Ubc9) and/or Mms21. Analysis of the bead‐less supernatant by SDS–PAGE and Coomassie staining revealed that the formation of high molecular weight Sumo conjugates occurred only when both E2 and E3 were present (Fig 6E, lower part). Importantly, Western blot analysis of the (washed) Myc beads demonstrated sumoylation of separase‐WT but not separase‐K1034R (Fig 6E, upper part). Thus, Lys‐1034 can serve as a target of Mms21 in a reconstituted system.

For functional analyses, firstly we assessed separase‐K1034R in its ability to associate with chromatin upon DNA damage. In contrast to separase‐WT and similar to separase‐KG, separase‐K1034R was unable to bind damaged, γH2AX‐positive chromatin pelleted by centrifugation from total cell lysates (Fig 6F). Secondly, we interrogated separase‐K1034R for its ability to functionally replace endogenous separase in the aforementioned DSB‐recovery assay (see above text and Fig 5B). Using separase‐WT and the KG variant as positive and negative control, respectively, we could show that separase‐K1034R largely failed to support cellular recovery from transient DRB treatment (Fig 6G). Taken together, this set of experiments establishes Lys‐1034 sumoylation, possibly by Mms21, as an integral element of separase's recruitment to DSBs and function in DDR.

SEPARASE +/− MEFs suffer from compromised DSB repair

We wanted to assess whether separase participates in HDR also in non‐transformed, primary cells and whether this function is conserved in mammals. Therefore, we created SEPARASE +/− mice and from these MEFs (see Fig EV4A–C and the Materials and Methods section for details). SEPARASE +/− MEFs were then compared to MEFs from corresponding wild‐type mice in their ability to recover from DRB‐inflicted DNA damage. In wild‐type MEFs, the fraction of cells with foci, which were positive for γH2AX and another damage marker, 53BP1, declined from 88.5% down to 32% within 24 h after DRB washout (Fig 7A and B). However, in heterozygotes the percentage of cells with these damage‐induced foci dropped from 90.5% to merely 76% during the same period. Consistent with persistent DNA damage and checkpoint‐mediated cell cycle arrest and in marked contrast to the wild type, the levels of γH2AX, phosphoChk2, and cyclin A2 hardly declined in the SEPARASE +/− MEFs during the 24 h of recovery from DRB (Fig 7C).

Figure EV4. Gene targeting of the separase locus.

- Diagrammatic representation of the relevant 5′ region of the SEPARASE locus. Exons are depicted as boxes with coding regions in gray. As indicated, the start (ATG) and stop (TGA) codons are located within exons E2 and E31, respectively. The regulating cassette from the TriTAUBi‐Bd plasmid is enclosed by a rtTS‐tTA cassette (Hayakawa et al, 2006). The selection markers NEO and URA are flanked by loxP sites (indicated by a P within red arrowheads). The minimum cytomegalovirus promoter (CMV), the tetO repeated sequences (tetO), all EcoRV (RV) sites, and the position of the Southern probe (see B) are indicated.

- Southern blot analysis of EcoRV‐digested genomic DNA from tails of wild‐type (WT = +) mice and those with the targeted mutation (TG) before and after Cre‐mediated deletion of the selection cassette (TG ΔNEO). See (A) for expected sizes of EcoRV fragments.

- Separase expression is halved in SEPARASE +/− MEFs. Northern blot analysis and densitometry were used to quantify the expression of SEPARASE mRNA normalized to the expression of ACTIN in total RNA preparations from SEPARASE +/+ versus SEPARASE +/− MEFs (n = 4). Values represent means ± standard deviations.

- No increase in aneuploidy in SEPARASE +/− MEFs. MEFs were treated with colcemid for 4 h and processed using standard methanol–acetic fixation followed by DAPI staining. MEFs from three embryos of each genotype and more than 100 metaphases per sample were counted. Values represent means ± standard deviations.

- No increase in lagging chromosomes in SEPARASE +/− MEFs. Cells passaged the day before were directly fixed and stained with DAPI. MEFs from three embryos of each genotype and more than 100 anaphases per sample were counted. Values represent means ± standard deviations.

Figure 7. Compromised DSB repair in SEPARASE +/− MEFs correlates with reduced damage‐induced cleavage of Rad21.

-

A, BSEPARASE +/+ and SEPARASE +/− MEFs were constitutively (− washout) or transiently exposed to DRB (+ washout) and then analyzed by IF for cells with γH2AX‐ and 53BP1‐positive foci. Shown are averages (bars) of three independent experiments (dots) counting ≥ 100 cells each. Scale bar = 5 μm.

-

CCell lysates from one experiment in (A) were analyzed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies.

-

D, ESEPARASE +/+ and SEPARASE +/− MEFs were treated with DRB (+) or carrier solvent (−) for the indicated times and then analyzed by immunoblotting of total cell lysates (D) and IPs using anti‐Rad21 or unspecific IgG (E). The lower right two lanes show in vitro‐expressed mouse Rad21 treated with hyperactive (SA) separase or a protease‐dead (PD) variant.

We also assessed damage‐induced Rad21 cleavage in SEPARASE +/− versus SEPARASE +/+ MEFs. γH2AX and cyclin A2 accumulated comparably with increasing duration of DRB treatment, indicating that the initial steps of damage response and the consequent checkpoint‐mediated cell cycle arrest were intact in both cell types (Fig 7D). Notably, Rad21‐IPs followed by immunoblotting revealed putative cleavage fragments (Fig 7E). Comparison of their mobility pattern with that of murine Rad21, which had been expressed and digested with active (SA) or protease‐dead (PD) separase in vitro (rightmost two lanes), confirmed their identities as bona fide products of separase's proteolytic activity. Importantly, Rad21 cleavage increased with increasing duration of DRB treatment and was always more pronounced in the wild type relative to the heterozygote (Fig 7E). Thus, taking an active part in DDR is not only a conserved feature of mammalian separase; this function is also strikingly dependent on SEPARASE dosage.

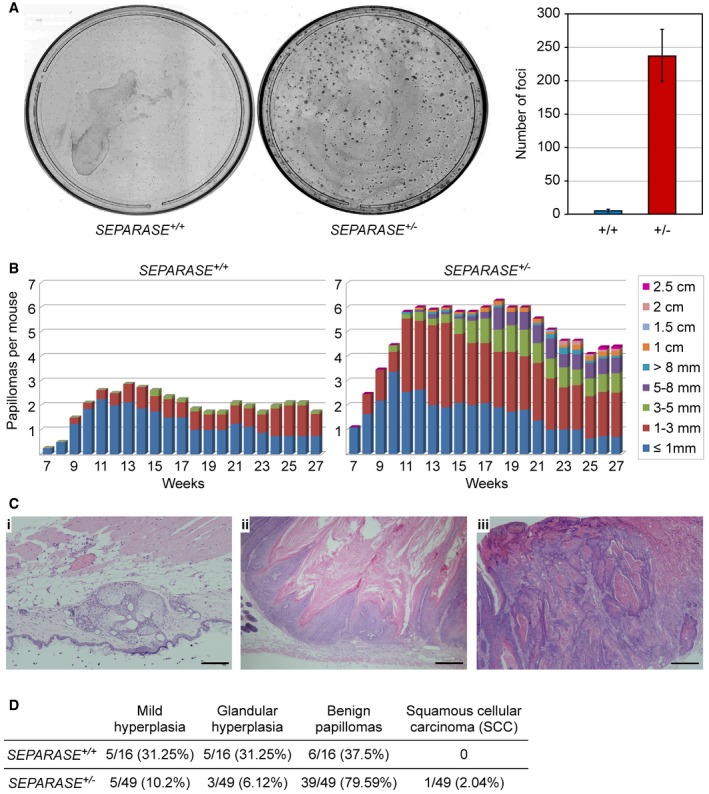

Reduced levels of separase predispose murine cells to oncogenic transformation

We have seen above that SEPARASE heterozygosity debilitates DSB repair. But does this have any physiological consequences on a cellular and organismal level? No differences in proliferation rate, cell cycle re‐entry, or senescence were detected between SEPARASE +/− and SEPARASE +/+ MEFs (Gutiérrez‐Caballero et al, unpublished observation). The heterozygous MEFs did also not exhibit any measurable increase in aneuploidies or lagging chromosomes in anaphase relative to wild‐type cells (Fig EV4D and E). Moreover, SEPARASE +/− mice presented a normal life span and were not predisposed to spontaneous tumorigenesis (Gutiérrez‐Caballero et al, unpublished observation). Given the strong connection between DSBs and carcinogenesis, we next compared SEPARASE +/− and SEPARASE +/+ MEFs in a cellular transformation assay, which involved transduction of two cooperating oncogenes, E1A and hRAS V12. Interestingly, we obtained a much higher focus‐forming activity of the SEPARASE +/− MEFs than of their wild‐type counterparts (Fig 8A). Thus, reduction in separase increases the susceptibility to neoplastic transformation in primary cell cultures.

Figure 8. Reduced levels of separase increases susceptibility to oncogenic transformation in mice.

- Transformation susceptibility of primary MEFs. SEPARASE +/+ versus SEPARASE +/− MEFs were infected to express E1A and hRasV12 and then subjected to a colony formation assay. Shown are representative images (left) and the graphical representation of the number of transformed foci (right) from two independent experiments (bars = standard deviations).

- Two‐stage DMBA (initiation) plus TPA (promotion) skin carcinogenesis. The number and size of skin papillomas are plotted against time for each genotype: SEPARASE +/+ (n = 8) versus SEPARASE +/− (n = 11).

- Representative hematoxylin‐ and eosin‐stained sections from SEPARASE +/− biopsies. (i) Glandular hyperplasia; (ii) benign papilloma; (iii) squamous cell carcinoma. Scale bars are 200 μm in (i) and 500 μm in (ii) and (iii).

- Quantitative histological assessment of the DMBA‐TPA skin carcinogenesis assay. Given are numbers of total, and corresponding percentage in brackets.

Encouraged by this phenotype, we next analyzed tumor initiation and progression in SEPARASE +/− versus SEPARASE +/+ mice using chemical induction. We chose the two‐step skin carcinogenesis protocol based on the use of DMBA as inductor and the mitogen TPA as tumor promoter (Abel et al, 2009). The first skin papillomas (initiation) appeared at the 7th week after DMBA application in both wild‐type and heterozygous mice (Fig 8B). However, the size and number of skin lesions differed markedly between SEPARASE +/+ and SEPARASE +/− mice during the whole time of the experiment (28 weeks). For instance, at 12 weeks after the beginning of the experiment wild‐type mice developed 2.7 tumors per animal compared to a mean of 6 in heterozygotes (2.2 times more). At 28 weeks after DMBA application, SEPARASE +/+ animals showed 1.7 papillomas per mice (mean) and SEPARASE +/− mice presented 4.4 papillomas (2.6 times more). Likewise, the papillomas exhibited a pronounced difference in size (Fig 8B). The majority of the wild‐type lesions (95%) were smaller than 3 mm, and none of them exceeded 5 mm. However, 25% of SEPARASE +/− papillomas were larger than 5 mm. To further investigate malignancy, we analyzed tumor histology (Fig 8C and D). In the wild type, this showed that a high proportion of lesions (62.5%) corresponded to small hyperplasias of the epidermis or glandular tissue, while the rest (37.5%) were defined as benign papillomas. Conversely, in the heterozygous mice only a small percentage (16.3%) of the lesions was classified as mild epidermal or glandular hyperplasias, whereas a large fraction was defined as benign papillomas (79.6%). Furthermore, one tumor (2%) corresponded to a malignant lesion, i.e., a squamous cellular carcinoma (Fig 8C and D). We conclude that SEPARASE is haploinsufficient in that the presence of its gene in only one copy strongly promotes formation and progression of chemically induced skin tumors in mice.

Discussion

We show here that mammalian separase has an important function for the repair of DSBs by HDR. Fulfilling this function involves the tethering of separase to the DNA lesions where it becomes proteolytically active to locally cleave cohesin. Together with previous studies on yeasts (Nagao et al, 2004; McAleenan et al, 2013), our work now firmly establishes that promotion of HDR is a conserved interphase function of separase. At first sight, these findings seem to be at odds with the well‐documented facts that cohesin also accumulates at DSBs and supports their repair (Kim et al, 2002; Strom et al, 2004; Unal et al, 2004; Potts et al, 2006). However, when assessing the roles of cohesin and separase side by side in the same in vivo assay, we indeed find both to be required for efficient HDR (Fig 2D and E). How can these observations be reconciled with each other? Actually, proteolytic removal of cohesin does not exclude its simultaneous hyper‐recruitment but will merely result in heightened turnover of cohesin at DSBs. These increased dynamics might be necessary for effective repair by facilitating close juxtaposition of sister chromatids while simultaneously granting the repair machinery access to catalyze DNA end resection, strand invasion, DNA synthesis and resolution of recombination intermediates. Consistent with this model, Aragón et al demonstrated compromised DSB resection and repair efficiency upon expression of separase‐resistant, non‐cleavable Rad21 in budding yeast (McAleenan et al, 2013).

We were able to image some chromosome spreads of DRB‐treated cells that expressed a histone‐based separase activity sensor and had slipped into mitosis despite persistent DNA damage (Fig 3C). This revealed for the first time that the activation of separase does indeed occur not globally but only locally. Nevertheless, given that separase‐dependent reduction in cohesin occurs only within ≈10 kb around the DSB in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (McAleenan et al, 2013), the zones of cleaved sensor were surprisingly large, coinciding largely with the γH2AX signal, which is known to spread up to almost 2 Mb (Iacovoni et al, 2010). Remarkably, sensor cleavage, much like the γH2AX signals, did not spread to the sister but only along the damaged chromatid, arguing that separase might not diffuse freely from the DSB but be recruited over large distances and stay immobilized. Future ChIP‐qPCR experiments will clarify this issue.

While the recruitment of yeast separase to DSBs remains enigmatic, we begin here to elucidate this issue for human separase. We identify three novel PTMs, an NES‐inactivating phosphorylation, Arg‐methylation within a conserved RG‐repeat motif, and sumoylation of Lys‐1034, all of which are induced by DSBs and necessary for the association of separase with γH2AX‐positive chromatin. Moreover, we reconstitute these separase PTMs in vitro by using the DDR‐relevant enzymes ATM, PRMT1, and Mms21, respectively. While this answers some questions, others remain to be addressed: Do ATM, PRMT1, and Mms21 act on separase in vivo? What represents the anchor for modified separase on damaged DNA? How can the selective recruitment of separase to DSBs of only postreplicative cells be explained? And, most importantly, how is tethered separase activated at DSBs while simultaneously preventing global activation of the protease, which would result in premature loss of cohesion? In regard to this last question, it is interesting to note that an important role of the APC/C coactivator Cdh1 in HDR has recently emerged (Lafranchi et al, 2014; Ha et al, 2017). Given that the separase inhibitor securin is slowly turned over in DRB‐treated G2 cells in an APC/CCdh1‐dependent manner (Hellmuth et al, 2014), it is tempting to speculate that DSB‐associated separase might be activated by the Cdh1‐form of this E3 ubiquitin ligase.

Studying cellular transformation in E1A‐ and hRAS V12‐expressing MEFs as well as chemically induced skin carcinogenesis in mice, we demonstrate that SEPARASE heterozygosity strongly predisposes murine cells to oncogenic transformation. At the same time, these cells show no signs of numerical chromosomal instability but are clearly compromised in recovery from transient DRB treatment. Thus, HDR seems to be more sensitive to limiting amounts of separase than sister chromatid separation. Replacing SEPARASE by our HDR‐defective alleles should clarify whether the association of SEPARASE heterozygosity with cancer might generally be explained by weakened DSB repair rather than anaphase problems. A recent study reports frequent mutations of SEPARASE and the cohesin subunit STAG2 in transitional cell carcinoma, the predominant form of bladder cancer (Guo et al, 2013). With HDR being the only cellular function in which cohesin and its nemesis separase collaborate, it will be interesting to test whether the corresponding alleles might exhibit selective defects in HDR.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used for immunoblotting according to standard protocols: rabbit anti‐separase (1:1,500; Stemmann et al, 2001), mouse anti‐securin (1:1,000; MBL), mouse anti‐Flag M2 (1:2,000; Sigma‐Aldrich), mouse anti‐Myc (hybridoma supernatant 1:50; DSHB; 9E10), mouse anti‐SUMO2 (protein G‐purified hybridoma supernatant conc. 1.67 mg/ml diluted 1:500; DSHB; clone 8A2), mouse anti‐RGS‐His (1:1,000; Qiagen), rabbit anti‐phosphoSer139‐histone H2A.X (γH2AX; 1:5,000; Millipore), rabbit anti‐asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA; 1:100; Acris), mouse anti‐cyclin B1 (1:1,000; Millipore), mouse anti‐topoisomerase IIα (1:1,000; Enzo Life Sciences), mouse anti‐cyclin A2 (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti‐phosphoSerine (1:1,000; Invitrogen), rabbit anti‐phosphoThr68‐Chk2 (1:800; Cell Signaling), mouse anti‐Rad21 (1:800; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; B‐2), rabbit anti‐Rad21 (1:1,000; Bethyl; A300‐080A), rabbit anti‐Smc1 (1:1,000; Bethyl) mouse anti‐Wapl (hybridoma supernatant 1:500; raised against the first 88 aa; clone D9), mouse anti‐GFP (hybridoma supernatant 1:2,000; gift from D. van Essen and S. Saccani), goat anti‐GST (1:800; gift from D. Boos), rat anti‐HA (1:2,000; Roche; clone 3F10), and mouse anti‐α‐tubulin (hybridoma supernatant 1:200; DSHB; 12G10). For immunoprecipitation experiments, the following affinity matrices and antibodies were used: mouse anti‐Myc agarose (Sigma‐Aldrich), mouse anti‐Rad21 coupled to protein G sepharose (GE Healthcare), rabbit anti‐separase (Hellmuth et al, 2014) coupled to protein A sepharose (GE healthcare), and an GFP‐binding, Escherichia coli‐expressed, metal ion affinity‐purified camel antibody fragment covalently coupled to NHS‐sepharose (GE Healthcare). For ChIP experiments, rabbit anti‐γH2AX, rabbit anti‐separase (Hellmuth et al, 2014), or non‐specific rabbit IgG (Bethyl) coupled to protein A agarose containing salmon sperm DNA (Millipore) was used. For non‐covalent coupling of antibodies to beads, 10 μl of the respective matrix was rotated with 2–5 μg antibody for 90 min at room temperature and then washed three times with lysis buffer. For IFM, newly raised rabbit anti‐separase (aa1,305–1,573; this study), mouse anti‐Hec1 (1:800; Genetex), mouse anti‐Myc (1:1,000; Millipore; 4A6), rabbit anti‐MDC1 (1:200; Abcam), rabbit anti‐53BP1 (1:500; Santa Cruz), mouse anti‐Nup153 (1:1,000; Abcam), rabbit anti‐γH2AX (1:1,000; Millipore), and mouse anti‐γH2AX (1:2,500; Millipore) were used. For the detection of eGFP‐tagged separase variants (Figs 4D and EV3A) and eGFP‐ and mCherry‐tagged separase activity sensor (Fig 3C), autofluorescence was imaged. Secondary antibodies (all 1:500) were as follows: Cy3 donkey anti‐guinea pig IgG, Cy5 goat anti‐rabbit IgG, and Cy5 goat anti‐mouse IgG (all from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories), and Marina Blue goat anti‐rabbit IgG, Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti‐rabbit IgG, and Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti‐mouse IgG (all from Invitrogen).

Cell lines

For stable, inducible expression of Myc6‐separase, a single copy of the corresponding transgene was stably integrated into a HEK293‐FlpIn‐TRex line (Invitrogen) by selection of clones at 150 μg/ml hygromycin B (Figs 1D and E, 3, EV1B, C, and F, and EV2C–E). A second, constitutively expressed transgene encoding histone H2B‐mCherry‐Rad21107–268‐eGFP (separase sensor) was integrated via ϕC31‐mediated site‐specific recombination followed by selection at 270 μg/ml G418 sulfate (Sigma‐Aldrich). Induction of transgenic Myc6‐separase was done using 0.2–1 μg/ml doxycycline (Dox; Sigma‐Aldrich) for 10–14 h. All human cells were cultured in DMEM (GE Healthcare) supplemented with 10% FCS (Sigma‐Aldrich) at 37°C and 5% CO2. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were cultivated in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 1% non‐essential amino acids, and 1% glutamine. Experiments shown in Fig 7 were performed during the third passage. For transient, inducible expression of Myc6‐separase variants [WT, RG>KG (R1423, 1425, 1427, 1429K), NESmut (1661‐AQEAPGDAPA‐1670 instead of 1661‐LQEMPGDVPL‐1670), superNES (1749‐DIDELALKFAGLDL‐1762 instead of 1749‐SLQEMPGDVPLARI‐1762), S1660A, S1660D, and K1034R], HEK293‐FlpIn‐TRex (Figs 4A, B, and F, 5, and 6C, D, F, and G) or HeLaK cells (Figs 4D, and EV3A and B) were transfected with the corresponding pcDNA5‐based plasmids using a calcium phosphate‐based method or Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. To enrich sumoylated separase species, in vivo expression plasmids for RGS‐His6‐tagged SUMO2 (kindly provided by S. Müller; Fig 6B and C) or RGS‐His6‐tagged separase‐WT (Fig 6A) were transfected into HEK293‐FlpIn‐TRex cells. To introduce multiple site‐specific DSBs, HEK293‐FlpIn‐TRex cells were transiently transfected with pCS2 plasmid to express FLAG3‐AsiSI‐ER (Figs 1B–E, 3, EV1A–C and F, and EV2E). Alternatively, a single DSB was inflicted by transient transfection of a pcDNA3‐based plasmid into U2OS cells (Figs 2, and EV2G and F) to express I‐SceI‐ER. In both cases, cells were subsequently treated with OHT.

Cell treatments

For synchronization at the G1/S boundary, cells were treated with 2 mM thymidine (Sigma‐Aldrich) for 20 h. To introduce DNA damage specifically in G2, cells released from a single thymidine block for 4–6 h were treated with 0.5–1 μM doxorubicin (DRB; LC Laboratories) or, in case of FLAG3‐ER‐AsiSI or HA‐ER‐I‐SceI expression, with 1 μM 4‐hydroxytamoxifen (OHT; Sigma‐Aldrich) for 4 h unless specified otherwise. Prior to ChIP, cells were exposed to OHT for 12 h. To achieve a DNA damage checkpoint‐independent G2 arrest, the Cdk1‐inhibitor RO3306 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added to 10 μM 4–6 h after release from a thymidine arrest in all cases but the washout (Figs 5, 6G, and 7A–C) and sumoylation experiments (Fig 6A–D). For the inhibition of the ATM kinase, KU‐55933 (LC Laboratories) was given at the time of DRB addition for 4 h at 2 μM (Fig EV3A and B) or for 12 h at 0.3 μM (Fig 4C). To inflict DNA damage on G1 cells, DSB‐introducing agents (but no RO3306) were added 13 h after release from a G1/S block. For doxorubicin (DRB) washout experiments, thymidine pre‐synchronized cells were DRB‐treated for 1 h, detached from the culture plate, and washed five times with fresh medium. Thereafter, cells were divided for the indicated treatments (Figs 5, 6G, and 7A–C) and DRB was re‐added to samples “without” DRB washout. Approximately 24 h after DRB removal, cells were analyzed for successful DNA damage repair or persisting γH2AX‐ and MDC1‐ or 53BP1‐positive foci.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry of propidium iodide‐stained DNA/cells was done as described (Hellmuth et al, 2014). To measure the amount of GFP fluorescence (Figs 2B and D, and EV2G) 48 h after infliction of a single DSB by OHT addition, cells were trypsinized, resuspended in fresh media, mixed 2:1 with 10% formaldehyde, and immediately analyzed as described (Gunn & Stark, 2012). The cell population with increased GFP fluorescence above background was gated in a logarithmic FL2/FL1 plot to determine the percentage of GFP‐positive cells.

Immunoprecipitation

1 × 107 cells were lysed with a Dounce homogenizer in 1 ml lysis buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.7, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaF, 20 mM β‐glycerophosphate, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton X‐100, 5% glycerol), combined with Benzonase® (ad 30 U/l; Santa Cruz), and incubated on ice for 2 h. To preserve separase phosphorylation status (Fig 4A–C), lysis buffer was additionally supplemented with 1 μM okadaic acid (Sigma‐Aldrich) and 1 μM microcystin LR (Alexis Biochemicals). “Whole cell lysates” were centrifuged at 16,000 g for 30 min to give “high‐speed supernatant” and at 2,500 g for 10 min to give “low‐speed supernatant” and a chromatin pellet, which was resolubilized in lysis buffer supplemented with additional 400 mM NaCl as well as 50 mM EDTA to give a “chromatin extract”. With few exceptions (see below), 10 μl of antibody carrying beads was incubated with 1 ml “whole cell lysate” for 4 h at 4°C and washed 5× with lysis buffer before bound proteins were eluted by Tev‐protease treatment in Tev‐cleavage buffer (10 mM HEPES‐KOH pH 7.7, 50 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaF, 1 mM EGTA, 20% glycerol) for 40 min at RT (Fig 4G) or by boiling in non‐reducing SDS sample buffer (all other cases). To enrich soluble sensor‐ and Rad21‐cleavage fragments relative to the chromatin‐associated full‐length proteins (Figs 3A and B, and 7D and E), “low‐speed supernatant” instead of “whole cell lysate” was used for the GFP‐ and Rad21‐IPs, respectively. To purify separase as a substrate for Arg‐methylation or phosphorylation assays (Fig 4E and G), “high‐speed supernatant” instead of “whole cell lysate” was used for the Myc‐IP. To enrich Arg‐methylated separase (Fig 4F), “chromatin extract” instead of “whole cell lysate” was used for the Myc‐IP.

RNA interference

For efficient knock‐down, cells were transfected with calcium phosphate or RNAiMax® (Invitrogen) and 70 nM of single siRNA duplex of SEP‐01: 5′‐AACUGUUCUACCUCCAAGGUUAGAUUU‐3′ (was generally used unless stated otherwise), SEP‐02: 5′‐GGACUGCCCUGCACACCUA‐3′, SEP‐03: 5′‐GAAGAUCGUUUCCUAUACA‐3′, SEP‐04: 5′‐GAACUUCAGUGAUGACAGU‐3′, SEP‐05: 5′‐GCUGUCAGAUAGUUGAUUU‐3′, or SMC1_ORF1: 5′‐AAGAAAGUAGAGACAGA‐3′. In case of two siRNAs targeting the identical RNA, 40 nM each was used: (i) RAD21_3′UTR1: 5′‐ACUCAGACUUCAGUGUAUA‐3′, and (ii) RAD21_3′UTR2: 5′‐AGGACAGACUGAUGGGAAA‐3′; and (i) WAPL1: 5′‐CGGACUACCCUUAGCACAA‐3′, and (ii) WAPL2: 5′‐GGUUAAGUGUUCCUCUUAU‐3′. Transfected cells were grown for 12–24 h before synchronization procedures were applied. Luciferase siRNA (GL2) was used as negative control in variable concentrations.

Multiplex PCR

PCRs were performed with the same set of primers and conditions as for qPCR (see below) except for the use of self‐made Taq polymerase and 4 μl immunoprecipitated DNA or 1 μl input DNA as template. Amplified fragments were separated on 6% PAGs (2.7% cross‐linker; 8 × 10 × 0.1 cm) in 0.5× TBE buffer (44.5 mM Tris, 44.5 boric acid, 1 mM EDTA) at 100 V for 45 min. Gels were stained in ethidium bromide (1 μg/ml), destained in H2O and finally analyzed under UV light (Gene Flash, Syngene Bio Imaging).

qPCR

For ChIP‐qPCR, immunoprecipitated and input DNA were analyzed in triplicates by real‐time qPCR using the following primers: CGGGTTGGGCTTGAGTGAGG and AACCTGCCCCAACCCGATCA for DSB1‐A, GGAGTCGGCCGGGATCACAT and CCTTGCAAACCAGTCCTCGTCC for DSB1‐B, GGAGTCGGCCGGGATCACAT and CCCCACAGCTTGCCCATCCT for DSB1‐C, AGGACTGGTTTGCAAGGATG and ACCCCCATCTCAAATGACAA for DSB1‐D, GGGACATGTGAGACTGAAGAAGG and ACGCCTCTCCCACTCCCTCT for DSB1‐E, AACTTTAGGATGGGGGCTGCT and GCCATAACAGAGGGTGGAAA for DSB1‐F, TGCCGGTCTCCTAGAAGTTTG and GCGCTTGATTTCCCTGAGT for DSB2‐A, and CCCATCTCAACCTCCACACT and CTTGTCCAGATTCGCTGTGA for “no DSB”. The AsiSI‐induced DSB sites are on chromosome 1 (DSB1) and chromosome 6 (DSB2). The AsiSI‐negative locus (“no DSB”) maps to chromosome 22. PCRs were assembled with Maxima SYBR® Green/ROX master mix (Fermentas), 300 nM forward/reverse primer, and 2 μl template DNA in 48‐well plates (Applied Bioscience). qPCR was performed at 59°C annealing temperature for 40 cycles in a StepOne Real Time PCR system (Applied Bioscience). IP efficiency was calculated as percentage of input DNA immunoprecipitated (adjusted to 100%) with the following formula:

Skin chemical carcinogenesis, histology, and immunohistochemistry

For the induction of skin papillomas, a previously described multi‐stage carcinogenesis model was followed (Abel et al, 2009). Briefly, the back skin of 8‐week‐old mice was shaved and painted with a single dose of 25 μg DMBA (Sigma) dissolved in acetone 24 h later. Forty‐eight hours later, tumor growth was promoted by applying 12.5 μg of TPA (Sigma) dissolved in acetone twice a week for a period of 12 weeks. The number and characteristics of the skin lesions were annotated twice a week.

Skin papillomas and surrounding skin were fixed in 10% formaldehyde for 24 h and subsequently embedded in paraffin. Serial sections of 5 μm were stained with hematoxylin and eosin following standard procedures.

Additional experimental procedures are described in “Appendix Supplementary Materials and Methods”.

Author contributions

CG‐C and EL conducted all the mouse work (Figs 8 and EV4) and isolated the MEFs used for Fig 7. AMP and OS designed the research and wrote the paper. SH co‐designed the research, carried out all experiments except for those shown in Figs 8 and EV4 and contributed to writing of the paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Appendix

Expanded View Figures PDF

Review Process File

Source Data for Figure 6F

Acknowledgements

We thank Gaëlle Legube, Lisa Mohr, and Stefan Müller for plasmids; Maria Jasin and Jeremy Stark for DR‐GFP and EJ5‐GFP reporter U2OS cell lines, respectively; Markus Hermann for technical assistance; and Stefan Heidmann, Dominik Boos, and Boris Pfander for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by a grant (STE997/4‐2) from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) to O.S. and by a grant (BFU2017‐89408‐R) from Ministerio de Economía y Competividad to A.M.P.

The EMBO Journal (2018) 37: e99184

Contributor Information

Alberto M Pendás, Email: amp@usal.es.

Olaf Stemmann, Email: olaf.stemmann@uni-bayreuth.de.

References

- Abel TW, Clark C, Bierie B, Chytil A, Aakre M, Gorska A, Moses HL (2009) GFAP‐Cre‐mediated activation of oncogenic K‐ras results in expansion of the subventricular zone and infiltrating glioma. Mol Cancer Res 7: 645–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert FM, Dery U, Masson JY, Richard S (2005) Arginine methylation of MRE11 by PRMT1 is required for DNA damage checkpoint control. Genes Dev 19: 671–676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boos D, Kuffer C, Lenobel R, Korner R, Stemmann O (2008) Phosphorylation‐dependent binding of cyclin B1 to a Cdc6‐like domain of human separase. J Biol Chem 283: 816–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buheitel J, Stemmann O (2013) Prophase pathway‐dependent removal of cohesin from human chromosomes requires opening of the Smc3‐Scc1 gate. EMBO J 32: 666–676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron P, Aymard F, Iacovoni JS, Briois S, Canitrot Y, Bugler B, Massip L, Losada A, Legube G (2012) Cohesin protects genes against gammaH2AX Induced by DNA double‐strand breaks. PLoS Genet 8: e1002460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chailleux C, Aymard F, Caron P, Daburon V, Courilleau C, Canitrot Y, Legube G, Trouche D (2014) Quantifying DNA double‐strand breaks induced by site‐specific endonucleases in living cells by ligation‐mediated purification. Nat Protoc 9: 517–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dery U, Coulombe Y, Rodrigue A, Stasiak A, Richard S, Masson JY (2008) A glycine‐arginine domain in control of the human MRE11 DNA repair protein. Mol Cell Biol 28: 3058–3069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finetti P, Guille A, Adelaide J, Birnbaum D, Chaffanet M, Bertucci F (2014) ESPL1 is a candidate oncogene of luminal B breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat 147: 51–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanty Y, Belotserkovskaya R, Coates J, Polo S, Miller KM, Jackson SP (2009) Mammalian SUMO E3‐ligases PIAS1 and PIAS4 promote responses to DNA double‐strand breaks. Nature 462: 935–939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn A, Stark JM (2012) I‐SceI‐based assays to examine distinct repair outcomes of mammalian chromosomal double strand breaks. Methods Mol Biol 920: 379–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo G, Sun X, Chen C, Wu S, Huang P, Li Z, Dean M, Huang Y, Jia W, Zhou Q, Tang A, Yang Z, Li X, Song P, Zhao X, Ye R, Zhang S, Lin Z, Qi M, Wan S et al (2013) Whole‐genome and whole‐exome sequencing of bladder cancer identifies frequent alterations in genes involved in sister chromatid cohesion and segregation. Nat Genet 45: 1459–1463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttler T, Madl T, Neumann P, Deichsel D, Corsini L, Monecke T, Ficner R, Sattler M, Gorlich D (2010) NES consensus redefined by structures of PKI‐type and Rev‐type nuclear export signals bound to CRM1. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 1367–1376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha K, Ma C, Lin H, Tang L, Lian Z, Zhao F, Li JM, Zhen B, Pei H, Han S, Malumbres M, Jin J, Chen H, Zhao Y, Zhu Q, Zhang P (2017) The anaphase promoting complex impacts repair choice by protecting ubiquitin signalling at DNA damage sites. Nat Commun 8: 15751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa T, Yusa K, Kouno M, Takeda J, Horie K (2006) Bloom's syndrome gene‐deficient phenotype in mouse primary cells induced by a modified tetracycline‐controlled trans‐silencer. Gene 369: 80–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmuth S, Bottger F, Pan C, Mann M, Stemmann O (2014) PP2A delays APC/C‐dependent degradation of separase‐associated but not free securin. EMBO J 33: 1134–1147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacovoni JS, Caron P, Lassadi I, Nicolas E, Massip L, Trouche D, Legube G (2010) High‐resolution profiling of gammaH2AX around DNA double strand breaks in the mammalian genome. EMBO J 29: 1446–1457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ST, Lim DS, Canman CE, Kastan MB (1999) Substrate specificities and identification of putative substrates of ATM kinase family members. J Biol Chem 274: 37538–37543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JS, Krasieva TB, LaMorte V, Taylor AM, Yokomori K (2002) Specific recruitment of human cohesin to laser‐induced DNA damage. J Biol Chem 277: 45149–45153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kueng S, Hegemann B, Peters BH, Lipp JJ, Schleiffer A, Mechtler K, Peters JM (2006) Wapl controls the dynamic association of cohesin with chromatin. Cell 127: 955–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafranchi L, de Boer HR, de Vries EG, Ong SE, Sartori AA, van Vugt MA (2014) APC/C(Cdh1) controls CtIP stability during the cell cycle and in response to DNA damage. EMBO J 33: 2860–2879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Rankin S, Yu H (2013) Phosphorylation‐enabled binding of SGO1‐PP2A to cohesin protects sororin and centromeric cohesion during mitosis. Nat Cell Biol 15: 40–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAleenan A, Clemente‐Blanco A, Cordon‐Preciado V, Sen N, Esteras M, Jarmuz A, Aragon L (2013) Post‐replicative repair involves separase‐dependent removal of the kleisin subunit of cohesin. Nature 493: 250–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer R, Fofanov V, Panigrahi A, Merchant F, Zhang N, Pati D (2009) Overexpression and mislocalization of the chromosomal segregation protein separase in multiple human cancers. Clin Cancer Res 15: 2703–2710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee M, Ge G, Zhang N, Huang E, Nakamura LV, Minor M, Fofanov V, Rao PH, Herron A, Pati D (2011) Separase loss of function cooperates with the loss of p53 in the initiation and progression of T‐ and B‐cell lymphoma, leukemia and aneuploidy in mice. PLoS One 6: e22167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee M, Byrd T, Brawley VS, Bielamowicz K, Li XN, Merchant F, Maitra S, Sumazin P, Fuller G, Kew Y, Sun D, Powell SZ, Ahmed N, Zhang N, Pati D (2014a) Overexpression and constitutive nuclear localization of cohesin protease Separase protein correlates with high incidence of relapse and reduced overall survival in glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurooncol 119: 27–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee M, Ge G, Zhang N, Edwards DG, Sumazin P, Sharan SK, Rao PH, Medina D, Pati D (2014b) MMTV‐Espl1 transgenic mice develop aneuploid, estrogen receptor alpha (ERalpha)‐positive mammary adenocarcinomas. Oncogene 33: 5511–5522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao K, Adachi Y, Yanagida M (2004) Separase‐mediated cleavage of cohesin at interphase is required for DNA repair. Nature 430: 1044–1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasmyth K, Haering CH (2009) Cohesin: its roles and mechanisms. Annu Rev Genet 43: 525–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama T, Sykora MM, Huis in ‘t Veld PJ, Mechtler K, Peters JM (2013) Aurora B and Cdk1 mediate Wapl activation and release of acetylated cohesin from chromosomes by phosphorylating Sororin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 13404–13409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obenauer JC, Cantley LC, Yaffe MB (2003) Scansite 2.0: proteome‐wide prediction of cell signaling interactions using short sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res 31: 3635–3641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce AJ, Johnson RD, Thompson LH, Jasin M (1999) XRCC3 promotes homology‐directed repair of DNA damage in mammalian cells. Genes Dev 13: 2633–2638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polo SE, Jackson SP (2011) Dynamics of DNA damage response proteins at DNA breaks: a focus on protein modifications. Genes Dev 25: 409–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts PR, Yu H (2005) Human MMS21/NSE2 is a SUMO ligase required for DNA repair. Mol Cell Biol 25: 7021–7032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts PR, Porteus MH, Yu H (2006) Human SMC5/6 complex promotes sister chromatid homologous recombination by recruiting the SMC1/3 cohesin complex to double‐strand breaks. EMBO J 25: 3377–3388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacher M, Pfander B, Hoege C, Jentsch S (2006) Control of Rad52 recombination activity by double‐strand break‐induced SUMO modification. Nat Cell Biol 8: 1284–1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard JL, Amatruda JF, Finkelstein D, Ziai J, Finley KR, Stern HM, Chiang K, Hersey C, Barut B, Freeman JL, Lee C, Glickman JN, Kutok JL, Aster JC, Zon LI (2007) A mutation in separase causes genome instability and increased susceptibility to epithelial cancer. Genes Dev 21: 55–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjogren C, Nasmyth K (2001) Sister chromatid cohesion is required for postreplicative double‐strand break repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Curr Biol 11: 991–995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemmann O, Zou H, Gerber SA, Gygi SP, Kirschner MW (2001) Dual inhibition of sister chromatid separation at metaphase. Cell 107: 715–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom L, Lindroos HB, Shirahige K, Sjogren C (2004) Postreplicative recruitment of cohesin to double‐strand breaks is required for DNA repair. Mol Cell 16: 1003–1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom L, Karlsson C, Lindroos HB, Wedahl S, Katou Y, Shirahige K, Sjogren C (2007) Postreplicative formation of cohesion is required for repair and induced by a single DNA break. Science 317: 242–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Yu H, Zou H (2006) Nuclear exclusion of separase prevents cohesin cleavage in interphase cells. Cell Cycle 5: 2537–2542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thandapani P, O'Connor TR, Bailey TL, Richard S (2013) Defining the RGG/RG motif. Mol Cell 50: 613–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann F, Wernic D, Poupart MA, Koonin EV, Nasmyth K (2000) Cleavage of cohesin by the CD clan protease separin triggers anaphase in yeast. Cell 103: 375–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unal E, Arbel‐Eden A, Sattler U, Shroff R, Lichten M, Haber JE, Koshland D (2004) DNA damage response pathway uses histone modification to assemble a double‐strand break‐specific cohesin domain. Mol Cell 16: 991–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unal E, Heidinger‐Pauli JM, Koshland D (2007) DNA double‐strand breaks trigger genome‐wide sister‐chromatid cohesion through Eco1 (Ctf7). Science 317: 245–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Huang ZQ, Xia L, Feng Q, Erdjument‐Bromage H, Strahl BD, Briggs SD, Allis CD, Wong J, Tempst P, Zhang Y (2001) Methylation of histone H4 at arginine 3 facilitating transcriptional activation by nuclear hormone receptor. Science 293: 853–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Xiong Y (2001) A p53 amino‐terminal nuclear export signal inhibited by DNA damage‐induced phosphorylation. Science 292: 1910–1915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Ge G, Meyer R, Sethi S, Basu D, Pradhan S, Zhao YJ, Li XN, Cai WW, El‐Naggar AK, Baladandayuthapani V, Kittrell FS, Rao PH, Medina D, Pati D (2008) Overexpression of Separase induces aneuploidy and mammary tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 13033–13038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q, Xie Y, Zheng Y, Jiang S, Liu W, Mu W, Liu Z, Zhao Y, Xue Y, Ren J (2014) GPS‐SUMO: a tool for the prediction of sumoylation sites and SUMO‐interaction motifs. Nucleic Acids Res 42: W325–W330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix

Expanded View Figures PDF

Review Process File

Source Data for Figure 6F