Abstract

Cryopreservation has utility in clinical and scientific research but implementation is highly complex and includes labor-intensive cell-specific protocols for the addition/removal of cryoprotective agents and freeze-thaw cycles. Microfluidic platforms can revolutionize cryopreservation by providing new tools to manipulate and screen cells at micro/nano scales, which are presently difficult or impossible with conventional bulk approaches. This review describes applications of microfluidic chips in cell manipulation, cryoprotective agent exposure, programmed freezing/thawing, vitrification, and in situ assessment in cryopreservation, and discusses achievements and challenges, providing perspectives for future development.

Keywords: microfluidics, cryopreservation, freezing/thawing, cryoprotective agent loading/unloading, vitrification

1. Introduction

Cryopreservation is the use of very low temperatures to preserve structurally intact living cells and tissues. Cryopreservation is a science/technology for long-term storage of cells, tissues, and organs at cryogenic temperatures (usually in liquid nitrogen or liquid nitrogen vapors) and allows resumption of normal functions after retrieval from a cryobank (Kuleshova and Hutmacher, 2008). To date, cryopreservation has permitted breakthroughs in biomedical applications including assisted reproductive medicine, stem cell technologies, cell therapies, tissue engineering, development and in vitro screening of anticancer drugs, pharmacology, and basic scientific research (Benelli et al., 2013; Feng et al., 2011; Julca et al., 2012; Palasz and Mapletoft, 1996; Popova et al., 2016; Smorag and Gajda, 1994; Teixeira da Silva, 2003; Wang, B. et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2012). Trillions of cells are biopreserved globally for daily clinical use. For example, cryopreservation of human oocytes preserves future fertility of young females who may experience future infertility due to exposure to environmental/occupational hazards or aggressive medical treatments and such cryopreservation avoids moral, ethical, and religious issues associated with human embryo preservation (Choi et al., 2015a; Nagashima et al., 1995; Palasz and Mapletoft, 1996; Rall and Fahy, 1985; Redmond et al., 1988; Smorag and Gajda, 1994; Steponkus et al., 1990; Trounson and Mohr, 1983). Similarly, due to the significant decline in sperm quality in global males (Merzenich et al., 2010), increased incidence of azoospermia and oligospermia, and rapid increases in testicular cancer in young males, spermatozoa and spermatogonia stem cell preservation can be undertaken (Zou et al., 2013) and cryopreservation of sperm, ova, and fertilized eggs is currently in clinical practice worldwide.

In addition, stem cell cryopreservation is indispensable to ensure manufacturing, distribution, and unpredictable demands can be addressed and efficient cryopreservation can enable marketing of stem cell products (Xu, 2011). Cryopreservation of immune cells with high efficiency and quality is an important prerequisite for meeting bio-immunotherapy demands, which is an emerging cancer treatment with reportedly fewer side effects and more promising outcomes. In general, efficient and reliable storage of large quantities of diagnostic and therapeutically relevant cells, including blood cells, gametes, embryos, stem and immune cells, is crucial to guarantee their permanent availability (Ihmig et al., 2013).

Current cryopreservation techniques fall into three categories (He, 2011): programmable slow freezing, vitrification, and low-CPA vitrification (ultra-rapid freezing). The most common, programmable slow freezing allows freezing of low-CPA cell solutions and ice crystallizes in both extra- and intracellular solutions. Most mammalian cells are frozen at 1 °C/min with 1.5 M CPA (Zhang et al., 2011a), and the comprehensive minimization of both the solution and the intracellular ice injuries corresponds to the optimal cooling rate, providing more cell survival (Leibo et al., 1970; Mazur, 1984). Cryo-injuries introduced by solution effects (elevated concentration caused by ice formation and growth), extra- and intracellular ice formation (EIF and IIF) and osmotic pressure-driven cell dehydration, are inevitable even after adequate optimization of freeze-thaw cycles. Vitrification is an alternative well-established technique offering the benefits of cryopreservation without ice crystal formation damage (Fahy, 1981; Rall and Fahy, 1985). Vitrification uses high concentrations of CPAs to prevent ice formation, and low-CPA vitrification uses ultra-rapid freezing to suppress ice formation. Of note, high-CPA and rapid cooling can promote vitrification but compared with programmable slow freezing, vitrification and low-CPA vitrification usually require greater CPA (4–8 M) and more rapid cooling (up to ~ 105 °C/min). Both the loading/unloading processes of such high concentrations of CPAs, and the ultra-rapid cooling rates required for vitrification, complicate this method within the scope of traditional freeze-thaw techniques for mass volume cell suspensions within routinely used containers. Conventional cryopreservation methods are commonly used for manipulating larger samples, where cell-specific CPA loading/unloading, cell scale optimal freezing/thawing, and ultra-rapid and uniform freeze/thawing are hard to achieve. However, microfluidic applications may address these problems.

Recently, rapid development of micro- and nanotechnologies has allowed implementing entire cryopreservation procedures on-chip. Due to numerous intrinsic features, such as ease of mass production and specific designs and changes, ease of component integration, disposability, low cost, and requirement of smaller reagents or analyte volumes, as well as ease of rapid implementation of a high-efficiency mixture, microfluidics techniques emerged in early 1980 have been introduced for cryopreservation approaches. These fields include controlled loading/unloading of CPAs into the cells with stepwise, linear and complex CPA profiles (Heo et al., 2011; Park et al., 2011; Song et al., 2009), programmable freeze-thawing cycles (Afrimzon et al., 2010; Deutsch et al., 2010; Li et al., 2010), and low-CPA vitrification by ultra-rapid freezing (Choi et al., 2015a; He et al., 2008; Zou et al., 2013) using microfluidics. Such innovation offers a tremendous potential to revolutionize cryopreservation.

This review highlights applications of contemporary microfluidic techniques in cryopreservation, revealing new insights into highly cell-type specific cryopreservation approaches, and describing new tools to manipulate cells and their interactions with the extracellular microenvironment.

2. Fundamentals of Cryopreservation

Cryopreservation is the successful long-term maintenance of cellular or tissue biological function at low temperatures, suppressing metabolism and biochemical reactions, effectively ceasing “biological time” (Mullen and Critser, 2007). Although ultra-low temperatures offer long-term preservation, cryo-injuries such as ice formation-induced mechanical stress and freeze concentration-induced physiochemical deviation from physiological states are inevitable (Gao and Crister, 2000; Mazur, 2004; Mazur et al., 1972). To prevent cell death by freezing/thawing, CPAs have been introduced and are widely used; although some are toxic (Meryman, 1971a).

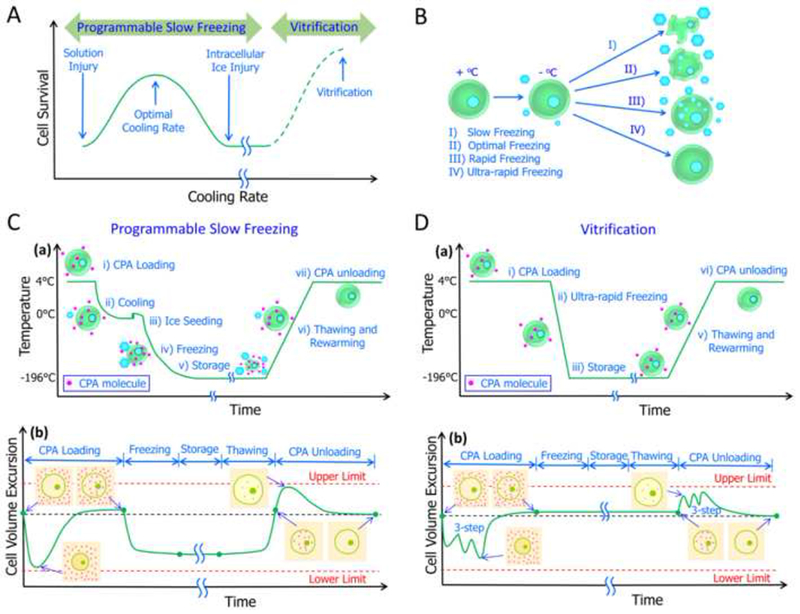

The underlying theory of cryopreservation appears in Figure 1. The inverted ‘U’ shaped relationship between cell survival and cooling (Figure 1A) has been summarized in the literatures prior to understanding the mechanism behind it (Acker, 2007; Mazur, 1984, 2004; Mazur et al., 1972; Mullen and Critser, 2007). During slow freezing cryopreservation, cells may suffer injuries caused by deviations of the extra- and intracellular solutions from the physiological environment and extra- and intracellular ice formation (Figure 1B), as summarized by the “two-factor hypothesis” offered by Mazur (Mazur, 1970, 1984). Briefly, prolonged exposure to extracellular freezing (“solution injury”) and intracellular freezing (“IIF injury”) are two competitive cell water fates and both are determining factors for cell survival (Mazur, 1970, 1984, 2004). Both solution injury caused by over-slow cooling and IIF injury caused by over-rapid cooling are fatal to cells and the combination of tolerable solution and IIF injury offers the best cell survival and corresponds to optimal cooling (He, 2011; Mazur, 1970, 1984, 2004; Shimada, 1978; Toner et al., 1990; Zhao et al., 2006; Zhao, G. et al., 2014) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Basic theory for cryopreservation.

(A) Cell survival corresponds to cooling rate. (B) Cooling-rate dependent cell fates during freezing. Typical thermal profiles and cell volume responses for slow programmable freezing (C) and vitrification (D). (a) Temperature profiles; (b) Cell volume excursions. (A) adapted from (Mazur, 1984) and (He, 2011) with permission; (B) Reproduced from (Zhao, G. et al., 2014) with permission; (C) and (D) adapted from (Acker, 2008) and (Zhao et al., 2016) with permission.

Temperatures and corresponding cell volume excursions during cryopreservation (Acker, 2008; Mazur, 1984, 2004) appear in Figure 1C (a, b) and 1 D (a, b). Typical cryopreservation procedures involved in programmable slow freezing can be summarized this way (Gao and Crister, 2000; Mazur, 1984, 2004; Zhao et al., 2016): addition of CPAs to cells before cooling; cooling cells below the solution freezing point; triggering ice formation by seeding to eliminate overcooling; sample freezing towards a low temperature (−196 °C) at a controlled rate; storage; thawing and re-warming; and CPA removal. Cell volume excursion during cryopreservation appears in Figure 1C (b) and it can be used as an intuitive indicator of osmotic injury (Benson et al., 2005a; Benson et al., 2012; Davidson et al., 2014; Lusianti et al., 2013): the cell may be damaged once the volume change is beyond upper/lower limits. Of note, storage at very low temperature (< −180 °C) is not as important as freeze-thaw cycles across the intermediate temperature zone (−15 °C to −60 °C) which are damaging (Gao and Crister, 2000; Mazur, 1984). Thus, optimization of CPA loading/unloading and freezing/thawing is needed for successful slow-freezing cryopreservation.

For vitrification or low-CPA vitrification, cooling process is very simple compared to programmable slow freezing because the sample is directly immersed in liquid nitrogen for the fastest cooling available (Fahy, 1986b; Fahy et al., 1984; Huang et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016) (Figure 1D (a)). Because no ice forms in either extra- or intracellular solution, no water or CPA transport across the cell membrane during freezing/thawing occurs (Fahy and Wowk, 2015) (Figure 1D (b). However, because vitrification or even low-CPA vitrification requires high (which are toxic) concentrations of CPA (4–8 M) compared with programmable slow freezing, severe osmotic injury during addition and removal of CPA may occur (Fahy and Wowk, 2015). Thus, protocols for adding/removing CPAs during vitreous cryopreservation must be carefully designed, and multi-step addition and removal is often needed to minimize osmotic injuries (Benson et al., 2012; Davidson et al., 2014; Lusianti et al., 2013). Of note, for simplicity, three-step addition and removal of CPAs as a representative case, appears in Figure 1D (b). Ultra-rapid cooling is key to low-CPA vitrification, but it is technically very difficult for large volume samples to cool rapidly (Fahy and Wowk, 2015; Fahy et al., 2009; Wowk, 2010). Furthermore, Mazur’s group recently proved that a very high warming rate is considerably more important to the attainment of high survivals than is a very high cooling rate (Jin and Mazur, 2015; Kleinhans et al., 2010; Seki et al., 2014; Seki and Mazur, 2008, 2009). Ideal rewarming should be rapid enough to avoid devitrification and recrystallization, which may fatally injure cells (Fahy and Wowk, 2015), however, it’s also hard to achieve a so rapid warming rate for large volume samples. Cell survival and cooling for vitrification, including low-CPA vitrification (He, 2011), is depicted as the dash line in Figure 1A.

2.1. CPA loading and unloading

Although cryopreservation offers a powerful tool for long-term storage and off-shelf availability of biological materials, CPAs are required. CPA received great attention since its discovery in 1948 (Meryman, 1974; Polge et al., 1949; Smith and Polge, 1950); they prevent stress of freeze/thawing while causing cytotoxicity and osmotic shock (Fahy, 1994; Luyet and Rapatz, 1971; Meryman, 1971b). CPA loading prior to freezing/unloading after thawing expose cells to a series of anisotonic solutions, and as a result, cells undergo volume excursions (Acker, 2008; Gao and Crister, 2000; McGrath, 1997) (Figures 1C (b), 1D (b)). During loading of a permeable CPA, the chemical potential of intracellular water exceeds that of extracellular water, and cells first dehydrate with the outflow of cell water, and then re-swell in the face of water backflow of water plus the CPA (Gao and Crister, 2000). In contrast, during CPA unloading, the opposite occurs (Gao and Crister, 2000). Transport of water across a cell membrane is always more rapid than the rate of the diffusion of larger CPA molecules (Gao and Crister, 2000). Complete cell volume excursion and how this occurs appears in Figures 1C (b) and 1D (b). As shown, minimal and maximal values for cell volume occur during CPA addition and removal, respectively and these volumes during osmotic responses may cause osmotic injuries that reduce cell recovery and survival (Song et al., 2009). Accordingly, optimization of CPA loading/unloading requires confining cell volumes in a minimal/maximal range (Benson et al., 2011; Benson et al., 2012; Davidson et al., 2014; Lusianti et al., 2013).

Except for osmotic injuries, CPA toxicity is also a dominant factor for successful cryopreservation of living systems by both freezing and vitrification (Benson et al., 2012; Cordeiro et al., 2015; Davidson et al., 2015; Fahy, 1981, 1986a, 2010; Fahy and Karow, 1977; Fahy et al., 1990; Fahy et al., 1984; Fahy et al., 2004a, b; Fahy et al., 2004c). Significant effort has been devoted to the study on CPA toxicity neutralization, especially in the direction of organ vitrification (Fahy, 1981, 1986b, 1987, 1994; Fahy et al., 1985; Fahy et al., 2004c; Khirabadi et al., 1988). Benson et al. pioneered a toxicity cost function (it reflects the cumulative damage caused by toxicity) based mathematical optimization of the procedures for CPA equilibration (addition and removal), the predictions on human oocytes yield significantly less toxicity than conventional stepwise procedures (Benson et al., 2012; Davidson et al., 2014). Its extension form was further successfully used for the design of CPA equilibration for adherent endothelial cells (Davidson et al., 2015). Compared with programmed slow freezing, vitrification/low-CPA vitrification requires comparatively more CPA; therefore CPA addition and removal processes are more time consuming and costly (Choi et al., 2015a; Choi et al., 2015b; Huang et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016).

A routine method for CPA loading/unloading involves repeated centrifugation, supernatant removal, addition of new solutions, and cell resuspension (Lusianti et al., 2013; Lusianti and Higgins, 2014; Zhurova et al., 2014a; Zhurova et al., 2014b). Although the manpower and material resources involved are expensive, and the samples are exposed to contamination risk, this process is difficult to automate within the framework of the traditional processing (Lusianti et al., 2013). More recently, however, microfluidic platforms have been adopted to avoid potential osmotic and toxic injuries to cells using programmed, controlled, complex CPA loading and unloading profiles (Heo et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2015; Lusianti and Higgins, 2014). This approach has been more efficient, robust, and safe, while still enabling high throughput.

2.2. Cooling and warming

Contrary to intuition and common sense, cell fates are determined by the lethality of the temperature “danger zone” (~ −15 °C to −60 °C) that a cell must traverse twice—once during cooling and once during warming, instead of the storage at very low temperatures (Mazur, 1984, 2004). The typical physical events that occur during slow-freezing cryopreservation process (Acker, 2007) are depicted in Figure 1C, and more detailed cooling rate-dependent cell freezing responses (Mazur, 1984; Toner et al., 1990), including low-CPA vitrification by ultra-rapid freezing, are shown in Figure 1B. After exposure to subzero temperatures below the CPA solution freezing point, cells and their surrounding medium may experience different physical events that are cooling rate dependent (Acker, 2007; Mazur, 1984). In Figure 1B, Case I depicts slow freezing that allows sufficient cell dehydration to minimize supercooling of intracellular solutions, resulting in severe cell shrinkage-induced osmotic injuries and high concentration-induced solution injuries (Zhao, G. et al., 2014). In contrast, preventing the freezing of intracellular water, as seen in Case II, allows optimal freezing and partial cell dehydration plus innocuous IIF, resulting in comparatively high cell survival corresponding to tolerable compound injuries (Zhao, G. et al., 2014). For Case III, rapid freezing causes insufficient cell dehydration and increased super cooling of the intracellular solution, which may attain re-equilibrium by intracellular freezing, resulting in serious IIF injuries (Zhao, G. et al., 2014). For Case IV, ultra-rapid freezing induces both extra- and intracellular solutions to form a glass instead of crystallizing, resulting in most cell survival corresponding to complete prevention of cryo-injuries by vitrification (namely, low-CPA vitrification) (Zhao, G. et al., 2014). The schematic of cooling rate-dependent cell survival (He, 2011) is depicted in Figure 1A. As shown for conventional programmable slow freezing, significant IIF and freeze concentration-induced excessive dehydration are the two dominant cryo-injuries that determine cell survival (Gao and Crister, 2000; Mazur, 1984). The freeze concentration-induced cell damage effect is apparent for slow-cooling rates, which is decreased with an increased cooling rate (Mazur, 1984). However, IIF becomes dominant only when the cooling rate is sufficiently high (Mazur, 1984, 2004). How these different dependencies of each damage factor is related to cooling rate is depicted by a classical inverted U curve (Figure 1A, solid line) (He, 2011; Mazur, 1984). For conventional high-CPA vitrification, the cooling rate is not as important; the CPA concentration is high enough to suppress ice formation (Fahy and Wowk, 2015). Instead, osmotic stress and toxicity introduced by high CPA concentrations are more damaging (Fahy and Wowk, 2015). For low-CPA vitrification by ultra-rapid cooling, the classical inverted U curve can be extended to the ultra-rapid cooling rate domain, in which cell survival increases with increased cooling rate (dashed line in Figure 1A) (He, 2011); which is achievable when the cooling rate is as high as 103–106 °C/min (Fahy and Wowk, 2015; Karlsson et al., 1994; Zhao et al., 2006; Zhao, G. et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2013).

With respect to conventional cryopreservation platforms, difficulty arises in ensuring that all cells in a large volume are cooled at the specified optimal cooling rate for the slow freezing program (Allen et al., 1975; Kilbride et al., 2016; Slabbert et al., 2015). Furthermore, preventing cytotoxicity from high CPA concentrations required to decrease critical cooling rates necessary for vitreous cryopreservation is of importance (Fahy and Wowk, 2015). Unprecedented successes in cell cooling and warming have been accomplished with emerging novel microfluidic platforms which have intrinsic advantages, especially for cell-specific manipulation and strong controllability for rapid thermal responses (Huang et al., 2015; Lai et al., 2015a; Pyne et al., 2014; Vom et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2015).

3. Characterization of Cell Membrane Transport Properties

To minimize negative effects caused by CPA addition prior to freezing and removal after thawing, carefully designed protocols based on fundamental biophysical principles are needed (Liu et al., 2015; McGrath, 1997). Cell membrane transport properties must be determined using osmotic shift experiments to optimize the addition and removal of CPAs. Cell membrane transport properties (or permeability)-related parameters include (Mcgrath and Krings, 1986; Woods et al., 1999) hydraulic conductivity (Lp), CPA permeability (Ps), and activation energies of both parameters (ELp, EPs).

Microfluidics provide an ideal platform for microscale cell manipulation and permit precise description of cell osmotic behaviors with controlled CPA loading/unloading. Various microfluidic devices have been applied for characterization of cell membrane transport properties by studying the cell osmotic response.

Microfluidic approaches have also been adopted for quantification of cell membrane permeability for more than 10 years and these are classified in two categories according to the materials from which they are made: polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and non-PDMS materials. To study osmotic responses, Chen et al. (Chen et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2008) reported the manufacture of a PDMS microperfusion chamber and Takamatsu and coworkers (Takamatsu et al., 2004) developed a non-PDMS sandwich structured microperfusion chamber, which was improved by Liu and coworkers (Liu et al., 2015). Both chamber types have been implemented for accurate depiction of cell volume responses after osmotic shifts. Although there also have been interesting studies on microfluidics for characterization of cell membrane transport properties for adherent cells (Fry and Higgins, 2012; Verkman, 2000), this review focuses on microfluidic devices and methods for suspended cells. Hereafter, we summarize microfluidic-based perfusion chambers for measuring cell membrane biophysical properties and minimization of osmotic injury by accurately controlled biotransport across the cell membrane.

3.1. Sandwich-structured microfluidic perfusion chamber

Takamatsu’s group used a 50-μm-thick silicone rubber sheet (40 mm × 4 mm) sandwiched between two silicon glass slides to form a single straight microfluidic channel (Takamatsu et al., 2004). Before perfusion, the upper silicone glass was removed and the cell suspension was pipetted into the channel prior to replacing the top silicone glass. After ~10 min, cells had settled on the upper surface of the bottom glass. When the perfusion solution was controlled at low velocity, most cells did not move against the fluid. Unlike conventional microdiffusion designs, (McGrath, 1985) or the microfluidic perfusion chamber method (Gao et al., 1996), the extracellular solution directly shifted from low to high concentration (or inversely) without the aid of a dialysis/porous membrane. To improve data processing precision, the concentration change of the extracellular solution was simultaneously measured using a laser interferometer during the perfusion experiments.

Compared with traditional micro-devices or the more recent PDMS microfluidic perfusion chambers, the sandwich-structured microfluidic perfusion chamber is low cost, easy to make, and can be accurately configured for extracellular solution concentrations. However, inconvenient features of this design include a limited observation area (especially after the aluminum temperature-controlled stage is mounted, the view field is confined by the 10-mm-diameter hole at the center of the aluminum block, making it hard to move the chamber independent of the stage). Also, there is an inconvenient sample loading process (the upper silicon glass has to be uncovered to load the cell suspension for each run). Inaccurate temperature control of the extracellular solution (due to an external thermocouple of the microchannel) and the laser interferometer is comparatively expensive and a professional setup is required.

3.2. PDMS microfluidic perfusion chamber

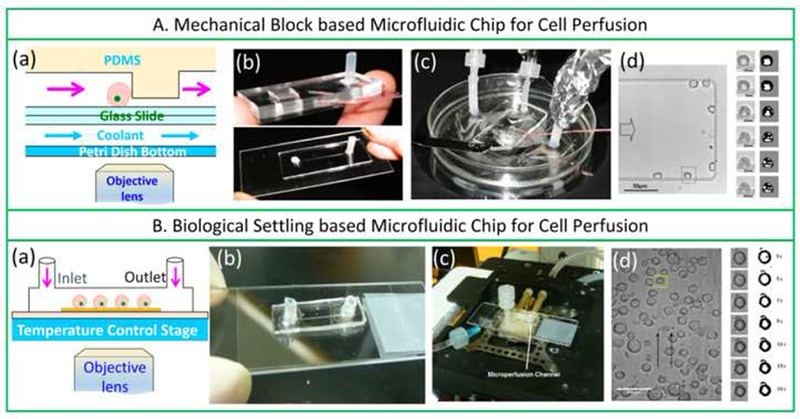

More recently, Chen and colleagues (Chen et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2008) fabricated a PDMS-based microfluidic perfusion system using soft lithography technology (Figure 2A). The PDMS layer containing a microchannel was inverted and sealed on a glass slide to form the microfluidic chamber, and the entire construct was placed into the temperature-control chamber. Advantages of this microfluidic perfusion chamber include cost effectiveness, disposability, reduced labor customized microchannels allow cell confinement in a monolayer state to prevent cell overlapping. Disadvantages of the microfluidic perfusion chamber are that the mask has to be re-designed and re-manufactured to make a microchannel with a different size and geometry, which is time consuming. Moreover, cells can be trapped and enriched by the block during perfusion and the shear force from the upper stream and the counter force from the block tend to distort the cells, inevitably introducing cell volume measurement errors that are thought to be due to changes in concentration of the extracellular solution in theoretical models. The T-type thermocouple temperature sensor is embedded in the PDMS near the microchannel instead of being in the extracellular solution, which may introduce errors in temperature monitoring because PDMS is a poor heat conductor.

Figure 2. PDMS microfluidics for quantitative examination of cell osmotic responses.

Mechanical block- (A) and biological settling- (B) based microfluidic chips for cell perfusion. (a–d) are schematics of the microfluidic perfusion chamber, the microperfusion system, and the typical micrography of cells perfused in the microchannel of the two microfluidic chips, respectively. (A) Reproduced from (Chen et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2008) with permission and courtesy of Prof. Chen; (B) Reproduced from (Tseng et al., 2011) with permission and courtesy of Dr. Shu.

Later, Tseng and coworkers (Tseng et al., 2011) described another design for the PDMS microfluidic perfusion chamber (Figure 2B), whereby the block of the PDMS layer (Figure 2A) was removed, and a PDMS layer with a rectangular microchannel (200 μm × 200 μm × 2 cm) was bonded onto a glass slide (Figure 2B). The upper surface of the glass was treated with 50 μg/mL poly-D-lysine hydrobromide to immobilize cells. During perfusion, cell volume responses were observed and recorded in situ. To minimize inconsistency between experiments and the theoretical assumption (step-wise change) for extracellular solution concentration profiles, the perfusion flow velocity was increased to 36 μL/min to minimize the solution replacement time to <0.4 s (Tseng et al., 2011). Of note, commercially available cryostage (HSC 601; INSTEC Inc., Boulder, CO) was used for temperature regulation in the perfusion system for ease of measurement of cell membrane transport properties at very low temperatures (−5, −10, and −20 °C). Temperature dependence in both Lp and Ps of megakaryocytes was discontinuous between 37 °C and −20 °C (Tseng et al., 2011). Compared with the PDMS microfluidic perfusion chamber developed by Chen (Chen et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2008), cell volume responses were more accurately measured in the device developed by Tseng et al. (Tseng et al., 2011) since the aforementioned cell distortion caused by the upper stream and the counter force from the block was avoided, but most advantages and disadvantages were the same.

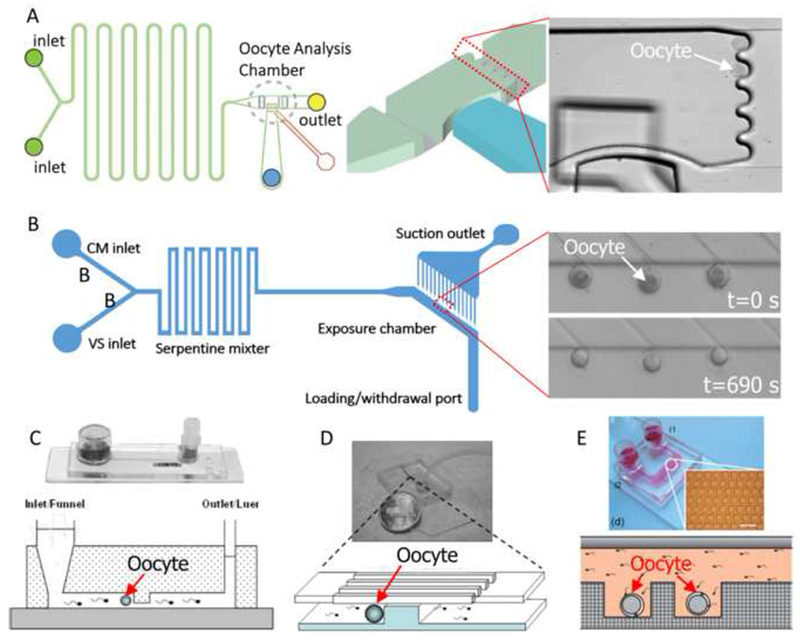

Heo et al. (Heo et al., 2011) developed a two-layer, PDMS oocyte-specific microfluidic device for quantification of cell volume responses during CPA loading (Figure 3A). In their design, a series of semicircular holders were introduced to hold single oocytes for perfusion. Cell volume excursions during various CPA loading protocols, including step-wise, linear, and complex, were comparatively investigated. Using this microdevice, CPA loading processes of oocytes were optimized by minimizing exposure time and cell volume excursion. Lai and colleagues (Lai et al., 2015a) developed a novel microfluidic CPA exchange device (Figure 3B) and reported that minimizing cell shrinkage at a given minimum cell volume and CPA exposure time improves outcomes. Furthermore, this approach allows a new CPA exchange protocol using automated microfluidics to improve oocyte and zygote vitrification. Except for the above mentioned microfluidic devices that are directly used for investigation of the cell membrane transport properties of oocytes, there are also several reports on microfluidic platforms for assisted reproduction, where the microfluidic perfusion chambers or channels may be adopted for CPA perfusion. Clark et al. and Wheeler et al. (Clark et al., 2005; Wheeler et al., 2007) designed a microchannel device (Figure 3C) that mimics the function of the oviduct and creates a flow pattern of spermatozoa past the oocytes similar to the pattern in the oviduct, and successfully performed fertilization of pig oocytes. Suh et al. (Suh et al., 2006) proved that in vitro fertilization of murine oocytes can be conducted within microfluidic channels, where a modified microfluidic device (Figure 3D) was used. Later, Han et al. reported a novel microwell-structured microfluidic device (Figure 3E) that integrates single oocyte trapping, fertilization and subsequent embryo culture, this device can create a well-controlled microenvironment for individual zygotes. All these microfluidic devices are well-designed with controlled sizes of the microstructures, and may be potentially adopted for investigation of osmotic behaviors of oocytes, zygotes or embryos.

Figure 3. Schematics of the representative oocyte-specific microfluidic perfusion devices.

(A) A two-layer PDMS device on glass, including a microfluidic network layer (lower layer) and a control layer (upper layer) to handle single oocyte for perfusion. Reproduced from (Heo et al., 2011; Lai et al., 2015) with permission. (B) A two-layer PDMS device, including a microfluidic channel layer that houses the oocytes and delivers CPA solutions, and a holding pipette layer for suction of the oocytes. Reproduced from (Lai et al., 2015a) with permission. (C) A first microfluidic device used for in vitro fertilization of pig oocytes. (D) A modified microfluidic device used for in vitro fertilization of mouse oocytes. (C) and (D): Reproduced from (Swain et al., 2013) with permission. (E) A novel microwell-structured microfluidic device that integrates single oocyte trapping, fertilization and subsequent embryo culture. Reproduced from (Han et al., 2010) with permission.

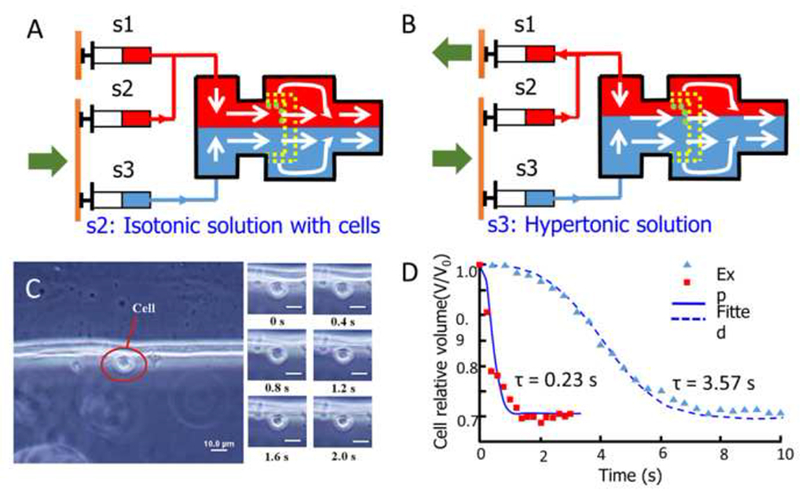

More recently, Lyu et al. (Lyu et al., 2014) developed a PDMS microfluidic chip with hydrodynamic switching to measure cell membrane hydraulic conductivity (Figure 4). A specially designed block structure in the PDMS layer was used for cell trapping, similar to the block adopted in the design by Chen’ laboratory (Chen et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2008) (Figure 2A). Cells were first trapped by the block using controlling syringes (s2) and (s3) at a constant flow while keeping the syringe (s1) inactive (Figure 4A). The syringe pump (s1) was then triggered to aspirate the isotonic solution containing the cells to induce hydrodynamic switching and thereby move the hypertonic solution over the trapped cells (Lyu et al., 2014) (Figure 4B). By changing the aspiration rate of the syringe pump, the change rate of the extracellular solution can be controlled for cells trapped at locations in which the solution switching dynamics are characterized (Figure 4B), and cell responses were simultaneously recorded (Figure 4C) (Lyu et al., 2014). Hydraulic conductivities of articular cartilage chondrocytes were also measured with two different switching time constants (Figure 4D), and they found that Lp was independent of extracellular solution change rates. Although Lp values were stated to be independent of the shear force caused by the perfusion flow, obvious cell reshaping was observed (Figure 4C), which may introduce error into subsequent data processing because non-spherical cells are not used by cryobiologists for calculating permeabilites (Takamatsu et al., 2004; Zawlodzka and Takamatsu, 2005). It should be pointed out that the main idea for controllable mixing of extracellular solutions was firstly accomplished by Takamatsu’s group in 2004 (Takamatsu et al., 2004) using a much simpler device, whereby quantitative analysis of the extracellular solutions concentration profiles during osmotic shift experiments was performed. The PDMS microperfusion chamber has similar advantages and disadvantages to those mentioned previously (Chen et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2008).

Figure 4. Measurement of cell membrane transport properties using hydrodynamic switching.

(A) Cell trapping by two laminar flows with the same velocity. (B) Changing the extracellular solution by adjustment of the velocity ratio of the two flows. (C) Cell volume responses to the change in extracellular osmolality (switching time constant τ = 0.23 s). (D) Relative cell volume corresponds to time during hydrodynamic switching with two different time constants. Reproduced from (Lyu et al., 2014) with permission.

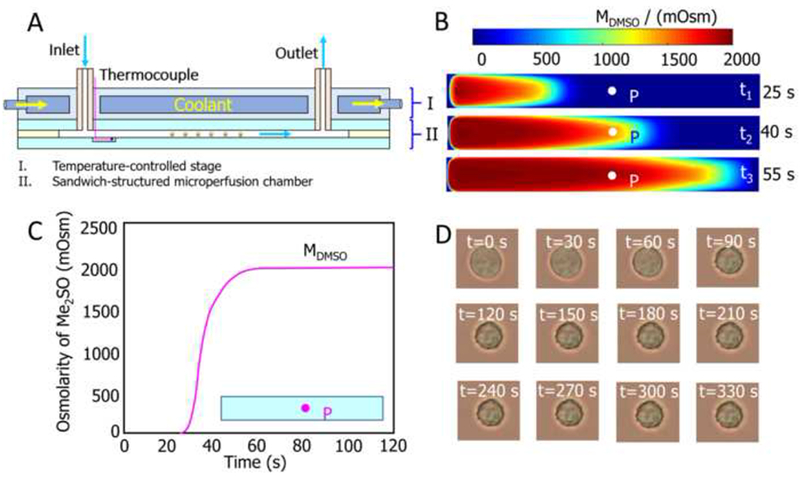

3.3. Improved sandwich structured microfluidic perfusion chamber

Based on the sandwich-structured microfluidic perfusion chamber originally developed by Takamatsu’s group (Takamatsu et al., 2004), Zhao’s group (Liu et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2013; Wang, J.Y. et al., 2014; Yue et al., 2014; Zhao, 2012) proposed an improved design (Figure 5) by avoiding most of the disadvantages. First, a transparent plexiglass temperature control unit was introduced to provide an expanded vision compared with metal units (Figure 5A). Then, a tiny thermocouple was embedded into the microchannel during manufacturing to ensure accurate monitoring of the temperature in the local extracellular solution. Next, a dedicated capillary for cell loading was introduced and the profile for extracellular solution concentration changes during CPA loading/unloading was pre-determined with experimentally validated finite element analysis (Figures 5B and C). A Teflon (PTFE) tube with a thicker wall (1.2 mm) was used to connect the system to minimize the pressure fluctuation upon various flow controls, and instead of hard assembling with bolts or glue, the components shown in Figure 5A were tightly clamped with a file clip, providing tight adherence but sufficient protection by stress relaxation.

Figure 5. Improved sandwich-structured microperfusion chamber for quantitative characterization of cell membrane permeability.

(A) Sectional view of microchamber. (B) Transient concentration distributions in the microchannel. (C) Concentration profile of point ‘P’ during osmotic shift. (D) Micrographs for typical cell volume responses. Reproduced from (Liu et al., 2015; Niu et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016) with permission.

The features of this improved perfusion system make it robust, low cost, easy and fast to assemble, highly precise and reusable and durable. Due to the fact that the sealing process of PDMS on glass with oxygen plasma is irreversible (Chen et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2008), the PDMS microfluidic perfusion chamber cannot be disassembled for washing and reuse, while the sandwich structured one intrinsically owns this feature. Till now, this system has been successfully used for optimization of CPA loading/unloading of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (Niu et al., 2016), investigation of dual dependence of the transport properties of Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf21) insect cells on temperature and CPA concentration (Wang et al., 2013), measurement of transport properties of porcine adipose-derived stem cells (Wang, J.Y. et al., 2014), and to explore the effect of nanoparticles on osmotic responses of pig iliac endothelial cells and Sf21 cells (Yue et al., 2014).

3.4. MEMS based microfluidic coulter counter

The aforementioned microfluidic microperfusion chambers are all originally designed to work under a microscope (Gao et al., 1996; Liu et al., 2015). Cell volume changes are usually acquired through a CCD or digital camera mounted on the microscope, with the assumption that the projected area of the cell can be converted to its volume (McGrath, 1985; Takamatsu et al., 2004; Yoshimori and Takamatsu, 2009; Zhao et al., 2012). However, for non-spherical or irregularly shaped cells, i.e., human erythrocytes, platelets and sperms, these devices are no longer applicable.

Coulter counter, one of the electronic particle counters, as an electrical impedance based sensor for measurement of the size and concentration of biological cells or particles suspended in an electrolyte being independent their shapes, has been well-developed and widely used in the medical and industrial fields (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2004; Zhe et al., 2007) since its invention by Wallace H. Coulter in 1949 (Wallace H., 1953). The Coulter principle demonstrates that a change in impedance being proportional to the volume of a particle traversing an orifice will be induced by pulling the particle through the orifice concurrent with an electrolyte (Wallace H., 1953; Walter R. and Wallace H., 1971). Coulter counter has been an alternative while indispensable method for characterization of cell membrane transport properties in the field of cryopreservation (Agca et al., 2005; Benson et al., 2005b; Ebertz and McGann, 2002, 2004; Elmoazzen et al., 2002; Glazar et al., 2009; Liu et al., 1995; Liu et al., 1997; Si et al., 2006; Toupin et al., 1989a, b; Woods et al., 1999), while the commercially available Coulter counters are usually costly, relative large in size, require large sample volumes, and unfit for rapid processing of samples (Wu, Y.F. et al., 2010), besides, they do not support successive volume measurements for single cells (Sun et al., 2010). Consequently, diverse microelectromechanical system (MEMS) based microfluidic Coulter counters were successfully fabricated to overcome all the disadvantages mentioned above while intrinsically own the features as cost effective, low volume requirement for both cells and reagents, compact and portable, and possible integration with other systems (Gawad et al., 2001; Jasim et al., 2015; Koch et al., 1999; McPherson and Walker, 2010; Murali et al., 2009; Nieuwenhuis et al., 2004; Rodriguez-Trujillo et al., 2008; Scott et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2010; Wood et al., 2007; Zhang, M. et al., 2012; Zhe et al., 2007; Zheng et al., 2008). Most of the microfluidic Coulter counters can only be used for cell counting and static cell sizing, do not support successive volume measurements for single cells, since they have only one, two or very limited numbers of electrode pairs (Wu, Y. et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2012; Wu, Y.F. et al., 2010).

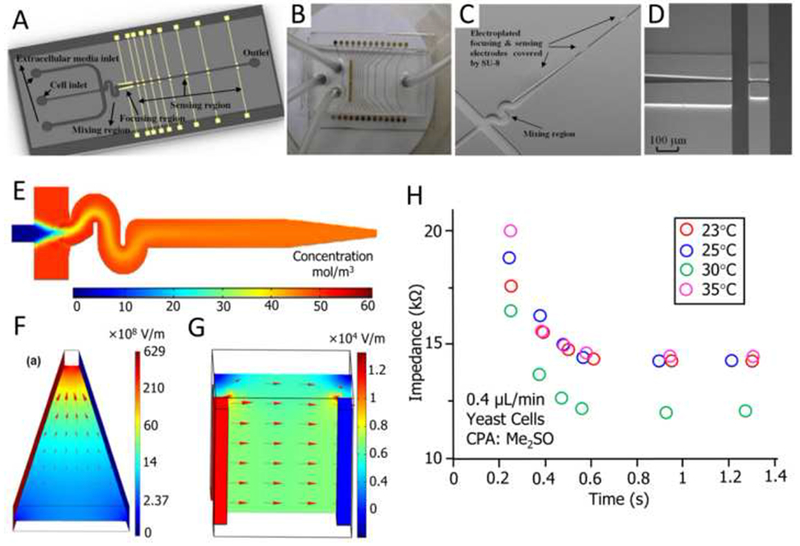

Wu et al. developed a novel MEMS Coulter counter that support continuously detecting and monitoring the dynamic cell impedance changes for single cells (Wu, Y. et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2012; Wu, Y.F. et al., 2010) (Figure 6). In their design, the mixing, focusing and sensing regions are integrated into a single microdevice (Figures 6A and B), which are constituted by a ‘S’ shaped microchannel (Figure 6C), a ramp down vertical electrode pair (Figure 6D), and multi-electrodes with vertical sidewalls (Figures 6A and D). Theoretical analysis indicates that sufficient passive mixing with high efficiency (Figure 6E), adequate flow focusing (Figure 6F), and measurement of transient impedance changes with significantly enhanced sensitivity (benefit from the uniform electrical field over the entire height of the microchannel produced by a vertical electrode pair, Figure 6G) are all achieved by this microfluidic Coulter counter (Wu, Y. et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2012; Wu, Y.F. et al., 2010). Then, it was successfully applied for the measurement of the impedance changes of yeast cells after mixing with dimethyl sulfoxide (Me2SO) at four different temperatures (Figure 6H). This Coulter counter has greatly enriched the scope of the microfluidic devices for characterization of cell membrane transport properties, it owns the unique features for rapidly measurement of the impedance changes of the cells without the dependence on cell shapes, while with high precision and low consumption of samples and reagents.

Figure 6. A MEMS-based Coulter counter for cell counting and sizing using multiple electrodes.

(A) Three-dimensional schematic of the MEMS Coulter counter. (B) A complete fabricated and packaged Coulter counter with PDMS cover. (C) SEM image of the microfluidic channel for mixing and sensing. (D) SEM image of gold electroplated focusing and detection electrodes. (E) Simulation of the mixing of two dyes. (F) Simulation of electric field and its gradient distribution in the focusing electrode pair. (G) Simulated electric field in a vertical electrode pair. (H) Measurement of the impedance changes of yeast cells after mixing with dimethylsulfoxide (Me2SO) at four different temperatures. Reproduced from (Wu, Y. et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2012) with permission.

4. Controllable addition and removal of CPAs

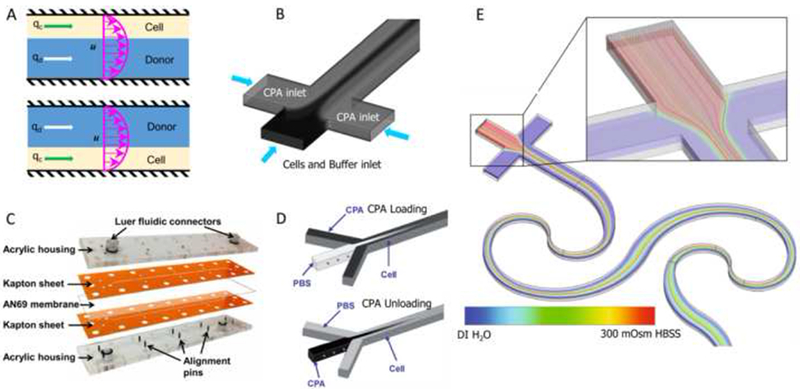

Optimization of CPA loading/unloading protocols based on precisely determined cell membrane transport properties, including water and CPA permeability and their activation energies, is a precondition for pre- and post-processing of cell suspensions prior to and after freeze-thaw cycles. Exploiting flow characteristics in microchannels, considerable efforts have focused on using microfluidics to accomplish CPA loading/unloading on a chip. Chandran and colleagues (Bala Chandran et al., 2012) investigated the influence of buoyancy-driven flow on mass transfer in a two-stream microfluidic channel, and successfully introduced the typical CPA (10% v/v DMSO) into a cell suspension (Jurkat cells) using this device (Figure 7A). Scherr and co-workers (Scherr et al., 2013) conducted a numerical study of flow field and the concentration distribution during CPA loading into cells in a three inlet T-junction microchannel, and found that each cell has a unique path in the flow field, and thus a distinctive extracellular concentration profile (Figure 7B). For practical use with more realistic and more complicated mixtures of cryoprotectants, they then simulated loading of cryoprotectant cocktails-on-a-chip (Scherr et al., 2014a, b). Data show that the chip provided both controlled loading of CPA to minimize osmotic shock and selective loading of a specific CPA from several to fulfill special requirements.

Figure 7. Microfluidics enabled CPA loading/unloading.

(A) Two-stream microfluidic device. (B) three-inlet T-junction microchannel. (C) membrane-based microfluidic device. (D) three-inlet Y-junction microchannel. (E) A sequential logarithmic microfluidic mixer for zebrafish sperm activation. Reproduced from (Bala Chandran et al., 2012; Lusianti and Higgins, 2014; Scherr et al., 2013; Song et al., 2009)(Scherr et al., 2015) with permission.

Lusianti and colleagues (Lusianti and Higgins, 2014) developed a microfluidic membrane device, consisting of two laser-patterned Kapton sheets, an AN69 hemodialysis membrane, and a clear acrylic housing, which could be used for continuous removal of glycerol from freeze-thawed erythrocytes (Figure 7C). Fleming et al. (Fleming et al., 2007) developed a diffusion-based model to investigate DMSO extraction in a fully developed channel containing a washing flow parallel to a DMSO-laden cell suspension. Theoretical predictions and preliminary experiments confirmed an applicable design. Song et al. (Song et al., 2009) designed and fabricated a microfluidic device with a three-input channel (100 μm × 100 μm × 1.5 m), and reported that the long channel offered continuous changes in CPA concentration along the length by diffusion (Figure 7D). The device allows control of loading and unloading of CPAs in the microchannel using diffusion and laminar flow. Although CPA loading/unloading of large sample volumes is challenging, microfluidic devices provide a feasible, robust, and easy-to-implement method for effectively controlling osmotic shock, and can be exploited for future uses.

Additionally, sperm cryopreservation is a critical part of assisted reproductive technology (ART) (Araki et al., 2015; Tomita et al., 2016; Zou et al., 2013), while most of the applications of microfluidics in sperm processing were focused on sorting or isolation of sperm from semen sample; few studies were found on CPA addition and removal (Cho et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2014; Li et al., 2016; Samuel et al., 2016; Sano et al., 2010; Schuster et al., 2003). Fortunately, both the designs for the staggered herringbone microfluidic mixer (Park et al., 2012) and the passive, planar micromixer based on logarithmic spirals (Scherr et al., 2015; Scherr et al., 2012) (Figure 7E), which are initially developed for sperm activation, can be potentially adopted for CPA processing, since where controllable extracellular mixing is supplied.

5. Cooling and warming: programmable freezing and vitrification

Cell-based measurement and diagnosis with microfluidic devices are increasingly being used with the implementation of freeze-thaw cycles on a chip offering potentially seamless cell preparation and use. Cryopreservation of limited cells such as oocytes, sperm (azoospermia; severe oligozoospermia), and spermatogonic stem cells remains a challenge for traditional methods but cooling and warming on a chip may address novel needs. Also, microfluidics can be used for microscale encapsulation of cells, which allows cell vitrification with low CPA concentration (Huang et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2013; Zhao, S.T. et al., 2014).

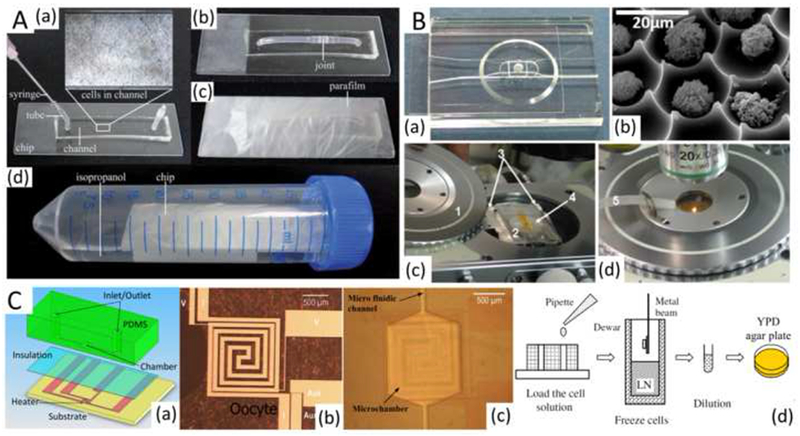

5.1. Controlled slow freezing and programmable freezing

Li et al. (Li et al., 2014) proposed a novel cryopreservation method for directly freezing and thawing mammalian cells. This was achieved on a PDMS-glass chip with a straight microchannel into which the cell suspension was first injected. The chip was then packed with parafilm or placed in a small Ziploc bag and put into a centrifuge tube filled with isopropyl alcohol, and maintained in a −80 °C cryogenic refrigerator for further use (Figure 8A). With this technique, several mammalian cells were successfully cryopreserved for several days/months, including cancer cells (SKBR3 and HepG2), endothelial cells (human umbilical vein endothelial cells), and fibroblasts (3T3 cells). By supporting direct freezing and thawing cells on chip, instead of thawing and culturing cells in flasks and transferring them into the micro channels, this approach offers the capacity for remarkable reduction in valuable cells, reagent and the preparation time consumption for on-chip cell-based experiments, and provides ready-to-use kits for on-chip cell-based experiments (Li et al., 2014).

Figure 8. Microfluidics for controllable freezing and thawing.

(A) On-chip direct freezing/thawing of mammalian cells. (B) Individual-cell-based microfluidic chip mounted onto a cryostage for programmed freezing/thawing of cells. (C) A microfabricated chip with an incubation microchamber, microfluidic channels, and microheaters for on-chip cell cryopreservation. Reproduced from (Afrimzon et al., 2010; Deutsch et al., 2010; Li et al., 2014; Li et al., 2010) with permission.

Toner’s group (Roach et al., 2009) creatively developed a microwell array for studying cryo-responses in an array of single cells, where thousands of individual cells are seeded in a high density grid of cell-sized microwells, as makes it possible for high-throughput tracking and imaging of the cells through manipulations as extreme as freezing or drying. Later, Deutsh et al. and Afrimzon et al. (Afrimzon et al., 2010; Deutsch et al., 2010) introduced an individual cell-based cryo-chip (i3C) with an array of picowells (Figure 8B), enabling individual cell cryopreservation, observation, and retrieval for the first time. Furthermore, i3C is compatible with commonly used, commercially available cryostage (MDBCS 600; Linkam Instruments, Tadworth, UK), which extends its application to include programmed freezing and thawing of cells on a chip.

Another microfluidic device, consisting of a PDMS microchamber with fluidic channels and a microheater/temperature sensor covered with an electrical insulation layer on top of the silicon substrate (Figure 8C), has been successfully used for two-step, temperature-controlled, on-chip cryopreservation of yeast cells (Li et al., 2010). Controlled freezing on the chip offers better survival (74% and 38% at holding temperatures of −25 °C and −40 °C, respectively) compared with direct freezing with liquid nitrogen vapor (27%). Likely a more accurate temperature sensor, such as the recently reported submicrometer and nano scale sensors (Huo et al., 2014), and feedback control on the microheaters, can improve cell survival (Li et al., 2010).

5.2. Ultra-rapid cooling and vitrification

As an important supplement to programmed freezing, microfluidics is widely tested and has been adopted for vitreous cryopreservation. With conventional vitrification, the greatest challenge is the addition/removal of high CPA concentrations that are toxic. Due to the fact that the ultra-rapid cooling is technically difficult to achieve, high CPA concentrations are routinely needed to decrease the critical cooling rates for vitrification, therefore, various microfluidics have been applied for addition/removal of high CPA concentrations (Bala Chandran et al., 2012; Fleming et al., 2007; Heo et al., 2011; Park et al., 2011; Pyne et al., 2014; Song et al., 2009). Exposure time and osmotic stress could be well controlled by slow cell shrinkage on a microfluidic platform, and current achievements with mammalian oocytes, zygotes, and embryos are inspiring (Lai et al., 2015a; Pyne et al., 2014).

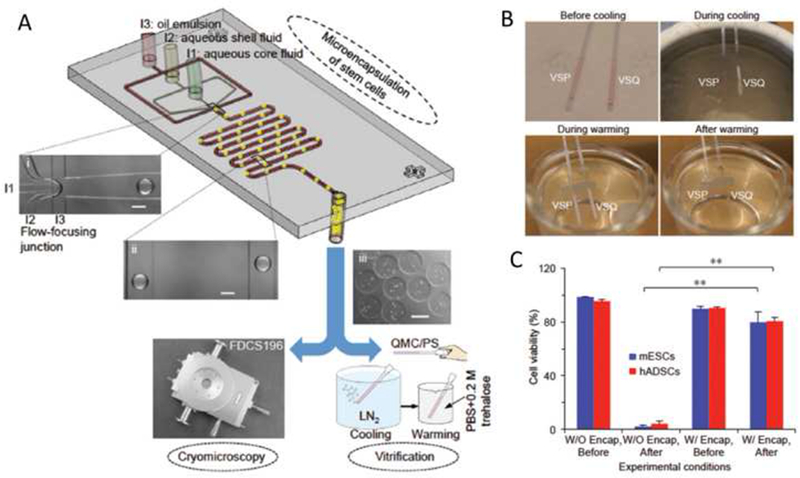

For ultra-rapid cooling and warming, microfluidics can assist with the major challenge to cell vitrification: devitrification and/or recrystallization during rewarming of vitrified cells (Fahy et al., 1984; Fahy and Wowk, 2015). Till now, only limited sample volumes (up to 2.5 μL) and/or high CPA concentrations (up to 8 M) allow vitrification (Huang et al., 2015). Most recently, a nonplanar microfluidic flow-focusing device was developed to encapsulate cells at a micrometer scale (Huang et al., 2015) (Figure 9(A)), and then cells encapsulated with alginate hydrogel could be loaded into plastic straws (PS) for vitrification with only 2 M of penetrating CPAs in up to 100 times greater sample volumes (up to 250 μL) (Figure 9B). Experiments with mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) and human adipose-derived stem cells (hADSCs) indicate that stress-sensitive stem cells can be vitrified with this approach with survival exceeding 80% (Figure 9C). Further studies indicates that devitrification could be effectively inhibited by alginate hydrogel microencapsulation and no significant IIF could occur in the encapsulated cells during warming, that’s the underlining mechanism for low-CPA cryopreservation by alginate hydrogel microencapsulation (Huang et al., 2015).

Figure 9. Microfluidics facilitate microencapsulation of cells for low-CPA vitreous cryopreservation (Huang et al., 2015).

(A) A nonplanar microfluidic flow-focusing device for microencapsulation of cells. (B) Vitrification of VSP but not VSQ during cooling with PS, and devitrification of the vitrified VSP during warming with the PS. (C) Viability of mESCs and hADSCs with (W/) or without (W/O) alginate hydrogel encapsulation (Enap) before and after vitrification in VSP. **: p<0.01. VSP: cell culture medium containing 2M PROH and 1.3M trehalose. VSQ: cell culture medium containing 1.5M PROH and 0.5M trehalose. PS: conventional plastic straw. mESCs: mouse embryonic stem cells. hADSCs: human adipose–derived stem cells.

Because cell suspensions can be confined to a microscale, at least in one dimension such as a thin liquid film, the surface-area-to-volume ratio can be greatly increased and accordingly heat transfer can be easily and significantly enhanced. Typically, if the cell suspension is dispersed into microscale droplets, and then the cells encapsulated in the CPA droplets with appropriate sizes are ejected directly into liquid nitrogen, vitrification at low cryoprotectant concentration is possible: e.g., i) 1.5 M propanediol and 0.5 M trehalose for AML-12 hepatocytes, NIH-3T3 fibroblasts, HL-1 cardiomyocytes, mouse embryonic stem cells, and RAJI cells, ii) 2.5 M glycerol for human red blood cells, and iii) 1.4 M ethylene glycol, 1.1 M dimethyl sulfoxide and 1 M sucrose for mice oocytes (Demirci and Montesano, 2007; Samot et al., 2011; Song et al., 2010; Zhang, X.H. et al., 2012). For all these cases using ultra-rapid cooling, CPA concentration involved is similar to that used in slow freezing protocols. Thus, compared with traditional freezing methods, ultra-rapid and uniform cooling is potentially available with a microfluidic platform. In cryopreservation, low-CPA or CPA-free vitrification is the ultimate objective and microfluidics platforms may permit this objective to be reached (Huang et al., 2015; Zou et al., 2013). So far, microfluidics for vitrification cryopreservation is still being explored.

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Significant advances in the application of microfluidics for cryopreservation of cells, while maintaining viability and biological functionality have been achieved, but the full potential remains unexplored. Addition and removal of CPAs at a secure level is routinely required, while as is especially a challenge for vitrification cryopreservation, since where high CPA concentrations are involved. Although multi-step CPA introduction and washing is currently used, manual manipulation makes these processes labor intensive, time consuming, costly, agent and cell consuming, and lacking quality controls. Microfluidics can provide efficient and reliable trials for combining CPA types, concentrations and exposure as well as optimizing CPA exchange protocols by controlling change rates, and minimal and maximal cell volume values. Similarly, cooling and warming on a chip is also an emerging milestone for cryopreservation by controlled or programmable freezing, since microfluidics offers cell-oriented temperature control with high precision. Furthermore, the high surface-area-to-volume ratio of cell suspension on a chip intrinsically enables rapid cooling and warming needed for vitrification. More importantly, this technique provides an urgently needed method for preserving very limited volumes of biological samples, as often occurs with assisted reproductive technologies and stem cell research (Araki et al., 2015; Cohen and Garrisi, 1997; Cohen et al., 1997; Montag et al., 1998; Rao et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016). Microfluidics can further be used to produce biological agents and cells in micro-scale volumes, enabling low-CPA droplet or encapsulation vitrification (Choi et al., 2015a; He et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2015; Risco et al., 2007; Tasoglu et al., 2013).

As an important development direction, microfluidics can also be used for all-in-one and ready-to-use experimental platforms for cell-based assays (Kondo et al., 2016). Interestingly, procedures including cell culture, CPA addition, freeze-thaw cycle, CPA removal, and subsequent cell viability evaluation, including cell diagnosis, cytotoxicity testing, and culture and investigation, could be integrated on a single chip which would replace multiple steps. This way, the cryopreservation and cell-based diagnostic chips could be potentially combined, allowing a powerful tool for both lab-on-chip technology and microchip-based biomedical science (Li et al., 2014).

Microfluidics is also an amazing technology for fertility preservation, including gamete and embryo cryopreservation (Heo et al., 2011; Pyne et al., 2014). Significant progress has been made in recent years for application of microfluidics in ART, e.g., sperm activation, sorting and isolation, oocyte processing, fertilization, and embryo culture (Cho et al., 2003; de Wagenaar et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2014; Li et al., 2016; Ohta et al., 2010; Samuel et al., 2016; Sano et al., 2010; Scherr et al., 2015; Schuster et al., 2003; Suh et al., 2003; Tsai et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2011b). As an important and indispensable part of fertility preservation, cryopreservation on-chip has also achieved considerable progress, e.g., on-chip CPA-free cryopreservation of small amounts of human spermatozoa was successfully accomplished (Zou et al., 2013). Single or a small number of human sperms have been successfully cryopreserved using microcapsules (Araki et al., 2015; Cohen and Garrisi, 1997; Cohen et al., 1997; Montag et al., 1998), and due to the fact that microfluidics is an well-established method for cell encapsulation (Huang et al., 2015; Koster et al., 2008; Zimmermann et al., 2007), we believe that cryopreservation of gamete and embryo on-chip is an emerging technology which will cause extensive attention.

Regarding the need for rapid screening of optimal cryopreservation protocols in ART, such as in situ sperm and oocyte preservation, a microfluidic device-based automatic system for cryopreservation is urgently needed. As mentioned above, most of the procedures involved in ART, including sperm activation, sorting and isolation, oocyte processing, fertilization, embryo culture, and gamete and embryo cryopreservation are now possible to be performed on-chip (Heo et al., 2011; Lai et al., 2015b; Pyne et al., 2014; Swain et al., 2013), thus the time is ripe to develop a micro-total-ART system for fertility preservation, with all these functions integrated on a chip.

In spite of the aforementioned advantages of microfluidics for cryopreservation, low production rate of cell encapsulation (by droplets, alginate hydrogel, or some other biocompatible materials) and very limited sample volume containing have become a major hindrance to their widespread applications at the laboratorial and clinical scale (Jeong et al., 2016). Fortunately, several reports have recently shown that one possible way to overcome this challenge is to parallelize a large number of microfluidic cell encapsulation units and networks of microchannels onto a single chip, or a chipset (Korczyk et al., 2015; Mulligan and Rothstein, 2012; Tendulkar et al., 2012). In this way, widespread utilization of the microfluidics for cryopreservation is entirely feasible.

Last but certainly not least, automation is also a very important aspect in the design and application of the cryopreservation chips. Automation of complex-step procedures for cryopreservation chips could eliminate run-to-run and operator-to-operator variability in the laboratory and in clinical applications, and promote process standardization by increasing consistency and reliability. Integration of microfluidics for cryopreservation with automation is promising, as it can lower manufacturing cost, reagent and sample consumption, decrease labor intensity, increase production rate, improve ease-to-use, offer high-throughput, and may promote point-of-care cryopreservation. On-chip cryopreservation is emerging technique that may fulfill novel needs for functionality and clinical applications. Highly integrated, automatic and standard platforms will optimize cryopreservation to support technologies in engineering and the life sciences.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by grants from the National Science Foundation of China (Nos. 51276179, 51476160, and 51528601).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Acker JP, 2007. Biopreservation of cells and engineered tissues, in: Lee K, Kaplan D (Eds.), Tissue Engineering II. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 157–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acker JP, 2008. Biopreservation and cellular therapies. ISCT Telegraft 15(2), 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Afrimzon E, Zurgil N, Shafran Y, Ehrhart F, Namer Y, Moshkov S, Sobolev M, Deutsch A, Howitz S, Greuner M, Thaele M, Meiser I, Zimmermann H, Deutsch M, 2010. The individual-cell-based cryo-chip for the cryopreservation, manipulation and observation of spatially identifiable cells. II: Functional activity of cryopreserved cells. Bmc Cell Biol 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agca Y, Mullen S, Liu J, Johnson-Ward J, Gould K, Chan A, Critser J, 2005. Osmotic tolerance and membrane permeability characteristics of rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) spermatozoa. Cryobiology 51(1), 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen ED, Weatherbee L, Spencer HH, Lindenauer SM, Permoad PA, 1975. Further Studies on Cryopreservation of Large Volumes of Red-Cells with Hydroxyethyl Starch. Cryobiology 12(6), 561–561. [Google Scholar]

- Araki Y, Yao T, Asayama Y, Matsuhisa A, Araki Y, 2015. Single human sperm cryopreservation method using hollow-core agarose capsules. Fertility and sterility 104(4), 1004–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bala Chandran R, Reinhart J, Lemke E, Hubel A, 2012. Influence of buoyancy-driven flow on mass transfer in a two-stream microfluidic channel: Introduction of cryoprotective agents into cell suspensions. Biomicrofluidics 6(4), 44110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benelli C, De Carlo A, Engelmann F, 2013. Recent advances in the cryopreservation of shoot-derived germplasm of economically important fruit trees of Actinidia, Diospyros, Malus, Olea, Prunus, Pyrus and Vitis. Biotechnology advances 31(2), 175–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson JD, Chicone CC, Critser JK, 2005a. Exact solutions of a two parameter flux model and cryobiological applications. Cryobiology 50(3), 308–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson JD, Chicone CC, Critser JK, 2011. A general model for the dynamics of cell volume, global stability, and optimal control. Journal of mathematical biology 63(2), 339–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson JD, Haidekker MA, Benson CMK, Critser JK, 2005b. Mercury free operation of the coulter counter multisizer II sampling stand. Cryobiology 51(3), 344–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson JD, Kearsley AJ, Higgins AZ, 2012. Mathematical optimization of procedures for cryoprotectant equilibration using a toxicity cost function. Cryobiology 64(3), 144–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HH, Purtteman JJP, Heimfeld S, Folch A, Gao D, 2007. Development of a microfluidic device for determination of cell osmotic behavior and membrane transport properties. Cryobiology 55(3), 200–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HH, Shen H, Heimfeld S, Tran KK, Reems J, Folch A, Gao DY, 2008. A microfluidic study of mouse dendritic cell membrane transport properties of water and cryoprotectants. Int J Heat Mass Tran 51(23–24), 5687–5694. [Google Scholar]

- Cho BS, Schuster TG, Zhu XY, Chang D, Smith GD, Takayama S, 2003. Passively driven integrated microfluidic system for separation of motile sperm. Anal Chem 75(7), 1671–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JK, Huang HS, He XM, 2015a. Improved low-CPA vitrification of mouse oocytes using quartz microcapillary. Cryobiology 70(3), 269–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JK, Yue T, Huang H, Zhao G, Zhang M, He X, 2015b. The crucial role of zona pellucida in cryopreservation of oocytes by vitrification. Cryobiology 71(2), 350–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SG, Haubert K, Beebe DJ, Ferguson CE, Wheeler MB, 2005. Reduction of polyspermic penetration using biomimetic microfluidic technology during in vitro fertilization. Lab Chip 5(11), 1229–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Garrisi GJ, 1997. Micromanipulation of gametes and embryos: Cryopreservation of a single human spermatozoon within an isolated zona pellucida. Human reproduction update 3(5), 453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Garrisi GJ, Congedo-Ferrara TA, Kieck KA, Schimmel TW, Scott RT, 1997. Cryopreservation of single human spermatozoa. Human reproduction 12(5), 994–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro RM, Stirling S, Fahy GM, de Magalhaes JP, 2015. Insights on cryoprotectant toxicity from gene expression profiling of endothelial cells exposed to ethylene glycol. Cryobiology 71(3), 405–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson AF, Benson JD, Higgins AZ, 2014. Mathematically optimized cryoprotectant equilibration procedures for cryopreservation of human oocytes. Theor Biol Med Model 11, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson AF, Glasscock C, McClanahan DR, Benson JD, Higgins AZ, 2015. Toxicity Minimized Cryoprotectant Addition and Removal Procedures for Adherent Endothelial Cells. Plos One 10(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wagenaar B, Dekker S, de Boer HL, Bomer JG, Olthuis W, van den Berg A, Segerink LI, 2016. Towards microfluidic sperm refinement: impedance-based analysis and sorting of sperm cells. Lab Chip 16(8), 1514–1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirci U, Montesano G, 2007. Cell encapsulating droplet vitrification. Lab Chip 7(11), 1428–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch M, Afrimzon E, Namer Y, Shafran Y, Sobolev M, Zurgil N, Deutsch A, Howitz S, Greuner M, Thaele M, Zimmermann H, Meiser I, Ehrhart F, 2010. The individual-cell-based cryo-chip for the cryopreservation, manipulation and observation of spatially identifiable cells. I: Methodology. Bmc Cell Biol 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebertz SL, McGann LE, 2002. Osmotic parameters of cells from a bioengineered human corneal equivalent and consequences for cryopreservation. Cryobiology 45(2), 109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebertz SL, McGann LE, 2004. Cryoprotectant permeability parameters for cells used in a bioengineered human corneal equivalent and applications for cryopreservation. Cryobiology 49(2), 169–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmoazzen HY, Elliott JAW, McGann LE, 2002. The effect of temperature on membrane hydraulic conductivity. Cryobiology 45(1), 68–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy GM, 1981. Prospects for Vitrification of Whole Organs. Cryobiology 18(6), 617–617. [Google Scholar]

- Fahy GM, 1986a. The relevance of cryoprotectant “toxicity” to cryobiology. Cryobiology 23(1), 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy GM, 1986b. Vitrification: a new approach to organ cryopreservation. Progress in clinical and biological research 224, 305–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy GM, 1987. Vitrification of Multicellular Systems and Whole Organs. Cryobiology 24(6), 580–580. [Google Scholar]

- Fahy GM, 1994. Organ perfusion equipment for the introduction and removal of cryoprotectants. Biomedical instrumentation & technology / Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation 28(2), 87–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy GM, 2010. Cryoprotectant toxicity neutralization. Cryobiology 60(3), S45–S53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy GM, Karow AM Jr., 1977. Ultrastructure-function correlative studies for cardiac cryopreservation. V. Absence of a correlation between electrolyte toxicity and cryoinjury in the slowly frozen, cryoprotected rat heart. Cryobiology 14(4), 418–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy GM, Kittrell JL, Severns M, 1985. A Fully Automated-System for Treating Organs with Cryoprotective Agents. Cryobiology 22(6), 607–608. [Google Scholar]

- Fahy GM, Lilley TH, Linsdell H, Douglas MS, Meryman HT, 1990. Cryoprotectant Toxicity and Cryoprotectant Toxicity Reduction - in Search of Molecular Mechanisms. Cryobiology 27(3), 247–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy GM, MacFarlane DR, Angell CA, Meryman HT, 1984. Vitrification as an approach to cryopreservation. Cryobiology 21(4), 407–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy GM, Wowk B, 2015. Principles of cryopreservation by vitrification, in: Wolkers WF, Oldenhof H (Eds.), Cryopreservation and Freeze-Drying Protocols. Springer; New York, pp. 21–82. [Google Scholar]

- Fahy GM, Wowk B, Pagotan R, Chang A, Phan J, Thomson B, Phan L, 2009. Physical and biological aspects of renal vitrification. Organogenesis 5(3), 167–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy GM, Wowk B, Wu J, Paynter S, 2004a. Improved vitrification solutions based on the predictability of vitrification solution toxicity. Cryobiology 48(1), 22–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy GM, Wowk B, Wu J, Paynter S, 2004b. Improved vitrification solutions based on the predictability of vitrification solution toxicity (vol 48, pg 22, 2004). Cryobiology 48(3), 365–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy GM, Wowk B, Wu J, Phan J, Rasch C, Chang A, Zendejas E, 2004c. Cryopreservation of organs by vitrification: perspectives and recent advances. Cryobiology 48(2), 157–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng C, Yin Z, Ma Y, Zhang Z, Chen L, Wang B, Li B, Huang Y, Wang Q, 2011. Cryopreservation of sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas) and its pathogen eradication by cryotherapy. Biotechnology advances 29(1), 84–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming KK, Longmire EK, Hubel A, 2007. Numerical characterization of diffusion-based extraction in cell-laden flow through a microfluidic channel. Journal of biomechanical engineering 129(5), 703–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry AK, Higgins AZ, 2012. Measurement of Cryoprotectant Permeability in Adherent Endothelial Cells and Applications to Cryopreservation. Cell Mol Bioeng 5(3), 287–298. [Google Scholar]

- Gao D, Crister JK, 2000. Mechanisms of cryoinjury in living cells. ILAR J 41(4), 187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao DY, Benson CT, Liu C, McGrath JJ, Critser ES, Critser JK, 1996. Development of a novel microperfusion chamber for determination of cell membrane transport properties. Biophys J 71(1), 443–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawad S, Schild L, Renaud P, 2001. Micromachined impedance spectroscopy flow cytometer for cell analysis and particle sizing. Lab Chip 1(1), 76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazar AI, Mullen SF, Liu J, Benson JD, Critser JK, Squires EL, Graham JK, 2009. Osmotic tolerance limits and membrane permeability characteristics of stallion spermatozoa treated with cholesterol. Cryobiology 59(2), 201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C, Zhang QF, Ma R, Xie L, Qiu TA, Wang L, Mitchelson K, Wang JD, Huang GL, Qiao J, Cheng J, 2010. Integration of single oocyte trapping, in vitro fertilization and embryo culture in a microwell-structured microfluidic device. Lab Chip 10(21), 2848–2854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, 2011. Thermostability of biological systems: fundamentals, challenges, and quantification. The open biomedical engineering journal 5, 47–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He XM, Park EYH, Fowler A, Yarmush ML, Toner M, 2008. Vitrification by ultra-fast cooling at a low concentration of cryoprotectants in a quartz micro-capillary: A study using murine embryonic stem cells. Cryobiology 56(3), 223–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo YS, Lee HJ, Hassell BA, Irimia D, Toth TL, Elmoazzen H, Toner M, 2011. Controlled loading of cryoprotectants (CPAs) to oocyte with linear and complex CPA profiles on a microfluidic platform. Lab Chip 11(20), 3530–3537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HS, Choi JK, Rao W, Zhao ST, Agarwal P, Zhao G, He XM, 2015. Alginate Hydrogel Microencapsulation Inhibits Devitrification and Enables Large-Volume Low-CPA Cell Vitrification. Advanced Functional Materials 25(44), 6839–6850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HY, Wu TL, Huang HR, Li CJ, Fu HT, Soong YK, Lee MY, Yao DJ, 2014. Isolation of motile spermatozoa with a microfluidic chip having a surface-modified microchannel. Journal of laboratory automation 19(1), 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo X, Liu H, Liang Y, Fu M, Sun W, Chen Q, Xu S, 2014. A nano-stripe based sensor for temperature measurement at the submicrometer and nano scales. Small 10(19), 3869–3875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihmig FR, Shirley SG, Kirschman RK, Zimmermann H, 2013. Frozen Cells and Bits. Ieee Pulse 4(5), 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasim IH, Agca Y, Almasri M, Benson JD, 2015. A microfluidic coulter counter for dynamic sizing and cell volume control. Cryobiology 71(3), 538. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong HH, Issadore D, Lee D, 2016. Recent developments in scale-up of microfluidic emulsion generation via parallelization. Korean J Chem Eng 33(6), 1757–1766. [Google Scholar]

- Jin B, Mazur P, 2015. High survival of mouse oocytes/embryos after vitrification without permeating cryoprotectants followed by ultra-rapid warming with an IR laser pulse. Sci Rep 5, 9271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julca I, Alaminos M, Gonzalez-Lopez J, Manzanera M, 2012. Xeroprotectants for the stabilization of biomaterials. Biotechnology advances 30(6), 1641–1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson JOM, Cravalho EG, Toner M, 1994. A Model of Diffusion-Limited Ice Growth Inside Biological Cells During Freezing. J Appl Phys 75(9), 4442–4445. [Google Scholar]

- Khirabadi BS, Ali S, Fahy G, 1988. Rabbit Kidney Auto-Transplantation - Attempts to Develop a Model for Evaluation of Organ Preservation Techniques. Cryobiology 25(6), 512–512. [Google Scholar]

- Kilbride P, Lamb S, Milne S, Gibbons S, Erro E, Bundy J, Selden C, Fuller B, Morris J, 2016. Spatial considerations during cryopreservation of a large volume sample. Cryobiology 73(1), 47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinhans FW, Seki S, Mazur P, 2010. Simple, inexpensive attainment and measurement of very high cooling and warming rates. Cryobiology 61(2), 231–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M, Evans AGR, Brunnschweiler A, 1999. Design and fabrication of a micromachined Coulter counter. J Micromech Microeng 9(2), 159–161. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo E, Wada K, Hosokawa K, Maeda M, 2016. Cryopreservation of adhered mammalian cells on a microfluidic device: Toward ready-to-use cell-based experimental platforms. Biotechnology and bioengineering 113(1), 237–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korczyk PM, Dolega ME, Jakiela S, Jankowski P, Makulska S, Garstecki P, 2015. Scaling up the Throughput of Synthesis and Extraction in Droplet Microfluidic Reactors. J Flow Chem 5(2), 110–118. [Google Scholar]

- Koster S, Angile FE, Duan H, Agresti JJ, Wintner A, Schmitz C, Rowat AC, Merten CA, Pisignano D, Griffiths AD, Weitz DA, 2008. Drop-based microfluidic devices for encapsulation of single cells. Lab Chip 8(7), 1110–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuleshova L, Hutmacher D, 2008. Chapter 13 - Cryobiology A2 - Blitterswijk Clemens van, in: Thomsen P, Lindahl A, Hubbell J, Williams DF, Cancedda R, Bruijn J.D.d., Sohier J (Eds.), Tissue Eng. Academic Press, Burlington, pp. 363–401. [Google Scholar]

- Lai D, Ding J, Smith GW, Smith GD, Takayama S, 2015a. Slow and steady cell shrinkage reduces osmotic stress in bovine and murine oocyte and zygote vitrification. Human reproduction 30(1), 37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai D, Takayama S, Smith GD, 2015b. Recent microfluidic devices for studying gamete and embryo biomechanics. Journal of biomechanics 48(9), 1671–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibo SP, Mazur P, Chu EHY, 1970. 2 Factors Responsible for Freezing Injury in Hamster Tissue Culture Cells. Cryobiology 6(6), 580–&. [Google Scholar]

- Li JC, Zhu SB, He XJ, Sun R, He QY, Gan Y, Liu SJ, Funahashi H, Li YB, 2016. Application of a microfluidic sperm sorter to in vitro production of dairy cattle sex-sorted embryos. Theriogenology 85(7), 1211–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Lv XQ, Guo H, Shi XT, Liu J, 2014. On-chip direct freezing and thawing of mammalian cells. RSC advances 4, 34443–34447. [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Liu W, Lin LW, 2010. On-Chip Cryopreservation of Living Cells. Journal of laboratory automation 15(2), 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Benson CT, Gao D, Haag BW, McGann LE, Critser JK, 1995. Water permeability and its activation energy for individual hamster pancreatic islet cells. Cryobiology 32(5), 493–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Zieger MAJ, Lakey JRT, Woods EJ, Critser JK, 1997. The determination of membrane permeability coefficients of canine pancreatic islet cells and their application to islet cryopreservation. Cryobiology 35(1), 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Zhao G, Shu ZQ, Wang T, Zhu KX, Gao DY, 2015. High-precision approach based on microfluidic perfusion chamber for quantitative analysis of biophysical properties of cell membrane. Int J Heat Mass Tran 86, 869–879. [Google Scholar]

- Lusianti RE, Benson JD, Acker JP, Higgins AZ, 2013. Rapid removal of glycerol from frozen-thawed red blood cells. Biotechnol Progr 29(3), 609–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusianti RE, Higgins AZ, 2014. Continuous removal of glycerol from frozen-thawed red blood cells in a microfluidic membrane device. Biomicrofluidics 8(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luyet BJ, Rapatz GL, 1971. Search for Concentrations of Cryoprotectants Innocuous in Heart Perfusion. Cryobiology 8(4), 378–&. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu S-R, Chen W-J, Hsieh W-H, 2014. Measuring transport properties of cell membranes by a PDMS microfluidic device with controllability over changing rate of extracellular solution. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 197, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mazur P, 1970. Cryobiology - Freezing of Biological Systems. Science 168(3934), 939–&. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur P, 1984. Freezing of living cells: mechanisms and implications. Am J Physiol 247(3), C125–C142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur P, 2004. Principles of Cryobiology, in: Barry JF, Nick L, Erica EB (Eds.), Life in the Frozen State. CRC PRESS, Boca Raton London New York Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Mazur P, Leibo SP, Chu EH, 1972. A two-factor hypothesis of freezing injury. Evidence from Chinese hamster tissue-culture cells. Exp Cell Res 71(2), 345–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JJ, 1985. A microscope diffusion chamber for the determination of the equilibrium and non-equilibrium osmotic response of individual cells. Journal of microscopy 139(Pt 3), 249–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]