Short abstract

Background

Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI) is a promising perfusion method and may be useful in evaluating radiation-induced changes in normal-appearing brain tissue.

Purpose

To assess whether radiotherapy induces changes in vascular permeability (Ktrans) and the fractional volume of the extravascular extracellular space (Ve) derived from DCE-MRI in normal-appearing brain tissue and possible relationships to radiation dose given.

Material and Methods

Seventeen patients with glioblastoma treated with radiotherapy and chemotherapy were included; five were excluded because of inconsistencies in the radiotherapy protocol or early drop-out. DCE-MRI, contrast-enhanced three-dimensional (3D) T1-weighted (T1W) images and T2-weighted fluid attenuated inversion recovery (T2-FLAIR) images were acquired before and on average 3.3, 30.6, 101.6, and 185.7 days after radiotherapy. Pre-radiotherapy CE T1W and T2-FLAIR images were segmented into white and gray matter, excluding all non-healthy tissue. Ktrans and Ve were calculated using the extended Kety model with the Parker population-based arterial input function. Six radiation dose regions were created for each tissue type, based on each patient’s computed tomography-based dose plan. Mean Ktrans and Ve were calculated over each dose region and tissue type.

Results

Global Ktrans and Ve demonstrated mostly non-significant changes with mean values higher for post-radiotherapy examinations in both gray and white matter compared to pre-radiotherapy. No relationship to radiation dose was found.

Conclusion

Additional studies are needed to validate if Ktrans and Ve derived from DCE-MRI may act as potential biomarkers for acute and early-delayed radiation-induced vascular damages. No dose-response relationship was found.

Keywords: Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, DCE-MRI, radiation therapy/oncology, radiation effects, normal-appearing brain tissue, glioblastoma

Introduction

The vascular hypothesis of late delayed radiation-induced brain injury argues that white matter necrosis is secondary to vascular damage and ischaemia (1). Vascular damage, such as vessel wall thickening, vessel dilation, and especially reduction of vascular endothelial cell density and blood–brain barrier (BBB) damage after radiation exposure, has been described previously (1–5), and it was recently suggested that vascular smooth cell and pericyte degeneration might be the cause (6). While BBB damage is well recognized after radiotherapy, several publications suggest that vascular endothelial cell death and density reductions can play the primary role in the development of radiation-induced brain injury (2–4). Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI) is a promising perfusion method, which can play a role in treatment response evaluation, prognosis, and therapy individualization in patients with high-grade gliomas and is considered the standard MRI approach for assessing vascular permeability (7, 8). Pharmacokinetic modeling using the extended Kety model of DCE-MRI data allows estimation the volume of extravascular extracellular space (EES) per unit volume of tissue (Ve, dimensionless), volume transfer constant from blood plasma to the EES (Ktrans, mm−1), and volume of blood plasma per unit volume of tissue (Vp, dimensionless) (9). While not universally established, Ktrans can be used as a quantitative measure of BBB permeability and Ve can be considered to have an inverse relationship with cell density (10,11). However, most DCE-MRI studies in gliomas have disregarded Ve (11). Radiation-induced injury in normal brain tissue has been studied using DCE-MRI, for example by Cao et al., who found significantly increasing Ktrans and Vp values during and after fractionated radiotherapy (FRT). Furthermore, increases in Ktrans and Vp were found to be dependent on radiation dose given up to one month after FRT. They found significant correlations between changes in Ktrans and Vp and neuropsychological tests at six months after FRT concluding that early radiation-induced vascular changes may predict neurocognitive impairment and addressing the need for additional studies (12). However, Ve was not included in their analysis and to our knowledge, no additional studies has been published analyzing DCE-MRI-derived parameters in normal-appearing brain tissue after radiotherapy in patients with glioma. Given the reduction of vascular endothelial cell density after radiation exposure and considering the suggested inverse relationship to cell density in tumors (10,11), Ve should increase after radiotherapy and thus may be a potential biomarker for radiation-induced vascular changes. The Stupp treatment regimen for glioblastoma increases the two-year survival from 10% to 26% (13). However, diffuse invasion of tumor cells into the surrounding brain and failure to deliver sufficient dosage of chemotherapeutic agents across the BBB still makes current treatment inadequate (14,15). Treatment sequelae, i.e. radiation-induced neurocognitive impairment, may have considerable negative effects on the patients’ quality of life, why the balance between benefits and harms of radiotherapy is important in clinical treatment decision-making (1,5,16–19). Given the late occurrence of neurocognitive impairment, it is important to find imaging biomarkers for assessment and prediction. Early detection of radiation-induced vascular damages is therefore important to aid the clinicians in their decision-making (1,5,18). The aim was to investigate whether radiotherapy induces changes in Ktrans and Ve in normal-appearing brain tissue in patients with glioblastoma as well as whether a possible dose-response relationship exists.

Material and Methods

Patients

Seventeen patients were included in this study. Inclusion criteria were patients aged ≥ 18 years with newly detected glioma World Health Organization (WHO) grade III–IV proven by histopathology and scheduled for FRT and chemotherapy. This study was done in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee (Regionala etikprövningsnämnden i Uppsala, approval no. 2011/248). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. All patients underwent surgical resection or biopsy. Baseline MRI was performed before FRT (pre-FRT); post-FRT examinations were scheduled consecutively after the completion of FRT (FRTPost-1, FRTPost-2, FRTPost-3, and FRTPost-4). The FRT was delivered using 6-MV photons with intensity modulated radiation therapy or volumetric arc therapy. Concomitant chemotherapy was administrated daily during FRT with temozolomide followed by adjuvant chemotherapy starting four weeks after completed FRT according to Stupp et al. (13). In cases of tumor progression or recurrence, a combination of temozolomide, bevacizumab and/or procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine (in combination, also known as PCV) was administrated.

Exclusion criteria

Patients deviating from a prescribed total radiation dose of 60 Gy or with less than two performed examinations (early drop-outs) were excluded from analysis in this study.

Image acquisition

All examinations were performed using a consistent imaging protocol on a 1.5-T Siemens Avanto Fit (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) and included DCE-MRI, variable flip angle (VFA) images for T1-map estimation, T2-weighted fluid attenuated inversion recovery (T2-FLAIR) images, and contrast-enhanced (CE) three-dimensional (3D) T1-weighted (T1W) images.

Imaging parameters were as follows:

DCE-MRI (2D-EPI [gradient echo]; TR/TE/flip angle [FA] = 3/0.98/90; matrix = 192 × 118; 1.25 × 1.25 × 5 mm; time resolution = 3.56 s; dynamic volumes = 80; acquisition time = 4.44 min; 16 slices). A standard dose bolus of 5 mL gadolinium-based contrast agent (Gadovist, Bayer AG, Berlin, Germany) was administered to all patients during the DCE-MRI using a power-injector at a rate of 2 mL/s. A second standard dose bolus was administrated during a subsequent dynamic susceptibility contrast (DSC)-MRI (not evaluated in this study);

VFA (TR/TE/FA 5 and 10 = 3/0.98/5 and 10; matrix = 192 × 118; 1.25 × 1.25 × 5 mm; 16 slices). Two VFA acquisitions were performed, one with a FA of 5° and one with a FA of 10°. Each acquisition was performed three times;

CE-T1W imaging (3D-Gradient Echo; TR/TE/inversion time/FA = 1170/4.17/600/15; matrix = 256 × 256; 1 × 1 × 1 mm; 208 slices);

T2-FLAIR (axial-2D T2-weighted; TR/TE/inversion time/FA = 6000/120/2000/90; matrix = 288 × 203; 0.53 × 0.53 × 5 mm; 26 slices.

Computed tomography (CT) for radiotherapy planning was acquired with a Philips, Brilliance Big Bore (Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands) with a voxel size of 0.525 × 0.525 × 2 mm.

Pharmacokinetic analysis

Before pharmacokinetic analysis, the elastix software package (elastix.isi.uu.nl) was used to perform rigid image registration for each time frame in the dynamic series, as well as for each VFA acquisition with a varied FA utilizing the first time point as reference (20,21). For each FA, the images were averaged to reduce noise, excluding the first VFA acquisition due to saturation effects. A T1-map was obtained through the VFA method (22,23). Bolus arrival time was found by searching the best fit for the extended Kety model (24) using the Parker population-based arterial input function (AIF) (25). Time frames before bolus arrival were averaged to create the baseline signal. A contrast agent concentration time curve was obtained from the baseline signal and the dynamic series, excluding T2* effects, and using a relaxivity of 5.2 mmol−1s−1. The extended Kety model was applied to the contrast agent concentration time curve along with the T1-map, thus obtaining parameter maps of Ktrans, Ve, and Vp. In this study, Vp was excluded from the analysis because it was highly influenced by noise. All processing steps, as described above, included in the pharmacokinetic analysis were performed using the MICE toolkit (26) if not stated otherwise.

Data post-processing

Ktrans and Ve parameter maps, T2-FLAIR images and dose-plan CT images were co-registered to the pre-FRT CE-T1W images for each patient and examination using the SPM12 toolbox (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London, UK). GM and WM probability maps were segmented from CE-T1W images and registered T2-FLAIR images (27) using the segmentation tool in the SPM12 toolbox, also, co-registered to pre-FRT CE-T1W images. WM and GM maps were defined as a partial volume fraction > 70%. Normal-appearing brain tissue was defined as brain tissue appearing normal on CE-T1W and T2-FLAIR images, thus excluding contrast-enhancing tissue, white matter signal changes (e.g. edema or radiation-induced hyperintensity), resection cavity, tumor progression and recurrence, if present on CE-T1W and/or T2-FLAIR images (checked by an experienced neuroradiologist). Registered radiation dose plans were divided as follows: 0–10, 10–20, 20–30, 30–40, 40–50, and 50–60 Gy, creating six dose regions for each tissue type.

Statistical analysis

Mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for patient demographics analysis. For descriptive analysis, mean, standard error of mean (SEM) together with mean and SEM of difference between post-FRT and pre-FRT were calculated globally, incorporating all values irrespective of received radiation dose (global Ktrans and Ve). A Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed ranks test was used to compare post-FRT data with pre-FRT data. This was performed for absolute global values in both GM and WM. Derived P values are two-sided and presented as exact values; P values < 0.05 were considered significant. A linear regression model was applied to assess a possible dose-response relationship concerning relative change (post-FRT/pre-FRT) between post-FRT and pre-FRT and received radiation dose. Graphpad Prism 7 for Mac (Graphpad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis and graph design.

Results

Patients

Five patients were excluded due to early drop-out, i.e. only baseline MRI was performed (n = 2) or deviation from the prescribed total dose of 60 Gy (n = 3). Data from 12 patients were analyzed (mean age = 55.9 years; SD = 10.8 years). All had a histopathological diagnosis of glioblastoma (WHO grade IV). Eleven patients received a dose of 2.0 Gy/fraction and one patient 2.2 Gy/fraction, total radiation dose for all were 60 Gy. Nine DCE-MRI acquisitions were missing or inconsistent and thus excluded, yielding a total of 51 MRI examinations. Pre-FRT examination was performed on average (SD, number of patients) 6.2 (4.1, 11 patients) days before start of FRT, and four post-FRT examinations were performed 3.3 (4.7, 11 patients), 30.6 (11.0, eight patients), 101.6 (16.5, nine patients), and 185.7 (18.4, 10 patients) days after end of FRT. Six patients were given temozolomide during FRTPost-2, three patients during FRTPost-3, and one patient during FRTPost-4. PCV was given during FRTPost-2 in one patient, and bevacizumab was given during FRTPost-2 in one patient and during FRTPost-4 in four patients.

Changes in Ktrans and Ve after radiotherapy

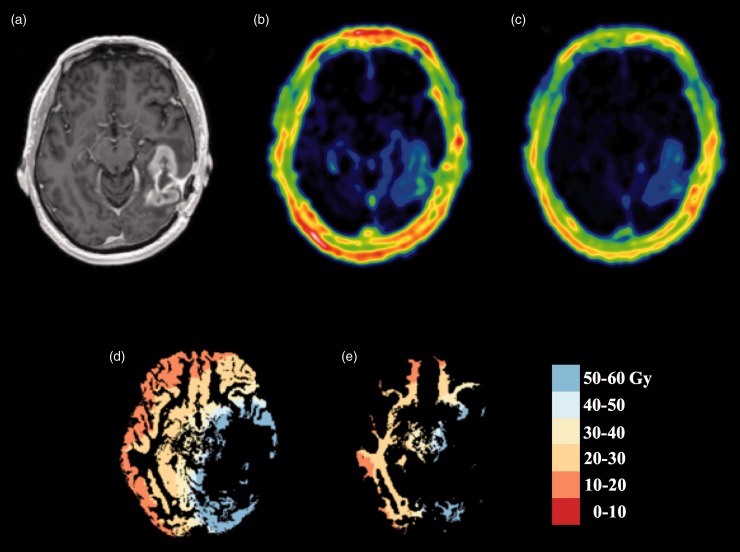

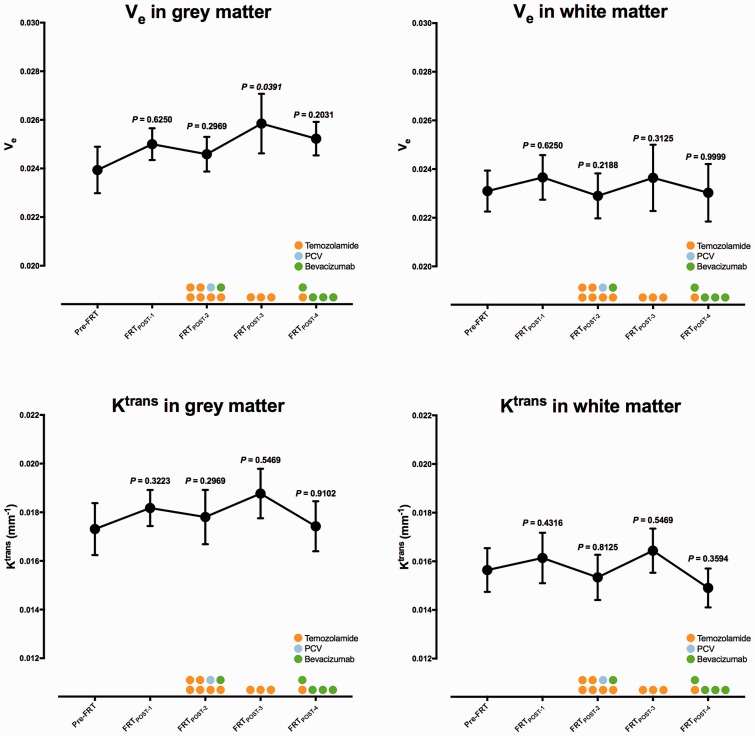

Representative pre-FRT CE-T1W images of Ktrans- and Ve-maps and segmented GM- and WM-maps with derived dose regions and excluded abnormal tissue are shown in Fig 1. Global mean Ktrans and Ve with SEM are graphically described in Fig. 2 and presented as values in Table 1. The global mean difference between post-FRT and pre-FRT for Ktrans and Ve are graphically presented in Fig. 3. In GM, Ktrans demonstrated non-significant changes (P > 0.05). Mean Ktrans increased at FRTPost-1 (0.00082 ± 0.00113 min−1, ΔKtrans ± SEM). At FRTPost-2, mean Ktrans decreased from the mean value observed at FRTPost-1, though it was still higher than baseline (0.00069 ± 0.00053 min−1). The largest difference in mean Ktrans was found at FRTPost-3 (0.00118 ± 0.00088 min−1), subsequently at FRTPost-4, mean Ktrans decreased below baseline (–0.00021 ± 0.00065 min−1). Mean Ktrans in WM demonstrated a similar pattern (0.00092 ± 0.00123 min−1 at FRTPost-1, 0.00069 ± 0.00081 min−1 at FRTPost-2, 0.00107 ± 0.00115 min−1 at FRTPost-3, and −0.00087 ± 0.00081 min−1 at FRTPost-4). Overall, mean Ve demonstrated a similar pattern as Ktrans with mostly non-significant changes (P > 0.05). In GM, mean Ve increased at FRTPost-1 (0.00064 ± 0.00101, ΔVe ± SEM). Mean Ve further increased at FRTPost-2 (0.00056 ± 0.00069) and significantly at FRTPost-3 (0.00208 ± 0.00123, P=0.0391). At FRTPost-4, mean Ve decreased from the mean value at FRTPost-3, though it was higher than FRTPost-2 (0.00145 ± 0.00118). A similar pattern of mean Ve was demonstrated in WM (0.00061 ± 0.00100 at FRTPost-1, 0.00069 ± 0.00086 at FRTPost-2, and 0.00144 ± 0.00095 at FRTPost-3); however, at FRTPost-4, mean Ve decreased below FRTPost-2, but was still higher than baseline. No significant dose-response relationship was found for Ktrans or Ve (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Pre-FRT CE-T1W image (a, top left) axial slice showing contrast-enhancement and resection cavity. Increased vascular permeability and increased EES volume are shown in the contrast-enhancing tumor in Ktrans (b, top middle) and Ve (c, top right) images. Segmented gray (d, bottom left) and white matter (e, bottom right) maps with color-coded derived dose regions are shown in the bottom row.

Fig. 2.

Global mean and SEM for both Ktrans (mm−1) and Ve (dimensionless) graphically presented for each examination in consecutive order with derived P values from a Wilcoxon matched-pair signed ranks test comparing post-FRT data with pre-FRT data. Color circles describes the number of patients given chemotherapy (including drug) and during which examinations.

Table 1.

Global mean and SEM and mean difference relative to pre-FRT with SEM for Ktrans and Ve in GM and WM for all consecutive examinations.

| Pre-FRT | FRTPost-1 | FRTPost-2 | FRTPost-3 | FRTPost-4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ktrans in GM | |||||

| Mean Ktrans ± SEM | 0.0173 ± 0.0011 | 0.0182 ± 0.0007 | 0.0178 ± 0.0011 | 0.0188 ± 0.0010 | 0.0174 ± 0.0010 |

| Mean ΔKtrans ± SEMP value | N/A | 0.00082 ± 0.001130.3223 | 0.00069 ± 0.000530.2969 | 0.00118 ± 0.000880.5469 | –0.00021 ± 0.000650.9102 |

| Ve in GM | |||||

| Mean Ve ± SEM | 0.0239 ± 0.0010 | 0.0250 ± 0.0007 | 0.0246 ± 0.0007 | 0.0259 ± 0.0012 | 0.0252 ± 0.0007 |

| Mean ΔVe ± SEMP value | N/A | 0.00064 ± 0.001010.4922 | 0.00056 ± 0.000690.2969 | 0.00208 ± 0.001230.0391 | 0.00145 ± 0.001180.2031 |

| Ktrans in WM | |||||

| Mean Ktrans ± SEM | 0.0156 ± 0.0009 | 0.0161 ± 0.0010 | 0.0153 ± 0.0009 | 0.0164 ± 0.0009 | 0.0149 ± 0.0008 |

| Mean ΔKtrans ± SEMP value | N/A | 0.00092 ± 0.001230.4316 | 0.00069 ± 0.000810.8125 | 0.00107 ± 0.001150.5469 | –0.00087 ± 0.000810.3594 |

| Ve in WM | |||||

| Mean Ve ± SEM | 0.0231 ± 0.0008 | 0.0238 ± 0.0009 | 0.0229 ± 0.0009 | 0.0236 ± 0.0014 | 0.0230 ± 0.0012 |

| Mean ΔVe ± SEMP value | N/A | 0.00061 ± 0.001000.6250 | 0.00069 ± 0.000860.2188 | 0.00144 ± 0.000950.3125 | 0.00019 ± 0.001540.9999 |

P values are two-sided and derived from a Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed ranks test comparing absolute post-FRT data with pre-FRT data. A significant difference was found for Ve in GM at FRTPost-3 (P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Global absolute mean difference relative to pre-FRT with SEM for both Ktrans (mm−1) and Ve (dimensionless) graphically presented for each examination in consecutive order with derived P values from a Wilcoxon matched-pair signed ranks test comparing post-FRT data with pre-FRT data.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study assessing radiation-induced vascular damages using Ktrans and Ve derived from DCE-MRI in patients after FRT. Ve in GM increased significantly (P = 0.0391) at FRTPost-3; otherwise, we found non-significant changes, although higher mean Ktrans and Ve after FRT. This may suggest increased BBB permeability (increasing Ktrans values) and decreased cell density (increasing Ve indicating larger EES) in normal-appearing brain tissue after FRT. Neither Ktrans nor Ve demonstrated any relationship with radiation dose.

The vascular hypothesis for acute and early delayed radiation-induced changes in normal-appearing brain tissue has been described in several publications (1,3,12,28). However, reports of radiation-induced necrosis in the absence of vascular changes exist (1,29). There is an increasing body of data suggesting that the vascular hypothesis alone cannot explain radiation-induced changes in normal-appearing brain tissue (1,5,30,31). While the underlying mechanism remains unclear, it is now recognized that the process is dynamic and interacting, involving glial cells as well as vascular endothelial cells (1,30,31).

Ktrans and Ve are not entirely established as biomarkers of vascular damage. Ve is a direct estimate of the EES volume (9) and the EES is presumed to have an inverse relationship with cell density in tumors (10,11). Moreover, the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) is also presumed to reflect the size of the EES (11). ADC and mean diffusivity, which is similar to ADC (32,33), have been found to increase in normal-appearing white matter after radiotherapy (34,35). Based on this, we would expect to find increased Ve after radiotherapy. However, in a correlation study, Mills et al. did not find any correlation between Ve and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) concluding that the information provided by Ve and ADC is not fully understood and that lack of correlation may be due to methodological variation (11). Moreover, Ktrans as a biomarker for BBB permeability has been studied extensively; however, current data mostly apply to tumors (8). We did not find any significant increase of Ve or Ktrans; still, derived mean Ve and Ktrans increased post-FRT, thus in agreement with the described theory of the decrease in vascular cell density and increasing BBB permeability in normal-appearing brain tissue exposed to radiation (1–4).

Only a few studies have assessed radiation-induced changes in normal-appearing brain tissue after FRT in patients with glioblastomas using different imaging methods. Most common is brain perfusion assessment with DSC-MRI (36). However, only one publication has used DCE-MRI to study radiation-induced changes in normal-appearing brain tissue after FRT in patients, even if this is a promising technique for clinical brain tumor imaging. Cao et al. evaluated BBB permeability with Ktrans as a biomarker derived from DCE-MRI data. They found significantly increasing Ktrans during RFT (at week 6) and non-significant increases one and six months after FRT (12). At one and six months, Ktrans was lower than compared to week 6 during FRT (12). Using DSC-MRI, Lee et al. observed a dose-dependent significant decline in vessel density and an increase in vascular permeability two months after FRT (37). Both results are similar to ours; however, some differences need to be addressed. In the paper by Cao et al., significant increases were only found during FRT, a time point not included in our study. Furthermore, differences between GM and WM were not considered, higher contrast agent dose were administrated (0.1 mL/kg compared to 5 mL in our study) and Cao et al. used larger dose intervals. Moreover, comparing results derived from DSC-MRI, as used in Lee et al., and DCE-MRI is difficult and should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, at FRTPost-3 (101.6 days after FRT), both Ktrans and Ve increased from previous examination (FRTPost-2, which was generally preceded by a recovery compared to FRTPost-1) to the highest value followed by a recovery to baseline. This time point is not included in the paper by Cao et al. However, Lee et al. reported an increase at two months after FRT, which recovered at four months; this could potentially correspond to the peak we found at 101.6 days (three months) after FRT.

We did not detect any dose-response relationship, which has been described in several studies (2–4,12,19); we believe that the reason is low sensitivity and not physiological. Since edema, resection cavity, and visible tumor were excluded from the analysis, these should not confound our results. However, abnormal brain tissue that could not be visually detected still poses a problem, but probably less significant.

Moreover, concomitant and adjuvant chemotherapy were given to all patients. However, no patient received any chemotherapy at FRTPost-1. But at FRTPost-2 to FRTPost-4, a variable administration scheme was used, including three different drugs. The diversity in our data makes it hard to draw any conclusions of possible effects on Ktrans and Ve caused by chemotherapy. Furthermore, while the concept “chemobrain” is well described in the literature (18,38,39), studies, mainly on patients with breast cancer, have shown white and gray matter volume decreases and white matter microstructural changes after chemotherapy. This has mainly been reported months to years after chemotherapy which does not comply with our time frame and does not describe any vascular changes (18,38,39).

This study has some limitations. The severity of the disease significantly contributed to a high number of excluded patients and examinations due to early drop-outs and terminated examinations, which was beyond our control. We aimed to keep a consistent FRT protocol and a similar imaging time frame throughout the patient cohort. However, we are convinced that both radiation dose and timing are essential parameters to keep constant when studying radiation-induced changes. The above-mentioned limitations all contribute to noise in our data. We minimized the noise in the post-processing steps through averaging both VFA images and contrast signals as well as utilizing a high temporal resolution population-based AIF. Furthermore, detecting small parametric values is inherently difficult due to small changes in the signal. Therefore, noise makes it difficult to detect any statistically significance difference between examinations. Still, our results agree with previous publications and suggested pathogenetic theories.

Treatment improvements have moderately increased median survival time; however, treatment is still insufficient (15,40). Furthermore, the incidence of radiation-induced cognitive impairment in patients with brain tumors who have survived six months after radiotherapy is about 50–90% (1). Imaging biomarkers can help in the evaluation of normal brain tissue injury in association with improved radiotherapy techniques and in the assessment of neuroprotective therapies, overall increasing the quality of life of patients with glioblastoma with regard to both disease and treatment sequelae. DCE-MRI shows potential, and further evaluation using established consensus-based recommendations for data acquisition and post-processing is encouraged (8).

In conclusion, additional studies are needed to validate if Ktrans and Ve derived from DCE-MRI may act as potential biomarkers for acute and early-delayed radiation-induced vascular damages. No dose-response relationship was found.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Professor Elna-Marie Larsson has received speaker honoraria from Bayer AG, Berlin, Germany.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by Bayer AG, Berlin, Germany (Grant no. 15548), and the Swedish Cancer Society (Grant No. CAN 2013/673).

References

- 1.Greene-Schloesser D, Robbins ME, Peiffer AM, et al. Radiation-induced brain injury: A review. Front Oncol 2012; 2:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li YQ, Chen P, Haimovitz-Friedman A, et al. Endothelial apoptosis initiates acute blood-brain barrier disruption after ionizing radiation. Cancer Res 2003; 63:5950–5956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyubimova N, Hopewell JW. Experimental evidence to support the hypothesis that damage to vascular endothelium plays the primary role in the development of late radiation-induced CNS injury. Br J Radiol 2004; 77:488–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pena LA, Fuks Z, Kolesnick RN. Radiation-induced apoptosis of endothelial cells in the murine central nervous system: protection by fibroblast growth factor and sphingomyelinase deficiency. Cancer Res 2000; 60:321–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sundgren PC, Cao Y. Brain irradiation: effects on normal brain parenchyma and radiation injury. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2009; 19:657–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee ST, Seo Y, Bae JY, et al. Loss of pericytes in radiation necrosis after glioblastoma treatments. Mol Neurobiol 2017:4918–4926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao Y. The promise of dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging in radiation therapy. Semin Radiat Oncol 2011; 21:147–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heye AK, Culling RD, Valdes Hernandez Mdel C, et al. Assessment of blood-brain barrier disruption using dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. A systematic review. Neuroimage Clin 2014; 6:262–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tofts PS, Brix G, Buckley DL, et al. Estimating kinetic parameters from dynamic contrast-enhanced T(1)-weighted MRI of a diffusable tracer: standardized quantities and symbols. J Magn Reson Imaging 1999; 10:223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benjaminsen IC, Brurberg KG, Ruud EB, et al. Assessment of extravascular extracellular space fraction in human melanoma xenografts by DCE-MRI and kinetic modeling. Magn Reson Imaging 2008; 26:160–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mills SJ, Soh C, Rose CJ, et al. Candidate biomarkers of extravascular extracellular space: a direct comparison of apparent diffusion coefficient and dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging–derived measurement of the volume of the extravascular extracellular space in glioblastoma multiforme. Am J Neuroradiol 2010; 31:549–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao Y, Tsien CI, Sundgren PC, et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging as a biomarker for prediction of radiation-induced neurocognitive dysfunction. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15:1747–1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:987–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cuddapah VA, Robel S, Watkins S, et al. A neurocentric perspective on glioma invasion. Nat Rev Neurosci 2014; 15:455–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paw I, Carpenter RC, Watabe K, et al. Mechanisms regulating glioma invasion. Cancer Lett 2015; 362:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prust MJ, Jafari-Khouzani K, Kalpathy-Cramer J, et al. Standard chemoradiation for glioblastoma results in progressive brain volume loss. Neurology 2015; 85:683–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor LP. Comment: Chemoradiotherapy for glioblastoma patients–the double-edged sword. Neurology 2015; 85:689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krauze A, Rowe L, Camphausen K, et al. Imaging as a tool for normal tissue injury analysis in glioma. Neurooncol Open Access 2016; 1:1. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Welsh LC, Dunlop AW, McGovern T, et al. Neurocognitive function after (chemo)-radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2014; 26:765–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein S, Staring M, Murphy K, et al. elastix: a toolbox for intensity-based medical image registration. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2010; 29:196–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shamonin DP, Bron EE, Lelieveldt BP, et al. Fast parallel image registration on CPU and GPU for diagnostic classification of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neuroinform 2013; 7:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yankeelov TE, Gore JC. Dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in oncology: theory, data acquisition, analysis, and examples. Curr Med Imaging Rev 2009; 3:91–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brookes JA, Redpath TW, Gilbert FJ, et al. Accuracy of T1 measurement in dynamic contrast-enhanced breast MRI using two- and three-dimensional variable flip angle fast low-angle shot. J Magn Reson Imaging 1999; 9:163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tofts PS. Modeling tracer kinetics in dynamic Gd-DTPA MR imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 1997; 7:91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parker GJ, Roberts C, Macdonald A, et al. Experimentally-derived functional form for a population-averaged high-temporal-resolution arterial input function for dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. Magn Reson Med 2006; 56:993–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nyholm T, Berglund M, Brynolfsson P, et al. EP-1533: ICE-Studio-An Interactive visual research tool for image analysis. Radiother Oncol 2015; 115:S837. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindig T, Kotikalapudi R, Schweikardt D, et al. Evaluation of multimodal segmentation based on 3D T1-, T2- and FLAIR-weighted images - the difficulty of choosing. Neuroimage 2017; 170:210–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown WR, Thore CR, Moody DM, et al. Vascular damage after fractionated whole-brain irradiation in rats. Radiat Res 2005; 164:662–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schultheiss TE, Stephens LC. Invited review: permanent radiation myelopathy. Br J Radiol 1992; 65:737–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tofilon PJ, Fike JR. The radioresponse of the central nervous system: a dynamic process. Radiat Res 2000; 153:357–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong CS, Van der Kogel AJ. Mechanisms of radiation injury to the central nervous system: implications for neuroprotection. Mol Interv 2004; 4:273–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rahman R, Hamdan A, Zweifler R, et al. Histogram analysis of apparent diffusion coefficient within enhancing and nonenhancing tumor volumes in recurrent glioblastoma patients treated with bevacizumab. J Neurooncol 2014; 119:149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toh CH, Castillo M, Wong AM, et al. Primary cerebral lymphoma and glioblastoma multiforme: differences in diffusion characteristics evaluated with diffusion tensor imaging. Am J Neuroradiol 2008; 29:471–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karunamuni RA, White NS, McDonald CR, et al. Multi-component diffusion characterization of radiation-induced white matter damage. Med Phys 2017; 44:1747–1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagesh V, Tsien CI, Chenevert TL, et al. Radiation-induced changes in normal-appearing white matter in patients with cerebral tumors: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008; 70:1002–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fahlström M, Blomquist E, Nyholm T, et al. Perfusion magnetic resonance imaging changes in normal appearing brain tissue after radiotherapy in glioblastoma patients may confound longitudinal evaluation of treatment response. Radiol Oncol 2018; 52:143–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee MC, Cha S, Chang SM, et al. Dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion imaging of radiation effects in normal-appearing brain tissue: changes in the first-pass and recirculation phases. J Magn Reson Imaging 2005; 21:683–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hodgson KD, Hutchinson AD, Wilson CJ, et al. A meta-analysis of the effects of chemotherapy on cognition in patients with cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 2013; 39:297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaiser J, Bledowski C, Dietrich J. Neural correlates of chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment. Cortex 2014; 54:33–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xie Q, Mittal S, Berens ME. Targeting adaptive glioblastoma: an overview of proliferation and invasion. Neuro Oncol 2014; 16:1575–1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]