Arabidopsis MKK6 has multiple functions in plant defense responses in addition to its role in cytokinesis.

Abstract

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) MAP KINASE (MPK) proteins can function in multiple MAP kinase cascades and physiological processes. For instance, MPK4 functions in regulating development as well as in plant defense by participating in two independent MAP kinase cascades: the MEKK1-MKK1/MKK2-MPK4 cascade promotes basal resistance against pathogens and is guarded by the NB-LRR protein SUMM2, whereas the ANPs-MKK6-MPK4 cascade plays an essential role in cytokinesis. Here, we report a novel role for MKK6 in regulating plant immune responses. We found that MKK6 functions similarly to MKK1/MKK2 and works together with MEKK1 and MPK4 to prevent autoactivation of SUMM2-mediated defense responses. Interestingly, loss of MKK6 or ANP2/ANP3 results in constitutive activation of plant defense responses. The autoimmune phenotypes of mkk6 and anp2 anp3 mutant plants can be largely suppressed by a constitutively active mpk4 mutant. Further analysis showed that the constitutive defense response in anp2 anp3 is dependent on the defense regulators PAD4 and EDS1, but not on SUMM2, suggesting that the ANP2/ANP3-MKK6-MPK4 cascade may be guarded by a TIR-NB-LRR protein. Our study shows that MKK6 has multiple functions in plant defense responses in addition to cytokinesis.

Plants have evolved different strategies to protect themselves against pathogens. PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI) acts as the frontline in the plant immune system. Pattern recognition receptors localized on the plasma membrane perceive conserved microbial components collectively known as PAMPs to activate downstream defense responses (Boller and Felix, 2009; Monaghan and Zipfel, 2012). One of the well-characterized PAMPs is bacterial flagellin (Felix et al., 1999), which is perceived by the receptor-like kinase (RLK) FLAGELLIN-SENSITIVE 2 (FLS2) (Gómez-Gómez and Boller, 2000). To subvert PTI, pathogens deliver effector proteins into plant cells. Plants have evolved resistance (R) proteins to recognize pathogen effector proteins either directly or indirectly, which leads to effector-triggered immunity (Jones and Dangl, 2006; Cui et al., 2015). Most R genes encode intracellular nucleotide-binding (NB)-Leu-rich repeat (LRR) proteins (Li et al., 2015b).

In Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), there are 20 mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), 10 MAPK kinases (MAPKKs) and about 60 predicted MAPK kinase kinases (MAPKKKs) (MAPK-Group, 2002). They work in combinations to form distinct MAP kinase cascades that play diverse roles in plant development and stress signaling (Rodriguez et al., 2010; Meng and Zhang, 2013). Several MAP kinase cascades including Yoda-MKK4/MKK5-MPK3/MPK6, MEKK1-MKK1/MKK2-MPK4 and ANPs (Arabidopsis NPR1-related protein kinases)-MKK6-MPK4 have been studied extensively.

Arabidopsis MKK4/MKK5 and MPK3/MPK6 function in regulating both development and defense against pathogens. They form a MAP kinase cascade with the MAPKKK YODA to mediate signal transduction from upstream RLKs such as ERECTA and BRI1-ASSOCIATED KINASE1 (BAK1) to the downstream transcription factors in stomata development (Bergmann and Sack, 2007; Meng et al., 2015). In response to flg22 (a conserved, 22‐amino acid peptide from bacterial flagellin, Felix et al., 1999) treatment, the MAP kinase cascade consisting of MKK4/MKK5, MPK3/MPK6, and MAPKKK3/MAPKKK5 is activated (Asai et al., 2002; Bi et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2018). This kinase cascade has been shown to play critical roles in regulating the biosynthesis of ethylene, phytoalexins, and indole glucosinolates (Liu and Zhang, 2004; Ren et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2016).

The MEKK1-MKK1/MKK2-MPK4 cascade is also activated following flg22 treatment (Gao et al., 2008; Qiu et al., 2008). Components of this kinase cascade were originally identified as negative regulators of plant immunity based on the autoimmune phenotypes of the mekk1, mkk1 mkk2, and mpk4 mutants (Petersen et al., 2000; Ichimura et al., 2006; Nakagami et al., 2006; Suarez-Rodriguez et al., 2007; Gao et al., 2008; Qiu et al., 2008). Further studies on the suppressor mutants of mkk1 mkk2 showed that autoimmunity in these mutants is caused by activation of the coiled-coil-NB-LRR protein SUMM2 (Zhang et al., 2012). The autoimmune phenotypes in the mekk1, mkk1 mkk2, and mpk4 mutants are also dependent on MEKK2 (Kong et al., 2012; Su et al., 2013), but the mechanism underlying this dependence is unclear. MPK4 was recently shown to phosphorylate the mRNA decay factor PAT1 and the receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase CALMODULIN-BINDING RECEPTOR-LIKE CYTOPLASMIC KINASE 3 (CRCK3) (Roux et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2017). Loss of CRCK3 suppresses the autoimmune phenotypes in the mekk1, mkk1 mkk2, and mpk4 mutants, whereas loss of PAT1 leads to activation SUMM2-dependent defense responses.

In the absence of SUMM2, mekk1, and mkk1 mkk2 mutant plants showed enhanced susceptibility to pathogens, suggesting that the MEKK1-MKK1/MKK2-MPK4 cascade functions in promoting basal resistance against pathogens (Zhang et al., 2012). Consistently, MPK4 is required for the expression of approximately 50% of the genes induced by flg22 (Frei dit Frey et al., 2014). MPK4 also plays a role in the negative regulation of flg22-induced gene expression through phosphorylation of the transcriptional repressor ARABIDOPSIS SH4-RELATED 3 (ASR3) (Li et al., 2015a).

From a functional yeast screen, mutations that render Arabidopsis MAPKs constitutively active have been identified (Berriri et al., 2012). The specificity toward known activators and substrates appears to be unchanged in the constitutively active MAPK (CA-MPK) mutants. CA-MPK4 transgenic plants accumulate less salicylic acid following pathogen infection and exhibit enhanced susceptibility to a number of pathogens (Berriri et al., 2012). Interestingly, immunity specified by the Toll IL-1 Receptor (TIR)-NB-LRR resistance proteins RESISTANT TO PSEUDOMONAS SYRINGAE 4 (RPS4) and RECOGNITION OF PERONOSPORA PARASITICA 4(RPP4) was also found to be compromised in CA-MPK4 transgenic plants, suggesting that constitutive activation of MPK4 inhibits resistance mediated by RPS4 and RPP4.

The Arabidopsis NPK1-related Protein kinases ANP1, ANP2, and ANP3 are three MAPKKKs closely related to NPK1, which is involved in the regulation of cytokinesis in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum; Nishihama et al., 2001). Single mutants of anp1, anp2, and anp3 appear wild type-like, whereas the anp2 anp3 double mutant displays abnormal cytokinesis (Krysan et al., 2002). The anp1 anp2 anp3 triple mutant cannot be obtained because of lethality. In Arabidopsis, MKK6 and MPK4 function downstream of ANPs to regulate cytokinesis (Beck et al., 2010; Kosetsu et al., 2010; Takahashi et al., 2010; Zeng et al., 2011). MKK6 interacted with MPK4 in a yeast two-hybrid assay and phosphorylates MPK4 in vitro (Takahashi et al., 2010). Loss of MKK6 and MPK4 leads to severe defects in cytokinesis. In this study, we report that MKK6 functions together with MEKK1 and MPK4 to prevent autoactivation of SUMM2-mediated immunity, and the ANP2/ANP3-MKK6-MPK4 cascade plays a critical role in regulating defense responses independent of SUMM2, thus establishing a novel role for MKK6 in regulating plant immune signaling.

RESULTS

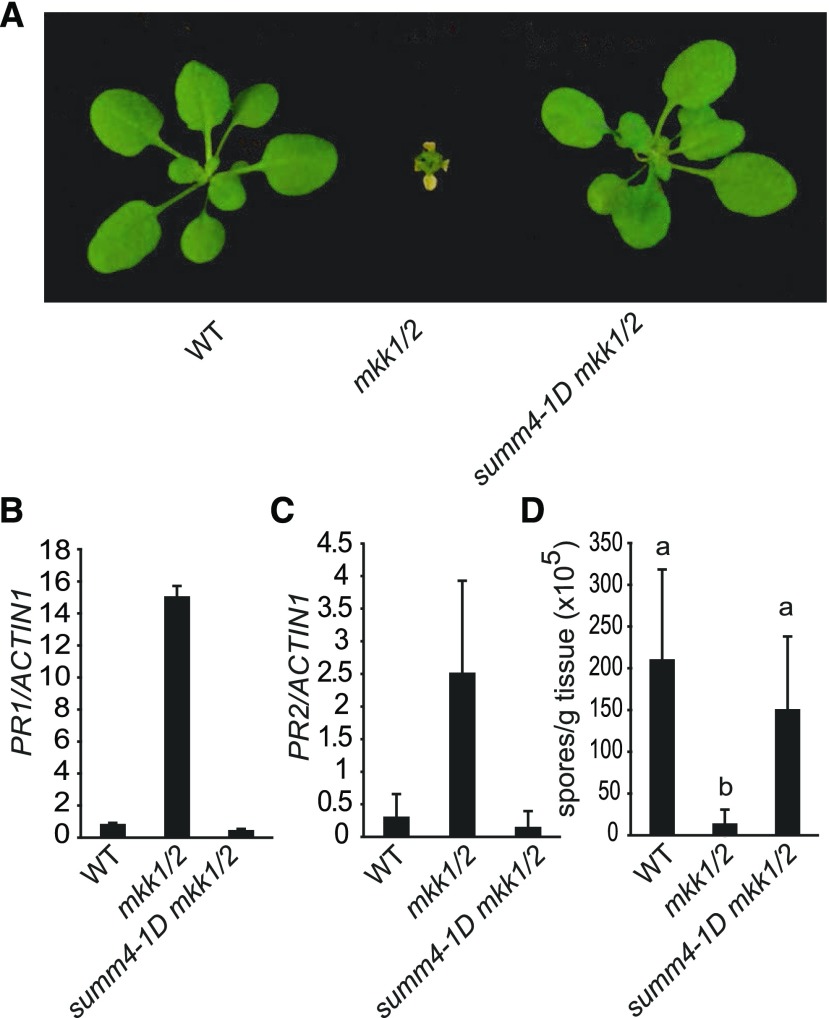

Characterization of summ4-1D mkk1 mkk2

From a previously described suppressor screen of mkk1 mkk2 (mkk1/2; Zhang et al., 2012), we identified the dominant summ4-1D mutation, which suppresses the dwarf phenotype of mkk1/2 almost completely (Fig. 1). To determine whether the constitutive defense responses in mkk1/2 are suppressed by summ4-1D, we examined the expression levels of defense marker genes PATHOGENESIS-RELATED1 (PR1) and PATHOGENESIS-RELATE 2 (PR2) in summ4-1D mkk1/2. As shown in Figure 1, B and C, constitutive expression of PR1 and PR2 in mkk1/2 is completely suppressed in the summ4-1D mkk1/2 triple mutant. We further tested whether summ4-1D affects pathogen resistance in mkk1/2 by challenging summ4-1D mkk1/2 seedlings with the oomycete pathogen Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis (H.a.) Noco2. As shown in Figure 1D, growth of H.a. Noco2 on summ4-1D mkk1/2 was much higher than on mkk1/2. Taken together, these data demonstrate that the constitutively activated defense responses in mkk1/2 are suppressed by the summ4-1D mutation.

Figure 1.

Characterization of summ4-1D mkk1/2. A, Morphological phenotypes of 3-week-old wild type (WT), mkk1/2, and summ4-1D mkk1/2. B and C, Expression levels of PR1 (B) and PR2 (C) in wild type, mkk1/2, and summ4-1D mkk1/2. Values were normalized relative to the expression of ACTIN1. Error bars represent standard deviations from three measurements. D, Growth of H.a. Noco2 on wild type, mkk1/2, and summ4-1D mkk1/2. Error bars represent standard deviations from three replicates. Statistical differences among the samples are labeled with different letters (P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA/Tukey’s test, n = 3).

Positional Cloning of SUMM4

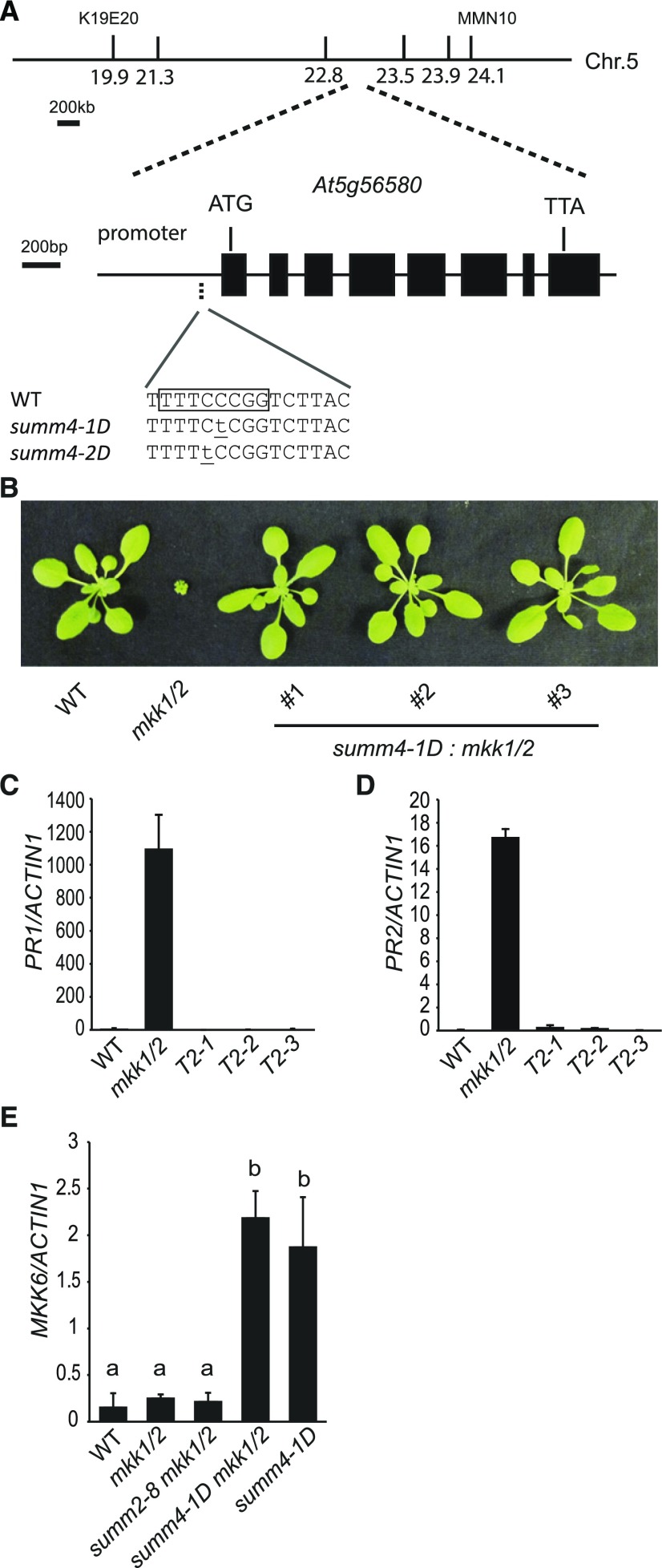

To map the summ4-1D mutation, summ4-1D mkk1/2 (in the Columbia-0 ecotype) was crossed with Landsberg erecta. Plants that were mkk1/2 homozygous in the F2 population were selected for linkage analysis. Crude mapping showed that the summ4-1D mutation is located between markers K19E20 and MMN10 on chromosome 5 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Positional Cloning of SUMM4. A, Positional cloning of SUMM4. Markers 21.3, 22.8, 23.5, and 23.9 were based on single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) between wild type (WT) and summ4-1D. The summ4 mutations are underlined. The boxed sequence is a predicted E2F binding site. B, Morphology of 3-week-old mkk1/2 plants expressing MKK6 driven by its native promoter containing the summ4-1D mutation. T2 plants of three independent transgenic lines are shown. C and D, Expression levels of PR1 (C) and PR2 (D) in wild-type, mkk1/2, and mkk1/2 transgenic lines expressing MKK6 with the summ4-1D mutation. Values were normalized relative to the expression of ACTIN1. Error bars represent standard deviations from three measurements. E, MKK6 expression levels in wild-type, mkk1/2, summ2-8 mkk1/2, summ4-1D mkk1/2, and summ4-1D plants. Values were normalized relative to the expression of ACTIN1. Error bars represent standard deviations from three repeats. Statistical differences among the samples are labeled with different letters (P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA/Tukey’s test, n = 3).

To identify the summ4-1D mutation, a genomic DNA library of summ4-1D mkk1/2 was prepared and sequenced using Illumina sequencing. Using single-nucleotide polymorphisms identified from the sequence data and progeny of F2 plants homozygous for mkk1/2 and heterozygous for summ4-1D, we further narrowed the summ4-1D mutation to a region between markers 22.8 and 23.5 on chromosome 5 (Fig. 2A). Only one mutation, a C to T substitution located 107 bp upstream of the transcription start site of MKK6 (At5g56580), was identified in this region (Fig. 2A). This mutation is within a predicted consensus binding site for E2F transcription factors (WTTSSCSS, W = A/T, S = C/G).

To test whether the mutation can suppress the mkk1/2 mutant phenotype, a genomic clone of MKK6 carrying the candidate summ4-1D mutation was transformed into plants homozygous for mkk1 and heterozygous for mkk2, as the mkk1/2 double mutant is seedling lethal. Transgenic plants homozygous for mkk1 and mkk2 were identified by PCR, and they displayed wild type-like morphology (Fig. 2B). The elevated PR gene expression levels in mkk1/2 were also suppressed in these transgenic lines (Fig. 2, C and D). These data suggest that the mutation in the promoter region of MKK6 is responsible for the suppression of the mkk1/2 mutant phenotypes in summ4-1D mkk1/2.

The summ4-1D Mutation Results in Elevated Expression of MKK6

Analysis of gene expression pattern using the eFP browser (Toufighi et al., 2005) showed that MKK6 is expressed at high levels in the shoot apex as well as at early stages of embryo development, floral development, and formation of siliques but is expressed at low levels in leaf tissue. In contrast, MEKK1 and MPK4 are both ubiquitously expressed (Supplemental Fig. S1). The expression level of MKK6 is not significantly affected by pathogen treatments, but it is rapidly induced within 1 h after flg22 treatment.

Since the summ4-1D mutation is in the promoter region of MKK6, we tested whether the expression level of MKK6 is affected. As shown in Figure 2E, the summ4-1D mkk1/2 triple mutant has much higher expression of MKK6 than wild type and mkk1/2. To make sure the increased MKK6 expression level is not caused by the suppression of the autoimmune phenotype in summ4-1D mkk1/2, we also quantified MKK6 expression level in summ2-8 mkk1/2 and found that summ2-8 does not affect the expression of MKK6 in mkk1/2. The summ4-1D single mutant has wild type-like morphology. In summ4-1D, the expression level of MKK6 is also dramatically increased compared to wild type, suggesting that the summ4-1D mutation causes increased MKK6 expression.

From the mkk1/2 suppressor screen, we also identified a second allele of summ4 designated as summ4-2D. The summ4-2D mkk1/2 mutant displayed wild-type morphology (Supplemental Fig. S2A), and the constitutive expression of PR1 and PR2 observed in mkk1/2 is largely suppressed in the triple mutant (Supplemental Fig. S2, B and C). The summ4-2D mutation was mapped to the same region as summ4-1D and found to also carry a mutation in the promoter region of MKK6 (Fig. 2A). The mutation is right next to where MKK6 is mutated in summ4-1D. In the summ4-2D mkk1/2 mutant, the expression level of MKK6 is also considerably higher than in wild type (Supplemental Fig. S2D). When a genomic clone of MKK6 carrying the summ4-2D mutation was transformed into mkk1/2, the dwarf morphology of mkk1/2 was suppressed (Supplemental Fig. S2E). Similarly, when a construct expressing MKK6 under the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter was transformed into mkk1/2, the dwarf morphology of mkk1/2 was also suppressed (Supplemental Fig. S2F). These data confirm that overexpression of MKK6 results in suppression of the mutant phenotype of mkk1/2.

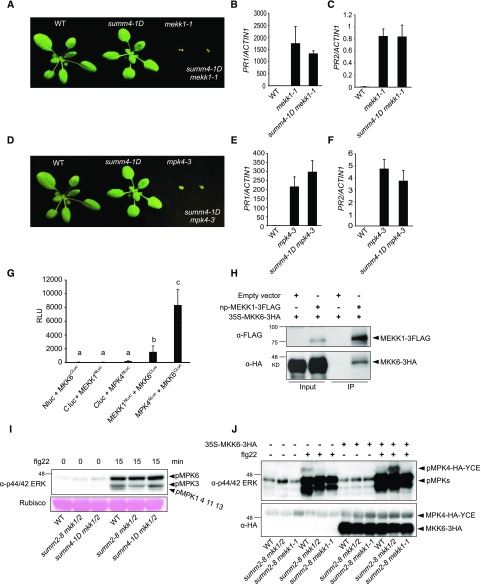

summ4-1D Does Not Suppress the Autoimmune Phenotypes of mekk1 and mpk4

Since MEKK1 functions upstream of MKK1/MKK2, we crossed summ4-1D into mekk1-1 to test whether the mekk1 mutant phenotype can be suppressed by summ4-1D. As shown in Figure 3, summ4-1D mekk1-1 has similar dwarf morphology as mekk1-1. The expression levels of PR1 and PR2 in the double mutant are also comparable to those in mekk1-1 (Fig. 3, B and C), suggesting that summ4-1D cannot suppress the constitutively induced defense responses in mekk1-1.

Figure 3.

MEKK1, MKK6, and MPK4 function in a MAPK cascade. A, Morphology of 3-week-old wild-type (WT), summ4-1D, mekk1-1, and summ4-1D mekk1-1 plants. B and C, Expression levels of PR1 (B) and PR2 (C) in wild type, mekk1-1, and summ4-1D mekk1-1. Values were normalized relative to the expression of ACTIN1. Error bars represent standard deviations from three measurements. D, Morphology of 3-week-old wild-type, summ4-1D, mpk4-3, and summ4-1D mpk4-3 plants. E and F, Expression levels of PR1 (E) and PR2 (F) in wild-type, mekk1-1, and summ4-1D mekk1-1. Values were normalized relative to the expression of ACTIN1. Error bars represent standard deviations from three measurements. G, Interactions between MKK6 and MEKK1 or MPK4. Luciferase activities from split luciferase complementation assays represented in relative light units (RLUs). Error bars represent standard deviations from eight replicates. Statistical differences among the samples are labeled with different letters (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA/Tukey’s test, n = 8). H, Analysis of the interaction between MKK6-3HA and MEKK1-3FLAG by coimmunoprecipitation. The proteins were transiently expressed in N. benthamiana using Agrobacteria strains carrying 35S-MKK6-3HA or a native promoter driven MEKK1-3FLAG (np-MEKK1-3FLAG). Immunoprecipitation was carried out using anti-FLAG beads. Western blot was carried out using anti-FLAG or anti-HA antibodies. I, MAPK activation in wild type (WT), summ2-8 mkk1/2, and summ4-1D mkk1/2. Plants were sprayed with 100 nm flg22. Samples were harvested at 0 and 15 min after flg22 treatment. MAPK activation was detected by immunoblotting with antip44/42 ERK antibody. Input was visualized by Ponceau S staining of Rubisco. J, The 35S-MPK4-HA-YCE construct was cotransfected with 35S-MKK6-3HA into protoplasts isolated from wild-type, summ2-8 mkk1/2, and summ2-8 mekk1-1. The samples were treated with or without 100 nm flg22 for 15 min before they were collected for western blot analysis using antip44/42 ERK or anti-HA antibodies.

We also generated the summ4-1D mpk4-3 double mutant to test whether the mpk4 mutant phenotype can be suppressed by summ4-1D. Morphologically, the summ4-1D mpk4-3 double mutant is indistinguishable from mpk4-3 (Fig. 3D). Analysis of the expression levels of PR1 and PR2 in summ4-1D mpk4-3 showed that they are also similar to those in mpk4-3 (Fig. 3, E and F), indicating that the autoimmune phenotypes associated with mpk4-3 cannot be suppressed by the summ4-1D mutation.

MKK6 Interacts with MEKK1 and MPK4

Previously, MKK1 and MKK2 were shown to interact with MEKK1 and MPK4 (Gao et al., 2008). To test whether MKK6 interacts with MEKK1 and MPK4, luciferase complementation assays were conducted using constructs expressing MKK6 fused to the C-terminal domain of luciferase (MKK6CLuc) and MEKK1 and MPK4 fused to the N-terminal domain of luciferase (MEKK1NLuc and MPK4NLuc) under a 35S promoter. If MKK6 associates with MEKK1 or MPK4, a functional luciferase complex would be formed. Consistent with a previous report that MPK4 interacts with MKK6 in bimolecular fluorescence complementation assays, strong luciferase activity was observed when MKK6CLuc and MPK4NLuc were coexpressed in Nicotiana benthamiana (Fig. 3G). Luciferase activity was also observed when MKK6CLuc and MEKK1NLuc were coexpressed in N. benthamiana, although at lower levels (Fig. 3G). These data suggest that MKK6 interacts with both MEKK1 and MPK4.

To further confirm the interaction between MEKK1 and MKK6, we coexpressed FLAG-tagged MEKK1 and HA-tagged MKK6 in N. benthamiana and carried out coimmunoprecipitation analysis using anti-FLAG agarose beads. As shown in Figure 3H, MKK6-3HA coimmunoprecipitated with MEKK1-3FLAG, indicating that MEKK1 and MKK6 associate with each other in vivo.

Overexpression of MKK6 Restores MAP Kinase Activation in mkk1 mkk2

To test whether the summ4-1D mutation restores MAP kinase activation in mkk1/2, we analyzed flg22-induced activation of MAP kinases in summ4-1D mkk1/2 by western blot analysis. Following flg22 treatment, three immunoreactive bands corresponding to activated MAPKs can be detected in wild-type samples. The top and middle bands represent phosphorylated MPK6 and MPK3, respectively, whereas the bottom band contains mostly phosphorylated MPK4 and a small amount of phosphorylated MPK1, MPK11, and MPK13 (Bethke et al., 2012; Nitta et al., 2014). Consistent with MKK1 and MKK2 being required for activation of MPK4 by flg22 (Gao et al., 2008; Qiu et al., 2008), there are almost no phosphorylated MPKs detected at the position of the third band in the flg22-treated summ2-8 mkk1/2 (Fig. 3I). In contrast, phosphorylated MPKs were detected at the position of the third band in the flg22-treated summ4-1D mkk1/2 (Fig. 3I), suggesting that increased expression of MKK6 leads to restoration of MPK4 activation by flg22 in summ4-1D mkk1/2.

To further confirm that overexpression of MKK6 restores flg22-induced MPK4 activation, we transformed wild-type, summ2-8 mkk1/2, and summ2-8 mekk1 protoplasts with a construct expressing MPK4 with an HA-YCE double tag as previously reported (Gao et al., 2008). The HA tag (derived from the hemagglutinin corresponding to amino acids 98–106) is about 1 kD, and the YCE (the C-terminal fragment of yellow fluorescent protein) tag is about 9.5 kD in size. Fusing MPK4 to the double tag increases the size of the protein by approximately 10.5 kD, allowing detection of phosphorylated MPK4 apart from the endogenous MAPKs with similar sizes. As shown in Figure 3J, MPK4-HA-YCE expressed in wild-type but not summ2-8 mkk1/2 or summ2-8 mekk1 protoplasts was activated upon treatment with flg22. However, when the 35S-MKK6-HA plasmid was cotransformed with the MPK4-HA-YCE construct, treatment with flg22 resulted in activation of MPK4-HA-YCE in summ2-8 mkk1/2 protoplasts. In contrast, coexpression of MKK6-HA and MPK4-HA-YCE in summ2-8 mekk1 protoplasts did not restore flg22-induced activation of MPK4-HA-YCE, suggesting that activation of MPK4 by MKK6 requires the upstream MEKK1.

PR1 and PR2 Are Constitutively Expressed in mkk6 Mutant Plants

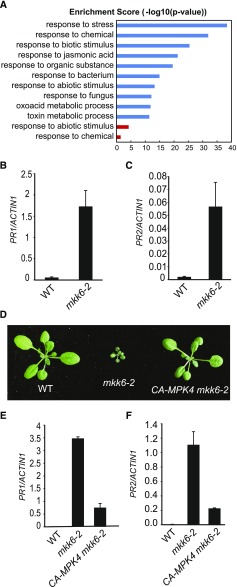

The transfer DNA (T-DNA) insertion mutants of MKK6 exhibit severe dwarf morphology (Takahashi et al., 2010). As shown by 3,3′-diaminobenzidine staining, the cotyledons of mkk6-2 accumulate high levels of H2O2 (Supplemental Fig. S3A). Microscopic cell death was also observed in the cotyledons of mkk6-2 (Supplemental Fig. S3B). To identify genes that are differentially expressed in wild-type and mkk6 loss-of-function mutant plants, we carried out RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis on wild type and mkk6-2. Six hundred fifty-seven genes showed over 2-fold increase (Supplemental Table S1), and 216 genes showed over 2-fold reduction in expression in mkk6-2 compared to wild type (Supplemental Table S2). Gene ontology (GO) analysis of the biological functions of the differentially expressed genes showed that genes responsive to biotic stress are significantly enriched (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Analysis of defense gene expression in mkk6 and CA-MPK4 mkk6-2. A, GO enrichment analysis of the biological functions of genes differentially expressed in mkk6-2 compared to wild type. The top 10 significantly enriched GO terms (determined through the PANTHER statistical overrepresentation test, P < 0.05) ranked by enrichment scores are shown. Blue bars represent significantly enriched GO terms for upregulated genes, and red bars represent significantly enriched GO terms for downregulated genes. B and C, PR1 (B) and PR2 (C) expression levels in wild type (WT) and mkk6-2. Error bars represent standard deviations from three measurements. D, Morphology of 3-week-old wild-type, mkk6-2, and CA-MPK4 mkk6-2 plants. E and F, PR1 (E) and PR2 (F) expression levels in wild-type, mkk6-2, and CA-MPK4 mkk6-2. Error bars represent standard deviations from three measurements.

Both PR1 and PR2 are among the genes up-regulated in mkk6-2. Quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis confirmed that they are constitutively expressed in mkk6-2 (Fig. 4, B and C). Similarly, mkk6-3 also has elevated PR gene expression (Supplemental Fig. S4). To determine whether constitutive activation of defense gene expression is caused by reduced MPK4 activity, we crossed mkk6-2 with a transgenic line expressing the constitutively active MPK4D198G/E202 (CA-MPK4) mutant and obtained the mkk6-2 MPK4-CA double mutant. The mkk6-2 MPK4-CA double mutant has wild-type morphology (Fig. 4D). As shown in Figure 4, E and F, constitutive expression of PR1 and PR2 in mkk6-2 is largely blocked by the MPK4-CA transgene, suggesting that MPK4 functions downstream of MKK6 in regulating plant defense responses.

Defense Responses Are Constitutively Activated in the anp2 anp3 Double Mutant

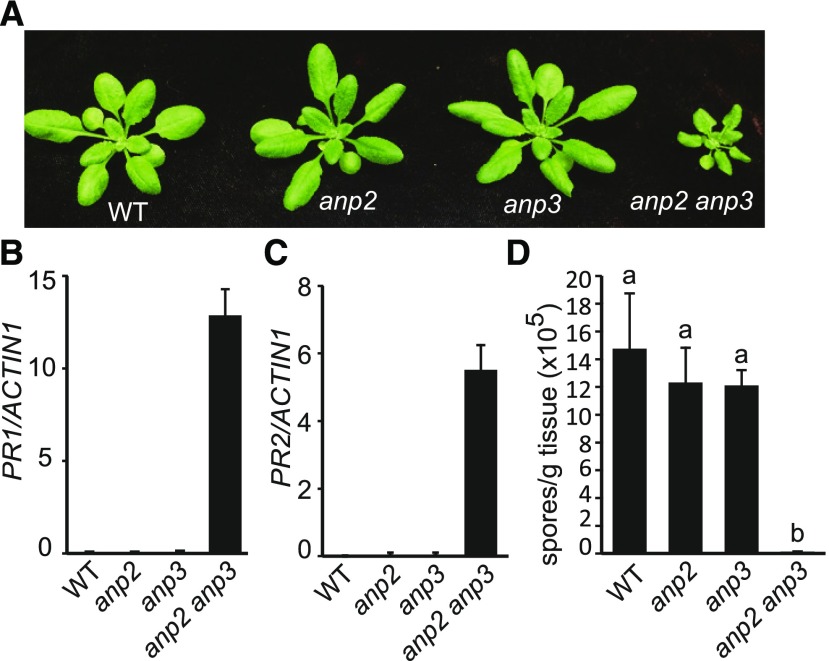

ANPs have previously been shown to interact with MKK6 and function upstream of MKK6 in regulating cytokinesis (Krysan et al., 2002; Beck et al., 2010; Kosetsu et al., 2010; Takahashi et al., 2010). Microarray analysis showed that PR1 and PR2 are up-regulated in the anp2-1 anp3-1 double mutant (Wassilewskija background; Krysan et al., 2002). According to data from the eFP browser, ANP2 is ubiquitously expressed, whereas ANP3 is expressed at high levels in the shoot apex and low levels in leaf tissue. To determine whether ANP2 and ANP3 are involved in the regulation of plant immunity, we assayed defense responses in the anp2-2 anp3-3 double mutant (Col-0 background). Compared to wild type and the anp2-2 and anp3-3 single mutants, the anp2-2 anp3-3 double mutant exhibits dwarf morphology (Fig. 5). Both PR1 and PR2 are constitutively expressed in anp2-2 anp3-3, but not in the single mutants (Fig. 5, B and C). To test whether anp2-2 anp3-3 exhibits enhanced pathogen resistance, double mutant plants were challenged with the virulent oomycete pathogen H.a. Noco2. As shown in Figure 5D, H.a. Noco2 growth is greatly reduced in anp2-2 anp3-3 compared to the wild type and the single mutants, suggesting that ANP2 and ANP3 function redundantly in regulating plant defense responses.

Figure 5.

Characterization of the anp2-2 anp3-3 double mutant. A, Morphology of 3-week-old wild-type (WT), anp2-2, anp3-3, and anp2-2 anp3-3 plants. B and C, PR1 (B) and PR2 (C) expression levels in wild-type, anp2-2, anp3-3, and anp2-2 anp3-3. Error bars represent standard deviations from three measurements. D, H.a. Noco2 growth on wild-type, anp2-2, anp3-3, and anp2-2 anp3-3. Statistical differences among the samples are labeled with different letters (P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA/Tukey’s test, n = 3).

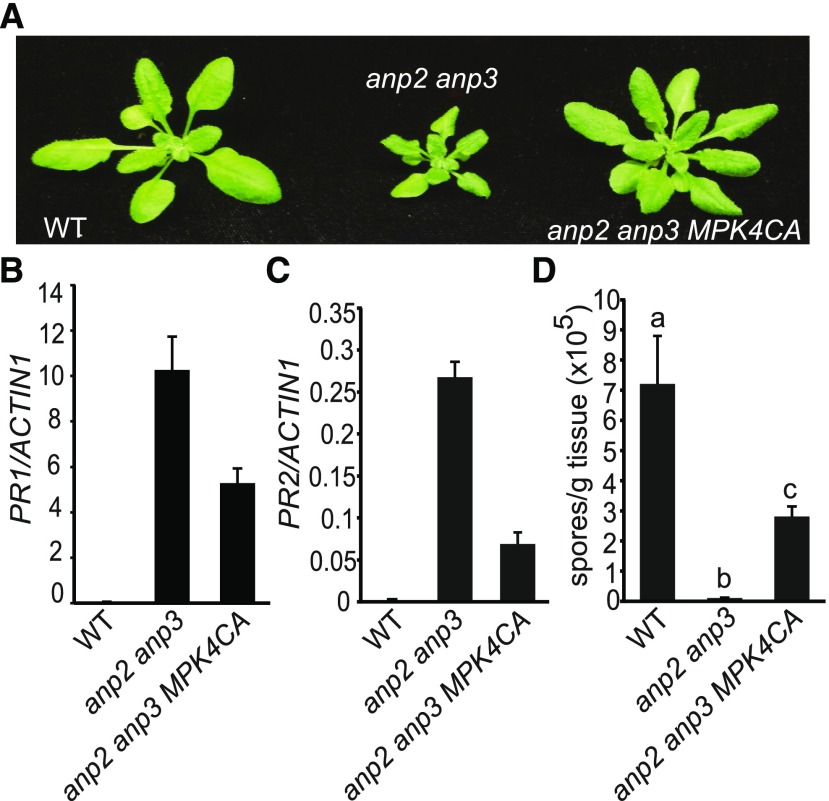

The Autoimmune Phenotype of anp2 anp3 Can Be Partially Suppressed by the CA-MPK4 Mutant

To test whether the autoimmunity observed in anp2-2 anp3-3 is due to reduced activity of MPK4, the anp2-2 anp3-3 double mutant was crossed with a transgenic line expressing the CA-MPK4 mutant to obtain the anp2 anp3 CA-MPK4 triple mutant. As shown in Figure 6, the dwarf morphology of anp2-2 anp3-3 is partially suppressed by CA-MPK4. Analysis of PR gene expression showed that the expression levels of both PR1 and PR2 are also lower in the anp2 anp3 CA-MPK4 triple mutant (Fig. 6, B and C). In addition, growth of H.a. Noco2 is much higher in the triple mutant than in the anp2-2 anp3-3 double mutant (Fig. 6D). These data suggest that ANP2/ANP3 function upstream of MPK4 in a defense-signaling pathway.

Figure 6.

CA-MPK4 partially blocks the constitutive defense responses in anp2-2 anp3-3. A, Morphology of 3-week-old wild-type (WT), anp2-2 anp3-3, and CA-MPK4 anp2-2 anp3-3 plants. B and C, PR1 (B) and PR2 (C) expression levels in wild type, anp2-2 anp3-3, and CA-MPK4 anp2-2 anp3-3. Error bars represent standard deviations from three measurements. D, H. a. Noco2 growth on wild-type, anp2-2 anp3-3, and CA-MPK4 anp2-2 anp3-3. Statistical differences among the samples are labeled with different letters (P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA/Tukey’s test, n = 3).

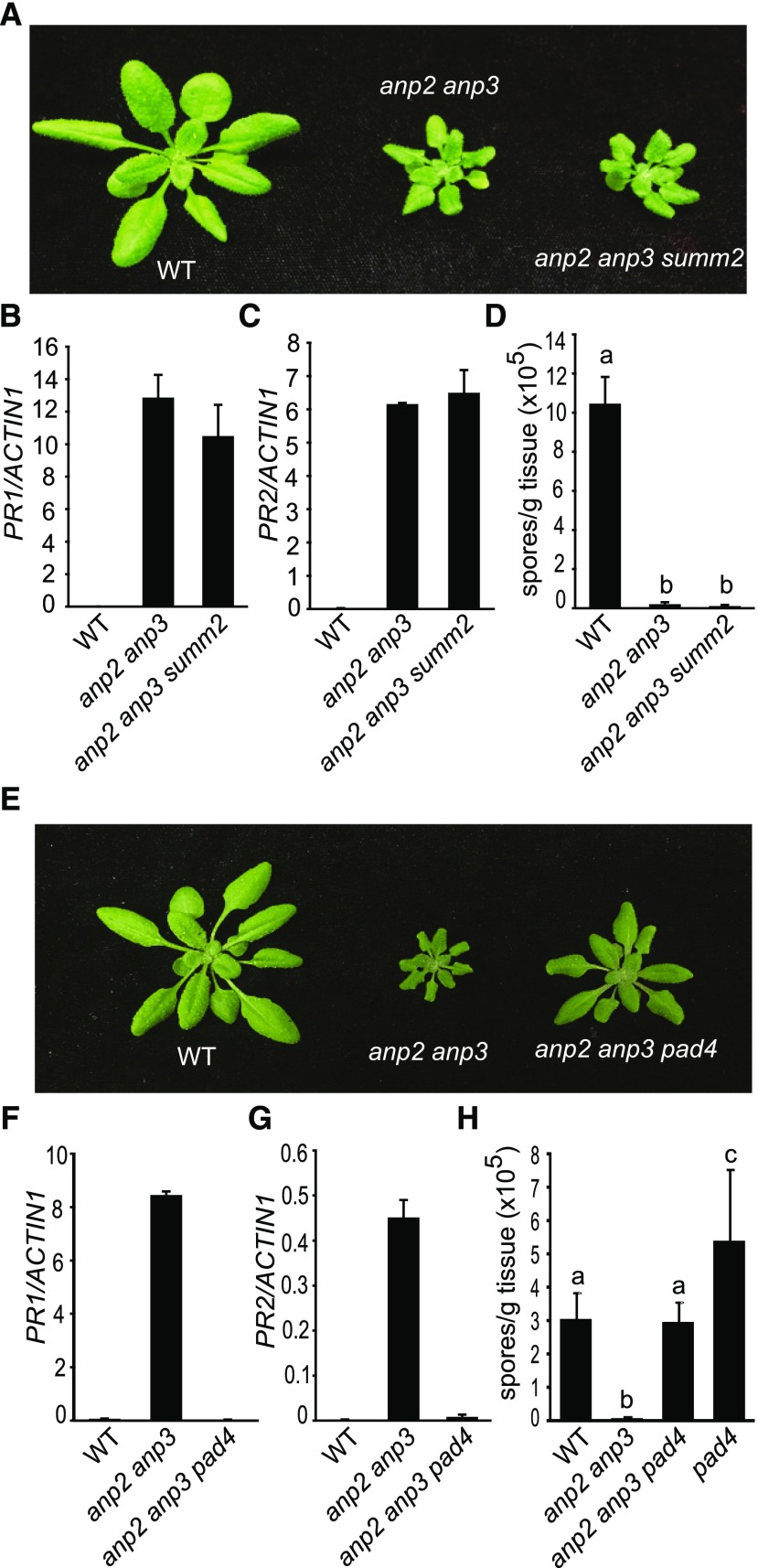

Constitutive Defense Response Activation in anp2 anp3 Is Independent of SUMM2

As constitutive defense responses in mpk4 are largely dependent on SUMM2, we tested whether the SUMM2-dependent defense pathway is activated in anp2 anp3. The anp2-2 anp3-3 summ2-8 triple mutant was obtained by crossing summ2-8 into anp2-2 anp3-3. As shown in Figure 7, summ2-8 has no effects on the morphology of anp2-2 anp3-3. It also has no effect on the expression of PR genes (Fig. 7B and Figure 7C) or resistance to H.a. Noco2 (Fig. 7D), suggesting that the autoimmune phenotype of anp2 anp3 is independent of SUMM2.

Figure 7.

Constitutive defense responses in anp2-2 anp3-3 are independent of SUMM2 but dependent on PAD4. A, Morphology of 3-week-old wild type (WT), anp2-2 anp3-3, and summ2-8 anp2-2 anp3-3. B and C, PR1 (B) and PR2 (C) expression levels in wild type, anp2-2 anp3-3, and summ2-8 anp2-2 anp3-3. D, H. a. Noco2 growth on wild type, anp2-2 anp3-3, and summ2-8 anp2-2 anp3-3. Statistical differences among the samples are labeled with different letters (P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA/Tukey’s test, n = 3). E, Morphology of 3-week-old wild-type, anp2-2 anp3-3, and pad4-1 anp2-2 anp3-3. F and G, PR1 (F) and PR2 (G) expression levels in wild type, anp2-2 anp3-3, and pad4-1 anp2-2 anp3-3. Error bars represent standard deviations from three measurements. H, H. a. Noco2 growth on wild type, anp2-2 anp3-3, and pad4-1 anp2-2 anp3-3. Statistical differences are labeled with different letters (P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA/Tukey’s test, n = 3).

PHYTOALEXIN DEFICIENT 4 (PAD4) and ENHANCED DISEASE SUSCEPTIBILITY 1 (EDS1) Are Required for the Autoimmune Phenotype of anp2 anp3

Constitutive activation of MPK4 was previously shown to compromise effector-triggered immunity specified by the TIR-NB-LRR resistance proteins RPS4 and RPP4. To test whether resistance mediated by TIR-NB-LRR proteins is activated in anp2 anp3, we crossed loss-of-function mutants of PAD4 and EDS1, which are required for resistance mediated by TIR-NB-LRR proteins (Glazebrook et al., 1996; Feys et al., 2001), into anp2-2 anp3-3. As shown in Figure 7E, the pad4-1 mutation partially suppresses the dwarf morphology of anp2-2 anp3-3. Elevated expression levels of PR1 and PR2 in anp2-2 anp3-3 are also largely suppressed in the anp2-2 anp3-3 pad4-1 triple mutant (Fig. 7, F and G). Furthermore, the enhanced resistance to H.a. Noco2 in anp2 anp3 is abolished in the anp2-2 anp3-3 pad4-1 triple mutant (Fig. 7H). Similarly, the dwarf morphology and constitutive expression of PR1 and PR2 in anp2-2 anp3-3 are also suppressed by eds1-2 (Supplemental Fig. S5). These data suggest that the autoimmune phenotype of anp2-2 anp3-3 is dependent on PAD4 and EDS1.

anp2-2 anp3-3 Is More Susceptible to Pseudomonas syringae pv. Tomato DC3000 hrcC−

To test whether PTI is affected by the loss of ANP2 and ANP3 function, the single anp2-2 and anp3-3 mutants as well as the double anp2-2 anp3-3 mutant were infiltrated with P. syringae pv. tomato (Pto) DC3000 hrcC−, a bacterial strain deficient in the delivery of type III effectors that is often used to assess PTI. As shown in Supplemental Fig. S6, growth of Pto DC3000 hrcC− is comparable in anp2-2, anp3-3, and wild type but much higher in the anp2-2 anp3-3 double mutant, suggesting that ANP2 and ANP3 function redundantly in the positive regulation of PTI.

DISCUSSION

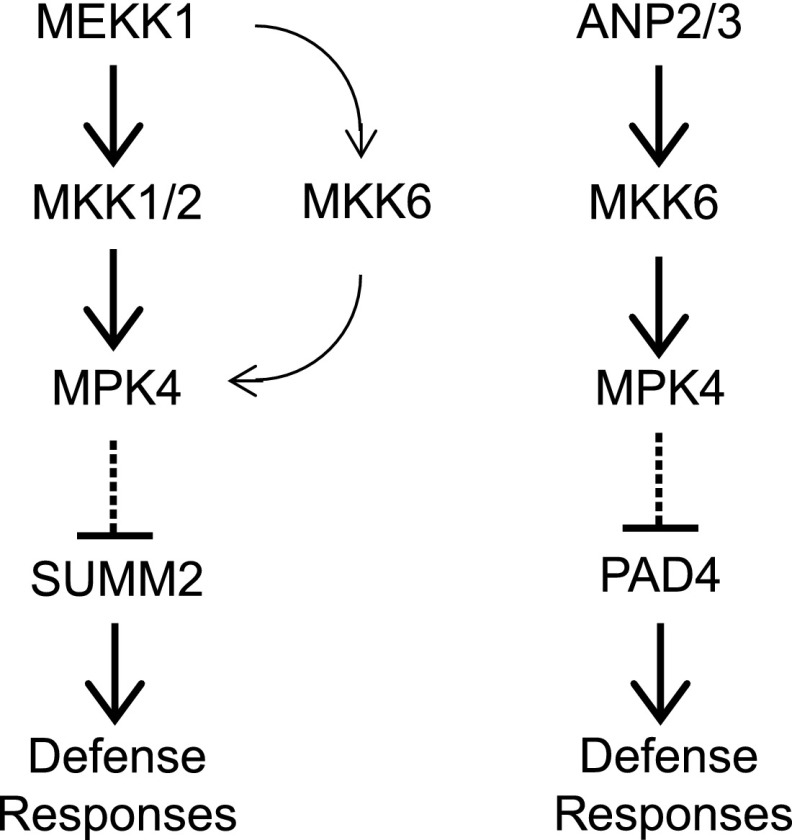

Despite the fact that MEKK1, MKK1/MKK2, and MPK4 function in the same MAP kinase pathway, mekk1 knockout mutant plants display a much more severe dwarf phenotype than mkk1/2 and mpk4 (Rodriguez et al., 2010). Loss of function of MPK11 enhances the dwarf phenotype of mpk4, suggesting that it functions redundantly with MPK4 (Bethke et al., 2012). In this study, we identified two gain-of-function summ4 mutants that suppress the autoimmune phenotypes of mkk1/2. Both mutations occur in a predicted binding site for E2F transcription factors in the promoter of MKK6 and result in increased MKK6 expression. MKK6 interacts with MEKK1 and MPK4, and elevated expression of MKK6 in the summ4 mutants suppresses the autoimmune phenotypes of mkk1/2, but not those associated with the mekk1 and mpk4 loss-of-function mutations. These data suggest that MKK6 functions in parallel with MKK1/MKK2 to transduce signals from MEKK1 to MPK4 (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

A working model for the roles of MKK6 in plant immunity. MKK6 functions in parallel with MKK1 and MKK2 to form a MAPK cascade to prevent activation of SUMM2-mediated immunity. MKK6 also functions together with ANP2/ANP3 and MPK4 in a separate MAPK cascade that inhibits a PAD4-dependent defense pathway. Arrows indicate activation and dashed lines with perpendicular lines indicate repression.

Arabidopsis ANPs and MKK6 have previously been shown to function together with MPK4 to regulate cytokinesis (Krysan et al., 2002; Beck et al., 2010; Kosetsu et al., 2010; Takahashi et al., 2010). Our data suggest that ANP2/ANP3 and MKK6 also play important roles in plant immunity. The anp2 anp3 and mkk6 mutants constitutively express PR genes and exhibit enhanced pathogen resistance. These autoimmune phenotypes can be suppressed by a constitutively active MPK4 mutant protein, suggesting that ANP2/ANP3 and MKK6 function together with MPK4 in a MAP kinases cascade that prevents autoactivation of plant defense (Fig. 8).

Arabidopsis has 60 predicted MAPKKKs, but only 10 MKKs and 20 MAPKs (MAPK-Group, 2002), suggesting that some of the MKKs and MAPKs may have multiple functions and can form distinct MAP kinase cascades with different MAPKKKs to regulate different biological processes. This is supported by the diverse roles of MKK4/MKK5 and MPK3/MPK6 in plant defense as well as in development (Meng and Zhang, 2013). Our study revealed that MKK6 also has multiple functions. In addition to its role in cytokinesis, MKK6 is involved in two MAPK kinase cascades important to plant immunity.

Both the MEKK1-MKK1/MKK2-MPK4 and ANPs-MKK6-MPK4 cascades lead to activation of MPK4. Mutations in summ2 suppress the autoimmune phenotypes of mekk1 and mkk1 mkk2, but not anp2 anp3, suggesting that these two MAP kinase cascades function independently in the regulation of plant immunity (Fig. 8). This is consistent with the observation that the mutant phenotypes of mekk1 and mkk1 mkk2 are completely dependent on SUMM2, whereas the constitutive defense responses in mpk4 can only be partially blocked by mutations in summ2 (Zhang et al., 2012). It is unclear why two kinase cascades both leading to activation of MPK4 cannot compensate each other. Previously, it was shown that MEKK1 interacts with MKK1 and MKK2 on the plasma membrane (Gao et al., 2008), whereas the ANPs-MKK6-MPK4 cascade functions in regulating cytokinesis in the nucleus (Beck et al., 2010; Kosetsu et al., 2010; Takahashi et al., 2010; Zeng et al., 2011). It is possible that the MEKK1-MKK1/MKK2-MPK4 and ANPs-MKK6-MPK4 cascades are active in different subcellular localizations to prevent constitutive activation of immune responses.

The mechanism of how the ANP2/ANP3-MKK6-MPK4 cascade regulates plant immunity is unknown. Previously, it was shown that expression of a constitutively active MPK4 leads to compromised pathogen resistance mediated by TIR-NB-LRR proteins (Berriri et al., 2012). The autoimmune phenotype of anp2 anp3 is dependent on PAD4 and EDS1, which are critical positive regulators of TIR-NB-LRR protein-mediated resistance (Glazebrook et al., 1996; Feys et al., 2001). It is likely that activation of MPK4 through the ANP2/ANP3-MKK6-MPK4 cascade is required for its functions in regulation of immunity mediated by one or more TIR-NB-LRR proteins.

Meanwhile, ANPs have been shown to function as positive regulators of elicitor-triggered defense responses and protection against the necrotrophic fungus Botrytis cinerea (Savatin et al., 2014). Increased growth of Pto DC3000 hrcC− in the anp2-2 anp3-3 double mutant also supports a positive role of ANP2 and ANP3 in PTI. It is likely that components of the ANP2/ANP3-MKK6-MPK4 cascade are targeted by certain pathogens and plants have evolved resistance proteins to sense disruption of this kinase cascade. Similar to protection of the MEKK1-MKK1/ MKK2-MPK4 cascade by the NB-LRR protein SUMM2 (Zhang et al., 2012), loss of function of ANP2/ANP3, MKK6, or MPK4 likely results in activation of immunity mediated by as-yet-unknown resistance proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials

The summ4-1D mkk1/2 triple mutant was isolated from an ethylmethanesulfonate (EMS) mutagenized M2 population of mkk1/2 (Zhang et al., 2012). The mkk1/2, mpk4-3, mekk1-1, summ2-8, summ2-8 mkk1/2, mkk6-2, mkk6-3, and pad4-1 mutants and CA-MPK4 transgenic line were described previously (Glazebrook et al., 1996; Ichimura et al., 2006; Nakagami et al., 2006; Gao et al., 2008; Takahashi et al., 2010; Berriri et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012). The summ4-1D single mutant was isolated through backcrossing the triple mutant summ4-1D mkk1/2 to wild-type Col-0 plants. The summ4-1D mekk1-1 double mutant was obtained by crossing summ4-1D mkk1/2 with mekk1-1. The summ4-1D mpk4-3 double mutant was obtained by crossing summ4-1D mkk1/2 with mpk4-3. The anp2-2 anp3-3 double mutant was obtained by crossing anp2-2 (Salk_144973) and anp3-3 (Salk_081990) obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center. The anp2-2 anp3-3 CA-MPK4, anp2-2 anp3-3 summ2-8, and anp2-2 anp3-3 pad4-1 triple mutants were obtained by crossing anp2-2 anp3-3 with CA-MPK4CA, summ2-8, and pad4-1, respectively. Plants were grown at 23°C under 16 h light/8 h dark on soil or 1/2 Murashige and Skoog (MS) media (Murashige and Skoog, 1962).

Mutant Characterization

To determine gene expression levels, RNA was extracted from 2-week-old seedlings grown on 1/2 MS media using the EZ-10 Spin Column Plant RNA Mini-Preps Kit (Bio Basic). Each sample consists of RNA from about six seedlings. Genomic DNA contamination was removed by treatment with RQ1 RNase-Free DNase (Promega). Reverse transcription was carried out using M-MuLV reverse transcriptase (New England Biolabs). RT-qPCR was performed using SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Takara). Each experiment was repeated three times with independently grown plants. Primers of PR1, PR2, and ACTIN1 used for RT-qPCR were previously described (Sun et al., 2015). Primers used for MKK6 expression are listed in Supplemental Table S3.

RNA-seq analysis was carried out using services provided by Beijing Genomics Institute. Three independent RNA samples from each genotype were mixed prior to library preparation and used for library preparation and sequencing. An average of ∼23 million raw RNA-seq reads were checked for quality and filtered for low-quality reads, adapter sequences, and contamination. The clean reads of each sample were aligned to the publicly available reference genome of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; TAIR10) using HISAT (Hierarchical Indexing for Spliced Alignment of Transcripts)(Kim et al., 2015). Gene expression levels were quantified for each gene using the RSEM software package (Li and Dewey, 2011). Differentially expressed genes were determined through the NOISeq method (Tarazona et al., 2011). GO analysis was completed using the statistical enrichment test from the PANTHER classification system (Thomas et al., 2003). The RNA-seq experiment was repeated twice.

Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis (H. a.) Noco2 infection was performed on 2-week-old seedlings. The seedlings were sprayed with spore suspensions at a concentration of 50,000 spores per mL water. The plants were covered with a clear dome and kept at 18°C under 12-h light/12-h dark cycles in a growth chamber. Samples were collected 7 d later, and spores on the plants were resuspended in water and counted using a hemocytometer. Infection results were scored as previously described (Bi et al., 2010). Each infection experiment was repeated at least twice. 3,3′-diaminobenzidine staining and trypan blue staining were performed on 2-week-old seedlings according to previously described procedures (Parker et al., 1996; Thordal-Christensen et al., 1997).

Map-Based Cloning of SUMM4

For crude mapping of summ4-1D, the summ4-1D mkk1/2 triple mutant was crossed with Landsberg erecta. F2 plants homozygous for mkk1/2 were selected for linkage analysis. summ4-1D mkk1/2 was also crossed with wild-type Col-0 plants to obtain the summ4-1D single mutant. Plants homozygous for mkk1/2 and heterozygous for summ4-1D were also identified in the F2 generation, and their progeny were used for fine mapping of summ4-1D. Markers for fine mapping were designed based on single nucleotide polymorphisms identified by sequencing the genome of summ4-1D mkk1/2 using Illumina sequencing. All primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

For testing whether the summ4-1D mutation is responsible for the suppression of the mkk1/2 mutant phenotype, the SUMM4 gene, including the mutation in the promoter region, was amplified from the genomic DNA of summ4-1D mkk1/2 by PCR using primers MKK6-BamHI-F and MKK6-PstI-R. The DNA fragment was cloned into a modified pCambia1305 vector by the BamHI and PstI sites to express MKK6 under the mutant version of its native promoter. The construct was transformed into plants homozygous for mkk1 and heterozygous for mkk2 by the floral-dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Transgenic plants homozygous for mkk1 mkk2 were identified by PCR in the T1 generation.

Coimmunoprecipitation Analysis

A MEKK1 genomic fragment containing its promoter and coding region was amplified using primers AtMEKK1-genomic-KpnI-F and AtMEKK1-35S-BamHI-R. The fragment was cloned into pCambia1305-3FLAG using the KpnI and BamHI sites. The coding sequence of MKK6 in pCamiba1300-MKK6-CLuc was subcloned into pCamiba1300-35S-3HA using the KpnI and BamHI sites. Agrobacteria strains carrying pCambia1305-MEKK1-3FLAG, pCambia1305-3FLAG (empty vector), or pCambia1300-35S-MKK6-3HA were cultured overnight individually in LB Miller media (10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, and 10 g NaCl per L) containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin, 50 μg/mL gentamycin, and 25 μg/mL rifamycin. The cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 10 mm MgCl2 at optical density at 600 nm (OD600) = 0.6. Agrobacteria carrying 1300-35S-MKK6-3HA were mixed with Agrobacteria carrying empty vector (EV) or pCambia1305-MEKK1-3FLAG at a 1:1 ratio. One hundred fifty millimolar acetosyringone was also added to the Agrobacteria mixtures. The bacteria were incubated for 3 h at room temperature before being infiltrated into Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. The leaf tissue was collected 40 h after infiltration. Two grams of tissue for each sample was collected and ground in liquid nitrogen. Two and one-half volumes of extraction buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 10% Glycerol, 1 mm EDTA, 0.15% Nonidet-P40) plus 10 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), 2% (w/v) polyvinylpolypyrrolidone, 1 mm NaF, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) was added into the ground tissue. After thawing at 4°C for 20 min, the lysates were centrifuged at 13,000g for 30 min, and the supernatants were transferred into new tubes. The anti-FLAG M2 beads (Sigma) were then added into the supernatants and incubated at 4°C for 3 h. After washing with extraction buffer four times, the proteins were eluted by adding 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) buffer (100 mm Tris-Cl pH 6.8, 4% [w/v] SDS, 0.2% [w/v] bromophenol blue, 20% [v/v] glycerol, 200 mm DTT) to the beads and denatured at 99°C for 5 min. The samples were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and analyzed by western blot using anti-FLAG or anti-HA antibodies.

Split Luciferase Assay

Complementary DNA (cDNA) of MKK6 was amplified by PCR using primers MKK6-cLuc-F and MKK6-cLuc-R and cloned into pCamiba1300 CLuc (Chen et al., 2008) using the KpnI and BamHI sites to express MKK6CLuc under a 35S promoter. The cDNA fragment of MEKK1 was excised from pMEKK1-YCE (Gao et al., 2008) using the restriction enzymes BamHI and XhoI and cloned into pCamiba1300 NLuc using the BamHI and SalI sites, and the cDNA fragment of MPK4 was excised from pMPK4-YCE (Gao et al., 2008) using the restriction enzymes KpnI and BamHI and cloned into pCambia1300 3HA-NLuc using the KpnI and BamHI sites (Chen et al., 2008) for expression of MEKK1NLuc and MPK4NLuc under a 35S promoter. N. benthamiana leaves were infiltrated with Agrobacteria (OD600 = 0.2) carrying constructs expressing MKK6CLuc and MEKK1NLuc or MKK6CLuc and MPK4NLuc, along with the negative controls. Plants were kept at 23°C under 16 h light/8 h dark for 2 d before assaying for luciferase activity.

Analysis of MAPK Activation

To analyze flg22-induced MAPK activation, 12-d-old plants grown on 1/2 MS agar plates were sprayed with 100 nm flg22. Samples were collected 0 and 15 min after flg22 treatment. Total protein was extracted from seedlings ground in liquid nitrogen with protein extraction buffer (50 mm HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mm KCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.5% [v/v] Trition-X 100, 1 mm DTT, 1× proteinase inhibitor cocktail). Supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 13,000g for 15 min. The supernatant was added with the same volume of 2× SDS buffer and then boiled at 99°C for 10 min. The proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and phosphorylated MAPKs were detected by immunoblots using antip44/42-ERK antibody (Cell Signaling, #4370S).

To express the MPK4-HA-YCE fusion protein, mesophyll protoplasts were isolated from wild-type (Col-0), summ2-8 mkk1/2, and summ2-8 mekk1-1 plants as previously described (Wu et al., 2009). The protoplasts were transfected with 10 μg of pUC19-MPK4-HA-YCE together with 10 μg of pCambia1300-35S-MKK6-3HA or empty vector. After 16 h of incubation, the transfected cells were treated with 100 nm flg22 for 15 min and then collected by spinning at 120g for 2 min. The cell pellets were added with 30 μL of 2× SDS buffer and boiled for 5 min. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by western blot using antip44/42-ERK or anti-HA antibodies.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative or the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers: At4g08500 (MEKK1), At4g26070 (MKK1), At4g29810 (MKK2), At4g01370 (MPK4), At1g54960 (ANP2), At3g06030 (ANP3), At5g56580 (MKK6), At1g12280 (SUMM2), AAD20950 (EDS1), At3g52430 (PAD4), At3g20600 (NDR1), At2g14610 (PR1), At3g57260 (PR2), and At2g37620 (Actin1).

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. eFP browser view of MKK6 expression during Arabidopsis development

Supplemental Figure S2. Characterization of summ4-2D and transgenic lines overexpressing MKK6 in mkk1 mkk2

Supplemental Figure S3. mkk6-2 mutant seedlings accumulate H2O2 and experience cell death

Supplemental Figure S4. PR1 and PR2 expression levels in wild type and mkk6-3

Supplemental Figure S5. Constitutive defense responses in anp2-2 anp3-3 are dependent on EDS1

Supplemental Figure S6. Growth of Pto DC3000 hrcC− in wild type, anp2-2, anp3-3, and anp2-2 anp3-3

Supplemental Table S1. Genes up-regulated in mkk6-2

Supplemental Table S2. Genes down-regulated in mkk6-2

Supplemental Table S3. Primers used in this study

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kaeli Johnson and Xin Li (University of British Columbia) for discussion and editing of the manuscript, Jean Colcombet (Université Evry Val d’Essonne) for the CA-MPK4 transgenic line, and Yan Li (National Institute of Biological Sciences, Beijing) for genome sequence analysis. They are grateful for the financial support to Y.Z. from Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada and Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI).

Footnotes

This research is supported by funding from Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and Canada Foundation for Innovation.

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Asai T, Tena G, Plotnikova J, Willmann MR, Chiu WL, Gomez-Gomez L, Boller T, Ausubel FM, Sheen J (2002) MAP kinase signalling cascade in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Nature 415: 977–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck M, Komis G, Müller J, Menzel D, Samaj J (2010) Arabidopsis homologs of nucleus- and phragmoplast-localized kinase 2 and 3 and mitogen-activated protein kinase 4 are essential for microtubule organization. Plant Cell 22: 755–771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann DC, Sack FD (2007) Stomatal development. Annu Rev Plant Biol 58: 163–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berriri S, Garcia AV, Frei dit Frey N, Rozhon W, Pateyron S, Leonhardt N, Montillet JL, Leung J, Hirt H, Colcombet J (2012) Constitutively active mitogen-activated protein kinase versions reveal functions of Arabidopsis MPK4 in pathogen defense signaling. Plant Cell 24: 4281–4293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethke G, Pecher P, Eschen-Lippold L, Tsuda K, Katagiri F, Glazebrook J, Scheel D, Lee J (2012) Activation of the Arabidopsis thaliana mitogen-activated protein kinase MPK11 by the flagellin-derived elicitor peptide, flg22. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 25: 471–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi D, Cheng YT, Li X, Zhang Y (2010) Activation of plant immune responses by a gain-of-function mutation in an atypical receptor-like kinase. Plant Physiol 153: 1771–1779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi G, Zhou Z, Wang W, Li L, Rao S, Wu Y, Zhang X, Menke FLH, Chen S, Zhou JM (2018) Receptor-like cytoplasmic kinases directly link diverse pattern recognition receptors to the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 30: 1543–1561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boller T, Felix G (2009) A renaissance of elicitors: perception of microbe-associated molecular patterns and danger signals by pattern-recognition receptors. Annu Rev Plant Biol 60: 379–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Zou Y, Shang Y, Lin H, Wang Y, Cai R, Tang X, Zhou JM (2008) Firefly luciferase complementation imaging assay for protein-protein interactions in plants. Plant Physiol 146: 368–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16: 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui H, Tsuda K, Parker JE (2015) Effector-triggered immunity: from pathogen perception to robust defense. Annu Rev Plant Biol 66: 487–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix G, Duran JD, Volko S, Boller T (1999) Plants have a sensitive perception system for the most conserved domain of bacterial flagellin. Plant J 18: 265–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feys BJ, Moisan LJ, Newman MA, Parker JE (2001) Direct interaction between the Arabidopsis disease resistance signaling proteins, EDS1 and PAD4. EMBO J 20: 5400–5411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei dit Frey N, Garcia AV, Bigeard J, Zaag R, Bueso E, Garmier M, Pateyron S, de Tauzia-Moreau ML, Brunaud V, Balzergue S, et al. (2014) Functional analysis of Arabidopsis immune-related MAPKs uncovers a role for MPK3 as negative regulator of inducible defences. Genome Biol 15: R87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Liu J, Bi D, Zhang Z, Cheng F, Chen S, Zhang Y (2008) MEKK1, MKK1/MKK2 and MPK4 function together in a mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade to regulate innate immunity in plants. Cell Res 18: 1190–1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook J, Rogers EE, Ausubel FM (1996) Isolation of Arabidopsis mutants with enhanced disease susceptibility by direct screening. Genetics 143: 973–982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Gómez L, Boller T (2000) FLS2: an LRR receptor-like kinase involved in the perception of the bacterial elicitor flagellin in Arabidopsis. Mol Cell 5: 1003–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura K, Casais C, Peck SC, Shinozaki K, Shirasu K (2006) MEKK1 is required for MPK4 activation and regulates tissue-specific and temperature-dependent cell death in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem 281: 36969–36976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JD, Dangl JL (2006) The plant immune system. Nature 444: 323–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL (2015) HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods 12: 357–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Q, Qu N, Gao M, Zhang Z, Ding X, Yang F, Li Y, Dong OX, Chen S, Li X, et al. (2012) The MEKK1-MKK1/MKK2-MPK4 kinase cascade negatively regulates immunity mediated by a mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24: 2225–2236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosetsu K, Matsunaga S, Nakagami H, Colcombet J, Sasabe M, Soyano T, Takahashi Y, Hirt H, Machida Y (2010) The MAP kinase MPK4 is required for cytokinesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 22: 3778–3790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krysan PJ, Jester PJ, Gottwald JR, Sussman MR (2002) An Arabidopsis mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase gene family encodes essential positive regulators of cytokinesis. Plant Cell 14: 1109–1120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Dewey CN (2011) RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics 12: 323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Jiang S, Yu X, Cheng C, Chen S, Cheng Y, Yuan JS, Jiang D, He P, Shan L (2015a) Phosphorylation of trihelix transcriptional repressor ASR3 by MAP KINASE4 negatively regulates Arabidopsis immunity. Plant Cell 27: 839–856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Kapos P, Zhang Y (2015b) NLRs in plants. Curr Opin Immunol 32: 114–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhang S (2004) Phosphorylation of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid synthase by MPK6, a stress-responsive mitogen-activated protein kinase, induces ethylene biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16: 3386–3399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAPK Group (2002) Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in plants: a new nomenclature. Trends Plant Sci 7: 301–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Zhang S (2013) MAPK cascades in plant disease resistance signaling. Annu Rev Phytopathol 51: 245–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Chen X, Mang H, Liu C, Yu X, Gao X, Torii KU, He P, Shan L (2015) Differential function of Arabidopsis SERK family receptor-like kinases in stomatal patterning. Curr Biol 25: 2361–2372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan J, Zipfel C (2012) Plant pattern recognition receptor complexes at the plasma membrane. Curr Opin Plant Biol 15: 349–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F (1962) A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant 15: 473–497 [Google Scholar]

- Nakagami H, Soukupová H, Schikora A, Zárský V, Hirt H (2006) A Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase mediates reactive oxygen species homeostasis in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem 281: 38697–38704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishihama R, Ishikawa M, Araki S, Soyano T, Asada T, Machida Y (2001) The NPK1 mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase is a regulator of cell-plate formation in plant cytokinesis. Genes Dev 15: 352–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitta Y, Ding P, Zhang Y (2014) Identification of additional MAP kinases activated upon PAMP treatment. Plant Signal Behav 9: e976155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JE, Holub EB, Frost LN, Falk A, Gunn ND, Daniels MJ (1996) Characterization of eds1, a mutation in Arabidopsis suppressing resistance to Peronospora parasitica specified by several different RPP genes. Plant Cell 8: 2033–2046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen M, Brodersen P, Naested H, Andreasson E, Lindhart U, Johansen B, Nielsen HB, Lacy M, Austin MJ, Parker JE, et al. (2000) Arabidopsis map kinase 4 negatively regulates systemic acquired resistance. Cell 103: 1111–1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu JL, Zhou L, Yun BW, Nielsen HB, Fiil BK, Petersen K, Mackinlay J, Loake GJ, Mundy J, Morris PC (2008) Arabidopsis mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases MKK1 and MKK2 have overlapping functions in defense signaling mediated by MEKK1, MPK4, and MKS1. Plant Physiol 148: 212–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren D, Liu Y, Yang KY, Han L, Mao G, Glazebrook J, Zhang S (2008) A fungal-responsive MAPK cascade regulates phytoalexin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 5638–5643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez MC, Petersen M, Mundy J (2010) Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 61: 621–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux ME, Rasmussen MW, Palma K, Lolle S, Regué AM, Bethke G, Glazebrook J, Zhang W, Sieburth L, Larsen MR, et al. (2015) The mRNA decay factor PAT1 functions in a pathway including MAP kinase 4 and immune receptor SUMM2. EMBO J 34: 593–608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savatin DV, Bisceglia NG, Marti L, Fabbri C, Cervone F, De Lorenzo G (2014) The Arabidopsis NUCLEUS- AND PHRAGMOPLAST-LOCALIZED KINASE1-related protein kinases are required for elicitor-induced oxidative burst and immunity. Plant Physiol 165: 1188–1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su SH, Bush SM, Zaman N, Stecker K, Sussman MR, Krysan P (2013) Deletion of a tandem gene family in Arabidopsis: increased MEKK2 abundance triggers autoimmunity when the MEKK1-MKK1/2-MPK4 signaling cascade is disrupted. Plant Cell 25: 1895–1910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Rodriguez MC, Adams-Phillips L, Liu Y, Wang H, Su SH, Jester PJ, Zhang S, Bent AF, Krysan PJ (2007) MEKK1 is required for flg22-induced MPK4 activation in Arabidopsis plants. Plant Physiol 143: 661–669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T, Zhang Y, Li Y, Zhang Q, Ding Y, Zhang Y (2015) ChIP-seq reveals broad roles of SARD1 and CBP60g in regulating plant immunity. Nat Commun 6: 10159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T, Nitta Y, Zhang Q, Wu D, Tian H, Lee JS, Zhang Y (2018) Antagonistic interactions between two MAP kinase cascades in plant development and immune signaling. EMBO Rep 19: 45324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Soyano T, Kosetsu K, Sasabe M, Machida Y (2010) HINKEL kinesin, ANP MAPKKKs and MKK6/ANQ MAPKK, which phosphorylates and activates MPK4 MAPK, constitute a pathway that is required for cytokinesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 51: 1766–1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarazona S, García-Alcalde F, Dopazo J, Ferrer A, Conesa A (2011) Differential expression in RNA-seq: a matter of depth. Genome Res 21: 2213–2223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas PD, Campbell MJ, Kejariwal A, Mi H, Karlak B, Daverman R, Diemer K, Muruganujan A, Narechania A (2003) PANTHER: a library of protein families and subfamilies indexed by function. Genome Res 13: 2129–2141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thordal-Christensen H, Zhang Z, Wei Y, Collinge DB (1997) Subcellular localization of H2O2 in plants. H2O2 accumulation in papillae and hypersensitive response during the barley—powdery mildew interaction. Plant J 11: 1187–1194 [Google Scholar]

- Toufighi K, Brady SM, Austin R, Ly E, Provart NJ (2005) The Botany Array Resource: e-Northerns, Expression Angling, and promoter analyses. Plant J 43: 153–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F-H, Shen S-C, Lee L-Y, Lee S-H, Chan M-T, Lin C-S (2009) Tape-Arabidopsis sandwich—a simpler Arabidopsis protoplast isolation method. Plant Methods 5: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Meng J, Meng X, Zhao Y, Liu J, Sun T, Liu Y, Wang Q, Zhang S (2016) Pathogen-responsive MPK3 and MPK6 reprogram the biosynthesis of indole glucosinolates and their derivatives in Arabidopsis immunity. Plant Cell 28: 1144–1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Q, Chen JG, Ellis BE (2011) AtMPK4 is required for male-specific meiotic cytokinesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J 67: 895–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Wu Y, Gao M, Zhang J, Kong Q, Liu Y, Ba H, Zhou J, Zhang Y (2012) Disruption of PAMP-induced MAP kinase cascade by a Pseudomonas syringae effector activates plant immunity mediated by the NB-LRR protein SUMM2. Cell Host Microbe 11: 253–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Liu Y, Huang H, Gao M, Wu D, Kong Q, Zhang Y (2017) The NLR protein SUMM2 senses the disruption of an immune signaling MAP kinase cascade via CRCK3. EMBO Rep 18: 292–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]