Abstract

This systematic review assessed coping and adjustment in caregivers of all ages to provide a synthesis of existing literature in the context of methodological approaches and underlying theory. Four databases were searched. Reference lists, citations and experts were consulted. In total, 27 studies (13 quantitative and 14 qualitative) were included. Coping factors associated with adjustment (problem- versus emotion-focussed coping and cognitive strategies) and psychosocial factors associated with physiological adjustment (trait anxiety, coping style and social support) were identified. Results raised methodological issues. Future research requires physiological adjustment measures and longitudinal assessment of the long-term impact of childhood caregiving. Findings inform future caregiver research and interventions.

Keywords: adjustment, caregiver, caregiving, carer, coping

Background

The impact of informal caregiving has increasingly become the focus of academic research and social policy interest, as health services offer management of what were once serious health conditions, individuals are able to remain in their home while receiving care, increasing the need for family members to provide assistance (Schubart, 2014). Carers can be any age (from young child to older adult) and may have various tasks and responsibilities including domestic care, general care, personal/intimate care and emotional support (Pakenham et al., 2006). Recent census findings (Office for National Statistics, 2012) reported approximately 6.5 million carers in the United Kingdom, providing between 1 and 50+ hours of weekly care, with an average of 24.4 hours per week (Revenson et al., 2016).

Studies have investigated the psychosocial outcomes of caregiving. Compared to non-caregivers, older adult carers report increased stress and depression, as well as lower levels of subjective well-being and self-efficacy (Pinquart and Sörensen, 2003; Revenson et al., 2016). Providing informal care can impact social activities and marital dynamics in adult caregivers (Matthews, 2018). Caring for individuals with specific health conditions (such as dementia) can cause unique challenges, for example, being subjected to physical or verbal agression (Dodge and Kiecolt-Glaser, 2016). Furthermore, physical outcomes associated with caregiver stress in both elderly and non-elderly carers include changes in endocrine and immune functioning (Vedhara et al., 1999, 2002). Specifically, chronically raised salivary cortisol has been linked to poorer immunity (Pruessner et al., 1999), and young parents caring for a child with developmental disabilities have demonstrated a poorer antibody response to influenza vaccination (Gallagher et al., 2009). Lovell et al. (2012) investigated psychosocial, endocrine and immune outcomes in young adults caring for a child with autism spectrum disorder or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Parents reported higher psychological distress, perceived stress, anxiety and depression than non-caregivers and more physical health problems. Although diurnal cortisol secretion did not differ between the two groups, caregivers demonstrated elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), indicating greater inflammatory disease risk. In addition to endocrine and immune findings, health problems including back injuries, arthritis, high blood pressure, gastric ulcers and headaches are also associated with caregiver stress in carers aged 35–76 years old (Sawatzky and Fowler-Kerry, 2003). To date, research has considered physical outcomes of adult rather than young carers, defined as anyone under 18 years providing care (Becker et al., 2000).

While findings indicate the psychological and physical detriments of caregiving, many caregivers cope effectively without evidence of negative impacts (Cohen et al., 2002; Garity, 1997). Positive consequences have been identified; spousal caregivers of cancer patients have reported enhanced relationships, feeling rewarded, experiencing a sense of personal growth and satisfaction (Li and Loke, 2013). Furthermore, informal caregivers of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis report both positive and negative experiences (Sandstedt et al., 2018). Young carers report feeling proud of their role, the development of valuable skills and increased maturity and independence (Cass et al., 2009). This suggests not all caregiver outcomes are detrimental and that resilience may enable effective coping, whereby individuals demonstrate adjustment. In the current review, coping is considered a process leading to adjustment, where adjustment encompasses the psychophysiological outcomes of coping; positive adjustment is defined as the adaptive response to a challenge, across physical, interpersonal, cognitive, emotional and behavioural domains (Larsen and Lubkin, 2009). The term adjustment was used in this review as it encapsulated a number of terms that relate to outcomes in the caregiving context and is most often used in this particular field.

Many studies offer theoretical explanations of caregiver outcomes based on the Transactional model of Stress and Coping (TSC; Lazarus and Folkman, 1984), where coping is defined as a process of ‘constantly changing cognitive and behavioural efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands… appraised as taxing or exceeding [personal] resources’ (p. 141). Inherent in this process are coping responses, typically problem-focussed (‘actions that change the…relationship between the person and the environment’), emotion-focussed (‘actions that [change] the meaning of that relationship’ such as avoidance, distraction and minimisation) or cognitive (influencing stress and emotion by ‘re-appraisal of the person-environment relationship’) (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984: 77). Haley et al. (1987) reported that appraisal and coping responses were significant predictors of outcomes in adult dementia caregivers. This has been further demonstrated where caregiving factors, cognitive appraisal, coping strategies and coping resources were predictors of adjustment in adult multiple sclerosis (MS) carers (Pakenham, 2001).

Use of problem-focussed coping is associated with better caregiver adjustment than emotion-focussed coping (Pakenham, 2001). Branscum (2011) suggests that adverse caregiving effects in adults can be lessened with adequate social support and problem-focussed coping. Yet, defining psychological concepts such as coping and adjustment is challenging in any population, and the TSC model has been criticised for its oversimplification and disregard of the situational nature of coping (Schwarzer and Schwarzer, 1996). Others have incorporated multi-dimensional approaches and highlight that the effectiveness of strategies may vary depending on the situation and stressor encountered (Carver et al., 1989). Similarly, Skinner (2007) proposed 12 ‘families’ of coping based on function and contribution to adaptation. At a physiological level, the concepts of allostasis and allostatic load are a well-accepted explanation for adjustment in underlying mechanisms resulting in differential health outcomes (McEwen, 1998; Sterling and Eyer, 1988). These concepts have been applied to a model of adjustment in investigating the physical impact of caregiving (Vedhara et al., 1999, 2002).

While empirical studies have considered factors associated with adjustment and coping in the caregiving population, reviews conducted in this area predominantly describe or collate findings assessing the needs of caregivers, providing data on prevalence and impact. The literature has not been systematically reviewed to draw conclusions about the factors associated with coping behaviours. Reviews that have considered coping and adjustment in caregivers are now outdated (Low et al., 1999) or focus on specific caregiving populations (e.g. stroke caregivers; Del-Pino-Casado et al., 2011).

The aim of this study was to assess coping and adjustment across all caregiver ages and conditions cared for, using a systematic review. Identifying coping factors associated with adjustment or stress resilience can inform future research and health providers aiming to support carers.

Method

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; see Supplemental Material) guidelines were used (Moher et al., 2010).

Search strategy

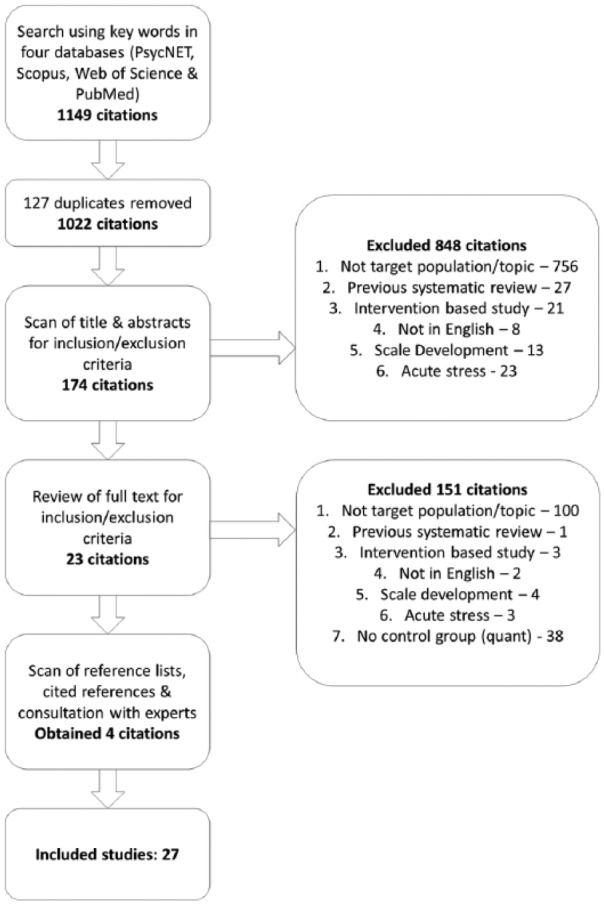

Four online databases (PsycNET, Web of Science, PubMed and Scopus) were searched. References of retrieved papers, previous reviews and books were scanned. Experts in the area were consulted via email where appropriate. A search of cited reference lists was also carried out. Figure 1 details the search process.

Figure 1.

Search process.

Searches were conducted (5 November 2015, repeated 9 October 2017 and 7 January 2018) using keywords (coping, adjustment, outcomes and caregivers) and Boolean operators. Some search terms differed between databases due to the availability of index terms and database-specific filters (e.g. PsycNET search: Coping behaviour AND Adjustment OR Outcomes AND caregiv* NOT intervention. Web of Science search: Coping AND Adjustment OR Outcomes AND ‘Family caregivers’ NOT intervention*).

There were no publication date limits. Both quantitative and qualitative studies were reviewed.

Study selection

Duplicates were removed and results were reviewed based on titles and abstracts. Full texts were retrieved for eligible studies and further reviewed for inclusion and exclusion criteria. Data were extracted from articles using a piloted data extraction form that included information about aims, design, sample, measures and findings.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for quantitative studies were that they (1) reported experiences of informal caregivers; (2) investigated chronic stress (a stressor that is gradual, long-term and continuous); (3) measured coping and/or outcomes; and (4) included a control or comparison group. Inclusion criteria for qualitative studies were that they (1) reported the experiences of informal caregivers; (2) investigated chronic stress; and (3) discussed coping style/strategies and outcomes. A control or comparison group was required for quantitative studies to reflect methodological quality, but was not required for qualitative studies.

Studies were therefore excluded if they (1) were not the target population or topic (e.g. animal studies, formal caregivers or did not investigate coping); (2) were a previous systematic review; (3) were an intervention based study; (4) were not written in English and a translation was not available; (5) were a scale development study; (6) investigated acute stress; or (7) did not have a control group (for quantitative studies).

Two reviewers assessed articles against criteria; checking and confirmation was conducted by the second reviewer, and disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Quality ratings

All selected studies were subjected to quality appraisal. Quantitative studies were rated for quality across four dimensions – sample, attrition, measurement and analysis – using 11 criteria developed by Laisné et al. (2012). Studies were rated zero (no; partial) and one (yes); therefore, the maximum score was 11. All studies reached moderate (>5) to high quality (>8); none were excluded.

Qualitative studies were rated using Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields (Kmet et al., 2004). Ten criteria were used to assess design, sampling, data collection and analysis and were rated zero (no), one (partial) and two (yes); maximum score was 20. All qualitative studies were rated as high (>15).

Results

A total of 27 empirical papers met inclusion criteria; 13 used a quantitative and 14 used a qualitative methodology (see Tables 1 and 2 in Supplemental Material). Publication years ranged from 1996 to 2015. All quantitative studies used self-report measures to collect data and were predominantly cross-sectional. One study was longitudinal (with a control group). All of the quantitative studies used a between-groups design (e.g. caregiver vs non-caregiver and dementia caregiver vs stroke caregiver). Controls and comparison groups comprised non-caregivers, caregivers of healthy individuals or caregivers of a comparison health condition. Qualitative data in all 14 studies were collected via semi-structured interview, with one study also using photo elicitation and another using observation. Qualitative analysis was mostly thematic, alongside interpretive phenomenological analysis, content analysis and grounded theory. One qualitative study was longitudinal and presented as a case study.

A total of 2084 participants were included, with a minimum of 1 participant and a maximum of 246. The minimum mean age was 17 years; maximum was 74 years. Care provided was in the context of a range of health conditions as indicated in Table 1, and caregivers were related to care recipients as grandparents, spouses, parents and offspring.

Table 1.

Health conditions and contexts of individuals cared for by caregivers.

| Health condition or context |

|---|

| Alzheimer’s disease/dementia |

| Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder |

| Autism spectrum condition (ASC) |

| Closed/traumatic brain injury |

| Human immunodeficiency virus |

| Intellectual disability |

| Lung transplant candidates |

| Mental illness |

| Multiple sclerosis |

| Pulmonary heart disease |

| Spinal cord injury |

| Stroke |

Findings from the 27 papers were synthesised using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Substantive insights were identified in four areas: (1) problem- versus emotion-focussed coping, (2) use of cognitive strategies, (3) factors associated with psychological adjustment and (4) factors associated with physiological adjustment. There were also clear methodological issues.

Use of problem- versus emotion-focussed coping

The studies in this review identified a number of coping strategies utilised by participants, categorised as problem- or emotion-focussed coping, in line with the definitions above.

Caregivers reported using fewer positive strategies and relied less on problem-focussed coping than non-caregivers (Mausbach et al., 2013; Pakenham and Bursnall, 2006). Some studies investigated the relationship between coping styles and adjustment. Mausbach et al. (2013) identified that carers using fewer positive strategies (e.g. engaging in pleasant activities and seeking social support) and greater negative coping strategies (e.g. self-blame and avoidance) reported poorer psychosocial outcomes and adjustment compared to non-caregivers. Negative impacts included increased depressive symptoms, negative affect, fear, hostility and sadness.

Problem-focussed coping was generally considered most adaptive and associated with less psychological distress and more positive outcomes (Bachanas et al., 2001; Pakenham and Bursnall, 2006). Ten studies reported examples of problem-focussed strategies adopted by caregivers. Some of these strategies were actions the caregiver took to reduce their burden (reducing work hours, using paid carers, accepting financial hardship, integrating care into family culture, daily routines, incorporating risk management into daily life, utilising social support and effectively planning activities and care; Dickson et al., 2012; Kita and Ito, 2013; McCausland Kurz and Cavanaugh, 2001; Sun, 2014; Williams et al., 2014). Other problem-focussed coping involved action or changes in behaviour surrounding the cared for person to reduce time and labour (e.g. coping with their physical limitations, engaging them in activities, lowering expectations of them, avoiding confrontation, finding humour, overseeing health and treatments and modifying communication methods). Finally, problem-focussed strategies included communicating with others and researching the health condition to increase a sense of control (Williams et al., 2014). Caregivers reported comparing their relative’s health through books and social media: communicating with schools and others in similar situations through online platforms or support groups and researching online about the cared for person’s condition (Le Dorze et al., 2009; McCausland Kurz and Cavanaugh, 2001; Sun, 2014; Williams et al., 2014). Although problem-focussed strategies were generally reported as most helpful and associated with more positive outcomes in caregivers, in many cases, these were not used more than emotion-focussed strategies.

Overall, studies that reported use of emotion-focussed coping strategies found associations with negative outcomes, with caregivers being less able to regulate their negative emotions compared to controls (Ruiz-Robledillo and Moya-Albiol, 2013). Figueiredo et al. (2014) found that greater use of emotional coping was associated with poorer mental health perception. Sander et al. (1997) report associations between greater use of emotion-focussed coping and levels of psychological and emotional distress. Others specify emotion-focussed techniques such as distraction and avoidance as being considered unhelpful by caregivers. Haley et al. (1996) reported that high levels of avoidance coping and low levels of approach coping were associated with greater depression and decreased life satisfaction. Wishful thinking and denial were also found to be related to greater psychological distress (Pakenham and Bursnall, 2006). Despite the generally reported negative impact of emotion-focussed coping, there were some exceptions where carers felt these strategies were helpful, including venting emotion, taking time out and having a ‘good cry’ to release emotional energy (Azman et al., 2017; Dickson et al., 2012; Figueiredo et al., 2014).

The quantitative longitudinal study examined the use of problem- and emotion-focussed coping in mothers caring for an adult child with an intellectual disability or mental health condition (Kim et al., 2003). Higher initial and increased use of problem-focussed coping predicted declining levels of burden and depressive symptoms. More use of emotion-focussed strategies increased burden and depressive symptoms and contributed to poorer parent–child relations.

Finally, three papers reported the use of religious coping, whereby caregivers described a strong faith or spirituality enabling them to cope with their caregiving responsibilities; having strong religious convictions enabled better stress management (Azman et al., 2017). Church services were a source of social support, and seeking advice from a pastor was also valued (Gerdner et al., 2007). Attending church services and upholding religious practices and values allowed caregivers to maintain a life separate from caregiving, which they considered important (Thornton and Hopp, 2011).

Use of cognitive strategies

Cognitive coping strategies were identified in six papers. These strategies involved a conscious effort to alter perceptions, appraisals or cognitions surrounding caregiving to promote a greater sense of well-being. Unlike problem- or emotion-focussed coping, cognitive strategies are not behavioural and are defined as thoughts used to deal with stressful or challenging situations which typically involve the mental perception an individual has surrounding their ability to manage a stressor (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). Most reported was the use of acceptance. This involved acceptance of inequalities surrounding caregiving and the individual being caring for, as well as accepting that the situation was unchangeable and that life could never be the same again (Azman et al., 2017; Dickson et al., 2012; McCausland Kurz and Cavanaugh, 2001; Williams et al., 2014; Zegwaard et al., 2013). Appraisal was highlighted as an important factor. Haley et al. (1996) found that the effects of stressors were mediated by the appraisal caregivers had of their experiences, and Pakenham and Bursnall (2006) reported that higher stress appraisals were related to higher distress and lower life satisfaction in caregivers.

Social comparisons were also used by caregivers, including comparing their current situation to another difficult situation in their past, such as the illness or death of parents (McCausland Kurz and Cavanaugh, 2001). In addition, caregivers reported making downward comparisons to others in similar circumstances, as well as considering themselves more fortunate and comparing their resources to others to feel efficient and capable (Williams et al., 2014).

Some cognitive strategies involved perceptions of the caregiver role, and caregivers reported that valuing their role, retaining autonomy, identifying benefits and finding meaning in their experiences helped them adjust to their situation (Kitter and Sharman, 2015; Thornton and Hopp, 2011; Zegwaard et al., 2013). Reframing aspects of their experience enabled effective coping and involved looking on the bright side; finding humour when feeling helpless and reframing perceptions positively (Bailey et al., 2013; Williams et al., 2014). In particular, taking a gain rather than a loss mentality was deemed helpful by those who chose to perceive their caregiving as a choice and voluntary act of compassion, rather than as a forced obligation (Zegwaard et al., 2013).

Factors associated with psychological adjustment

A number of factors associated with psychological adjustment were identified. Social support was frequently correlated with positive adjustment. High levels of social support correlated with higher positive outcomes, less distress and better health in caregivers (Haley et al., 1996; Pakenham and Bursnall, 2006). Wong et al. (2015) found that a strong, positive marital bond, affection and feeling cared for were supportive of good adjustment in caregivers. Consistent positive social interaction which enabled individuals to feel supported in terms of their emotions and self-esteem was also deemed important for adjustment and promoted resilience (Kaplan, 2010; McCausland Kurz and Cavanaugh, 2001; Ruiz-Robledillo et al., 2014). Specifically, caregivers noted that opportunities to share information and their experiences within their social network positively influenced their adjustment and outcomes (Kita and Ito, 2013; McCausland Kurz and Cavanaugh, 2001). Social support also took the form of practical support and was associated with adjustment (McCausland Kurz and Cavanaugh, 2001). Practical support in the form of physical care often came from friends or family members, such as adult children (Gerdner et al., 2007; Kaplan, 2010). Tangible support was also sought in a more formal manner from professional services such as adult day care or home health services, and was positively associated with adjustment (Gerdner et al., 2007).

Factors associated with poorer adjustment were identified in two studies. Bachanas et al. (2001) found that a greater number of daily hassles, use of emotion-focussed coping and fewer family resources were related to poorer adjustment. Pakenham and Bursnall (2006) established that lower levels of perceived choice in caregiving were associated with lower adjustment on measures such as life satisfaction, benefit finding and positive affect.

Factors associated with physiological adjustment

Only six studies reported findings regarding physiological adjustment, five of which measured self-reported physical health to determine health status. Two studies found that caregivers endorsed more symptoms using physical health measures and worse health than controls (Mccallum et al., 2007; Ruiz-Robledillo and Moya-Albiol, 2013). Some studies reported specific factors that are positively associated with better self-reported health in caregivers, and these included increased use of problem-solving coping and higher resilience (Figueiredo et al., 2014; Ruiz-Robledillo et al., 2014). Other studies reported factors that were negatively associated with self-reported health. Ruiz-Robledillo and Moya-Albiol (2013) found that higher trait anxiety, greater cognitive-oriented problem coping and higher levels of burden were associated with poorer health in caregivers. However, Kim and Knight (2008) found that coping was not associated with the impact of caregiving on health outcomes.

In addition to self-report measures, four papers used biomarkers of stress in the form of blood pressure and salivary cortisol. Studies assessing cortisol have generally found support for caregiving as a stressor associated with increases in cortisol levels and disruption of the diurnal decrease or awakening response. Higher cortisol and blood pressure were reported in caregivers compared to non-caregivers (Kim and Knight, 2008; Ruiz-Robledillo and Moya-Albiol, 2013). Kim and Knight (2008) reported that lower instrumental social support was associated with higher levels of salivary cortisol, and Ruiz-Robledillo et al. (2014) found that resilience was negatively correlated with caregivers’ cortisol awakening response (CAR) and also reported lower total salivary cortisol concentration, as assessed by a smaller area under the curve, over the sampling period. However, Merritt and McCallum (2013) found that greater use of positive religious coping correlated with a flatter cortisol decline across the day for African-American (AA) caregivers coping with behavioural problems in family members with dementia compared to non-caregivers, suggesting that AA caregivers require a wider range of religious coping skills that incorporates both positive and negative religious coping.

Methodological considerations

In this systematic review, a number of methodological issues were evident. Since evidence shows that caregiving can significantly impact the psychosocial and physical health of individuals, it was surprising that 23 papers assessed only psychosocial factors; most particularly, coping strategies, coping resources, social adjustment, stress appraisal and positive and negative affect. Only four studies utilised physiological measures, notably blood pressure and salivary cortisol. Eight studies used self-reported physical health and symptom inventory checklists. Reviews of method sections found a wide variety of measures were employed, approximately 60 different scales and measures. Of these, eight were caregiver-specific.

Although 15 studies referred to theory, 12 did not. Of the 13 quantitative studies, 9 referred to theory, most commonly the TSC (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984) and the Sociocultural Stress and Coping Model for Caregivers (Aranda and Knight, 1997). In some instances, these theories guided research and were tested, but in others were provided to explain findings. Of the 14 qualitative studies, 6 referenced theory, most often the ABCX Model of Family Adaptation (McCubbin and Patterson, 1983) and Stress Coping Frameworks (Knight et al., 2000; Lazarus and Folkman, 1984).

Only 2 of the 27 studies were longitudinal. The first, a quantitative study (Kim et al., 2003) provided predictive data regarding problem- and emotion-focussed coping in mothers caring for an adult child. The second, a 7-month qualitative case study (Le Dorze et al., 2009) observed adjustment of a daughter whose father had aphasia and had suffered a stroke.

Finally, much of the caregiver literature has focussed on older adults, with some investigating younger adults, very few explore coping and adjustment in young carers. Of the 27 studies, 23 reported the mean age of the caregivers; in 22 of these studies, it ranged from 25 to 74 years. Only one study reported a mean caregiver age that would be considered a young carer population; ages ranged from 10 to 25 years (mean age of 17 years).

Discussion

Through this systematic review of quantitative and qualitative literature, a number of coping factors associated with adjustment in caregivers were identified.

Summary of findings

Problem-focussed coping as a method for adjusting to the role and responsibilities of caregiving was associated with more positive adjustment and outcomes. Emotion-focussed coping was associated negatively with caregiver adjustment and linked to increased psychological and emotional distress. Despite this general finding, some subjective reports in qualitative data identified helpful emotion-focussed techniques. This highlights the dynamic and changing nature of coping, and the importance of taking into account individual circumstances. Previous research has found that strategies cannot necessarily be categorised into positive or negative approaches and that some stressors, such as those that cannot be changed by way of problem-focussed approaches, benefit most from emotion-focussed techniques (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). Unfortunately, the literature in this review does not offer information regarding the fit between the stressor and a chosen coping strategy in caregivers. This warrants investigation.

In addition to problem- and emotion-focussed strategies, a number of cognitive strategies were identified. While cognitive factors can be viewed as independent of problem- and emotion-focussed coping, it is important to acknowledge that the three strategy styles cannot always be viewed separately. The associations between different coping styles identified in this review support the findings of previous research demonstrating that a combination of problem-focussed, emotion-focussed and cognitive strategies is often the most effective way to cope with stressors (Pakenham, 2001). The studies in this review do not provide insight regarding the balance between coping approaches or the number of unique strategies employed.

Ten papers in the review identified factors associated with poor adjustment (three studies) and positive adjustment (seven studies). The factor most frequently positively correlated with adjustment was social support in the form of emotional and physical, tangible assistance. Caregivers highlighted that sharing their experiences and information with other carers was useful, confirming the protective nature of social support against social judgement and perceived stress (Beck, 2007).

Although only six of the papers reported physiological adjustment in caregivers, some common findings were identified. Overall, this review supports previous findings that caregiving is associated with elevated cortisol levels and subjective reports of poorer health compared to non-caregivers. Since the immune system naturally deteriorates with age (termed immunosenescence), the impact of stress may be greater or more pronounced in older individuals (Vedhara et al., 2002). As such, findings from adult and elderly caregivers may not represent young carers, who potentially have a more optimum immune system. The mean age of participants in the six studies reporting physical health outcomes was 55.5 years. The caregiver literature would benefit from further research surrounding physiological outcomes across all age groups to adequately disaggregate the physiological effects on immune functioning by age. It is evident from this review that it is important to extend research using physiological markers, such as salivary cortisol, to young caregivers. To our knowledge, this has not yet been conducted and could provide an indication of the effects of caregiving across the lifespan. This is supported by Barnett and Parker’s (1998) assertion that although a great deal of research has been conducted with adult caregivers, the same cannot be said for young caregivers. In particular, Simon and Slatcher (2011) note that little is known about the physical health of child caregivers compared to adults. This review highlights this limitation.

Methodological considerations and limitations of the review literature

Numerous methodological considerations regarding the studies in this review were identified. During data extraction, it was evident that a variety of quantitative measures were employed to assess aspects of caregiving; there were very few designed specifically for caregivers. An important question to address is whether tailor-made measures for caregivers would be useful to assess factors such as burden and stress in this unique population. Furthermore, a more consistent use of measures across studies would increase their comparative value and enable meta-analyses to be conducted.

Regarding outcome measures, only six studies took a biopsychosocial approach, measuring physical health through either self-report or physiological measurement. The remaining 21 studies measured purely psychosocial factors and did not consider physical outcomes. Assessment of physiological outcomes in the adjustment of caregivers however, is gaining interest, as shown by the more recent studies reviewed; we would call for such assessments receiving greater attention.

There is limited focus on young carers, with only one study investigating this population. The most recent UK census reported 177,918 young carers between 5 and 17 years old; however, this is believed to be a gross underrepresentation. Although research has identified the potential negative impact of early caregiving (Thomas et al., 2003), not all young carers or children living with ill parents demonstrate these outcomes. In fact, some show evidence of resilience, particularly physiologically (Turner-Cobb et al., 1998). It is imperative that future research investigates this population to determine resilience factors. The TSC (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984), which many studies refer to, describes a dynamic process, capable of changing and developing over time. Exposure to caregiving at a young age may impact adulthood and longitudinal study of caregivers at various points in their life would allow the process of coping to be observed over time and investigation of the temporal demands of caregiving.

A call for greater longitudinal research in caregiver coping is further supported by the majority of quantitative studies in this review being of cross-sectional design and offering little predictive value to assess the direct impact of specific coping strategies on adjustment. While cross-sectional studies have provided insight in this relatively new field, progression towards longitudinal assessment with the power to predict the effect of coping strategies upon adjustment is needed.

Strengths of the review literature

Despite the numerous limitations noted within the papers, there are strengths. First, all studies, when subjected to quality appraisal, were deemed sufficient in quality to be included in the study, suggesting research in this area is being conducted rigorously. Second, although some studies reported the negative impact of caregiving and factors associated with poor adjustment, many studies took a resiliency approach, focusing on coping factors positively associated with adjustment. Future development of interventions designed to help caregivers cope effectively can be enhanced by inclusion of such factors.

Limitations of the review

This systematic review has limitations. First, due to language barriers, papers not written in English were excluded. Despite this, the included studies were carried out in a range of countries, including the United Kingdom, United States, Portugal and Korea (Bachanas et al., 2001; Barbosa et al., 2011; Dickson et al., 2012; Kim and Knight, 2008), reducing the likelihood of cultural bias. Second, only published papers were included, this was to ensure a level of quality subject to peer-review. As such, it is possible that we introduced a bias by not representing studies with unexpected or non-significant findings. However, the inclusion of qualitative literature, with sufficient quality ratings, that do not require statistical analysis or significance ensures a variety of findings were reported. Furthermore, this review used the terms ‘carer’ and ‘caregiver’ when searching, which poses a possible issue as these terms are relatively new in the literature. Early work used descriptive terms (e.g. spouses of individuals with an illness or children living with parental illness) rather than identifying individuals as caregivers per se (Folkman et al., 1997; Westbom, 1992). It is possible that use of these terms resulted in the exclusion of relevant literature. Finally, though the term adjustment was chosen for use in this review due to its encompassing nature with regard to outcomes and coping, it is possible that not deconstructing this term and focusing on specific aspects of adjustment may also have limited the literature found when searching.

Conclusion

This study reviewed the literature surrounding coping and adjustment in caregivers across all ages, to identify outcomes associated with caregiving and to contribute to this developing area of research by identifying coping factors associated with adjustment.

This review found that problem-focussed coping is associated with more positive adjustment than emotion-focussed coping. Cognitive strategies (e.g. acceptance and appraisal) were positively related to adjustment, as well as social support, particularly with regard to physiological outcomes. Given these findings, those seeking to provide caregiver support may consider harnessing these factors, for example, developing coping skills and social support networks.

Methodological issues were identified, which highlight considerable gaps within the literature and present a strong call for research that seeks to (1) address the imbalance between studies using purely psychosocial measures and the few using physiological measures to develop a deeper understanding regarding the physiological impact of caregiving; (2) develop longitudinal studies to provide predictive data and (3) investigate young carers to assess the impact of caregiving across the lifespan. Beyond this review, further meta-analytic examination of findings in this field is warranted and called for.

To develop appropriate interventions for a growing caregiver population, a clear and coherent understanding of the mechanisms underlying coping, adjustment, vulnerability and resilience in operation is needed. This systematic review highlights the importance of such work and draws attention to the gaps in caregiver research across different age groups, as well as the need for a more coherent understanding of consistencies and discrepancies in caregiver outcomes at different points across the lifespan.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, PRISMA for Coping and adjustment in caregivers: A systematic review by Tamsyn Hawken, Julie Turner-Cobb and Julie Barnett in Health Psychology Open

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Table_1-2_Main_characteristics_of_included_studies for Coping and adjustment in caregivers: A systematic review by Tamsyn Hawken, Julie Turner-Cobb and Julie Barnett in Health Psychology Open

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by an Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) Studentship.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material is available for this article online.

References

*Included as one of the 27 papers in the systematic review reported.

- Aranda MPM, Knight BBG. (1997) The influence of ethnicity and culture on the caregiver stress and coping process: A sociocultural review and analysis. The Gerontologist 37(3): 342–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Azman A, Jamir Singh PS, Sulaiman J. (2017) Caregiver coping with the mentally ill: A qualitative study. Journal of Mental Health 26(2): 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Bachanas PJ, Kullgren KA, Schwartz KS, et al. (2001) Psychological adjustment in caregivers of school-age children infected with HIV: Stress, coping, and family factors. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 26(6): 331–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Bailey SJ, Letiecq BL, Erickson M, et al. (2013) Resilient grandparent caregivers: Pathways to positive adaptation. In: Hayslip B, Smith GC. (eds) Resilient Grandparent Caregivers: A Strengths-based Perspective. New York: Routledge, pp. 70–87. [Google Scholar]

- *Barbosa A, Figueiredo D, Sousa L, et al. (2011) Coping with the caregiving role: Differences between primary and secondary caregivers of dependent elderly people. Aging and Mental Health 15(4): 490–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett B, Parker G. (1998) The parentified child: Early competence or childhood deprivation? Child Psychology and Psychiatry Review 3(4): 146–155. [Google Scholar]

- Beck L. (2007) Social status, social support, and stress: A comparative review of the health consequences of social control factors. Health Psychology Review 1: 186–207. [Google Scholar]

- Becker S, Dearden C, Aldridge J, et al. (2000) Young carers in the UK: Research, policy and practice. Research, Policy and Planning 8(2): 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Branscum AY. (2011) Stress and coping model for family caregivers of older adults. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences 71(9–A): 3378. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. (1989) Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 56(2): 267–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cass B, Smyth C, Hill T, et al. (2009) Young carers in Australia: Understanding the advantages and disadvantages of their care giving. Social Policy Research Paper No. 38. Available at: https://www.sprc.unsw.edu.au/media/SPRCFile/26_Social_Policy_Research_Paper_38.pdf

- Cohen CA, Colantonio A, Vernich L. (2002) Positive aspects of caregiving: Rounding out the caregiver experience. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 17(2): 184–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del-Pino-Casado R, Frías-Osuna A, Palomino-Moral PA, et al. (2011) Coping and subjective burden in caregivers of older relatives: A quantitative systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing 67: 2311–2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Dickson A, O’Brien G, Ward R, et al. (2012) Adjustment and coping in spousal caregivers following a traumatic spinal cord injury: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Journal of Health Psychology 17(2): 247–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge MD, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. (2016) Caregiver stress and possible solutions. In: Scharre DW. (ed.) Long-Term Management of Dementia. New York: Taylor and Francis, pp. 225. [Google Scholar]

- *Figueiredo D, Gabriel R, Jácome C, et al. (2014) Caring for people with early and advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: How do family carers cope? Journal of Clinical Nursing 23(1–2): 211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Moskowitz JT, Ozer EM, et al. (1997) Positive meaningful events and coping in the context of HIV/AIDS. In: Gottlieb BH. (ed.) Coping with Chronic Stress. Boston, MA: Springer, pp. 293–314. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher S, Phillips AC, Drayson MT, et al. (2009) Parental caregivers of children with developmental disabilities mount a poor antibody response to pneumococcal vaccination. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 23(3): 338–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garity J. (1997) Stress, learning style, resilience factors, and ways of coping in Alzheimer family caregivers. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 12(4): 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- *Gerdner LA, Tripp-Reimer T, Simpson HC. (2007) Hard lives, god’s help, and struggling through: Caregiving in Arkansas delta. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology 22(4): 355–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley WE, Levine EG, Brown SL, et al. (1987) Stress, appraisal, coping, and social support as predictors of adaptational outcome among dementia caregivers. Psychology and Aging 2(4): 323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Haley WE, Roth DL, Coleton MI, et al. (1996) Appraisal, coping, and social support as mediators of well-being in Black and White family caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64(1): 121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kaplan RL. (2010) Caregiving mothers of children with impairments: Coping and support in Russia. Disability and Society 25(6): 715–729. [Google Scholar]

- *Kim HW, Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM, et al. (2003) The role of coping in maintaining the psychological well-being of mothers of adults with intellectual disability and mental illness. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 47(4–5): 313–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kim JH, Knight BG. (2008) Effects of caregiver status, coping styles, and social support on the physical health of Korean American caregivers. Gerontologist 48(3): 287–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kita M, Ito K. (2013) The caregiving process of the family unit caring for a frail older family member at home: A grounded theory study. International Journal of Older People Nursing 8(2): 149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kitter B, Sharman R. (2015) Caregivers’ support needs and factors promoting resiliency after brain injury. Brain Injury 29(9): 1082–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kmet LM, Lee RC, Cook LS. (2004) Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research from a Variety of Fields. AHFMR – HTA Initiative #13, February. Edmonton, AB, Canada: Alberta Heritage Foundaalberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR), pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Knight BG, Silverstein M, McCallum TJ, et al. (2000) A sociocultural stress and coping model for mental health outcomes among African American caregivers in Southern California. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 55(3): P142–P150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laisné F, Lecomte C, Corbière M. (2012) Biopsychosocial predictors of prognosis in musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic review of the literature (corrected and republished). Disability and Rehabilitation 34(22): 1912–1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen PD, Lubkin IM. (2009) Chronic Illness: Impact and Intervention (Jones and Bartlett Series in Oncology). Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. (1984) Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- *Le Dorze G, Tremblay V, Croteau C. (2009) A qualitative longitudinal case study of a daughter’s adaptation process to her father’s aphasia and stroke. Aphasiology 23(4): 483–502. [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Loke AY. (2013) The positive aspects of caregiving for cancer patients: A critical review of the literature and directions for future research. Psycho-Oncology 22(11): 2399–2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell B, Moss M, Wetherell M. (2012) The psychosocial, endocrine and immune consequences of caring for a child with autism or ADHD. Psychoneuroendocrinology 37(4): 534–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low JTS, Payne S, Roderick P. (1999) The impact of stroke on informal carers: A literature review. Social Science and Medicine 49: 711–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *McCallum TJ, Longmire CF, Knight BG. (2007) African American and white female caregivers and the sociocultural stress and coping model. Clinical Gerontologist 30(4): 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- *McCausland Kurz J, Cavanaugh JC. (2001) A qualitative study of stress and coping strategies used by well spouses of lung transplant candidates. Families, Systems, & Health 19(2): 181–197. [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin HI, Patterson JM. (1983) The family stress process: The double ABCX model of adjustment and adaptation. Social Stress and the Family: Advances and Developments in Family Stress Theory and Research 6(1–2): 7–37. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. (1998) Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 840: 33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews BL. (2018) Life of the second-order patient: Factors impacting the informal caregiver. Journal of Loss and Trauma 23(1): 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- *Mausbach BT, Chattillion EA, Roepke SK, et al. (2013) A comparison of psychosocial outcomes in elderly Alzheimer caregivers and noncaregivers. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 21(1): 5–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Merritt MM, McCallum TJ. (2013) Too much of a good thing? Positive religious coping predicts worse diurnal salivary cortisol patterns for overwhelmed African American female dementia family caregivers. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 21(1): 46–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. (2010) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement… Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. British Medical Journal 8: b2535. [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics (2012) Providing unpaid care may have an adverse effect on young carers’ general health. Available at: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/census/2011-census-analysis/provision-of-unpaid-care-in-england-and-wales-2011/styunpaidcare.html (accessed 1 April 2016).

- Pakenham KI. (2001) Application of a stress and coping model to caregiving in multiple sclerosis. Psychology, Health & Medicine 6(1): 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- *Pakenham KI, Bursnall S. (2006) Relations between social support, appraisal and coping and both positive and negative outcomes for children of a parent with multiple sclerosis and comparisons with children of healthy parents. Clinical Rehabilitation 20(8): 709–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakenham KI, Bursnall S, Chiu J, et al. (2006) The psychosocial impact of caregiving on young people who have a parent with an illness or disability: Comparisons between young caregivers and noncaregivers. Rehabilitation Psychology 51(2): 113–126. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. (2003) Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging 18(2): 250–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruessner JC, Hellhammer DH, Kirschbaum C. (1999) Burnout, perceived stress, and cortisol responses to awakening. Psychosomatic Medicine 61(2): 197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revenson T, Griva K, Luszczynska A, et al. (2016) Caregiving in the Illness Context. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- *Ruiz-Robledillo N, Moya-Albiol L. (2013) Self-reported health and cortisol awakening response in parents of people with asperger syndrome: The role of trait anger and anxiety, coping and burden. Psychology and Health 28(11): 1246–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Ruiz-Robledillo N, De Andrés-García S, Pérez-Blasco J, et al. (2014) Highly resilient coping entails better perceived health, high social support and low morning cortisol levels in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities 35(3): 686–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Sander AM, High WM, Hannay HJ, et al. (1997) Predictors of psychological health in caregivers of patients with closed head injury. Brain Injury 11(4): 235–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandstedt P, Littorin S, Cröde Widsell G, et al. (2018) Caregiver experience, health-related quality of life and life satisfaction among informal caregivers to patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Clinical Nursing. Epub ahead of print 2 July. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.14593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawatzky JE, Fowler-Kerry S. (2003) Impact of caregiving: Listening to the voice of informal caregivers. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 10(3): 277–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubart JR. (2014) Caring for the family caregiver. In: Mostofsky (ed.) The Handbook of Behavioral Medicine. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 913–930. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R, Schwarzer C. (1996) A critical survey of coping instruments. In: Zeidner M, Endler NS. (eds) Handbook of Coping: Theory, Research, Applications. New York: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 107–132. [Google Scholar]

- Simon C, Slatcher C. (2011) Young carers. Innovait: The RCGP Journal for Associates in Training 4(8): 458–463. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA. (2007) Coping assessment. In: Cambridge Handbook of Psychology, Health and Medicine (2nd edn), pp. 245–250. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling P, Eyer J. (1988) Allostasis: A new paradigm to explain arousal pathology. In: Ayers S, Baum A, McManus C, et al. (eds) Handbook of Life Stress, Cognition and Health. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 629–639. [Google Scholar]

- *Sun F. (2014) Caregiving stress and coping: A thematic analysis of Chinese family caregivers of persons with dementia. Dementia 13(6): 803–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas N, Stainton T, Jackson S, et al. (2003) ‘Your friends don’t understand’: Invisibility and unmet need: In the lives of ‘young carers’. Child and Family Social Work 8(1): 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- *Thornton N, Hopp FP. (2011) ‘So I just took over’: African American daughters’ caregiving for parents with heart failure. Families in Society 92(2): 211–217. [Google Scholar]

- Turner-Cobb SMT, Steptoe A, Perry L, et al. (1998) Adjustment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and their children. Journal of Rheumatology 25(3): 565–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedhara K, Cox NK, Wilcock GK, et al. (1999) Chronic stress in elderly carers of dementia patients and antibody response to influenza vaccination. The Lancet 353(9153): 627–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedhara K, McDermott MP, Evans TG, et al. (2002) Chronic stress in nonelderly caregivers: Psychological, endocrine and immune implications. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 53(6): 1153–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westbom L. (1992) Impact of chronic illness in children on parental living conditions: A population-based study in a Swedish primary care district. Scand J Prim Health Care 10(2): 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Williams KL, Morrison V, Robinson CA. (2014) Exploring caregiving experiences: Caregiver coping and making sense of illness. Aging and Mental Health 18(5): 600–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Wong OL, Kwong PS, Ho CKY, et al. (2015) Living with dementia: An exploratory study of caregiving in a Chinese family context. Social Work in Health Care 54(8): 758–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Zegwaard MI, Aartsen MJ, Grypdonck MH, et al. (2013) Differences in impact of long term caregiving for mentally ill older adults on the daily life of informal caregivers: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry 13(1): 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, PRISMA for Coping and adjustment in caregivers: A systematic review by Tamsyn Hawken, Julie Turner-Cobb and Julie Barnett in Health Psychology Open

Supplemental material, Table_1-2_Main_characteristics_of_included_studies for Coping and adjustment in caregivers: A systematic review by Tamsyn Hawken, Julie Turner-Cobb and Julie Barnett in Health Psychology Open