A transcriptomic and metabolomic map of grape berry development elucidates timing and order of the key events of the global reprogramming featuring the ripening process.

Abstract

Grapevine (Vitis vinifera) is a model for the investigation of physiological and biochemical changes during the formation and ripening of nonclimacteric fleshy fruits. However, the order and complexity of the molecular events during fruit development remain poorly understood. To identify the key molecular events controlling berry formation and ripening, we created a highly detailed transcriptomic and metabolomic map of berry development, based on samples collected every week from fruit set to maturity in two grapevine genotypes for three consecutive years, resulting in 219 samples. Major transcriptomic changes were represented by coordinated waves of gene expression associated with early development, veraison (onset of ripening)/midripening, and late-ripening and were consistent across vintages. The two genotypes were clearly distinguished by metabolite profiles and transcriptional changes occurring primarily at the veraison/midripening phase. Coexpression analysis identified a core network of transcripts as well as variations in the within-module connections representing varietal differences. By focusing on transcriptome rearrangements close to veraison, we identified two rapid and successive shared transitions involving genes whose expression profiles precisely locate the timing of the molecular reprogramming of berry development. Functional analyses of two transcription factors, markers of the first transition, suggested that they participate in a hierarchical cascade of gene activation at the onset of ripening. This study defined the initial transcriptional events that mark and trigger the onset of ripening and the molecular network that characterizes the whole process of berry development, providing a framework to model fruit development and maturation in grapevine.

Grapevine (Vitis vinifera) berries and their processed products are economically important global commodities, but the molecular complexities of berry development and ripening are not well understood. Berry development follows a double sigmoidal curve with two phases of growth separated by a lag phase (Coombe, 1992; Dokoozlian, 2000). The first growth phase is characterized by pericarp enlargement caused by cell division and elongation. The berries accumulate organic acids but little sugar, remaining green and hard. The berries also accumulate tannins, hydroxycinnamates, and phenolic precursors (Conde et al., 2007). Berry growth slows during the lag phase, marked by the transition to ripening (veraison) when the seeds are mature. The second growth phase involves further changes that make the fruit edible and attractive, promoting seed dispersal, including change in skin color, water influx, berry softening, accumulation of sugars, loss of organic acids and tannins, and synthesis of volatile aromas (Conde et al., 2007). Hormones play a central role during berry development. Ethylene and abscisic acid (ABA) induce ripening, whereas auxin indole-3-acetic acid inhibits ripening (Cawthon and Morris, 1982; Davies and Bottcher, 2009; Böttcher et al., 2010, 2013). The ripening period is regulated primarily by ABA, which accumulates at veraison (Coombe and Phillips, 1982; Agudelo-Romero et al., 2014). The increase in ABA coincides with the accumulation of anthocyanins and sugars and the up-regulation of genes associated with ripening (Gambetta et al., 2010; Koyama et al., 2010; Castellarin et al., 2011). The role of ethylene in the ripening of nonclimacteric fruits, such as grapevine berries, is less clear than in climacteric fruit maturation (Vendrell and Palomer, 1998; Davies and Bottcher, 2009). In Cabernet Sauvignon berries, ethylene peaks just before veraison (Chervin et al., 2004). Blocking ethylene accumulation results in smaller berries, lower anthocyanin levels, and greater acidity (Chervin et al., 2004), whereas exposure to ethylene increases berry size due to changes in the expression of genes controlling cell expansion and berry softening (Chervin et al., 2008).

The availability of high-throughput analytical methods and a high-quality draft of the grapevine genome sequence (Jaillon et al., 2007) has led to the characterization of berry development at the transcriptomic (Guillaumie et al., 2011; Fasoli et al., 2012; Lijavetzky et al., 2012; Dal Santo et al., 2013a, 2016b; Cramer et al., 2014; Wong et al., 2016; Zenoni et al., 2016) and metabolomic (Anesi et al., 2015; Ghan et al., 2015; Savoi et al., 2016) levels. The metabolic transition at the onset of ripening is associated with a transcriptomic shift that drives the berry into the maturation phase (Fasoli et al., 2012). Transcriptomic analysis at this transition revealed the existence of switch genes encoding key developmental regulators (Palumbo et al., 2014).

Different varieties show variety-dependent gene expression (Degu et al., 2014; Corso et al., 2015). The genetic diversity of grapevine reflects the crosses among elite cultivars during domestication, and some of the resulting varieties have become economically important on a global scale (Myles et al., 2011). The Pinot Noir and Cabernet Sauvignon varieties appear distantly related, explaining the diversity of their grapes and wines. For example, both varieties accumulate pigments but feature distinct color profiles reflecting different types of anthocyanins and associated modifications (St-Pierre and De Luca, 2000; Mattivi et al., 2006). Also, methoxypyrazines accumulate in Cabernet Sauvignon berries, whereas the Pinot Noir variety is genetically incapable of producing detectable amounts of these compounds (Dunlevy et al., 2013).

Here, we collected Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir berries from fruit set to maturity over three consecutive vintages. Transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses revealed the expression profiles of genes during berry development and the corresponding metabolomic changes. We used multivariate analysis to distinguish between shared and variety-dependent traits and weighted gene coexpression network analysis to identify genes with the same coordinated modulation in both varieties. This approach allowed us to focus on the onset of ripening, revealing the existence of key transcriptional changes and, thus, defining putative biomarkers of this critical phase of berry maturation.

RESULTS

Berry Development and Ripening

We collected berry samples from fruit set to full maturity from Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir vines grown in the same location over three consecutive vintages (Fig. 1; Supplemental Table S1; Supplemental Data Set S1). Samples were collected every 7 to 10 d using a randomized block approach to account for field variability, resulting in 219 samples. Heat accumulation (growing degree days) suggested that the 2013 and 2014 seasons were warmer than 2012 during March to August (Supplemental Fig. S1).

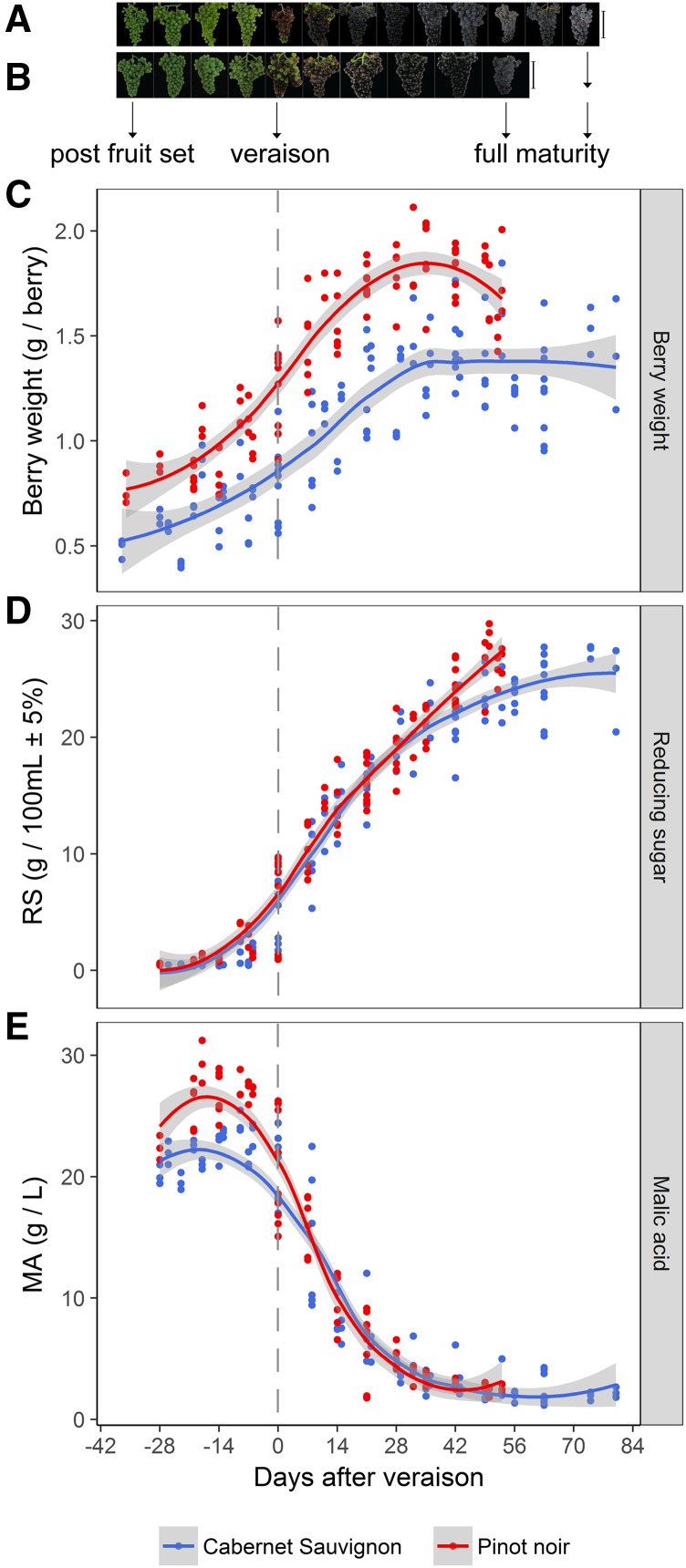

Figure 1.

Progression of grape berry ripening. A and B, Images show weekly samples depicting grape cluster development for Cabernet Sauvignon (A) and Pinot Noir (B). Bars = 10 cm. C to E, Grape berry development is shown by berry weight (C), reducing sugar (RS) accumulation (D), and malic acid (MA) accumulation (E) from fruit set to harvest. Line graphs were created using data from three vintages plotted by days after veraison. Gray shading indicates 0.95 confidence levels relative to the smoothed conditional means plotting method.

Berries from both cultivars showed similar patterns of development, as indicated by berry weight, sugar accumulation, and malic acid degradation (Fig. 1, C–E). The final weight of the Pinot Noir berries was higher than that of the Cabernet Sauvignon berries, which gained weight more slowly and reached a steady state 5 weeks after veraison (Fig. 1C). Pinot Noir berries accumulated sugar more rapidly than Cabernet Sauvignon berries (Fig. 1D), resulting in a shorter development time and an earlier harvest. The Pinot Noir berries had a higher initial malic acid content than Cabernet Sauvignon berries but featured a faster degradation until about 2 weeks after veraison, when malic acid content matched in the two varieties (Fig. 1E).

Global Metabolomic Changes during Berry Development

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis identified 526 signals across all samples, 140 of which received putative annotations, revealing components involved in amino acid, organic acid, and sugar metabolism. Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UHPLC-QTOF-MS) analysis followed by the comparison of fragmentation patterns with in-house libraries and literature data led to the putative identification of 72 metabolites, including flavan-3-ols, flavan-3-ol oligomers, phenolic acids, flavonol and dihydroflavonol glycosides, and anthocyanins (Supplemental Data Set S2).

The accumulation profile of the 212 annotated compounds was investigated by applying an unsupervised multivariate principal component analysis (PCA). In both varieties, the first 10 principal components (PCs) explained 71.6% of the variation. The first (22.3%) and third (12.9%) PCs separated the samples according to vintage, whereas PC2 (17.7%) described the distribution of samples according to time and/or development (Supplemental Fig. S2, A and B). The variety-specific metabolome was highlighted by PC4 (6%). In the PC2-PC4 plot, the separation between Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir berries became more distinct toward the final maturation stages (Fig. 2A). This resulted in three main groups of samples: preveraison berries of both varieties (Group 1), postveraison Pinot Noir berries (Group 2), and postveraison Cabernet Sauvignon berries (Group 3). Orthogonal bidirectional projections to latent structures discriminant analysis (O2PLS-DA; Trygg, 2002) confirmed the three-group distribution (Fig. 2B).

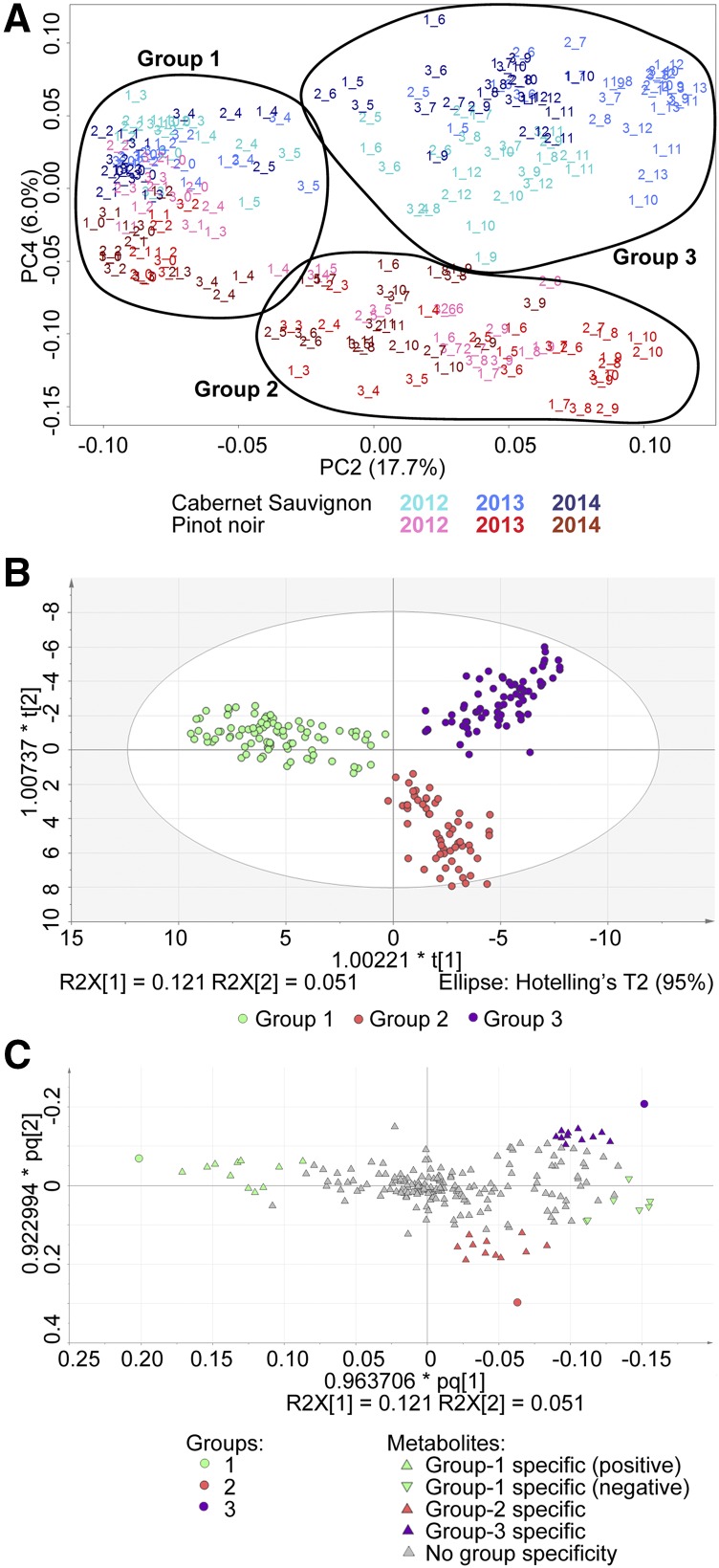

Figure 2.

PCA showing the distribution of Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir metabolites for all three vintages. A, PC2 and PC4 explain 23.7% of the variability. PC2 represents the distribution of samples according to time and/or development for both varieties. PC4 represents the distribution of samples according to variety. The early developmental time points cluster together (circled and labeled Group 1), whereas late time points reveal specific programs for either Pinot Noir or Cabernet Sauvignon berry maturation (circled and labeled Groups 2 and 3, respectively). B, O2PLS-DA distribution of the same samples verifying the three-group clustering. C, O2PLS-DA loading plot to select putative group-specific biomarkers (metabolites).

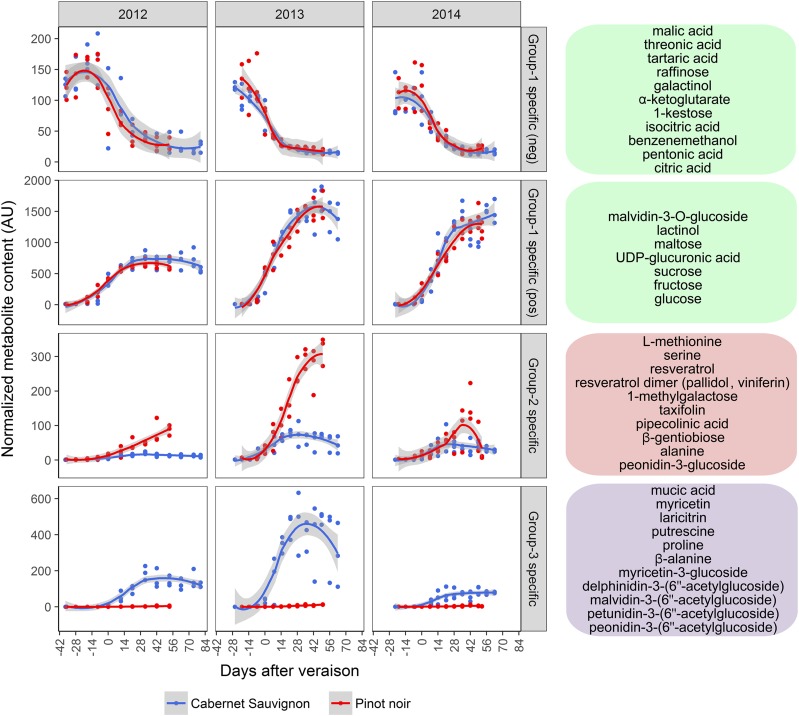

Putative metabolites specific to each group were identified in the loading plot of the three-group O2PLS-DA model (Fig. 2C). The Group 1 positively correlated metabolites comprised compounds that accumulated very early in berry development and decreased subsequently, such as organic acids and tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates (Fig. 3). The Group 1 negatively correlated metabolites began to accumulate around veraison and continued to increase throughout the remainder of ripening. These included sugars, sugar-related compounds, and malvidin 3-O-glucoside (Fig. 3). The Group 1 pattern was similar for both varieties across all three vintages. In contrast, vintage variability was observed in the metabolites in Groups 2 and 3. The general pattern for Groups 2 and 3 was accumulation starting around veraison. Group 3 metabolites were absent from Pinot Noir berries, whereas Group 2 metabolites accumulated lower levels in Cabernet Sauvignon berries but were not entirely absent (Fig. 3). Metabolites related to Pinot Noir berries (Group 2) included amino acids (l-Met, Ser, and Ala), saccharide sugars (1-methylgalactose and β-gentiobiose), stilbenes (resveratrol and the associated oligomers pallidol and viniferin), and flavonoids (taxifolin and peonidin-3-glucoside). Metabolites that were absent from Group 2 included acylated/p-coumarylated anthocyanins and 3′-hydroxylated derivatives of peonidin-3-glucoside. The metabolites specific to Cabernet Sauvignon berries (Group 3) included delphinidin-like flavonols (myricetin, myricetin-3-glucoside, and laricitrin) and acetylglucosides of anthocyanins (delphinidin, malvidin, peonidin, and petunidin). Additionally, Pro, putrescine, and mucic acid accumulated specifically in the Cabernet Sauvignon berries.

Figure 3.

Metabolite accumulation trends. Averaged metabolite accumulation profiles describe developmental groups and show distinguishable trends across fruit development, variety, and vintage. Gray shading indicates 0.95 confidence levels relative to the smoothed conditional means plotting method. Group-specific metabolites selected from the O2PLS-DA plot are reported in the schematic shown to the right of each corresponding averaged accumulation trend. Normalized metabolite content is defined by Arbitrary Unit (AU).

Global Transcriptomic Changes during Berry Development

RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) was used to monitor the expression of all grapevine genes (http://genomes.cribi.unipd.it/grape/index.php). We detected the expression of 27,320 genes (91% of the genome) in at least one of the 219 samples, and 17,720 genes (59% of the genome) showed an average expression value > 1 RPKM (reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads). A larger number of transcripts (16,768) was detected early in berry development (preveraison) compared with the maturation phase (15,028; Supplemental Fig. S3).

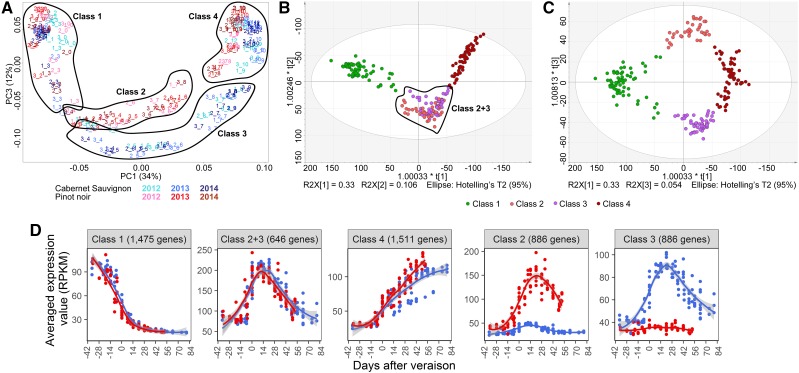

PCA was used to evaluate changes in gene expression during berry development. The first PC (33.9%) separated samples according to development and/or time for both varieties. The second PC (15.2%) separated Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir (Supplemental Fig. S4). Common and variety-specific transcriptional programs were suggested by the third PC (12.3%). The PC1-PC3 plot grouped the samples in four classes based on these common and variety-specific programs (Fig. 4A). Berry samples from both varieties clustered together at the preveraison and late maturation stages (Classes 1 and 4, respectively). Samples collected middevelopment were separated by variety, with Class 2 representing Pinot Noir and Class 3 representing Cabernet Sauvignon (Fig. 4A). The O2PLS-DA model confirmed that class distribution was influenced by development, distinguishing immature/preveraison (Class 1), middevelopment (Class 2+3), and mature (Class 4) berries (Fig. 4B), and to a lesser extent by genotype, distinguishing Pinot Noir middevelopment (Class 2) and Cabernet Sauvignon middevelopment (Class 3) berries (Fig. 4C). We selected putative class-specific genes using the loading scatterplots based on the first three O2PLS-DA components (R2X[1], R2X[2], and R2X[3]; Supplemental Fig. S5; Supplemental Data Set S3).

Figure 4.

PCA showing the distribution of gene expression in Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir berries for all three vintages. A, PC1 and PC3 explain 46.2% of the variability. PC1 represents the distribution of samples according to time and/or development for both varieties. The early and late developmental time points cluster together (circled and labeled Class 1 and Class 4, respectively). PC3 reveals the transcriptional programs of berry maturation, highlighting both universal genetic control (Classes 1 and 4) as well as varietal-specific programs (circled and labeled Class 2 and Class 3). B, O2PLS-DA distribution of the same samples to verify the four-class clustering. R2X[1] and R2X[2] show the clusters describing immature/preveraison berries (Class 1), mature berries (Class 4), and non-varietal-specific development (Classes 2+3). C, R2X[1] and R2X[3] show the clusters describing immature/preveraison berries (Class 1), mature berries (Class 4), and varietal-specific development (Pinot Noir, Class 2; Cabernet Sauvignon, Class 3). D, Averaged expression profile of the five gene classes show consistent and distinguishable trends across fruit development and variety. Line graphs were created using data from three vintages plotted by days after veraison. Gray shading indicates 0.95 confidence levels relative to the smoothed conditional means plotting method.

Class 1 Transcripts

Class 1 (early development/preveraison) represented genes strongly expressed at the earliest sampling points but rapidly down-regulated during development (Fig. 4D; Supplemental Fig. S6). Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis showed that genes in the energy metabolism category were significantly overrepresented in Class 1, including genes related to oxidative phosphorylation, carbon fixation, and photosynthesis. Genes belonging to homeostasis, transport, transcription factor activity, and genetic information processing networks also were observed (Supplemental Figs. S7 and S8A).

Class 2+3 Transcripts

Class 2+3 featured expression profiles that increased during early berry development, peaking around veraison and subsequently declining in both Pinot Noir and Cabernet Sauvignon (Fig. 4D; Supplemental Fig. S6). GO enrichment analysis showed that genes belonging to the transport, carbohydrate metabolism, and lipid metabolism categories were significantly overrepresented (Supplemental Figs. S7 and S8D). Several signal transduction components, including auxin, ethylene, and ABA signaling, and transcription factors also appeared in Class 2+3. Finally, several genes representing the phenylpropanoid pathway and flavonoid/anthocyanin biosynthesis or modification enzymes were observed.

Class 2 Transcripts

Class 2 comprised Pinot Noir-specific genes with expression profiles similar to Class 2+3 (Fig. 4D; Supplemental Fig. S6). These genes were enriched in functions related to secondary metabolism, biotic stimulus responses, and stress responses as well as transport and amino acid metabolism (Supplemental Figs. S7 and S8B).

Class 3 Transcripts

Class 3 comprised Cabernet Sauvignon-specific genes mainly representing transport and genetic information processing networks (Supplemental Figs. S7 and S8C). The transport category was significantly overrepresented, and the genetic information processing network category encompassed diverse functions representing RNA transport, synthesis, and splicing as well as protein synthesis, transport, and turnover.

Class 4 Transcripts

Class 4 was characterized primarily by genes expressed at the late-ripening stages in both varieties with increasing expression throughout development (Fig. 4D; Supplemental Fig. S6). The Class 4 genes primarily encoded transcription factors and components of the genetic information processing network. The latter included genes involved in cellular component organization, like ribosome biogenesis, and functions related to the spliceosome and nucleic acid processing, such as DNA replication, RNA transport, and degradation (Supplemental Figs. S7 and S8E).

Coexpression Network

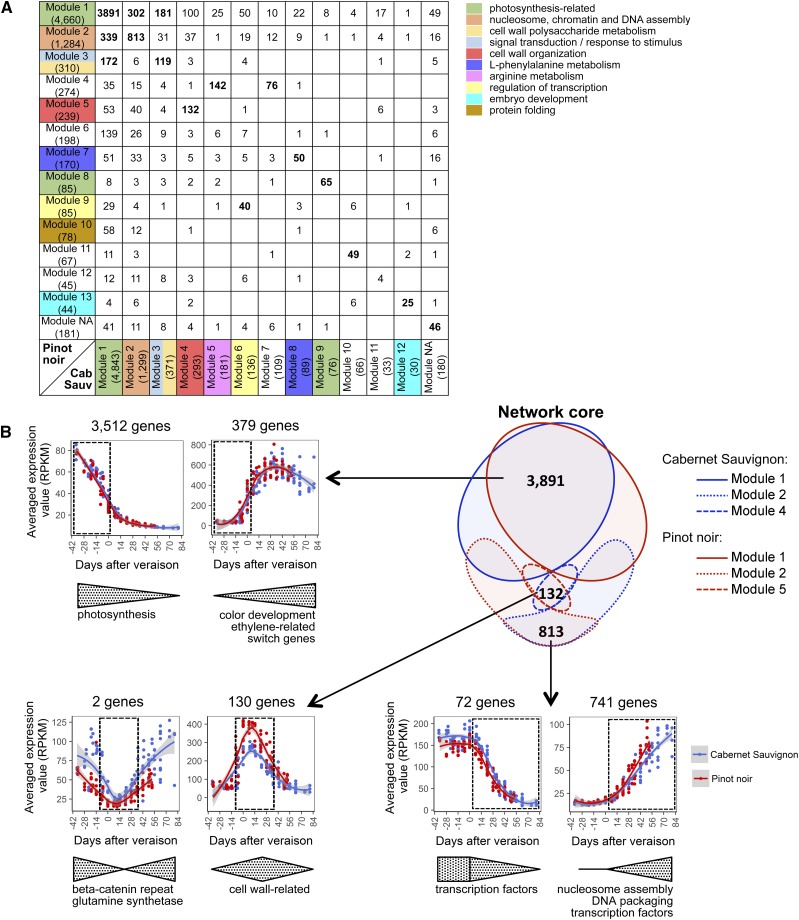

We used weighted gene coexpression network analysis (WGCNA) to define modules based on pairwise correlations between gene expression profiles, revealing 12 Cabernet Sauvignon modules and 13 Pinot Noir modules (Supplemental Data Set S4). The modules were numbered according to the number of genes assigned to each module (i.e. Module 1 was represented by the greatest number of genes, with subsequent modules including fewer genes). Most of the genes fell into the first four modules for both varieties, with Module 1 featuring 4,660 genes in Pinot Noir and 4,843 in Cabernet Sauvignon, representing more than half of all genes. Genes that did not belong to any coexpression module (181 genes in Pinot Noir and 180 in Cabernet Sauvignon) were grouped arbitrarily in Module NA (no assignment).

We compared the variety-specific networks to look for module conservation (Fig. 5A). Moreover, the expression trends of the module-specific genes revealed which genes were involved in berry development and which were potentially influenced by environmental effects (Supplemental Figs. S9 and S10). We identified four key module categories, one describing berry development (Cabernet Sauvignon Modules 1, 2, 4, and 11 [Supplemental Fig. S9, A, B, D, and K] and Pinot Noir Modules 1, 2, and 5 [Fig. 5B; Supplemental Fig. S10, A, B, and E]), another describing the interaction between development- and vintage-specific environmental conditions (Cabernet Sauvignon Modules 3, 6, and 8 [Supplemental Fig. S9, C, F, and H] and Pinot Noir Modules 3, 7, 9, and 10 [Supplemental Figs. S10, C, G, I, J, and L, and S11, A–C]), another describing exclusive and transient vintage effects (Cabernet Sauvignon Modules 5 and 7 [Supplemental Fig. S9, E and G] and Pinot Noir Module 4 [Supplemental Figs. S10D and S11D]), and the last reflecting unknown accidental events that trigger coordinated transcriptional modulation (Cabernet Sauvignon Modules 9–11 [Supplemental Fig. S9, I–K] and Pinot Noir Modules 6, 8, 11, and 13 [Supplemental Figs. S10, F, H, K, and M, and S11E]). The development-related modules represented the core coexpression network (Fig. 5B). More than 80% of Module 1 genes were conserved between Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir, and the rest were distributed among the other modules with decreasing percentage. Module 1 contained significantly enriched photosynthesis-related genes, which mainly declined during development (Fig. 5B; Supplemental Figs. S9A and S10A). However, Module 1 also contained anticorrelated profiles (709 and 727 in Pinot Noir and Cabernet Sauvignon, respectively) corresponding to transcripts that were up-regulated during ripening (Fig. 5B). Some of the 379 commonly up-regulated genes matched the Class 2+3 and Class 4 genes (Fig. 4; Supplemental Data Set S3). Anticorrelated profiles also were present in Module 2 of both cultivars (Fig. 5B; Supplemental Figs. S9B and S10B). Most of the Module 2 genes were up-regulated during development starting at veraison and were enriched in DNA packaging and chromosome organization functions, potentially reflecting the epigenetic regulation of fruit maturation (Liu et al., 2015; Gallusci et al., 2016). Anticorrelated genes (down-regulated from veraison onward) were related mainly to transcription factor activity (Fig. 5B). As highlighted in the conservation heat map (Fig. 5A), Cabernet Sauvignon Module 4 matched Pinot Noir Module 5, sharing 132 genes, representing about 50% of the genes in each module. The expression of most genes in these modules peaked around veraison, and their functions predominantly involved secondary metabolism and cell wall processes (Fig. 5B). The secondary metabolic pathways represented in Cabernet Sauvignon Module 4 covered terpenoid, ABA/carotenoid, and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Only the genes representing the ABA/carotenoid pathway also were found among the 132 genes within Pinot Noir Module 5, whereas genes related to terpenoid and phenylpropanoid metabolism fell into Module 1, suggesting different expression profiles and relationships in the network core (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Transcriptomic correlation network. A, The table shows the number of genes conserved between Pinot Noir (rows) and Cabernet Sauvignon (columns) network modules generated by WGCNA. Text in boldface indicates the most relevant shared genes in the module-by-module comparison. Module identifiers (row and column headers) are colored by enriched functional categories found in each gene network module. The total number of genes belonging to each module is indicated in parentheses. B, The Venn diagram shows the network core of genes conserved between the Pinot Noir- and Cabernet Sauvignon-associated modules. The average expression trends of the shared genes and their main functional categories are indicated by the arrows. Line graphs were created using data from three vintages plotted by days after veraison. Dotted boxes indicate the expression waves identified by the genes belonging to the modules. Gray shading indicates 0.95 confidence levels relative to the smoothed conditional means plotting method.

Markers of the Onset of Ripening

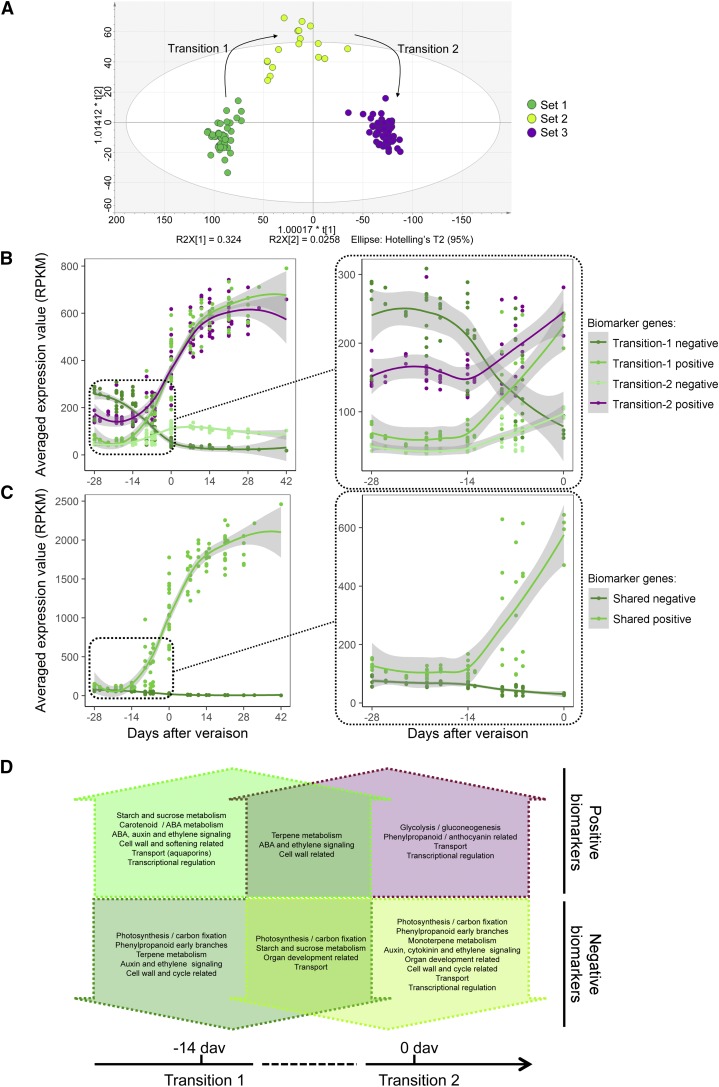

To investigate the molecular mechanisms that regulate the transition from lag phase to ripening, we analyzed samples of both cultivars around veraison. Using PCA, the remaining 126 samples were divided into three groups, defined as early veraison, midveraison, and late veraison (Supplemental Fig. S12A). Plotting these samples by sugar accumulation showed little change in reducing sugars between the early- and midveraison samples but a larger change between the midveraison and late-veraison samples (Supplemental Fig. S12B). We used O2PLS-DA to verify the three-class distribution. The early- and late-veraison samples clustered tightly, whereas the midveraison samples clustered less tightly (Fig. 6A). Therefore, veraison could be resolved into two back-to-back molecular transitions starting from 14 d before veraison (Supplemental Fig. S12B). To identify putative positive and negative molecular biomarkers of each transition, we created two distinct two-class O2PLS-DA models (transition 1 [Supplemental Fig. S12C] and transition 2 [Supplemental Fig. S12D]), generating a list of 627 molecular biomarkers, of which 81 were shared between transitions 1 and 2 (Supplemental Data Set S5).

Figure 6.

Putative biomarker genes representing the onset of ripening. A, O2PLS-DA distribution verifying the three-set clustering (labeled Set 1, Set 2, and Set 3) and the two developmental transitions during berry development. B, and C, Positive and negative putative biomarkers of each transition selected using an S-plot (Wiklund et al., 2008) within the first (positive) and the last (negative) percentiles. B, Averaged expression profiles of transition-specific putative biomarker genes shown over the whole of development (left plot) and during the preveraison phase (right plot). C, Averaged expression profiles of putative biomarker genes shared between transitions 1 and 2 shown over the whole of development (left plot) and during the preveraison phase (right plot). Line graphs were created using data from three vintages plotted by days after veraison. Gray shading indicates 0.95 confidence levels relative to the smoothed conditional means plotting method. Regression trends were generated independently for each time frame. D, Schematic showing the most relevant putative biomarker genes specific to each transition and common to both transitions.

The averaged expression profiles of the positive and negative biomarkers of both transitions (177 genes in each) were plotted against collection time (Supplemental Fig. S12E) and PC1 score values from each sample in the unsupervised PCA (Supplemental Fig. S12F). Because samples collected on the same days fell into different classes and/or exhibited different sugar concentrations (Supplemental Fig. S12B), this second representation was used to ensure that aligning transcriptionally distinct samples by collection day was not misleading.

We found that grouping biomarkers by shared profiles (39 genes with declining expression and 42 with increasing expression) or transition-specific profiles (138 genes with declining expression and 135 with increasing expression at one transition) helped distinguish the transcriptomic changes in the first and second transitions (Fig. 6, B and C). The biomarkers showed similar features in both transitions: gene up-regulation was more extreme than gene down-regulation over time, with double the average expression value (Fig. 6, B and C). Transition 1 negative biomarkers showed a very clear downward profile, whereas transition 2 negative biomarkers showed a more complex trend, with a small initial increase until veraison followed by a very slight decline thereafter. Although the positive biomarkers of transitions 1 and 2 showed similar upward expression profiles, they differed during the preveraison phase (–28 to 0 d in the veraison time frame; Fig. 6B, right). Transition 1 biomarkers started at very low expression levels, were induced 14 d before veraison, and the average expression value doubled in less than 1 week. In contrast, transition 2 biomarkers started with a higher level of expression and were up-regulated starting 14 d before veraison at a slower rate than the transition 1 positive biomarkers. The 42 commonly up-regulated biomarkers mirrored the trend of the transition 1-specific genes, whereas the 39 commonly down-regulated biomarkers remained at minimal values, with modulation 2 weeks before veraison (Fig. 6, C and D).

Functional Analysis of Key Marker Genes of the Onset of Ripening

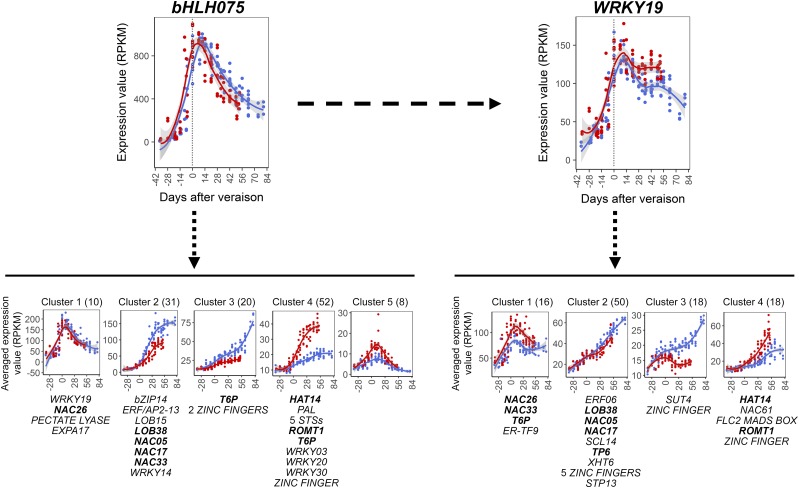

We performed functional analyses of two transcription factor genes selected among the positive biomarkers of transition 1: BASIC HELIX-LOOP-HELIX75 (VvibHLH075), the most relevant transcription factor gene as determined by correlation analysis, and WRKY19 (VviWRKY19), a biomarker of both transitions (Supplemental Data Set S5). Both genes belong to recently described grapevine gene families (Wang et al., 2014, 2018) and were identified as switch genes of the vegetative-to-mature transition in berry (Palumbo et al., 2014). The expression profiles of both genes highlighted a similar up-regulation before the onset of ripening, but WRKY19 did not decline as much as bHLH075 post veraison (Fig. 7; Supplemental Fig. S13). We identified potential targets of the transcription factors by infiltrating Thompson Seedless grapevine plantlets with Agrobacterium tumefaciens carrying overexpression constructs.

Figure 7.

bHLH075 and WRKY19 putative transcriptional activation network. Expression profiles of bHLH075 (top left) and WRKY19 (top right) point to the respective clusters of putative target genes. Averaged expression profiles of gene clusters were identified by k-means clustering analysis. The number of genes belonging to each cluster is shown in parentheses. The putative target genes belonging to carbohydrate metabolism, hormonal signaling, cell wall metabolism, secondary metabolism, and transcriptional regulation functional categories are listed below each cluster. Text in boldface indicates shared target genes between bHLH075 and WRKY19. Line graphs were created using data from three vintages plotted by days after veraison. Gray shading indicates 0.95 confidence levels relative to the smoothed conditional means plotting method. Abbreviations are as follows: ER-TF9, ETHYLENE-RESPONSIVE TF9; PAL, PHENYLALANINE AMMONIA LYASE; SCL14, SCARECROW-LIKE TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR14; STP13, SUGAR TRANSPORT PROTEIN13; STS, STILBENE SYNTHASE; T6P, TREHALOSE 6-PHOSPHATE SYNTHASE; XHT6, XYLOGLUCAN ENDOTRANSGLYCOSYLASE6.

bHLH075 overexpression identified 448 and 193 genes significantly up-regulated and down-regulated, respectively, compared with control plantlets (Supplemental Data Set S6). WRKY19 overexpression revealed the up-regulation of 261 genes and the down-regulation of 149 genes (Supplemental Data Set S7). To investigate the putative transcriptional activator role of bHLH075 and WRKY19, we focused on significantly up-regulated genes. Eighty-nine genes were up-regulated by both transcription factors. WRKY19 was found among genes up-regulated in bHLH075-overexpressing leaves.

We applied coexpression analysis to both transcriptomics data sets to define a comprehensive list of putative targets of bHLH075 and WRKY19 (Supplemental Data Sets S6 and S7). These analyses revealed 82 and 46 genes as putative targets of bHLH075 and WRKY19, respectively. The expression profiles of the putative target genes were evaluated by hierarchical clustering on the Pinot Noir and Cabernet Sauvignon berry RNA-Seq data set (Supplemental Figs. S14 and S15). This approach generated 10 clusters for bHLH075 and six clusters for WRKY19. Since we expected targets to show up-regulation through ripening, we focused on clusters 1 to 5 for bHLH075 putative targets (Supplemental Fig. S14) and on clusters 1 to 4 for WRKY19 putative targets (Supplemental Fig. S15).

bHLH075 cluster 1 targets included genes for WRKY19, transcription factor NAC26 (VviNAC26; Tello et al., 2015), a pectate lyase, EXPANSIN A17 (VviEXPA17; Dal Santo et al., 2013b), and six additional genes (Fig. 7). The average expression peaked at the onset of ripening and decreased gradually after veraison. A similar, although lower, expression profile was observed for cluster 5. Cluster 5 expression was higher in Pinot Noir than in Cabernet Sauvignon. Varietal difference also was remarked in cluster 4, which reached higher values in Pinot Noir and included 52 genes. The functions of the 52 genes were transcriptional regulation (e.g. three WRKYs, a bHLH, and the homeobox-Leu zipper protein HAT14), secondary metabolism (e.g. a Phe ammonia lyase, five stilbene synthases, and the trans-resveratrol di-O-methyltransferase ROMT1), and carbohydrate metabolism (e.g. a trehalose 6-phosphate synthase). Clusters 2 and 3 showed similar expression profiles increasing in expression after veraison, with higher expression in Cabernet Sauvignon grapes. The increase of expression was more gradual in cluster 3 compared with the rapid expression induction in cluster 2. Among the 31 genes belonging to cluster 2 were several transcription factor genes (BASIC LEUCINE ZIPPER TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR14 [bZIP14]; LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES DOMAIN15 [LOB15] and LOB38; VviNAC05, VviNAC17, and VviNAC33; and VviWRKY14) and the ethylene-responsive factor APETALA2-13 (VviAP2-13; Licausi et al., 2010). Cluster 3 (20 genes) comprised a trehalose 6-phosphate synthase and two zinc finger genes.

The WRKY19 cluster 1 (16 genes) profiles resembled those of bHLH075 cluster 1 but exhibited varietal differences (Fig. 7). This cluster was composed of ETHYLENE-RESPONSIVE FACTOR9 (ERF9), NAC26, NAC33, and the same trehalose 6-phosphate synthase found in the bHLH075 cluster 4. Cluster 2 (50 genes) exhibited a rapid upward expression trend and partially overlapped with bHLH75 cluster 2 targets (Fig. 7). Cluster 2 comprised genes for transcription factors (e.g. LOB38, NAC05, NAC17, SCARECROW-LIKE TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR14, and five zinc finger-coding genes), ERF06, carbohydrate-related and sugar signaling genes (e.g. SUGAR TRANSPORT PROTEIN13 and the same trehalose 6-phosphate synthase found in bHLH075 cluster 3), and a xyloglucan endotransglycosylase. Cluster 3 (18 genes) included SUCROSE TRANSPORTER4 (Afoufa-Bastien et al., 2010) and a zinc finger transcription factor. Cluster 4 looks like bHLH075 cluster 4 and shares seven genes, such as ROMT1 and HAT14; the other transcription factors, NAC61, FLC2 MADS box, and zinc finger, were only found to be WRKY19-specific putative targets.

Five clusters of putative target genes showed declining expression profiles over berry development (bHLH075 clusters 6, 7, and 8 and WRKY19 clusters 5 and 6; Supplemental Figs. S14 and S15). We further investigated genes included in those clusters using the Corvina expression atlas (Fasoli et al., 2012), which describes gene expression over berry development extending to postharvest ripening and in skin, pulp, and seed tissue. We also applied hierarchical clustering to the bHLH075 and WRKY19 targets using the expression profiles from the Corvina atlas. Notably, a group of genes with expression peaking at or after veraison was identified in seeds among these putative target genes showing declining expression (cluster C of bHLH075 and clusters A, B, C, and partially D of WRKY19; Supplemental Fig. S16, A and B, respectively).

DISCUSSION

The Core Set of Genes and Metabolites of Berry Development

Metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses indicated the presence of key berry developmental programs. The transcriptomic data revealed fruit development and varietal differences as the main factors describing variability among samples, with only a small vintage effect. Weather data indicated variable environmental conditions across the three growing seasons, but these had only a weak effect on the transcriptomic developmental program in our experiment. The vintage effect at the transcriptomic level was represented by the minor PCs PC4 to PC7 (Supplemental Figs. S17 and S18). In previous studies, marked differences in heat accumulation and precipitation influenced the onset and length of ripening and had a strong impact on berry development at the transcriptomic level (Dal Santo et al., 2013a). Although the vintage strongly influenced metabolite accumulation, capturing the variability of the first and third components, the consistency across vintages and varieties for Group 1 metabolites showed that primary metabolic processes, such as organic acid degradation and sugar accumulation, were not affected significantly by environment or genotype. These events appear to be driven by core transcriptional changes that are fundamental aspects of berry development.

The progress of berry development and maturation involves classes of genes with waves of specific expression during preveraison (Class 1), during veraison/midripening (Class 2+3), and during later ripening (Class 4). The downward trend of Class 1 genes demonstrates the progressive down-regulation of photosynthesis-related processes and the arrest of cell division, such that berry growth during maturation is entirely dependent on cell enlargement (Dokoozlian, 2000). The common shutdown of the transcriptional hallmarks of juvenile growth also was highlighted by the network analysis, considering the high number of down-regulated genes belonging to Module 1 shared between Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir. Interestingly, this analysis also evidenced 10-fold fewer genes commonly up-regulated along development in the two varieties belonging to the same Module 1. These represent transcripts strictly characterized by anticorrelated profiles, participating in the transcriptional shift from vegetative to mature development and playing key roles in the ripening phase (Palumbo et al., 2014).

The maturation phase featured the expression of two distinct classes of genes, one peaking near veraison (Class 2+3) and the other showing a continuous upward trend over time (Class 4). This may reflect the distinct functions of genes required to trigger the maturation phase and those required to facilitate ripening. The Class 2+3 coordinated expression wave was confirmed in Modules 4 and 5 of the Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir networks, respectively. Class 4 included genes related to sugar and ABA signaling (Gambetta et al., 2010) and known transcriptional regulators of anthocyanin biosynthesis (responsible for color development in berry skin). The R2R3-MYB anthocyanin regulator gene VviMYBA1 (and the pseudogene VviMYBA3; Kobayashi et al., 2004; Walker et al., 2007) were identified among the Class 2+3 genes, together with the LEUCOANTHOCYANIDIN DIOXYGENASE and ANTHOCYANIN O-METHYLTRANSFERASE1 (VviAOMT1), VviAOMT2, and VviAOMT3 (Muñoz et al., 2014). The gene for UDP-Glc:flavonoid-3-O-glucosyltransferase, representing a crucial step in anthocyanin biosynthesis (Boss et al., 1996a, 1996b; Kobayashi et al., 2001), was present in Class 4. The presence of known targets of MYBA transcription factors in classes with distinct average expression profiles strongly suggests that these targets are recruited by other regulators during berry development.

Interestingly, Cabernet Sauvignon Class 4 gene expression remained slightly, but significantly, lower than that of Pinot Noir beginning 2 weeks post veraison (Fig. 4D; Supplemental Fig. S6), offering a transcriptional explanation for the slower maturation of Cabernet Sauvignon berries. The upward expression profile of these genes was steeper and ultimately reached higher levels in Pinot Noir berries, which related to the earlier harvesting date. This suggests that the berry maturation rate is influenced mainly by the extent of postveraison gene up-regulation rather than by preveraison/veraison gene down-regulation.

Genotype-Dependent Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Traits during Fruit Development

The variety-specific metabolome was highlighted by the fourth PC (6%), indicating that cultivar does not explain much of the metabolomic variability. Nevertheless, the impact of variety-specific metabolomic differences on quality traits makes Pinot Noir and Cabernet Sauvignon distinct varieties (Mattivi et al., 2006). At the transcriptional level, varietal differences represented 15.2% of the variation, strongly distinguishing Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir. By O2PLS analysis, we could define two large classes of genes (Class 2 and Class 3, 886 genes each) characterized by major differential modulation occurring around veraison. These genes encompass several functions and represent a valuable source of information to explain the different physical and chemical berry traits of the two genotypes.

Most of the metabolic dissimilarities reflected the profile of phenolic compounds. Stilbenes (resveratrol and its oligomers pallidol and viniferin) were much more abundant in Pinot Noir than in Cabernet Sauvignon berries during ripening (Group 2), showing a varietal influence on the stilbenoid profile as reported previously (Degu et al., 2014; Zenoni et al., 2016). Stilbenes accumulated specifically in Pinot Noir, and variety-specific Class 2 genes included the entire stilbene synthase gene family and the transcription factors VviMYB14 and VviMYB15, which regulate the stilbene branch of the phenylpropanoid pathway (Vannozzi et al., 2012; Höll et al., 2013). These were either silent or minimally expressed in Cabernet Sauvignon (Class 2 and Class 3; Supplemental Data Set S3).

Differential hydroxylation affects the entire flavonoid pathway and leads to differences in anthocyanin accumulation and berry skin color in red-berry varieties (Mattivi et al., 2006; Falginella et al., 2010). Cabernet Sauvignon berries preferentially expressed F3′5′H genes promoting the trihydroxylation of flavonols and anthocyanins, rather than F3′H genes that promote dihydroxylation (Class 3- versus Class 2-specific genes; Supplemental Data Set S3). Hydroxylation at the 5′ position skews the anthocyanin profile toward the darker purple delphinidin-like anthocyanins, which are more stable than cyanidin-like anthocyanins, but also converts the highly bioactive compound quercetin into myricetin. The Pinot Noir and Cabernet Sauvignon metabolomes were enriched specifically for specific anthocyanin derivatives associated with the observed differences in the ratio of flavonoid-3′,5′-hydroxylase to flavonoid-3′-hydroxylase gene expression (Fig. 3; Castellarin and Di Gaspero, 2007). Cabernet Sauvignon berries have a blue skin hue compared with the redder hue of Pinot Noir berries (Mattivi et al., 2006), supporting the transcriptional mechanisms underpinning these specific varietal colors.

Acylation also contributes to the variety-specific modification of anthocyanins in red-berry varieties by increasing anthocyanin stability and solubility (Van Buren et al., 1968; Mazzuca et al., 2005). Recent studies suggest that the production of acylated anthocyanins in berries is due to the expression of Vvi3AT, encoding anthocyanin 3-O-glucoside-6′′-O-acyltransferase. The lack of acylated anthocyanins in Pinot Noir berries was strictly correlated with the absence of 3AT expression (Rinaldo et al., 2015). We found that anthocyanin acylation was another key determinant of metabolomic differences between Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir berries during maturation in that only the Cabernet Sauvignon berries accumulated anthocyanin 3-(6′′-acetyl)-glucosides. These results indicate that varietal differences in secondary metabolism reflect the genotype-dependent expression of genes.

We also found evidence that the cultivar-dependent metabolic profiles of Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir berries reflected differences in biotic and abiotic stress responses (Fig. 3). The Lys degradation product pipecolic acid accumulated in Pinot Noir berries, possibly indicating the induction of an immune response (Návarová et al., 2012). Pinot Noir berries were characterized by the pronounced expression of biotic stress response genes (Supplemental Fig. S8B), including members of the pathogenesis-related protein family (Lebel et al., 2010; Class 2, Supplemental Data Set S3). Pro, putrescine, and mucic acid accumulated specifically in Cabernet Sauvignon berries, the first two potentially reflecting an oxidative stress response (Ozden et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2013). Pro accumulates as a normal function of berry ripening (Deluc et al., 2007), but warm weather may cause hyperaccumulation (Cramer et al., 2007; Sweetman et al., 2014).

The basic events of berry maturation were conserved in the two varieties, resulting in the presence of key genes in the same coexpression modules; however, some perturbations were observed. These perturbations represent minor variations in expression among genes of the same non-variety-specific classes (Class 1, 2+3, and 4). Consequently, genes with a general similar trend are connected with diverse neighboring genes in the two networks, possibly contributing to cultivar-specific metabolic profiles. Some genes involved in the phenylpropanoid pathway were found in different coexpression modules in the networks of each variety. Examples include CHALCONE SYNTHASE3 (VviCHS3) and CHALCONE ISOMERASE1 (VviCHI1), found in Module 1 for Cabernet Sauvignon and Module 2 for Pinot Noir, and AOMT1 to AOMT3, found in Module 4 for Cabernet Sauvignon and Module 1 for Pinot Noir. Several key hexose transporters were expressed in concert with distinct modules in Pinot Noir and Cabernet Sauvignon (Supplemental Data Set S4). These observations suggest that variations in the within-module connections underlie varietal differences. Varietal differences may be responsible for traits such as ripening rate and sensitivity to environmental changes, as suggested by genes encoding ERF/AP2 family ethylene-responsive factors (Licausi et al., 2010), WRKY transcription factors (Wang et al., 2014), and the LIPOXYGENASE O (Podolyan et al., 2010) shared by Cabernet Sauvignon Module 6 and Pinot Noir Module 9.

The Pinot Noir and Cabernet Sauvignon vines used in this study were grafted on different rootstocks. Although most of the described genotype-dependent traits are determined by the scion genetic background, using different scion-rootstock combinations could have influenced the overall accumulation of secondary metabolites, as shown previously by Habran et al. (2016). We recently demonstrated that rootstock has a lower impact on berry transcriptome variability than environmental and growing parameters (Dal Santo et al., 2018). Nevertheless, the influence of different rootstocks on the genotype-specific metabolites and transcripts cannot be excluded entirely.

Putative Triggers of the Onset of Ripening

The grapevine transcriptome features a transition from immature to mature development thought to be driven by a small number of genes, as observed previously in other fleshy fruits (Karlova et al., 2014). Our data showed that the initiation of ripening entails two rapid transcriptional transitions starting 14 d before veraison describing two different gene expression behaviors rather than two temporally distinct molecular events (Fig. 6B; Supplemental Fig. S12, E and F).

Positive biomarkers of the first transition were characterized by strong induction usually followed by a decline in expression, whereas those marking the second transition were induced gradually and maintained high expression levels during ripening. This may indicate that the first set of genes trigger the expression of the second set, which, in turn, mediate the different processes that characterize ripening. Both transitions featured the shutdown of primary metabolic pathways related to vegetative growth. Genes related to carbon fixation and photosynthesis were promptly down-regulated.

Several transcripts related to hormonal signaling functions were observed among the positive and negative biomarkers, particularly those involved in auxin, ethylene, and ABA signaling. We found that three auxin-response factor genes and AUXIN/INDOLE-3-ACETIC ACID9 (IAA9) were down-regulated at the first transition and several other auxin-related factors were down-regulated at the second transition. The down-regulation of some of these genes has been reported previously (Böttcher et al., 2011; Fortes et al., 2015). Conversely, two auxin-related genes (IAA19 and SAUR29) were found among the positive biomarkers of the first and second transitions, respectively. SAUR29 has been described previously as a positive marker of the onset of ripening in grapevine (Palumbo et al., 2014; Fortes et al., 2015). Ethylene signaling genes also were found among the biomarkers of the two transitions. In particular, the negative markers included ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3, the ERF/AP2 genes VviAP2 to VviAP19, which are expressed in nonripening tissues (Licausi et al., 2010), the ERF/AP2 gene VviRAV6, and an AP2-like gene. Moreover, three ERF genes (VviERF019, ERF1, and VviERF045), described previously as switch genes during berry ripening (Palumbo et al., 2014), were identified as positive biomarkers. A recent functional analysis of VviERF045 suggested a role in epidermal patterning and the decline in photosynthetic capacity during berry ripening (Leida et al., 2016). The relationship between the modulation of these factors and the actual presence and action of ethylene remains unclear. Additionally, we identified ABA-related biomarkers involved in signal transduction rather than ABA synthesis (e.g. HVA22H, HVA22E, KEG, and ABSCISIC STRESS RIPENING PROTEIN2; Golan et al., 2014). The ABA content increases at the onset of berry ripening without the induction of ABA biosynthesis genes, suggesting that the initial increase may reflect the import of ABA from other tissues or slower turnover (Castellarin et al., 2016). The first transition included two genes representing the carotenoid pathway, namely NEOXANTHIN SYNTHASE1 and Ζ-CAROTENE DESATURASE1, suggesting that ABA may accumulate due to the abundance of carotenoid precursors.

The list of positive biomarkers of transition 1 included 17 transcription factor genes, 10 of which were identified previously as switch genes controlling the transition to berry maturation (Palumbo et al., 2014), like the HOMEOBOX-LEUCINE ZIPPER PROTEIN HB-7 (Gambetta et al., 2010), iWRKY19 (Wang et al., 2014), and the NAC transcription factors NAC17, NAC33, and NAC60 (Wang et al., 2013; Fig. 6, B and C; Supplemental Data Set S6). Some of the transcription factors were negative biomarkers of transition 1, with declining expression between early and midveraison. These included VvibZIP46, ANGUSTIFOLIA3, three zinc-finger proteins, the HOMEOBOX-LEUCINE ZIPPER PROTEIN HB13, and the MIKC-type MADS box protein VviFUL-L (Calonje et al., 2004; Carmona et al., 2008). Transition 2 featured a set of transcription factors distinct from those marking transition 1, including three zinc finger proteins and VviABF-6 with increasing expression and four zinc finger proteins, the floral homeotic protein AGAMOUS, VvibZIP23, and SQUAMOSA PROMOTER-BINDING PROTEIN11 with declining expression.

Color development was triggered at the second transition, including the induction of the anthocyanin regulator gene VviMYBA2 and several genes encoding early enzymes in the anthocyanin pathway, such as CHI1, CHS3, and CYTOCHROME B5 DIF-F. Other biomarkers included genes involved directly in anthocyanin biosynthesis, such as UDP-GLUCOSE:FLAVONOID 3-O-GLUCOSYLTRANSFERASE, genes required for anthocyanin modification and transport, such as those encoding AOMT1, GLUTATHIONE S-TRANSFERASE4, a MATE efflux family protein (VviAnthoMATE2), and the multifunctional caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase VviCCoAOMT (Giordano et al., 2016).

Several transcripts involved in the cell wall modifications associated with berry softening were identified as transition 1 positive biomarkers. The recruitment of five A-type expansins (VviEXPA1, VviEXPA5, VviEXPA14, VviEXPA18, and VviEXPA19; Dal Santo et al., 2013b) and other cell wall-modifying enzymes, such as POLYGALACTURONASE1, homologs of which are involved in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) and apple (Malus domestica) ripening (Powell et al., 2003; Atkinson et al., 2012), suggested that changes related to fruit softening were initiated as early as 14 d before veraison. The five expansins all are characterized by an expression peak during early ripening, and VviEXPA19 expression (VviExp1 in Castellarin et al., 2016) begins to increase prior to the loss of elasticity, which is regarded as one of the initial softening events. These data suggest that expansin-mediated cell wall modification may rapidly induce other major changes at the onset of ripening.

In addition to berry softening, several genes encoding transporters, channels, and pore components (e.g. transporter ABCC22, tonoplast monosaccharide transporter 2, aquaporins, and potassium transporters) were found among the biomarkers of the first transition, suggesting that the ripening-associated transport machinery is activated early to ensure efficient water and sugar uptake (Fontes et al., 2012; Cakir and Kilickaya, 2013). The gene for LIPOXYGENASE A also was identified as a marker of transition 1, supporting the role of membrane peroxidation in phase transition events (Podolyan et al., 2010; Pilati et al., 2014). The up-regulation of two alcohol dehydrogenase genes at the second transition also may be associated with the oxidative burst that occurs at the onset of berry ripening (Tesniere et al., 2004), whereas the increase in malate dehydrogenase expression may reflect the net malate degradation triggered at this stage (Sweetman et al., 2009). A thaumatin gene, encoding a grape ripening-induced protein that protects plants against changes in osmotic potential (Davies and Robinson, 2000), was found among the positive biomarkers of both transitions.

We propose that this combination of positive and negative transition biomarkers could generate a network of molecular changes characterizing the new metabolic system of the berry at ripening.

Unraveling the Transcriptional Hierarchy inside Genes Modulated at the Onset of Ripening

The functional analyses of two positive biomarkers provided the preliminary insights for disentangling the intricate transcriptional network of the onset of ripening. The analysis of bHLH075 and WRKY19 putative targets revealed an overlap of induced expression waves. Both transcriptional factors putatively induce four NAC transcription factors, NAC05, NAC26, NAC17, and NAC33 (Wang et al., 2013), the latter two of which were transition 1 positive biomarkers. NAC proteins regulate organ development in many plant species (Raman et al., 2008; Fabi et al., 2012; Hendelman et al., 2013). In tomato, NOR and NAC4 are regulators of fruit ripening (Giovannoni, 2004; Zhu et al., 2014). NAC26 was associated recently with berry size variation in grapevine (Tello et al., 2015). Interestingly, WRKY19 was found among bHLH075 putative target genes. This allows us to speculate not only that the two transcription factors act in chorus in triggering initial ripening molecular events but also that bHLH075 might work upstream of WRKY19. Although bHLH075 and WRKY19 were coexpressed, WRKY19 does not seem to induce genes encoding cell wall-modifying proteins (pectate lyase and EXPA17) that show peak expression at the onset of ripening (bHLH075 putative target genes, cluster 1). The hierarchy of the transcriptional activation might first involve bHLH075 inducing berry softening-related genes and WRKY19, in turn, amplifying the activation signal to other transcriptional regulators.

This suggests that positive markers of the first transition represent putative triggers of the onset of ripening that act through a hierarchical cascade of gene activation. Therefore, the dramatic activation of these triggers may represent the earliest events that precisely mark the onset of ripening.

CONCLUSION

The creation of a highly detailed transcriptomic and metabolomic map of grape berry development allowed us to investigate the developmental phases in unprecedented detail, elucidating the timing and order of key events of global reprogramming in the ripening process. In particular, we unraveled putative marker genes that might govern the initial transcriptional events of the onset of ripening. The application of a multiomics approach provided a valuable platform to profile the metabolomic and transcriptomic components underlying varietal difference and across vintages. This study delivers a comprehensive understanding of fruit development in grapevine, which pinpoints molecular changes that affect yield and quality and molecular factors that underlie genotype specificity and interaction with the environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Vineyard Features and Plant Material Growth Conditions

Grapevine (Vitis vinifera) Cabernet Sauvignon (clone FPS 8 grafted on 5C rootstock and planted in 1997) and Pinot Noir (clone FPS 23 grafted on Freedom rootstock and planted in 2001) were used in this study. Both varieties were grown in sandy clay loam in an east-west orientation with 10-foot row spacing and 5-foot vine spacing (Supplemental Table S1).

Transient overexpression of VviWRKY19 and VvibHLH075 was performed using Thompson Seedless grapes. In vitro stock cultures were used as source and cultivated on Hoos and Blaich medium (Blaich, 1977). Plantlets were maintained at 25°C ± 1°C under a 16-h photoperiod at 60 µmol m−2 s−1 cool-white light and subcultured by clonal propagation every 5 to 6 weeks.

Sampling Strategy

Berries were collected at 10-d intervals in 2012 and weekly in 2013 and 2014, beginning at fruit set and continuing until harvest (24.5°Brix). Veraison was defined as 50% colored berries per cluster. All samples were collected at the same time of day (8 am) in randomized block designs for each cultivar: eight-vine blocks for Pinot Noir and six-vine blocks for Cabernet Sauvignon. The block designs were replicated along three rows for each cultivar to allow the collection of biological triplicates. Therefore, we collected 219 samples in total (Supplemental Data Set S1): 120 for Cabernet Sauvignon (39, 42, and 39 during vintages 2012, 2013, and 2014, respectively) and 99 for Pinot Noir (30, 33, and 36 during vintages 2012, 2013, and 2014, respectively). Each sample replicate comprised 26 clusters of berries from each vine block.

Berry Attributes

The average weights of whole berries were determined at each time point by weighing 10 samples of 10 berries from 10 different clusters collected from each vine block. For each sample, the juice from 10 clusters was analyzed for standard berry chemical attributes: reducing sugar (Glc-Fru; UV Method; Randox) and malic acid (l-malic acid; Megazyme). Berry attributes were plotted by days after veraison using the smoothed conditional means function (level of confidence = 0.95) of the R package ggpplot2 version 2.2.1 (Wickham, 2009).

Extraction of Metabolites

Sixty berries, from six isolated clusters selected randomly from the vine blocks, were ground under liquid nitrogen. Seeds were removed before grinding. Frozen powder was divided into 100-mg aliquots for GC-MS and UHPLC-QTOF-MS analyses.

GC-MS Analysis and Data Processing

GC-MS analysis was carried out using an Agilent 6890 gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies) equipped with a Gerstel automatic liner exchange system including a multipurpose sample (MPS2) dual rail and a Gerstel CIS cold injection system with the temperature increasing from 50°C to 275°C at 12°C s−1 followed by a hold for 3 min. The injection volume was 0.5 μL at a rate of 10 μL s−1. The liner (Gerstel no. 011711-010-00) was changed after every 10 samples (Maestro1 Gerstel version 1.1.4.18). A 30-m × 0.25-mm i.d. Rtx-5Sil MS column containing 0.25-μm 95% dimethyl/5% diphenyl polysiloxane film was used with an additional 10-m integrated guard column (Restek), and 99.9999% pure helium with a built-in purifier (Airgas) was set at a constant flow rate of 1 mL min−1. The oven temperature was held constant at 50°C for 1 min, ramped at 20°C min−1 to 330°C, and held for 5 min. Samples were automatically transferred to a Pegasus IV time-of-flight mass spectrometer controlled by ChromaTOF software version 2.32 (Leco) via a transfer line held at 280°C. Electron-impact ionization (70 V) was used with an ion source temperature of 250°C. The acquisition rate was 17 spectra s−1 in the mass range 85 to 500 D. A reference library search was used to annotate the metabolites. Median scaling was used to normalize metabolite measurements across vintages: for each annotated metabolite, the abundance level in a given year was divided by the ratio of its year-specific median to the median for that metabolite across all samples in all years (Reisetter et al., 2017).

UHPLC-QTOF-MS Analysis and Data Processing

Samples were fractionated using an Agilent 1290 UHPLC-6530-QTOF device and an Agilent 1290 UHPLC-6550-QTOF device equipped with an Acquity CSH C18 2.1- × 100-mm, 1.7-μm column and an Acquity VanGuard CSH C18 1.7-μm precolumn (Waters) and were analyzed by QTOF-MS in positive and negative ion modes. Two solvents were used for separation: 100% acetonitrile in water (solvent A) and 100% isopropanol (solvent B). After injecting 1.67 μL of sample at a flow rate of 0.5 μL min−1, a solvent gradient was established from 85% to 1% solvent A in 12 min and from 15% to 99% solvent B in 12 min, followed in each case by a 3-min equilibration. The retention time, intensity, mass accuracy, and peak width of analytes were monitored and matched to a reference library. Median scaling was used to normalize metabolite measurements across vintages as above (Reisetter et al., 2017).

RNA Extraction

The same powdered samples used above for metabolomic analysis were divided into 400-mg aliquots for RNA extraction. Total RNA was isolated using the Spectrum Plant Total RNA kit (Sigma-Aldrich) following the manufacturer’s instructions with some modifications (Fasoli et al., 2012).

Total RNA was isolated from approximately 100 mg of Thompson Seedless agroinfiltrated young leaves using the Spectrum Plant Total RNA kit (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA quality and quantity were determined using a Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and a Bioanalyzer Chip RNA 7500 series II (Agilent).

Library Preparation and RNA-Seq Analysis

We prepared 219 nondirectional cDNA libraries from 2.5 μg of total RNA using the Illumina TruSeq RNA Sample preparation protocol (Illumina). Library quality was determined using the Agilent High Sensitivity DNA kit on the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, and the quantity was determined by quantitative PCR using the KAPA Library Quantification kit (Kapa Biosystems, Roche Diagnostics). Single-end reads of 100 nucleotides were obtained using an Illumina HiSeq 1000 sequencer, and sequencing data were generated using the base-calling software Illumina Casava version 1.8 (32,027,722 ± 7,628,415 per sample). The reads were aligned to the grapevine 12× reference genome PN40024 (Jaillon et al., 2007) using TopHat version 2.0.6 with default parameters (Kim et al., 2013). An average of 86.7% of reads were mapped for each sample (Supplemental Data Set S8). Mapped reads were used to reconstruct the transcripts using Cufflinks version 2.0.2 (Roberts et al., 2011) and the reference genome annotation V1 (http://genomes.cribi.unipd.it/DATA). The normalized expression of each transcript was calculated as RPKM for each sample. A filter of 1-RPKM averaged value was applied as a threshold to define gene expression (i.e. gene expression < 1 RPKM on average across the entire data set was considered very low/absent expression because 1 RPKM corresponds to approximately one transcript per cell; Mortazavi et al., 2008).

Multivariate Analysis

PCA was carried out using R Studio software (https://www.rstudio.com/), and the Spearman statistical metric was chosen to create the correlation matrix. Nonrotated components were used as the parameters. O2PLS-DA was carried out using SIMCA P+ version 12 (Umetrics; Sartorius Stedim Biotech) and used to find relationships within the transcriptomic and metabolomic data sets and to reveal the class-specific transcripts and metabolites (Zamboni et al., 2010; Fasoli et al., 2012; Dal Santo et al., 2016b).

Class-specific transcripts were selected within the fifth percentile closest to the specific class, resulting in 1,475 Class 1 genes, 886 Class 2 genes, 886 Class 3 genes, and 1,511 Class 4 genes (Supplemental Fig. S5, A and B). In the R2X[1]-R2X[2] score plot, transcripts within the fifth percentile closest to Classes 2 and 3 (886 genes) represented both common and variety-specific features at middevelopment. By subtracting 240 of the variety-specific genes (Classes 2 and 3) from that list, 646 transcripts were defined representing the midripening process of both varieties, creating Class 2+3 (Supplemental Fig. S5C). Averaged profiles were plotted by days after veraison to visualize the specific trends of the class-specific transcripts and metabolites using the smoothed conditional means function (level of confidence = 0.95) of the R package ggpplot2 version 2.2.1 (Wickham, 2009).

Putative biomarker transcripts were identified using two distinct two-class O2PLS-DA models using the observations from the midveraison set and either the early set (transition 1; Supplemental Fig. S12C) or the late set (transition 2; Supplemental Fig. S12D). An S-plot was used to select putative biomarkers within the first (positive biomarkers for one set, negative for the other) and last (vice versa) percentiles (Supplemental Data Set S5; Wiklund et al., 2008; Fasoli et al., 2012). Averaged expression profiles were plotted by collection time and by the PC1 score values shown by each sample in the unsupervised PCA to visualize the specific trends of the positive and negative biomarker genes using the smoothed conditional means function (level of confidence = 0.95) of the R package ggpplot2 version 2.2.1 (Wickham, 2009).

Functional Category Distribution and GO Enrichment Analysis

All grapevine transcripts were annotated against the V1 version of the 12× draft annotation of the grapevine genome (http://genomes.cribi.unipd.it/DATA). The VitisNet annotations were used to assign grapevine genes to functional networks and pathways (Grimplet et al., 2009). GO annotations were assigned using the BiNGO version 2.3 plug-in tool in Cytoscape (http://www.cytoscape.org/) version 2.6 with PlantGOslim categories. Overrepresented PlantGOslim categories were identified using a hypergeometric test with a significance threshold of 0.05, after Benjamini and Hochberg correction with a false discovery rate of 0.001 (Klipper-Aurbach et al., 1995). The GO enrichment analysis of the coexpression networks was performed using the R package topGO version 2.28.0 (Alexa and Rahnenfuhrer, 2010), choosing the classic algorithm option (each GO term tested independently) and the Fisher’s exact test statistics.

Gene Clustering

The hierarchical clustering analysis of the WGCNA modules was performed using the clara function of the R package cluster (Kaufman and Rousseeuw, 1990). The Euclidean metric was chosen as a distance method after the row-wise scaling of the y data sets dimension. The hierarchical clustering analysis of the putative target genes of VvibHLH075 and VviWRKY19 was performed using the hclust function of R. Nonexpressed and nonannotated genes (No hit and Unknown) were excluded. Pearson’s correlation and the complete linkage were chosen as the distance metric and the clustering method, respectively. The number of significant gene clusters was evaluated by the Within groups sum of squares using the k-means function of the R package cluster (Kaufman and Rousseeuw, 1990).

WGCNA

Coexpression network analysis was used to unravel global relationships among genes and performed using the WGCNA R package (Langfelder and Horvath, 2008). Genes with a mean expression value below 1 across the experiment were discarded. We also filtered the genes with a coefficient of variation (sd divided by the mean) < 0.5. The network analysis was performed independently for the Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir data sets. Gene modules were identified by setting the WGCNA power parameter to 7 and setting the minimum module size to 30 genes. Averaged profiles of the module-specific genes were plotted by days after veraison using the smoothed conditional means function (level of confidence = 0.95) of the R package ggpplot2 version 2.2.1 (Wickham, 2009).

Gene Cloning and Bacterial Transformation

VviWRKY19 (VIT_07s0005g01710) and VvibHLH075 (VIT_17s0000g00430) sequence (coding sequence + 3′ untranslated region) cloning was performed using the GoldenBraid 2.0 (GB 2.0) system (Sarrion-Perdigones et al., 2013). Sequences were amplified from cDNA generated from grapevine cv Corvina berry skin and pulp at veraison by PCR using Pfu DNA polymerase (Promega) and GB adapted primers (Supplemental Table S2). The sequences were cloned in a pUPD vector to be verified by sequencing. The domesticated sequences were assembled with the 35S promoter and TNos terminator in the pDGBα2 destination vector. Finally, the transcriptional units α2-35S::WRKY19::TNos and α2-35S::bHLH075::TNos were assembled with the transcriptional unit α1-35S::YFP::TNos in the pDGBΩ1 destination vector. Domestication, multipartite assembly, and binary assembly were performed using software available at https://gbcloning.upv.es/. The constructs Ω1-35S::YFP::TNos-35S::WRKY19::TNos and Ω1-35S::YFP::TNos-35S::bHLH075::TNos were transferred to Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58C1 by electroporation.

Transient Gene Expression in Grapevine Thompson Seedless Plantlets

Five milliliters of selective Luria-Bertani liquid medium was inoculated with one A. tumefaciens fresh colony. The cultures were incubated for 2 d at 28°C. Two hundred milliliters of Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with antibiotics was inoculated subsequently with 5 mL of the bacterial culture and incubated overnight at 28°C at 200 rpm. The bacteria were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in the infiltration medium (10 mm MgSO4, 10 mm MES, pH 5.5, and 100 µm acetosyringone) to a final concentration of 0.5 OD600. The bacterial suspension was then incubated at room temperature for about 3 h prior to infiltration. Agroinfiltration was conducted in nonsterile conditions. Six-week-old in vitro plantlets (seven each for gene of interest overexpression and for the control Ω1-35S::YFP) were immersed in bacterial suspension and vacuum infiltrated (90 kPa) for 2 min; then, the vacuum was quickly released to let the bacterial suspension enter the leaf tissues. The procedure was repeated twice until most leaves appeared infiltrated, and the plantlets were transferred in a growth chamber under standard growth conditions.

Expression Analyses of Thompson Seedless Leaves by Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR and Microarray

The overexpression of WRKY19 and bHLH075 in Thompson Seedless leaves was verified 7 d after A. tumefaciens-mediated infection by reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis to choose four comparable overexpressing and four comparable control lines. Two micrograms of total leaf RNA was treated with DNase I (Promega) and reverse transcribed using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). RT-qPCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) and the Mx3000P real-time PCR system (Stratagene), as described by Zenoni et al. (2010, 2011). Each expression value, relative to VvUBIQUITIN1, was determined in triplicate. The primer sequences used for RT-qPCR analysis are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

Each sample was hybridized to an Agilent custom microarray four-pack 44K format (Agilent Sure Print HD 4X44K 60-mer; G2514F-048771; Dal Santo et al., 2016a; Amato et al., 2017) and scanned using an Agilent Scanner (Agilent Technologies; G2565CA). Feature extraction was evaluated by QC report. Raw fluorescence intensities (gProcessedSignalvalues) were compared with the average negative signal (gNegCtrlAveNetSig): a gene was considered expressed if signals exceeded the threshold in at least three (out of four) replicates (control or overexpressing plantlets). Filtered signals were normalized by the 75th percentile of the overall signal intensity. Statistical analysis of the microarray data was conducted using TMeV version 4.8 (http://mev.tm4.org). Differentially modulated genes were identified by between-subjects Student’s t test (α = 0.05), assuming equal variance among samples, and then selected by fold change of greater than ±1.5.

Coexpression Analysis

The gene coexpression analysis of VvibHLH075 and VviWRKY19 against their putative targets was performed using CorTo software (http://www.usadellab.org/cms/index.php?page=corto) and Pearson’s coefficient > 0.9.

ANOVA

One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s honestly significant difference test was applied to evaluate the significance of grouping transcriptomic samples by vintage (P < 0.01; Supplemental Fig. S6), using the online tool at VassarStats: Web Site for Statistical Computation (http://vassarstats.net/anova1u.html).

Accession Numbers

The transcriptomic data have been deposited in a Minimum Information About a Microarray Experiment (MIAME)-compliant database (Gene Expression Omnibus) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information. The grapevine berry RNA-Seq data accession number is GSE98923. The reference for the microarray data is GSE113225. The SubSeries (GSE113223 and GSE113224) that are linked to GSE113225 also can be accessed through the following links: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE113223 and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE113224. The metabolomics data sets supporting this article are included within the article and its additional files (Supplemental Data Set S2).

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Weather data for the 2012, 2013, and 2014 vintages in Modesto, California.

Supplemental Figure S2. PCA showing the distribution of Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir metabolites for all three vintages.

Supplemental Figure S3. Expression of all grapevine genes detected (27,320 genes) in at least one of the 219 samples.

Supplemental Figure S4. PCA showing the distribution of all transcriptomic samples collected for Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir across three vintages.

Supplemental Figure S5. O2PLS-DA loading plots to select putative class-specific biomarkers (transcripts).

Supplemental Figure S6. Average expression profiles of the five gene classes show consistent and distinguishable trends across fruit development, variety, and vintage.

Supplemental Figure S7. Functional category distribution (GO process) of genes specific to each of the five O2PLS-DA classes.

Supplemental Figure S8. GO enrichment analysis of genes overrepresented by functional category in each of the five O2PLS-DA classes.

Supplemental Figure S9. Hierarchical clustering analysis of the WGCNA modules of the Cabernet Sauvignon network.

Supplemental Figure S10. Hierarchical clustering analyses of the WGCNA modules of the Pinot Noir network.

Supplemental Figure S11. Venn diagrams showing gene conservation among the Pinot Noir- and Cabernet Sauvignon-associated modules.

Supplemental Figure S12. Steps to the identification of putative molecular biomarkers of the onset of ripening.

Supplemental Figure S13. Expression profiles of bHLH075 and WRKY19 by variety and vintage.

Supplemental Figure S14. Hierarchical clustering analysis of the bHLH075 putative target genes in Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir berry development.

Supplemental Figure S15. Hierarchical clustering analysis of the WRKY19 putative target genes in Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir berry development.

Supplemental Figure S16. Hierarchical clustering analysis of bHLH075 and WRKY19 putative target genes in Corvina berry development.

Supplemental Figure S17. PCs of minor importance showing significant vintage effects.

Supplemental Figure S18. PCA showing the distribution of all samples collected for Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir for all three vintages.

Supplemental Table S1. Vineyard data for Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir.

Supplemental Table S2. Primer sequences used for gene cloning and RT-qPCR analyses.

Supplemental Data Set S1. Description of the berry samples used in this study.

Supplemental Data Set S2. Normalized metabolomic data.

Supplemental Data Set S3. O2PLS-DA class-specific genes.

Supplemental Data Set S4. WGCNA modules and conservation between varieties.

Supplemental Data Set S5. Putative biomarker genes of transitions 1 and 2.

Supplemental Data Set S6. List of bHLH075 putative target genes and clustering.

Supplemental Data Set S7. List of WRKY19 putative target genes and clustering.

Supplemental Data Set S8. Summary of RNA-Seq data and mapping metrics.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Viticulture Chemistry and Enology Department (E. & J. Gallo Winery) for technical assistance and support; Randall Mullen for helpful discussions; and the members of the Plant Genetics Laboratory (University of Verona) for support.

Footnotes

This work was funded by the E. & J. Gallo Winery.

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Afoufa-Bastien D, Medici A, Jeauffre J, Coutos-Thévenot P, Lemoine R, Atanassova R, Laloi M (2010) The Vitis vinifera sugar transporter gene family: phylogenetic overview and macroarray expression profiling. BMC Plant Biol 10: 245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agudelo-Romero P, Ali K, Choi YH, Sousa L, Verpoorte R, Tiburcio AF, Fortes AM (2014) Perturbation of polyamine catabolism affects grape ripening of Vitis vinifera cv. Trincadeira. Plant Physiol Biochem 74: 141–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexa A, Rahnenfuhrer J (2010) topGO: Enrichment Analysis for Gene Ontology. R package, Ed 2.18.0 [Google Scholar]

- Amato A, Cavallini E, Zenoni S, Finezzo L, Begheldo M, Ruperti B, Tornielli GB (2017) A grapevine TTG2-like WRKY transcription factor is involved in regulating vacuolar transport and flavonoid biosynthesis. Front Plant Sci 7: 1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anesi A, Stocchero M, Dal Santo S, Commisso M, Zenoni S, Ceoldo S, Tornielli GB, Siebert TE, Herderich M, Pezzotti M, et al. (2015) Towards a scientific interpretation of the terroir concept: plasticity of the grape berry metabolome. BMC Plant Biol 15: 191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]