Abstract

Background:

Projecting the demand for plastic surgeons has become increasingly important in a climate of scarce public resource within a single payer health-care system. The goal of this study is to provide a comprehensive workforce update and describe the perceptions of the workforce among Canadian Plastic Surgery residents and surgeons.

Methods:

Two questionnaires were developed by a national task force under the Canadian Plastic Surgery Research Collaborative. The surveys were distributed to residents and practicing surgeons, respectively.

Results:

Two-hundred fifteen (49%) surgeons responded, with a mean age of 51.4 years (standard deviation [SD] = 11.5); 78% were male. Thirty-three percent had been in practice for 25 years or longer. More than half of respondents were practicing in a large urban center. Fifty-nine percent believed their group was going to hire in the next 2 to 3 years; however, only 36% believed their health authority/provincial government had the necessary resources. The mean desired age of retirement was 67 years (SD = 6.4). We predict the surgeons-to-population ratio to be 1.55:100 000 and the graduate-to-retiree ratio to be 2.16:1 within the next 5 to 10 years. Seventy-seven (49%) residents responded. Most were “very satisfied” with their training (61%) and operative experience (90%). Eighty-nine percent of respondents planned to pursue addqitional training after residency, with 70% stating that the current job market was contributing to their decision. Most residents responded that they were concerned with the current job market.

Conclusions:

The results of this study predict an adequate number of plastic surgeons will be trained within the next 10 years to suit the population’s requirements; however, there is concern that newly trained surgeons will not have access to the necessary resources to meet growing demands. Furthermore, there is an evident shortage of those practicing in rural areas. Many trainees worry about the availability of jobs, despite evidence of active recruitment. The workforce may benefit from structured career mentorship in residency and improved transparency in hiring practices, particularly to attract young surgeons to smaller communities. It may also benefit from a coordinated national approach to recruitment and succession planning.

Keywords: employment, health manpower, plastic surgery, residency training

Abstract

Historique:

Il est de plus en plus important de projeter la demande de plasticiens compte tenu des ressources publiques rares dans un système de santé à un seul payeur. La présente étude vise à présenter une mise à jour complète des effectifs et à décrire les perceptions de la main-d’œuvre chez les résidents et les chirurgiens canadiens en chirurgie plastique.

Méthodologie:

Un groupe de travail national relevant du Canadian Plastic Surgery Research Collaborative a créé deux questionnaires, qui ont été distribués respectivement aux résidents et aux chirurgiens en exercice.

Résultats:

Deux cent quinze chirurgiens (49 %), d’un âge moyen de 51,4 ans (ÉT = 11,5) ont répondu; 78 % étaient de sexe masculin. Trente-trois pour cent exerçaient depuis au moins 25 ans. Plus de la moitié exerçait dans un grand centre urbain. Cinquante-neuf pour cent pensaient que leur groupe embaucherait dans les deux à trois années suivantes, mais seulement 36 % étaient d’avis que leur autorité sanitaire ou leur gouvernement provincial possédait les ressources nécessaires. En moyenne, les répondants souhaitaient prendre leur retraite à 67 ans (ÉT = 6,4). Les chercheurs prédisent que le ratio entre les chirurgiens et la population serait de 1,55:100 000, et que le ratio entre les diplômés et les retraités serait de 2,16:1 d’ici cinq à dix ans. Soixante-dix-sept résidents (49 %) ont répondu. La plupart étaient « très satisfaits » de leur formation (61 %) et de leur expérience opératoire (90 %). Quatre-vingt-neuf pour cent planifiaient poursuivre leur formation après la résidence, et 70 % affirmaient que le marché du travail actuel contribuait à leur décision. La plupart des résidents ont répondu qu’ils étaient inquiets du marché du travail actuel.

Conclusions:

Selon les résultats de cette étude, un nombre suffisant de plasticiens seront formés d’ici dix ans pour répondre aux besoins de la population, mais on craint que les chirurgiens nouvellement formés n’aient pas accès aux ressources nécessaires pour répondre à la demande croissante. De plus, on constate une pénurie évidente en région rurale. De nombreux résidents s’inquiètent de la disponibilité des emplois malgré des preuves de recrutement actif. La main-d’œuvre pourrait profiter d’un mentorat professionnel structuré en résidence et d’une plus grande transparence des pratiques d’embauche, particulièrement pour attirer de jeunes chirurgiens dans de plus petites localités. Elle pourrait également profiter d’une approche nationale coordonnée du recrutement et de la planification de la succession.

Background

Projecting the demand for physicians has become increasingly important in a climate of scarce public health-care resources. Despite significant increases in health-care expenditure, Canada’s outcomes fall short when compared to other developed nations.1 In fact, Canada ranks only 30th in overall health-care performance,2 which is thought, in part, to be the result of limited human resources.3 In response, policy makers have increased the number of physicians and surgeons in Canada in an attempt to relieve the burden of overworked physicians and crowded emergency rooms.4,5 Whether such changes have made any significant difference remains an area of ongoing debate.6 However, public outcry to improve the availability of insured services remains.7-9

Medical and surgical residents, who will comprise the next workforce cohort, are also principal stakeholders in the analytics of physician supply and demand. In recent years, there are a number of surgical specialties that have suffered from a crisis of unemployment.10-13 Although advanced data detailing physician need have allowed medical students, residents, and training programs to make informed decisions, a disconnect remains between the number of physicians being trained and the existing demand.14 This is further complicated by the paucity of workforce data.

Anticipating the need for, and supply of, physicians is complex. The ideal ratio of surgeons-per-population is highly dependent on the burden of disease, the expected population growth, and the region of interest. For plastic surgery, in the United States, crude estimates range from 1.1 to 2.22 surgeons per 100 000 population.15 In Canada, a target of 1.3 surgeons per 100 000 has been set.16 The absence of data on the private practice sector in plastic surgery further complicates workforce assessments. Moreover, relative to other surgical specialties, estimates of need for plastic surgeons remain low. This is exemplified by data in the general surgery17 and otolaryngology18 literature, where accepted ratios range from 7.1 to 7.53 and 2.69 to 3.77 per 100 000, respectively.

Recent US workforce assessments forecasted a shortage of plastic surgeons, citing a rapidly growing population, increasing competition from other services, and the growing demand for aesthetic surgery.19,20 Similarly, the most recent Canadian surgical workforce study advocated for increasing the number of trainees and offering incentives for graduates to stay in Canada. These authors highlighted the burden of overworked surgeons, long wait times, and underserviced rural communities.16

To our knowledge, more than a decade has passed since the last Canadian Plastic Surgery workforce assessment.16 The purpose of this study is to determine whether there will be an adequate numbers of plastic surgeons in Canada. Additionally, this study aimed to develop a better understanding of the current perceptions of the workforce among plastic surgeons and plastic surgery residents.

Methods

This study was conducted by the Canadian Plastic Surgery Research Collaborative, a national trainee-led network and organization dedicated to conducting high-quality multicenter research in plastic surgery.21

Survey Development

Two surveys were developed for the purpose of this study. The first survey (Part I) was distributed to Canadian Plastic Surgeons who are members of the Canadian Society of Plastic Surgery (CSPS). The second survey (part II) was distributed to Canadian Plastic Surgery residents.

The mixed methodology surveys were developed de novo from an extensive literature review and following discussion with medical students, plastic surgery residents, and 2 staff surgeons (D. T. T., and J. A.). Part I was developed using previous workforce assessments as a template to allow for analysis of trends over 10 years.16,19 Both surveys went through a series of revisions by all contributors as well as our research ethics board. It was piloted locally to assess clarity and revised based on feedback.

Part I consisted of 39 items including 8 Likert-scale questions, 17 close-ended questions, and 4 open-ended questions. Questions included the following domains: demographics, practice characteristics, and future practice plans (eg, migration, retirement, and so on). Part II consisted of 32 items including 10 Likert-scale questions, 19 close-ended questions, and 3 open-ended questions. Questions included the following domains: demographics, training characteristics, perceptions of the current workforce, and preparedness to enter practice.

Survey Distribution

Research Ethics Board (Nova Scotia Health Authority File No. 1021669) approval was obtained prior to survey dissemination.

Part I was distributed to all members of the CSPS (n = 438) via e-mail in October 2016. (Note: Not all practicing Canadian Plastic Surgeons are members of the CSPS22). One additional e-mail reminder was sent (November 27, 2016).

Part II was distributed to plastic surgery residents via the Canadian Plastic Surgery Research Collaborative through local site representatives in each of the 13 academic centers across Canada. One additional e-mail reminder was sent (November 26, 2016).

Responses were collected electronically for a period of approximately 3 months for Part I and 4 months for Part II using the Opinio Software System (ObjectPlant, Inc, Oslo, Norway).

Analysis

Statistical analysis was done in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington). Qualitative data were itemized and thematically analyzed by 2 independent analysts (B.A. and A.M.) to identify common themes in responses to open-ended questions. Using MatLab (Mathworks, Natick, Massachusetts), postal codes provided by respondents were converted to geographic coordinates and plotted.

Results

Part I

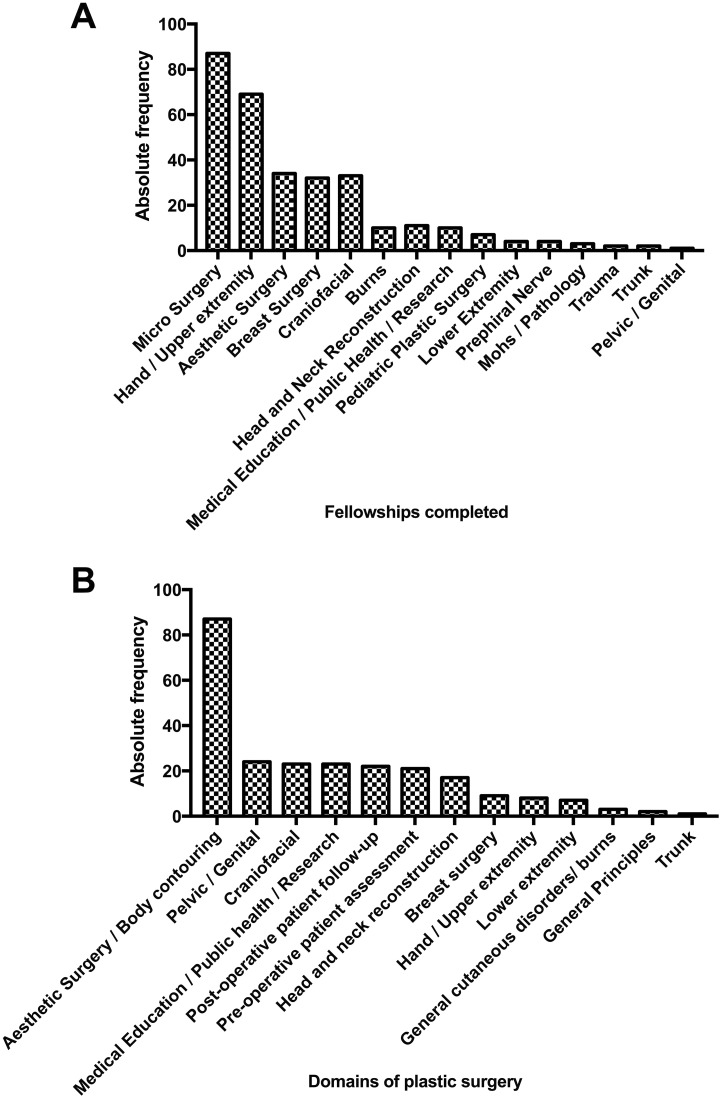

A total of 215 (215 of 438, 49%) Canadian plastic surgeons responded. The majority of respondents were male (167 of 215, 78%), between the ages of 40 and 49 years (70 of 215, 33%). The vast majority of surgeons completed their medical school (205 of 215, 95%) and residency training (203 of 215, 94%) in Canada. The average number of fellowships completed was 1.6 (range = 0-4; Table 1). Fellowship type is summarized in Figure 1A. Aesthetic surgery was the most commonly identified deficiency in the first 5 years of practice (Figure 1B). Geographic distribution of the respondents is illustrated in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participating Licensed Plastic Surgeons in Canada.a

| Characteristics | Frequencyb | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Overall | 215 | 100 |

| Age | ||

| 20-29 | 1 | 0.50 |

| 30-39 | 38 | 17.7 |

| 40-49 | 70 | 32.6 |

| 50-59 | 48 | 22.3 |

| 60-69 | 52 | 24.2 |

| 70-79 | 5 | 2.30 |

| 80-89 | 1 | 0.50 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 167 | 77.7 |

| Female | 48 | 22.3 |

| Medical school | ||

| Canada | 205 | 95.3 |

| United States | 3 | 1.40 |

| United Kingdom | 2 | 0.90 |

| Europe | 3 | 1.40 |

| South Africa | 1 | 0.50 |

| Middle East | 1 | 0.50 |

| Residency program | ||

| Canada | 203 | 94.4 |

| United States | 9 | 4.20 |

| Europe | 2 | 0.90 |

| South Africa | 1 | 0.50 |

| Perceived preparedness, M (IQR)c | 4 | 4-5 |

| Fellowships | 172 | 80.4 |

| None | 42 | 19.6 |

| Average number, µ (STD) | 1.56 | 0.757 |

| Canada | 92 | 53.49 |

| United States | 79 | 45.93 |

| United Kingdom | 6 | 3.49 |

| Europe | 12 | 6.98 |

| Australia | 14 | 8.14 |

| Taiwan | 3 | 1.74 |

| Mexico | 3 | 1.74 |

| Japan | 3 | 1.74 |

| New Zealand | 2 | 1.16 |

| South Africa | 1 | 0.58 |

Abbreviations: M, mode; IQR, interquartile range; STD, Standard deviation.

an = 215.

bPercentages may not add up to a 100% due to missing data.

cInterquartile range (1 = very poorly prepared, 5 = very well prepared).

Figure 1.

A, Fellowships completed by practicing plastic surgeons. B, Deficiencies identified by plastic surgeons in the first 5 years of practice.

Figure 2.

Geographic distribution of Canadian plastic surgeon respondents (n = 151). All points may not be visible as coordinates overlap.

Practice Characteristics

The majority of respondents reported that they worked in either a medium or a large community practice (59 of 203, 29%) or academic practice (59 of 203, 29%). Half practiced in a city with a population greater than 1 million people (90 of 190, 47%). Fee-for-service was the most common reimbursement mechanism (153 of 191, 80%; Table 2).

Table 2.

Practice Characteristics of Participating Licensed Plastic Surgeons in Canada.a

| Practice Characteristics | Frequencyb | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Overall | 215 | 100 |

| Current practice | 203 | 92.7 |

| Private aesthetic practice | 19 | 9.40 |

| Mixed private aesthetic and academic practice | 48 | 23.6 |

| Small community practice | 11 | 5.40 |

| Medium or large community practice | 59 | 29.1 |

| Academic practice | 59 | 29.1 |

| Private aesthetic and community practice | 5 | 2.5 |

| Retiring | 1 | 0.50 |

| Aesthetics, academics, and military practice | 1 | 0.50 |

| Population of practice region | 190 | 86.8 |

| Rural | 3 | 1.60 |

| Small city/ town (100 000 or less) | 7 | 3.70 |

| City (100 001 to 249 999) | 25 | 13.2 |

| City (250,000 to 499,999) | 30 | 15.8 |

| City (500 000 to 1 000 000) | 35 | 18.4 |

| City (1 000 001 or greater) | 90 | 47.4 |

| Perceptions on workforcec | ||

| Plans to hire PS within 2-3 years | 112 | 58.9 |

| Hospital/government has resources for a new PS | 36 | 18.3 |

| PS in my region are sufficient, M (IQR) | 4 | 2.5-5 |

| Training more PS in Canada, M (IQR) | 3 | 2-3 |

| Accepting Foreign trained PS in Canada, M (IQR) | 1 | 1-3 |

| Reimbursement Mechanism | 191 | 87.2 |

| Fee-for-service | 153 | 80.1 |

| Salary (+ Academics) | 6 | 3.10 |

| Alternative funding plan | 7 | 3.70 |

| Mixed schedule | 23 | 12.0 |

| Private + Fee-for-service | 2 | 1.00 |

| Practice is completely aesthetic | 7 | 3.20 |

| Practice is completely nonaesthetic | 37 | 16.9 |

| Income is completely aesthetic | 8 | 3.70 |

| Income is completely nonaesthetic | 40 | 18.3 |

| Performs flaps | 77 | 35.2 |

Abbreviations: M, Mode; IQR, interquartile range; PS, Plastic Surgeons.

an = 215.

bPercentages may not add up to a 100% due to missing data.

cInterquartile range (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

The majority of responding surgeons had been in practice for <25 years (128 of 191, 67%). Mean number of hours worked per week, calculated from cumulative frequency data was 60.6 (SD = 18.8). Although the frequency of on-call coverage varied, most reported a regularity of 1 in 7 (43 of 171, 25%; Table 3).

Table 3.

Work Hour Characteristics of Participating Licensed Plastic Surgeons in Canada.a

| Practice Characteristics | Frequency b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||||

| Overall | 215 | 100 | |||

| Years in practice | 191 | 87.2 | |||

| Less than 5 years | 23 | 12.0 | |||

| 5 to 9 years | 33 | 17.3 | |||

| 10 to 14 years | 27 | 14.1 | |||

| 15 to 19 years | 29 | 15.2 | |||

| 20 to 24 years | 16 | 8.40 | |||

| 25 years or greater | 63 | 33.0 | |||

| Total working hours per week: | 190 | 86.8 | |||

| <10 | 2 | 1.10 | |||

| 10-19 | Details | µ (hours) | STD | 2 | 1.10 |

| 20-29 | OR | 9.50 | 10.378 | 8 | 4.20 |

| 30-39 | Private | 13.22 | 6.249 | 8 | 4.20 |

| 40-49 | Clinic | 10.77 | 5.363 | 25 | 13.2 |

| 50-59 | Minor | 6.98 | 4.186 | 53 | 27.9 |

| 60-69 | Teaching | 5.43 | 6.884 | 41 | 21.6 |

| 70-79 | Administration | 5.87 | 4.869 | 22 | 11.6 |

| 80-89 | Research | 5.37 | 7.913 | 16 | 8.40 |

| 90-99 | Calls | 33.76 | 29.766 | 9 | 4.70 |

| 100+ | 4 | 2.10 | |||

| Frequency of calls | 171 | 78.1 | |||

| 1:01 | 10 | 5.80 | |||

| 1:02 | 7 | 4.10 | |||

| 1:03 | 23 | 13.5 | |||

| 1:04 | 40 | 23.4 | |||

| 1:05 | 26 | 15.2 | |||

| 1:06 | 22 | 12.9 | |||

| 1:07 | 43 | 25.1 | |||

| Perceptions on career and plansc | |||||

| Would recommend PS to medical students | 152 | 69.4 | |||

| Overall Job Satisfaction–M (IQR)d | 4 | 4-5 | |||

| Content with current compensation–M (IQR)e | 4 | 2-4 | |||

| Likelihood to relocate practice (10-15 years)–M (IQR)f | 1 | 1-2 | |||

| Likelihood to relocate to the United States (10-15 years)–M (IQR)f | 1 | 1-2 | |||

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; OR, odds ratio; STD, Standard deviation; PS, Plastic Surgeons.

a(n = 215).

bPercentages may not add up to a 100% due to missing data.

cM, mode.

d1 = very dissatisfied, 5 = very satisfied.

e1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree.

f1 = very unlikely, 5 = very likely.

Services provided and time spent performing insured and noninsured services are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A, Percentage composition of practice by time as indicated by plastic surgeons. B, Percentage composition of practice by income as indicated by plastic surgeons. C, Aesthetic services provided by Canadian plastic surgeons.

Perception on Workforce

The majority of surgeons reported that their center was planning to hire another plastic surgeon within the next 2 to 3 years (112 of 190, 59%). When asked whether they believed their hospital/ government had the resources for a new plastic surgeon, only 36% responded in the affirmative.

Surgeons were subsequently asked a series of Likert-scale questions, from 1 to 5, where 1 indicated “strongly disagree” and 5 indicated “strongly agree.” When asked whether there were a sufficient number of plastic surgeons in their region, most agreed (mode = 4; interquartile range [IQR] = 2.5-5). When asked whether more plastic surgeons should be trained in Canada, most responded neutrally (mode = 3; IQR = 2-3). Surgeons strongly disagreed (mode = 1; IQR = 1-3) when asked whether Canada should accept more foreign-trained plastic surgeons (Table 2).

Career Satisfaction and Future Plans

The majority of surgeons would recommend plastic surgery to medical students (152 of 219, 69%), and overall job satisfaction was high (mode = 4, IQR = 4-5; 1 indicating very unsatisfied, 5 indicating very satisfied).

Workforce Projections

Using mean and standard deviation estimates of cumulative data, the age of the current plastic surgery workforce was 51.1 years (SD = 11.4), with mean planned retirement age of 67 years (SD = 6.4; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Planned age of reduction in practice volumes and retirement as indicated by practicing plastic surgeons.

We estimated an average retirement rate of 27% over the next 5 to 10 years by determining the most frequently reported desired age of retirement (60-69 years), and the number of surgeons reporting their age was 60 years or greater (n = 58).

Given a reported emigration rate of 3% (13% of respondents stated they were either “likely” or “very likely” to relocate their practice to the United States over the next 10 to 15 years), 255 expected graduates over the next 10 years, and a population growth to 36 191 000 over the next 10 years, the expected ratio of plastic surgeons per Canadian population was estimated at approximately 1.55:100 000 (Table 4). The expected graduate-to-retiree ratio is estimated to be 2.16.

Table 4.

Predicting Changes in the Plastic Surgery Workforce Over the Next 5 to 10 Years.

| Factor | Rate | Absolute Number |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 workforce | 438 | |

| Retirement | 27% | −118 |

| Emigrationa | 3% per decade | −13 |

| No. of graduates over next 10 yearsb | 25.5 per year | +255 graduates |

| Graduate/ retiree ratio | 2.16 | 255/118 |

| Total surgeons remaining | 562 | |

| Canadian population in 2026c | 36 191 000 | |

| Number of plastic surgeons/Canadian population in 2026 | 1:64 397 = 1.55:100 000 |

a3% of respondents stated they were either “likely” or “very likely” to relocate their practice to the United States over the next 10-15 years.

bFigure based on the quota of Canadian plastic surgery programs from 2007-2016.

cStatistics Canada.

Part II

Seventy-seven (49%) plastic surgery residents, from all postgraduate years, responded. There was representation from 11 (85%) of 13 major Canadian training programs. The majority of trainees were male (42 of 76, 55%). There were an equal number of married and single residents (38 of 76, 50%), and the majority did not have children (62 of 76, 82%; Supplemental Table S1).

The most important factor when selecting a residency program was program fit (54 of 74, 73%), and most residents were very satisfied with their program (45 of 74, 61%; Table 5). Domains plastic surgery residents were exposed to, and those they wished to have more exposure to, are summarized in Supplemental Table S2.

Table 5.

Survey Responses From Plastic Surgery Residents.a

| Mode | IQR | |

|---|---|---|

| I am satisfied with the operative experience in my program | Agree | 4-5 |

| I believe I have adequate aesthetic surgery training in residency | Neutral | 2-4 |

| I am confident with the job prospects in Canada for plastic surgeons | Neutral | 2-4 |

| I am concerned with the current job market for plastic surgeons | Agree | 3-4 |

| I have a good understanding of how best to determine the availability of jobs | Disagree | 2-3 |

| I believe there is a need for more plastic surgeons in Canada | Agree | 3-4 |

| I plan to practice in Canada | Strongly agree | 4-5 |

| I would consider relocating to another province if there were no jobs | Agree | 3-4 |

| I would consider relocating to another country if there were no jobs in Canada | Agree | 2-4 |

aRatings are on an Ordinal Likert-type Scale. 1 = strongly disagree, and 5 = strongly agree.

Almost half the residents indicated that their program did not have structured mentorship (34 of 74, 46%). The vast majority of residents were interested in pursuing additional training after their residency (66 of 74, 89%), with the most frequently cited reason being future employment and career goals (39 of 73, 53%). Over a third of respondents wished to practice in an academic setting (27 of 72, 38%; Supplemental Table S3).

Residents were subsequently asked a series of Likert-scale questions, from 1 to 5, where 1 indicated “strongly disagree” and 5 indicated “strongly agree.” When asked whether they were concerned about the current job market, most agreed (mode = 4; IQR= 3-5), with the most frequently reported concern that they would not be able to find a job in their desired geographic location (31 of 71, 44%). Few residents (mode = 2; IQR: 2-3) had a good understanding of how to determine the availability of jobs. When residents were asked whether they would consider relocating to another country, most agreed (mode = 4; IQR = 2-4; Table 5).

A number of themes were identified from free-text responses of residents asked whether there was anything additional their training program could do to help facilitate finding a permanent position. A total of 24 residents provided free-text responses, with the most common theme being “additional career planning assistance and mentorship.” Additional themes identified include “networking/connections,” “more elective time and longer electives,” and “increasing transparency of job prospects/openings.” (Supplemental Table S4).

Discussion

Although predictions from the plastic surgery workforce in 2007 warned of a shortage of surgeons,16 the results of this study suggest there will be adequate numbers in the coming years when comparing our future estimates to targets set by the CSPS (approximately 1 per 72 000). However, the average number of work hours reported by plastic surgeons has increased, likely representing a growing demand for plastic surgery services, a burden that is felt nationwide. This analysis has also identified a number of concerns among residents training in plastic surgery, which should be made initiatives for training programs.

“It is not a sustainable model to work over 90 hours a week and think that one can be balanced or have job satisfaction,” one surgeon wrote. “Burnout is occurring more rapidly…” wrote another. These quotes both highlight the burden felt by Canadian plastic surgeons who are faced with increasing wait times, work hour demands, and frequency of call schedules. Evidently, there has been little change in the last decade. A 2007 physician survey developed by the Royal College of Surgeons found that plastic surgeons worked a mean average 59 hours per week,23 and the same survey in 2014 was not significantly different.24 Figures generated from this survey show work week hour averages among Canadian Plastic Surgeons are likely on the rise. Although it remains unclear whether the number of surgeons in, or transitioning to, private aesthetic practice is increasing, the burden experienced by surgeons working in the public sector may be significantly impacted by these practice characteristics. Our study identified that nearly 10% self-identified as having an entirely aesthetic practice, with an additional 24% of surgeons indicating that their practice was composed of varying degrees of aesthetic surgery. We speculate that transition to aesthetic practice will increase as the frequency of call and number of work hours in community and academic centers continues to rise. It is imperative that administration and funding authorities account for these practice dynamics, as to best be able to support surgeons remaining in the public sector, providing necessary resources and hires. We encourage future studies to determine the number of surgeons transitioning to aesthetic practice, at what age, in addition to characteristics that may influence these choices. These findings will aid in more accurate workforce predictions.

These comparisons not only highlight that Canadian Plastic Surgeons are likely overworked but also the imperfect nature of physician to population ratios used as a surrogate measure of need. According to previous targets set by the CSPS, the ratio of surgeon per population estimated by this current survey is sufficient to meet demands. However, this model fails to take into account many important supply and demand characteristics.25,26 Alternative models, each with their own imperfections, have been explored and include demand-based approaches,27 needs-based approaches,28,29 and economic analyses.30,31 Specifically, in the plastic surgery literature, wait times have been used to estimate workforce demand.25 This study similarly highlighted the unmet need for plastic surgery services in Canada, concluding that wait times exceeded national benchmarks.32 The ideal surgeon to population ratio should therefore be adjusted to account for evolving practice models, disease burden, and physician demand.

Physician burnout has numerous serious sequelae, including poor patient care, increased medical errors, and decreased patient satisfaction.33-39 It has been associated with surgeon work hours, call burden, subspecialty choice, control over work schedule, reimbursement, work–family stressors, surgeon age, and surgeon gender.33,34,40-44 A recent study45 petitioned nearly 1700 practicing American Plastic Surgeons, identifying that a quarter had a quality of life lower than national norms. These rates were negatively correlated with work hours and night-call shifts, important factors identified in our own analysis. Burnout was also found to be associated with career satisfaction. However, despite long hours and frequent call, Canadian plastic surgeons self-reported excellent career satisfaction, expressing that they would recommend plastic surgery as a career to medical students. Nonetheless, as the demand for plastic surgeons increases further, institutional safeguards will play an essential role to protect the well-being of surgeons and residents.

The geographic distribution of plastic surgeons across Canada showed a far greater density in urban regions (Figure 2), consistent with previous assessments.16 Paradoxically, underserviced rural populations are generally more impoverished, sicker, and older.46 Workforce assessments concentrating only on national averages potentially conceal this disproportionate allocation of care, highlighted by studies in other disciplines47-51 as well as plastic surgery.52 Previous workforce assessments have recommended implementing retention incentives, rural elective training, and spousal support as ways to potentially improve the delivery of care to smaller communities.16 Relative to 2007, where the estimated rural cohort of plastic surgeons was approximately 12%, our study found that only 2% self-identified as practicing in a “rural” region, and a further 4% were working in regions where the population was 100 000 or less (small city/ town). This is in contrast to US estimates, which have highlighted that up to 15% of plastic surgeons are practicing in a small city or town,19 although the distribution is far from equal.52

Despite optimism expressed by surgeons, the majority (59%) of whom indicated that their group had plans to hire another plastic surgeon in the next 2 to 3 years, residents showed far less optimism concerning job prospects. Despite most residents planning to practice in Canada, the majority was concerned with the current job market, and few had a good understanding of how to determine the availability of jobs. As identified by our results, programs may be able to provide additional support to residents in the form of career planning assistance/mentorship, facilitated networking, more flexible elective time, and increasing transparency of job prospects/openings, among others. Mentorship, identified by residents as the most important resources programs can provide, has been described by Rohrich as the “least expensive and most powerful way to change the world.”53 If applied correctly, mentorship can be an immensely powerful tool and has been well studied in academic plastic surgery.54 Such programs can help guide trainees to domains and regions of active recruitment, or encourage further subspecialty training, ultimately facilitating the acquisition of a permanent position.

Consistent with previous reports,55 aesthetic training in plastic surgery residency remains an area of deficiency. In fact, surgeons were nearly 4 times more likely to identify aesthetic surgery/body contouring as a primary deficiency in their first 5 years of practice relative to other domains. Barriers to training56,57 and solutions for improving resident exposure to noninsured services have been previously explored.55 Resident aesthetic clinics, which provided residents with hands-on exposure to aesthetic surgery, have shown great promise58,59 but are not without limitations.60 As proposed elsewhere,55 programs should continue to foster aesthetic surgery training by providing residents with extrainstitutional elective experiences, particularly through outreach to nonacademic surgeons.

This study should be viewed in the context of several limitations. First, although our response rate was 49% for both surgeons and residents, respectively, our results are potentially impacted by response bias. Moreover, although the population of surgeons targeted were members of the CSPS (n = 438), the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada identified 569 licensed plastic surgeons in 2014 alone. The authors chose to only survey CSPS members, as the contact information for nonmembers was unavailable to us. Additionally, there were no systematic means of identifying and acquiring the e-mail addresses of the remaining 131 Canadian surgeons. This implies that licensed plastic surgeons not registered under the CSPS would be missed.22 Future studies should take into consideration the demographics of nonrespondents, which may ultimately influence workforce perceptions and skew the geographical distribution of surgeons described. Herein, the authors were unable to identify nonresponders, as all survey responses were anonymous. Nonetheless, response rates are consistent with previous studies of this nature.16,19 Second, there are inherent flaws in survey-based assessments of workforce, which have been discussed in this article. Thus, both averaged data (surgeon to population ratio) and geographical distribution of surgeons should be interpreted in the context of resource limitations, an important aspect of physician supply and demand that was not examined by this study. Future workforce analyses should aim to address these limitations.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that there are an adequate number of plastic surgeons practicing in Canada. Interpreted in the context of geographical distribution, there are evident deficiencies of care in rural regions, which are not accurately captured by national averages. The plastic surgery workforce may benefit from structured career mentorship in residency and improved transparency in hiring practices, particularly to attract young surgeons to smaller communities. There should also be strong consideration for a coordinated national approach to surgeon recruitment and succession planning.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, DS1-4_PSG_10.1177_2292550318800328 for The Canadian Plastic Surgery Workforce Analysis: Forecasting Future Need: L’analyse des effectifs canadiens en chirurgie plastique : l’anticipation des futurs besoins by Alexander Morzycki, Helene Retrouvey, Becher Alhalabi, Johnny Ionut Efanov, Sarah Al-Youha, Jamil Ahmad, and David T. Tang in Plastic Surgery

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: This paper was accepted for presentation at the 71st annual meeting of the Canadian Society of Plastic Surgeons in Winnipeg, MB, Canada. L’analyse des effectifs canadiens en chirurgie plastique: l’anticipation des futurs besoins. We would like to acknowledge the contribution of the members of the Canadian Plastic Surgery Research Collaborative.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Taylor DW. Finding Canada’s healthcare equilibrium. Healthc Manag Forum. 2012;25(2):48–54. doi:10.1016/j.hcmf.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tandon A, Murray CJ, Lauer JA, Evans DB. Measuring health system performance for 191 countries. Eur J Health Econ. 2002;3(3):145–148. doi:10.1007/s10198-002-0138-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sanmartin C, Shortt SED, Barer ML, Sheps S, Lewis S, McDonald PW. Waiting for medical services in Canada: Lots of heat, but little light. CMAJ. 2000;162(9):1305–1310. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario. Tackling the Doctor Shortage: A Discussion Paper.; 2004. http://www.cpso.on.ca/CPSO/media/uploadedfiles/policies/positions/resourceinitiative/Doctor-shortage.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2017.

- 5. Dauphinee WD, Buske L. Medical workforce policy-making in canada, 1993-2003: reconnecting the disconnected. Workforce. 2006;81(9):830–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sanmartin C, Ross N. Experiencing difficulties accessing first-contact health services in Canada difficultés d'accès aux soins de santé de première ligne au Canada. Healthc Policy. 2006;1(2):103–119. doi:10.12927/hcpol.2006.17882. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sullivan P. Concerns about size of MD workforce, medicine’s future dominate CMA annual meeting. CMAJ. 1999;161(8):946. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blendon RJ, Leitman R, Morrison I, Donelan K. Satisfaction with health systems in 10 nations. Health Aff. 1990;9(2):185–192. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.9.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lasser KE, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Access to care, health status, and health disparities in the United States and Canada: results of a cross-national population based survey. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(7):1300–1307. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.059402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Razik R, Cino M, Nguyen GC, et al. Employment prospects and trends for gastroenterology trainees in Canada: a nationwide survey. Can J Gastroenterol. 2013;27(11):647–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brandt MG, Scott GM, Doyle PC, Ballagh RH. Otolaryngology - Head and neck surgeon unemployment in Canada: a cross-sectional survey of graduating otolaryngology - Head and neck surgery residents. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;43:1–7. doi:10.1186/s40463-014-0037-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ouzounian M, Hassan A, Teng CJ, et al. The cardiac surgery workforce: a survey of recent graduates of Canadian training programs. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90(2):460–466. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Manusow JS, Buys YM, Bellan L. The underemployed ophthalmologist—results of a survey of recent ophthalmology graduates. Can J Ophthalmol / J Can d’Ophtalmologie. 2016;51(3):147–153. doi:10.1016/j.jcjo.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Khan S, Johnston L, Faimali M, Gikas P, Briggs TW. Matching residency numbers to the workforce needs. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2014;7(2):168–171. doi:10.1007/s12178-014-9208-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hawkins M. A Review of Physician to Population Ratios; 2003. https://www.merritthawkins.com/pdf/a-review-of-physician-to-population-ratios.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2017.

- 16. Macadam SA, Kennedy S, Lalonde D, Anzarut A, Clarke HM, Brown EE. The Canadian plastic surgery workforce survey: interpretation and implications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(7):2299–2306. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000261039.86003.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Williams TE, Ellison EC. Population analysis predicts a future critical shortage of general surgeons. Surgery. 2008;144(4):548–556. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pillsbury HC, Cannon CR, Sedory Holzer SE, et al. The workforce in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery: moving into the next millennium. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123(3):341–356. doi:10.1067/mhn.2000.109761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rohrich RJ, McGrath MH, Lawrence WT, Ahmad J. Assessing the plastic surgery workforce: a template for the future of plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(2):736–746. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181c830ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yang J, Jayanti MK, Taylor A, Williams TE, Tiwari P. The impending shortage and cost of training the future plastic surgical workforce. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;72(2):200–203. doi:10.1097/SAP.0b013e3182623941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Al-Taha MT, Al Youha SA, Samargandi O, Retrouvey H, Bezuhly M. Toward larger, more definitive trials. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139(2):580e doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000002964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. The Royal College of Physicans and Surgeons of Canada. Royal College Medical Workforce Knowledgebase: Licensed physician workforce. 2014. http://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/health-policy/medical-workforce-knowledgebase/mwk-licensed-physician-workforce-e.

- 23. Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. National Physician Survey. Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2007. Accessed December 15, 2017. Accessed December 15, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. National Physician Survey. Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cheung K, Sweetman A, Thoma A. Plastic surgery wait times in Ontario: a potential surrogate for workforce demand. Can J Plast Surg. 2012;20(4):229–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cheung K, Sweetman A, Thoma A. Challenges and strategies for determining workforce requirements in plastic surgery. Can J Plast Surg. 2012;20(4):245–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Denton FT, Gafni A, Spencer BG. Users and suppliers of physician services: a tale of two populations. Int J Heal Serv. 2009;39(1):189–218. doi:10.2190/HS.39.1.i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reinhardt UE. The GMENAC forecast: an alternative view. Am J Public Health. 1981;71(10):1149–1157. doi:Ar. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shipton D, Badley EM, Mahomed NN. Critical shortage of orthopaedic services in Ontario, Canada. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2003;85-A(0021-9355 (Print)):1710–1715. http://jbjs.org/content/85/9/1710.abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cooper RA. Weighing the evidence for expanding physician supply. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(9):705–714. doi:10.1177/153100350501700318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cooper RA, Getzen TE, McKee HJ, Laud P. Economic and demographic trends signal an impending physician shortage. Health Aff. 2002;21(1):140–154. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.21.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sigurdson L, Campbell E, Carr N. Canadian Society of Plastic Surgery Wait Times Benchmark Initiative; Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada: Canadian Society of Plastic Surgeons; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJ, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2009;250(3):463–471. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ac4dfd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(5):358–367. doi:200203050-00008 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. West CP, Huschka MM, Novotny PJ, et al. Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1071 doi:10.1001/jama.296.9.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Firth-Cozens J, Greenhalgh J. Doctors’ perceptions of the links between stress and lowered clinical care. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(7):1017–1022. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00227-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995–1000. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fahrenkopf AM, Sectish TC, Barger LK, et al. Rates of medication errors among depressed and burn out residents: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336(7642):488–491. doi:10.1136/bmj.39469.763218.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jones JW, Barge BN, Steffy BD, Fay LM, Kunz LK, Wuebker LJ. Stress and medical malpractice: organizational risk assessment and intervention. J Appl Psychol. 1988;73(4):727–735. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.73.4.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Balch CM, Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye L, et al. Surgeon distress as calibrated by hours worked and nights on call. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(5):609–619. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.06.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Martini S, Arfken CL, Churchill A, Balon R. Burnout comparison among residents in different medical specialties. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(3):240–242. doi:10.1176/appi.ap.28.3.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Becker JL, Milad MP, Klock SC. Burnout, depression, and career satisfaction: cross-sectional study of obstetrics and gynecology?? residents. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(5):1444–1449. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2006.06.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Golub JS, Johns MM, Weiss PS, Ramesh AK, Ossoff RH. Burnout in academic faculty of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery. Laryngoscope. 2008;118(11):1951–1956. doi:10.1097/MLG.0b013e31818226e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sargent MC, Sotile W, Sotile MO, Rubash H, Barrack RL. Stress and coping among orthopaedic surgery residents and faculty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(7):1579–1586. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15252111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Qureshi HA, Rawlani R, Mioton LM, Dumanian GA, Kim JYS, Rawlani V. Burnout Phenomenon in US Plastic Surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(2):619–626. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000000855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Curran V, Rourke J. The role of medical education in the recruitment and retention of rural physicians. Med Teach. 2004;26(3):265–272. doi:10.1080/0142159042000192055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Aneja S, Smith BD, Gross CP, et al. Geographic analysis of the radiation oncology workforce. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(5):1723–1729. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rosenthal MB, Zaslavsky A, Newhouse JP. The geographic distribution of physicians revisited. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6 I):1931–1952. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Thompson MJ, Lynge DC, Larson EH, Tachawachira P, Hart LG. Characterizing the general surgery workforce in rural America. Arch Surg. 2005;140:74–79. doi:10.1001/archsurg.140.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shipman Sa, Lan J, Chang CH, Goodman DC. Geographic maldistribution of primary care for children. Pediatrics. 2011;127(1):19–27. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-0150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ricketts TC. The migration of physicians and the local supply of practitioners: a five-year comparison. Acad Med. 2013;88(12):1913–1918. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bauder AR, Sarik JR, Butler PD, et al. Geographic variation in access to plastic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(Suppl 4):53 doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000472343.36900.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rohrich RJ. Mentors in medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(4):1087–1088. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000080319.87331.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Franzblau LE, Kotsis SV, Chung KC. Mentorship: concepts and application to plastic surgery training programs. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131(5):837e–843e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e318287a0c9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chivers QJ, Ahmad J, Lista F, et al. Cosmetic surgery training in canadian plastic surgery residencies: are we training competent surgeons? Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33(1):160–165. doi:10.1177/1090820X12467794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Freiberg A. Challenges in developing resident training in aesthetic surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 1989;22(3):184–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mahabir RC, Carr NJ, Thompson RP, Warren RJ. Aesthetic plastic surgery education: The Vancouver approach. Can J Plast Surg. 2002;10(1):19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Neaman KC, Hill BC, Ebner B, Ford RD. Plastic surgery chief resident clinics: the current state of affairs. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(2):626–633. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181df648c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pu LLQ, Thornton BP, Vasconez HC. The educational value of a resident aesthetic surgery clinic: A 10-year review. Aesthetic Surg J. 2006;26(1):41–44. doi:10.1016/j.asj.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Stadelmann WK, Rapaport D, Payne W, Shons AR, Krizek TJ. Residency training in aesthetic surgery: maximizing the residents’ experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101(7):1973–1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, DS1-4_PSG_10.1177_2292550318800328 for The Canadian Plastic Surgery Workforce Analysis: Forecasting Future Need: L’analyse des effectifs canadiens en chirurgie plastique : l’anticipation des futurs besoins by Alexander Morzycki, Helene Retrouvey, Becher Alhalabi, Johnny Ionut Efanov, Sarah Al-Youha, Jamil Ahmad, and David T. Tang in Plastic Surgery