Abstract

Purpose:

The aim of this study was to compare the complications of flap surgery in non-smokers and smokers and to determine how the incidence of complications was affected by the abstinence period from smoking before and after flap surgery.

Methods:

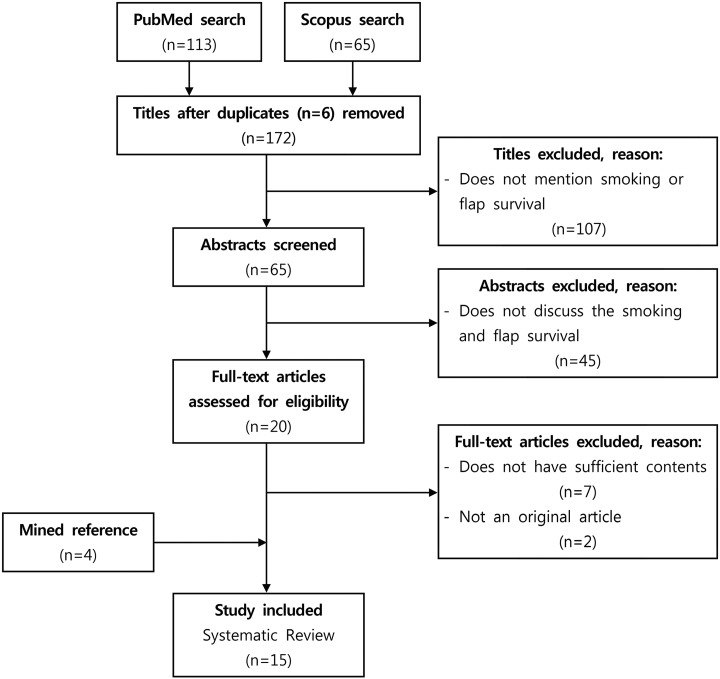

In PubMed and Scopus, terms “smoking” and “flap survival” were used, which resulted in 113 papers and 65 papers, respectively. After excluding 6 duplicate titles, 172 titles were reviewed. Among them, 45 abstracts were excluded, 20 full papers were reviewed, and finally 15 papers were analyzed.

Results:

Post-operative complications such as flap necrosis (P < .001), hematoma (P < .001), and fat necrosis (P = .003) occurred significantly more frequently in smokers than in non-smokers. The flap loss rate was significantly higher in smokers who were abstinent for 24 hours post-operatively than in non-smokers (n = 1464, odds ratio [OR] = 4.885, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.071-11.524, P < .001). The flap loss rate was significantly lower in smokers who were abstinent for 1 week post-operatively than in those who were abstinent for 24 hours post-operatively (n = 131, OR = 0.252, 95% CI = 0.074-0.851, P = .027). No significant difference in flap loss was found between non-smokers and smokers who were abstinent for 1 week preoperatively (n = 1519, OR = 1.229, 95% CI = 0.482-3.134, P = .666) or for 4 weeks preoperatively (n = 1576, OR = 1.902, 95% CI = 0.383-2.119, P = .812).

Conclusion:

Since smoking decreases the alveolar oxygen pressure and subcutaneous wound tissue oxygen, and nicotine causes vasoconstriction, smokers are more likely to experience flap loss, hematoma, or fat necrosis than non-smokers. Preoperative and post-operative abstinence period of at least 1 week is necessary for smokers who undergo flap operations.

Keywords: smoking, surgical flaps, post-operative complications, hematoma, fat necrosis, meta-analysis

Abstract

Objectif :

La présente étude visait à comparer les complications des opérations par lambeau chez les non-fumeurs et les fumeurs et à déterminer l’effet d’une période d’abstinence du tabagisme avant et après l’opération par lambeau sur l’incidence de complications.

Méthodologie :

Dans PubMed et Scopus, les chercheurs ont utilisé les termes smoking ET flap survival et extrait 113 articles et 65 articles, respectivement. Après avoir exclu six articles dédoublés, ils ont examiné 172 titres et ont exclu 45 résumés. Ils ont révisé 20 articles complets et analysé 15 articles.

Résultats :

Les complications postopératoires comme la nécrose du lambeau (P < 0,001), l’hématome (P < .001) et la nécrose graisseuse (P = 0,003) étaient considérablement plus fréquentes chez les fumeurs que chez les non-fumeurs. Le taux de perte du lambeau était significativement plus élevé chez les fumeurs qui s’étaient abstenus de fumer 24 heures après l’opération que chez les non-fumeurs (n = 1 464, rapport de cotes [RC] = 4,885, intervalle de confiance [IC] à 95 % = 2,071 à 11,524, P < 0,001). Le taux de perte du lambeau était considérablement plus faible chez les fumeurs abstinents pendant une semaine après l’opération que chez ceux qui l’avaient été seulement 24 heures (n = 131, RC = 0,252, IC à 95 % = 0,074 à 0,851, P = 0,027). Les chercheurs n’ont constaté aucune différence significative de perte du lambeau entre les non-fumeurs et les fumeurs qui étaient abstinents une semaine avant l’opération (n = 1 519, RC = 1,229, IC 95 % = 0,482 à 3,134, P = 0,666) ou quatre semaines avant l’opération (n = 1 576, RC = 1,902, IC 95 % = 0,383 à 2,119, P = 0,812).

Conclusion :

Puisque le tabagisme réduit la pression de l’oxygène dans les alvéoles et dans les tissus mous des lésions sous-cutanées et que la nicotine est responsable d’une vasoconstriction, les fumeurs sont plus susceptibles que les non-fumeurs de présenter une perte du lambeau, un hématome ou une nécrose graisseuse. Chez les fumeurs, une période d’abstinence d’au moins une semaine s’impose avant et après les opérations par lambeau.

Introduction

The deleterious effects of smoking on wound healing have been widely documented.1 Rohrich stated that plastic surgery patients should be advised to quit smoking 4 weeks prior to a surgical procedure, especially if the procedure requires the undermining of skin flaps.2

However, very few papers have assessed the non-smoking period before and after flap surgery. The aim of this study was to compare the complications of flap surgery in non-smokers and smokers and to systematically characterize the effect of the non-smoking period before and after flap surgery.

Methods

The search terms “smoking” and “flap survival” were used in a PubMed and Scopus search, which resulted in 113 papers and 65 papers, respectively. After excluding 6 duplicate titles, 172 titles were reviewed. Among the 172 titles, 107 titles were excluded, while 65 titles met our inclusion criteria (“smoking” and “flap survival” appeared in the title). Studies that did not discuss smoking and flap survival were excluded. Using these exclusion criteria, 45 abstracts were excluded and 20 full papers discussing smoking and flap survival were reviewed. Of these 20 full papers, 9 papers were excluded because they did not have sufficient content (2 studies) or had non-original content (7 studies), and 4 papers were added from the references of the articles identified in the searches. Ultimately, 15 studies were analyzed (Figure 1).3–17 We followed “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” guidelines in this study.18

Figure 1.

Selection process of the papers included in this study.

Studies that did not evaluate the effect of smoking on flap survival or microvascular anastomosis were excluded. No restrictions on language and publication forms were imposed. All the articles were read by 2 independent reviewers who extracted the data from the articles.

The data were summarized, and a statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS version 20 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York). The patients were classified as non-smokers (without a history of smoking) and smokers (with a history of smoking). Differences between the 2 groups were compared using the independent 2-sample t test.

In order to analyze the abstinence periods, non-smokers, 24-hour abstinent smokers, 1-week abstinent smokers, 4-week abstinent smokers, and 1-year abstinent smokers were grouped preoperatively and post-operatively. The odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval (CI), and P value were calculated.

Results

Among the 15 studies analyzed, 8 were level 2 studies and 7 were level 3 studies. No systematic review or meta-analysis was found (Supplement Data).

Flap Loss

Among 2246 patients from 13 studies, 138 (6.1%) cases of flap necrosis were reported.3–15 A total of 1426 patients from 12 studies3–7,9–15 were non-smokers and 820 patients from 13 papers3–15 were smokers. Flap necrosis occurred significantly more frequently in smokers (9.1%, 75/820 patients) than in non-smokers (4.4%, 63/1426 patients, P < .001 [independent 2-sample t test]; Table 1).

Table 1.

Rate of Flap Loss in Patients With or Without Smoking History.

| Author | Year | Area | Flap Name | With Smoking History | No Smoking History | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n | % | N | n | % | |||||

| Reus et al3 | 1990 | Cancer, trauma | Free flap | 93 | 5 | 5.4 | 51 | 3 | 5.9 | |

| Macnamara et al4 | 1994 | Head and neck | Radial fasciocutaneous, fibula | 20 | 2 | 10.0 | 40 | 4 | 10.0 | |

| Kinsella et al5 | 1995 | Facial skin | Transpositional, island flap | 38 | 8 | 21.0 | 478 | 7 | 1.5 | |

| Kroll et al6 | 1996 | Head and neck, breast | RAFF, jejunum, FTRAM | 309 | 26 | 8.4 | 342 | 20 | 5.8 | |

| Chang et al7 | 2000 | Breast | TRAM | 90 | 11 | 12.2 | 41 | 3 | 7.3 | |

| Maffi and Tran8 | 2001 | Traumatic wound | LD, gracilis, serratus | 28 | 4 | 14.3 | ||||

| Valentini et al9 | 2008 | Head and neck | Iliac crest, radial forearm | 77 | 2 | 2.6 | 41 | 4 | 9.8 | |

| Little et al10 | 2009 | Nose | Forehead flap | 48 | 6 | 12.5 | 157 | 5 | 3.2 | |

| Herold et al11 | 2011 | Upper/lower extremity, trunk | LD, ALT, DIEP | 17 | 1 | 5.9 | 132 | 9 | 6.8 | |

| Köse et al12 | 2011 | Lower extremity | Extended reverse sural A. flap | 2 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 12.5 | |

| Paddack et al13 | 2012 | Nose | NLF, PMFF | 56 | 5 | 8.9 | 51 | 1 | 2.0 | |

| Huang et al14 | 2012 | Forehead and temple | Extended DPCF | 4 | 1 | 25.0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | |

| Oh et al15 | 2012 | Diabetic foot | ALT, SCIP, AMT | 38 | 4 | 10.5 | 78 | 6 | 7.7 | |

| Total | 820 | 75 | 9.1 | 1426 | 63 | 4.4 | <.001 | |||

Abbreviations: A, artery; ALT, anterolateral thigh; AMT, anteromedial thigh; DIEP, deep inferior epigastric artery perforator; DPCF, deep-plane cervicofacial; FTRAM, free transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap; LD, latissimus dorsi; N, total patients; n, number of flap loss; NLF, nasolabial flap; PMFF, paramedian forehead interpolation flap; RAFF, rectus abdominis free flap; SCIP, superficial circumflex iliac artery; TRAM, transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous.

Flap loss according to the preoperative abstinence period

No significant differences were found between non-smokers and smokers who were abstinent for 1 week preoperatively (n = 1519, OR = 1.229, 95% CI = 0.482-3.134, P = .666), 4 weeks preoperatively (n = 1576, OR = 1.902, 95% CI = 0.383-2.119, P = .812), or 1 year preoperatively (n = 1438, OR = 1.967, 95% CI = 0.250-15.473, P = .520). No significant difference was found between smokers who were abstinent for 1 week preoperatively and those who were abstinent for 4 weeks preoperatively (n = 243, OR = 0.733, 95% CI = 0.217-2.474, P = .617). Likewise, no significant difference was found between smokers who were abstinent for 4 weeks preoperatively and those who were abstinent for 1 year preoperatively (n = 162, OR = 2.182, 95% CI = 0.241-19.771, P = .488; Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of Flap Loss According to Preoperative and Post-Operative Abstinence.

| Pre and Postoperative Abstinence Periods | Flap Loss | OR/(95% CI) | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | − | Total | ||||

| Preoperative | 1-week abstinence | 5 | 88 | 93 | 1.229 | .666 |

| Non-smoker | 63 | 1363 | 1426 | (0.482-3.134) | ||

| 4-week abstinence | 6 | 144 | 150 | 1.902 | .812 | |

| Non-smoker | 63 | 1363 | 1426 | (0.383-2.119) | ||

| 1-year abstinence | 1 | 11 | 12 | 1.967 | .520 | |

| Non-smoker | 63 | 1363 | 1426 | (0.250-15.473) | ||

| 4-week abstinence | 6 | 144 | 150 | 0.733 | .617 | |

| 1-week smoker | 5 | 88 | 93 | (0.217-2.474) | ||

| 1-year abstinence | 1 | 11 | 12 | 2.182 | .488 | |

| 4-week smoker | 6 | 144 | 150 | (0.241-19.771) | ||

| Post-operative | 24-hour abstinence | 7 | 31 | 38 | 4.885 | <.001 |

| Non-smoker | 63 | 1363 | 1426 | (2.071-11.524) | ||

| 1-week abstinence | 5 | 88 | 93 | 1.229 | .666 | |

| Non-smoker | 63 | 1363 | 1426 | (0.482-3.134) | ||

| 1-week abstinence | 5 | 88 | 93 | 0.252 | .027 | |

| 24-hour abstinence | 7 | 31 | 38 | (0.074-0.851) | ||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Flap loss according to the post-operative abstinence period

The flap loss rate was significantly higher in smokers who were abstinent for 24 hours post-operatively than in non-smokers (n = 1464, OR = 4.885, CI = 2.071-11.524, P < .001; Table 2). The flap loss rate was significantly lower in smokers who were abstinent for 1 week post-operatively than in those who were abstinent for 24 hours post-operatively (n = 131, OR = 0.252, 95% CI = 0.074-0.851, P = .027). However, no significant difference was found between non-smokers and smokers who were abstinent for 1 week post-operatively (n = 1519, OR = 1.229, 95% CI = 0.482-3.134, P = .666; Table 2).

Hematoma

Among 1049 patients from 4 papers, 56 (5.3%) cases of hematoma were reported.3,5,7,16 Of these patients, 570 (from 3 papers)3,5,7 were non-smokers and 479 (from 4 papers)3,5,7,16 were smokers. Hematoma formation occurred significantly more frequently in the smokers (9.2%, 44/479 patients) than in non-smokers (2.1%, 12/570 patients, P < .001 [independent 2-sample t test]; Table 3).

Table 3.

Hematoma Formation in Patients With or Without Smoking History.

| Author | Year | Area | Flap Name | With Smoking History | Without Smoking History | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt | H | % | Pt | H | % | |||||

| Reus et al3 | 1990 | Cancer, trauma | Free flap | 93 | 5 | 5.4 | 51 | 1 | 2.0 | |

| Kinsella et al5 | 1995 | Facial skin | Transpositional, island flap | 38 | 2 | 5.3 | 41 | 3 | 7.3 | |

| Chang et al7 | 2000 | Breast | TRAM | 90 | 6 | 6.7 | 478 | 8 | 1.7 | |

| Vandersteen et al16 | 2013 | Head and neck | Radial forearm, ALT, fibula | 258 | 31 | 12.0 | ||||

| Total | 479 | 44 | 9.2 | 570 | 12 | 2.1 | <.001 | |||

Abbreviations: ALT, anterolateral thigh; H, number of hematoma; Pt, total patients; TRAM, transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous.

Hematoma according to the preoperative abstinence period

No significant differences were found between non-smokers and smokers who were abstinent for 1 week preoperatively (n = 663, OR = 2.642, 95% CI = 0.909-7.681, P = .074), 4 weeks preoperatively (n = 720, OR = 1.938, 95% CI = 0.715-5.251, P = .194), or 1 year preoperatively (n = 582, OR = 4.227, 95% CI = 0.505-35.413, P = .184; Table 4). No significant difference was found between smokers who were abstinent for 1 week preoperatively and those who were abstinent for 4 weeks preoperatively (n = 243, OR = 0.733, 95% CI = 0.217-2.474, P = .617). Likewise, no significant difference was found between smokers who were abstinent for 4 weeks preoperatively and those who were abstinent for 1 year preoperatively (n = 162, OR = 2.182, 95% CI = 0.241-19.771, P = .488).

Table 4.

Comparison of Hematoma According to Preoperative and Post-Operative Abstinence.

| Pre and Postoperative Abstinence Periods | Hematoma | OR/(95% CI) | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | − | Total | ||||

| Preoperative | 1-week abstinence | 5 | 88 | 93 | 2.642 | .074 |

| Non-smoker | 12 | 558 | 570 | (0.909-7.681) | ||

| 4-week abstinence | 6 | 144 | 150 | 1.938 | .194 | |

| Non-smoker | 12 | 558 | 570 | (0.715-5.251) | ||

| 1-year abstinence | 1 | 11 | 12 | 4.227 | .184 | |

| Non-smoker | 12 | 588 | 570 | (0.505-35.413) | ||

| 4-week abstinence | 6 | 144 | 150 | 0.733 | .617 | |

| 1-week smoker | 5 | 88 | 93 | (0.217-2.474) | ||

| 1-year abstinence | 1 | 11 | 12 | 2.182 | .488 | |

| 4-week smoker | 6 | 144 | 150 | (0.241-19.771) | ||

| Post-operative | 24-hour abstinence | 1 | 37 | 38 | 1.257 | .828 |

| Non-smoker | 12 | 558 | 570 | (0.159-9.930) | ||

| 1-week abstinence | 5 | 88 | 93 | 2.642 | .074 | |

| Non-smoker | 12 | 558 | 570 | (0.909-7.681) | ||

| 1-week abstinence | 5 | 88 | 93 | 2.102 | .504 | |

| 24-hour abstinence | 1 | 37 | 38 | (0.237-18.619) | ||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Hematoma according to the post-operative abstinence period

The hematoma rate did not differ significantly in non-smokers and smokers who were abstinent for 24 hours post-operatively (n = 608, OR = 1.257, 95% CI = 0.159-9.930, P = .828; Table 4). No significant difference was found between non-smokers and smokers who were abstinent for 1 week post-operatively (n = 663, OR = 2.642, 95% CI = 0.909-7.681, P = .074). Likewise, no significant difference was found between smokers who were abstinent for 24 hours or 1 week post-operatively (n = 131, OR = 2.102, 95% CI = 0.237-18.619, P = .504).

Fat Necrosis

Among 750 patients from 2 papers, 150 (20%) cases of fat necrosis were reported.7,17 Of these patients, 638 (from 2 papers)7,17 were non-smokers and 112 (from 2 papers)7,17 were smokers. Fat necrosis occurred significantly more frequently in smokers (30.4%, 34/112 patients) than in non-smokers (18.2%, 116/638 patients, P = .003 [independent 2-sample t test]; Table 5).

Table 5.

Fat Necrosis in Patients With or Without Smoking History.

| Author | Year | Area | Flap Name | With Smoking History | Without Smoking History | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt | Fn | % | Pt | Fn | % | |||||

| Chang et al7 | 2000 | Breast | TRAM | 90 | 20 | 22.2 | 478 | 31 | 6.5 | |

| Peeters et al17 | 2009 | Breast | DIEP | 22 | 14 | 63.6 | 160 | 85 | 53.1 | |

| Total | 112 | 34 | 9.2 | 638 | 116 | 18.2 | .003 | |||

Abbreviations: DIEP, deep inferior epigastric artery perforator; Fn, number of fat necrosis; Pt, total patients; TRAM, transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous.

Discussion

All the studies analyzed were retrospective database studies because no randomized controlled studies were available on the topic of smoking and flap survival. The limitations of this study are the limited number of studies, since most of the papers we initially identified did not present details regarding the smoking amount (pack-years), smoking periods, or preoperative and post-operative abstinence periods. In this article, we were not able to consider other risk factors (eg, diabetes and hypertension) that may have influenced the occurrence of complications.

In our review, we found that post-operative complications such as flap necrosis (P < .001), hematoma (P < .001), and fat necrosis (P = .003) occurred significantly more frequently in smokers than in non-smokers.

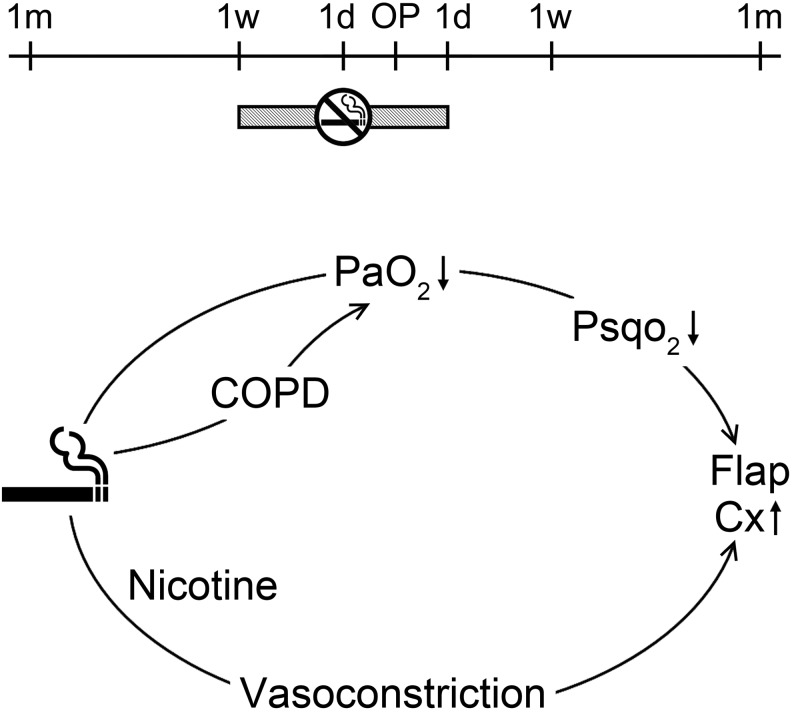

The flap loss rate was significantly higher in smokers who were abstinent for 24 hours post-operatively than in non-smokers (n = 1464, OR = 4.885, CI = 2.071-11.524, P < .001). The flap loss rate was significantly lower in smokers who were abstinent for 1 week post-operatively than in those who were abstinent for 24 hours post-operatively (n = 131, OR = 0.252, CI = 0.074-0.851, P = .027). Thus, it is suggested that a post-operative abstinence period of at least 1 week is necessary for smokers who undergo a flap operation (Figure 2, upper).

Figure 2.

Mechanism of smoking and abstinence periods. Upper: Preoperative and post-operative abstinence periods for smokers who undergo a flap operation. Lower: Mechanism of effect of smoking on flap loss. COPD indicates chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Cx, complication; d, day; m, month; Pao 2, alveolar oxygen pressure; Psqo 2, subcutaneous wound tissue oxygen; w, week.

No significant differences were found in flap loss between non-smokers and smokers who were abstinent for 1 week preoperatively (n = 1519, OR = 1.229, 95% CI = 0.482-3.134, P = .666) or 4 weeks preoperatively (n = 1576, OR = 1.902, 95% CI = 0.383-2.119, P = .812). Although a preoperative abstinence period of 4 weeks is recommended, we suggest that a preoperative abstinence period of at least 1 week is necessary for smokers who plan to undergo a flap operation.

The cardiovascular responses to nicotine are due to stimulation of the sympathetic ganglia and the adrenal medulla, together with the discharge of catecholamines from sympathetic nerve endings and chromaffin tissues of various organs.19 Nicotine also activates the sympathomimetic response in chemoreceptors of the aortic and carotid bodies, which results in vasoconstriction, tachycardia, and elevated blood pressure.20 Any decrease in the alveolar oxygen pressure (Pao 2) due to smoking would lead to a decrease in subcutaneous wound tissue oxygen (Psqo 2) as well, but the effects of smoking on Pao 2 tend to be more chronic than acute. Smoking is a risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). In COPD, decreased Pao 2 can lead to decreased baseline subcutaneous wound tissue oxygen (Psqo 2) in smokers. Vasoconstriction due to nicotine intake in patients with an already decreased Psqo 2 due to COPD can lead to flap loss (Figure 2, lower).21 Since smoking reduces Pao 2 and Psqo 2, and nicotine causes vasoconstriction, smokers are more likely to experience flap loss, hematoma, or fat necrosis than non-smokers. Preoperative and post-operative abstinence periods of at least 1 week are necessary for smokers who undergo flap operations.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, DS1_PSG_10.1177_2292550317749509 for Smoking and Flap Survival Le tabagisme et la survie des lambeaux by Kun Hwang, Ji Soo Son, and Woo Kyung Ryu in Plastic Surgery

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Hun Kim, BHS, Department of Plastic Surgery, Inha University School of Medicine, for his effort in making figures and statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Level of Evidence: Level 2, Risk

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by a grant from National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2017R1A2B4005787).

ORCID iD: Kun Hwang  http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1994-2538

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1994-2538

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Fan KL, Patel KM, Mardini S, Attinger C, Levin LS, Evans KK. Evidence to support controversy in microsurgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(3):595e–608e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rohrich RJ. Cosmetic surgery and patients who smoke: should we operate? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106(1):137–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reus WF, III, Colen LB, Straker DJ. Tobacco smoking and complications in elective microsurgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89(3):490–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Macnamara M, Pope S, Sadler A, Grant H, Brough M. Microvascular free flaps in head and neck surgery. J Laryngol Otol. 1994;108(11):962–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kinsella JB, Rassekh CH, Hokanson JA, Wassmuth ZD, Calhoun KH. Smoking increases facial skin flap complications. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999;108(2):139–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kroll SS, Schusterman MA, Reece GP, et al. Choice of flap and incidence of free flap success. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98(3):459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chang DW, Reece GP, Wang B, et al. Effect of smoking on complications in patients undergoing free TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(7):2374–2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maffi TR, Tran NV. Free-tissue transfer experience at a county hospital. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2001;17(6):431–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Valentini V, Cassoni A, Marianetti TM, et al. Diabetes as main risk factor in head and neck reconstructive surgery with free flaps. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19(4):1080–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Little SC, Hughley BB, Park SS. Complications with forehead flaps in nasal reconstruction. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(6):1093–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Herold C, Gohritz A, Meyer-Marcotty M, et al. Is there an association between comorbidities and the outcome of microvascular free tissue transfer? J Reconstr Microsurg. 2011;27(2):127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Köse R, Mordeniz C, Şanli Ç. Use of expanded reverse sural artery flap in lower extremity reconstruction. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50(6):695–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paddack AC, Frank RW, Spencer HJ, Key JM, Vural E. Outcomes of paramedian forehead and nasolabial interpolation flaps in nasal reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;138(4):367–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang AT, Tarasidis G, Yelverton JC, Burke A. A novel advancement flap for reconstruction of massive forehead and temple soft-tissue defects. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(8):1679–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oh TS, Lee HS, Hong JP. Diabetic foot reconstruction using free flaps increases 5 year-survival rate. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013;66(2):243–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vandersteen C, Dassonville O, Chamorey C, et al. Impact of patient comorbidities on head and neck microvascular reconstruction. A report on 423 cases. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270(5):1741–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peeters WJ, Nanhekhan L, Van Ongeval C, Favré G, Vandevoort M. Fat necrosis in deep inferior epigastric perforator flaps: an ultrasound-based review of 202 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(6):1754–1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gebber GL. Neurogenic basis for the rise in blood pressure evoked by nicotine in the cat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1969;166(2):255–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goodman LS, Gillman A. Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 6th ed New York, NY: Macmillan; 1980:213. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jensen JA, Goodson WH, Hopf HW, Hunt TK. Cigarette smoking decreases tissue oxygen. Arch Surg. 1991;126(9):1131–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, DS1_PSG_10.1177_2292550317749509 for Smoking and Flap Survival Le tabagisme et la survie des lambeaux by Kun Hwang, Ji Soo Son, and Woo Kyung Ryu in Plastic Surgery